Abstract

Purpose

Meniscal injuries are common. Outside-in meniscal repair is one of the techniques advocated for the management of traumatic meniscal tears. This systematic review investigated the outcomes of the outside-in repair technique for the management of traumatic tears of the menisci. The outcomes of interest were to investigate whether PROMs improved and to evaluate the rate of complications.

Methods

Following the 2020 PRISMA statement, in May 2023, PubMed, Web of Science, Google Scholar, and Embase were accessed with no time constraints. All the clinical investigations which reported data on meniscal repair using the outside-in technique were considered for inclusion. Only studies which reported data on acute traumatic meniscal tears in adults were considered. Only studies which reported a minimum of 24 months of follow-up were eligible.

Results

Data from 458 patients were extracted. 34% (155 of 458) were women. 65% (297 of 458) of tears involved the medial meniscus. The mean operative time was 52.9 ± 13.6 min. Patients returned to their normal activities at 4.8 ± 0.8 months. At a mean of 67-month follow-up, all PROMs of interest improved: Tegner scale (P = 0.003), Lysholm score (P < 0.0001), International Knee Documentation Committee (P < 0.0001). 5.9% (27 of 458) of repairs were considered failures. Four of 186 (2.2%) patients experienced a re-injury, and 5 of 458 (1.1%) patients required re-operation.

Conclusion

Meniscal repair using the outside-in technique can be effectively performed to improve the quality of life and the activity level of patients with acute meniscal tears.

Level of evidence

Level IV.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The menisci are wedge-shaped fibrocartilages which ensure smooth articulation and redistribution of load within the tibiofemoral joint. Structurally, menisci consist predominantly of type I collagen in addition to proteoglycans and elastin [18, 65]. Shock absorption during gait and increasing joint stability are other important functions of the menisci [45]. The lateral and medial menisci differ in shape, percentage of tibial plateau coverage, and load transfer on the medial and lateral compartments during distinct knee movements [30, 34]. The approximate estimated incidence of symptomatic meniscal tears is 60 per 100,000 people [2, 7]. Male adults older than 40 years are more at risk to develop degenerative meniscal tears [19, 35]. Acute meniscal injuries are more prevalent in younger and active patients [6, 35, 65]. Management of meniscal tears depends on patient characteristics and the aetiology, morphology, and location of the tear [4, 7]. In patients with symptomatic meniscal tears refractory to conservative management or in those with mechanical symptoms, arthroscopy may be recommended [33, 43, 63]. When possible, meniscal repair is advocated over meniscectomy [32, 66]. Compared to meniscal repair, meniscectomy is associated with worse outcomes, faster osteoarthritis progression, and lower midterm cost-effectiveness [14, 15, 44, 52].

All-inside, inside-out, and outside-in meniscal repair are the most common techniques of meniscal repair [58, 61]. The outside-in technique was first described by Warren et al. to decrease the risk of peroneal nerve injury [64]. The most common indication is an anterior horn tear, given the difficulty of reaching this area using the all-inside technique [37, 53]. The lesion must be in the red-red or red-white zone, although successful meniscal repairs have been described in the white–white zone using fibrin clot augmentation [13, 36, 60]. The surgical technique entails passing two needles, from outside inward, through the capsule and the meniscal tear [29, 51]. One needle carries a loop of thread or metal, and the other the suture [28, 50, 68]. The most common complications are stiffness, failure of meniscal healing, and neurovascular damage [21, 39]. To the best of our knowledge, an updated systematic review on the efficacy and safety of outside-in meniscal repair is missing. Therefore, this systematic review investigated the outcomes of the outside-in repair technique for traumatic tears of the menisci. The outcomes of interest were to investigate whether the outside-in repair is associated with an improvement in PROMs and to evaluate the rate of complications.

Material and methods

Eligibility criteria

All the clinical investigations which reported data on meniscal repair using the outside-in technique were considered for inclusion. Studies which reported data on other meniscal repair methods (inside-out, all-inside) or arthroscopic meniscectomy (partial or total) were not suitable. Given the author’s language capabilities, articles in English, German, Italian, French, and Spanish were eligible. Only studies with levels I to IV of evidence, according to the Oxford Centre of Evidence-Based Medicine [26], were considered. Commentaries, abstracts, revisions, opinions, editorials, and letters were not eligible. Biomechanical studies on cadavers or animals were not eligible, nor were in vitro studies. Only studies which reported data on traumatic meniscal tears in adults were considered. Studies which reported data on degenerative tears or on adults older than 45 years were not considered. Only studies which reported a minimum of 24 months of follow-up were eligible. Missing quantitative data on the outcomes of interest warranted the exclusion from the present investigation.

Search strategy

This study followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: the 2020 PRISMA statement [47]. The PICOT algorithm was preliminarily established:

-

P (Problem): traumatic meniscal tears;

-

I (Intervention): meniscal repair;

-

C (Comparison): outside-in technique;

-

O (Outcomes): PROMs, rate of re-injury, failure, and revision surgery.

-

T (Timing): minimum 24 months follow-up.

In May 2023, PubMed, Web of Science, Google Scholar, and Embase were accessed with no time constraints. These keywords were given in the search bar of each database using the Boolean operator AND/OR as follows: (meniscus OR meniscal OR menisci) AND (injury OR tear OR rupture OR torn OR laceration) AND outside-in AND (PROMs OR outcome OR surgery OR Tegner OR Lysholm OR IKDC OR pain OR symptoms OR complications OR failure OR reoperation). No additional filters were for the search.

Selection and data collection

Two authors (MP and MC) independently performed data selection. All the resulting titles were screened by hand. If the titles matched the topic, the abstract was accessed. If the abstract matched the topic, the full text of the article was accessed. If the full text was not accessible, the article was excluded. The bibliographies were also screened by hand to identify further studies. All the resulting articles were assessed, and their eligibility was discussed. In case of disagreements, a third author took the final decision (NM).

Data items

Two authors (MP and MC) separately performed data extraction. The study generalities and the patient demographic at baseline (author, year of publication, journal, mean length of the follow-up, number of patients, mean age, mean BMI) were collected. Data concerning the following PROMs were collected at baseline and at the last follow-up: Tegner Activity Scale [10], Lysholm Knee Scoring Scale [40], and International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) [25]. The minimum clinically important difference (MCID) for the Lysholm score was 10/100, 15/100 for the IKDC, and 0.5/10 for the Tegner score [3, 27, 46]. The rate of complications (re-tear, re-operations, failure) was also collected. Failures were defined as the presence of symptomatic re-tears which impair the quality of life and sport participation and required additional surgery.

Assessment of the risk of bias

To assess the methodological quality, the Coleman Methodology Score (CMS) was used. The CMS is divided into parts A and B. The first part evaluated the study size, mean follow-up, surgical approach, type of study, description of the diagnosis, surgical technique, and post-operative rehabilitation. The second part evaluated the outcome criteria, the procedure for assessing outcomes, and the description of the subject selection process. The CMS resulted in a value between 0 (poor quality) and 100 (excellent quality). Values of CMS > 60/100 are considered satisfactory.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analyses were performed by the main author (FM) following the recommendations of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [24]. For descriptive statistics, mean and standard deviation were used. To evaluate the improvement from baseline to the last follow-up, the SPSS software was used. The mean difference (MD) was calculated, with 95% confidence interval (CI). The paired t-test was performed with values of P < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

Study selection

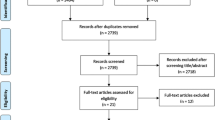

The literature search resulted in 1,418 studies. Of them, 604 were excluded as they were duplicates. A further 794 studies were excluded as they did not match the eligibility criteria: not matching the topic (N = 278), not reporting data on meniscal repair using the outside-in technique (N = 179), inappropriate study design/study type (N = 311), reporting data on degenerative tears or reporting data on adults older than 45 years (N = 11), follow-up shorter than 24 months (N = 9), language limitations (N = 6). A further 11 studies were excluded as they did not report quantitative data on the outcomes of interest. Finally, nine clinical investigations were included. The results of the literature search are shown in Fig. 1.

Risk of bias assessment

The study size and the length of the follow-up were appropriate in most articles. All authors investigated only the outside-in technique. 66% (6 of 9) of studies were retrospective, and 33% (3 of 9) were prospective. Moreover, no study was randomised, increasing the risk of selection bias. The description of diagnosis and surgical technique was adequate in most studies, whereas information on post-operative rehabilitation was barely reported. The outcome criteria and procedures for assessing outcomes were reliable in most studies. The description of the subject selection process was often adequately described. The CMS resulted in 66 ± 8 points, attesting a good quality of the methodology. The CMS related to each study is reported in Table 1.

Study characteristics and results of individual studies

Data from 458 patients were extracted. 34% (155 of 458) were women. The mean length of follow-up was 67.3 ± 74 months. 65% (297 of 458) of the meniscal tears were medial. The mean operative time was 52.9 ± 13.6 min. Patients returned to their normal activities at 4.8 ± 0.8 months from the index procedure. The generalities and demographics of the included studies are shown in Table 1.

Synthesis of results

At last follow-up, all PROMs of interest were statistically improved (Table 2): Tegner scale (MD 0.7; P = 0.003), Lysholm score (MD 21.4; P < 0.0001), IKDC (MD 28.9; P < 0.0001).

Complications

5.9% (27 of 458) or repair resulted in failures. The re-injury rate was 2.2% (4 of 186), and 1.1% (5 of 458) of patients required a re-operation.

Discussion

According to the main findings of the present study, meniscal repair using the outside-in technique achieves a statistically significant improvement in the Tegner Activity Scale, Lysholm Knee Scoring Scale, and IKDC. The improvement in PROMs overcome their MCID in all comparisons [3, 27, 46], but in 27 of 458 patients (5.9%) failures occurred. Four of 186 (2.2%) patients experienced a re-injury, and 5 of 458 (1.1%) patients required re-operation. However, among the included studies, only a few articles reported information on complications, and the real safety of the outside-in meniscal repair remains not fully clarified.

Biedert et al. [8] studied 40 patients, divided into four groups, based on the treatment received. Conservative management, arthroscopic suture repair, partial meniscectomy and partial meniscectomy combined with fibrin clot. A statistically significant improvement in functional scores was found in the suture repair group compared with the conservatively managed group. Patients who had undergone partial meniscectomy had better clinical outcomes than the meniscal suture group, and no patient suffered any post-operative complications. These outcomes can be related to the length of the follow-up [8]. The short-term outcomes are best in partial meniscectomy, but partial meniscectomy is associated with osteoarthritis progression [1, 16, 52, 55]. Lee et al. [38] studied meniscal sutures and partial meniscectomy, comparing the 18 months of follow-up and the follow-up after 18 months. At early follow-up, partial meniscectomy showed better clinical outcomes than meniscal sutures. At late follow-up, the IKCD and Tegner score were significantly better in the meniscal suture group than in the partial meniscectomy group. The scores of partial meniscectomy tended to decline over time, while the scores of meniscal suture remained stable. A partial meniscectomy removes the origin of the pain immediately after the surgery, while a meniscal suture requires time for healing [38]. Better clinical outcome was evident in patients undergoing simultaneous meniscal repair and ACL reconstruction than in patients having an isolated meniscal repair. The release of cytokines and growth factors after the drilling of bone tunnels could improve meniscal healing [22, 56]. Pogorelic et al. [50] conducted a study on adolescents and analysed the result of outside-in suturing and all-inside dart fixation. Excellent results were obtained in both groups, and clinical outcomes were comparable. Dart fixation is used preferably in posterior horn lesions, but darts can cause cartilage injury, while outside-in suturing is used preferably in anterior horn lesions [51, 57]. Majewski et al. [41] analysed the long-term effects of meniscal repair in 88 patients with a mean follow-up of 10 years (5–17 years). In 24% of patients, a traumatic or degenerative meniscal re-tear occurred. A statistically significant difference was found in the progression of osteoarthritis between the injured and the non-injured knee.

The rate of knee osteoarthritis after meniscal repair is higher compared to the general population [48]. However, in a study with over 20 years of follow-up, the longest follow-up to date, there was no statistically significant difference in osteoarthritis progression between the operated knee and the contralateral knee [11]. No signs of knee malalignment were found in the operated knees [11]. Two studies evaluated meniscal healing using post-operative MRI [51, 68]. Cereus et al. [51] showed healing in 7 of 8 patients, according to clinical tests and imaging, after 24 months of follow-up. In Zhou et al. study [68], post-operative MRI showed complete healing in 28 of 29 patients. A second-look arthroscopy was performed on 22 patients after 13 months. A total of 19 patients showed complete healing and 3 patients partial healing. No failure of healing was found. Domzalsky et al. [13] analysed the influence of smoking on meniscal healing. A prolonged time of return to daily and sport activities and worst functional scores were found among smokers [9]. Blood supply during meniscal healing is compromised in smokers [5, 20, 59].

The present systematic review has several limitations. The retrospective nature of most studies, along with the limited sample size and length of follow-up, represent important limitations. Between studies heterogeneities are evident. Three studies excluded patients with a concomitant ACL injury [13, 41, 51]. As stated above, ACL reconstruction favourable influences meniscal healing [38]. The location of meniscal tears was not homogeneous among the studies. Two studies analysed only anterior horn tears [38, 51]. One study analysed only lateral meniscus posterior root tears [68]. The outside-in technique is the most appropriate for anterior horn tears because it allows a direct approach to the lesion and a stable fixation construct [53]. One study included only longitudinal meniscal tears [41]. Characterisation of a meniscal tear is important because vertical and longitudinal tears are most suitable for outside-in suture [62]. In one study, an arthrotomy was used [11]. The longest-term follow-up of this study permits a comprehensive view of outside-in long-term results. Zhou et al. [68] utilised a side-to-side surgical technique. This technique allows an anatomic repair and does not change the meniscus physiological properties after a posterior horn lesion [31]. The literature shows little agreement on guidelines on rehabilitation after meniscal repair [12, 23, 54, 67]. Weight-bearing was not allowed in four of the included studies for the first 2–6 weeks [13, 38, 51, 68]. In two studies, partial weight bearing was allowed for the first 6 weeks [8, 41]. In two studies, full weight bearing was allowed immediately after surgery [11, 42]. Limitation in knee flexion was present in all the rehabilitation protocols, for 2–6 weeks, involving a gradual return to total knee flexion. Pogorelic et al. [50] did not specify their rehabilitation protocol. A recent systematic review analysed the rehabilitation protocol in 88 studies after meniscal repair [17]. In two-thirds of the included studies, partial weight bearing was allowed within the first week. In 23.4% of the studies, full weight bearing was allowed at 6 weeks after surgery. In one-third of the studies, full flexion was allowed at 6 weeks after surgery. Only three studies presented over 5 years of follow-up [11, 41, 42]. The prevalence of meniscal re-rupture can be influenced by the length of follow-up [49].

Concluding, the present systematic review indicates that meniscal repair using the outside-in technique can be effectively performed to improve the quality of life and the activity level of patients with acute meniscal tears. However, additional investigations are required to properly establish the safety profile of such procedure.

Conclusion

Meniscal repair using the outside-in technique was associated with an improvement in the Tegner Activity Scale, Lysholm Knee Scoring Scale, and IKDC. 5.9% were considered failures. Four of 186 (2.2%) patients experienced a re-injury, and 5 of 458 (1.1%) patients required re-operation.

Availability of data and materials

The data underlying this article are available within the article.

Abbreviations

- FU:

-

Follow-up

- SE:

-

Standard error

- CI:

-

Confidence of interval

- PROM:

-

Patient-reported outcome measure

- IKDC:

-

International knee documentation committee

- MD:

-

Mean difference

- CMS:

-

Coleman methodology score

- MCID:

-

Minimum clinically important difference

References

Abram SGF, Hopewell S, Monk AP, Bayliss LE, Beard DJ, Price AJ (2020) Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy for meniscal tears of the knee: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med 54:652–663

Adams BG, Houston MN, Cameron KL (2021) The epidemiology of meniscus injury. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev 29:e24–e33

Agarwalla A, Liu JN, Garcia GH, Gowd AK, Puzzitiello RN, Yanke AB et al (2021) Return to sport following isolated lateral opening wedge distal femoral osteotomy. Cartilage 13:846S-852S

Avila A, Vasavada K, Shankar DS, Petrera M, Jazrawi LM, Strauss EJ (2022) Current controversies in arthroscopic partial meniscectomy. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 15:336–343

Benjamin RM (2011) Exposure to tobacco smoke causes immediate damage: a report of the Surgeon General. Public Health Rep 126:158–159

Bernard CD, Kennedy NI, Tagliero AJ, Camp CL, Saris DBF, Levy BA et al (2021) Medial Meniscus Posterior Root Tear Treatment: Response. Am J Sports Med 49:NP7–NP8

Bhan K (2020) Meniscal tears: current understanding, diagnosis, and management. Cureus 12:e8590

Biedert RM (2000) Treatment of intrasubstance meniscal lesions: a randomized prospective study of four different methods. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 8:104–108

Blackwell R, Schmitt LC, Flanigan DC, Magnussen RA (2016) Smoking increases the risk of early meniscus repair failure. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 24:1540–1543

Briggs KK, Lysholm J, Tegner Y, Rodkey WG, Kocher MS, Steadman JR (2009) The reliability, validity, and responsiveness of the Lysholm score and Tegner activity scale for anterior cruciate ligament injuries of the knee: 25 years later. Am J Sports Med 37:890–897

Brucker PU, von Campe A, Meyer DC, Arbab D, Stanek L, Koch PP (2011) Clinical and radiological results 21 years following successful, isolated, open meniscal repair in stable knee joints. Knee 18:396–401

Carder SL, Messamore WG, Scheffer DR, Giusti NE, Schroeppel JP, Mullen S et al (2021) Publicly available rehabilitation protocols designated for meniscal repairs are highly variable. Arthrosc Sports Med Rehabil 3:e411–e419

Domzalski M, Muszynski K, Mostowy M, Wojtowicz J, Garlinska A (2021) Smoking is associated with prolonged time of the return to daily and sport activities and decreased knee function after meniscus repair with outside-in technique: Retrospective cohort study. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 29:23094990211012290

Driban JB, Harkey MS, Barbe MF, Ward RJ, MacKay JW, Davis JE et al (2020) Risk factors and the natural history of accelerated knee osteoarthritis: a narrative review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 21:332

Duethman NC, Wilbur RR, Song BM, Stuart MJ, Levy BA, Camp CL et al (2021) Lateral meniscal tears in young patients: a comparison of meniscectomy and surgical repair. Orthop J Sports Med 9:23259671211046056

Feeley BT, Lau BC (2018) Biomechanics and clinical outcomes of partial meniscectomy. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 26:853–863

Fried JW, Manjunath AK, Hurley ET, Jazrawi LM, Strauss EJ, Campbell KA (2021) Return-to-play and rehabilitation protocols following isolated meniscal repair-a systematic review. Arthrosc Sports Med Rehabil 3:e241–e247

Gee SM, Posner M (2021) Meniscus anatomy and basic science. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev 29:e18–e23

Geffroy L (2021) Meniscal pathology in children and adolescents. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 107:102775

Golbidi S, Edvinsson L, Laher I (2020) Smoking and endothelial dysfunction. Curr Vasc Pharmacol 18:1–11

Gousopoulos L, Grob C, Ahrens P, Levy Y, Vieira TD, Sonnery-Cottet B (2022) How to avoid iatrogenic saphenous nerve injury during outside-in or inside-out medial meniscus sutures. Arthrosc Tech 11:e127–e132

Gousopoulos L, Hopper GP, Saithna A, Grob C, Levy Y, Haidar I et al (2022) Suture hook versus all-inside repair for longitudinal tears of the posterior horn of the medial meniscus concomitant to anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a matched-pair analysis From the SANTI study group. Am J Sports Med 50:2357–2366

Harput G, Guney-Deniz H, Nyland J, Kocabey Y (2020) Postoperative rehabilitation and outcomes following arthroscopic isolated meniscus repairs: a systematic review. Phys Ther Sport 45:76–85

Higgins JPT TJ, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (2022) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.2. Cochrane 2021. Available from www.training.cochrane.org/handbook. Accessed on February 2022

Higgins LD, Taylor MK, Park D, Ghodadra N, Marchant M, Pietrobon R et al (2007) Reliability and validity of the International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) Subjective Knee Form. Joint Bone Spine 74:594–599

Howick J CI, Glasziou P, Greenhalgh T, Carl Heneghan, Liberati A, Moschetti I, Phillips B, Thornton H, Goddard O, Hodgkinson M (2011) The 2011 Oxford CEBM Levels of Evidence. Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. Available at https://www.cebm.net/index.aspx?o=5653

Jones KJ, Kelley BV, Arshi A, McAllister DR, Fabricant PD (2019) Comparative effectiveness of cartilage repair with respect to the minimal clinically important difference. Am J Sports Med 47:3284–3293

Joshi A, Basukala B, Singh N, Hama B, Bista R, Pradhan I (2020) Outside-in repair of longitudinal tear of medial meniscus: suture shuttle technique. Arthrosc Tech 9:e407–e417

Kawada K, Furumatsu T, Tamura M, Xue H, Higashihara N, Kintaka K et al (2023) Effectivity of the outside-in pie-crusting technique and an all-inside meniscal repair device in the repair of ramp lesions. Arthrosc Tech 12:e273–e278

Kennedy MI, Strauss M, LaPrade RF (2020) Injury of the meniscus root. Clin Sports Med 39:57–68

Koenig JH, Ranawat AS, Umans HR, Difelice GS (2009) Meniscal root tears: diagnosis and treatment. Arthroscopy 25:1025–1032

Kopf S, Beaufils P, Hirschmann MT, Rotigliano N, Ollivier M, Pereira H et al (2020) Management of traumatic meniscus tears: the 2019 ESSKA meniscus consensus. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 28:1177–1194

Kopf S, Sava MP, Starke C, Becker R (2020) The menisci and articular cartilage: a life-long fascination. EFORT Open Rev 5:652–662

Krych AJ, Hevesi M, Leland DP, Stuart MJ (2020) Meniscal root injuries. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 28:491–499

Kunze KN, Wright-Chisem J, Polce EM, DePhillipo NN, LaPrade RF, Chahla J (2021) Risk factors for ramp lesions of the medial meniscus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med 49:3749–3757

Laddha MS, Shingane D (2022) Modified outside-in repair technique for chronic retracted, unstable bucket-handle anterior horn lateral meniscal tear. Arthrosc Tech 11:e1747–e1752

Laupattarakasem P, Laupattarakasem W (2020) Hybrid inside-out-outside-in meniscal repair through a small skin incision. Arthrosc Tech 9:e1957–e1965

Lee WQ, Gan JZ, Lie DTT (2019) Save the meniscus - Clinical outcomes of meniscectomy versus meniscal repair. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 27:2309499019849813

Leyes M, Flores-Lozano C, de Rus I, Salvador MG, Buenadicha EM, Villarreal-Villarreal G (2021) Repair of the posterior lateral meniscal root tear: suture anchor fixation through the outside-in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction femoral tunnel. Arthrosc Tech 10:e151–e158

Lysholm J, Gillquist J (1982) Evaluation of knee ligament surgery results with special emphasis on use of a scoring scale. Am J Sports Med 10:150–154

Majewski M, Stoll R, Widmer H, Muller W, Friederich NF (2006) Midterm and long-term results after arthroscopic suture repair of isolated, longitudinal, vertical meniscal tears in stable knees. Am J Sports Med 34:1072–1076

Marinescu R, Laptoiu D, Negrusoiu M (2003) Outside-in meniscus suture technique: 5 years’ follow-up. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 11:167–172

Migliorini F, Cuozzo F, Cipollaro L, Oliva F, Hildebrand F, Maffulli N (2022) Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) augmentation does not result in more favourable outcomes in arthroscopic meniscal repair: a meta-analysis. J Orthop Traumatol 23:8

Migliorini F, Oliva F, Eschweiler J, Cuozzo F, Hildebrand F, Maffulli N (2023) No evidence in support of arthroscopic partial meniscectomy in adults with degenerative and nonobstructive meniscal symptoms: a level I evidence-based systematic review. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 31:1733–1743

Migliorini F, Vecchio G, Giorgino R, Eschweiler J, Hildebrand F, Maffulli N (2023) Micro RNA in meniscal ailments: current concepts. Br Med Bull 145:141–150

Mostafaee N, Negahban H, Shaterzadeh Yazdi MJ, Goharpey S, Mehravar M, Pirayeh N (2020) Responsiveness of a persian version of knee injury and osteoarthritis outcome score and tegner activity scale in athletes with anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction following physiotherapy treatment. Physiother Theory Pract 36:1019–1026

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD et al (2021) The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372:n71

Persson F, Turkiewicz A, Bergkvist D, Neuman P, Englund M (2018) The risk of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis after arthroscopic meniscus repair vs partial meniscectomy vs the general population. Osteoarthr Cartil 26:195–201

Petersen W, Karpinski K, Bierke S, Muller Rath R, Haner M (2022) A systematic review about long-term results after meniscus repair. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 142:835–844

Pogorelic Z, Puizina E, Jukic M, Mestrovic J, Pintaric I, Furlan D (2020) Arthroscopic management of meniscal injuries in adolescents: outside-in suturing versus meniscal dart technique. Acta Clin Croat 59:431–438

Raoulis V Sr, Fyllos A, Baltas C, Schuster P, Bakagiannis G, Zibis AH et al (2021) Clinical and radiological outcomes after isolated anterior horn repair of medial and lateral meniscus at 24 months’ Follow-up, With the Outside-in Technique. Cureus 13:e17917

Ro KH, Kim JH, Heo JW, Lee DH (2020) Clinical and radiological outcomes of meniscal repair versus partial meniscectomy for medial meniscus root tears: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Orthop J Sports Med 8:2325967120962078

Rocha de Faria JL, Pavao DM, Padua VBC, Sousa EB, Guimaraes JM, Gomes BA et al (2020) Outside-in continuous meniscal suture technique of the knee. Arthrosc Tech 9:e1547–e1552

Sherman SL, DiPaolo ZJ, Ray TE, Sachs BM, Oladeji LO (2020) Meniscus injuries: a review of rehabilitation and return to play. Clin Sports Med 39:165–183

Solomon AJ, Arrambide G, Brownlee W, Cross AH, Gaitan MI, Lublin FD et al (2022) Confirming a historical diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: challenges and recommendations. Neurol Clin Pract 12:263–269

Tian B, Zhang M, Kang X (2023) Strategies to promote tendon-bone healing after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: present and future. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 11:1104214

Turcotte JJ, Maley AD, Levermore SB, Petre BM, Redziniak DE (2021) Risk factors for all-inside meniscal repair failure in isolation and in conjunction with anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee 28:9–16

Twomey-Kozak J, Jayasuriya CT (2020) Meniscus repair and regeneration: a systematic review from a basic and translational science perspective. Clin Sports Med 39:125–163

van der Lelij TJN, Gerritsen LM, van Arkel ERA, Munnik-Hagewoud R, Zuurmond RG, Keereweer S et al (2022) The role of patient characteristics and the effects of angiogenic therapies on the microvasculature of the meniscus: a systematic review. Knee 38:91–106

van Trommel MF, Simonian PT, Potter HG, Wickiewicz TL (1998) Arthroscopic meniscal repair with fibrin clot of complete radial tears of the lateral meniscus in the avascular zone. Arthroscopy 14:360–365

Vint H, Quartley M, Robinson JR (2021) All-inside versus inside-out meniscal repair: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Knee 28:326–337

Vinyard TR, Wolf BR (2012) Meniscal repair: outside-in repair. Clin Sports Med 31:33–48

Wang L, Zhang K, Liu X, Liu Z, Yi Q, Jiang J et al (2021) The efficacy of meniscus posterior root tears repair: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 29:23094990211003350

Warren RF (1985) Arthroscopic meniscus repair. Arthroscopy 1:170–172

Wells ME, Scanaliato JP, Dunn JC, Garcia EJ (2021) Meniscal injuries: mechanism and classification. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev 29:154–157

Wiley TJ, Lemme NJ, Marcaccio S, Bokshan S, Fadale PD, Edgar C et al (2020) Return to play following meniscal repair. Clin Sports Med 39:185–196

Xu C, Zhao J (2015) A meta-analysis comparing meniscal repair with meniscectomy in the treatment of meniscal tears: the more meniscus, the better outcome? Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 23:164–170

Zhuo H, Chen Q, Zhu F, Li J (2020) Arthroscopic side-to-side repair for complete radial posterior lateral meniscus root tears. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 21:130

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. No external source of funding was used.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FM conception, statistical analyses, writing; NM was involved in the supervision, revision, final approval; MP assisted in the literature search, data extraction, methodological quality assessment; CK: writing; MC: contributed to the literature search, data extraction, methodological quality assessment; AB contributed to the supervision. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Migliorini, F., Pilone, M., Bell, A. et al. Outside-in repair technique is effective in traumatic tears of the meniscus in active adults: a systematic review. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 31, 4257–4264 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-023-07475-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-023-07475-z