Abstract

Background

Human adenoviruses (HAdVs) cause a wide range of diseases. However, the genotype diversity and epidemiological information relating to HAdVs among hospitalized children with respiratory tract infections (RTIs) is limited. Here, we describe the epidemiology and genotype distribution of HAdVs associated with RTIs in Beijing, China.

Methods

Nasopharyngeal aspirates (NPA) were collected from hospitalized children with RTIs from April 2017 to March 2018. HAdVs were detected by a TaqMan-based quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) assay, and the hexon gene was used for phylogenetic analysis. Epidemiological data were analyzed using statistical product and service solutions (SPSS) 21.0 software.

Results

HAdV was detected in 72 (5.64%) of the 1276 NPA specimens, with most (86.11%, 62/72) HAdV-positives cases detected among children < 6 years of age. HAdV-B3 (56.06%, 37/66) and HAdV-C2 (19.70%, 13/66) were the most frequent. Of the 72 HAdV-infected cases, 27 (37.50%) were co-infected with other respiratory viruses, most commonly parainfluenza virus (12.50%, 9/72) and rhinovirus (9.72%, 7/72). The log number of viral load ranged from 3.30 to 9.14 copies per mL of NPA, with no significant difference between the HAdV mono- and co-infection groups. The main clinical symptoms in the HAdV-infected patients were fever and cough, and 62 (86.11%, 62/72) were diagnosed with pneumonia. Additionally, HAdVs were detected throughout the year with a higher prevalence in summer.

Conclusions

HAdV prevalence is related to age and season. HAdV-B and HAdV-C circulated simultaneously among the hospitalized children with RTIs in Beijing, and HAdV-B type 3 and HAdV-C type 2 were the most frequent.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

First discovered in 1953 by Rowe et al., human adenoviruses (HAdVs) are non-enveloped, double-stranded DNA viruses belonging to the Mastadenovirus genus (Adenoviridae family). They are common pathogens in children and cause a variety of diseases [1]. HAdV accounts for at least 5 to 10% of pediatric and 1 to 7% of adult respiratory tract infections (RTIs) [2]. There are currently seven different HAdV species (A to G), some of which specifically attack the conjunctiva (species D), the upper and lower respiratory tracts (species B, C and E), and the gastrointestinal tract (species F and G) [3]. Of the 90 AdV serotypes, 55 are known to cause human diseases, with AdV3, 4, 7 and 14 being the most common types to cause respiratory disease outbreaks [4]. HAdV has caused respiratory tract adenovirus outbreaks in Jiangsu and Taiwan provinces of China, as well as in Korea, Singapore and Malaysia [5,6,7]. Such infections have been estimated to cause 2–5% of RTIs overall and 4–10% of all pneumonias in City of Bethlehem [8].

Although HAdVs are associated with mild to moderate disease in most cases, life threatening disease can occur in some patients, particularly if they are immunocompromised [9]. At present, China has not yet established a nationwide epidemiological surveillance program for adenovirus infections, and infections with it do not need to be legally reported, so the institutions for disease control and prevention cannot conduct early detection screening or issue early warnings. Neither are there any U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved antivirals for adenoviral infections [10]. HAdVs play an important role in respiratory infections, particularly in children. Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate the epidemiological, clinical, and molecular characteristics of HAdV infections occurring among children with RTIs in a Chinese tertiary hospital from April 2017 to March 2018. Collectively, the findings from this study underscore the importance of monitoring the epidemiology of HAdV infections and protecting vulnerable patients as part of the suite of infection prevention strategies in hospitals.

Materials and methods

Patients and specimens

The nasopharyngeal aspirate (NPA) samples (1276) used in this study were collected from hospitalized children (< 14 years) with RTIs at Beijing Friendship Hospital between April 2017 and March 2018. Informed consent from the parents or guardians of the children enrolled in the study was received. RTIs was defined as an illness that presented with at least two of the following clinical presentations: fever, cough, nasal obstruction, expectoration, sneeze and dyspnoea during the previous week. Patients, who were diagnosed with pneumonia by chest radiography, were also included in the study, even if they did not show the clinical features described above [11]. All the specimens were stored at − 80 °C until further processing. Demographic and clinical data were obtained from the hospital’s database.

Detection of HAdV and other common respiratory viruses

Total viral nucleic acids were extracted from 200 μL of each clinical NPA specimen using the QIAamp MinElute Kit (Qiagen, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and eluted with 60 μL of nuclease-free water. HAdV detection was performed using qPCR assay targeting the highly conserved gene region (132-bp) of the HAdV hexon. TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, USA) was used to amplify HAdV hexon DNA using specific primers (Forward:5′- GCCCCAGTGGTCTTACATGCACATC-3′; Reverse: 5′-GCCACGGTGGGGTTTCT AAACTT-3′) and probe (5′-FAM-TGCACCAGACCCGGGCTCAGGTACTCCGA- 3′-TAMRA) [12]. Each 20 μL reaction mixture comprised 10 μL of 2 × TaqMan Gene Expression Master Mix, 1.8 μL of each primer (10 pM), 0.2 μL of probe (10 pM), 4.2 μL of sterile water, and 2.0 μL of the nucleic acid components extracted from each sample. The qPCR cycling program was as follows: 50 °C for 2 min, 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s, and 60 °C for 1 min. Samples with a cycle threshold (Ct) < 38 were regarded as positive. 10-fold serial dilutions of pMD18-T/Hexon plasmid from 1010 to 100 copies per μL were prepared to establish a standard curve to measure the HAdV load. qPCR were performed using the Mx3005P qPCR System (Agilent Stratagene, USA). HAdV-positive samples were subsequently screened for the following pathogens: influenza A (FluA) and B (FluB) viruses, parainfluenza viruses (PIVs) 1–4, human metapneumovirus (HMPV), human rhinovirus (HRV), WU polyomavirus (WUPyV), respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and human coronaviruses (HCoV) NL63, OC43, 229E, HKU1 and human bocavirus (HBoV), as described previously [13,14,15]. Additionally, mycoplasma pneumonia is determined by the detection of mycoplasma pneumoniae IgM antibody. As for bacterial pneumonia, it was confirmed by sputum culture.

HAdV genotyping

Nested PCR targeting the HAdV hexon gene’s hypervariable region was employed for genotyping. The outer primers used were forward 5′-GCCACCTTCTTCCCCATGGC.

− 3′ and reverse 5′-GTAGCGTTGCCGGCCGAGAA-3′, and the internal primers were forward 5′-TTCCCCATGGCCCACAACAC-3′ and reverse 5′-GCCTCGATGACGCC.

GCGGTG-3′. Nested PCR was conducted in 25 μL volume comprising 2.5 μL of 10 × EXTaq buffer, 1.0 μL (10 pM) of each primer, 2.0 μL of dNTP Mix, 0.5 μL of EXTaq DNA polymerase, 2.0 μL of viral nucleic acid extract or first nested-PCR product, and 16 μL of double-distilled water. The mixtures were amplified with an initial denaturation at 94 °C for 10 min, followed by 36 cycles at 94 °C for 1 min, 55 °C for 1 min, and 72 °C for 2 min, and a 7 min extension at 72 °C. PCR products were analyzed on 1.50% agarose gels, purified, and then confirmed as authentic by sequencing. Samples that failed to amplify are defined herein as untyped.

Phylogenetic analysis

All the hexon gene sequences obtained by nested PCR together with the 26 HAdV strain sequences available in GenBank were used for the phylogenetic analyses. The phylogenetic tree was constructed using molecular evolutionary genetics analysis (Mega) 5.0 and evaluated using 100 bootstrap replicates to verify the HAdV genotypes. Positive PCR products were named according to the corresponding serial numbers of the specimens.

Statistical analysis

The HAdV detection rates for the different populations and different seasons were compared by a χ2 test, and the relationship between vomiting and HAdV types was statistically analyzed by Fisher’s exact probability, with statistical significance set at P < 0.05. Vector NTI 11.0 software was used for sequence alignment and Mega 5.0 software for phylogenetic analysis. Epidemiological data were analyzed using statistical product and service solutions (SPSS) 21.0 software.

Results

Characteristics of the inpatient children

In total, 1276 NPA specimens were obtained from 1276 children with RTIs at Beijing Friendship Hospital, among which 674 (52.82%) were male and 602 (47.18%) were female (Table 1), all children survived, and the age range was from 1 day to 14 years of age with a median age of 3 years. From them, 897 (70.30%) patients were younger than 5 years old.

Epidemiology of HAdV

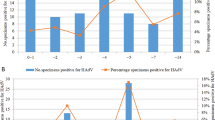

HAdVs were detected in 5.64% (72/1276) of the hospitalized children. As shown in Table 1, among the 72 HAdV-positive patients, 45 (62.50%) were male and 27 (37.50%) were female (a male/female ratio of 1.6:1). No significant difference was observed in males and females in the HAdV-positive cases (P = 0.090). HAdV was detected among hospitalized children (< 14 years) with RTIs at Beijing Friendship Hospital between April 2017 and March 2018, and there were significant differences in HAdV detection rates among different age groups (P = 0.008). Children under 6 years old accounted for 86.11% (62/72) of the infections. The HAdV detection rate peaked in the > 5 to≤6 years age group (12.79%, 11/86), while those in the ≤1 years old group had a relatively low detection rate of 3.18% (10/314). HAdV was detected in every month throughout the study period from April 2017 to March 2018, peaking in summer. The HAdVs detection frequencies were 5.60% (18/321), 9.52% (30/315), 3.31% (10/302) and 4.14% (14/338) (χ2 = 16.06, P = 0.001) in the spring, summer, autumn and winter months, respectively. Additionally, the HAdV detection rate peaked at 10.91% (12/110) in August 2017 (Fig. 1).

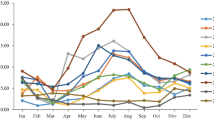

Coinfections with other respiratory viruses

Of the 72 HAdV-infected cases, 27 (37.50%) comprised co-infections with other respiratory viruses including 21 (77.78%, 21/27) with one other virus, 3 (11.11%, 3/27) with two other viruses, 2 (7.41%, 2/27) with three other viruses and 1 (3.70%, 1/27) with four other viruses. The most frequently identified mixed infection was PIV (12.50%, 9/72) and HRV (9.70%, 7/72), as shown in Table 2. Among the HAdV-positive specimens, the log number of HAdV genome copies ranged from 3.30 to 9.14 copies per mL of NPA, as determined by the qPCR assay measurements (Fig. 2). The log number for the HAdV genome copies was 6.14 ± 1.52 copies/mL of NPA in the children infected with HAdV only, which is slightly higher than the 5.70 ± 1.39 copies/mL of NPA from those co-infected with HAdV and other respiratory viruses; there was, however, no significant difference in the viral loads between the HAdV mono- and co-infections (P = 0.220).

Clinical characteristics of the HAdV infections

Sixty-two of the patients (86.11%, 62/72) from the 72 HAdV-positive cases were diagnosed with pneumonia, including 46 with bronchopneumonia, 4 with asthmatic bronchitis, 3 with refractory bronchopneumonia, 8 with pneumonia (3 with mycoplasma pneumonia, 3 with bacterial pneumonia and 2 with viral pneumonia) and 1 with refractory pneumonia. Viral pneumonia and bacterial pneumonia accounts for 3.23% (2/62) and 4.84% (3/62) of the pneumonia, respectively. In addition, the remaining 10 cases were diagnosed with acute tonsillitis (5), acute upper respiratory infection (2), acute bronchitis (2), as well as 1 with Epstein-Barr virus-associated infectious mononucleosis. The main clinical signs in the HAdV-positive patients were fever (97.22%, 70/72) and cough (75%, 54/72), while the other clinical presentation were vomiting (18.06%, 13/72), gasping (15.28%, 11/72), diarrhea (4.17%, 3/72) and angina (5.56%, 4/72). Furthemore, vomiting didn’t associate with specific HAdV types by Fisher’s exact probability (P = 0.069). In this study, of the 72 HAdV-positive children with RTIs, 4 (5.56%, 4/72) had asthma, the other 68 had no pre-existing chronic conditions.

HAdV genotyping and phylogenetic analysis

Basing on the 956-bp fragment of the hexon gene amplified by nested-PCR, 66 HAdV-positive samples were sequenced and successfully genotyped. The phylogenetic analyses indicated that 41 cases belonged to species B (HAdV-B3, HAdV-B7, and HAdV-B35) and 25 belonged to species C (HAdV-C2, HAdV-C1, and HAdV-C5) (Table 3). Six of the samples failed to be typed. The above-mentioned results indicate that species B and C (at least 6 HAdV genotypes) circulated simultaneously in Beijing, and that HAdV-B3 was the most prevalent genotype, followed by HAdV-C2 (Fig. 3).

Discussion

The present study was carried out between April 2017 and March 2018 among hospitalized children with RTIs in Beijing, China. Herein, we describe (i) the prevalence of HAdVs in hospitalized children with RTIs presenting at Beijing Friendship Hospital during a one-year period; (ii) the clinical spectrum of the HAdV-positive RTI patients; (iii) the viral co-pathogens present in the HAdV infections; and (iv) the genetic diversity of the HAdVs.

The clinical characteristics of the RTIs caused by HAdV are very similar to those of influenza, PIV and other respiratory tract pathogens, making it difficult to clinically diagnose this type of infection. Therefore, effective diagnostic methods are needed for rapid identification and genotyping of HAdV. The qPCR assay used herein was established to detect and quantify HAdV. A total of 1276 NPA specimens were screened for the presence of HAdV and 72 specimens (5.64%, 72/1276) were confirmed to be positive for HAdV, which is consistent with prior reports (1.70–13.90%) [16,17,18]. The detection rate for HAdV varies from region to region in China, and the rate for hospitalized children with acute lower RTIs in Zhejiang province from 2006 to 2012 was 0.63, and 2.24% in Shenzhen city from 2012 to 2015 [19, 20]. However, it is worth mentioning that such discrepant HAdV detection rates can be caused by methodological differences, the number of patients tested, the periods during which the samples are collected, and even a study’s duration.

Previous studies have shown that HAdV detection rates are positively correlated with the monthly mean temperature and sunshine duration, and negatively correlated with wind speed; in fact, the higher the air temperature, the higher the detection rate [21]. Our study also revealed that HAdV infections occurred throughout the year with the highest prevalence in the summer (9.52%, Jun to Aug), peaking in August (10.91%), which is similar to what has been found in Tianjin, a northern Chinese city, where HAdV infections are concentrated during the summer [22]. However, this finding is discordant with other studies that have reported seasonal peaks for HAdV infections in spring in Northern China and Mexico [23, 24].

We found that the HAdV infections occurred predominantly in children under 6 years of age (86.11%), demonstrating that HAdV is an important pediatric pathogen. Previous studies drew identical conclusions that most children become infected by HAdV at an early age [18, 25, 26]. HAdVs can be easily transmitted through fomites contaminated with infectious body fluids. In our study, the HAdV detection rate (3.18%) was lowest among children under 1 year of age, and the reasons need to be further explored.

Many studies have reported that the most common HAdV species causing RTIs in children are B (B3, B7, B21), C (C1, C2, C5, C6) and E (E4) worldwide [27, 28]. HAdV 2, 3 and 7 are the most prevalent species and are associated with severe pneumonia in China [29, 30]. In the present study, a total of 66 samples were identified and phylogenetically analyzed based on the hexon gene sequence, which revealed six HAdV genotypes and showed that HAdV species B and C were the most prevalent, accounting for 62.12 and 37.88% of isolates, respectively. Similarly to what has been found in Asia by other authors, HAdV-B3 was the most common type (56.06%, 37/66) followed by HAdV-C2 (19.70%, 13/66) and C1 (10.61%, 7/66). HAdV-B3 has been identified as the causative pathogen for severe acute respiratory illness outbreaks in Korea [31], Brazil [32] and Taiwan [33], and it was the main type of respiratory HAdV infections from 1981 to 2002. Moreover, HAdV-B3 was the pathogen causing epidemic respiratory disease outbreaks in Europe, America, and Oceania. Last, HAdV-B3 is known to cause a characteristic syndrome in older children and adults, as manifested by acute pharyngo-conjunctival fever, especially after contact with summer camps and swimming pools [34]. HAdV- C1 and HAdV-C2 have been frequently reported to cause endemic, sporadic and epidemics cases [35, 36].

In the present study, the most common diagnosis (86.11%) in the HAdV-positive cases was pneumonia, with the common signs and symptoms of fever and cough, which is consistent with previous reports [16,17,18]. HAdV infection is often accompanied by other virus infections. Our study showed that PIV (12.50%, 9/72) was the major co-infecting pathogen identified followed by HRV (9.70%, 7/72). Although the viral load from children mono-infected with HAdV was slightly higher than those co-infected with HAdV and other respiratory viruses, no significant difference was seen between the two groups. The severity of HAdV infection varies according to age, socioeconomic status, environmental status and, above all, the immunological characteristics of the patient. Therefore, the etiological significance of co-infections with HAdV and other respiratory viruses and its association with disease severity require further study. It was reported HAdV can cause more severe illness in immunocompromised patients, so it would be very valuable to know about pre-existing conditions in HAdV-positive children. Except for 4 cases of asthma, there were no other comorbidities in our study. Taken together, our results provide a foundation for further clarification of the role played by HAdVs in RTIs and for defining the clinical and public health significance of HAdV infections.

Conclusions

This 1-year study documented the prevalence, age distribution, seasonality and molecular epidemiology of HAdV infections among children hospitalized with RTIs at Beiing Friendship Hospital. Our results reveal recent changes in the trends for circulating HAdV genotypes linked to RTIs in Beijing, China, which should be of value for improving the diagnosis of HAdV-related diseases and for developing new detection, treatment and prevention strategies for broad application in clinical laboratories. However, only a 956-bp region of hexon gene was sequenced for genetic analysis in the present study. Therefore, a future full-length genome analysis would help us to understand the extent of genetic variation and any potential recombination that has occurred in the strains referred to above.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article.

Abbreviations

- Ct:

-

Cycle threshold

- FluA:

-

Influenza A virus

- FluB:

-

Influenza B virus

- HAdVs:

-

Human adenoviruses

- HBoV:

-

Human bocavirus

- HCoV:

-

Human coronavirus

- HMPV:

-

Human metapneumovirus

- HRV:

-

Human rhinovirus

- Mega:

-

molecular evolutionary genetics analysis

- NPA:

-

Nasopharyngeal aspirate

- PIVs:

-

Parainfluenza viruses

- qPCR:

-

quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

- RSV:

-

Respiratory syncytial virus

- RTIs:

-

Respiratory tract infections

- SPSS:

-

Statistical product and service solutions

- WUPyV:

-

WU polyomavirus

References

Radke JR, Cook JL. Human adenovirus infections: update and consideration of mechanisms of viral persistence. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2018;31(3):251–6.

Sandkovsky U, Vargas L, Florescu DF. Adenovirus: current epidemiology and emerging approaches to prevention and treatment. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2014;16(8):416.

Hiroi S, Izumi M, Takahashi K, Morikawa S, Kase T. Isolation and characterization of a novel recombinant human adenovirus species D. J Med Microbiol. 2012;61(8):1097–102.

Prusinkiewicz MA, Mymryk JS. Metabolic reprogramming of the host cell by human adenovirus infection. Viruses. 2019;11(2):141–62.

Mei YF, Skog J, Lindman K, Wadell G. Comparative analysis of the genome organization of human adenovirus 11, a member of the human adenovirus species B, and the commonly used human adenovirus 5 vector, a member of species C. J Gen Virol. 2003;84(8):2061–71.

Chen HL, Chiou SS, Hsiao HP, Ke GM, Lin YC, Lin KH, et al. Respiratory adenoviral infections in children: a study of hospitalized cases in southern Taiwan in 2001-2002. J Trop Pediatr. 2004;50(5):279–84.

Jina L, Eunhwa C, Hoanjong L. Clinical severity of respiratory adenoviral infection by serotypes in Korean children over 17 consecutive years (1991-2007). J Clin Virol. 2010;49(2):115–20.

Jobran S, Kattan R, Shamaa J, Marzouqa H, Hindiyeh M. Adenovirus respiratory tract infections in infants: a retrospective chart-review study. Lancet. 2018;391(Suppl 2):S43.

Lion T. Adenovirus infections in immunocompetent and immunocompromised patients. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2014;27(3):441–62.

Bailey ES, Fieldhouse JK, Choi JY, Gray GC. A mini review of the zoonotic threat potential of influenza viruses, coronaviruses, adenoviruses, and enteroviruses. Front Public Health. 2018;6:104.

Zhang L, Liu W, Liu D, Chen DH, Tan WP, Qiu SY, et al. Epidemiological and clinical features of human metapneumovirus in hospitalised paediatric patients with acute respiratory illness: a cross-sectional study in southern China, from 2013 to 2016. BMJ Open. 2018;8(2):e019308.

Weinberg GA, Schnabel KC, Erdman DD, Prill MM, Iwane MK, Shelley LM, et al. Field evaluation of TaqMan Array card (TAC) for the simultaneous detection of multiple respiratory viruses in children with acute respiratory infection. J Clin Virol. 2013;57(3):254–60.

Ma FL, Li DD, Wei TL, Li JS, Zheng LS. Quantitative detection of human Malawi polyomavirus in nasopharyngeal aspirates, sera, and feces in Beijing, China, using real-time TaqMan-based PCR. Virol J. 2017;14(1):152.

Mcleish NJ, Witteveldt J, Clasper L, McIntyre C, McWilliam Leitch EC, Hardie A, et al. Development and assay of RNA transcripts of enterovirus species a to D, rhinovirus species a to C, and human parechovirus: assessment of assay sensitivity and specificity of real-time screening and typing methods. J Clin Microbiol. 2017;50(9):2910–7.

Zhang Q, Zheng WZ, Yuan WM, Ma FL, Zheng LS. Development and application of TaqMan probe real-time PCR assay for detection of KIPyV and WUPyV. Chin J Exp Clin Virol. 2015;29(3):266–9.

Lu MP, Ma LY, Zheng Q, Dong LL, Chen ZM. Clinical characteristics of adenovirus associated lower respiratory tract infection in children. World J Pediatr. 2013;9(4):346–9.

Walsh MP, Chintakuntlawar A, Robinson CM, Madisch I, Harrach B, Hudson NR, et al. Evidence of molecular evolution driven by recombination events influencing tropism in a novel human adenovirus that causes epidemic keratoconjunctivitis. PLoS One. 2009;4(6):e5653.

Liu C, Xiao Y, Zhang J, Ren L, Li J, Xie Z, et al. Adenovirus infection in children with acute lower respiratory tract infections in Beijing, China, 2007 to 2012. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:1–9.

Feng L, Li Z, Zhao S, Nair H, Lai S, Xu W, et al. Viral etiologies of hospitalized acute lower respiratory infection patients in China, 2009-2013. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e99419.

Wang H, Zheng Y, Deng J, Wang W, Liu P, Yang F, et al. Prevalence of respiratory viruses among children hospitalized from respiratory infections in Shenzhen, China. Virol J. 2016;13:1–5.

Tian JY, Hu AH, Pan JG, Liu M, Lei JL, Tang Z, et al. An outbreak of acute respiratory tract infection caused by adenovirus serotype 7 in a military camp in Shanxi province. J Pre Med Chin PLA. 2014;32(3):203–5.

Ouyang Y, Ma H, Jin M, Wang X, Wang J, Xu L, et al. Etiology and epidemiology of viral diarrhea in children under the age of five hospitalized in Tianjin, China. Arch Virol. 2012;157(5):881–7.

Li Y, Zhou W, Zhao Y, Wang Y, Xie Z, Lou Y, et al. Molecular typing and epidemiology profiles of human adenovirus infection among paediatric patients with severe acute respiratory infection in China. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0123234.

Rosete DP, Manjarrez ME, Barron BL. Adenoviruses C in non-hospitalized Mexican children older than five years of age with acute respiratory infection. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2008;103(2):195–200.

Koren MA, Arnold JC, Fairchok MP, Lalani T, Danaher PJ, Schofield CM, et al. Type-specific clinical characteristics of adenovirus-associated influenza-like illness at five US military medical centers, 2009-2014. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2016;10(5):414–20.

Demian PN, Horton KC, Kajon A, Siam R, Hasanin AM, Elgohary Sheta A, et al. Molecular identification of adenoviruses associated with respiratory infection in Egypt from 2003 to 2010. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:50.

Shimada Y, Ariga T, Tagawa Y, Aoki K, Ohno S, Ishiko H, et al. Molecular diagnosis of human adenoviruses D and E by a phylogeny-based classification method using a partial hexon sequence. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42(4):1577–84.

Ishiko H, Aoki K. Spread of epidemic keratoconjunctivitis due to a novel serotype of human adenovirus in Japan. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47(8):2678–9.

Lin MR, Yang SL, Gong YN, Kuo CC, Chiu CH, Chen CJ, et al. Clinical and molecular features of adenovirus type 2, 3, and 7 infections in children in an outbreak in Taiwan, 2011. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2017;23(2):110–6.

Wo Y, Lu QB, Huang DD, Li XK, Guo CT, Wang HY, et al. Epidemical features of HAdV-3 and HAdV-7 in pediatric pneumonia in Chongqing, China. Arch Virol. 2015;160(3):633–8.

Kim YJ, Hong JY, Lee HJ, Shin SH, Kim YK, Inada T, et al. Genome type analysis of adenovirus types 3 and 7 isolated during successive outbreaks of lower respiratory tract infections in children. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41(10):4594–9.

Moura FE, Mesquita JR, Portes SA, Ramos EA, Siqueira MM. Antigenic and genomic characterization of adenovirus associated to respiratory infections in children living in Northeast Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2007;102(8):937–41.

Lin KH, Lin YC, Chen HL, Ke GM, Chiang CJ, Hwang KP, et al. A two-decade survey of respiratory adenovirus in Taiwan: the reemergence of adenovirus types 7 and 4. J Med Virol. 2004;73(2):274–9.

La Rosa G, Muscillo M, Iaconelli M, Di Grazia A, Fontana S, Sali M, et al. Molecular characterization of human adenoviruses isolated in Italy. New Microbiol. 2006;29(3):177–84.

Glezen WP, Denny FW. Epidemiology of acute lower respiratory disease in children. N Engl J Med. 1973;288(10):498–505.

Hong JY, Lee HJ, Piedra PA, Choi EH, Park KH, Koh YY, et al. Lower respiratory tract infections due to adenovirus in hospitalized Korean children: epidemiology, clinical features, and prognosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32(10):1423–9.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Department of Pediatrics, Beijing Friendship Hospital (Capital Medical University) for providing the NPA specimens. We would also like to thank Sandra Cheesman, PhD, from Edanz Group (www.edanzediting.com/ac), for editing the English text of this manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Key Technologies R&D Program of the National Ministry of Science, China (2018ZX10713002).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LY, FM and CW performed the experiments. FM and LZ conceived and designed the experiments. FM, TW, HW and LZ analyzed the data. CW, HW and TW contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools. FM and LZ wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The project was approved by the Ethical Committee of National Institute for Viral Disease Control and Prevention, China CDC, and the committee’s reference number is 012, IVDC2018.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent for specimen collection, testing and publication was obtained from the patients’ parents or guardians.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Yao, Lh., Wang, C., Wei, Tl. et al. Human adenovirus among hospitalized children with respiratory tract infections in Beijing, China, 2017–2018. Virol J 16, 78 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12985-019-1185-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12985-019-1185-x