Abstract

This paper investigates the effect of foreign bank entry on the export quality of firms. For this purpose, we mainly use the transaction data from the Chinese Customs Database and the production data from the Annual Survey of Industrial Firms of China during the years 2000–2006. The obtained data consists of 62,483 observations gathered from 19,888 firms. The results show that foreign bank entry enhanced the export quality of firms that are more externally financially dependent. This influence is stronger for non-state-owned firms and ordinary-trade firms than for the other types of firms. We further demonstrate that foreign bank entry is mainly through promoting innovation endeavors and improving the quality of intermediate inputs yielding to enhance the export quality of firms that have more external financial requirements.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Similar to Kose et al. (2010), the openness of the banking sector here means legal restrictions on foreign banks are deregulated.

Another significant reform in the financial market was the most recent deregulation of the restrictions on foreign banks in 2018. However, the COVID-19 pandemic slowed down the development of foreign banks as well as international trade, making a sample period after 2018 less suitable for examining the relationship between foreign bank entry and firm export quality.

For example, the endogenous problem may arise from the omitted variable biases. Foreign bank entry and the export quality of firms could be affected by the same regional and/or firm characteristics. In addition, there could be a simultaneity bias. The quality upgrading of the exports of firms would promote the upgrading of industrial structures in a region, while the upgraded industrial structures and the improved business environment could attract more foreign banks.

By the end of 2001, the restrictions were alleviated for Shenzhen, Shanghai, Dalian, and Tianjin; subsequently, at the end of 2002, Zhuhai, Guangzhou, Nanjing, Qingdao, and Wuhan were opened. Further openings occurred at the end of 2003 for Fuzhou, Jinan, Chongqing, and Chengdu. At the end of 2004, Beijing, Kunming, and Xiamen were opened and, finally, at the end of 2005, Ningbo, Shantou, Xi’an, and Shenyang were also accessible.

For example, if the banking sector’s openness to foreign banks enables firms to alleviate their financial constraints, these firms could lower their production costs and subsequently reduce their export prices. As a result, firms would increase their export volume without changing their exportation quality.

A bank is considered as foreign-owned if it is originated from a country or region outside of mainland China.

Between the end of 2001 to the end of 2003, the geographic restrictions on foreign banks for conducting RMB business were gradually removed in several cities, but foreign banks were still only permitted to carry out RMB business with foreign individuals and firms. Between the end of 2003 to the end of 2005, both the geographic and the client restrictions on foreign bank lending were gradually removed in several cities. Since the end of 2006, these bans were lifted in all cities. In this paper, we only consider the liberalization of geographic restrictions on foreign banks in China.

The sigma data were obtained from http://www.columbia.edu/~dew35/TradeElasticities/TradeElasticities.html. We also used the product-invariant elasticities of substitution in the robustness check (refer to A.1 in Appendix A). In addition, the mean (7.5) and median (2.8) of elasticities of substitution, provided by Broda and Weinstein (2006), were also used to respectively estimate the export quality. All the results indicate that our conclusion remained the same for different choices of elasticity of substitution.

We match different classifications on economic statistics based on their correlation table from https://unstats.un.org/unsd/classifications/Econ.

Since the end of 2003, the client restrictions have been lifted for all opened cities.

The main reason for using the sample period of 2000–2006 is that all the geographic restrictions on foreign bank lending in China were removed after the end of 2006. In addition, most of the existing works, based on CCD, also used the sample period of 2000–2006 (Liu and Qiu 2016; Zhang and Ouyang 2018).

To avoid measurement errors, we deleted firms with annual sales revenue below RMB 5 million and those that have less than eight employees or negative and zero total assets.

Our sample includes the following regions: Shenzhen, Shanghai, Xi’an, Dalian, Shenyang, Tianjin, Ningbo, Qingdao, Guangzhou, Shantou, Zhuhai, Xiamen, Beijing, Nanjing, Kunming, Wuhan, Chongqing, Jinan, Chengdu, Fuzhou, Guiyang, Lanzhou, Zhengzhou, Hangzhou, Nanning, Hefei, Shijiazhuang, Haerbin, Taiyuan, Yinchuan, Huhehaote, Changsha, Wulumuqi, Nanchang, Xining, Haikou, Lasa, and Changchun.

After controlling for the firm’s characteristics and a series of fixed effects, only 57,344 observations were included in the regressions.

In China, ordinary- and processing-trade exports account for more than 90% of the total exports (Tang et al. 2021). We only retained the ordinary- and processing-trade exports in our sample.

The R&D investment data were obtained from the ASIF database for the sample period of 2005–2007. He et al. (2018) provided the patent data for the sample period of 2000–2006.

For example, according to Eq. (4), if we want to estimate the quality of a product originating from an African country, we should use the disaggregate transaction data of that country.

As mentioned in the Appendix (A.1), the share of high-tech imported intermediate inputs can serve as a proxy for the quality of imported intermediate inputs (Lall 2000; Zhang and Ouyang 2018). The existing studies also point out that the unit price can well capture quality (e.g., Kugler and Verhoogen 2012; Feenstra and Romalis 2014; Fan et al. 2015; Fieler et al. 2018). For example, Bas and Strauss-Kahn (2015) used the unit price of imported intermediate inputs to reflect quality.

Because Shanghai and Shenzhen were opened to foreign banks before the end of 2001, we also deleted these two cities to conduct a robustness check. The result remained consistent with our main finding.

References

Aghion P, Askenazy P, Berman N, Cette G, Eymard L (2012) Credit constraints and the cyclicality of R&D investment: Evidence from France. J Eur Econ Assoc 10(5):1001–1024

Algieri B, Aquino A, Mannarino L (2018) Non-price competitiveness and financial drivers of exports: evidences from italian regions. Italian Econ J 4(1):107–133. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40797-016-0047-6

Ayyagari M, Demirgüç-Kunt A, Maksimovic V (2011) Firm innovation in emerging markets: The role of finance, governance, and competition. J Financ Quant Anal 46(6):1545–1580

Bas M, Strauss-Kahn V (2015) Input-trade liberalization, export prices and quality upgrading. J Int Econ 95(2):250–262

Berman N, Héricourt J (2010) Financial factors and the margins of trade: Evidence from cross-country firm-level data. J Dev Econ 93(2):206–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2009.11.006

Bermpei T, Kalyvas AN, Neri L, Russo A (2019) Will strangers help you enter? The effect of foreign bank presence on new firm entry. Journal of Financial Services Research 56(1):1–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10693-017-0286-1

Bloom N, Draca M, Reenen JV (2016) Trade induced technical change? The impact of Chinese imports on innovation, it and productivity. Rev Econ Stud 83(1):87–117. https://doi.org/10.1093/restud/rdv039

Bouët A, Vaubourg AG (2016) Financial constraints and international trade with endogenous mode of competition. J Bank Finance 68:179–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2016.03.007

Brandt L, Li HB (2003) Bank discrimination in transition economies: Ideology, information, or incentives? J Comp Econ 31:387–413. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0147-5967(03)00080-5

Broda C, Weinstein DE (2006) Globalization and the gains from variety. Q J Econ 121(2):541–585

Brodsky DA (1982) Arithmetic versus geometric effective exchange rates. Rev World Econ 118(3):546–562. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02706265

Calof JL (1994) The relationship between firm size and export behavior revisited. J Int Bus Stud 25:367–387

Chai J (2023) The impact of green innovation on export quality. Appl Econ Lett 30(10):1279–1286. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504851.2022.2045249

Chambers C, Kouvelis P, Semple J (2006) Quality-based competition, profitability, and variable costs. Manage Sci 52(12):1884–1895

Chor D, Manova K (2012) Off the cliff and back? Credit conditions and international trade during the global financial crisis. J Int Econ 87(1):117–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2011.04.001

Ciani A, Bartoli F (2013) Export quality upgrading and credit constraints. In Annual conference of European trade study group (ETSG). https://ideas.repec. org/p/zbw/dicedp/191.thml

Claessens S, Van Horen N (2021) Foreign banks and trade. Journal of Financial Intermediation 45:100856. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfi.2020.100856

Clarke GRG, Cull R, Pería MSM (2006) Foreign bank participation and access to credit across firms in developing countries. J Comp Econ 34(4):774–795. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jce.2006.08.001

Deng X, Li L (2020) Promoting or inhibiting? The impact of environmental regulation on corporate financial performance—An empirical analysis based on China. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(11):3828. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17113828

Detragiache E, Tressel T, Gupta P (2008) Foreign banks in poor countries: theory and evidence. Journal of Finance 63(5):2123–2160

Fan HC, Lai EL, Li YA (2015) Credit constraints, quality, and export prices: theory and evidence from China. J Comp Econ 43:390–416

Fang Y, Gu G, Li H (2015) The impact of financial development on the upgrading of China’s export technical sophistication. IEEP 12(2):257–280. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10368-014-0277-8

Feenstra RC, Romalis J (2014) International prices and endogenous quality. Q J Econ 129(2):477–527

Feng L, Li Z, Swenson DL (2016) The connection between imported intermediate inputs and exports: evidence from Chinese firms. J Int Econ 101:86–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2016.03.004

Fieler AC, Eslava M, Xu DY (2018) Trade, quality upgrading, and input linkages: theory and evidence from Colombia. Am Econ Rev 108(1):109–146. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20150796

Foellmi R, Legge S, Tiemann A (2021) Innovation and trade in the presence of credit constraints. Canadian J Econ 54(3):1168–1205. https://doi.org/10.1111/caje.12531

Gatimbu KK, Ogada MJ, Budambula N, Kariuki S (2018) Environmental sustainability and financial performance of the small-scale tea processors in Kenya. Bus Strateg Environ 27(8):1765–1771. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2243

Giannetti M, Ongena S (2009) Financial integration and firm performance: evidence from foreign bank entry in emerging markets. Rev Financ 13(2):181–223. https://doi.org/10.1093/rof/rfm019

Gormley T (2014) Costly Information, entry, and credit access. Journal of Economic Theory 154:633–667. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jet.2014.06.003

Gourdon J, Monjon S, Poncet S (2017) Incomplete VAT rebates to exporters: How do they affect China's export performance? Working Paper, No. hal-01496998

Guiso L, Sapienza P, Zingales L (2004) Does local financial development matter? Q J Econ 119:929–969

He ZL, Tong TW, Zhang YC, He WL (2018) Construction of a database linking sipo patents to firms in China’s annual survey of industrial enterprises 1998–2009. J Econ Manag Strat 27:579–606

Henn C, Papageorgiou MC, Spatafora MN (2013) Export quality in developing countries. International Monetary Fund.

Hsieh CT, Song Z (2015) Grasp the large, let go of the small: the transformation of the state sector in China. Brook Pap Econ Act 46(1):295–366. https://doi.org/10.1353/eca.2016.0005

Ju J, Yu X (2015) Productivity, profitability, production and export structures along the value chain in China. J Comp Econ 43(1):33–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jce.2014.11.008

Khandelwal AK, Schott PK, Wei SJ (2013) Trade liberalization and embedded institutional reform: evidence from Chinese exporters. Am Econ Rev 103(6):2169–2195. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.103.6.2169

Kose MA, Prasad E, Rogoff K, Wei SJ (2010) Financial globalization and economic policies. In: Rodrik D, Rosenzweig M (eds) Handbook of Development Economics. North-Holland, The Netherlands

Kroll M, Wright P, Heiens RA (1999) The contribution of product quality to competitive advantage: impacts on systematic variance and unexplained variance in returns. Strateg Manag J 20(4):375–384

Kroszner RS, Laeven L, Klingebiel D (2007) Banking crises, financial dependence, and growth. J Financ Econ 84(1):187–228

Kugler M, Verhoogen E (2009) Plants and imported inputs: New facts and an interpretation. Am Econ Rev 99(2):501–507

Kugler M, Verhoogen E (2012) Prices, plant size, and product quality. Rev Econ Stud 79(1):307–339. https://doi.org/10.1093/restud/rdr021

Lai T, Qian Z, Wang L (2016) WTO accession, foreign bank entry, and the productivity of Chinese manufacturing firms. J Comp Econ 44(2):326–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jce.2015.06.003

Lall S (2000) The technological structure and performance of developing country manufactured exports, 1985–98. Oxf Dev Stud 28(3):337–369. https://doi.org/10.1080/713688318

Levine R (1996) Foreign banks, financial development, and economic growth. J Econ Literat 35:224–254

Li H, Ma H, Xu Y (2015) How do exchange rate movements affect Chinese exports? — A firm-level investigation. J Int Econ 97(1):148–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2015.04.006

Li G, Li J, Zheng Y, Egger PH (2021) Does property rights protection affect export quality? Evidence from a property law enactment. J Econ Behav Organ 183:811–832. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2020.10.023

Lin H (2011) Foreign bank entry and firms’ access to bank credit: Evidence from China. J Bank Finance 35(4):1000–1010

Liu QD, Qiu LD (2016) Intermediate input imports and innovations: evidence from Chinese firms’ patent filings. J Int Econ 103:166–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2016.09.009

Liu Q, Cheng L, Shao Z, Chen QP (2017) Financing constraint, export model and transformation and upgrading of foreign trade. Econ Res J 5:75–88

Manova K (2008) Credit constraints, equity market liberalizations and international trade. J Int Econ 76(1):33–47

Manova K (2013) Credit Constraints, Heterogeneous Firms, and International Trade. Rev Econ Stud 80(2):711–744

Manova K, Wei SJ, Zhang Z (2015) Firm exports and multinational activity under credit constraints. Rev Econ Stat 97(3):574–588. https://doi.org/10.2307/43554996

Muûls M (2015) Exporters, importers and credit constraints. J Int Econ 95:333–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2014.12.003

Ndubuisi G, Owusu S (2021) How important is GVC participation to export upgrading? The World Econ 44(10):2887–2908. https://doi.org/10.1111/twec.13102

Nguyen CP, Su TD (2021) Export quality dynamics: multidimensional evidence of fi-nancial development. The World Economy 44(8):2319–2343. https://doi.org/10.1111/twec.13103

Nucci F, Pietrovito F, Pozzolo AF (2021) Imports and credit rationing: a firm-level investigation. The World Economy 44(11):3141–3167. https://doi.org/10.1111/twec.13059

Pan X, Li S (2016) Dynamic optimal control of process–product innovation with learning by doing. Eur J Oper Res 248(1):136–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2015.07.007

Riding A, Orser BJ, Spence M, Belanger B (2012) Financing new venture exporters. Small Bus Econ 38:147–163

Roper S, Love JH (2002) Innovation and export performance: evidence from the UK and German manufacturing plants. Res Policy 31(7):1087–1102. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0048-7333(01)00175-5

Shang H, Xing YL (2020) Banking integration and firm innovation: evidence from foreign bank entry, Working Paper

Sharma P, Cheng LT, Leung TY (2020) Impact of political connections on Chinese export firms’ performance–Lessons for other emerging markets. J Bus Res 106:24–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.08.037

Tang B, Gao B, Ma J (2021) The impact of export VAT rebates on firm productivity: evidence from China. The World Economy 44(10):2798–2820. https://doi.org/10.1111/twec.13076

Xu J, Mao Q (2018) On the relationship between intermediate input imports and export quality in China. Econ Transit 26(3):429–467

Ye J, Zhang A, Dong Y (2019) Banking reform and industry structure: evidence from China. J Bank Finance 104:70–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2019.05.004

Yu M (2014) Processing trade, tariff reductions and firm productivity: Evidence from Chinese firms. Econ J 125(585):943–988

Zhang T, Ouyang P (2018) Is RMB appreciation a nightmare for the Chinese firms? An analysis on firm profitability and exchange rate. Int Rev Econ Financ 54:27–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iref.2017.05.003

Zou J, Shen G, Gong Y (2019) The effect of value-added tax on leverage: Evidence from China’s value-added tax reform. China Econ Rev 54:135–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2018.10.013

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the valuable suggestions of the two anonymous reviewers and the editor Kumbhakar. We would also like to thank Peng Huang, Jerome Henry and the seminar participants in the Cross-Country Perspectives in Finance conference and World Finance and Banking Symposium for many useful comments. All errors are our own. This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 72203185), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. JBK2101028) and the Guanghua Talent Project of Southwestern University of Finance and Economics.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix A

1.1 Robustness check

1.1.1 Alternative measure of key variables

An alternative measure of export quality. In our baseline model, the elasticities of substitution vary among varieties (Broda and Weinstein 2006). In this study, a constant elasticity of substitution was deployed to estimate the export quality. In Column (1) of Table

7, \(\sigma { = 4}\) was used to re-estimate the export equality, as defined by Khandelwal et al. (2013). The result reinforces our baseline result.

In Sect. 3.1, we mentioned that most firms export several products classified in HS 6-digit codes; therefore, we used the weighted average of export quality to calculate the export quality of a firm (refer to Eq. (5)). To conduct a robustness check, we considered the quality of a firm’s main product (i.e., the largest export product) as its export quality. We report the result in Column (2) of Table 7; it reveals that there still exist a significantly positive coefficient associated with the interaction term although its magnitude decreases.

We also adopted the percentage of high-technology exports relative to the total exports as the measure of export quality for each firm. As mentioned by Lall (2000), if a firm shifts its export structure from low-technology to high-technology products, the export quality of this firm is improved. We applied Lall (2000) and Zhang and Ouyang (2018) methods to calculate the proportion of exports with high technology for each firm. The result is reported in Column (3) of Table 7. Once again, the result was found to be consistent with our baseline result.

An alternative measure of EFD. In our baseline result, we used the weighted average of the EFD for the sectors covered by a firm to calculate the EFD of that firm. To conduct a robustness check, we applied the sector of the main product of a firm (i.e., the largest export product) in the initial year as the essential sector of the firm, and we adopted the EFD of that sector to denote its dependence on external financing. As presented in Column (4) of Table 7, the coefficient associated with FB × EFD remained significant and positive; thus, the measurement of a firm’s EFD did not drive our findings.

So far, we have used the U.S.-based EFD measure to conduct our estimations. As a robustness check, we replaced the U.S.-based measure with that calculated using the Chinese data. Referring to Kroszner et al. (2007) and Manova et al. (2015), the EFD of the firms is defined as the ratio of their liabilities to assets. In China, the external financing of firms is mainly obtained from bank loans; thus, the liabilities of firms can basically reflect their external funds derived from banks (Ye et al. 2019). To eliminate the concern of endogeneity, we used the liability ratio for each firm in the initial year to denote the level of a firm’s EFD. The related result is reported in Column (5) of Table 7, and it reveals that foreign bank entry have significantly enhanced the export quality of firms with greater EFD.

1.2 More controls

City-level controls. In the baseline results, our identification strategy can alleviate the omitted variable problem. However, one may still wonder whether the export quality of firms is affected by other funding sources that are connected to the funding received from foreign banks. To address this concern, we introduce a series of additional city-level controls to capture the effects of other sources of financing on the firms’ export quality. The city-level controls include the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita, the number of domestic banking branches, the scale of the Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), and the government budget expenditure. The results are reported in Column (1) in Table

8. These findings prove that our main results still hold even when considering the other financing sources of firms.

Firm-level controls. In addition, we introduce other firm-level features, which may also impact the firms’ export quality to our baseline results, including firm age and the basic technical ability measured by intangible assets. The results, reported in Column (2) of Table 8, show that they are consistent with our baseline results.

1.3 Lagged explanatory variables

One may consider that firms may require time to adjust their export quality; hence, time-lagged independent variables should be used in the estimations. In this work, we alleviate this concern by using our identification strategy (refer to Sect. 4.2), which captures the average treatment effects after allowing foreign bank entry. However, to make our estimation more robust, we re-regressed the export quality of firms on the one-year-lagged explanatory variables displayed in Column (3) of Table 8 where we lagged behind all of the explanatory variables by one year. Once again, our main result remained robust.

1.4 Alternative samples

A sample including all cities. In the baseline, we included China’s main cities (38 cities) to reduce the difference between the treatment and control groups to the maximum possible extent. In this subsection, we used a sample that includes all cities (223 cities) to re-estimate our baseline where Column (4) in Table 8 presents the result. The magnitude of the coefficient of FB × EFD was close to the values in Column (6) of Table 8. Therefore, the findings prove that our method is robust.

A sample includes only “opened cities.” As mentioned in Sect. 4.3, our sample included the “opened cities” selected by the government as well as cities that were not opened to foreign banks until the end of 2006 but were very similar to the “opened cities”. However, the “opened cities” and “non-opened cities” may still have differences in some aspects even if there were no policy shocks. To make the treatment and control groups more similar before foreign bank entry, we used a sample that included only the “opened cities” before the end of 2006. Thus, the coefficient of FB × EFD presented in Column (5) of Table 8 remained positive and significant. Therefore, our baseline results are robust.Footnote 21

Appendix B

External financial dependence Table 9.

Appendix C

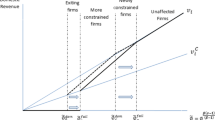

The estimated export quality (Fig. 1 and Table 10).

The correlation between price and quality. Note: The data are in firm-product-country-year level. We use more about 300 million observations from Chinese Customs Data to estimate Eq. (4). We allow the substitution elasticities vary across varieties and the substitution elasticities is from Broda and Weinstein (2006)

Appendix D

Firm-level exchange rate.

A firm’s real effective exchange rate is computed following Brodsky (1982):

where c is the firm f’s export destination in one year, C denotes the number of export destinations in one year, \(E_{ct}\) represents the nominal exchange rate of RMB with regard to the currency for country c in year t, \(E_{c}\) indicates the nominal exchange rate in the initial year, \(CPI_{t}\) denotes China’s Consumer Price Index (CPI) in year t, \(CPI_{ct}\) represents the country c’s CPI in that year, and \(\frac{{y_{c} }}{y}\) is the firm f’s share of export to country c initially, which is used as a weight. Therefore, \(REER_{ft}\) is the real effective exchange rate weighted by firms’ export. If a firm faces RMB appreciation currently, the \(REER_{ft}\) value will increase.

Appendix E

Foreign bank entry and export quality over time (Table 11 and Figs. 2 and 3).

Appendix F

Foreign bank entry and firms’ access to bank loans.

Since the external financing of Chinese firms is mainly from bank loans, firms’ liabilities can essentially indicate their external funds derived from banks (Ye et al. 2019). Therefore, the results proposed in Table

12 suggest that foreign bank entry increases both the long-term bank loans and total bank loans of domestic firms.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, T., Xing, Y. & Shang, H. Foreign bank entry and export quality upgrading: evidence from a quasi-natural experiment set in China. Empir Econ 66, 1975–2005 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-023-02513-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-023-02513-8