Abstract

Background

Poor communication skills can potentially compromise patient care. However, as communication skills training (CST) programs are not seen as a priority to many clinical departments, there is a discernible absence of a standardised, recommended framework for these programs to be built upon. This systematic scoping review (SSR) aims to gather prevailing data on existing CSTs to identify key factors in teaching and assessing communication skills in the postgraduate medical setting.

Methods

Independent searches across seven bibliographic databases (PubMed, PsycINFO, EMBASE, ERIC, CINAHL, Scopus and Google Scholar) were carried out. Krishna’s Systematic Evidence-Based Approach (SEBA) was used to guide concurrent thematic and content analysis of the data. The themes and categories identified were compared and combined where possible in keeping with this approach and then compared with the tabulated summaries of the included articles.

Results

Twenty-five thousand eight hundred ninety-four abstracts were identified, and 151 articles were included and analysed. The Split Approach revealed similar categories and themes: curriculum design, teaching methods, curriculum content, assessment methods, integration into curriculum, and facilitators and barriers to CST.

Amidst a wide variety of curricula designs, efforts to develop the requisite knowledge, skills and attitudes set out by the ACGME current teaching and assessment methods in CST maybe categorised into didactic and interactive methods and assessed along Kirkpatrick’s Four Levels of Learning Evaluation.

Conclusions

A major flaw in existing CSTs is a lack of curriculum structure, focus and standardisation. Based upon the findings and current design principles identified in this SSR in SEBA, we forward a stepwise approach to designing CST programs. These involve 1) defining goals and learning objectives, 2) identifying target population and ideal characteristics, 3) determining curriculum structure, 4) ensuring adequate resources and mitigating barriers, 5) determining curriculum content, and 6) assessing learners and adopting quality improvement processes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Effective doctor-patient communication boosts patient safety and the patient experience [1, 2]. It also improves treatment adherence and reduces malpractice suits and burnout amongst physicians [3, 4]. Whilst the General Medical Council, CanMEDS and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) [5,6,7,8] regard communication skills as a core competency, efforts to advance communication skills training (CST) in medical schools and residency programs remain poorly coordinated [9,10,11,12,13,14] and, perhaps more concerning, still tethered to the belief that good communications can be learnt ‘on the job’ [15].

With there being a wide array of skills to be mastered, including being able to gather information [15], consider the patient’s circumstances and needs, adapt communication styles and content, facilitate open and respectful discussions and shared decision making, negotiate a personalised patient-centred treatment plan, give therapeutic instructions in an empathetic and understandable manner and establish a caring, responsive doctor-patient relationship, the need for a structured CST program for medical students and physicians is evident [16, 17]. In addition, amidst suggestions that communications skills degrade over time, a longitudinal CST program that melds training, clinical experience, assessments, and reflective practice supported by role modelling, coaching and mentoring is critical [18, 19]. Such a longitudinal approach would be consistent with Hoffman et al. [20]‘s recommendation aimed at developing adaptive clinical communication skills that are responsive to the needs of different patients in different circumstances.

However, facing the recalcitrant notion in some quarters that good communications skills are a “an easy and soft science … not worth studying” [21], design and operationalising longitudinal CST programs face significant obstacles. We believe an evidence-based review of prevailing practices and outcomes will be useful in addressing these misconceptions and will help to facilitate the reshaping of attitudes and thinking towards CST.

Rationale for this review

Acknowledging growing evidence of the impact of CST in medical schools and the influence of different healthcare and education systems, practice settings and practical considerations [22] on the structure and content of CST programs, we focus on better understanding current approaches to CST in the postgraduate setting. The lessons learnt will inform efforts to advance an evidence-based framework for a CST curriculum that may be applied in different countries, and sociocultural settings.

Methodology

A systematic scoping review (SSR) is proposed to map prevailing practice and clarify concepts, definitions and key characteristics of CST practice in the extant literature so as to guide design of an evidence-based CST program [23,24,25,26,27,28,29]. An SSR is also able to identify gaps in prevailing knowledge on CSTs [30, 31]. Rooted in Constructivist ontology and Relativist epistemology, SSRs are well suited for considering the effects of clinical, academic, personal, research, professional, ethical, psychosocial, emotional, legal, and educational settings and learning environment upon CST processes [32,33,34,35,36,37,38]. Here, a Relativist lens captures the impact of the learner’s various CST training experiences which Positivist and Post-Positivist approaches fail to consider. However, whilst these considerations present SSRs as the preferred approach to scrutinising the width, depth, and longitudinal effects of CST, SSRs continue to suffer from a lack of a structured approach that compromises its trustworthiness and reproducibility.

To overcome these problems facing SSRs, we adopt Krishna’s Systematic Evidence-Based Approach (SEBA) (henceforth SSR in SEBA) [31, 39, 40]. SSRs in SEBA are shown to be well suited to review various aspects of medical education [23, 24, 41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53]. By employing SEBA’s Systematic Approach, Split Approach, Jigsaw Perspective, Funnelling Process, Analysis of Data and Non-Data Driven Literature, and SSR Synthesis (Fig. 1), this SSR in SEBA will provide a holistic picture of CST programs [54,55,56,57,58].

To ensure accountability, transparency and reproducibility, an expert team involving medical librarians from the Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine (YLLSoM) at the National University of Singapore and the National Cancer Centre Singapore (NCCS) and local educational experts and clinicians from NCCS, the Palliative Care Institute Liverpool, YLLSoM and Duke-NUS Medical School (henceforth the expert team) will be consulted at each stage of the SEBA methodology [59,60,61,62].

Stage 1: systematic approach

-

A.

Determining the title and background of review

Focusing on CSTs in the postgraduate medical setting, the research and expert teams set out the overall objectives of the SSR in SEBA and determined the population, context and concept to be evaluated.

-

B.

Identifying the research question

The primary question was determined to be: “what is known of prevailing approaches to communication skills training in the postgraduate medical setting?”

-

C.

Inclusion Criteria

A Population, Intervention, Comparison and Outcome (PICOS) format, outlined in Table 1, was adopted to guide the research process [63, 64]. To ensure a sustainable review and to remain focused upon general communication skills used in verbal and non-verbal communications between physicians and patients, we did not include articles focusing on interprofessional communication in this review given its distinct role in training, and in order to accommodate to existing manpower and time constraints [65]. However, articles with a minor focus on interprofessional communication were still included and analysed if their main focus was on physician-patient communication.

-

D.

Identifying relevant studies

Guided by the expert team and prevailing descriptions of CST programs, the research team developed the search strategy for the PubMed, Embase, PsycINFO, ERIC, Scopus, CINAHL, Google Scholar databases. The full PubMed search strategy may be found in Additional file 1: Appendix 1. Independent searches were carried out through the seven databases. All research methodologies (quantitative and qualitative) in articles published or translated into English were included. To accommodate existing manpower and time constraints, the search was confined to articles published between 1st January 2000 and 31st December 2020 [65]. Additional hand searching of seven leading journals in medical education (Academic Medicine, Medical Education, Medical Teacher, Advances Health Sciences Education, BMC Medical Education, Teaching and Learning in Medicine and Perspectives on Medical Education) was conducted to ensure key articles were included. To cover further ground, the references of the included articles obtained from the above methods were screened to further include relevant articles.

-

E.

Selecting studies to be included in the review

Six members of the research team independently reviewed all identified titles and abstracts, created individual lists of titles to be included and discussed these online. Sandelowski and Barroso [66]‘s ‘negotiated consensual validation’ was used to achieve consensus on the final list of titles to be reviewed. Here, ‘negotiated consensual validation’ refers to

“a social process and goal, especially relevant to collaborative, methodological, and integration research, whereby research team members articulate, defend, and persuade others of the “cogency” or “incisiveness” of their points of view or show their willingness to abandon views that are no longer tenable. The essence of negotiated validity is consensus”. (p.229).

Scrutinising the final list of titles to be reviewed, the research team independently downloaded all the full text articles on the final list of titles, studied these, created their own lists of articles to be included and discussed their findings online at research meetings. ‘Negotiated consensual validation’ was used to achieve consensus on the final list of articles to be analysed.

Stage 2: split approach

To enhance the trustworthiness of the review, a Split Approach was employed [67, 68]. This entailed concurrent analysis of the included data using Braun and Clarke [69]‘s approach to thematic analysis and Hsieh and Shannon [70]‘s approach to directed content analysis by two independent groups of at least three reviewers.

-

A.

Thematic Analysis

Three members of the research team employed thematic analysis to independently identify key aspects of CST programs across various learning settings, goals, learner and tutor populations [71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79]. This approach was adopted as it helped to circumnavigate the wide range of research methodologies present amongst the included articles preventing the use of statistical pooling and analysis [80, 81].

A reiterative step-by-step analysis was carried out in which codes were constructed from the explicit surface meaning of the text [82]. In Phase 1, the research team carried out independent reviews and ‘actively’ reading the included articles to find meaning and patterns in the data [82,83,84,85,86]. In Phase 2, codes were collated into a code book to code the rest of the articles. As new codes emerged, these were associated with previous codes and concepts to create subthemes. In Phase 3, the subthemes were organised into themes that best depicted the data. An inductive approach allowed themes to be “defined from the raw data without any predetermined classification” [86]. In Phase 4, the themes were refined to best represent the whole data set. In Phase 5, the research team discussed the results of their independent analysis online and at reviewer meetings. Negotiated consensual validation was used to determine the final list of themes.

-

B.

Directed Content Analysis

Concurrently, three members of the research team employed directed content analysis to independently review all the articles on the final list. This involved “identifying and operationalising a priori coding categories” by classifying text of similar meaning into categories drawn from prevailing theories [87,88,89,90,91]. In keeping with SEBA’s pursuit of an evidence-based approach, the research team selected and extracted codes and categories from Roze des Ordons (2017)‘s article entitled “From Communication Skills to Skillful Communication: A Longitudinal Integrated Curriculum for Critical Care Medicine Fellows” [92]. Use of an evidence-based paradigm article to extract codes from was also in line with SEBA’s goal of ensuring that the review is guided by practical, clinically relevant and applicable data.

In keeping with deductive category application, coding categories were reviewed and revised as required. The research team discussed their findings online to achieve consensus.

Quality assessment of studies

To enhance methodological rigour and to provide reviewers with a chance to evaluate the credibility of the conclusions and the transferability of the findings, two research members carried out individual appraisals of the included quantitative studies using the Medical Education Research Study Quality Instrument (MERSQI) [93] and of the included qualitative studies using the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Studies (COREQ) [94]. The summary of the quality assessments may be found in Additional file 2: Appendix 2 as well.

Stage 3. jigsaw perspective

The themes and categories from the Split Approach are viewed as pieces of a jigsaw puzzle where areas of overlap allow complementary pieces to be combined. These are referred to as themes/categories.

To create themes/categories, the Jigsaw Perspective referenced Phases 4 to 6 of France et al. (2019) [95]‘s adaptation of Noblit and Hare (1998) [96]‘s seven phases of meta-ethnography. As per Phase 4, the themes and the categories identified are grouped according to their focus. These groups are contextualised by reviewing the articles from which the themes and categories were drawn from. This process is facilitated by comparing the findings with tabulated summaries of the included articles that were created in keeping with recommendations drawn from Wong, Greenhalgh [97]‘s “RAMESES publication standards: meta-narrative reviews” and Popay, Roberts [98]‘s “Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews”.

In keeping with France et al’s adaptation, reciprocal translation was used to determine if the themes and categories could be used interchangeably. This allowed the themes and categories to be combined to form themes/categories.

Stage 4: funnelling process

The funnelling process saw the themes/categories juxtaposed with key messages identified in the tabulated summaries (Additional file 1: Appendix 2), and reciprocal translation was used to determine if they truly reflected the data. Once verified, the themes/categories formed funnelled domains and served as the ‘line of argument’ in the discussion synthesis of the SSR in SEBA (Stage 6).

Results

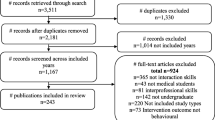

Twenty-five thousand eight hundred ninety-four abstracts were identified, 257 full-text articles were reviewed, and 102 full-text articles were included. ‘Snowballing’ of references from these included articles saw a further 49 full-text articles added and analysed, bringing the total number to 151 (Fig. 2). The Split Approach revealed similar themes and categories allowing the Jigsaw Perspective to forward six themes/categories and the Funnelling Process to forward six funnelled domains: curriculum design, teaching methods, curriculum content, assessment methods, integration into curriculum, and the facilitators and barriers to CST.

For ease of review and given that most of the included articles did not elaborate on many of the domains, the data will be presented in tabulated form.

Curriculum design

A variety of curricula designs were adopted due to differing curricular and program objectives, support and structure; program duration and scheduling in the learner’s training; learner and tutor availabilities, competencies, experiences and settings; assessment methods; education environment; and healthcare and education systems. The principles and models used to structure current CST programs are collated in Table 2.

Teaching methods

Methods to teaching communications may be categorised into didactic and interactive methods. Didactic methods include lectures [3, 13, 116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123], seminars [5, 37], presentations [35, 92, 103, 105, 114, 124,125,126,127,128] and are increasingly hosted on video and online platforms [14, 22, 119, 129, 130]. They are occasionally supplemented by reading material [3, 119, 120].

Interactive methods include role-play with feedback sessions [3, 11, 13, 14, 17, 92, 103,104,105, 108, 118, 120, 121, 124, 127, 129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136], facilitated workshops [5, 103, 107, 118, 137,138,139,140,141,142] and group discussions [6, 13, 37, 92, 111, 121, 127, 130, 137, 143, 144]. Interactive methods are also used to facilitate self-directed learning such as facilitator-independent role-play [139, 142, 145,146,147,148] where participants may choose to rotate amongst themselves through the roles of patient, physician, observer and critic [149]. They also include independently-held group discussions [7, 16, 35, 102, 141, 142, 150, 151] which encourage learners to learn from their peers through observation [130, 131, 142] and feedback [35, 110, 130, 152, 153], as well as engage in introspective reflection on the role and importance of good communication [5, 6, 8, 16, 103, 108, 125, 126, 142, 146, 150, 151, 153,154,155]. Feedback and reflective practice [156,157,158] are increasingly seen as key teaching tools critical to developing adaptive, patient-centred communication, shared decision making and negotiated treatment plans [5, 6, 8, 16, 103, 108, 125, 126, 142, 146, 150, 151, 153,154,155].

Content of curriculum

There are a diverse range of topics within current communications curricula. To remain focused upon communications training between patient and physician, we align our findings with the ‘ACGME Core Competencies: Interpersonal and Communication Skills’ [159] as seen in Table 3.

Amongst this diverse array of topics, there are a few that appear more commonly within particular specialities. These are featured in Table 4.

Assessment methods

There are a variety of assessments methods used to evaluate communication skills. In most of the included articles, details as to when and how these tools are employed were not elaborated upon. Available information is collated in Table 5.

Acknowledging the premise that communication skills develop over time and with experience, practice and reflection, it is increasingly necessary to design assessments at the appropriate stage of the learner's development and setting. These assessment methods may be mapped according to the progressive levels of Kirkpatrick’s Four Levels of Learning Evaluation (Table 6) [143].

Integration of training

Most programs were part of a formal residency/ fellowship curriculum which provided ‘protected time’ for teaching [141]. However, these programs varied in duration with some offering CST as a single component of scheduled teachings and grand rounds, whilst others via a stand-alone communications retreat, workshop or course [11, 12, 119, 125, 126, 135, 137, 146, 147, 185, 208]. These ad-hoc sessions were often more flexible [114, 149, 173] to accommodate to the busy schedules of the physicians [143]. They tended to be shorter in duration, ranging from 1 to 3 hours per session and focused on the specific needs of the learner population [16, 111, 149, 167].

Others spanned several sessions [3, 6, 13, 14, 35, 37, 99, 116, 123, 124, 131, 139, 140, 199, 202, 212, 218]. These longitudinal sessions were often structured in a step-wise manner, with the intent of first delivering key knowledge and developing requisite skills before more complicated topics are introduced [22, 36, 92, 117, 127], highlighting vertical integration within the spiralled curriculum. These multiple sessions often take place during specific rotations at regular intervals [13, 17, 35, 103, 107, 121, 130, 142, 153, 174, 175] over several months [7, 33, 100, 104, 118, 128, 133, 134, 150, 151, 160, 165]. For example, Ungar et al. [130] implemented a 14-session ‘breaking bad news’ training program for second-year family medicine residents where core skills in acknowledging patient needs were first taught, followed by techniques on breaking bad news and confronting distressing questions. Newcomb et al. [127] used a similar spiralled curriculum that extended over a two-year period to teach communication skills to surgical residents with more advanced topics such as crisis management coming in at a later stage.

Resources, facilitators and barriers to CST

-

a.

Resources

Resources required to establish and sustain CST programs are summarised in Table 7.

-

b.

Facilitators

Facilitators are factors that aid effective delivery and reception of CST. These include faculty support [37, 92, 108, 127], opportunities to attend courses [151], a platform for feedback [92], faculty training [105, 116, 124, 129, 132, 133, 153, 185, 199, 200, 208] and simulation sessions [13, 119, 135, 186].

-

c.

Barriers

Barriers impede CST programs. These barriers include curriculum factors, physician factors and patient factors. Curriculum factors include the lack of protected time [35, 37, 117, 119, 125, 127, 146, 147, 149, 153, 170, 173,174,175], logistical and manpower constraints [14, 32, 100, 139, 142, 145, 146, 150], inadequate resources [150], inadequate faculty support [37, 117] and a lack of buy in from participants and colleagues [92].

Physician factors include overcoming complacency with regards to CST [16, 99, 175, 202], overemphasis on technical aspects of clinical practice over soft skills [36, 102, 124, 150, 173] and difficulty measuring communication-related performance indices [8, 171].

Patient factors encompass both simulated patients and real patients. Simulated patients have to be recruited, trained and remunerated [14, 120, 131, 145]. Employ of former patients acting as simulated patients creates concerns over their biases and wellbeing [12, 36]. Limitations of having staff or peers take on the role of simulated patient lie in their variable acting skills and their ability to convey the gravity of the situation and the integrity of the encounter [12]. On the other hand, real patients may give little to no criticism to their physicians, hence limiting awareness of areas of improvement [118, 202]. Elderly patients are especially unwilling to disclose their emotional distress thus making it difficult for physicians to pick up social clues [118]. Patients may also mistakenly perceive politeness as having good communication skills [202].

Stage 5: analysis of evidence and non-evidence-based literature

With quality appraisals highlighting that data taken from grey literature, opinion, perspectives, editorial, letters and other non-primary data-based articles (henceforth non-evidence-based data) were shown to be consistently poor, the expert team determined that the impact of non-evidence-based data upon the discussions and conclusions drawn in the SSR in SEBA should be evaluated.

To do so, the research team carried out separate and independent reviews and thematic analyses of evidence-based data from bibliographic databases and compared them to the themes drawn from non-evidence-based data. The themes from both groups were found to be similar, thus allowing the expert and research teams to conclude that the non-evidence-based data included in this review did not bias the analysis untowardly.

Discussion

Stage 6: synthesis of SSR in SEBA

In answering its primary research question, this SSR in SEBA reveals growing employ of designated CST programs within formal curricula. Taking the form of spiralled curricula to support structured and longitudinal programs, many CST programs use a combination of didactic and interactive approaches in tandem with context-dependent tools aimed at assessing the learner’s expected abilities so as to facilitate learner-specific feedback and support. This maturing approach to CST in postgraduate medical education is scaffolded upon horizontal and vertical integration of communications training that sees CST training sessions carried out at a point where particular topics are especially relevant to the learner, highlighting greater education theory grounded approaches in their design [127, 130]. This underlines the rationale for different contents being inculcated in different settings.

Efforts at curricula design of CST programs, too, have taken a more holistic perspective with programs being framed by clearly delineated design models, frameworks and/or guiding principles. This may involve use of situation-specific guidelines such as SPIKES [101, 112, 113]. Yet, this approach also pays due consideration to the setting and relevance of the content in order to motivate the learner to actively participate in a CST session that activates their prevailing knowledge and skills. Use of Knowles’s Adult Learning Theory and its latter reiterations such as Taylor and Hamdy [220]‘s Multi-theories Model that include Kolb’s Cycle [221, 222] scaffolded around Miller’s Pyramid have also guided the integration of reflective practice and timely, personalised and appropriate support in formal curricula. Use of formal curricula also helps ensure that structured interactions set the stage for longitudinal development of skills and knowledge, ‘protected time’ for communication teaching, and better blending of didactic sessions with interactive sessions at ward rounds and grand rounds and/or online discussions.

Based upon the findings and current design principles identified in this SSR in SEBA, we forward a stepwise approach to designing CST programs. This is outlined in Table 8.

Based on the principles set out in Table 8, we believe that this structured framework to the teaching and assessment of CSTs may be used in a variety of contextual and sociocultural settings and fine-tuned to the learner’s knowledge, skills, attitudes and, increasingly, behaviour over time.

The culmination of these finding also brings to the fore several considerations, not least the notion that CST programs should be blended with CST in medical schools so as to deepen and widen the spiralled curriculum. Such an approach would necessitate the use of portfolios to inform learners and tutors of communication gaps, and facilitate reflections, remediation and progress towards the achievement of overarching Entrustable Professional Activities (EPA)s [223, 224]. Changing thinking, attitudes, conduct and practice also alludes to the role of CST in professional identity formation which also warrants further study.

Limitations

Whilst we have conducted a three-tiered searching strategy, through independent searching of selected databases, repeated sieving of reference lists of the included articles (snowballing) and searching of prominent medical education journals, the usage of specific terms and inclusion of only papers in the English languages may have led to important papers being missed. Similarly, whilst use of the Split Approach and tabulated summaries in SEBA allowed for triangulation and ensured that a holistic perspective was constructed, inherent biases amongst the reviewers would still impact the analysis of the data and construction of themes.

However, we believe that through the employment of SEBA, this review has the required rigour and transparency to render this a reproducible and comprehensive article. We hope that the findings of this systematic scoping review will be of interest to educators and program designers in the postgraduate medical setting and will help to guide the design of successful CST programs to fortify physicians in this essential domain.

Conclusion

As we look forward to engaging in this exciting and rapidly evolving aspect of medical education and practice, we hope to evaluate our proposed framework in practice in our coming research and focus attention upon the use of portfolios in CST programs. This is particularly in considering the possibility that CST may have a hand in shaping professional identity formation. Further understanding of theories and approaches underpinning CST use within medical training is in need of further study as is the role of online multimedia platforms and the medical humanities in teaching adaptive, empathetic and personalised communication skills.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Abbreviations

- ACGME:

-

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education

- COREQ:

-

Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Studies

- CST:

-

Communication Skills Training

- GME:

-

Graduate Medical Education

- MERSQI:

-

Medical Education Research Study Quality Instrument

- NCCS:

-

National Cancer Centre Singapore

- PICOS:

-

Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, Study design

- SEBA:

-

Systematic Evidence-Based Approach

- SSR:

-

Systematic Scoping Review

- YLLSoM:

-

Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine

References

Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality of Health Care in A. In: Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, editors. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington: National Academies Press (US) Copyright 2000 by the National Academy of Sciences; 2000.

Hausberg MC, Hergert A, Kröger C, Bullinger M, Rose M, Andreas S. Enhancing medical students’ communication skills: development and evaluation of an undergraduate training program. BMC medical education. 2012;12:16.

Moore PM, Rivera Mercado S, Grez Artigues M, Lawrie TA. Communication skills training for healthcare professionals working with people who have cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2013(3):Cd003751.

Bylund CL, Brown RF, Lubrano di Ciccone B, Diamond C, Eddington J, Kissane DW. Assessing facilitator competence in a comprehensive communication skills training program. Med Educ. 2009;43(4):342–9.

Marchand L, Kushner K. Death pronouncements: using the teachable moment in end-of-life care residency training. J Palliat Med. 2004;7(1):80–4.

Patki A, Puscas L. A video-based module for teaching communication skills to otolaryngology residents. J Surg Educ. 2015;72(6):1090–4.

Peterson EB, Boland KA, Bryant KA, McKinley TF, Porter MB, Potter KE, et al. Development of a comprehensive communication skills curriculum for pediatrics residents. J Grad Med Educ. 2016;8(5):739–46.

Raper SE, Gupta M, Okusanya O, Morris JB. Improving communication skills: a course for Academic Medical Center surgery residents and faculty. J Surg Educ. 2015;72(6):e202–11.

Noordman J, Verhaak P, van Dulmen S. Web-enabled video-feedback: a method to reflect on the communication skills of experienced physicians. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;82(3):335–40.

Orgel E, McCarter R, Jacobs S. A failing medical educational model: a self-assessment by physicians at all levels of training of ability and comfort to deliver bad news. J Palliat Med. 2010;13(6):677–83.

Szmuilowicz E, El-Jawahri A, Chiappetta L, Kamdar M, Block S. Improving residents’ end-of-life communication skills with a short retreat: a randomized controlled trial. J Palliat Med. 2010;13(4):439–52.

Trickey AW, Newcomb AB, Porrey M, Wright J, Bayless J, Piscitani F, et al. Assessment of surgery Residents’ interpersonal communication skills: validation evidence for the communication assessment tool in a simulation environment. J Surg Educ. 2016;73(6):e19–27.

Hope AA, Hsieh SJ, Howes JM, Keene AB, Fausto JA, Pinto PA, et al. Let’s talk critical. development and evaluation of a communication skills training program for critical care fellows. Ann Am Thoracic Soc. 2015;12(4):505–11.

Levinson W, Lesser CS, Epstein RM. Developing physician communication skills for patient-centered care. Health Affairs (Project Hope). 2010;29(7):1310–8.

Ha JF, Longnecker N. Doctor-patient communication: a review. Ochsner J. 2010;10(1):38–43.

Clayton JM, Adler JL, O’Callaghan A, Martin P, Hynson J, Butow PN, et al. Intensive communication skills teaching for specialist training in palliative medicine: development and evaluation of an experiential workshop. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(5):585–91.

Roter DL, Larson S, Shinitzky H, Chernoff R, Serwint JR, Adamo G, et al. Use of an innovative video feedback technique to enhance communication skills training. Med Educ. 2004;38(2):145–57.

van Dalen J, Kerkhofs E, van Knippenberg-Van Den Berg BW, van Den Hout HA, Scherpbier AJ, van der Vleuten CP. Longitudinal and concentrated communication skills programs: two dutch medical schools compared. Adv Health Sci Educ. 2002;7(1):29–40.

Ament Giuliani Franco C, Franco RS, Cecilio-Fernandes D, Severo M, Ferreira MA, de Carvalho-Filho MA. Added value of assessing medical students’ reflective writings in communication skills training: a longitudinal study in four academic centres. BMJ Open. 2020;10(11):e038898.

Hoffmann TC, Bennett S, Tomsett C, Del Mar C. Brief training of student clinicians in shared decision making: a single-blind randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(6):844–9.

Givron H, Desseilles M. Longitudinal study: impact of communication skills training and a traineeship on medical students’ attitudes toward communication skills. Patient Educ Couns. 2021;104(4):785–91.

Kramer AW, Düsman H, Tan LH, Jansen JJ, Grol RP, van der Vleuten CP. Acquisition of communication skills in postgraduate training for general practice. Med Educ. 2004;38(2):158–67.

Kow CS, Teo YH, Teo YN, Chua KZY, Quah ELY, Kamal NHBA, et al. A systematic scoping review of ethical issues in mentoring in medical schools. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):1–10.

Bok C, Ng CH, Koh JWH, Ong ZH, Ghazali HZB, Tan LHE, et al. Interprofessional communication (IPC) for medical students: a scoping review. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):372.

Ngiam L, Xin L, et al. “Impact of Caring for Terminally Ill Children on Physicians: A Systematic Scoping Review.” The American journal of hospice & palliative care. 2021;38(4):396–418. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909120950301.

Krishna LKR, Tan LHE, Ong YT, Tay KT, Hee JM, Chiam M, et al. Enhancing mentoring in palliative care: an evidence based mentoring framework. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2020;7:2382120520957649.

Kamal NHA, Tan LHE, Wong RSM, Ong RRS, Seow REW, Loh EKY, et al. Enhancing education in palliative medicine: the role of systematic scoping reviews. Palliat Med Care. 2020;7(1):1–11.

Ong RRS, Seow REW, Wong RSM, Loh EKY, Kamal NHA, Mah ZH, et al. A systematic scoping review of narrative reviews in palliative medicine education. Palliat Med Care. 2020;7(1):1–22.

Mah ZH, Wong RSM, Seow REW, Loh EKY, Kamal NHA, Ong RRS, et al. A systematic scoping review of systematic reviews in palliative medicine education. Palliat Med Care. 2020;7(1):1–12.

Armstrong R, Hall BJ, Doyle J, Waters E. Cochrane update. ‘Scoping the scope’ of a cochrane review. J. Public Health (Oxf). 2011;33(1):147–50.

Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):143.

Raper SE, Resnick AS, Morris JB. Simulated disclosure of a medical error by residents: development of a course in specific communication skills. J Surg Educ. 2014;71(6):e116–e26.

Riess H, Kelley JM, Bailey R, Konowitz PM, Gray ST. Improving empathy and relational skills in otolaryngology residents: a pilot study. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;144(1):120–2.

Silva DH. A competency-based communication skills workshop series for pediatric residents. Bol Asoc Med P R. 2008;100(2):8–12.

Smith L, O’Sullivan P, Lo B, Chen H. An educational intervention to improve resident comfort with communication at the end of life. J Palliat Med. 2013;16(1):54–9.

Trickey AW, Newcomb AB, Porrey M, Piscitani F, Wright J, Graling P, et al. Two-year experience implementing a curriculum to improve Residents’ patient-centered communication skills. J Surg Educ. 2017;74(6):e124–e32.

Weissmann PF. Teaching advanced interviewing skills to residents: a curriculum for institutions with limited resources. Med Educ Online. 2006;11(1):4584.

Myerholtz L. Assessing family medicine Residents’ communication skills from the Patient’s perspective: evaluating the communication assessment tool. J Graduate Med Educ. 2014;6(3):495–500.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73.

Horsley T. Tips for improving the writing and reporting quality of systematic, scoping, and narrative reviews. J Contin Educ Heal Prof. 2019;39(1):54–7.

Yoon NYS, Ong YT, Yap HW, Tay KT, Lim EG, Cheong CWS, et al. Evaluating assessment tools of the quality of clinical ethics consultations: a systematic scoping review from 1992 to 2019. BMC Med Ethics. 2020;21(1):51.

Tay KT, Tan XH, Tan LHE, Vythilingam D, Chin AMC, Loh V, et al. A systematic scoping review and thematic analysis of interprofessional mentoring in medicine from 2000 to. J Interprof Care. 2019;2020:1–13.

Tay KT, Ng S, Hee JM, Chia EWY, Vythilingam D, Ong YT, et al. Assessing professionalism in medicine - a scoping review of assessment tools from 1990 to 2018. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2020;7:2382120520955159.

Shiva S-Y, et al. “A Scoping Review of Professional Identity Formation in Undergraduate Medical Education.” J Gen Intern Med. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-07024-9.

Ngiam LXL, Ong YT, Ng JX, Kuek JTY, Chia JL, Chan NPX, et al. Impact of caring for terminally ill children on physicians: a systematic scoping review. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2021;38(4):396–418.

Kuek JTY, Ngiam LXL, Kamal NHA, Chia JL, Chan NPX, Abdurrahman A, et al. The impact of caring for dying patients in intensive care units on a physician’s personhood: a systematic scoping review. Philos Ethics Humanit Med. 2020;15(1):12.

Hong DZ, et al. “A Systematic Scoping Review on Portfolios of Medical Educators.” J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1177/23821205211000356.

Hong DZ, Goh JL, Ong ZY, et al. Postgraduate ethics training programs: a systematic scoping review. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21:338. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-02644-5.

Ho S, Tan YY, Neo SHS, Zhuang Q, Chiam M, Zhou JX, et al. COVID-19 - a review of the impact it has made on supportive and palliative care services within a tertiary hospital and Cancer Centre in Singapore. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2020;49(7):489–95.

Ho CY, Kow CS, Chia CHJ, Low JY, Lai YHM, Lauw SK, et al. The impact of death and dying on the personhood of medical students: a systematic scoping review. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):516.

Hee J, Toh YL, Yap HW, Toh YP, Kanesvaran R, Mason S, et al. The development and Design of a Framework to match mentees and mentors through a systematic review andThematic analysis of mentoring programs between 2000 and 2015. Mentoring Tutoring. 2020;28(3):340–64.

Chua WJ, Cheong CWS, Lee FQH, Koh EYH, Toh YP, Mason S, et al. Structuring mentoring in medicine and surgery. A systematic scoping review of mentoring programs between 2000 and 2019. J Contin Educ Heal Prof. 2020;40(3):158–68.

Chia EWY, Tay KT, Xiao S, Teo YH, Ong YT, Chiam M, et al. The pivotal role of host organizations in enhancing mentoring in internal medicine: a scoping review. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2020;7:2382120520956647.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Inform Libr J. 2009;26(2):91–108.

Lorenzetti DL, Powelson SE. A scoping review of mentoring programs for academic librarians. J Acad Librariansh. 2015;41(2):186–96.

Mays N, Roberts E, Popay J. Synthesising research evidence. Studying the organization and delivery of health services: research methods. Edited by: Fulop N, Allen P, Clarke A, Black N. London: Routledge; 2001.

Thomas A, Menon A, Boruff J, Rodriguez AM, Ahmed S. Applications of social constructivist learning theories in knowledge translation for healthcare professionals: a scoping review. Implement Sci. 2014;9(1):54.

Pring R. The ‘false dualism’of educational research. J Philos Educ. 2000;34(2):247–60.

Crotty M. The foundations of social research: meaning and perspective in the research process: SAGE; 1998.

Ford K. Taking a narrative turn: possibilities, Challenges and Potential Outcomes. OnCUE Journal; 2012.

Schick-Makaroff K, MacDonald M, Plummer M, Burgess J, Neander W. What synthesis methodology should I use? A review and analysis of approaches to research synthesis. AIMS Public Health. 2016;3:172–215.

Peters M, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Soares C, Khalil H, Parker D. The Joanna Briggs institute reviewers’ manual 2015: methodology for JBI scoping reviews2015 April 29, 2019. Available from: http://joannabriggs.org/assets/docs/sumari/Reviewers-Manual_Methodology-for-JBI-Scoping-Reviews_2015_v1.pdf.

Peters MD, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, Parker D, Soares CB. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):141–6.

Pham MT, Rajić A, Greig JD, Sargeant JM, Papadopoulos A, McEwen SA. A scoping review of scoping reviews: advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Res Synth Methods. 2014;5(4):371–85.

Sandelowski M, Barroso J. Handbook for synthesizing qualitative research. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 2006. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-02892-5.

Wen Jie Chua CWSC, Lee FQH, Koh EYH, Toh YP, Mason S, Krishna LKR. Structuring Mentoring in Medicine and Surgery. A Systematic Scoping Review of Mentoring Programs Between 2000 and 2019. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2020;40(3):158–68.

Ng YX, Koh ZYK, Yap HW, Tay KT, Tan XH, Ong YT, et al. Assessing mentoring: a scoping review of mentoring assessment tools in internal medicine between 1990 and 2019. PLoS One. 2020;15(5):e0232511.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–88.

Sng JH, Pei Y, Toh YP, Peh TY, Neo SH, Krishna LKR. Mentoring relationships between senior physicians and junior doctors and/or medical students: a thematic review. Med Teach. 2017;39(8):866–75.

Wahab MT, Ikbal MFBM, Wu J, Loo WTW, Kanesvaran R, Krishna LKR. Creating Effective Interprofessional Mentoring Relationships in Palliative Care- Lessons from Medicine, Nursing, Surgery and Social Work. J Palliat Care Med. 2016;06(06):1.

Toh YP, Lam B, Soo J, Chua KLL, Krishna L. Developing palliative care physicians through mentoring relationships. Palliat Med Care. 2017;4(1):1–6.

Wu J, Wahab MT, Ikbal MFBM, Loo TWW, Kanesvaran R, Krishna LKR. Toward an Interprofessional mentoring program in palliative care - a review of undergraduate and postgraduate mentoring in medicine, nursing, surgery and social work. J Palliat Care Med. 2016;06(06):1–11.

Soemantri D, Herrera C, Riquelme A. Measuring the educational environment in health professions studies: a systematic review. Med Teach. 2010;32(12):947–52.

Schönrock-Adema J, Heijne-Penninga M, van Hell EA, Cohen-Schotanus J. Necessary steps in factor analysis: enhancing validation studies of educational instruments. The PHEEM applied to clerks as an example. Med Teach. 2009;31(6):e226–e32.

Riquelme A, Herrera C, Aranis C, Oporto J, Padilla O. Psychometric analyses and internal consistency of the PHEEM questionnaire to measure the clinical learning environment in the clerkship of a medical School in Chile. Med Teach. 2009;31(6):e221–e5.

Herrera C, Pacheco J, Rosso F, Cisterna C, Daniela A, Becker S, et al. Evaluation of the undergraduate educational environment in six medical schools in Chile. Revista medica de Chile. 2010;138(6):677–84.

Strand P, Sjöborg K, Stalmeijer R, Wichmann-Hansen G, Jakobsson U, Edgren G. Development and psychometric evaluation of the undergraduate clinical education environment measure (UCEEM). Med Teach. 2013;35(12):1014–26.

Gordon M, Gibbs T. STORIES statement: publication standards for healthcare education evidence synthesis. BMC Med. 2014;12(1):143.

Haig A, Dozier M. BEME guide no 3: systematic searching for evidence in medical education--part 1: sources of information. Med Teach. 2003;25(4):352–63.

Stenfors-Hayes T, Kalén S, Hult H, Dahlgren LO, Hindbeck H, Ponzer S. Being a mentor for undergraduate medical students enhances personal and professional development. Med Teach. 2010;32(2):148–53.

Boyatzis RE. Transforming qualitative information: thematic analysis and code development SAGE publishing; 1998.

Sawatsky AP, Parekh N, Muula AS, Mbata I, Bui TJM. Cultural implications of mentoring in sub-Saharan Africa: a qualitative study. Med Educ. 2016;50(6):657–69.

Voloch K-A, Judd N, Sakamoto KJH. An innovative mentoring program for Imi Ho’ola Post-Baccalaureate students at the University of Hawai’i John A. Burns Sch Med. 2007;66(4):102.

Cassol H, Pétré B, Degrange S, Martial C, Charland-Verville V, Lallier F, et al. Qualitative thematic analysis of the phenomenology of near-death experiences. PLoS One. 2018;13(2):e0193001.

Neal JW, Neal ZP, Lawlor JA, Mills KJ, McAlindon KJA, Health PM, et al. What makes research useful for public school educators? Adm Policy Ment Health. 2018;45(3):432–46.

Wagner-Menghin M, de Bruin A, van Merriënboer JJ. Monitoring communication with patients: analyzing judgments of satisfaction (JOS). Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2016;21(3):523–40.

Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62(1):107–15.

Mayring P. Qualitative content analysis. Companion Qual Res. 2004;1:159–76.

Humble ÁM. Technique triangulation for validation in directed content analysis. Int J Qual Methods. 2009;8(3):34–51.

Roze des Ordons AL, Doig CJ, Couillard P, Lord J. From communication skills to skillful communication: a longitudinal integrated curriculum for critical care medicine fellows. Acad Med. 2017;92(4):501–5.

Reed DA, Beckman TJ, Wright SM, Levine RB, Kern DE, Cook DA. Predictive validity evidence for medical education research study quality instrument scores: quality of submissions to JGIM’s medical education special issue. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(7):903–7.

Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–57.

France EF, Wells M, Lang H, Williams B. Why, when and how to update a meta-ethnography qualitative synthesis. Syst Rev. 2016;5:44.

Noblit GW, Hare D. Meta-ethnography: synthesizing qualitative studies. California: SAGE Publications; 1988. p. 88.

Wong G, Greenhalgh T, Westhorp G, Buckingham J, Pawson R. RAMESES publication standards: Meta-narrative reviews. BMC Med. 2013;11:20.

Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, Petticrew M, Arai L, Rodgers M, et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews: A product from the ESRC Methods Program. 2006.

Salib S, Glowacki EM, Chilek LA, Mackert M. Developing a communication curriculum and workshop for an internal medicine residency program. South Med J. 2015;108(6):320–4.

Wood J, Collins J, Burnside ES, Albanese MA, Propeck PA, Kelcz F, et al. Patient, faculty, and self-assessment of radiology resident performance: a 360-degree method of measuring professionalism and interpersonal/communication skills. Acad Radiol. 2004;11(8):931–9.

Back AL, Arnold RM, Baile WF, Fryer-Edwards KA, Alexander SC, Barley GE, et al. Efficacy of communication skills training for giving bad news and discussing transitions to palliative care. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(5):453–60.

Bayona J, Goodrich TJ. The integrative care conference: an innovative model for teaching at the heart of communication in medicine. Teach Learn Med. 2008;20(2):174–9.

McCallister JW, Gustin JL, Wells-Di Gregorio S, Way DP, Mastronarde JG. Communication skills training curriculum for pulmonary and critical care fellows. Ann Am Thoracic Society. 2015;12(4):520–5.

Nikendei C, Bosse HM, Hoffmann K, Moltner A, Hancke R, Conrad C, et al. Outcome of parent-physician communication skills training for pediatric residents. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;82(1):94–9.

Brown R, Bylund CL, Eddington J, Gueguen JA, Kissane DW. Discussing prognosis in an oncology setting: initial evaluation of a communication skills training module. Psycho-Oncology. 2010;19(4):408–14.

Brown RF, Bylund CL. Communication skills training: describing a new conceptual model. Acad Med. 2008;83(1):37–44.

Schoenborn NL, Boyd C, Cayea D, Nakamura K, Xue QL, Ray A, et al. Incorporating prognosis in the care of older adults with multimorbidity: description and evaluation of a novel curriculum. BMC Med Educ. 2015;15:215.

Fiorentino M, et al. “Teaching Residents Communication Skills around Death and Dying in the Trauma Bay.” J Palliat Med. 2021;24(1):77–82. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2020.0076.

Gelfman LP, Lindenberger E, Fernandez H, Goldberg GR, Lim BB, Litrivis E, et al. The effectiveness of the Geritalk communication skills course: a real-time assessment of skill acquisition and deliberate practice. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2014;48(4):738–44.e1–6.

O'Shaughnessy SM. Peer teaching as a means of enhancing communication skills in anaesthesia training: trainee perspectives. Ir J Med Sci. 2018;187(1):207–13.

Nørgaard B, Ammentorp J, Ohm Kyvik K, Kofoed PE. Communication skills training increases self-efficacy of health care professionals. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2012;32(2):90–7.

Schellenberg KL, Schofield SJ, Fang S, Johnston WS. Breaking bad news in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: the need for medical education. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2014;15(1–2):47–54.

Ghoneim N, Dariya V, Guffey D, Minard CG, Frugé E, Harris LL, et al. Teaching NICU fellows How to relay difficult news using a simulation-based curriculum: does comfort Lead to competence? Teach Learn Med. 2019;31(2):207–21.

Bylund CL, Brown R, Gueguen JA, Diamond C, Bianculli J, Kissane DW. The implementation and assessment of a comprehensive communication skills training curriculum for oncologists. Psycho-Oncology. 2010;19(6):583–93.

Yakhforoshha A, Emami SAH, Shahi F, Shahsavari S, Cheraghi M, Mojtahedzadeh R, et al. Effectiveness of integrating simulation with art-based teaching strategies on oncology Fellows’ performance regarding breaking bad news. J Cancer Educ. 2019;34(3):463–71.

Fujimori M, Oba A, Koike M, Okamura M, Akizuki N, Kamiya M, et al. Communication skills training for Japanese oncologists on How to break bad news. J Cancer Educ. 2003;18(4):194–201.

Hoffman M, Ferri J, Sison C, Roter D, Schapira L, Baile W. Teaching communication skills: an AACE survey of oncology training programs. J Cancer Educ. 2004;19(4):220–4.

Merckaert I, Libert Y, Delvaux N, Marchal S, Boniver J, Etienne AM, et al. Factors that influence physicians’ detection of distress in patients with cancer: can a communication skills training program improve physicians’ detection? Cancer. 2005;104(2):411–21.

Haglund MM, Rudd M, Nagler A, Prose NS. Difficult conversations: a national course for neurosurgery residents in physician-patient communication. J Surg Educ. 2015;72(3):394–401.

Merckaert I, Libert Y, Razavi D. Communication skills training in cancer care: where are we and where are we going? Curr Opin Oncol. 2005;17(4):319–30.

Park I, Gupta A, Mandani K, Haubner L, Peckler B. Breaking bad news education for emergency medicine residents: a novel training module using simulation with the SPIKES protocol. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2010;3(4):385–8.

Clayton JM, Butow PN, Waters A, Laidsaar-Powell RC, O’Brien A, Boyle F, et al. Evaluation of a novel individualised communication-skills training intervention to improve doctors’ confidence and skills in end-of-life communication. Palliat Med. 2013;27(3):236–43.

Fellowes D, et al. “Communication skills training for health care professionals working with cancer patients, their families and/or carers.” Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;2:CD003751. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003751.pub2.

Kelley AS, Back AL, Arnold RM, Goldberg GR, Lim BB, Litrivis E, et al. Geritalk: communication skills training for geriatric and palliative medicine fellows. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(2):332–7.

Miller DC, Sullivan AM, Soffler M, Armstrong B, Anandaiah A, Rock L, et al. Teaching residents How to talk about death and dying: a mixed-methods analysis of barriers and randomized educational intervention. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2018;35(9):1221–6.

Wong RY, Saber SS, Ma I, Roberts JM. Using television shows to teach communication skills in internal medicine residency. BMC Med Educ. 2009;9:9.

Newcomb AB, Trickey AW, Porrey M, Wright J, Piscitani F, Graling P, et al. Talk the talk: implementing a communication curriculum for surgical residents. J Surg Educ. 2017;74(2):319–28.

Cannone D, Atlas M, Fornari A, Barilla-LaBarca ML, Hoffman M. Delivering challenging news: an illness-trajectory communication curriculum for multispecialty oncology residents and fellows. MedEdPORTAL. 2019;15:10819.

Kissane DW, Bylund CL, Banerjee SC, Bialer PA, Levin TT, Maloney EK, et al. Communication skills training for oncology professionals. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(11):1242–7.

Ungar L, Alperin M, Amiel GE, Beharier Z, Reis S. Breaking bad news: structured training for family medicine residents. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;48(1):63–8.

Dacre J, Richardson J, Noble L, Stephens K, Parker N. Communication skills training in postgraduate medicine: the development of a new course. Postgrad Med J. 2004;80(950):711–5.

Hardoff D, Schonmann S. Training physicians in communication skills with adolescents using teenage actors as simulated patients. Med Educ. 2001;35(3):206–10.

Liénard A, Merckaert I, Libert Y, Bragard I, Delvaux N, Etienne AM, et al. Is it possible to improve residents breaking bad news skills? A randomised study assessing the efficacy of a communication skills training program. Br J Cancer. 2010;103(2):171–7.

Mjaaland TA, Finset A. Communication skills training for general practitioners to promote patient coping: the GRIP approach. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;76(1):84–90.

Smith PE, Fuller GN, Kinnersley P, Brigley S, Elwyn G. Using simulated consultations to develop communications skills for neurology trainees. Eur J Neurol. 2002;9(1):83–7.

Alexander SC, Keitz SA, Sloane R, Tulsky JA. A controlled trial of a short course to improve residents’ communication with patients at the end of life. Acad Med. 2006;81(11):1008–12.

Chandawarkar RY, Ruscher KA, Krajewski A, Garg M, Pfeiffer C, Singh R, et al. Pretraining and posttraining assessment of residents’ performance in the fourth accreditation council for graduate medical education competency: patient communication skills. Arch Surg (Chicago, Ill : 1960). 2011;146(8):916–21.

Cinar O, Ak M, Sutcigil L, Congologlu ED, Canbaz H, Kilic E, et al. Communication skills training for emergency medicine residents. Eur J Emerg Med. 2012;19(1):9–13.

Lenzi R, Baile WF, Costantini A, Grassi L, Parker PA. Communication training in oncology: results of intensive communication workshops for Italian oncologists. Eur J Cancer Care. 2011;20(2):196–203.

Manze MG, Orner MB, Glickman M, Pbert L, Berlowitz D, Kressin NR. Brief provider communication skills training fails to impact patient hypertension outcomes. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98(2):191–8.

Tobler K, Grant E, Marczinski C. Evaluation of the impact of a simulation-enhanced breaking bad news workshop in pediatrics. Simulation in healthcare : journal of the Society for Simulation in Healthcare. 2014;9(4):213–9.

Williams DM, Fisicaro T, Veloski JJ, Berg D. Development and evaluation of a program to strengthen first year residents’ proficiency in leading end-of-life discussions. The American journal of hospice & palliative care. 2011;28(5):328–34.

Ghofranipour F, Ghaffarifar S, Ahmadi F, Hosseinzadeh H, Akbarzadeh A. Peter Walla (Reviewing editor). Improving interns’ patient–physician communication skills: Application of self-efficacy theory, a pilot study, Cogent Psychology. 2018;5:1. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2018.1524083.

Back AL, Arnold RM, Tulsky JA, Baile WF, Fryer-Edwards KA. Teaching communication skills to medical oncology fellows. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2003;21(12):2433–6.

Lim EC, Oh VM, Seet RC. Overcoming preconceptions and perceived barriers to medical communication using a ‘dual role-play’ training course. Intern Med J. 2008;38(9):708–13.

Razack S, Meterissian S, Morin L, Snell L, Steinert Y, Tabatabai D, et al. Coming of age as communicators: differences in the implementation of common communications skills training in four residency programs. Med Educ. 2007;41(5):441–9.

Young OM, Parviainen K. Training obstetrics and gynecology residents to be effective communicators in the era of the 80-hour workweek: a pilot study. BMC research notes. 2014;7:455.

Arnold RM, Back AL, Barnato AE, Prendergast TJ, Emlet LL, Karpov I, et al. The critical care communication project: improving fellows’ communication skills. J Crit Care. 2015;30(2):250–4.

Ju M, Berman AT, Vapiwala N. Standardized patient training programs: an efficient solution to the call for quality improvement in oncologist communication skills. Journal of cancer education : the official journal of the American Association for Cancer Education. 2015;30(3):466–70.

Cameron N, McMillan R. Enhancing communication skills by peer review of consultation videos. Education for Primary Care. 2006;17(1):40–8.

Watling CJ, Brown JB. Education research: communication skills for neurology residents: structured teaching and reflective practice. Neurology. 2007;69(22):E20–6.

Christie D, Glew S. A clinical review of communication training for haematologists and haemato-oncologists: a case of art versus science. Br J Haematol. 2017;178(1):11–9.

Sullivan AM, Rock LK, Gadmer NM, Norwich DE, Schwartzstein RM. The impact of resident training on communication with families in the intensive care unit. Resident and family outcomes. Annals of the American Thoracic Society. 2016;13(4):512–21.

Lloyd G, Skarratts D, Robinson N, Reid C. Communication skills training for emergency department senior house officers--a qualitative study. J Accid Emerg Med. 2000;17(4):246–50.

Wouda JC, van de Wiel HB. The effects of self-assessment and supervisor feedback on residents’ patient-education competency using videoed outpatient consultations. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;97(1):59–66.

Ammentorp J, Sabroe S, Kofoed PE, Mainz J. The effect of training in communication skills on medical doctors’ and nurses’ self-efficacy. A randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;66(3):270–7.

Ranjan P, Kumari A, Chakrawarty A. How can doctors improve their communication skills? J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9(3):JE01–4.

Wright EB, Holcombe C, Salmon P. Doctors’ communication of trust, care, and respect in breast cancer: qualitative study. BMJ. 2004;328(7444):864.

Team NK. Exploring The ACGME Core Competencies (Part 6 Of 7) - NEJM Knowledge+". NEJM Knowledge+, 2021. https://knowledgeplus.nejm.org/blog/acgme-core-competencies-interpersonal-and-communication-skills/.

Mitchell JD, Ku C, Wong V, Fisher LJ, Muret-Wagstaff SL, Ott Q, et al. The impact of a resident communication skills curriculum on Patients’ experiences of care. A & A case reports. 2016;6(3):65–75.

Ishikawa H, Son D, Eto M, Kitamura K, Kiuchi T. Changes in patient-centered attitude and confidence in communicating with patients: a longitudinal study of resident physicians. BMC medical education. 2018;18(1):20.

Deveugele M. Communication training: skills and beyond. Patient Educ Couns. 2015;98(10):1287–91.

Wild D, Nawaz H, Ullah S, Via C, Vance W, Petraro P. Teaching residents to put patients first: creation and evaluation of a comprehensive curriculum in patient-centered communication. BMC medical education. 2018;18(1):266.

Laughey W, Sangvik Grandal N, Stockbridge C, Finn GM. Twelve tips for teaching empathy using simulated patients. Medical teacher. 2019;41(8):883–7.

Price-Haywood EG, Harden-Barrios J, Cooper LA. Comparative effectiveness of audit-feedback versus additional physician communication training to improve cancer screening for patients with limited health literacy. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(8):1113–21.

Lundeby T, Jacobsen HB, Lundeby PA, Loge JH. Emotions in communication skills training - experiences from general practice to Porsche maintenance. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(11):2141–3.

Haskard KB, Williams SL, DiMatteo MR, Rosenthal R, White MK, Goldstein MG. Physician and patient communication training in primary care: effects on participation and satisfaction. Health psychology : official journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association. 2008;27(5):513–22.

Oladeru OA, Hamadu M, Cleary PD, Hittelman AB, Bulsara KR, Laurans MS, et al. House staff communication training and patient experience scores. J Patient Exp. 2017;4(1):28–36.

Weiland A, Blankenstein AH, Van Saase JL, Van der Molen HT, Jacobs ME, Abels DC, et al. Training Medical Specialists to Communicate Better with Patients with Medically Unexplained Physical Symptoms (MUPS). A Randomized, Controlled Trial. PloS one. 2015;10(9):e0138342.

Berkhof M, van Rijssen HJ, Schellart AJ, Anema JR, van der Beek AJ. Effective training strategies for teaching communication skills to physicians: an overview of systematic reviews. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;84(2):152–62.

Saypol B, Drossman DA, Schmulson MJ, Olano C, Halpert A, Aderoju A, et al. A review of three educational projects using interactive theater to improve physician-patient communication when treating patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Rev Esp de enferm Dig. 2015;107(5):268–73.

Luthy C, Cedraschi C, Pautex S, Rentsch D, Piguet V, Allaz AF. Difficulties of residents in training in end-of-life care. A qualitative study. Palliat Med. 2009;23:59–65.

Hulsman RL, Ros WJ, Winnubst JA, Bensing JM. The effectiveness of a computer-assisted instruction program on communication skills of medical specialists in oncology. Med Educ. 2002;36(2):125–34.

Manning B, Sauereisen S, Last A, Matheus R, Slaymaker E, Jozwiak BJ. Teaching health communication in a family medicine residency program: report of a work in progress. Hospital Physician. 2006;42(2):47–54.

Maatouk-Burmann B, Ringel N, Spang J, Weiss C, Moltner A, Riemann U, et al. Improving patient-centered communication: results of a randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99(1):117–24.

Page M, Crampton P, Viney R, Rich A, Griffin A. Teaching medical professionalism: a qualitative exploration of persuasive communication as an educational strategy. BMC medical education. 2020;20(1):74.

Szmuilowicz E, Neely KJ, Sharma RK, Cohen ER, McGaghie WC, Wayne DB. Improving residents’ code status discussion skills: a randomized trial. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(7):768–74.

Junod Perron N, Nendaz M, Louis-Simonet M, Sommer J, Gut A, Baroffio A, et al. Effectiveness of a training program in supervisors’ ability to provide feedback on residents’ communication skills. Adv Health Sci Educ. 2013;18(5):901–15.

Schell JO, Cohen RA, Green JA, Rubio D, Childers JW, Claxton R, et al. NephroTalk: Evaluation of a Palliative Care Communication Curriculum for Nephrology Fellows. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2018;56(5):767–73.e2.

Litauska AM, Kozikowski A, Nouryan CN, Kline M, Pekmezaris R, Wolf-Klein G. Do residents need end-of-life care training? Palliative Supportive Care. 2014;12(3):195–201.

Slort W, Blankenstein AH, Schweitzer BP, Deliens L, van der Horst HE. Effectiveness of the ‘availability, current issues and anticipation’ (ACA) training program for general practice trainees on communication with palliative care patients: a controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;95(1):83–90.

Levine OH, Dhesy-Thind SK, McConnell MM, Brouwers MC, Mukherjee SD. Code status communication training in postgraduate oncology programs: a needs assessment. Curr Oncol. 2020;27(6):607–13.

Murphy E, Elder A. Ethics and communication in a high-stakes postgraduate examination. Medicine. 2016;44(10):623–5.

Berlacher K, Arnold RM, Reitschuler-Cross E, Teuteberg J, Teuteberg W. The impact of communication skills training on cardiology Fellows’ and attending Physicians’ perceived comfort with difficult conversations. J Palliat Med. 2017;20(7):767–9.

Lau FL. Can communication skills workshops for emergency department doctors improve patient satisfaction? J Accid Emerg Med. 2000;17(4):251–3.

Yudkowsky R, Alseidi A, Cintron J. Beyond fulfilling the core competencies: an objective structured clinical examination to assess communication and interpersonal skills in a surgical residency. Curr Surg. 2004;61(5):499–503.

Stiefel F, de Vries M, Bourquin C. Core components of communication skills training in oncology: a synthesis of the literature contrasted with consensual recommendations. European journal of cancer care. 2018;27(4):e12859.

Jameel A, Noor SM, Ayub S. Survey on perceptions and skills amongst postgraduate residents regarding breaking bad news at teaching hospitals in Peshawar, Pakistan. JPMA The Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association. 2012;62(6):585–9.

Abu Dabrh AM, Murad MH, Newcomb RD, Buchta WG, Steffen MW, Wang Z, et al. Proficiency in identifying, managing and communicating medical errors: feasibility and validity study assessing two core competencies. BMC medical education. 2016;16(1):233.

Furstenberg S, Schick K, Deppermann J, Prediger S, Berberat PO, Kadmon M, et al. Competencies for first year residents – physicians’ views from medical schools with different undergraduate curricula. BMC medical education. 2017;17(1):154.

Bradley KE, Andolsek KM. A pilot study of orthopaedic resident self-assessment using a milestones’ survey just prior to milestones implementation. Int J Med Educ. 2016;7:11–8.

Heath JK, Dine CJ. ACGME milestones within subspecialty training programs: one Institution’s experience. Journal of graduate medical education. 2019;11(1):53–9.

Brauch RA, Goliath C, Patterson L, Sheers T, Haller N. A qualitative study of improving preceptor feedback delivery on professionalism to postgraduate year 1 residents through education, observation, and reflection. Ochsner J. 2013;13:322–6.

Moss F. Writing is an essential communication skill: let’s start teaching it. Postgrad Med J. 2015;91(1076):301–2.

Renting N, Gans RO, Borleffs JC, Van Der Wal MA, Jaarsma AD, Cohen-Schotanus J. A feedback system in residency to evaluate CanMEDS roles and provide high-quality feedback: exploring its application. Medical teacher. 2016;38(7):738–45.

Essers G, van Dulmen S, van Es J, van Weel C, van der Vleuten C, Kramer A. Context factors in consultations of general practitioner trainees and their impact on communication assessment in the authentic setting. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;93(3):567–72.

Watmough SD, O’Sullivan H, Taylor DCM. Graduates from a reformed undergraduate medical curriculum based on Tomorrow’s Doctors evaluate the effectiveness of their curriculum 6 years after graduation through interviews. BMC Med Educ. 2010;10:65.

Burt J, Abel G, Elmore N, Campbell J, Roland M, Benson J, et al. Assessing communication quality of consultations in primary care: initial reliability of the global consultation rating scale, based on the Calgary-Cambridge guide to the medical interview. BMJ Open. 2014;4(3):e004339.

Fujimori M, Shirai Y, Asai M, Akizuki N, Katsumata N, Kubota K, et al. Development and preliminary evaluation of communication skills training program for oncologists based on patient preferences for communicating bad news. Palliat Support Care. 2014;12(5):379–86.

Han PKJ, Keranen LB, Lescisin DA, Arnold RM. The palliative care clinical evaluation exercise (CEX): an experience-based intervention for teaching end-of-life communication skills. Acad Med. 2005;80(7):669–76.

Duong PH, Zulian GB. Impact of a postgraduate six-month rotation in palliative care on knowledge and attitudes of junior residents. Palliat Med. 2006;20:551–6.

Gulbrandsen P, Jensen BF, Finset A, Blanch-Hartigan D. Long-term effect of communication training on the relationship between physicians’ self-efficacy and performance. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;91(2):180–5.

Ishikawa H, Son D, Eto M, Kitamura K, Kiuchi T. The information-giving skills of resident physicians: relationships with confidence and simulated patient satisfaction. BMC medical education. 2017;17(1):34.

Downar J, Knickle K, Granton JT, Hawryluck L. Using standardized family members to teach communication skills and ethical principles to critical care trainees. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(6):1814–9.

Wouda JC, van de Wiel HB. The communication competency of medical students, residents and consultants. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;86(1):57–62.

Daniels VJ, Harley D. The effect on reliability and sensitivity to level of training of combining analytic and holistic rating scales for assessing communication skills in an internal medicine resident OSCE. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(7):1382–6.

Aspegren K, Lønberg-Madsen P. Which basic communication skills in medicine are learnt spontaneously and which need to be taught and trained? Medical teacher. 2005;27(6):539–43.

Ju M, Berman AT, Hwang WT, Lamarra D, Baffic C, Suneja G, et al. Assessing interpersonal and communication skills in radiation oncology residents: a pilot standardized patient program. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;88(5):1129–35.

Matthews MG, Van Wyk JM. Exploring a communication curriculum through a focus on social accountability: a case study at a south African medical school. African Journal of Primary Health Care and Family Medicine. 2018;10(1):a1634.

Turner JW, et al. “Resident reflections on resident-patient communication during family medicine clinic visits.” Patient Educ Couns. 2020;103(3):484–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2019.09.011.

Reinders ME, Blankenstein AH, van Marwijk HW, Knol DL, Ram P, van der Horst HE, et al. Reliability of consultation skills assessments using standardised versus real patients. Med Educ. 2011;45(6):578–84.

Fallowfield L, Jenkins V, Farewell V, Solis-Trapala I. Enduring impact of communication skills training: results of a 12-month follow-up. Br J Cancer. 2003;89(8):1445–9.

Winward ML, Lipner RS, Johnston MM, Cuddy MM, Clauser BE. The relationship between communication scores from the USMLE step 2 clinical skills examination and communication ratings for first-year internal medicine residents. Academic medicine : journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges. 2013;88(5):693–8.

Gwyther L, Rawlinson F. Palliative medicine teaching program at the University of Cape Town: integrating palliative care principles into practice. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2007;33(5):558–62.

Scoles PV, Hawkins RE, LaDuca A. Assessment of clinical skills in medical practice. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2003;23:182–90.

Daley F, Bister D, Markless S, Set P. Professionalism and non-technical skills in radiology in the UK: a review of the national curriculum. BMC research notes. 2018;11(1):96.

Essers G, van Dulmen S, van Weel C, et al. Identifying context factors explaining physician's low performance in communication assessment: an explorative study in general practice. BMC Fam Pract. 2011;12:138. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-12-138.

Bård FJ, et al. “Effectiveness of a short course in clinical communication skills for hospital doctors: results of a crossover randomized controlled trial (ISRCTN22153332).” Patient Educ Couns. 2011;84(2):163–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2010.08.028.

Bosse HM, Nickel M, Huwendiek S, Jünger J, Schultz JH, Nikendei C. Peer role-play and standardised patients in communication training: a comparative study on the student perspective on acceptability, realism, and perceived effect. BMC Med Educ. 2010;10:27.

Taylor DC, Hamdy H. Adult learning theories: implications for learning and teaching in medical education: AMEE guide no. 83. Med Teacher. 2013;35(11):e1561–72.

Knowles MS, Holton EF, Swanson RA. The adult learner: the definitive classic in adult education and human resource development. Burlington: Routledge; 2012.

Kolb DA. Experiential learning: experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall; 1984.

Norcini J. Is it time for a new model of education in the health professions? Med Educ. 2020;54(8):687–90.

Ten CO, Taylor DR. “The recommended description of an entrustable professional activity: AMEE Guide No. 140.” Medical Teach. 2020:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2020.1838465.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to dedicate this paper to the late Dr. S Radha Krishna whose advice and ideas were integral to the success of this study.

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors (XHT MAF SLHL MBXYL AMCC JZ MC LKRK) were involved in research design and planning, data collection and processing, data analysis, results synthesis, manuscript writing and review and administrative work for journal submission. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

NA

Consent for publication

NA

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Appendix 1.

PubMed Search Strategy.

Additional file 2: Appendix 2.

Tabulated summaries and quality assessment of included articles.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Tan, X.H., Foo, M.A., Lim, S.L.H. et al. Teaching and assessing communication skills in the postgraduate medical setting: a systematic scoping review. BMC Med Educ 21, 483 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-02892-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-02892-5