Abstract

The gut microbiota is comprised of a vast variety of microbes that colonize the gastrointestinal tract and exert crucial roles for the host health. These microorganisms, partially via their breakdown of dietary components, are able to modulate immune response, mood, and behavior, establishing a chemical dialogue in the microbiota–gut–brain interphase. Changes in the gut microbiota composition and functionality are associated with multiple diseases, in which altered levels of gut-associated neuropeptides are also detected. Gut neuropeptides are strong neuroimmune modulators; they mediate the communication between the gut microbiota and the host (including gut–brain axis) and have also recently been found to exert antimicrobial properties. This highlights the importance of understanding the interplay between gut neuropeptides and microbiota and their implications on host health. Here, we will discuss how gut neuropeptides help to maintain a balanced microbiota and we will point at the missing gaps that need to be further investigated in order to elucidate whether these molecules are related to neuropsychiatric disorders, which are often associated with gut dysbiosis and altered gut neuropeptide levels.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The gut microbiota comprises a complex community of metabolically active microorganisms that have a strong influence on a wide range of physiological processes, such as immune and nervous system development, food metabolism, cell growth and differentiation, or mood and behavior (Dinan and Cryan 2017; El Aidy et al. 2013; El Aidy et al. 2016; Erny et al. 2015; Rowland et al. 2018; Taylor and Holscher 2018). Though the composition of the gut microbiota is unique for each individual and therefore it is not possible to determine what defines a “healthy microbiota,” it seems clear that alterations in the composition of the gut microbiota, known as dysbiosis, are associated with multiple diseases, including neuropsychiatric disorders and inflammatory gastrointestinal diseases (Koopman and El Aidy 2017; Pusceddu et al. 2018). Thus, it is of great significance to investigate the mechanisms involved in the interplay between the microbiota and the host.

One of the ways by which the gut bacteria establish their intimate relationship with their host is through the production of biologically active molecules. Bacteria produce these molecules by breaking down dietary compounds that reach the intestine and/or the indigenously produced compounds that are expelled from the intestine (Dodd et al. 2017; Strandwitz 2018; Zhang and Davies 2016). Products of bacterial breakdown range from immunomodulatory to antimicrobial and neuroactive compounds that not only have a local action on the host but can also reach the blood stream to have an impact on distant parts of the body (Lyte and Cryan 2014).

Neuropeptides are now in the spotlight as one of the potential mediators of the exchange of information between gut bacteria and other tissues and organs. Their role as modulators of neuronal and immune functions is well known and reveals a strikingly complex network through which neuropeptides exert multiple functions. Although the term “neuropeptide” is commonly used in the context of the central nervous system (CNS), the enteric nervous system (ENS) is another major source of production of these peptides. Therefore, in this article, we will use the term “gut neuropeptides” to specifically refer to neuropeptides which are produced in the ENS, as opposed to other gut peptides which are also produced in the intestinal epithelium. This term also reinforces the idea that gut neuropeptides are able to exert an extraintestinal action by signaling to distant organs, such as the brain. Interestingly, several gut neuropeptides also have antimicrobial activity; for instance, neuropeptide Y (NPY) and substance P (SP), which have been shown to inhibit the growth of Escherichia coli (Hansen et al. 2006). However, the antimicrobial activity of gut neuropeptides has not been studied in detail yet. Considering that gut antimicrobial neuropeptides are produced not only in the CNS but also in the ENS and their respective receptors are widely expressed along the gastrointestinal tract (GIT), it is important to unravel the function of these peptides in the context of gut microbiota homeostasis, which is key for a healthy state of the host. Finally, gut neuropeptides might also be key regulators of the so-called microbiota–gut–brain axis; for example, through their receptors expressed on the vagus nerve, the main communication route between the gut and the CNS (Holzer and Farzi 2014). In this review article, we will describe the different types of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) that are present in the gut and their mode of action. Thereafter, we will focus on gut neuropeptides and will address their direct and indirect function in maintaining homeostasis.

Antimicrobial peptides in the gastrointestinal tract

The GIT is a major entry point of microbes, and so, the organ has developed a complex defense mechanism to protect the host from diseases, as part of the innate immune system. One of the components of this defense barrier is the AMPs. In the GIT, AMPs are produced not only by the intestinal epithelium but also by the gut microbiota in the lumen (Table 1). As presented in Table 1, human defense peptides have a rather broad spectrum of action, whereas their bacterial counterparts display a much narrower spectrum. This is due to a very specific mode of action of bacterial AMPs where the antimicrobial action takes place upon high-affinity binding to receptors in the cell envelope (Martinez et al. 2016).

Antimicrobial peptides produced by the gut microbiota

Gut bacteria represent a major source of AMPs production in the GIT. These bacteria synthesize the so-called bacteriocins. Similar to AMPs produced by human cells, bacteriocins are small, cationic peptides that can easily interact with bacterial membranes. So far, 177 bacteriocins have been identified and sequenced; 88% of them are produced by Gram-positive bacteria, whereas the remaining 12% are produced by Gram-negative bacteria and Archaea. It is also remarkable that most of the reported Gram-positive bacteriocins producers belong to the group of lactic acid bacteria, which carry out fermentation of sugar into lactic acid (http://bactibase.hammamilab.org/statistics.php). However, it cannot be concluded that lactic acid bacteria are the only bacteriocin producers; instead, given the interest that they pose for the food industry, it is likely that most of the research has been focused on this group of bacteria and accordingly more bacteriocins have been reported to be produced by lactic acid bacteria.

Bacteriocins are classified into many different subgroups due to the heterogenicity of this group of molecules. Bacteriocins that are produced by Gram-negative bacteria are referred to as microcins, small peptides, or colicins, which are larger proteins. Microcins are subsequently divided into class I (< 5 kDa, containing post-translational modifications) and class II (5–10 kDa, without post-translational modifications) (Hassan et al. 2012). Despite their structural diversity, microcins share an interesting mechanism of action that has been named the “Trojan Horse” strategy. Some microcins such as MccJ25 and MccE492 mimic the structure of essential bacterial molecules and take advantage of the natural receptors for these ligands, which allow them to enter and kill the target bacteria. On the other hand, MccC7 and MccC59 are secreted as harmless molecules and further transformed into toxic derivatives once they enter the susceptible bacteria (Duquesne et al. 2007). An interesting example of how microcins are relevant for the host was shown recently using a mouse model of intestinal inflammation. In the study of Sassone-Corsi et al., probiotic E. coli Nissle 1917, which produces microcins, was able to restrict the expansion of other competing Enterobacteriaceae during inflammation, including pathogenic E. coli and Salmonella enterica. Also, therapeutic administration of E. coli Nissle was sufficient to effectively displace enteric pathogens from their niche due to their production of microcins (Sassone-Corsi et al. 2016). The second subgroup of Gram-negative bacteriocins, colicins, are larger peptides produced by some strains of E. coli and other related Enterobacteriaceae. They are active against E. coli and closely related bacteria such as Salmonella (Braun et al. 1994). Similarly to microcins, colicins are quite a diverse group that includes up to 30 types of proteins which slightly differ in lethal activity and mode of action (Smarda and Smajs 1998). The mechanism by which colicins kill bacteria has been extensively studied and consists of three main steps. Initially, colicins bind to the outer membrane proteins of the target cell through the receptor binding domain. Then, the translocation domain located in the N-terminus of the protein allows colicins to enter the target cell: depending on which protein complex they interact with, colicins are subdivided into Tol-dependent or Ton-dependent colicins. These periplasmic protein complexes allow colicins to translocate and reach the inner membrane where the killing activity takes place by different mechanisms: pore formation, DNAse activity, or inhibition of protein synthesis (Cascales et al. 2007). Interestingly, a very recent study analyzed clinical isolates of E. coli from the intestinal mucosa of patients suffering from inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and found a higher frequency of bacteriocinogeny when compared to healthy subjects. The study found that IBD E. coli strains had a higher prevalence of virulence determinants when compared to healthy controls, suggesting that IBD E. coli strains closely resemble their pathogenic counterparts. One of these determinants was group B colicins, which are actually encoded in plasmids containing additional virulence genes. This association between IBD and group B colicins could therefore reflect additional virulence determinants present in the colicin plasmids highly prevalent in IBD (Micenková et al. 2018). The use of recombinant colicins directed to specific pathogenic E. coli strains present in IBD has been proposed as a therapeutic method for IBDs (Kotłowski 2016). Thus, genetically modified E. coli Nissle 1917 could be used as a vehicle to introduce specific colicins in the GIT that would reinforce the antimicrobial action that this strain exerts through the production of microcins (Kotłowski 2016). However, it is important to note that this hypothesis has not been yet tested in the laboratory, so in vitro and in vivo experiments are needed to confirm the potential of colicins as therapeutic agents in intestinal inflammation.

Bacteriocins produced by Gram-positive bacteria are divided into lantibiotics and non-lantibiotics. Lantibiotics constitute the Gram-positive counterpart of microcins; they are small peptides, below 5 kDa, and contain unusual post-translationally modified residues such as lanthionine and 3-methly-lathionine (Perez et al. 2014). The first lantibiotic ever discovered was Nisin A (Rogers and Whittier 1928), and a lot of studies are still being done on how to genetically modify this peptide to create derivatives improving its antimicrobial properties (Field et al. 2012; Li et al. 2018). Lantibiotics are quite unique molecules; they present unusual thioether-containing amino acid residues that form ring structures within the peptides (Jack and Jung 2000), which is probably linked to their complex mechanism of action. The mode of action of these antimicrobials was for a long time thought to be restricted to the pore formation mechanism of the prototypic lantibiotic nisin (Garcerá et al. 1993). However, upon structural derivatization, new insights reveal a complex set of modes of action that are combined to eventually disrupt bacterial growth. For instance, nisin takes the pore formation process one step further, increasing the specificity and stability of the pore through the interaction with lipid II. Lipid II is a molecule that is anchored to cell membranes and acts as a precursor in the synthesis of peptidoglycan by translocating across the membrane the building blocks required for its synthesis (van Heijenoort 2007). By binding to lipid II, nisin is able to greatly improve the pore-forming efficiency (Breukink et al. 1999) and this mechanism has also been described in other lantibiotics, such as the two-peptide lantibiotic lacticin 3147 (Wiedemann et al. 2006) and subtilin (Parisot et al. 2008). Interestingly, the interaction with lipid II has another effect that also increases the potency of these molecules as antibiotics. As lipid II is a precursor in the synthesis of peptidoglycan, the interaction with nisin sequesters lipid II from its normal function and results in the inhibition of cell membrane biosynthesis, which creates the dual effect of this lantibiotic (Wiedemann et al. 2001).

In a similar way to microcins, Gram-positive bacteriocins also have great therapeutic potential. For example, enterococcal bacteriocin 21 might constitute an effective approach to decolonize antibiotic-resistant enterococci from the gut. In a recent study, commensal Enterococcus faecalis delivering bacteriocin 21 was used to specifically disrupt the growth of multidrug-resistant enterococci during infection in the mammalian GIT. Thus, a particular niche from the gut microbiota was inhibited without altering the rest of the microbial population, which poses a useful strategy to treat infections caused by antibiotic resistant strains that might otherwise be very challenging to cure (Kommineni et al. 2015).

Antimicrobial peptides produced by the intestinal mucosa

The intestinal epithelium provides the first line of defense against microorganisms that reach the gut lumen and can be pathogenic for the host. Intestinal epithelial cells are mainly enterocytes, but they also comprise enteric neurons, enteroendocrine cells, tuft cells, and secretory cells, which include goblet and Paneth cells. Goblet cells produce mucin and Paneth cells secrete AMPs, creating a physical and biochemical barrier that ensures the proper segregation between host and microorganisms, helping to avoid infections (Allaire et al. 2018). It must be noted, however, that Paneth and goblet cells are not the only source of host-derived AMPs. These epithelial secretory cells are aided by classic immune cells located in the lamina propria, which include lymphocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells for the production of AMPs (Charles et al. 2001).

So far, five different AMPs and proteins have been found to be produced by Paneth cells: defensins, cathelicidins, lysozyme C, phospholipase A2, and REGIIIα/β/γ. Lysozyme C, a glycoside hydrolase that cleaves specific residues of peptidoglycan causing lysis of the bacterial membrane, was firstly found to be expressed in Paneth cells (Mason and Taylor 1975). Phospholipase A2 was also found to be synthesized in Paneth cells (Nevalainen et al. 1995) and described as a bactericidal agent against E. coli and Listeria monocytogenes. Furthermore, Paneth cells produce REGIIIα, a C-type lectin also known as HIP/PAP (hepatocarcinoma–intestine–pancreas/pancreatic-associated protein), which is produced in enteroendocrine cells as well (Lasserre et al. 1999). REGIIIα, as many other antimicrobial peptides, is able to kill bacteria by formation of a permeabilizing transmembrane pore, although this mechanism is inhibited by lipopolysaccharides (LPS), which is why this peptide is only effective against Gram positive-bacteria (Mukherjee et al. 2013). Additionally, REGIII peptides play an important role during the initial establishment of the gut microbiota in germ-free mice. Indeed, REGIIIγ and REGIIIβ expressions have been shown to peak during the process of gut bacterial colonization in both the small intestine and the colon of mouse, coinciding with induced expression of innate immune molecules phospholipase A2 (Pla2g2a) and resistin-like beta (Retnlβ) in the colon (El Aidy et al. 2012). Later on, the expression of REGIII peptides in the colon returned to basal levels detected in germ free animals. This suggests that REGIII peptides exert an antimicrobial function in the small intestine, while Pla2g2a and Retnlβ exert this antimicrobial function in the colon (El Aidy et al. 2012).

The major AMP components in the intestinal mucosa are defensins. So far, ten defensins have been identified and divided in two groups according to structural features: human α-defensins (HDs) and human β-defensins (HBDs). Defensins are small, cationic peptides with a rather broad spectrum of antimicrobial activity in vitro and they exert their function by creating micropores in the bacterial membranes that cause the leak of the cell’s content, loss of structure, and eventual cell death (Cobo and Chadee 2013; Cunliffe 2003). They are synthesized as propeptides and are subsequently cleaved by proteases to form the mature, active forms of the peptides (Valore & Valore and Ganz 1992). HDs are produced by Paneth cells and are therefore in charge of protection in the small intestine, whereas HBDs play the same role in the colon, where they are secreted by epithelial cells. Additionally, HDs are produced by immune cells including monocytes, macrophages, T and B cells, which also produce HBDs together with dendritic cells (Dutta and Das 2016).

The other family of AMPs produced in the GIT by the host is cathelicidins. Among cathelicidins, only LL-37 is expressed in humans. Cathelicidins and defensins share some common features; LL-37 is also synthesized as a propeptide, which is later cleaved by a protease to release the mature peptide with antimicrobial activity (Zaiou and Gallo 2002). Furthermore, the mode of action of LL-37 is also based on bacterial membrane disruption by pore formation (Xhindoli et al. 2016). However, in contrast to defensins, which are only expressed in the small intestine, LL-37 expression in this region of the intestinal tract is rather low, while it is highly abundant in the colon (Schauber et al. 2003), where it is secreted by colonocytes (Hase et al. 2002).

Antimicrobial gut neuropeptides

There is increasing evidence that gut neuropeptides are one of the axes of communication between the gut microbiota and the host (El Aidy et al. 2016) and they might also be playing a role as antimicrobial agents. Gut neuropeptides are structurally similar to regular antimicrobial peptides; they are small (< 10 kDa), cationic, and amphipathic molecules and also share similarities with other AMPs in their mode of action. Even though their antimicrobial properties have not yet been studied in detail, there are multiple indications that gut neuropeptides such as NPY, SP, α-melanocyte stimulating hormone (α-MSH), vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), and adrenomedullin (AM) might be having an important role in the regulation of the gut microbiota composition.

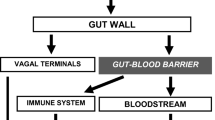

Gut neuropeptides emerge not only from enteric neurons in response to different stimuli (Fig. 1) but also from immune cells and enteroendocrine cells (Yoo and Mazmanian 2017). The ENS extends from the myenteric plexus of the intestine and reaches the intestinal epithelium, being able to sense different stimuli across several layer of the intestine and to regulate multiple intestinal functions (Furness 2012). For instance, sensory neurons reaching the epithelium can detect stressful stimuli such as pathogenic bacteria and secrete SP, which subsequently induces cytokine secretion from immune cells (Fig. 1). Gut neuropeptides, including gut antimicrobial neuropeptides, are therefore part of an extremely complex network between the nervous and immune systems where they are playing a key modulatory role.

Direct and indirect effects of gut neuropeptides in the GIT. Upon sensing of stressful stimuli, enteric neurons release gut neuropeptides that induce a response in innate and adaptive immune cells, which also secrete these peptides, resulting in a strong response to bacterial imbalance. Additionally, if gut neuropeptides cross the epithelial barrier, they could exert a direct antimicrobial activity in the intestinal lumen by different killing mechanisms

NPY is a 36 amino acid peptide produced by enteric neurons, and it regulates a wide variety of physiological processes in the gut such as gut motility, inflammation, cytokine secretion, and epithelial permeability (Chandrasekharan et al. 2013). In the gut, Y1, Y2, Y4, and Y5 receptors (which belong to the family of G protein coupled receptors, GPCRs) present in enteric neurons and enterocytes mediate the gastrointestinal motility control of NPY (Holzer et al. 2012). Furthermore, sufficient evidence supports the role of NPY as a key modulator of the neuroimmune crosstalk (Bedoui et al. 2003). Interestingly, NPY has been reported as an antimicrobial agent in vitro against Cryptococcus neoformans, Candida albicans, and Arthroderma simii, with a minimal inhibitory concentration of 7 μM (Vouldoukis et al. 1996). SP is a much smaller peptide of only 11 amino acids, highly conserved and expressed in enteric nerves, enteric sensory neurons, and enteric immune cells. As NPY, it has multiple roles in gut physiology such as mediating inflammation, nociception, muscle contraction, and gut motility, as well as being another modulator of the neuroimmune communication, via neurokinin receptors NK1R and NK2R, which are also GPCRs (Koon and Pothoulakis 2006). SP has also been shown to display antimicrobial activity in vitro against Staphylococcus aureus, E. coli, E. faecalis, Proteus vulgaris, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and C. albicans. The antimicrobial activity of SP and NPY against E. coli, E. faecalis, P. aeruginosa, and C. albicans was confirmed in a different study, which also showed activity of both gut neuropeptides against Streptococcus mutans and Lactobacillus acidophilus (El Karim et al. 2008). However, two more recent studies failed to show inhibition of growth of S. aureus and another Pseudomonas strain (P. fluorescens) upon exposure to SP (Mijouin et al. 2013; N’Diaye et al. 2016). Furthermore, in another study, both SP and NPY only showed antimicrobial activity against E. coli, failing to have an effect on S. aureus and C. albicans (Hansen et al. 2006). Resistance of S. aureus to SP and NPY was also shown by Karim et al., so it seems like this bacterium is not affected by any of these gut neuropeptides. The discrepancies in the results obtained with respect to certain strains might be due to the use of laboratory strains versus fresh isolates or to the use of different methods, but given their structural features, their production in abundance in the gut and the physiological roles of these two peptides, their antimicrobial capacity needs to be further investigated.

Another important gut neuropeptide is α-MSH, a 13 amino acid peptide that emerges from the post-translational processing of POMC (proopiomelanocortin). As other gut neuropeptides, it is an important neuroimmune modulator being a potent antiinflammatory molecule, which allows it to regulate intestinal permeability (Váradi et al. 2017). α-MSH also exerts its function through another member of the GPCR family of receptors; melanocortin receptors (MCRs) bind α-MSH triggering different signaling pathways that regulate a variety of functions. In the gut, MC1R and MC3R induction by α-MSH modulates its antiinflammatory response through cyclic adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate (cAMP) signaling (Singh and Mukhopadhyay 2014). α-MSH antimicrobial activity was first shown against E. coli, C. albicans, and S. aureus (Cutuli et al. 2000), which was later extended to Cryptococcus neoformans (Masman et al. 2006) and C. vaginitis (Catania et al. 2005).VIP is another gut neuropeptide which has been shown to display promising antimicrobial activity, at least against some pathogens (El Karim et al. 2008). VIP is a 28 amino acid peptide that is also present in the GIT, where it regulates different function through the VPAC2 receptors, which belong to GPCR family too. Apart from being an important immune regulator, VIP regulates vasodilatation in the gut, as well as motility (Mario Delgado and Ganea 2013). Regarding its antimicrobial activity, VIP was shown to be effective in killing S. mutans, E. coli, P. aeruginosa, and C. albicans in vitro. Additionally, VIP was also able to kill the pathogen Trypanosoma brucei in another in vitro study (M. Delgado et al. 2009). However, not many follow-up studies on the antimicrobial properties of VIP are available. Instead, a few studies with synthetic analogues of the peptide with improved stability have shown enhanced antimicrobial activity of VIP. Indeed, modified VIP peptides were able to kill S. mutans, Micrococcus luteus, and pathogenic E. faecalis, while the native peptide was ineffective against these bacteria against S. aureus and E. coli compared to the native form of the peptide (Campos-Salinas et al. 2014). Using also analogues of VIP, Xu et al. were able to demonstrate antimicrobial activity against S. aureus and E. coli that was increased when compared to the natural form of the peptide (Xu et al. 2017). Finally, CGRP is another gut neuropeptide that has been investigated as an antimicrobial peptide. In its mature form, it is composed of 37 amino acids and has two splicing variants; α-CGRP and β-CGRP. α-CGRP is predominantly expressed not only in the CNS but also in the peripheral nervous system, whereas β-CGRP is mostly found in the ENS. This peptide causes vasodilation in the GIT and has a protective role against ischemia (Ma 2016). Regarding its antimicrobial activity, CGRP is able to affect the growth of E. coli, C. albicans and P. aeruginosa (El Karim et al. 2008), therefore having quite a restricted spectrum of action, as compared with the other gut neuropeptides discussed before. Within the CGRP family of peptides, it is also important to mention AM. This 52 amino acid peptide is generated by post-translational enzymatic processing of preproadrenomedullin, which also results in the formation of its gene-related peptide proadrenomedullin N-terminal peptide (PAMP) (Bełtowski and Jamroz 2004). AM shares structural and functional similarities with CGRP, such as the presence of an internal molecular ring and a central helical region for receptor binding, and both peptides exert their functions through the calcitonin receptor-like receptor (CRLR) (Hay and Walker 2017; Pérez-Castells et al. 2012). AM and PAMP are found across the entire GIT, being specially abundant in neuroendocrine cells, and they regulate growth of the intestinal epithelium, water, and ion transport in the colon, intestinal motility, and vasodilatation (Martínez-Herrero and Martínez 2016). Antimicrobial properties have also been described for both peptides; antimicrobial activity of AM was initially shown against a range of bacteria known to be members of the microbiota of different mucosal surfaces, including intestinal mucosa. AM was able to inhibit the growth of Bacteroides fragilis and E. coli (Allaker et al. 1999), and this was extended in a later study to PAMP, which was actually shown to be even more potent than AM against E. coli (Marutsuka et al. 2001).

As shown in Table 1, the antimicrobial activity of gut neuropeptides has mainly been tested against pathogenic bacteria. Although of high relevance, it is still necessary to study antimicrobial activity of gut neuropeptides on commensal bacteria. Not only inflammation can be caused by colonization of pathogens, but also certain strains of commensal bacteria, such as E. coli, can trigger the production of cytokines and induce an inflammatory state in the gut that can translate to the brain. (Kittana et al. 2018). Therefore, the role of these peptides as antimicrobial agents against commensal strains should be further explored in order to understand their potential impact in the host health.

Modes of action of antimicrobial gut neuropeptides

As mentioned before, the common structural features of host defense peptides and antimicrobial gut neuropeptides allow the latter to exert their function through the same mechanisms of action on the target microorganisms. These include membrane disruption, interference with cell division, and metabolism or disruption of ATP synthesis among others. Furthermore, gut neuropeptides have an additional capacity of interacting with the neuro- and immune systems, which ultimately causes the release of other molecules with antimicrobial activity. This combined action raises a great potential for gut neuropeptides to be used with therapeutic purposes in order to treat diseases associated with microbiota alterations, especially in light of the increasing resistance to conventional antibiotics that is putting at risk the use of these drugs.

Direct antimicrobial effects of gut neuropeptides

The mechanism of action of antimicrobial peptides has been studied in depth mostly in host defense peptides, but the structural similarities of gut neuropeptides, which are also small, cationic molecules, allow them to exert their function in a similar way. The predominant antimicrobial mode of action of gut neuropeptides consists of binding and disruption of the bacterial cell wall. Indeed, membrane disruptive mechanisms have been shown to drive the action of NPY (Thomas et al. 2005), α-MSH (Madhuri et al. 2009), and AM (Allaker et al. 2006), all of which contain a rich combination of positively charge amino acids and hydrophobic residues in their C-terminal fragment. However, non-disruptive mechanisms also exist and will be discussed later on.

Membrane-disruptive peptides usually form α-helical structures with accumulation of positively charged residues towards the C-terminal side of the peptide (Powers and Hancock 2003). This allows the initial step to approach their target, which occurs through electrostatic interactions of such residues with the anionic LPS that coat the outer bacterial membrane. By displacement of Mg2+ and Ca2+ ions that are usually interacting with LPS, antimicrobial peptides create local disturbances in the membrane, allowing their translocation and making the inner cytoplasmic membrane accessible (Hancock and Chapple 1999). The next step consists of the reorientation of the peptide to interact with the inner membrane. Different mechanistic models have been proposed for the interaction of these peptides with inner bacterial membranes, and although, it is not yet clear which is correct, they all lead to the disruption and depolarization of the membrane, which rapidly causes cell death (Sato and Feix 2006). It is easy to speculate that there might not be one unique model to explain the mode of action of these peptides, but instead, they might all be correct depending on the physicochemical properties of each antimicrobial peptide.

Interestingly, another rather non-traditional mode of action has been described to take place in the trypanolytic activity of gut neuropeptides AM and VIP. Trypanosomiasis is known to cause intestinal damage in humans, as an inflammatory state is induced upon the invasion of this parasite with increased cytokine levels and intestinal permeability (Ben-Rashed et al. 2003). Studying the antimicrobial activity of different gut neuropeptides on T. brucei, an unusual antimicrobial mechanism was found in which the peptides are subjected to endocytosis through the flagellar pocket of this microorganism. Next, trafficking of the peptides through the endosomal network allows them to reach the lysosomes, where they disrupt endosome–lysosome vesicles. Disruption of these membranes causes the release of the gut neuropeptides to the cytosol, together with glycolytic enzymes, which leads to a metabolic failure and finally to cell death (Delgado et al. 2009).

Finally, AM has also been shown to have a distinct, unusual mechanism of action against S. aureus. Staphylococci division occurs though the inwards growth of the peripheral cell wall and formation of a transverse cross wall, known as septum. Then, the newly synthesized peptidoglycan undergoes localized hydrolysis that results in complete cell separation (Giesbrecht et al. 1998). In S. aureus, AM has been shown to disrupt the formation of the septum (Allaker et al. 2006), which is known to lead to cell death in other organisms.

Even though these results are promising and present gut neuropeptides as potential modulators of gut microbiota homeostasis by direct antimicrobial activity, some questions need to be addressed before they can be implemented as therapeutic agents. The studies discussed above are in vitro studies, and it is not yet clear whether these gut neuropeptides reach the gut microbiota in sufficient amounts. For them to be effective in direct killing of bacteria, gut neuropeptides should be able to reach the gut lumen or areas in close proximity to the intestinal epithelium, where they may exert a very important role in gut microbiota homeostasis. Another concern for their potential therapeutic implementation is that, as mentioned before, most of the studies so far have tested antimicrobial activity against pathogenic bacteria, which leaves commensal bacteria unexplored. It would therefore be crucial to unravel whether these peptides can keep infections under control without altering the composition of commensal bacteria residing in the GIT. In light of the growing resistance of pathogens to the currently used broad-spectrum antibiotics, exploring the therapeutic possibilities of gut neuropeptides is extremely significant; these peptides could be active against resistant strains and their seemingly restricted spectrum of action would not influence other untargeted bacteria, reducing the possibilities of developing resistance.

Indirect antimicrobial effects of gut neuropeptides

Besides their antimicrobial action on microbes, gut neuropeptides have much more sophisticated roles and probably the more important antiinfective functions of these molecules rely on their neuroimmune modulatory properties. Such features have allowed the host to develop a complex and intrinsic network of defense mechanisms to protect itself from microbial invasion. Gut neuropeptides respond to gut microbiota alterations by mediating the so called neurogenic inflammation (Houser and Tansey 2017). At the same time, neuroimmune modulation by gut neuropeptides translates to changes in the ENS, which can eventually reach the brain and impact mood and behavior. Thus, inflammation in the GIT results in changes in ENS, such as increased number of enteric neurons, altered levels of gut neuropeptides and changes in the motor circuits of the intestine (Margolis and Gershon 2016).

Nociceptors, which are specialized peripheral sensory neurons, respond to damaging stimuli in the GIT such as infection by releasing gut neuropeptides. SP, CGRP, AM, and NPY are released from these neurons and mediate neurogenic inflammation as a defense mechanism for the host. This way, during the effector phase of inflammation, sensory neurons produce neuropeptides that promote proliferation and migration of immune cells, guiding them to the specific site of damage (Chiu et al. 2012). NPY, SP, and CGRP are able to stimulate the release of proinflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and arachidonic acid from immune and non-immune cells, while VIP, α-MSH, and AM seem to have the opposite effect. Altogether, they mediate neurogenic inflammation (Fig. 1) (Mitchell and King 2010; Souza-Moreira et al. 2011). A detailed description of the action of neuropeptides on the immune system is provided in the review articles by Souza-Moreira et al. and Mitchell et al. Interestingly, one of the properties that make gut neuropeptides such potent mediators of the inflammatory response is their often synergetic activity with other molecules, which allows them to orchestrate an intense and efficient response. For instance, SP and CGRP have been shown to act jointly on peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC). This synergetic effect is in line with the additive effects that these peptides are known to have in other physiological processes involved in the inflammatory response; vasodilatation, vascular permeability, and hyperalgesia (Cuesta et al. 2002). SP has been shown to enhance the response of macrophages and monocytes by being able to strongly increase the release of cytokines and chemokines from these cells in response to LPS (Sipka et al. 2010). Another example of this coordinated action with other molecules is VIP, which is able to facilitate the bactericidal activity of human cathelicidin LL-37; when used in combination, VIP and LL-37 can keep their antimicrobial activity even at physiological concentrations of NaCl, at least against E. coli and P. aeruginosa (Ohta et al. 2011).

The complex picture of gut neuropeptide modulation of the immune response through their capacity to regulate innate and adaptive immune response via different receptors gives rise to a great variety of modes of action. For example, activation of neutrophil receptor Y5 by NPY potentiates a respiratory burst resulting in an increase of reactive oxygen species (ROS), one of the critical functions of neutrophils. Conversely, when NPY binds to Y1 and Y2 receptors, phagocytosis of E. coli is inhibited. Furthermore, the effect of this gut neuropeptide on neutrophils is also concentration-dependent; at low doses, NPY promotes phagocytosis, whereas at higher doses phagocytosis is inhibited and the respiratory burst is potentiated to eliminate the pathogen (Bedoui et al. 2008). On the other hand, a recent study using a SP agonist showed that stimulation of NK1R of dendritic cells promotes the maturation of these cells together with decreased secretion of IL-10 (Janelsins et al. 2013). Moreover, in line with its antiinflammatory effect described before, α-MSH drives the maturation of macrophages by interaction with MC1R receptors in these cells. Interestingly, this process has been specifically shown to kill C. albicans in a rat vaginitis model, again through cAMP signaling (Ji et al. 2013). CGRP is also able to regulate cells of the innate immune system. For instance, binding of the peptide to CRLR of macrophages induces IL-6 and TNF-α (Fernandez et al. 2001).

Regarding the interaction of gut neuropeptides with adaptive immune cells, SP has been reported to induce maturation of human memory CD4+ T cells into Th17 cells upon induction of IL-1β production in monocytes, an effect that occurs upon induction of NK1R in these cells (Cunin et al. 2011). α-MSH is also able to upregulate cytokine IL-10 in dendritic cells via MC1R, leading to the induction of regulatory T cells and eventual inhibition of effector T cells which points to an immunosuppressive phenotype (Auriemma et al. 2012). Another example is the ability of NPY to induce chemotaxis, adhesion to epithelial cells, and transepithelial migration of dendritic cells through Y1 receptor activation (Buttari et al. 2014).

In summary, gut neuropeptides allow the host to have a strong response to bacterial infections; damaging stimuli are sensed by sensory neurons, which in turn secrete these peptides that can directly act on microbes and at the same time induce inflammation through the interaction with immune cells in the intestinal mucosa. However, this complicated response has its implications on the GIT as it involves neuropeptide-mediated gastrointestinal inflammation on the ENS. An inflammatory state of the bowel induces severe changes in the ENS that result in gastrointestinal dysfunction. It has been shown that inflammation causes multiple changes in the intrinsic circuitry of the ENS, such as neuronal hyperexcitability, increased synaptic facilitation, and decreased inhibitory neuromuscular transmission (Krauter et al. 2007; Linden et al. 2004; Strong et al. 2010). This profound neuronal alteration ultimately leads to major, long-lasting disruption of the intestinal motor activity. Interestingly, bowel dysfunction is observed not only at the site of inflammation but also in non-inflamed regions of the gut, which might be explained by the long lasting alteration of enteric neuronal circuits. Altered motility and secretion can be found at distant, non-inflamed regions of the GIT, as shown in an experimental model of colitis in guinea pigs (Hons et al. 2009). In this study, non-cholinergic secretion was found to be decreased in the ileum where no inflammation was observed, and this change was associated with a decrease in excitatory synaptic transmission in secretomotor neurons. In contrast, ileal cholinergic neurons were more excitable, while action potentials in primary afferent neurons were broader than in a normal, non-inflamed state (Hons et al. 2009). Although the mechanism behind the distant effect of inflammation on non-affected regions of the gut is not yet understood, it seems clear that altered enteric neuronal function caused by neuropeptide-mediated inflammation can have effects in other regions of the GIT and this might be explained by a neuronal-mediated spread of the inflammation, resulting in profound and long lasting changes in the ENS across the whole bowel.

Conclusion

The gut microbiota is emerging lately as a key regulator of host health and disease. However, the mechanisms employed by these microbes to communicate with distant organs such as the brain are only beginning to be understood and antimicrobial gut neuropeptides are likely be involved in this process. Gut neuropeptides have the capacity to regulate gut microbiota homeostasis through both direct antimicrobial effects and neurogenic inflammation and therefore should be considered as potential therapeutic targets for diseases where this function is affected. Gut neuropeptides do seem to have a rather narrow spectrum as antimicrobial agents compared to defense peptides produced by Paneth cells. However, they should not be underestimated as potential alternatives to classic antibiotics, given their potent effects as neuroimmune modulators.

An important reason to further investigate the role of gut neuropeptides on intestinal homeostasis, possibility via an effect on gut microbiota composition, has to do with the fact that several neuropsychiatric disorders, which are associated with dysbiosis in the gut and intestinal inflammation, have also been described to be associated with altered levels of (gut) neuropeptides, though it is not yet clear whether disrupted levels of these neuropeptides are also detected in the GIT. For example, Autism spectrum disorder (ASD), which is characterized by a wide range of symptoms, including immune dysregulation, gut microbiota dysbiosis, and gastrointestinal dysfunction (Vuong and Hsiao 2018), has been linked with increased circulating levels of CGRP (Nelson et al. 2001). Major depressive disorder (MDD) seems to also be associated with increased levels of SP, which are restored after antidepressant treatment (Bondy et al. 2003; Lieb et al. 2004), together with altered levels of NPY (Morales-Medina et al. 2010). Another example is Parkinson’s disease (PD), a neurodegenerative disorder that presents gastrointestinal dysfunction and dysbiosis as comorbidities (Poirier et al. 2016; Sun and Shen 2018). Although more clinical trials are required to obtain consistent results, SP, NPY, and CGRP levels also seem to be altered in PD patients (Svenningsson et al. 2017; Thornton and Vink 2008). Finally, it is worth mentioning that a direct influence of gut microbiota on eating disorders has also been shown in the last years. Increased levels of bacterial induced α-MSH autoantibodies have been reported in patients with anorexia nervosa, bulimia, and binge eating disorder. The same study found that induction of α-MSH autoantibodies in mice was able to influence food intake, anxiety, and melanocortin signaling (Tennoune et al. 2014).

Taken together, there is sufficient data from both animal and human models that point to a key role of gut microbiota in neuropsychiatric disorders, which might be mediated in part by gut neuropeptides and their direct and indirect functions on the gut microbiota itself and the brain. However, more insights into the mechanisms are needed before any solid conclusion can be made. For example, there is no evidence regarding whether the elevated levels of these neuropeptides have an origin in the gut or how altered levels of circulating neuropeptides correlate with the progressing of intestinal inflammation in these disorders. Given the strong association of intestinal microbial dysbiosis with many neuropsychiatric or neurodegenerative disorders, it is worth addressing these questions which could potentially reveal gut neuropeptides as promising therapeutic agents in these pathological conditions.

References

Allaire JM, Crowley SM, Law HT, Chang S.-Y., Ko H.-J., & Vallance BA (2018) The intestinal epithelium: central coordinator of mucosal immunity https://doi.org/10.1016/j.it.2018.04.002

Allaker RP, Grosvenor PW, McAnerney DC, Sheehan BE, Srikanta BH, Pell K, Kapas S (2006) Mechanisms of adrenomedullin antimicrobial action. Peptides 27(4):661–666. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.peptides.2005.09.003

Allaker RP, Zihni C, Kapas S (1999) An investigation into the antimicrobial effects of adrenomedullin on members of the skin, oral, respiratory tract and gut microflora. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 23(4):289–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0928-8244(98)00148-5

Augustyniak D, Nowak J, Lundy FT (2012) Direct and indirect antimicrobial activities of neuropeptides and their therapeutic potential. Curr Protein Pept Sci 13(8):723–738. https://doi.org/10.2174/138920312804871139

Auriemma M, Brzoska T, Klenner L, Kupas V, Goerge T, Voskort M, Zhao Z, Sparwasser T, Luger TA, Loser K (2012) α-MSH-stimulated tolerogenic dendritic cells induce functional regulatory T cells and ameliorate ongoing skin inflammation. J Investig Dermatol 132(7):1814–1824. https://doi.org/10.1038/jid.2012.59

Bedoui S, Kawamura N, Straub RH, Pabst R, Yamamura T, von Hörsten S (2003) Relevance of neuropeptide Y for the neuroimmune crosstalk. J Neuroimmunol 134(1–2):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-5728(02)00424-1

Bedoui S, Kromer A, Gebhardt T, Jacobs R, Raber K, Dimitrijevic M, Heine J, von Hörsten S (2008) Neuropeptide Y receptor-specifically modulates human neutrophil function. J Neuroimmunol 195(1–2):88–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneuroim.2008.01.012

Bełtowski J, Jamroz A (2004) Adrenomedullin— what do we know 10 years since its discovery? Pol J Pharmacol 56(1):5–27

Ben-Rashed M, Ingram GA, Pentreath VW (2003) Mast cells, histamine and the pathogenesis of intestinal damage in experimental Trypanosoma brucei brucei infections. Ann Trop Med Parasitol 97(8):803–809. https://doi.org/10.1179/000349803225002444

Bondy B, Baghai TC, Minov C, Schüle C, Schwarz MJ, Zwanzger P, et al. (2003) Substance P serum levels are increased in major depression: preliminary results. Retrieved from https://ac.els-cdn.com/S0006322302015445/1-s2.0-S0006322302015445-main.pdf?_tid=4024d1e2-6169-4127-98af-2c2722541ae1&acdnat=1550500946_803dd6d99b2963865c4add8dad0d2f19

Braun V, Pilsl H, Gross P (1994) Colicins: structures, modes of action, transfer through membranes, and evolution. Arch Microbiol 161(3):199–206

Breukink E, Wiedemann I, van Kraaij C, Kuipers OP, Sahl H-G, de Kruijff B (1999) Use of the cell wall precursor lipid II by a pore-forming peptide antibiotic. Science 286(5448):2361–2364. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.286.5448.2361

Buttari B, Profumo E, Domenici G, Tagliani A, Ippoliti F, Bonini S, Businaro R, Elenkov I, Riganò R (2014) Neuropeptide y induces potent migration of human immature dendritic cells and promotes a Th2 polarization. FASEB J 28(7):3038–3049. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.13-243485

Campos-Salinas J, Cavazzuti A, O’valle F, Forte-Lago I, Caro M, Beverley SM et al (2014) Therapeutic efficacy of stable analogues of vasoactive intestinal peptide against pathogens. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M114.560573

Cascales E, Buchanan SK, Duche D, Kleanthous C, Lloubes R, Postle K, Riley M, Slatin S, Cavard D (2007) Colicin biology. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 71(1):158–229. https://doi.org/10.1160/TH10-02-0101

Catania A, Grieco P, Randazzo A, Novellino E, Gatti S, Rossi C et al (2005) Three-dimensional structure of the alpha-MSH-derived candidacidal peptide [Ac-CKPV]2. J Pept Res 66(1):19–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-3011.2005.00265.x

Chandrasekharan B, Nezami BG, Srinivasan S (2013) Emerging neuropeptide targets in inflammation: NPY and VIP. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 304(11):G949–G957. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpgi.00493.2012

Charles A Janeway J, Travers P, Walport M, & Shlomchik MJ (2001) The mucosal immune system. In Immunobiology: the immune system in health and disease (5th Edition). Garland Science. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK27169/

Chiu IM, von Hehn CA, Woolf CJ (2012) Neurogenic inflammation—the peripheral nervous system’s role in host defense and immunopathology. Nat Neurosci 15(8):1063–1067. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.3144.Neurogenic

Cobo E, Chadee K (2013) Antimicrobial human β-defensins in the colon and their role in infectious and non-infectious diseases. Pathogens 2(1):177–192. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens2010177

Cuesta MC, Quintero L, Pons H, Suarez-Roca H (2002) Substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide increase IL-1β, IL-6 and TNFα secretion from human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Neurochem Int 40(4):301–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0197-0186(01)00094-8

Cunin P, Caillon A, Corvaisier M, Garo E, Scotet M, Blanchard S, Delneste Y, Jeannin P (2011) The tachykinins substance P and hemokinin-1 favor the generation of human memory Th17 cells by inducing IL-1 , IL-23, and TNF-like 1A expression by monocytes. J Immunol 186(7):4175–4182. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.1002535

Cunliffe RN (2003) α-Defensins in the gastrointestinal tract. Mol Immunol 40(7):463–467. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0161-5890(03)00157-3

Cutuli M, Cristiani S, Lipton JM, Catania A (2000) Antimicrobial effects of α-MSH peptides. J Leukoc Biol 67(2):233–239. https://doi.org/10.1002/jlb.67.2.233

Dawson DMJ (2007) Lantibiotics as antimicrobial agents. Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Patents 17(4):365–369. https://doi.org/10.1517/13543776.17.4.365

Delgado M, Anderson P, Garcia-Salcedo JA, Caro M, Gonzalez-Rey E (2009) Neuropeptides kill African trypanosomes by targeting intracellular compartments and inducing autophagic-like cell death. Cell Death Differ 16(3):406–416. https://doi.org/10.1038/cdd.2008.161

Delgado M, Ganea D (2013) Vasoactive intestinal peptide: a neuropeptide with pleiotropic immune functions. Amino Acids 45(1):25–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00726-011-1184-8

Dinan TG, Cryan JF (2017) Microbes immunity and behavior: psychoneuroimmunology meets the microbiome. Neuropsychopharmacology 42(1):178–192. https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2016.103

Dodd D, Spitzer MH, Van Treuren W, Merrill BD, Hryckowian AJ, Higginbottom SK et al (2017) A gut bacterial pathway metabolizes aromatic amino acids into nine circulating metabolites. Nature 551(7682):648–652. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature24661

Duquesne S, Petit V, Peduzzi J, Rebuffat S (2007) Structural and functional diversity of microcins, gene-encoded antibacterial peptides from enterobacteria. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol 13(4):200–209. https://doi.org/10.1159/000104748

Dutta P, Das S (2016) Mammalian antimicrobial peptides: promising therapeutic targets against infection and chronic inflammation. Curr Top Med Chem 16(1):99–129. https://doi.org/10.2174/1568026615666150703121819

El Aidy S, Derrien M, Merrifield CA, Levenez F, Doré J, Boekschoten MV et al (2013) Gut bacteria-host metabolic interplay during conventionalisation of the mouse germfree colon. ISME J 7(4):743–755. https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2012.142

El Aidy S, Stilling R, Dinan TG, Cryan JF (2016) Microbiome to brain: unravelling the multidirectional axes of communication. Adv Exp Med Biol 874:301–336. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-20215-0_15

El Aidy S, Van Baarlen P, Derrien M, Lindenbergh-Kortleve DJ, Hooiveld G, Levenez F et al (2012) Temporal and spatial interplay of microbiota and intestinal mucosa drive establishment of immune homeostasis in conventionalized mice. Mucosal Immunol 5(5):567–579. https://doi.org/10.1038/mi.2012.32

El Karim IA, Linden GJ, Orr DF, Lundy FT (2008) Antimicrobial activity of neuropeptides against a range of micro-organisms from skin, oral, respiratory and gastrointestinal tract sites. J Neuroimmunol 200(1–2):11–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneuroim.2008.05.014

Erny D, de Angelis A, Jaitin D, Wieghofer P, Staszewski O, David E et al (2015) Host microbiota constantly control maturation and function of microglia in the CNS. Nat Neurosci 18(7):965–977. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.4030

Fernandez S, Knopf MA, Bjork SK, McGillis JP (2001) Bone marrow-derived macrophages express functional CGRP receptors and respond to CGRP by increasing transcription of c-fos and IL-6 mRNA. Cell Immunol 209(2):140–148. https://doi.org/10.1006/cimm.2001.1795

Field D, Begley M, O’Connor PM, Daly KM, Hugenholtz F, Cotter PD, Hill C, Ross RP (2012) Bioengineered Nisin a derivatives with enhanced activity against both gram positive and gram negative pathogens. PLoS One 7(10). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0046884

Furness JB (2012) The enteric nervous system and neurogastroenterology. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 9, 286. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1038/nrgastro.2012.32

Garcerá MJG, Elferink MGL, Driessen AJM, Konings WN (1993) In vitro pore-forming activity of the lantibiotic nisin: role of protonmotive force and lipid composition. Eur J Biochem 212(2):417–422. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb17677.x

Giesbrecht P, Kersten T, Maidhof H, & Wecke J (1998) Staphylococcal cell wall: morphogenesis and fatal variations in the presence of penicillin. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews

Hancock REW, Chapple DS (1999) Peptide antibiotics. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 43(6):1317–1323. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(97)80051-7

Hansen CJ, Burnell KK, Brogden KA (2006) Antimicrobial activity of substance P and neuropeptide Y against laboratory strains of bacteria and oral microorganisms. J Neuroimmunol 177(1–2):215–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JNEUROIM.2006.05.011

Hase K, Eckmann L, Leopard JD, Varki N, Kagnoff MF (2002) Cell differentiation is a key determinant of cathelicidin LL-37/human cationic antimicrobial protein 18 expression by human colon epithelium. Society 70(2):953–963. https://doi.org/10.1128/IAI.70.2.953

Hassan M, Kjos M, Nes IF, Diep DB, Lotfipour F (2012) Natural antimicrobial peptides from bacteria: characteristics and potential applications to fight against antibiotic resistance. J Appl Microbiol 113(4):723–736. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2672.2012.05338.x

Hay DL, Walker CS (2017) CGRP and its receptors. Headache 57(4):625–636. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.13064

Holzer P, Farzi A (2014) Neuropeptides and the microbiota-gut-brain axis. Adv Exp Med Biol 817:3–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-0897-4_1

Holzer P, Reichmann F, Farzi A (2012) Neuropeptide Y, peptide YY and pancreatic polypeptide in the gut-brain axis. Neuropeptides 46(6):261–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.npep.2012.08.005

Hons IM, Burda JE, Grider JR, Mawe GM, Sharkey KA (2009) Alterations to enteric neural signaling underlie secretory abnormalities of the ileum in experimental colitis in the guinea pig. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 296(4):G717–G726. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpgi.90472.2008

Houser MC, Tansey MG (2017) The gut-brain axis: is intestinal inflammation a silent driver of Parkinson’s disease pathogenesis? Npj Parkinson’s Disease 3(1):3. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41531-016-0002-0

Jack RW, Jung G (2000) Lantibiotics and microcins: polypeptides with unusual chemical diversity. Curr Opin Chem Biol 4(3):310–317. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1367-5931(00)00094-6

Janelsins BM, Sumpter TL, Tkacheva OA, Rojas-Canales DM, Erdos G, Mathers AR, Shufesky WJ, Storkus WJ, Falo LD, Morelli AE, Larregina AT (2013) Neurokinin-1 receptor agonists bias therapeutic dendritic cells to induce type-1 immunity by licensing host dendritic cells to produce IL-12. Blood 121(15):2923–2934. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2012-07-446054

Ji H.-X., Zou Y.-L., Duan J.-J., Jia Z.-R., Li X.-J., Wang Z., et al. (2013) The synthetic Melanocortin (CKPV) 2 exerts anti-fungal and anti-inflammatory effects against Candida albicans vaginitis via inducing macrophage M 2 polarization. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0056004

Kittana H, Gomes-Neto JC, Heck K, Geis AL, Segura Muñoz RR, Cody LA, Schmaltz RJ, Bindels LB, Sinha R, Hostetter JM, Benson AK, Ramer-Tait AE (2018) Commensal Escherichia coli strains can promote intestinal inflammation via differential Interleukin-6 production. Front Immunol 9:2318. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2018.02318

Kommineni S, Bretl DJ, Lam V, Chakraborty R, Hayward M, Simpson P, Cao Y, Bousounis P, Kristich CJ, Salzman NH (2015) Bacteriocin production augments niche competition by enterococci in the mammalian gastrointestinal tract. Nature 526(7575):719–722. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature15524

Koon HW, Pothoulakis C (2006) Immunomodulatory properties of substance P: the gastrointestinal system as a model. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1088(1):23–40. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1366.024

Koopman M, El Aidy S (2017) Depressed gut? The microbiota-diet-inflammation trialogue in depression. Curr Opin Psychiatry 30(5):369–377. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0000000000000350

Kotłowski R (2016) Use of Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 producing recombinant colicins for treatment of IBD patients. Med Hypotheses 93:8–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.MEHY.2016.05.002

Krauter EM, Linden DR, Sharkey KA, Mawe GM (2007) Synaptic plasticity in myenteric neurons of the guinea-pig distal colon: presynaptic mechanisms of inflammation-induced synaptic facilitation. J Physiol 581(2):787–800. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.2007.128082

Lasserre C, Colnot C, Bréchot C, Poirier F (1999) HIP/PAP gene, encoding a C-type lectin overexpressed in primary liver cancer, is expressed in nervous system as well as in intestine and pancreas of the postimplantation mouse embryo. Am J Pathol 154(5):1601–1610. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65413-2

Li Q, Montalban-Lopez M, Kuipers OP (2018) Increasing the antimicrobial activity of Nisin-based lantibiotics against gram-negative pathogens. Appl Environ Microbiol 84(12). https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00052-18

Lieb K, Walden J, Grunze H, Fiebich BL, Berger M, & Normann C (2004) Serum levels of substance P and response to antidepressant pharmacotherapy. Pharmacopsychiatry. Germany

Linden DR, Sharkey KA, Mawe GM (2004) Enhanced excitability of myenteric AH neurones in the inflamed guinea-pig distal colon. J Physiol 547(2):589–601. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.2002.035147

Lyte M, & Cryan JF (2014) Microbial endocrinology: the microbiota-gut-brain axis in health and disease. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-0987-4

Ma H (2016) Calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP). In Handbook of hormones (pp. 235–237). Elsevier Inc. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-801028-0.00171-9

Madhuri ST, Venugopal SK, Ghosh D, Gadepalli R, Dhawan B, Mukhopadhyay K (2009) In vitro antimicrobial activity of alpha-melanocyte stimulating hormone against major human pathogen Staphylococcus aureus. Peptides 30(9):1627–1635. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.peptides.2009.06.020

Margolis KG, Gershon MD (2016) Enteric neuronal regulation of intestinal inflammation. Trends Neurosci 39(9):614–624. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tins.2016.06.007

Martínez-Herrero S, Martínez A (2016) Adrenomedullin regulates intestinal physiology and pathophysiology. Domest Anim Endocrinol 56:S66–S83. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.DOMANIEND.2016.02.004

Martinez B, Rodriguez A, & Suarez E (2016) Antimicrobial peptides produced by bacteria: the bacteriocins. In New weapons to control bacterial growth. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-28368-5

Marutsuka K, Nawa Y, Asada Y, Hara S, Kitamura K, Eto T, Sumiyoshi A (2001) Adrenomedullin and proadrenomudullin N-terminal 20 peptide (PAMP) are present in human colonic epithelia and exert an antimicrobial effect. Exp Physiol 86(5):543–545. https://doi.org/10.1113/eph8602250

Masman MF, Rodriguez AM, Svetaz L, Zacchino SA, Somlai C, Csizmadia IG et al (2006) Synthesis and conformational analysis of His-Phe-Arg-Trp-NH2 and analogues with antifungal properties. Bioorg Med Chem 14(22):7604–7614. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmc.2006.07.007

Mason DY, Taylor CR (1975, February) The distribution of muramidase (lysozyme) in human tissues. J Clin Pathol 28:124–132

Micenková L, Frankovičová L, Jaborníková I, Bosák J, Dítě P, Šmarda J, Vrba M, Ševčíková A, Kmeťová M, Šmajs D (2018) Escherichia coli isolates from patients with inflammatory bowel disease: ExPEC virulence- and colicin-determinants are more frequent compared to healthy controls. Int J Med Microbiol 308(5):498–504. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IJMM.2018.04.008

Mijouin L, Hillion M, Ramdani Y, Jaouen T, Duclairoir-Poc C, Follet-Gueye, et al. (2013) Effects of a skin neuropeptide (substance P) on cutaneous microflora. PLoS One 8(11). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0078773

Miki T, Okada N, Hardt WD (2017) Inflammatory bactericidal lectin RegIIIβ: friend or foe for the host? Gut Microbes 9(2):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/19490976.2017.1387344

Mitchell MJ, King MR (2010) Neuropeptides: keeping the balance between pathogen immunity and immune tolerance. Curr Opin Pharmacol 10(4):473–481. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coph.2010.03.003

Morales-Medina JC, Dumont Y, Quirion R (2010) A possible role of neuropeptide Y in depression and stress. Brain Res 1314:194–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BRAINRES.2009.09.077

Mukherjee S, Zheng H, Derebe MG, Callenberg KM, Partch CL, Rollins D, Propheter DC, Rizo J, Grabe M, Jiang QX, Hooper LV (2013) Antibacterial membrane attack by a pore-forming intestinal C-type lectin. Nature 505:103. Retrieved from. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12729

N’Diaye A, Mijouin L, Hillion M, Diaz S, Konto-Ghiorghi Y, Percoco G, et al. (2016) Effect of substance P in Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis virulence: implication for skin homeostasis. Frontiers in Microbiology, 7(APR), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2016.00506

Nelson KB, Grether JK, Croen LA, Dambrosia JM, Dickens BF, Jelliffe LL, Hansen RL, Phillips TM (2001) Neuropeptides and neurotrophins in neonatal blood of children with autism or mental retardation. Ann Neurol 49(5):597–606

Nevalainen TJ, Graham GG, Scott KF (2008) Antibacterial actions of secreted phospholipases A2. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids 1781(1–2):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbalip.2007.12.001

Nevalainen TJ, Grönroos JM, Kallajoki M (1995) Expression of group II phospholipase A2 in the human gastrointestinal tract. Lab Invest 72(2):201–208 Retrieved from http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/7853853

Ohta K, Kajiya M, Zhu T, Nishi H, Mawardi H, Shin J et al (2011) Additive effects of Orexin B and vasoactive intestinal polypeptide on LL-37-mediated antimicrobial activities. J Neuroimmunol 233(1-2):37–45. https://doi.org/10.1021/nn300902w.Release

Parisot J, Carey S, Breukink E, Chan WC, Narbad A, Bonev B (2008) Molecular mechanism of target recognition by subtilin, a class I lanthionine antibiotic. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 52(2):612–618. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.00836-07

Pérez-Castells J, Martín-Santamaría S, Nieto L, Ramos A, Martínez A, De Pascual-Teresa B, Jiménez-Barbero J (2012) Structure of micelle-bound adrenomedullin: a first step toward the analysis of its interactions with receptors and small molecules. Biopolymers 97(1):45–53. https://doi.org/10.1002/bip.21700

Perez RH, Zendo T, Sonomoto K (2014) Novel bacteriocins from lactic acid bacteria (LAB): various structures and applications. Microb Cell Factories 13(Suppl 1):S3. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2859-13-S1-S3

Poirier AA, Aubé B, Côté M, Morin N, Di Paolo T, Soulet D (2016) Gastrointestinal dysfunctions in Parkinson’s disease: symptoms and treatments. Parkinson’s Disease 2016. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/6762528

Powers JPS, Hancock REW (2003) The relationship between peptide structure and antibacterial activity. Peptides 24(11):1681–1691. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.peptides.2003.08.023

Pusceddu MM, Murray K, Gareau MG (2018) Targeting the microbiota, from irritable bowel syndrome to mood disorders: focus on probiotics and prebiotics. Curr Pathobiology Rep 6(1):1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40139-018-0160-3

Rogers LA, Whittier EO (1928) Limiting factors in the lactic fermentation. J Bacteriol 16(4):211–229

Rowland I, Gibson G, Heinken A, Scott K, Swann J, Thiele I, Tuohy K (2018) Gut microbiota functions: metabolism of nutrients and other food components. Eur J Nutr 57(1):1–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-017-1445-8

Sassone-Corsi M, Nuccio SP, Liu H, Hernandez D, Vu CT, Takahashi AA, Edwards RA, Raffatellu M (2016) Microcins mediate competition among Enterobacteriaceae in the inflamed gut. Nature 540(7632):280–283. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature20557

Sato H, Feix JB (2006) Peptide-membrane interactions and mechanisms of membrane destruction by amphipathic α-helical antimicrobial peptides. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr 1758(9):1245–1256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.02.021

Schauber J, Svanholm C, Term??n, S., Iffland, K., Menzel, T., Scheppach, et al. (2003) Expression of the cathelicidin LL-37 is modulated by short chain fatty acids in colonocytes: relevance of signalling pathways. Gut 52(5):735–741. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.52.5.735

Singh M, Mukhopadhyay K (2014) Alpha-melanocyte stimulating hormone: an emerging anti-inflammatory antimicrobial peptide. Biomed Res Int 2014:874610. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/874610

Sipka A, Langner K, Seyfert HM, Schuberth HJ (2010) Substance P alters the in vitro LPS responsiveness of bovine monocytes and blood-derived macrophages. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 136(3–4):219–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetimm.2010.03.011

Sivieri K, Bassan J, Peixoto G, Monti R (2017) Gut microbiota and antimicrobial peptides. Curr Opin Food Sci 13:56–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cofs.2017.02.010

Smarda J, Smajs D (1998) Colicins - exocellular lethal proteins of Escherichia coli. Folia Microbiol 43(6):563–582. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02816372

Souza-Moreira L, Campos-Salinas J, Caro M, Gonzalez-Rey E (2011) Neuropeptides as pleiotropic modulators of the immune response. Neuroendocrinology 94(2):89–100. https://doi.org/10.1159/000328636

Strandwitz P (2018) Neurotransmitter modulation by the gut microbiota. Brain Res 1693:128–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2018.03.015

Strong DS, Cornbrooks CF, Roberts JA, Hoffman JM, Sharkey KA, Mawe GM (2010) Purinergic neuromuscular transmission is selectively attenuated in ulcerated regions of inflamed guinea pig distal colon. J Physiol 588(5):847–859. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.2009.185082

Sun M-F, Shen Y-Q (2018) Dysbiosis of gut microbiota and microbial metabolites in Parkinson’s disease. Ageing Res Rev 45:53–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ARR.2018.04.004

Svenningsson P, Pålhagen S, & Mathé AA (2017) Neuropeptide Y and calcitonin gene-related peptide in cerebrospinal fluid in Parkinson’s disease with comorbid depression versus patients with major depressive disorder. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 8(JUN), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00102

Taylor AM, Holscher HD (2018) A review of dietary and microbial connections to depression, anxiety, and stress. Nutr Neurosci:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/1028415X.2018.1493808

Tennoune N, Chan P, Breton J, Legrand R, Chabane YN, Akkermann K, Järv A, Ouelaa W, Takagi K, Ghouzali I, Francois M, Lucas N, Bole-Feysot C, Pestel-Caron M, do Rego JC, Vaudry D, Harro J, Dé E, Déchelotte P, Fetissov SO (2014) Bacterial ClpB heat-shock protein, an antigen-mimetic of the anorexigenic peptide α-MSH, at the origin of eating disorders. Transl Psychiatry 4(August):e458. https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2014.98

Thomas L, Scheidt HA, Bettio A, Huster D, Beck-Sickinger AG, Arnold K, Zschörnig O (2005) Membrane interaction of neuropeptide Y detected by EPR and NMR spectroscopy. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr 1714(2):103–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbamem.2005.06.012

Thornton, E., & Vink, R. (2008). The role of the neuropeptide substance P in the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease

Valore EV, & Ganz T (1992) Posttranslational processing of defensins in immature human myeloid cells. Blood, 79(6), 1538–1544. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1339298

van Heijenoort J (2007) Lipid intermediates in the biosynthesis of bacterial peptidoglycan. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 71(4):620–635. https://doi.org/10.1128/MMBR.00016-07

Váradi J, Harazin A, Fenyvesi F, Réti-Nagy K, Gogolák P, Vámosi G, Bácskay I, Fehér P, Ujhelyi Z, Vasvári G, Róka E, Haines D, Deli MA, Vecsernyés M (2017) Alpha-melanocyte stimulating hormone protects against cytokine-induced barrier damage in Caco-2 intestinal epithelial monolayers. PLoS One 12(1):e0170537. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0170537

Vouldoukis I, Shai Y, Nicolas P, Mor A (1996) Broad spectrum antibiotic activity of skin-PYY. FEBS Lett 380(3):237–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/0014-5793(96)00050-6

Vuong HE, Hsiao EY (2018) Emerging roles for the gut microbiome in autism spectrum disorder. Biol Psychiatry 81(5):411–423. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2016.08.024.Emerging

Wiedemann I, Böttiger T, Bonelli RR, Wiese A, Hagge SO, Gutsmann T et al (2006) The mode of action of the lantibiotic lacticin 3147—a complex mechanism involving specific interaction of two peptides and the cell wall precursor lipid II. Mol Microbiol 61(2):285–296. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05223.x

Wiedemann I, Breukink E, van Kraaij C, Kuipers OP, Bierbaum G, de Kruijff B, Sahl HG (2001) Specific binding of nisin to the peptidoglycan precursor lipid II combines pore formation and inhibition of cell wall biosynthesis for potent antibiotic activity. J Biol Chem 276(3):1772–1779. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M006770200

Xhindoli D, Pacor S, Benincasa M, Scocchi M, Gennaro R, Tossi A (2016) The human cathelicidin LL-37—a pore-forming antibacterial peptide and host-cell modulator. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr 1858(3):546–566. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbamem.2015.11.003

Xu C, Guo Y, Qiao X, Shang X, Niu W, Jin M et al (2017) Design, recombinant fusion expression and biological evaluation of vasoactive intestinal peptide analogue as novel antimicrobial agent. Molecules 22(11):1963. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules22111963

Yoo BB, & Mazmanian SK (2017) The enteric network: interactions between the immune and nervous systems of the gut https://doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2017.05.011

Zaiou M, Gallo RL (2002) Cathelicidins, essential gene-encoded mammalian antibiotics. J Mol Med 80(9):549–561. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00109-002-0350-6

Zhang LS, Davies SS (2016) Microbial metabolism of dietary components to bioactive metabolites: opportunities for new therapeutic interventions. Genome Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13073-016-0296-x

Acknowledgments

SEA is supported by Rosalind Franklin Fellowships, co-funded by the European Union and University of Groningen.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, JAS, SEA; writing–original draft, JAS, SEA; writing–review and editing, JAS; funding acquisition, SEA.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article belongs to a Special Issue on Microbiome in Psychiatry & Psychopharmacology.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Aresti Sanz, J., El Aidy, S. Microbiota and gut neuropeptides: a dual action of antimicrobial activity and neuroimmune response. Psychopharmacology 236, 1597–1609 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-019-05224-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-019-05224-0