Abstract

The deposition of excess fine sediment and clogging of benthic substrates is recognised as a global threat to ecosystem functioning and community dynamics. Legacy effects of previous sedimentation create a habitat template on which subsequent ecological responses occur, and therefore, may have a long-lasting influence on community structure. Our experimental study examined the effects of streambed colmation (representing a legacy effect of fine sediment deposition) and a suspended fine sediment pulse on macroinvertebrate drift and community dynamics. We used 12 outdoor stream mesocosms that were split into two sections of 6.2 m in length (24 mesocosm sections in total). Each mesocosm section contained a coarse bed substrate with clear bed interstices or a fine bed substrate representing a colmated streambed. After 69 days, a fine sediment pulse with three differing fine sediment treatments was applied to the stream mesocosms. Added fine sediment influenced macroinvertebrate movements by lowering benthic density and taxonomic richness and increasing drift density, taxonomic richness, and altering drift assemblages. Our study found the highest dose of sediment addition (an estimated suspended sediment concentration of 1112 mg l−1) caused significant differences in benthic and drift community metrics and drift assemblages compared with the control treatment (30 l of water, no added sediment). Our results indicate a rapid response in drifting macroinvertebrates after stressor application, where ecological impairment varies with the concentration of suspended sediment. Contrary to expectations, bed substrate characteristics had no effect on macroinvertebrate behavioural responses to the fine sediment pulse.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

At a global scale, many freshwater ecosystems experience increased fine sediment loadings that impact their ecological functioning and biodiversity (Ormerod et al. 2010). Fine sediments (generally defined as inorganic and organic particles < 2 mm in size: Wood and Armitage 1997; Jones et al. 2012) can infiltrate into bed substrates and cause streambed colmation/clogging (Mathers et al. 2017a; Wilkes et al. 2019; McKenzie et al. 2020), which can alter macroinvertebrate community structure and functioning (Jones et al. 2012; Descloux et al. 2013; Wood et al. 2016; Mathers et al. 2017b). The ecological impacts of fine sediment on macroinvertebrates depends on the magnitude, frequency and duration of fine sediment supply and transport (Evans and Wilcox 2014). In addition, previous abiotic and biotic legacies influence the habitat template on which subsequent ecological responses occur (Parsons et al. 2006). Therefore, colmation may have a long-lasting influence on macroinvertebrate communities and effect their responses to future disturbances. Identifying the legacy effects of colmation and other stresses on river ecosystems is important for water managers and conservation efforts in order to understand the responses of macroinvertebrate communities to future disturbances.

High loads of suspended particles and deposited fine sediment have a complex mix of direct (physical and chemical) and indirect effects on macroinvertebrate communities (Sear et al. 2008; Jones et al. 2012; Wharton et al. 2017). Suspended fine sediment and saltating particles can physically dislodge periphyton and macroinvertebrates from the substrate by abrasion (Bilotta and Brazier 2008; Neale et al. 2008), and cause damage to fleshy body parts and gills in macroinvertebrates (Jones et al. 2012; Wharton et al. 2017). Increased turbidity reduces available light for primary producers and visual predators (Rowe and Dean 1998; Parkhill and Gulliver 2002) and alters the feeding efficiency of filter-feeders and grazers (Broekenhuizen et al. 2001). Successive pulses of fine particles in gravel-bedded rivers can infill void spaces in bed substrates and modify particle size composition (Evans and Wilcox 2014). Thus, historical fine sediment pulses (i.e. legacy effects) may influence the ecological responses of macroinvertebrates to future sediment disturbances. Previous studies have examined invertebrate community responses to suspended fine sediment additions (e.g. Gibbins et al. 2007a; Larsen and Ormerod 2010; Béjar et al. 2017), but less research has incorporated the legacy effects of previous fine sediment pulses on the response of macroinvertebrates to future sediment disturbances.

Colmated streambeds can cause changes to benthic macroinvertebrate community structure and functioning (Growns et al. 2017; Mathers et al. 2017b, 2019; Beermam et al. 2018; Blöcher et al. 2020). Previous studies have demonstrated declines in benthic diversity and density, and changes in assemblage composition with increased deposited fine sediment (Lenat et al. 1979; Waters 1995). Invertebrates tolerant of low dissolved oxygen concentrations and taxa capable of burrowing into the substrate tend to dominate colmated streambeds (Angradi 1999; Zweig and Rabeni 2001; Rabeni et al. 2005). Furthermore, taxa that are vulnerable to damage of filter-feeding apparatus or gills tend to be absent from colmated streambeds (Wood and Armitage 1997; Larsen et al. 2009). The proportion of Ephemeroptera, Plecoptera and Trichoptera (EPT) typically declines with increases in suspended and deposited fine sediment (Bjornn et al. 1977; Lenat et al. 1979), whilst other taxa, such as Oligochaeta, show the opposite pattern (Angradi 1999; Zweig and Rabeni 2001; Gayraud et al. 2002). These changes in benthic assemblages are partly due to habitat homogenisation, and reductions in porosity and interstitial habitat (Descloux et al. 2013). In colmated sediments, reduced porosity and permeability influence the volume of interstitial space for invertebrates and the size of movement pathways between grains (Stubbington 2012). Coarse-grained frameworks allow bidirectional migration of macroinvertebrates between the benthic and the hyporheic zone, but colmation can limit or prohibit vertical movement, leading to changes in the hyporheic community (Jones et al. 2015). Yet, there is an absence of research examining the behavioural response of macroinvertebrates to pulse disturbances when vertical migration pathways are disrupted.

Key invertebrate behavioural responses to suspended and deposited fine sediment, and other stresses include drift (i.e. the active or passive downstream movement of organisms; Bilton et al. 2001), vertical migration to the hyporheic zone (e.g. the hyporheic refuge hypothesis; Palmer et al. 1992), and aerial colonisation (Heino 2013). Less common dispersal mechanisms include upstream migration by some rheophilic taxa (Bruno et al. 2012), and lateral movements to floodplain habitats by crawling, flying or swimming (Turner 1993). Invertebrate drift may reflect an individual’s decision to maximise foraging opportunities (Hildebrand 1974; Kohler 1985) and to avoid predators and other unfavourable abiotic conditions (both natural behavioural decisions; Gibbins et al. 2007b; James et al. 2009; Larsen and Ormerod 2010). Periodicity of drift density is typically crepuscular with peaks at dawn/dusk (Neale et al. 2008) and seasonal peaks linked with emergence behaviour (Townsend 1980; Cellot 1989; Sagar and Glova 1992). The density of drifting invertebrates generally increases with high-velocity flow conditions and suspended fine sediment loads (Culp et al. 1986; Doeg and Milledge 1991; Suren et al. 2005; Larsen and Ormerod 2010). Substantial drift can modify benthic community composition, but dispersal abilities and propensity to drift vary between taxa. Bivalves and gastropods are sedentary, less motile and depend on drifting to colonise new habitats, whereas more motile taxa, such as trichopterans and plecopterans also crawl and swim (Mackay 1992). Abundant taxa in the drift include baetid and leptophlebiid mayflies, Gammarus (Gammaridae), and simuliid and chironomid fly larvae (Giller and Malmqvist 2003). Caddis fly larvae from the families Hydropsychidae and Polycentropodidae are also common drifters, whereas heptageniid mayflies, planarians, cased caddis, and molluscs are rarer in the drift (Giller and Malmqvist 2003). Nevertheless, the extent to which macroinvertebrates use drift to avoid unfavourable conditions depends on what other avoidance strategies are possible. Few studies have examined how bed substrate characteristics impact the propensity of macroinvertebrates to drift during a suspended fine sediment pulse.

This study addresses the individual and interactive effects of a suspended fine sediment pulse and streambed colmation on macroinvertebrate community response using outdoor stream mesocosms. Outdoor flow-through channels or stream mesocosms that are naturally fed by river water and colonised by invertebrates are useful to reproduce natural conditions and examine the effects of stressors on macroinvertebrate communities (Connolly and Pearson 2007), whilst allowing users to reduce confounding factors present in field settings (O’Hop and Wallace 1983). This study aimed to identify the effect of differing doses of suspended fine sediment on the propensity of invertebrates to drift whilst accounting for the legacy effects of previous streambed colmation. The following hypotheses were tested:

-

1.

Suspended fine sediment additions will lower benthic and increase drift density, taxonomic richness, and modify benthic and drift assemblages.

-

2.

Differences in bed substrate (i.e. coarse and fine) will influence benthic and drift invertebrate structure (i.e. densities, taxonomic richness and assemblages) before and during the fine sediment pulse. We predict a higher density of invertebrates drifting from the fine compared with the coarse bed substrate, but with differing drift responses between taxa.

Colmated streambeds are characterised by fine particles and small pores restrict large individuals and limit vertical migration into the hyporheic zone (Gayraud and Philippe 2001; Descloux et al. 2013; Vadher et al. 2015; Mathers et al. 2019). If individuals are unable to access subsurface sediments, there may be increased invertebrate drift from a colmated streambed in response to suspended fine sediment pulses due to limited interstitial space.

Materials and methods

Study site

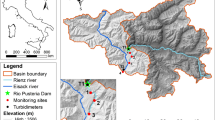

Twelve outdoor flow-through stream mesocosms were used for the experiment at the River Laboratory in Dorset, in the UK (Fig. 1). The stream mesocosms are fed by the Mill Stream, which is a branch of the River Frome. The River Frome is a lowland meandering river (8.1–264.6 mAOD) and is dominated by pool-riffle-glide morphology (National River Flow Archive [NRFA] 2020). The catchment area is 414 km2 and the land-use is predominantly agriculture/horticulture (47.3%) and grassland (37.5%), with other minor land-uses of woodland (9.4%), urban sites (3.6%) and heathland/bog (1.3%; NFRA 2020). The Frome flows through Jurassic limestones, mudstones and cretaceous upper greensand in the headwaters, cretaceous chalk bedrock in the upper and middle reaches, and mixed tertiary geology including sands, gravels and clays in the lower reaches (Collins and Walling 2007; Environment Agency 2012). Mean annual discharge was 6.662 m3 s−1 and the baseflow index was 0.86 during 1965–2018 at East Stoke gauging station, which is located at the study site (NRFA 2020).

Experimental design and procedure

The experiment ran between June and September 2015 using 12 flow-through stream mesocosms. The mesocosms were arranged in four blocks containing three steel linear stream mesocosms, situated at ~ 140° to the Mill Stream. Each mesocosm was 0.33 m in width, 12.4 m in length and 0.30 m in depth, and the distance between each block was 2.5 m. We split each stream mesocosm into two 6.2 m sections to provide 24 mesocosm sections.

Sediment for the coarse and the fine bed substrate was obtained from a local quarry who sourced the sediment from a gravel pit on the River Frome floodplain. The coarse bed substrate comprised sand (< 2 mm, 6.6%), gravel (10 mm, 13.3%), pebble (20 mm, 66.6%) and cobbles (> 64 mm, 13.3%), whereas the fine bed substrate contained sand (25%), gravel (37.5%) and pebble (37.5%). The sediment proportions were selected to reflect the particle range found in chalk streams (Armitage 1995; Ledger et al. 2009). The coarse bed substrate had clear bed interstices and represented a reach with relatively little fine sediment deposition. The fine bed substrate was used to represent a colmated streambed that had experienced high fine sediment deposition and lacked interstitial space. We filled each mesocosm section to a depth of 20 cm with either coarse or fine dry substrate, which provided 12 coarse and 12 fine mesocosm sections (Fig. 2).

Water from the Mill Stream was diverted through each block of mesocosms on 9 June 2015 (day 1). Average current velocity in the mesocosms was 0.11 ms−1 ± 0.01 (mean ± SE; n = 24) and average water depth was 5.16 ± 0.18 cm (n = 24; measured once on day 99). Mesocosms were left for 69 days for natural colonization by drifting invertebrates and algae from the Mill Stream (Jones et al. 2015). Natural colonization in each mesocosm was supplemented by adding invertebrates from four 3 min kick samples collected from the Mill Stream. Benthic macroinvertebrates were sampled from four riffles that possessed a coarse-grained structure with no fine sediment infiltration. Equal aliquots were added directly to the head of each mesocosm. During the colonization phase, shade cloths covered the mesocosms to reduce the development of diatom mats that may have encouraged fine sediment deposition (Jones et al. 2014).

Sediment for the suspended fine sediment treatments was obtained from deposited material in nearby reaches of the River Frome. The sediment was frozen for 48 h to eliminate any invertebrates and sieved using a 2 mm mesh to remove any coarse particles. This sediment was mixed with water from the Mill Stream to produce three suspended fine sediment treatments: (1) no sediment (30 l of water), (2) a moderate suspended fine sediment input (a suspension of 15 kg sediment in 30 l of water = 0.5 kg l−1), and (3) a concentrated slurry of fine suspended (i.e. a high treatment of 30 kg sediment in 30 l of water = 1 kg l−1). Over a 4-h period, we calculate the medium and high suspended fine sediment treatment would give suspended sediment concentrations of 556 mg l−1 and 1112 mg l−1 (based on average velocity and depth values). The suspended fine sediment treatments were added at the head of each of the 24 mesocosm section in a crossed design with the bed substrate types (Fig. 2).

Prior to the addition of the suspended fine sediment treatments, a 5-l sample of substrate was taken randomly from the coarse and the fine bed substrate to ensure consistency within the bed sediment types between the mesocosm sections, and to confirm differences between the coarse and the fine bed sediment upon installation. The substrate in each sample was oven dried at 60 °C and sieved into the following size fractions: < 0.125, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 31.5, 45 and 63 mm or greater. Each size fraction was weighed to determine the particle size distribution within each substrate sample.

Macroinvertebrate sampling

Drifting invertebrates were collected using drifts nets (0.4 × 0.25 m; 1 mm mesh size) that were positioned at the end of each mesocosm section (at 6.2 m and at 12.4 m) to intercept all the flow and thus, to reduce any influence of spatial variation (Neale et al. 2008). The drift nets spanned the width of the mesocosms (i.e. 0.33 m). Each mesocosm section was treated as a separate, independent experimental unit. Drift samples were collected before, during, immediately after (24 h after suspended fine sediment input) and 30 days after the suspended fine sediment pulse. On each sampling occasion, drift nets were deployed for 24 h and invertebrates were collected every 6 h (i.e. providing four 6-h drift samples for each sampling period) to accommodate the crepuscular nature of macroinvertebrate drift. The experimental set-up comprised 24 mesocosm sections × four 6-h drift samples × 4 sampling occasions, which provided 384 drift samples.

Benthic invertebrates were sampled from each mesocosm section on the day before, immediately after (24 h after suspended sediment input) and 30 days after suspended fine sediment addition. A benthic sample was taken at a random upstream and downstream location within each mesocosm section using a Surber sampler (0.2 m2, 250 μm mesh net) where the bed substrate was disturbed using a metal rod for two minutes. In total, 144 benthic samples were collected (i.e. 2 benthic invertebrate samples × 24 mesocosms × 3 sampling occasions). All benthic and drift invertebrate samples were sieved through a 250 μm mesh and were preserved in the field using 99% industrial methylated spirits. Invertebrates were identified to the lowest taxonomic level possible, in many cases to species, although, Oligochaeta and Hydracarina were identified at the class level.

Statistical analysis

Variation in bed sediment particle size and the percentage of fine particles between the colmated and the clean bed at the start of the experiment were examined using a one-way Analysis of Similarity (ANOSIM) and visualised using a cumulative frequency graph. A square root transformation was applied to the particle size data to decrease any effects of skewed distributions before the ANOSIM analyses and Euclidean distance was used as a dissimilarity measure (Clarke and Gorley 2006).

Before statistical analysis, macroinvertebrate data was log10 (x + 1) transformed to normalise residuals. Differences in benthic and drift density (the number of drifting invertebrates per 100 m−3) and taxonomic richness to suspended fine sediment additions and bed substrate conditions were tested by linear mixed effects models (LMMs) using the lme function from the package nlme (Pinheiro et al. 2018). Bed substrate type, time, and suspended fine sediment treatment were included as fixed interacting factors and block was specified as a random factor to account for any potential positional effect caused by the mesoscosms. All LMMs were fitted using the restricted maximum likelihood (REML) estimation function. Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) tests were used for all pairwise differences (i.e., for bed substrate, time and suspended fine sediment treatments) to decrease the probability of a Type I error. These tests were undertaken using the glht function in the multcomp package (Hothorn et al. 2008).

First, LMMs identified any effect of bed substrate on benthic and drift community metrics before suspended fine sediment was added. Bed substrate was fitted as a fixed interacting factor and block as a random effect. This LMM aimed to examine the effect of bed substrate on the four-community metrics before stressor application. Further LMMs identified the individual and interactive effects of suspended fine sediment treatment, bed substrate and time (all fixed factors with block as a random factor) on benthic and drift community structure (i.e. the four-community metrics). Lastly, LMMs determined any differences in drift community structure with varying suspended fine sediment treatments during and after the fine sediment pulse. This analysis aimed to test if the fine sediment pulse caused an immediate or a delayed response in drift. All univariate analyses were carried out using R, version 3.6.3 (R Development Core Team 2015).

Permutational Multivariate Analysis of Variance (PERMANOVA) models were used to determine any differences in benthic and drift assemblages caused by the main factors and their interactions. Similar to the univariate analysis, a PERMANOVA model examined the influence of bed substrate on benthic and drift assemblages before the fine sediment pulse. A further PERMANOVA determined the effect of time and suspended fine sediment treatments on drift assemblage. Bed substrate, time, and suspended fine sediment treatments were fitted as fixed factors and block was a random factor in both PERMANOVA models. Similarity percentage analysis (SIMPER) was conducted to determine which species were driving differences in assemblages between the main factors, and Non-metric Multidimensional Scaling (NMDS) ordination plots were used to visualise compositional patterns. Bray–Curtis similarity coefficients were used for all multivariate analyses (i.e., all PERMANOVA models, SIMPERs and NMDS ordination plots) on the invertebrate data set. All multivariate analyses, including the particle size data were performed using PRIMER V7 and the PERMANOVA + add-on (PRIMER-E Ltd, Plymouth, UK; Clarke and Gorley 2006; Anderson et al. 2008).

Results

Bed sediments

Before the suspended fine sediment pulse, there was a significant difference in the size of bed sediment particles between the coarse and the fine bed substrate (ANOSIM; r = 0.907, p < 0.001; Fig. 3). The colmated bed contained a higher percentage of fine particles (18%) compared with the coarse bed (3.89%; ANOSIM; r = 0.655, p = 0.001). D50 was 8.79 mm in the colmated bed and 16.51 mm in the clean bed. The ANOSIM analysis was visually supported by a cumulative frequency plot that shows distinct particle size distributions between the fine and the coarse bed (Fig. 3).

Influence of colmation on benthic and drift metrics and invertebrate assemblages

Tanypodinae and Tanytarsini (both dipterans: Chironomidae) dominated the benthic community, accounting for 27.7 and 27.4% of the total benthic invertebrate abundance. Ten other taxa comprised 1–9% of the benthic community: Oligochaeta (8.8%), Asellus aquaticus (Asellidae; 7.8%), Baetidae (5.1%), Gammarus pulex (Gammaridae; 4.4%), Hydropsyche pellucidula (Hydropsychidae; 4.2%), Hydroptila spp. (Hydroptilidae; 2.2%), Radix balthica (Lymnaeidae; 2.1%), Chironomini (1.9%), Ostracoda (1.2%), and Ephemera danica (Ephemeridae; 1.1%). These 12 taxa accounted for 93.9% of the benthic community with another 38 taxa constituting the remaining benthic invertebrate abundance.

The drift assemblage was characterised by R. balthica (19% of total abundance), G. pulex (15.4%) and baetids (11%). A total of 14 other taxa comprised 1–7% of the drift assemblage: Limnius volckmari (Elmidae; 6.4%), Brachycentrus subnubilus (Brachycentridae; 6.1%), H. pellucidula (5.3%), Tanytarsini (5.2%), Hydroptila spp. (3.8%), Tanypodinae (3.5%), A. aquaticus (3.4%), Crangonyx pseudogracilis (Crangonyctidae; 3%), Hydrophilidae (1.6%), Hydropsyche contubernalis (Hydropsychidae 1.4%), Corixidae (1.2%), Psychodidae (1.1%), Simuliidae (1.1%) and Elmis aenea (Elmidae; 1%). These 17 taxa contributed 89.7% of the drift assemblage whilst a further 45 taxa accounted for < 1%.

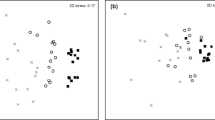

Before the suspended fine sediment additions, LMMs showed no difference in benthic density and taxonomic richness between the fine and the coarse bed (Table 1). Similarly, there were no difference in drift density and taxonomic richness between bed substrates (Table 1). Baetis rhodani, B. subnubilus and G. pulex were the most abundant taxa drifting from the coarse bed. Similarly, B. subnubilus, B. rhodani and R. balthica occurred in high densities from the colmated bed. Streambed colmation had no effect on the benthic (PERMANOVA; F value = 2.33, p > 0.05) or the drift assemblage (PERMANOVA; F value = 1.21, p > 0.05) prior to the suspended fine sediment pulse (Fig. 4).

Effect of suspended fine sediment additions and substrate on benthic and drift structure

Benthic density and taxonomic richness differed with time but did not vary with suspended fine sediment treatment or bed substrate (Table 2). Both benthic community metrics indicated a significant difference before and immediately after the suspended fine sediment pulse (LMMs; both p values < 0.001). Benthic densities increased from immediately after to 30 days post the fine sediment pulse (LMM; F value − 2.59, p value < 0.05). None of the two-way or three-way interactions were significant for any of the benthic community metrics (Table 2).

Drift density and drift varied with time and suspended fine sediment treatment (Table 2). Post-hoc tests revealed drift density and drift taxonomic richness significantly differed between sampling occasions. Both drift community metrics differed before and 30 days after suspended fine sediment addition, during and 30 days after suspended fine sediment addition, and between 1 and 30 days after suspended fine sediment addition (Supporting Information Table S1). Differences in both community metrics also existed between suspended fine sediment treatments. Post-hoc tests showed significantly higher drift density and higher drift taxonomic richness from the high suspended fine sediment treatment compared with the control, but no significant difference in community metrics were detected between the moderate and the high suspended fine sediment treatments (Table 1 and Supporting Information Table S2). Furthermore, no differences in drift density or drift taxonomic richness existed between bed substrates, indicating no effect of the colmated bed. LMMs also indicated no interactive effects between any of the main factors (all p values > 0.05; Table 1).

Drift assemblage (PERMANOVA; F = 6.52, p < 0.001) differed significantly with time (Table 3 and Fig. 5a). Planned contrasts revealed drift assemblages differed significantly between all time periods (Table 3). The drift assemblages of the different time periods were widely dispersed and overlapping, indicating high community heterogeneity within groups, but were still significantly different from one another (Fig. 5a). The top five taxa characterising the time period before suspended fine sediment addition were B. rhodani (26.3% contribution to the dissimilarity), R. balthica (17.9%), B. subnubilus (14%), G. pulex (12.6%) and Tanypodinae (6.2%). These five taxa accounted for 77% of the drift assemblage. During the fine sediment pulse, L. volckmari (27.6%), G. pulex (23.1%), B. rhodani (13.1%), R. balthica (8.1%) and H. pellucidula (5.8%) dominated the drift assemblage (accounting for 77.6% of the composition). 24 h after the suspended fine sediment pulse, three of the five taxa continued to characterise the assemblage: R. balthica (34.2%), G. pulex (24.4%), and Baetidae (9.5%) with C. pseudogracilis and Tanypodinae contributing smaller abundances (5.8% and 4.9% respectively). These five taxa cumulatively accounted for 78.7% of the assemblage. Post 30 days, the drift assemblage continued to comprise high abundances of R. balthica (25%) and G. pulex (18%). H. pellucidula (8.4%), B. rhodani (7.3%) and Hydroptila spp. (6.2%) contributed smaller abundances (cumulatively the five taxa accounted for 64.8% of the drift assemblage). Although many taxa occurred in most time periods, variation in abundances of these taxa contributed to significant differences in drift assemblage between sampling occasions.

The different concentrations of suspended fine sediment added also impacted macroinvertebrate drift assemblages (PERMANOVA; F = 1.65, p < 0.05). A significant difference was evident between the drift assemblages that experienced no added fine sediment (i.e. the control) and the high suspended fine sediment treatment (Table 2; Fig. 5b). Macroinvertebrate taxa causing compositional differences between sediment treatments were G. pulex (contributing 8.8% to the dissimilarity), B. rhodani (8.4%), R. balthica (7.8%), L. volckmari (6%) and B. subnubilus (5.5%), which all occurred in higher abundances in the high suspended fine sediment treatment. Bed substrate did not influence drift assemblages and none of the interactions between the main factors were significant (Table 3; Fig. 5c).

Influence of suspended fine sediment treatment on drift structure during and immediately after the fine sediment pulse

Drift macroinvertebrate density and drift taxonomic richness were greater in the high suspended fine sediment treatment than the control during the suspended fine sediment pulse (Table 4). Drift densities and taxonomic richness were also greater in the high compared to the moderate suspended fine sediment treatment. Differences in both drift community metrics changed rapidly with time after the fine sediment pulse. No differences occurred in any of the drift community metrics 24 h after the disturbance event (Table 4).

Crepuscular drift

An increase in drift density occurred immediately after the high suspended fine sediment treatment was added, but drift density from the control and moderate suspended fine sediment treatment initially remained comparable to pre-disturbance densities (Fig. 6). In all three suspended fine sediment treatments, drift densities increased significantly during the first evening and night after the fine sediment pulse (sampling period 17:50–23:50 and 23:50–5:50 h). A second, smaller peak in invertebrate drift occurred the second night after sediment input in mesocosms that experienced the moderate and high suspended fine sediment treatment (sampling period 21:00–3:00 and 3:00–9:00 h). However, drift densities from the control were noticeably lower compared with the other sediment treatments and exhibited no distinct second night peak.

Discussion

Effects of increased suspended fine sediment

Our first hypothesis that increases in suspended fine sediment will lower the density and taxonomic richness of the benthos, cause greater drift rates, and alter the composition of the drift assemblage was supported. Invertebrates typically leave the bed in increasing numbers as suspended fine sediment increases (e.g. Ciborowski et al. 1977). Key mechanisms suggested for increased drift include abrasion and clogging of gills and filter-feeding apparatus (Allan 2004; Jones et al. 2012). Abrasion by fine material can dislodge invertebrates from the bed (i.e. passive drift), but individuals may also actively release from the bed as a behavioural response to escape higher suspended sediment loads (i.e. active drift; Jones et al. 2012). Active drift may also occur in response to changes in bed composition caused by increased suspended sediment loads, i.e. an increase in fine sediment in the surface drape. Although many invertebrate species benefit from inputs of organic (food) particles associated with high fine sediment inputs, problems occur when sediment accretion exceeds the ability of invertebrates to excavate themselves (Wood et al. 2005). Increases in drift density may also be a behavioural response to the threat of burial (Béjar et al. 2017). Invertebrates may also enter the drift to avoid altered habitat conditions and decreased food quality and availability (Hildebrand 1974; Buendia et al. 2013a,b), a knock-on effect of bed composition changes. Our study demonstrated an initial increase in drift densities under the high fine sediment treatment, indicating either dislodgement or immediate avoidance behaviour to the fine sediment addition. However, most of the increase in invertebrate drift was delayed until after sunset (c. 21:00 h in summer) coinciding with a peak in drift in the control and moderate suspended fine sediment treatment (Fig. 6). This delayed response may reflect a behavioural reaction to changed benthic conditions after the suspended fine sediment pulse had passed or be a consequence of the crepuscular pattern of drifting (Tanaka 1960; Waters 1962; Muller 1963; Neale et al. 2008). Invertebrates actively drifting at night may also be deliberate to reduce predation risk from visually foraging, drift-feeding fishes (Allan 1978; Flecker 1992).

Previous studies examining interactions between suspended fine sediment transport, deposition and invertebrate drift dynamics have often focussed on short temporal scales (i.e. < 3 days; e.g. Gibbins et al. 2007b; Larsen and Ormerod 2010). A key feature of our study is the temporal scale as we monitored drift patterns 30 days after stressor application. Drift density was double and taxonomic richness increased 30 days after the suspended fine sediment addition, but there was no lasting effect of the experimental fine sediment pulse (i.e. no difference amongst treatments). Invertebrate drift often exhibits seasonal trends (Keeley and Grant 1997; Jenkins and Keeley 2010), but the direction and magnitude differs among studies (Naman et al. 2016). In temperate river networks, drift densities generally peak in summer and decrease in autumn, partly due to the life history characteristics of the drifting taxa (Fjellheim 1980; Cellot 1996; Giller and Malmqvist 2003), but spring (Hieber et al. 2003; Leeseberg and Keeley 2014) and autumn peaks (Stoneburner and Smock 1979) have also been reported. Neale et al. (2008) found higher densities of drifting invertebrates in summer (June and July) compared with spring (April and May) in a temperate chalk stream in the UK, but the study did not measure autumnal drift. In our study, we suggest increased drift rates after 30 days were likely due to seasonal and other factors, such as temperature, discharge, food resources, and the life history traits of drifting taxa rather than any legacy effects of increased sediment addition. This finding is important by highlighting the effects of suspended fine sediment inputs are short-lived, transient events, and with time, other abiotic and biotic factors are more influential in determining drift community structure.

Impact of suspended fine sediment treatment

Suspended fine sediment additions influenced drift rates and the taxonomic structure of the drift, which supports our first hypothesis. Drift assemblage structure differed between the control (i.e. no added fine sediment) and the high fine sediment treatment but did not differ between the moderate and the high suspended fine sediment treatments. There are numerous mechanisms that might account for increased drift rates during spates that tend to deliver fine sediments to rivers. Elevated discharges are generally accompanied with increases in near-bed shear stress, turbulence and the entrainment and transport of coarse and fine sediment (Vinson 2001; Bond and Downes 2003; Naman et al. 2017). Saltating particles and fine organic matter scour exposed benthic invertebrates (Gibbins et al. 2007a). If flows are sufficiently high, mobilisation of bed particles can occur and cause entrainment of surface and near-surface invertebrates (Anderson and Lehmkuhl 1968). In addition to increased near-bed shear stress and movement of bed particles, pulsed fine suspended sediment events are an additional pressure upon invertebrate communities. In our study, we did not increase flow substantially such that mobilisation of the bed would have occurred. Hence, the differences in drift between the sediment treatments (i.e. the control and the high fine sediment treatment) can be attributed to the effects of the fine sediment alone. This finding is important by revealing different mechanisms governing invertebrate drift, which is useful in developing effective conservation and management strategies.

Influence of substrate characteristics

Our second hypothesis that bed substrate characteristics will cause differences in benthic densities, drift rates and assemblage during increased suspended fine sediment was unsupported. Benthic and drift density, and taxonomic richness were similar from both bed substrates before, during and after the suspended fine sediment pulse. B. subnubilus and B. rhodani were the most common EPT taxa drifting from the colmated bed. Brachycentrus (Trichoptera) are filter feeders and use their forelimbs extended into the water to trap particles (Gallepp 1974), but switch to grazing when suspended sediment loads are high (Voelz and Ward 1992), possibly due to abrasion from particles or reduced quality of food (Jones et al. 2012). B. rhodani is a grazer and is intolerant of sediment deposition (Rabeni et al. 2005; Pollard and Yuan 2010), and drifts quickly as bedload transport rises (Gibbins et al. 2005). The higher drift densities from the colmated bed may reflect increased drift to avoid unfavourable patches or predators, and imply individuals have fewer escape routes in colmated sediments.

Past studies have found the hyporheic zone is an important invertebrate refuge that promotes community resilience during disturbances (Vander Voste et al. 2016). The effectiveness of the hyporheic zone as a refuge may be restricted by fine sediment reducing interstitial space and limiting vertical connectivity on invertebrates accessing lower sedimentary layers (Descloux et al. 2013; Vadher et al. 2015, 2017). We predicted a higher likelihood of invertebrates entering the drift from the fine compared with the coarse bed due to restricted interstitial space within colmated sediments. However, we found no interaction effects between colmation and the suspended fine sediment treatment on drift assemblages. Although physical dislodgement may be responsible for the initial increase in drift, as we detected a delayed response to the effects of the suspended fine sediment pulse in drift density, it is clear that at least part of the increase in drift is a driven by an active behavioural response from the macroinvertebrates. Hence, active use of the hyporheos to avoid the negative effects of a fine sediment pulse is possible: the influence of colmation on this avoidance mechanism could be tested by well-planned field, mesocosm and/or laboratory testing.

The advantages of mesocosms and spatial and temporal scales

Identifying the effects of multiple stresses on invertebrate responses to disturbances is complex (Beermann et al. 2018). Outdoor stream mesocosms are highly useful to determine the single and interactive effects of stresses if an appropriate set-up is used. A distinct advantage of using mesocosms that are fed by river water and colonised by invertebrates by drift or aerial oviposition is that the mesocosms have the same light, water temperature and chemistry as the feeder stream (Beerman et al. 2018). Furthermore, specific environmental conditions and stresses, such as bed composition and differing doses of sediment additions can be manipulated. Whilst using stream mesocosms to identify ecological responses to effects of stressors has many benefits, our mesocosms may only represent conditions from small streams. Rivers contain a mosaic of different physical habitats, including erosional and depositional patches, and a range of refugia that cannot be replicated within stream mesocosms (Larsen and Ormerod 2010). However, our findings are comparable with field surveys of greater spatial scales (e.g. Larsen and Ormerod 2010; Béjar et al. 2017) that have examined the impact of fine sediment on invertebrate communities.

Conclusion

This study shows the impacts of increased suspended fine sediment on benthic and drift structure. Drift structure (i.e. density and taxonomic richness) and assemblage composition were strongly influenced by the suspended fine sediment addition. Both drift structure and assemblage differed significantly between the control and the high fine sediment treatment. This finding demonstrates that the concentration of suspended fine sediment influences invertebrate behaviour. Invertebrates exhibited an immediate increase in drift and delayed avoidance behaviour where they drifted downstream after the fine sediment addition had finished. Despite assumptions that colmation of bed sediments would affect the drift response, as refuge in the hyporheos would be compromised, we found no difference in drift between the colmated and coarse sediments. Future research should evaluate the ecological impact of differing suspended fine sediments on invertebrate behaviour and examine multiple dispersal pathways simultaneously. Understanding the impacts and interactions of deposited and suspended fine sediment on macroinvertebrate behaviour is important for water management strategies to deploy effective conservation measures and address activities which result in increased fine sediment loading to river ecosystems.

References

Allan JD (1978) Trout predation and the size composition of stream drift. Limnol Oceanogr 23(6):1231–1237. https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.1978.23.6.1231

Allan JD (2004) Landscapes and riverscapes: the influence of land use on stream ecosystems. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst 35:257–284

Anderson NH, Lehmkuhl DM (1968) Catastrophic drift of insects in a woodland stream. Ecology 49(2):198–206. https://doi.org/10.2307/1934448

Anderson MJ, Gorley RN, Clarke KR et al (2008) PERMANOVA + for PRIMER: guide to software and statistical methods. PRIMER-E, Plymouth

Angradi TR (1999) Fine sediment and macroinvertebrate assemblages in Appalachian streams: a field experiment with biomonitoring applications. J N Am Benthol Soc 18:49–66

Armitage PD (1995) Faunal community change in response to flow manipulation. In: Harper D, Ferguson A (eds) The ecological basis for river management. Wiley, Chichester, pp 59–78

Beerman AJ, Elbrecht V, Karnatz S, Ma L, Matthaei CD, Piggott JJ, Leese F (2018) Multiple-stressor effects on stream macroinvertebrate communities: a mesocosm experiments manipulating salinity, FS and flow velocity. Sci Total Environ 610–611:961–971

Béjar M, Gibbins CN, Vericat D, Batalla RJ (2017) Effects of suspended sediment transport on invertebrate drift. River Res Appl 33:1655–1666

Bilotta GS, Brazier RE (2008) Understanding the influence of suspended solids on water quality and aquatic biota. Water Res 42:2849–2861

Bilton DT, Freeland JR, Okamura B (2001) Dispersal in freshwater invertebrates. Annu Rev Ecol Syst 32(1):159–181. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.32.081501.114016

Bjornn TC, Brusven MA, Molnau MP, Milligan JH, Chacho E, Schaue C (1977) Transport of granitic sediment in streams and its effects on insects and fish. University of Idaho

Blöcher JR, Ward MR, Matthaei CD, Piggott JJ (2020) Multiple stressors and stream macroinvertebrate community dynamics: Interactions between fine sediment grain size and flow velocity. Sci Total Environ 717:137070. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.137070

Bond NR, Downes BJ (2003) The independent and interactive effects of fine sediment and flow on benthic invertebrate communities characteristic of small upland streams. Freshw Biol 48:455–465. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2427.2003.01016.x

Broekenhuizen N, Parkyn S, Miller D (2001) Fine sediment effects on feeding and growth in the invertebrate grazers Potamopyrgus antipodarum (Gastropoda, Hydrobiidae) and Deleatidium sp (Ephemeroptera, Leptophlebiidae). Hydrobiologia 457:125–132

Bruno MC, Bottazzi E, Rossetti G (2012) Downward, upstream or downstream? Assessment of meio- and macrofaunal colonization patterns in a gravel-bed stream using artificial substrates. Int J Limnol 48:371–381

Buendia C, Gibbins CN, Vericat D, Batalla RJ, Douglas A (2013a) Detecting the structural and functional impacts of fine sediment on stream invertebrates. Ecol Ind 25:184–196

Buendia C, Gibbins CN, Vericat D, Batalla RJ (2013b) Reach and catchment-scale influences on invertebrate assemblages in a river with naturally high fine sediment loads. Limnologica 43:362–370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.limno.2013.04.005

Cellot B (1989) Macroinvertebrate movements in a large European river. Freshw Biol 22:45–55

Cellot B (1996) Influence of side-arms on macroinvertebrate drift in the main channel of a large river. Freshw Biol 4:64–78

Ciborowski JJH, Pointing PJ, Corkum LD (1977) The effect of current velocity and sediment on the drift of the mayfly Ephemerella subvaria Mcdunnough. Freshw Biol 7:567–572. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2427.1977.tb01708

Clarke KR, Gorley RN (2006) PRIMER v6: user manual/tutorial. PRIMER E-Ltd, Plymouth

Collins AL, Walling DE (2007) Fine-grained bed sediment storage within the main channel systems of the Frome and Piddle catchments, Dorset, UK. Hydrol Process 21:1448–1459

Connolly NM, Pearson RG (2007) The effect of fine sedimentation on tropical stream macroinvertebrate assemblages: a comparison using flow through artificial stream channels and recirculating mesocosms. Hydrobiologia 592:423–438

Culp JM, Wrona FJ, Davies RW (1986) Response of stream benthos and drift to fine sediment deposition versus transport. Can J Zool 64:1345–1351. https://doi.org/10.1139/z86-200

Descloux S, Datry T, Marmonier P (2013) Benthic and hyporheic invertebrate assemblages along a gradient of increasing streambed colmation by FS. Aquat Sci 75(4):493–507

Doeg TJ, Milledge GA (1991) Effect of experimentally increasing concentration of suspended sediment on macro-invertebrate drift. Aust J Mar Freshw Res 42(5):519–526

Environment Agency (2012) Frome and piddle catchment flood management plan: managing flood risk. Environment Agency, Manley House

Evans E, Wilcox C (2014) Fine sediment infiltration dynamics in a gravel-bed river following a sediment pulse. River Res Appl 30:372–384

Fjellheim A (1980) Differences in drifting of larval stages of Ryacophila nubile (Trichoptera). Holarct Ecol 52:93–110

Flecker AS (1992) Fish predation and the evolution of invertebrate drift periodicity: evidence from neotropical streams. Ecology 73(2):438–448. https://doi.org/10.2307/1940751

Gallepp G (1974) Diel periodicity in behaviour of the caddisfly, Brachycentrus americanus (Banks). Freshw Biol 4:193–204

Gayraud S, Philippe M (2001) Does subsurface interstitial space influence general features and morphological traits of the benthic invertebrate community in streams? Arch Hydrobiol 151(4):667–686

Gayraud S, Herouin E, Philippe M (2002) Colmatage mine´ral du lit des cours d’eau: revue bibliographique des me´canismes et des conse´quences sur les habitats et les peuplements de macroinverte´bre´s. Bull Fr Peˆche Piscic 365(366):339–355

Gibbins CN, Scott E, Soulsby C, McEwan I (2005) The relationship between sediment mobilisation and the entry of Baetis mayflies into the water column in a laboratory flume. Hydrobiologia 533:115–122

Gibbins C, Vericat D, Batalla RJ, Gomez CM (2007a) Shaking and moving: low rates of sediment transport trigger mass drift of stream invertebrates. Can J Fish Aquat Sci 64(1):1–5. https://doi.org/10.1139/f06-181

Gibbins C, Vericat D, Batalla RJ (2007b) When is stream invertebrate drift catastrophic? The role of hydraulics and sediment transport in initiating drift during flood events. Freshw Biol 52(12):2369–2384. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2427.2007.01858.x

Giller PS, Malmqvist B (2003) The biology of streams and rivers. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Growns I, Murphy JF, Jones JI (2017) The effects of altered flow and bed sediment on macroinvertebrates in stream mesocosms. Mar Freshw Res 68(3):495–505

Heino J (2013) Environmental heterogeneity, dispersal mode, and co-occurrence in stream macroinvertebrates. Ecol Evol 3(2):344–355

Hieber M, Robinson CT, Uehlinger U (2003) Seasonal and diel patterns of invertebrate drift in different alpine stream types. Freshw Biol 48(6):1078–1092. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2427.2003.01073.x

Hildebrand SG (1974) The relation of drift to benthos density and food level in an artificial stream. Limnol Oceanogr 19(6):951–957. https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.1974.19.6.0951

Hothorn T, Bretz F, Westfall P (2008) Simultaneous inference in general parametric models. Biom J 50:346–363

James ABW, Dewson ZS, Death RG (2009) The influence of flow reduction on macroinvertebrate drift density and distance in three New Zealand streams. J N Am Benthol Soc 28(1):220–232. https://doi.org/10.1899/07-146.1

Jenkins AR, Keeley ER (2010) Bioenergetic assessment of habitat quality for stream-dwelling cutthroat trout (Oncorhynchus clarkii bouvieri) with implications for climate change and nutrient supplementation. Can J Fish Aquat Sci 67(2):371–385. https://doi.org/10.1139/F09-193

Jones JI, Murphy JF, Collins AL, Sear DA, Naden PS, Armitage PD (2012) The impact of FS on macroinvertebrates. River Res Appl 28:1055–1071. https://doi.org/10.1002/rra.1516

Jones JI, Duerdoth CP, Collins AL, Naden PS, Sear DA (2014) Interactions between diatoms and FS. Hydrol Process 28:1226–1237

Jones I, Growns I, Arnold A, McCall S, Bowes M (2015) The effects of increased flow and FS on hyporheic invertebrates and nutrients in stream mesocosms. Freshw Biol 60:813–826. https://doi.org/10.1111/fwb.12536

Keeley ER, Grant JWA (1997) Allometry of diet selectivity in juvenile Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar). Can J Fish Aquat Sci 54(8):1894–1902. https://doi.org/10.1139/f97-096

Kohler SL (1985) Identification of stream drift mechanisms: an experimental and observational approach. Ecology 66(6):1749–1761. https://doi.org/10.2307/2937371

Larsen S, Ormerod SJ (2010) Low-level effects of inert sediments on temperate stream invertebrates. Freshw Biol 55:476–486

Larsen S, Vaughan IP, Ormerod SJ (2009) Scale-dependent effects of fine sediments on temperate headwater invertebrates. Freshw Biol 54:203–219

Ledger ME, Harris RML, Armitage PD, Milner AM (2009) Realism of model ecosystems: an evaluation of physicochemistry and macroinvertebrate assemblages in artificial streams. Hydrobiologia 617:91–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10750-008-9530-X

Leeseberg CA, Keeley ER (2014) Prey size, prey abundance, and temperature as correlates of growth in stream populations of cutthroat trout. Environ Biol Fishes 97:599–614. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10641-014-0219-x

Lenat DR, Penrose DL, Eagleson KW (1979) Biological evaluation of non-point source pollutants in North Carolina streams and rivers: biological series no 102. North Carolina Department of Natural Resources and Community Development, Raleigh

Mackay RJ (1992) Colonization by lotic macroinvertebrates: a review of processes and patterns. Can J Fish Aquat Sci 49(3):617–628. https://doi.org/10.1139/f92-071

Mathers KL, Collins AL, England J, Brierley B, Rice SP (2017a) The FS conundrum; quantifying, mitigating and managing the issues. River Res Appl 33:1509–1514

Mathers KL, Rice SP, Wood PJ (2017b) Temporal effects of enhanced FS loading on macroinvertebrate community structure and functional traits. Sci Total Environ 599–600:513–522

Mathers KL, Hill MJ, Wood CD, Wood PJ (2019) The role of fine sediment characteristics and body size on the vertical movement of a freshwater amphipod. Freshw Biol 64:152–163

McKenzie M, Mathers KL, Wood PJ, England J, Foster I, Lawler D, Wilkes M (2020) Potential physical effects of suspended fine sediment on lotic macroinvertebrates. Hydrobiologia 847:697–711. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-019-04131-x

Muller K (1963) Diurnal rhythm in organic drift of Gammarus pulex. Nature 198:806–807

National River Flow Archive (2020) 44001—Frome at East Stoke Total. https://nrfa.ceh.ac.uk/data/station/info/44001. Accessed 25 Feb 2020

Naman SM, Rosenfeld JS, Richardson JS (2016) Causes and consequences of invertebrate drift in running waters: from individuals to populations and trophic fluxes. Can J Fish Aquat Sci 73:1292–1305. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjfas-2015-0363

Naman SM, Rosenfeld JS, Richardson JS, Way JL (2017) Species traits and channel architecture mediate flow disturbance impacts on invertebrate drift. Freshw Biol 62:340–355. https://doi.org/10.1111/fwb.12871

Neale MW, Dunbar MJ, Jones JI, Ibbotson AT (2008) A comparison of the relative contributions of temporal and spatial variation in the density of drifting invertebrates in a Dorset (U.K.) chalk stream. Freshw Biol 53:1513–1523

O’Hop J, Wallace JB (1983) Invertebrate drift, discharge, and sediment relations in a southern Appalachian headwater stream. Hydrobiologia 98:71–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00019252

Ormerod SJ, Dobson M, Hildrew AG, Townsend CR (2010) Multiple stressors in freshwater ecosystems. Freshw Biol 55(Suppl. 1):1–4

Palmer MA, Bely AE, Berg KE (1992) Response of invertebrates to lotic disturbance: a test of the hyporheic refuge hypothesis. Oecologia 89:182–194

Parkhill KL, Gulliver JS (2002) Effect of inorganic sediment on whole stream productivity. Hydrobiologia 472:5–17

Parsons M, McLoughlin CA, Rountree MW, Rogers KH (2006) The biotic and abiotic legacy of a large infrequenct flood disturbance in the Sabie River, South Africa. River Res Appl 22:187–201

Pinheiro J, Bates D, DebRoy S, Sarkar D, R Core Team (2018) nlme: Linear and nonlinear mixed effects models. R package version 3.1–137. Retrieved from: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=nlme. Accessed 13 July 2020

Pollard AI, Yuan LL (2010) Assessing the consistency of response metrics of the invertebrate benthos: a comparison of trait- and identity-based measures. Freshw Biol 55(7):1420–1429

R Development Core Team (2015) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/. Accessed 13 July 2020

Rabeni CF, Doisy KE, Zweig LD (2005) Stream invertebrate community functional responses to deposited sediment. Aquat Sci 67:395–402

Rowe D, Dean TL (1998) Effects of turbidity on the feeding ability of the juvenile migrant stage of six New Zealand freshwater fish species. N Z J Mar Freshw Res 32:21–29

Sagar PM, Glova GJ (1992) Invertebrate drift in a large, braided New Zealand river. Freshw Biol 27:405–416

Sear DA, Frostick LB, Rollinson G, Lisle TE (2008) The significance and mechanics of fine sediment infiltration and accumulation in gravel spawning beds. In: Sear DA, Devries P (eds) Salmonid spawning habitat in rivers; physical controls, biological responses and approaches to remediation. AFS, Bethesda, pp 149–174

Stoneburner DL, Smock LA (1979) Seasonal fluctuations of macroinvertebrate drift in a South Carolina Piedmont stream. Hydrobiologia 63(1):49–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00021016

Stubbington R (2012) The hyporheic zone as and invertebrate refuge: a review of variability in space, time, taxa and behaviour. Mar Freshw Res 63(4):293–311

Suren AM, Martin ML, Smith BJ (2005) Short-term effects of high suspended sediments on six common New Zealand stream invertebrates. Hydrobiologia 548:67–74

Tanaka H (1960) On the daily change of the drifting of benthic animals in stream, especially on the types of daily change observed in taxonomic groups of insects. Bull Freshw Fish Res Lab Tokyo 9:13–26

Townsend CR (1980) The ecology of streams and rivers. Edward Arnold Ltd, London

Turner C (1993) Episodic pollution and recovery in streams. Ph.D. thesis, Cardiff University

Vadher AN, Stubbington R, Wood PJ (2015) FS reduces vertical migrations of Gammarus pulex (Crustacea: Amphipoda) in response to surface water loss. Hydrobiologia 753:61–71

Vadher AN, Leigh C, Millett J, Stubbington R, Wood PJ (2017) Vertical movements through subsurface stream sediments by benthic macroinvertebrates during experimental drying are influenced by sediment characteristics and species traits. Freshw Biol 62:1730–1740. https://doi.org/10.1111/fwb.12983

Vander Vorste R, Malard F, Datry T (2016) Is drift the primary process promoting the resilience of river invertebrate communities? A manipulative field experiment in an intermittent alluvial river. Freshw Biol 61:1276–1292

Vinson MR (2001) Long-term dynamics of an invertebrate assemblage downstream of a large dam. Ecol Appl 11(3):711–730. https://doi.org/10.1890/1051-0761(2001)011[0711:LTDOAI]2.0.CO;2

Voelz NJ, Ward JV (1992) Feeding habits and food resources of filter feeding Trichoptera in a regulated mountain stream. Hydrobiologia 231:187–196

Waters TF (1962) Diurnal periodicity in the drift of stream invertebrates. Ecology 43:316–320

Waters TF (1995) Sediment in streams: sources, biological effects, and control: monograph 7. American Fisheries Society, Bethesda

Wharton G, Mohajeri SH, Righetti M (2017) The pernicious problem of streambed colmation: a multi-disciplinary reflection on the mechanisms, causes, impacts, and management challenges. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Water 4(5):e1231. https://doi.org/10.1002/wat2.1231

Wilkes MA, Gittins JR, Mathers KL, Mason R, Casas-Mulet R, Vanzo D, McKenzie M, Murray-Bligh J, England J, Gurnell A, Jones JI (2019) Physical and biological controls on FS transport and storage in rivers. Wires Water 6:2–48

Wood PJ, Armitage PD (1997) Biological effects of FS in the lotic environment. Environ Manag 21:203–217

Wood PJ, Toone J, Greenwood MT, Armitage PD (2005) The response of four lotic macroinvertebrate taxa to burial by sediments. Arch Hydrobiol 163:145–162

Wood PJ, Armitage PD, Hill MJ, Mathers KL, Millett J (2016) Faunal responses to fine sediment deposition in urban rivers. In: Gilvear DJ, Greenwood MT, Thoms MC, Wood PJ (eds) River science: research and management for the 21st century. Wiley, Chichester, pp 223–258

Zweig LD, Rabeni CF (2001) Biomonitoring for deposited sediment using benthic invertebrates: a test on 4 Missouri streams. J N Am Benthol Soc 20:643–657

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by a University of Worcester PhD studentship, which was awarded to George Bunting (GB). We are very thankful to the River Communities Group of Queen Mary, University of London for hosting GB during the summer of 2015 and for providing free use of the stream mesocosms. John Murphy, Amanda Arnold and James Pretty of the River Communities Group are thanked for assisting GB with logistical support and in invertebrate identification. Many thanks to Matt Hill and Mélanie Milin at the University of Huddersfield for providing statistical guidance to VSM. Lastly, thank-you to James Atkins for assistance with the initial mesocosm site setup and Heather Taylor at the University of Worcester for creating a site map in Fig. 1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article. In addition, the authors have no financial or proprietary interests in any material discussed in this article. Please note that this study was funded by a University of Worcester PhD studentship, which was awarded to Dr George Bunting.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Milner, V.S., Maddock, I.P., Jones, I. et al. Do legacy effects of deposited fine sediment influence the ecological response of drifting invertebrates to a fine sediment pulse?. Aquat Sci 83, 70 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00027-021-00825-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00027-021-00825-4