Abstract

An approximate analysis of the problem of the transient free convective transfer flow of a Newtonian non-gray optically thin fluid past an isothermal vertical oscillating porous plate in the presence of chemical reaction and heat generation/absorption is studied. The dimensionless governing coupled linear partial differential equations are solved using a spectral relaxation method. The essence of the method of the solution-spectral relaxation method SRM is to linearize and decouple the original system of PDEs to form a sequence of independent linear equations that can be solved iteratively. The SRM approach applies the spectral collocation method and a finite different method independently in all underlying independent variables to obtain approximate solutions of the problem. Detailed computations on the influence of the chemical reaction parameter \(A_{2}\), the thermal radiation parameter R, the number Sc, the heat absorption/generation parameter \(Q_{1}\), and the Prandtl number on the flow velocity, temperature, and concentration distributions are illustrated graphically and in table format. It is observed that the flow velocity increases with the increase in either thermal radiation or thermal Grashof number. The temperature profile increases with the increase in either the thermal radiation parameter or the heat absorption/generation parameter. The rate of heat transfer decreases with the increase in the thermal radiation parameter, whereas it increases with increasing value of the heat generation/absorption parameter.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The phenomenon of free convection arises in the fluid, when temperature changes cause density variation leading to buoyancy forces acting on the fluid element. This can be seen in our everyday life in atmospheric flow which is driven by temperature differences. Free convection flow is a significant factor in several practical applications, which include, for example, cooling of electronic components, in designs related to thermal insulation, material processing, and geothermal systems, etc.

Extensive research has been conducted on free convection flow past a vertical plate see for instance Ostrach [1] and many others. Free convection at a vertical plate with transpiration was investigated by Kolar and Sastri [2]. Ramanaiah and Malarvizi [3] considered natural convection adjacent to a surface with three thermal boundary conditions. Pop and Soundalgekar [4] investigated the free convection flow past an accelerated infinite plate. Raptis et al. [5] studied the unsteady free convective flow through a porous medium adjacent to a semi-infinite vertical plate using finite difference scheme. Singh and Soundalgekar [6] investigated the problem of transient free convection in cold water past an infinite vertical porous plate. Flows past a vertical plate oscillating in its own plane have many industrial applications. The first exact solution of the Navier-Stokes equation was given by Stoke [7] which is concerned with flow of viscous incompressible fluid past a horizontal plate oscillating in its own plane. Natural convection effects on the Stokes problem was further investigated by Soundalgekar [8]. The same problem was considered by Senapati et al. [9] for an impulsively started or oscillating plate. Gupta et al. [10] analyzed flow in the Ekman layer on an oscillating plate. An exact solution to the flow of a viscous incompressible unsteady flow past an infinite vertical oscillating plate with variable temperature and mass diffusion by taking into account of the homogeneous chemical reaction of first order was investigated by Muthucumarswamy and Meenakshisundaram [11]. Kishore et al. [12] studied hydromagnetics flow of a viscous incompressible fluid past an oscillating vertical plate embedded in a porous medium with radiation, viscous dissipation and variable heat, and mass diffusion. The governing equations were solved numerically. It is observed that plate oscillation, variable mass diffusion, radiation, viscous dissipation, and a porous medium affect the flow profiles significantly. The process of heat and mass transfer in free convection flow have attracted the attention of a number of scholars due to its application in many branches of science and engineering, viz. in the early stages of melting adjacent to heated surfaces, in chemical engineering processes which are classified as a mass transfer processes, in a cooling device. Gupta and Gupta [13] studied the heat and mass transfer corresponding to the similarity solution for the boundary layer flow over an isothermal stretching sheet subject to blowing or suction. Elbashbeshy [14] investigated heat transfer over a stretching surface with variable and uniform surface heat flux subject to injection and suction.

In the above mentioned studies the effects of linear heat generation (heat sources/sinks) have not been considered and due to its versatile applicability to ceramic tiles production, the study of heat transfer in the presence of a source/sink has acquired newer dimensions. The study of heat generation or absorption in moving fluids is important in problems dealing with chemical reactions and those concerned with dissociating fluids. Possible heat generation effects may alter the temperature distribution; and, consequently, the particle deposition rate in nuclear reactors, electronic chips, and semi-conductor wafers. Also, heat generation or absorption effects in moving fluids are important in view of several physical problems, such as fluids undergoing exothermic or endothermic chemical reactions. Vajravelu and Hadjinicolaou [15] studied the convective heat transfer in an electrically conducting fluid near an isothermal stretching sheet and they studied the effect of internal heat generation or absorption. Chamkha [16] investigated unsteady convective heat and mass transfer past a semi-infinite porous moving plate with heat absorption. Hady et al. [17] studied the problem of free convection flow along a vertical wavy surface embedded in electrically conducting fluid saturated porous media in the presence of an internal heat generation or absorption effect.

The growing need for chemical reaction in industries and engineering requires the study of heat and mass transfer in the presence of different conditions and parameters with a chemical reaction. There are many transfer processes that are governed by the combined action of buoyancy forces due to both thermal and mass diffusion in the presence of a chemical reaction. Chemical reactions can be classified as either homogeneous or heterogeneous processes. A homogeneous reaction is one that occurs uniformly through a given phase. In contrast, a heterogeneous reaction takes place in a restricted region or within the boundary of a phase. A reaction is said to be of first order if the rate of reaction is directly proportional to the concentration itself, which has many applications in different chemical engineering processes and other industrial applications such as polymer production, manufacturing of ceramics or glassware, and food processing [18]. It has many applications in nuclear reactor and combustion, solar collectors, drying, dehydration operations in chemical and food processing plants, polymer production, etc. The effect of a chemical reaction on a moving isothermal vertical surface with suction has been considered by Muthucumarswamy [19]. Considering this in the study of a chemical reaction, Das et al. [20] considered the effects of a first-order chemical reaction on the flow past an impulsively started infinite vertical plate with constant heat flux and mass transfer. Muthucumarswamy [21] and [19] studied a first-order homogeneous chemical reaction on flow past an infinite vertical plate. Anderson et al. in 1994 have studied the diffusion of a chemically reactive species from a linearly stretching sheet. Anjalidevi and Kandasamy [22] investigated the effect of a chemical reaction on the flow along a semi-infinite horizontal plate in the presence of heat transfer. Reference [23] studied the effect of a chemical reaction on the flow in the presence of heat transfer and magnetic field. Muthucumarswamy and Ganesan [24] analyzed the effect of a chemical reaction on the unsteady flow past an impulsively started semi-infinite vertical plate, which is subject to uniform heat flux. On the other hand, radiation heat transfer effects from a porous wall on free convective flow are very important in space technology and high temperature processes, and very little is known about the effects of radiation on the boundary layer of a radiative fluid past a body. The inclusion of radiation effects in the energy equation leads to a highly non-linear partial differential equation. Actually, many processes in new engineering areas occur at high temperature and knowledge of radiation heat transfer becomes imperative for the design of the pertinent equipment. Nuclear power plants, gas turbines, and the various propulsion devices for aircraft, missiles, satellites, and space vehicles are examples of such engineering areas. The radiation effects of the free convective flow of a gas past a semi-infinite flat plate was studied by Soundalgekar et al. [25] using the Cogley-Vincenti-Giles equilibrium model [26]. Hossain and Takhar [27] studied the effects of radiation of an optically dense viscous incompressible fluid past a heated vertical plate with uniform free stream velocity and surface temperature. In similar research work, Makinde [28] investigated the effect of thermal radiation on the free convective flow and mass transfer past a moving vertical porous plate using a superposition method and reported that increase in thermal radiation intensity will definitely enhance the fluid velocity and promote a boundary layer within the flow regime. In this analysis, consideration had been given to gray gases that emit and absorb, but do not scatter thermal radiation; they noted that the Rosseland diffusion approximation provides one of the most straightforward simplifications of the full integro-partial differential equations.

In view of the significance of the radiation effect as well as the chemical reaction and heat generation effects, we propose in the present paper to investigate the effects of radiation on free convective heat and mass transfer past an isothermal vertical oscillating porous plate in the presence of a chemical reaction and heat generation, using a spectral relaxation method. The governing boundary layer equations are transformed using dimensionless quantities to yield a coupled linear system of partial differential equations. The transformed governing equations are an approach using a spectral relaxation method. The spectral relaxation method is a new numerical method, proposed by Motsa [29], that can be used to solve linear and non-linear systems of boundary value problems. Our main objectives are to study the effect of the radiation parameter and heat generation on the flow and transport characteristics using SRM. Our work is an extension to the work done by Muthucumaraswamy and Janakiraman [30] by considering the effect of thermal diffusion and heat generation on the flow and heat and mass transfer.

2 Problem formulation

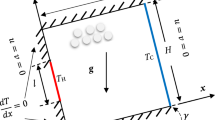

Unsteady flow of a viscous incompressible fluid past an impulsively started infinite isothermal vertical oscillating plate with mass diffusion, in the presence of homogeneous chemical reaction of the first order, thermal radiation and a heat generation source, is investigated. We consider an unsteady flow of a viscous incompressible fluid which is initially at rest and surrounds an infinite vertical plate with temperature \(T_{\infty}\) and concentration \(C'_{\infty}\). The x-axis is taken along the plate in the vertically upward direction and the y-axis is taken normal to the plate. Initially, it is assumed that the plate and the fluid are of the same temperature and concentration. At time \(t'>0\), the plate starts oscillating in its own plane with frequency \(\omega'\) and the temperature of the plate is raised to \(T_{w}\) and the concentration level near the plate is also raised to \(C'_{w}\). It is assumed that there exists a first-order chemical reaction between the fluid and the species concentration. The contribution of the thermal radiative heat loss is based on a Rosseland approximation. Most of the effort in understanding fluid radiation is devoted to the derivation of a reasonable simplification. The Rosseland approximation requires that the medium is optically dense and radiation travels only a short distance before being scattered or absorbed. Then by Rosseland and Boussinesq’s approximations, the unsteady flow is governed by the following equations:

subject to

The continuity equation on integration gives

where \(V_{o}\) is the normal velocity of suction and injection at the wall according to whether \(V_{o}>0\) or \(V_{o}<0\), respectively, \(V_{o}=0\) represents a non-permeable wall. As the plate is assumed to be infinite in length, the physical variables are functions of \(y'\) and \(t'\) only. Here \(u'\) is the velocity in the \(x'\) direction, the time \(t'\), g is the acceleration due to gravity, \(\beta_{t}\) is the volumetric coefficient of thermal expansion, \(\beta_{c}\) the volumetric coefficient of expansion for concentration, T the temperature of the fluid near the plate, \(T_{\infty}\) is the temperature of the fluid far away from the plate, C the species concentration in the fluid far away from the plate, \(C'_{\infty}\) the species concentration at the plate, τ the characteristic time, ν the kinematic viscosity, ρ the density, \(C_{p}\) the specific heat at constant pressure, α the thermal diffusivity, and D is the mass diffusion coefficient.

In this paper, the effect of thermal radiation is studied on the flow to further establish the radiative heat loss due to thermal radiation during convection. It is necessary to point out that most of the effort in understanding the fluid thermal radiation is primarily devoted to the derivation of reasonable simplification of the model [31]. One of these models was proposed by Cogley et al. [32] with the assumption that the fluid is in the optically thin limit and accordingly the fluid does not absorb its own radiation but only absorbs the radiation emitted by the flow boundaries. But for optically thick fluid such as gas,the self-absorption rises and the situation become difficult. However, such a problem can be simplified by using the so-called Rosseland approximation (Rosseland, 1936). The Rosseland approximation requires that the medium is optically dense and radiation travels only a short distance before being scattered or absorbed. We are concerned with the study of thermal radiation of heat within the optically thick fluid before the heat is scattered. Hence radiative heat transfer is taken into account and the Rosseland equation is used to model the thermal radiation of the working fluid. The Rosseland equation is a simplified model of radiative transfer equation (RTE). When the working fluid has a great extinction coefficient, it can be treated as an optically thick fluid. \(q_{r}\) is the radiative heat flux and is defined using the Rosseland approximation [33, 34] as

where \(\sigma^{*}\) is Stefan-Boltzmann constant and \(K^{*}\) is called the absorption coefficient. We assumed that the temperature difference within the flow regime is sufficiently small such that \(T^{4}\) can be expressed as a linear function of the free stream temperature of the flow. This can be derived by expanding \(T^{4}\) in a Taylor series about \(T_{\infty}\) and neglecting higher-order terms. We consider the Taylor series expansion of a function \(f(x)\) about \(x_{0}\),

Likewise, we have an expansion of \(T^{4}\) about \(T_{\infty}\). Set \(f(x)=T^{4}\) and \(f(x_{0})=f(T_{\infty})=T^{4}_{\infty}\) in the above equation. Neglecting higher orders, we obtain

Thus

To facilitate approximate solutions to the model, we introduce the following dimensionless quantities:

into the governing equations (1)-(4) and obtain

subject to the transformed boundary conditions:

where R is the thermal radiation parameter, Pr is the Prandtl number, \(A_{2}\) is the chemical reaction parameter, ω is the phase angle, Gr is the thermal Grashof number, Gc is the Grashof mass number, Sc is the Schmidtl number, and \(Q_{1}\) is the heat absorption generation parameter.

3 Numerical method: spectral relaxation method (SRM)

Here, we discuss the application of the numerical method called the spectral relaxation method (SRM) to obtain an approximate solution of the partial differential equations (14)-(16) subject to conditions (17)-(18). In the application of SRM, it is fundamental to apply an efficient linearization technique to derive a system of linear equations that can be discretized using basic discretization scheme.

The SRM as proposed by Motsa [35, 36] adopts the Gauss-Seidel approach to decouple non-linear systems of equations. Similarly, in this section we apply the Gauss-Seidel technique to linearize and decouple the system of equations (14)-(16). Afterward, the equations of the resulting system are discretized to obtain iterative schemes that evaluate the linear terms at the current iterating level, denoted by \((r+1)\), and the non-linear terms at the previous level, represented as \((r)\). Adopting the SRM steps mentioned above on the systems of non-linear partial differential equations yields the following linear PDEs:

subject to

where the coefficient parameter \(a_{1,r}\) is defined as

The initial approximation for solving equations (19)-(23) are obtained at \(\tau= 0\) with due consideration of the boundary conditions (22)-(23). Hence, \(u_{0}(\eta,\tau)\), \(\theta_{0}(\eta,\tau)\), \(\phi_{0}(\eta, \tau)\) are given as

The system of equations (19)-(21) can be solved iteratively for the unknown functions by adopting the initial approximations given in (24)-(26) as starting values. The iteration schemes (19), (20), and (21) are solved iteratively for \(u_{r+1}(\eta,\tau)\), \(\theta_{r+1}(\eta ,\tau)\), and \(\phi_{r+1}(\eta; \tau)\) when \(r=0,1,2,\ldots \) .

To solve the system of equations (19)-(21), the equations are first discretized using the Chebyshev spectral collocation method with respect to an η independent variable and, second, the implicit forward finite difference method in the τ direction. The finite difference scheme is used with centering about a mid-point between \(\tau^{n+1}\) and \(\tau^{n}\). The mid-point of the scheme is expressed as

Thus, implementing the centering about \(\tau^{n+\frac{1}{2}}\) for the unknown functions, say \(u(\eta,\tau)\) and its associated derivative, we obtain

Suppose we apply the Chebyshev spectral collocation method on the system of equations (19)-(21) before applying the finite differences. We obtain

Now we apply the forward finite difference scheme defined in equation (27) to equations (28)-(30), in the τ-direction with centering about the mid-point \(\tau^{n+\frac{1}{2}}\) to obtain the following systems of decoupled equations:

subject to the following initial and boundary conditions:

where \(w'= \cos\omega\tau\). The matrices above are defined as follows:

We note that I is an identity matrix of size \((N_{x} + 1)\ast(N_{x} + 1)\), U, Θ, and Φ are the vectors of the unknown functions u; θ and ϕ evaluated at the grid points and 0 is a zero vector of size \((N_{x}+1) \ast1\). The boundary conditions (35)-(36) are imposed on the first and last rows of (32)-(34) as follows:

where

Hence, by adopting the initial approximations given by equations (24)-(26) for \(u_{0}(\tau,\eta)\), \(\theta_{0}(\tau,\eta )\) and \(\phi_{0}(\tau,\eta)\), respectively, equations (32)-(34) are solved iteratively to obtain approximate solutions for the unknown functions \(U_{r+1}(\tau,\eta)\), \(\theta _{r+1}(\tau,\eta)\), and \(\phi_{r+1}(\tau,\eta)\), with \(r = 0,1,2,3,\ldots \) .

From the velocity, temperature, and concentration profiles, we now study the effects of the various parameters on the skin-friction coefficient, the local heat transfer rate (Nusselt number), and the mass transfer rate (Sherwood number). In practical engineering applications, the physical quantities of practical values are the local skin friction coefficient, the local Nusselt number of the flow, and the Sherwood number. These are defined according to [30] as

Using the dimensional quantities in equations (8)-(10), the quantities above can be represented by

4 Results and discussion

We have presented an approximate solution for the non-dimensional velocity, temperature, and concentration profiles at various values of pertinent parameters of the flow, in Figures 1-8. For the purpose of numerical validation of our work, we have taken fixed values of \(A_{2}=\mathit{Gr}=\mathit{Gc}=2\), \(\mathit{Pr}=0.72\), \(\omega =\pi /6\), \(R=0.5\), \(\mathit{Sc}=0.62\), and \(\tau=0.5\), so as to obtain a clear insight into the physics of the problem. Figure 1 represents the effect of the Prandtl number Pr on the velocity, temperature, and concentration profiles of the flow field. It is obvious that the Prandtl number has no significant impact on the concentration profiles of the flow as shown in Figure 1 and equation (16), but the velocity and temperature profiles of the flow decrease as the Prandtl number increases. The temperature and thermal boundary layer thickness are decreased corresponding to an increase in the values of the Prandtl number. The Prandtl number is inversely proportional to the thermal diffusivity. A larger Prandtl number implies smaller diffusivity. This smaller thermal diffusivity shows a reduction in the momentum and thermal boundary layer thickness. Figure 2 illustrates the influence of the non-dimensional chemical reaction parameter \(A_{2}\) on the velocity, temperature, and concentration profile of the flow. The effect of the chemical reaction parameter is very important in the concentration field. It can be inferred from Figure 2 that the velocity and concentration profiles of the fluid decrease with increasing values of the chemical reaction parameter \(A_{2}\). This is because an increase in the chemical reaction parameter speeds up the rate of the reactants on the flow and consequently reduces the concentration distribution of the reacting species. The chemical reaction increases the rate of interfacial mass transfer. The chemical reaction reduces the local concentration, and it thus increases its concentration gradient and its flux. There is little or no significant effect of the chemical reaction parameter on the temperature profile of the flow. That is, we observe that \(A_{2}\) has a negligible effect on the temperature distribution of the flow.

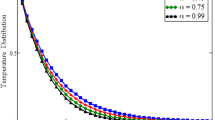

The graph of velocity, temperature, and concentration profiles at different values of the phase angle ω are shown in Figure 3. The numerical results show that an increase in the phase angle ω results in a reduction of the velocity distribution but has a negligible effect on the temperature and concentration profiles. Figure 4, first graph, shows the influence of the thermal buoyancy force parameter Gr on the velocity. As can be seen from this figure, the velocity profile increases with the increase in the values of the thermal buoyancy parameter (i.e. the thermal Grashof number). It is observed that the velocity profile momentarily increases in the boundary layer region. The buoyancy force acts like a favorable pressure gradient, which accelerates the fluid within the boundary layer and hence increases the boundary layer thickness. The solutal buoyancy force parameter Gc has the same effect on the velocity profile as Gr (see Figure 5(left)). There is little or no significant effect of the thermal Grashof number on the temperature and concentration profiles of the flow. Figure 6 depicts the effect of varying thermal radiation parameter R on the flow velocity, temperature, and concentration flow. We observe that the thermal radiation enhances convective flow in such a way that the flow velocity increases with the increase in the thermal radiation parameter R. We observe that the thermal radiation enhances heat transfer as the thermal boundary layer thickness increases with the increase in the thermal radiation. The temperature distribution is enhanced with an increase in the thermal radiation parameter. Larger values of thermal radiation parameter provide more heat to the working fluid, which results in an enhancement in the temperature and thermal boundary layer thickness. There is no significant effect of the thermal radiation parameter on the concentration distribution in flow. The effect of the Schmidt number Sc on the flow profiles is shown in Figure 7. It can be seen from the figures that, as the Schmidt number increases, the flow velocity and volume fraction (concentration profile) decrease across the boundary layer region. A higher Schmidt number implies a lower Brownian diffusion coefficient, which will give rise to a shorter penetration depth for the concentration boundary layer. The effect of the Schmidt number on the temperature distribution is not significant. Figure 8 illustrates the influence of the heat absorption coefficient \(Q_{1}\) on the velocity, temperature, and concentration distributions. Physically, the presence of heat absorption (thermal sink) on a flow often leads to a net reduction in the flow velocity. This behavior is seen from the first part of Figure 8 in which the velocity decreases as \(Q_{1}\) increases. The hydrodynamic boundary layer decreases as the heat absorption effects increase. Figure 8(right) depicts the effects of the heat absorption parameter \(Q_{1}\) on the temperature distribution. It is observed that the boundary layer generated more heat energy into the flow and thereby raised the temperature profile of the flow. This is because when heat is gained, the buoyancy force increases the temperature profile.

Numerical results of the skin-friction coefficient τ∗, the Nusselt number Nu, and the Sherwood number Sh against the thermal radiation parameter and heat absorption/generation parameter are presented in tabular form in Tables 1 and 2. The influence of thermal radiation on the skin friction coefficient, the Nusselt number, and the Sherwood number is shown in Table 1. We clearly observe from the table that the absolute values of the skin-friction coefficient increases as the thermal radiation parameter R increases. The thermal radiation parameter has an opposite effect on the Nusselt number. It is seen in Table 2 that the skin-friction coefficient and the local heat transfer rate (Nusselt number) increase with the increase in the heat generation parameter.

5 Conclusion

This study presented an approximate analysis on the problem of a transient free convective transfer flow of a Newtonian non-gray optically thin fluid past an isothermal vertical oscillating porous plate in the presence of a chemical reaction and heat generation/absorption. The coupled non-linear governing equations were solved using the spectral relaxation method. In this paper, the spectral collocation method derived in terms of Lagrange interpolation polynomials and adapted to decoupled non-linear systems of partial differential equations using relaxation techniques has been applied. The application of the method was found to be straightforward because it does not depend on any linearization, expansions and the discretization of the ordinary or partial derivatives whcih has its basis on simple formulas. The influence of various physical parameters such as the heat generation parameter, the Prandtl number, the Schmidtl number, thermal radiation, etc., were also investigated and analyzed. Our findings reveal that:

- ⋄:

-

Buoyancy parameters such as the thermal Grashof number and the mass Grashof number increase the velocity distribution within the momentum boundary layer.

- ⋄:

-

The presence of heat absorption enhances the temperature distribution and reduces the fluid velocity profile.

- ⋄:

-

The concentration distribution decreases with increasing value of the chemical reaction parameter.

- ⋄:

-

Both the velocity and the temperature profiles increase with increasing values of thermal radiation parameter.

References

Ostrach, S: Analysis of laminar free convective flow and heat transfer about a flat plate parallel to direction of the generating body force. NACA technical report 1111 (1952)

Kolar, AK, Sastri, VM: Free convective transpiration over a vertical plate: a numerical study. Heat Mass Transf. 23, 327-336 (1988)

Ramanaiah, G, Malarvizi, G: Unified treatment of free convection adjacent to a vertical plate with three thermal boundary conditions. Heat Mass Transf. 27, 393-396 (1992)

Pop, I, Soundalgekar, VM: Free convection flow past an accelerated infinite plate. Z. Angew. Math. Mech. 60, 167-168 (1980)

Raptis, A, Singh, AK, Rai, KD: The unsteady free convective flow through a porous medium adjacent to a semi-infinite vertical plate using finite difference scheme. Mech. Res. Commun. 14, 9-16 (1987)

Singh, AK, Soundalgekar, VM: Transient free convection in cold water past an infinite vertical porous plate. Int. J. Energy Res. 14, 413-420 (1990)

Stokes, GG: On the effect of the internal friction of fluid on the motion of pendulum. Trans. Camb. Philos. Soc. 9, 8-106 (1851)

Soundalgekar, VM: Free convection effects on the flow past a vertical oscillating plate. Astrophys. Space Sci. 64, 165-172 (1979)

Senapati, N, Dhal, RK, Das, TK: Effects of chemical reaction on free convection MHD flow through porous medium bounded by vertical surface with slip flow region. Am. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2(3), 124-135 (2012). doi:10.5923/j.ajcam.20120203.10

Gupta, AS, Misra, JC, Reza, M, Soundalgekar, VM: Flow in the Ekman layer on an oscillating porous plate. Acta Mech. 165, 1-16 (2003)

Muthucumaraswamy, R, Meenakshisundaram, S: Theoretical study of chemical reaction effects on vertical oscillating plate with variable temperature. Theor. Appl. Mech. 33(3), 245-257 (2006)

Kishore, PM, Rajesh, V, Verma, SV: The effects of thermal radiation and viscous dissipation on MHD heat and mass diffusion flow past an oscillating vertical plate embedded in a porous medium with variable surface conditions. Theor. Appl. Mech. 39(2), 99-125 (2012)

Gupta, PS, Gupta, AS: Heat and mass transfer on a stretching sheet with suction or blowing. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 55, 744-746 (1977)

Elbashbeshy, EMA: Heat transfer over a stretching surface with variable surface heat flux. J. Phys. D, Appl. Phys. 31, 1951-1958 (1988)

Vajravelu, K, Hadjinicolaou, A: Convective heat transfer in an electrically conducting fluid at a stretching surface with uniform free stream. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 35(12-13), 1237-1244 (1997)

Chamkha, AJ: Unsteady MHD convective heat and mass transfer past a semi-infinite vertical permeable moving plate with heat absorption. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 24, 217-230 (2004)

Hady, FM, Mohamed, RA, Mahdy, A: MHD free convection flow along a vertical wavy surface with heat generation or absorption effect. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 33, 1253-1263 (2006)

Cussler, EL: Diffusion: Mass Transfer in Fluid Systems, 2nd edn. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1997)

Muthucumarswamy, R: Effects of a chemical reaction on moving isothermal vertical surface with suction. Acta Mech. 155(1-2), 65-70 (2002). doi:10.1007/BF01170840

Das, UN, Deka, RK, Soundalgekar, VM: Effects of mass transfer on flow past an impulsively started infinite vertical plate with constant heat flux and chemical reaction. Forsch. Ingenieurwes. 60(10), 284-287 (1994). doi:10.1007/BF02601318

Muthucumaraswamy, R, Ganesan, P: On impulsive motion of a vertical plate with heat flux and diffusion of chemically reactive species. Forsch. Ingenieurwes. 66, 17-23 (2000)

Anjalidevi, SP, Kandasamy, R: Effects of chemical reaction, heat and mass transfer on laminar flow along a semi infinite horizontal plate. Heat Mass Transf. 35, 465-467 (1999)

Anjalidevi, SP, Kandasamy, R: Effects of chemical reaction, heat and mass transfer on MHD flow past a semi infinite plate. Z. Angew. Math. Mech. 80, 697-700 (2000)

Muthucumarswamy, R, Ganesan, P: First order chemical reaction on flow past an impulsively started vertical plate with uniform heat and mass flux. Acta Mech. 147(1-4), 45-57 (2001). doi:10.1007/BF01182351

Soundalgekar, VM, Takhar, HS, Vighnesam, NV: The combined free and forced convection flow past a semi-infinite plate with variable surface temperature. Nucl. Eng. Des. 110, 95-98 (1960)

Cogely, AC, Vinceti, WG, Giles, SE: Differential approximation for radiative heat transfer in a non-gray gas near equilibrium. AIAA J. 6, 551-553 (1968)

Hossain, MA, Takhar, HS: Radiation effect on mixed convection along a vertical plate with uniform surface temperature. Heat Mass Transf. 31, 243-248 (1996)

Makinde, OD: Free convective flow with thermal radiation and mass transfer past a moving vertical porous plate. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 32, 1411-1419 (2005)

Motsa, SS: A new spectral relaxation method fora similarity variable nonlinear boundary layer flow systems. Chem. Eng. Commun. 201, 241-256 (2014)

Muthucumaraswamy, R, Janakiraman, B: Mass transfer effects on isothermal vertical oscillating plate in the presence of chemical reaction. Int. J. Appl. Math. Mech. 4(1), 66-74 (2008)

Aboeldahab, EM, El Gendy, MS: Radiation effect on MHD free-convective flow of a gas past a semi-infinite vertical plate with variable thermophysical properties for high-temperature differences. Can. J. Phys. 80, 1609-1619 (2002)

Cogley, AC, Vincenty, WG, Gilles, SE: Differential approximation for radiative transfer in a non-grey gas near equilibrium. AIAA J. 6, 551-553 (1968)

Raptis, A: Radiation and free convection flow through a porous medium. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 25, 289-295 (1998)

Sparrow, EM, Cess, RD: Radiation Heat Transfer: Augmented Edition, Chapters 1 and 7. Hemisphere, Washington (1978)

Motsa, SS, Dlamini, PG, Khumalo, M: Solving hyperchaotic systems using the spectral relaxation method. Abstr. Appl. Anal. 2012, Article ID 203461 (2012). doi:10.1155/2012/203461

Motsa, SS, Dlamini, PG, Khumalo, M: A new multistage spectral relaxation method for solving chaotic initial value systems. Nonlinear Dyn. 72(1-2), 265-283 (2013)

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to SS Motsa for his kind assistance with spectral relaxation method (SRM), and Boneze Chika who moderated this paper and in that sense improved the manuscript significantly.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Abbreviations

English symbols: \(c_{p}\): specific heat at constant pressure; \(V_{0}\): normal velocity of suction and injection at the wall; Sc: Schmidtl number; g: acceleration due to gravity; \(G_{r}\): thermal Grashof number; \(G_{m}\): Grashof mass number; Pr: Prandtl number; \(q_{r}\): radiative heat flux; R: thermal radiation parameter; \(A_{2}\): chemical reaction parameter; \(Q_{1}\): heat absorption generation parameter; \(T_{\infty}\): free stream temperature of the working fluid; \(C'_{\infty}\): free stream concentration of the working fluid; D: mass diffusivity of the fluid; \(u'\), \(v'\): velocity component in \(x'\)- and \(y'\)-direction, respectively; Nu: Nusselt number; Sh: Sherwood number; u: dimensionless velocity function. Greek symbols: μ: dynamic viscosity; ρ: density of the fluid; α: thermal diffusivity term; \(\sigma^{*}\): Stefan-Boltzmann constant; \(K^{*}\): absorption coefficient; \(\tau^{*}\): skin-friction coefficient; η: similarity variable along y; \(\beta_{t}\): thermal expansion coefficient; \(\beta_{c}\): species expansion coefficient; λ: thermal conductivity; ω: phase angle; τ: dimensionless time variable; θ: dimensionless temperature function; ϕ: dimensionless concentration function; \(\rho_{\infty}\): ambient density of the working fluid.

Competing interests

The authors of this publication certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest (such as honoraria; educational grants; participation in speakers’ bureaus; membership, employment, consultancies, stock ownership, or other equity interest; and expert testimony or patent-licensing arrangements), or non-financial interest (such as personal or professional relationships, affiliations, knowledge or beliefs) in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Authors’ contributions

AJO conceived the research study, set the research direction, gave motivation, and participated solely in the modeling of the physical system this research represented. He also studied the relevant literature relating to this research work. AIF delved into how to proffer mathematical solutions to the system of partial differential equations resulting from the model problem. AIF carried out the model analysis, proffered a method of solution, simulated the model to obtain numerical results, discussed the results and drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

AJO is a senior lecturer at the Federal University of Technology, Akure. His area of interest has been boundary layer theory, MHD flow, and numerical analysis. AIF is a self-motivated researcher with genuine interest in applied mathematics. AIF’s research interest focuses on geophysical fluid dynamics, and on computational fluid dynamics with a keen interest to learn more on modeling of fluid flow through a porous media and derivation of robust numerical methods and scientific computing to the physical problems that arise from interactions between flow and its environment as well as practical problems in engineering. AIF’s research is a well-balanced combination of analytical investigations and numerical experiments using finite difference, spectral approach, and other approximation methods. AIF’s current research entails the development of reliable numerical schemes for mathematical models arising in geothermal flow in porous media as well as other PDE problems.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Fagbade, A.I., Omowaye, A.J. Influence of thermal radiation on free convective heat and mass transfer past an isothermal vertical oscillating porous plate in the presence of chemical reaction and heat generation-absorption. Bound Value Probl 2016, 97 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13661-016-0601-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13661-016-0601-z