Abstract

Background

As countries move to malaria elimination, detecting and targeting asymptomatic malaria infections might be needed. Here, the epidemiology and detectability of asymptomatic Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax infections were investigated in different transmission settings in Ethiopia.

Method:

A total of 1093 dried blood spot (DBS) samples were collected from afebrile and apparently healthy individuals across ten study sites in Ethiopia from 2016 to 2020. Of these, 862 were from community and 231 from school based cross-sectional surveys. Malaria infection status was determined by microscopy or rapid diagnostics tests (RDT) and 18S rRNA-based nested PCR (nPCR). The annual parasite index (API) was used to classify endemicity as low (API > 0 and < 5), moderate (API ≥ 5 and < 100) and high transmission (API ≥ 100) and detectability of infections was assessed in these settings.

Results

In community surveys, the overall prevalence of asymptomatic Plasmodium infections by microscopy/RDT, nPCR and all methods combined was 12.2% (105/860), 21.6% (183/846) and 24.1% (208/862), respectively. The proportion of nPCR positive infections that was detectable by microscopy/RDT was 48.7% (73/150) for P. falciparum and 4.6% (2/44) for P. vivax. Compared to low transmission settings, the likelihood of detecting infections by microscopy/RDT was increased in moderate (Adjusted odds ratio [AOR]: 3.4; 95% confidence interval [95% CI] 1.6–7.2, P = 0.002) and high endemic settings (AOR = 5.1; 95% CI 2.6–9.9, P < 0.001). After adjustment for site and correlation between observations from the same survey, the likelihood of detecting asymptomatic infections by microscopy/RDT (AOR per year increase = 0.95, 95% CI 0.9–1.0, P = 0.013) declined with age.

Conclusions

Conventional diagnostics missed nearly half of the asymptomatic Plasmodium reservoir detected by nPCR. The detectability of infections was particularly low in older age groups and low transmission settings. These findings highlight the need for sensitive diagnostic tools to detect the entire parasite reservoir and potential infection transmitters.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Following considerable successes in the control of malaria in the last two decades, progress plateaued or stalled in many settings in Africa [1]. Ethiopia runs a successful malaria control programme [2] that makes it one of the four countries (together with India, Rwanda, and Pakistan) that continues to maintain the declining trend in malaria burden [3]. As a result, the country is on track for a 40% reduction in incidence (together with Rwanda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe) and malaria mortality rates (together with Zambia) by 2020 [1]. To guide elimination efforts that currently targets 239 selected districts, the National Malaria Control Programme (NMCP) of Ethiopia stratified the country into four strata using district level annual parasite index (API) data from 2017 [4] as malaria-free (API, 0), low (API, 0–5), moderate (API, 5–100), and high (API, ≥ 100) [4]. Despite its value, the adopted stratification lacks granularity and is not able to capture relevant spatial and temporal heterogeneities in low endemic settings [5, 6]. The unique epidemiology of malaria transmission in Ethiopia; the presence of strictly seasonal transmission in some settings and perennial transmission elsewhere, as well as different levels of co-endemicity of Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax [2], calls for the use of tailored approaches to characterize the epidemiology of malaria.

District level stratification that relies on malaria incidence data has limitations in settings where case numbers are extremely low. Incidence data are also sensitive to changes in care seeking behavior, rates of testing of suspected cases, and reporting completeness [7]. Screening approaches to determine the prevalence of (often asymptomatic) infections that are present in communities have great potential to define transmission intensity [8]. However, parasite prevalence estimates are greatly affected by parasite density distributions in communities that determine the detectability of infections by different diagnostics. Malaria elimination efforts may benefit from targeting all infections present in communities, irrespective of clinical presentation [9,10,11]. There is a growing body of evidence on the public health importance of asymptomatic malaria infections and their contribution to onwards malaria transmission in high [12, 13] and low transmission settings [13, 14]. Importantly, most asymptomatic infections detected in community surveys are of low parasite density and the proportion of all infections that are submicroscopic varies between settings [15]. Previous studies in Ethiopia detected a significant burden of asymptomatic P. falciparum and P. vivax infections [16,17,18,19]. These studies used different diagnostic techniques and sampling designs, making it difficult to compare parasite prevalence estimates or diagnostic performance indicators across settings. The aim of the present study was to understand the epidemiology of asymptomatic Plasmodium infections in different settings in Ethiopia and their detectability by microscopy, rapid diagnostics test (RDT) and molecular methods.

Methods and materials

Study areas

The study was conducted in ten districts (woredas) encompassing different transmission settings (Fig. 1). Malaria transmission is highly heterogeneous in Ethiopia and transmission intensity varies spatially and temporally [20]. Study sites representing low (n = 2), moderate (n = 4), and high (n = 4) transmission settings as per the national stratification were selected from five administrative regions (Fig. 1). Low transmission settings include Gomma and Babile districts from Oromia region. Moderate transmission settings include Bahir Dar Zuria and North Achefer districts from Amhara region and Arba Minch Zuria from the Southern region and Mao Komo from Benishangul region. High transmission districts were from Gambela (Lare and Abobo), Amhara (Jawi), and Benishangul (Meng) regions.

Study population and sample collection

Samples were collected in community and school-based cross-sectional surveys from 2016 to 2020. Specifically, community-based surveys were conducted at Abobo, Lare, Mao-komo, Menge, and Gomma districts in 2016, Babile district in 2018, and Arba Minch Zuria district in 2020. School based surveys were conducted at North Achefer, Bahir Dar Zuria, and Jawi districts in 2017. For the school-based surveys, students were randomly selected from elementary school students stratified by age as described before [21] following protocols developed by Brooker and colleagues [22].

Prior to recruitment of participants for community surveys, sensitization was undertaken by teams that involve study team members, village-based health extension workers, malaria focal person of the district, local administrators, and elderly. The study purpose, procedure, risk, and benefit were explained in local language. After this first step, volunteer community members were invited to join the study upon obtaining informed written consent and enrolled in the study on first come, first served basis.

Finger prick blood samples (~ 300 µL) collected from all participants were used to diagnose malaria using RDT (First Response® malaria Antigen pLDH/HRP2 P.f and Pan Combo Card Test, Premier Medical Corporation Ltd, Dist. Valsad, India) or thin and thick blood films, and to prepare dried blood spots (DBS) on 3MM Whatman filter papers (Whatman, Maidstone, UK). Malaria was diagnosed using RDT at Abobo, Lare, Mao-Komo, Menge, and Gomma districts whilst microscopy was used at the school surveys, Arba Minch Zuria and Babile districts. Detailed clinical and socio-demographic data were captured using a pretested semi-structured interview-based questionnaire. Axillary body temperature was measured for all participants. If a participant was found febrile (axillary temperature ≥ 37.5 °C) or reports history of fever in the past 48 h, malaria status was checked using RDT and treated immediately when found positive following the national treatment guideline [23]. DBS were air dried, protected from direct sunlight, and enclosed in zip locked plastic bags individually with self-indicating silica gel (Loba Chemie, Mumbai, India). Samples were transported at ambient temperature and stored at − 20 °C until further use. Giemsa-stained thick and thin smears were read independently by two experienced malaria microscopists. A third expert microscopist was consulted in case of discordant results. Thick smear slides were declared negative if no parasites were detected after observing 100 fields under oil immersion (100× magnification).

Species specific detection of Plasmodium parasites by 18S rRNA based nested polymerase chain reaction

Genomic DNA was extracted from 6 mm diameter DBS punches using Chelex-Saponin extraction method [24]. In brief, DNA was eluted after an overnight lysis in 0.5% saponin (SIGMA)/PBS (SIGMA) buffer and washing step followed by boiling at 97 ˚C in 150 µL of 6% Chelex (Bio Rad) in DNase/RNase free water (SIGMA). From the final eluate, 80 µL was transferred into a new plate and stored at − 20 ˚C until further use. Plasmodium species identification was done by nested polymerase chain reaction (nPCR) that targeted the small subunit 18S rRNA gene as described before [25]. A positive control (for P. falciparum NF54 culture from Radboudumc, Nijmegen, The Netherlands; for P. vivax the malaria reference laboratory positive controls from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, UK) and negative controls (PCR grade water) were run in every reaction plate. Amplified products were visualized using UV transilluminator (Bio Rad, USA) after electrophoresis using 2% agarose gels (SIGMA, ALDRICH) stained with Ethidium Bromide (Promega, Madison, USA).

Statistical analysis

For the school surveys, sample size was calculated based on protocols by Brooker and colleagues [22] for the original study that aimed at assessing longitudinal evaluation of parasite prevalence in school children [21]. For this study, 70.0% (231/330) of the students were successfully sampled. For the community surveys, an overall prevalence of 6.8% asymptomatic Plasmodium infections was expected based on previous observations [17, 19, 26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35] with a precision of 5%. Based on previous experience, a minimum of 75 samples for the school surveys and 114 for the community samples was targeted across the study sites [21]. Data was double entered into excel, compiled, checked for consistency, and analyzed using Stata version 15 (Stata corporation; College Station, TX, USA) and GraphPad Prism 5.3 (GraphPad Software Inc., CA, USA). Proportions were compared between categories using Fisher’s exact test and Pearson’s chi-squared test where it was appropriate. Equality tests on unmatched data such as age between school and community surveys were tested by two-sample Wilcoxon rank-sum (Mann-Whitney) test. Generalized Estimating Equation (GEE) was used to allow parameter estimates and standard errors adjusted for clustering across the study sites; exchangeable correlation matrix and robust standard errors were used. Sample characteristics such as age, gender, and transmission intensity were tested in the model for their association with infection prevalence and roles as potential confounders. A 5% level of significance was considered in all cases.

Results

Characteristics of study participants

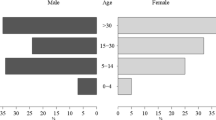

A total of 1093 individuals, 231 from school (3 schools; 75–80 per school survey) and 862 from community surveys (7 surveys; 114–161 per study site) participated in the study. None of the partifcipants was febrile at the time of sampling. Female participants constituted 43.5% (372/855) of community and 51.8% (118/228) of school surveys (P = 0.026). The overall median age of the participants was 16 years (Interquartile range [IQR]: 11–35). As expected, participants from the school surveys were younger (median age, 12; IQR, 11–14) than community surveys (median age, 23; IQR, 10–38; P < 0.001). Results are presented separately for community and school surveys, focusing on community surveys for the main comparisons (Table 1). Within the community surveys, participants from low (median age, 30; IQR, 18–45; n = 232) and moderate (median age, 30; IQR, 12–42; n = 272) endemic settings were older than participants from high endemic settings (median age, 13; IQR, 8–28; n = 318; P < 0.001).

Prevalence of asymptomatic malaria infection across the study sites

In the community surveys, the overall prevalence of asymptomatic Plasmodium infections was 12.2% (105/860) by microscopy/RDT and 21.6% (183/846) by nPCR (Table 1); 24.1% (208/862) of participants were parasite positive by either nPCR and/or microscopy/RDT. When considering infecting Plasmodium species by nPCR, 16.4% (139/846) of samples were P. falciparum positive; 3.7% (31/846) were P. vivax and 1.5% (13/846) were mixed P. vivax and P. falciparum. Although the school surveys were from high and moderate transmission sites, there was overall lower Plasmodium infection prevalence in the school surveys than in the community surveys as measured by all methods combined (11.3% vs. 24.1%; χ2 = 17.9, P < 0.001).

Among the school surveys, the overall prevalence of asymptomatic malaria was 0.4% (1/231) by microscopy/RDT whilst 11.3% (26/231) were parasite positive either by nPCR or both methods combined. Of these nPCR positive malaria infections from the school surveys, 2.6% (6/231) were due to P. falciparum, 5.2% (12/231) were due to P. vivax, and 3.5% (8/231) were due to mixed P. falciparum and P. vivax species infections (Additional file 1: Table S1, Additional file 2: Table S2).

Across the community surveys, in high transmission settings, nPCR-based prevalence of malaria infection ranged from 17.6% (n/N) at Meng to 46.1% (47/102) at Lare district. In the moderate transmission sites, the nPCR-based prevalence was 29.3% (34/116) at Mao-Komo and 12.4% (20/161) at Arbaminch Zuria district. In low transmission sites, the overall nPCR infection prevalence was 9.4% (22/234). The overall microscopy/RDT based prevalence was 23.1% (81/351), 7.9% (22/277), and 0.9% (2/232), in high, moderate, and low transmission settings, respectively (Table 1).

Among the community samples, the prevalence of Plasmodium infections detected by all methods combined was substantially higher for the high transmission settings (36.7%, 129/351; 95% CI 31.9–41.9; P < 0.001) compared to moderate (20.6%, 57/277; 95% CI 16.2–25.8) and low transmission settings (9.4%, 22/234; 95% CI 6.3–13.9). Moreover, the burden of asymptomatic Plasmodium infection was higher in the 5–15 age groups as measured by microscopy/RDT (20.7%, 50/241, P < 0.001) and nPCR (26.7%, 62/232, P = 0.008) (Table 1) as compared to under-five children and adults older than 15 years (Table 1).

Detectability of asymptomatic Plasmodium infections in different endemicities

Among community samples, microscopy/RDT detected 44.2% (80/181) of nPCR detected Plasmodium infections (Agreement = 86.9%, κ = 0.526, Table 2). All, but 8 RDT positive P. falciparum and 1 microscopy positive P. vivax sample, were also nPCR positive (Additional file 2: Table S2). The likelihood that Plasmodium infected individuals (i.e. individuals who were parasite positive by any diagnostic method) were detected by RDT was increased for individuals living in higher transmission settings (AOR = 5.1, 95% CI 2.6–9.9, P < 0.001) and individuals living in moderate transmission (AOR: 3.4, 95% CI 1.6–7.2, P = 0.002) compared to low transmission settings (Additional file 3: Table S3; Fig. 2). Age was an important predictor of asymptomatic malaria positivity by microscopy/RDT. After adjusting for site and correlation between observations from the same survey, a 5% decline in detection using microscopy/RDT was observed for every year increase of age from those that tested positive by all methods (AOR = 0.95, 95% CI 0.9–1.0, P = 0.013).

Community and school- based surveys asymptomatic malaria infection prevalence and detectability using nPCR and microscopy/RDT: black circles represent parasite prevalence by nPCR (x-axis) and proportion all infections detected by microscopy/RDT (left y-axis); white circles indicate parasite prevalence by microscopy/RDT (right y-axis). School surveys were (N. Achefer) North Achefer, BDZ (Bahir Dar Zuria) and Jawi

The parasite species composition and detectability varied between transmission settings (Fig. 2). Among the Plasmodium species detected in the community samples, the majority were attributable to P. falciparum (77.4%, 161/208) when all samples were combined. Of the nPCR detected P. falciparum-mono species infections (n = 139) and mixed-species infections (n = 13), microscopy/RDT successfully detected P. falciparum in 48.7% (73/150) of infections (Table 2). Of the nPCR detected P. vivax-mono infections (n = 31) and mixed-species infections (n = 13), microscopy/RDT successfully detected P. vivax in 4.6% (2/44) of infections (Table 2).

Discussion

This study describes the prevalence and detectability of asymptomatic Plasmodium infections in ten different transmission settings by nPCR and conventional diagnostics (i.e. microscopy/RDT). More asymptomatic infections were detected in high transmission settings by both methods. The detectability of asymptomatic Plasmodium infections using microscopy/RDT relative to nPCR increased as transmission intensity increases. As a result, most infections in low transmission settings were not detectable by microscopy/RDT.

In Ethiopia, several cross-sectional studies have documented asymptomatic parasite carriage using conventional and molecular methods [16,17,18, 33, 34]. The current multi-site study allowed an assessment of factors influencing the prevalence of infections as well as their detectability by microscopy-RDT. The prevalence of asymptomatic Plasmodium infections in the current study was in the same range as other reports from high [18, 34] and moderate [27] transmission settings in Ethiopia and elsewhere [17, 29, 36, 37].

Consistent with other studies [16, 38, 39], the current study observed that microscopy/RDT detected fewer asymptomatic infections as compared to PCR. The proportion of Plasmodium infections that was detectable by microscopy/RDT increased with increasing in transmission intensity. Whilst this trend has been reported in meta-analyses for P. falciparum [15, 36, 40], it is striking that this trend is also apparent in the current study within one country affected by both P. falciparum and P. vivax. Moreover, the effect size was comparatively large with approximately 5-fold higher detectability of infections in high endemic settings compared to low endemic settings. The trend of increasing detectability with increasing transmission intensity may be attributable to the fact that asymptomatically infected individuals have higher average parasite densities in high transmission settings [15, 41]. Moreover, in low endemic settings individuals will receive fewer infectious bites with, due to the absence of super-infections, lower parasitemia over the course of infection [9, 36]. Low genetic diversity of the parasite population in low transmission settings may also contribute to rapidly acquired immunity to the specific clones [42], further limiting parasite density. An impact of immunity on parasite density and the detectability of infections is also illustrated by the negative impact of increasing age on the detectability on infections in line with the current study [43].

Lower parasite densities in P. vivax compared to P. falciparum [44, 45] also results in a low detectability of P. vivax infections by microscopy/RDT. This low density in P. vivax is mainly attributable to the parasite’s preference to infect reticulocytes [46, 47] that typically constitute less than 1% of the total erythrocyte population [48] and also to the early acquisition of immunity [47]. These findings have implications for estimates of the relative burden of P. falciparum and P. vivax infections. The introduction of sensitive molecular tools may thus improve the detection of P. vivax infections substantially. Since treatment strategies differ for P. falciparum and P. vivax, this is relevant for public health interventions.

Although RDT and microscopy were used separately in the study sites due to logistics reasons, the prevalence measured by conventional RDT and microscopy was assumed to be comparable [37].

Nine samples that were declared microscopy/RDT positive were negative by nPCR while seven samples that were detected P. falciparum positive by RDT were P. vivax positive by nPCR. False RDT positivity might be due to the presence of parasite antigens after adequate clearance of parasites which might explain the variation between RDT positivity and PCR negative detection among asymptomatic malaria infections [49, 50]. Hence, there is a possibility that RDT can be positive for lingering antigens of P. falciparum while missing the low-density P. vivax infection from the same patient.

Conclusions

Conventional diagnostics missed nearly half of the asymptomatic malaria reservoir detected by nPCR. Moreover, the detectability of asymptomatic Plasmodium infections in all endemic sites might reflect the long persistence of these infections from weeks up to months in high [51] as well as in low transmission settings [52, 53] even in the presence of effective control and elimination interventions. As these infections can have relevance for onward malaria transmission [13,14,15], a detailed understanding of the distribution, detectability, and contribution to the infectious reservoir of asymptomatic infections will greatly improve our ability to target all relevant infections. The wide scale presence of low-density infections calls for more in-depth studies on understanding parasite density oscillations, their relevance for malaria symptoms, and onward transmission to mosquitoes.

References

WHO. World malaria report 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2019. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/world-malaria-report-2019. Accessed 17 June 2020.

Taffese HS, Hemming-Schroeder E, Koepfli C, Tesfaye G, Lee M-c, Kazura J, Yan G-Y, Zhou G-F. Malaria epidemiology and interventions in Ethiopia from 2001 to 2016. Infect Dis Poverty. 2018;7:1–9.

WHO. World malaria report 2018. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2018. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/275867/9789241565653-eng.pdf?ua=1. Accessed 07 Nov 2018.

PMI. Malaria Operational Plan FY 2019. Addis Ababa: President's Malaria Initiative. 2019. https://www.pmi.gov/docs/default-source/default-document-library/malaria-operational-plans/fy19/fy-2019-ethiopia-malaria-operational-plan.pdf?sfvrsn=3. Accessed 13 Mar 2020.

Clements AC, Barnett AG, Cheng ZW, Snow RW, Zhou HN. Space-time variation of malaria incidence in Yunnan province, China. Malar J. 2009;8(1):180.

Mwesigwa J, Achan J, Di Tanna GL, Affara M, Jawara M, Worwui A, Hamid-Adiamoh M, Kanuteh F, Ceesay S, Bousema T. Residual malaria transmission dynamics varies across The Gambia despite high coverage of control interventions. PLoS One. 2017;12(11):e0187059.

Thwing J, Camara A, Candrinho B, Zulliger R, Colborn J, Painter J, Plucinski MM. A robust estimator of malaria incidence from routine health facility data. Am J Tropical Med Hyg. 2020;102(4):811–20.

Weiss DJ, Lucas TC, Nguyen M, Nandi AK, Bisanzio D, Battle KE, Cameron E, Twohig KA, Pfeffer DA, Rozier JA. Mapping the global prevalence, incidence, and mortality of Plasmodium falciparum, 2000–17: a spatial and temporal modelling study. Lancet. 2019;394(10195):322–31.

Bousema T, Okell L, Felger I, Drakeley C. Asymptomatic malaria infections: detectability, transmissibility and public health relevance. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2014;12(12):833–40.

Cheaveau J, Mogollon DC, Mohon MAN, Golassa L, Yewhalaw D, Pillai DR. Asymptomatic malaria in the clinical and public health context. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2019;17(12):997–1010.

Whittaker C, Slater HC, Bousema T, Drakeley C, Ghani A, Okell LC. Variation in the Prevalence of Submicroscopic Malaria Infections: Historical Transmission Intensity and Age as Key Determinants. bioRxiv. 2019:554311.

Ouedraogo AL, Goncalves BP, Gneme A, Wenger EA, Guelbeogo MW, Ouedraogo A, Gerardin J, Bever CA, Lyons H, Pitroipa X, et al. Dynamics of the Human Infectious Reservoir for Malaria Determined by Mosquito Feeding Assays and Ultrasensitive Malaria Diagnosis in Burkina Faso. J Infect Dis. 2016;213(1):90–9.

Gonçalves BP, Kapulu MC, Sawa P, Guelbéogo WM, Tiono AB, Grignard L, Stone W, Hellewell J, Lanke K, Bastiaens GJH, et al. Examining the human infectious reservoir for Plasmodium falciparum malaria in areas of differing transmission intensity. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1):1133.

Tadesse FG, Slater HC, Chali W, Teelen K, Lanke K, Belachew M, Menberu T, Shumie G, Shitaye G, Okell LC, et al. The relative contribution of symptomatic and asymptomatic Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium falciparum infections to the infectious reservoir in a low-endemic setting in Ethiopia. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66(12):1883–91.

Slater HC, Ross A, Felger I, Hofmann NE, Robinson L, Cook J, Goncalves BP, Bjorkman A, Ouedraogo AL, Morris U, et al. The temporal dynamics and infectiousness of subpatent Plasmodium falciparum infections in relation to parasite density. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):1433.

Tadesse FG, Pett H, Baidjoe A, Lanke K, Grignard L, Sutherland C, Hall T, Drakeley C, Bousema T, Mamo H. Submicroscopic carriage of Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax in a low endemic area in Ethiopia where no parasitaemia was detected by microscopy or rapid diagnostic test. Malar J. 2015;14:303.

Zhou G, Yewhalaw D, Lo E, Zhong D, Wang X, Degefa T, Zemene E, Lee M-c, Kebede E, Tushune K, Yan G. Analysis of asymptomatic and clinical malaria in urban and suburban settings of southwestern Ethiopia in the context of sustaining malaria control and approaching elimination. Malar J. 2016;15(1):1–9.

Assefa A, Ahmed AA, Deressa W, Wilson GG, Kebede A, Mohammed H, Sassine M, Haile M, Dilu D, Teka H. Assessment of subpatent Plasmodium infection in northwestern Ethiopia. Malar J. 2020;19:1–10.

Golassa L, Enweji N, Erko B, Aseffa A, Swedberg G. Detection of a substantial number of sub-microscopic Plasmodium falciparum infections by polymerase chain reaction: a potential threat to malaria control and diagnosis in Ethiopia. Malar J. 2013;12:8.

EPHI. EMIS: Ethiopian National Malaria indicator Survey 2015. Addis Ababa: Ethiopian Public Health Institute. 2016. https://malariasurveys.org/documents/Ethiopia_MIS_2015.pdf. Accessed 25 Dec 2020.

Tadesse FG, Hoogen L, Lanke K, Schildkraut J, Tetteh K, Aseffa A, Mamo H, Sauerwein R, Felger I, Drakeley C. The shape of the iceberg: quantification of submicroscopic Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax parasitaemia and gametocytaemia in five low endemic settings in Ethiopia. Malar J. 2017;16(1):99.

Brooker S, Kolaczinski JH, Gitonga CW, Noor AM, Snow RW. The use of schools for malaria surveillance and programme evaluation in Africa. Malar J. 2009;8(1):231.

PMI. Malaria Operational Plan FY 2018. Addis Ababa: President's Malaria Initiative. 2018. https://www.pmi.gov/docs/default-source/default-document-library/malaria-operational-plans/fy-2018/fy-2018-ethiopia-malaria-operational-plan.pdf?sfvrsn=5. Accessed 05 Jan 2021.

Baidjoe A, Stone W, Ploemen I, Shagari S, Grignard L, Osoti V, Makori E, Stevenson J, Kariuki S, Sutherland C. Combined DNA extraction and antibody elution from filter papers for the assessment of malaria transmission intensity in epidemiological studies. Malar J. 2013;12(1):272.

Snounou G, Viriyakosol S, Zhu XP, Jarra W, Pinheiro L, do Rosario VE, Thaithong S, Brown KN. High sensitivity of detection of human malaria parasites by the use of nested polymerase chain reaction. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1993;61(2):315–20.

Adebo SM, Eckerle JK, Andrews ME, Howard CR, John CC. Asymptomatic Malaria and Other Infections in Children Adopted from Ethiopia, United States, 2006–2011. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21(7):1227–9.

Alemu G, Mama M. Assessing ABO/Rh blood group frequency and association with asymptomatic malaria among blood donors attending Arba Minch blood bank, South Ethiopia. Malar Res Treat. 2016;2016:8043768.

Fekadu M, Yenit MK, Lakew AM. The prevalence of asymptomatic malaria parasitemia and associated factors among adults in Dembia district, northwest Ethiopia, 2017. Arch Public Health. 2018;76(1):74.

Nega D, Dana D, Tefera T, Eshetu T. Prevalence and predictors of asymptomatic malaria parasitemia among pregnant women in the rural surroundings of Arbaminch Town, South Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0123630.

Worku L, Damtie D, Endris M, Getie S, Aemero M. Asymptomatic Malaria and Associated Risk Factors among School Children in Sanja Town. Northwest Ethiopia Int Sch Res Notices. 2014;2014:303269.

Aschale Y, Mengist A, Bitew A, Kassie B, Talie A. Prevalence of malaria and associated risk factors among asymptomatic migrant laborers in West Armachiho District, Northwest Ethiopia. Res Rep Trop Med. 2018;9:95–101.

Lo E, Yewhalaw D, Zhong D, Zemene E, Degefa T, Tushune K, Ha M, Lee MC, James AA, Yan G. Molecular epidemiology of Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium falciparum malaria among Duffy-positive and Duffy-negative populations in Ethiopia. Malar J. 2015;14:84.

Golassa L, Baliraine FN, Enweji N, Erko B, Swedberg G, Aseffa A. Microscopic and molecular evidence of the presence of asymptomatic Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax infections in an area with low, seasonal and unstable malaria transmission in Ethiopia. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:310.

Girma S, Cheaveau J, Mohon AN, Marasinghe D, Legese R, Balasingam N, Abera A, Feleke SM, Golassa L, Pillai DR. Prevalence and epidemiological characteristics of asymptomatic malaria based on ultrasensitive diagnostics: a cross-sectional study. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;69(6):1003–10.

Santana-Morales MA, Afonso-Lehmann RN, Quispe MA, Reyes F, Berzosa P, Benito A, Valladares B, Martinez-Carretero E. Microscopy and molecular biology for the diagnosis and evaluation of malaria in a hospital in a rural area of Ethiopia. Malar J. 2012;11:199.

Okell LC, Bousema T, Griffin JT, Ouédraogo AL, Ghani AC, Drakeley CJ. Factors determining the occurrence of submicroscopic malaria infections and their relevance for control. Nat commun. 2012;3:1237.

Wu L, van den Hoogen LL, Slater H, Walker PGT, Ghani AC, Drakeley CJ, Okell LC. Comparison of diagnostics for the detection of asymptomatic Plasmodium falciparum infections to inform control and elimination strategies. Nature. 2015;528:86–93.

Idris ZM, Chan CW, Kongere J, Gitaka J, Logedi J, Omar A, Obonyo C, Machini BK, Isozumi R, Teramoto I. High and heterogeneous prevalence of asymptomatic and sub-microscopic malaria infections on islands in Lake Victoria, Kenya. Sci Rep. 2016;6:36958.

Berzosa P, de Lucio A, Romay-Barja M, Herrador Z, González V, García L, Fernández-Martínez A, Santana-Morales M, Ncogo P, Valladares B. Comparison of three diagnostic methods (microscopy, RDT, and PCR) for the detection of malaria parasites in representative samples from Equatorial Guinea. Malar J. 2018;17:333.

Whittaker C, Slater H, Bousema T, Drakeley C, Ghani A, Okell L: Global & Temporal Patterns of Submicroscopic Plasmodium falciparum Malaria Infection. bioRxiv. 2020:554311.

Sattabongkot J, Suansomjit C, Nguitragool W, Sirichaisinthop J, Warit S, Tiensuwan M, Buates S. Prevalence of asymptomatic Plasmodium infections with sub-microscopic parasite densities in the northwestern border of Thailand: a potential threat to malaria elimination. Malar J. 2018;17(1):329.

Clark EH, Silva CJ, Weiss GE, Li S, Padilla C, Crompton PD, Hernandez JN, Branch OH. Plasmodium falciparum malaria in the Peruvian Amazon, a region of low transmission, is associated with immunologic memory. Infect Immun. 2012;80:1583–92.

Proietti C, Pettinato DD, Kanoi BN, Ntege E, Crisanti A, Riley EM, Egwang TG, Drakeley C, Bousema T. Continuing intense malaria transmission in northern Uganda. Am J Tropical Med Hyg. 2011;84(5):830–7.

Koepfli C, Robinson LJ, Rarau P, Salib M, Sambale N, Wampfler R, Betuela I, Nuitragool W, Barry AE, Siba P, et al. Blood-stage parasitaemia and age determine Plasmodium falciparum and P. vivax gametocytaemia in Papua New Guinea. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0126747.

Hofmann NE, Karl S, Wampfler R, Kiniboro B, Teliki A, Iga J, Waltmann A, Betuela I, Felger I, Robinson LJ, Mueller I. The complex relationship of exposure to new Plasmodium infections and incidence of clinical malaria in Papua New Guinea. eLife. 2017;6:e23708.

Lim C, Pereira L, Saliba KS, Mascarenhas A, Maki JN, Chery L, Gomes E, Rathod PK, Duraisingh MT. Reticulocyte Preference and Stage Development of Plasmodium vivax Isolates. J Infect Dis. 2016;214(7):1081–4.

Moreno-Pérez DA, Ruíz JA, Patarroyo MA. Reticulocytes: Plasmodium vivax target cells. Biol Cell. 2013;105(6):251–60.

Koepke JF, Koepke JA. Reticulocytes. Clin Lab Haemat. 1986;8(3):169–79.

Bell DR, Wilson DW, Martin LB. False-positive results of a Plasmodium falciparum histidine-rich protein 2–detecting malaria rapid diagnostic test due to high sensitivity in a community with fluctuating low parasite density. Am J Tropical Med Hyg. 2005;73(1):199–203.

Dalrymple U, Arambepola R, Gething PW, Cameron E. How long do rapid diagnostic tests remain positive after anti-malarial treatment? Malar J. 2018;17(1):228.

Males S, Gaye O, Garcia A. Long-term asymptomatic carriage of Plasmodium falciparum protects from malaria attacks: a prospective study among Senegalese children. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46(4):516–22.

Nguyen T-N, von Seidlein L, Nguyen T-V, Truong P-N, Hung SD, Pham H-T, Nguyen T-U, Le TD, Dao VH, Mukaka M, et al. The persistence and oscillations of submicroscopic Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax infections over time in Vietnam: an open cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18(5):565–72.

Tripura R, Peto TJ, Chalk J, Lee SJ, Sirithiranont P, Nguon C, Dhorda M, von Seidlein L, Maude RJ, Day NPJ, et al. Persistent Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax infections in a western Cambodian population: implications for prevention, treatment and elimination strategies. Malar J. 2016;15(1):181.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the study participants for their willingness and local facilitators of the study sites for their support during the sample collection. We also thank the WHO certified microscopists (Tewabech Lema and Tsehay Orlando) at Adama Malaria Center for their support. We appreciate the regional and district health officers for their collaboration. The malaria team members and researchers at AHRI (Tizita Tsegaye, Tadele Emiru, Temesgen Tafesse, Mikiyas Gebremichael, Misgana Muluneh, Endashaw Esayas, Tsegaye Hailu, Haile Abera, Demekech Damte, Tiruwork Fanta, Senya Asfer, and Eyuel Asemahegn) played an important role in making the study successful. We are indebted to the drivers of AHRI for their support during the field sample collection.

Funding

The study was supported by the Armauer Hansen Research Institute (via its core funding from Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation and Swedish International Development Cooperation); the Netherlands organization for international cooperation in higher education (Nuffic) [Grant number NFP-PhD.14/150] to FGT; the European Research Council [ERC-2014-StG 639776] to TB; the Bill & Melinda Gates foundation [INDIE; OP P1173572] to TB, FGT and CD. The funders have no role in the in the design of the study, collection, analysis, interpretation of the data and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FGT, EH, EG, CD and TB conceived the study, contributed to data analysis and critically commented on the manuscript. EH analyzed the data. EH and SKT drafted the manuscript. EH, SK, WC, GS and MK conducted the laboratory study. WC, MK, EH, SKT, AG, GS, TA collected blood samples. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical statement

The study protocol was approved by the Ethiopian National Research Ethics Review Committee (3.10/016/20), and the institutional ethics review boards of the Department of Biochemistry (Ref.No.SOM/DRERC/BCH005/2009) and the College of Natural Sciences (Ref.No. SOM/DRERC/BCH005/2009) at Addis Ababa University, and the Armauer Hansen Research Institute (P035/17, P024/17 and P032/18).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declared that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1.

School based prevalence of asymptomatic malaria in selected sites from different transmission settings using nPCR and microscopy/RDT from 2016 to 2018, Ethiopia.

Additional file 2: Table S2.

Concordance of RDT and Microscopy detected samples compared to nPCR among the study participants, 2016–2020.

Additional file 3: Table S3.

GEE model for association of malaria infection prevalence using all methods combined (nPCR and/or microscopy/RDT) among community survey samples with sample characteristics such as gender, age category, level of endemicity from 2016 to 2020, Ethiopia.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Hailemeskel, E., Tebeje, S.K., Behaksra, S.W. et al. The epidemiology and detectability of asymptomatic Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium falciparum infections in low, moderate and high transmission settings in Ethiopia. Malar J 20, 59 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-021-03587-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-021-03587-4