Abstract

Due to the increased willingness of retail banking customers to switch and churn their banking relationships, a question arises: Is it possible to win back lost customers, and if so, is such a possibility even desirable after all economic factors have been considered? To answer these questions, this paper examines selected determinants for the recovery of terminated customer–bank relationships from the perspective of former customers. This study therefore evaluates for the first time, empirically and systematically with reference to a German Sparkasse as a case-study setting, whether lost customers have a sufficient general willingness to return (GWR) a retail banking relationship. From our results, a correlation is shown between the GWR a banking relationship and some specific determinants: seeking variety, attractiveness of alternatives and customer satisfaction with the former business relationship. In addition, we show that a customer’s GWR varies depending on the reason for churn and is surprisingly greater when the customer defected for reasons that lie within the scope of the customer himself. Despite the case-study character, however, our results provide relevant insights for other banks and, in particular, this applies to countries with a comparable banking system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

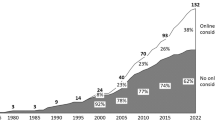

The financial sector is undergoing fundamental change. Growing regulatory requirements and a decade of low interest rates have eroded the proven business model of German banks. Additional regulatory capital requirements and a branch network that still covers the entire country are putting pressure on bank operating costs. Market penetration by new players with innovative financial solutions (FinTechs and TechFins) is leading to increased competitive pressure on established banks. Traditional branch operations are losing importance in the digital age (Bundesverband deutscher Banken 2017a). This development is also reflected by consolidation within the German banking system. The number of banks in Germany fell from 2,128 to 1,717 in the period 2009–2019, while the number of bank branches fell from 41,009 to 28,384 over the same period (Bundesverband deutscher Banken 2020). Every year, about 40 smaller banks disappear from the market, mostly through mergers. The majority of bank closures affect the mutual savings bank sector (Oliver Wyman 2018).

In this dynamic market environment and amid changing customer expectations, building long-term, profitable client–bank relationships are proving to be increasingly challenging. Every other bank customer already has a checking account with a competitor in addition to a main account at their first bank (Dziggel et al. 2018). This situation has led to declining customer loyalty in the retail business of many banks. A consequence is the increased willingness of customers to change banks (Bain & Company 2012). Around 30% of all bank customers can imagine switching away from their current bank in the future (Dziggel et al. 2018), so even intensive customer retention efforts cannot completely prevent customer churn. More than ever before, bank customers who were once bound to a provider or a brand are pursuing the (economic) optimization of their contracts, products or services. To this end, they are continuously using the possibilities of the Internet, for example, to find banking products with better prices or quality via comparison platforms (Pick 2017). At the same time, switching banks is easier today than in the past. The statutory account switching service in Germany enables consumers to choose a new bank at a manageable cost (Kunz 2016).

If banks remain inactive in this new competitive environment, according to Drummer et al. (2016), they could lose approximately 30–40% of their revenues through customer churn and margin erosion. Customer termination of the business relationship is usually associated with negative effects on sales and earnings and always results in a deterioration in market position. To compensate for the loss of revenue and market share, banks primarily acquire new customers who lack experience with the products and services offered and whose potential purchasing behaviour is frequently unknown. Due to the lack of experience and the often necessary use of monetary incentives, acquisition measures are all the more lengthy and cost-intensive. An alternative strategy that has been largely neglected up to now–but may promise success in such a dynamic environment–is attempting to win back migrated customers with whom a bank already has a track record and a purchasing history (Kumar et al. 2015; Neu & Günter 2015).

Strategic measures to win back customers, also known as customer recovery, have so far received little attention in the retail banking literature. There is little research on customer recovery in the banking sector, and most of it dates back to the first decade of this century (e.g. Bruhn & Michalski 2001; Sieben 2002; Michalski 2002). The same is true for banking practice. Especially in comparison with the management of prospective customers and customer loyalty, customer recovery management is underdeveloped. This raises the question of whether retail banks should engage in win-back initiatives. However, before a bank can initiate recovery activities to win back migrated private customers, it must implement a systematic customer recovery process. Against the background of required investments, the question arises as to the chances of success for customer recovery management in retail banking.

In this regard, we lay the groundwork for strategic decisions on the organisational implementation of customer recovery management. To this end, we examine the rationality of resuming a previous business relationship from the perspective of former bank customers. This study therefore evaluates for the first time, empirically and systematically, with reference to a German savings bank (Sparkasse) case study, whether lost customers have a sufficient general willingness to return (GWR) a retail banking relationship.Footnote 1 As a consequence, our study may initiate a potential shift from the prevailing strict prioritisation of new customer acquisition to the implementation of a systematic customer recovery management.

We derive three research questions from this discussion:

-

1.

For what reasons do retail customers terminate their retail banking business relationships, and can banks have an influence on those factors as a way to win back customers?

-

2.

How pronounced is the willingness of migrated private customers to return in the previous business relationship?

-

3.

How do selected factors influence the willingness to return in a customer–bank relationship?

This paper analyses the reasons for churn and GWR as an indicator for the chances of success of a management process to win back customers in the retail banking sector. Our results show that a correlation exists between the GWR and several specific determinants: seeking variety, attractiveness of alternatives, and customer satisfaction with the former business relationship. In addition, we provide indications that a customer’s GWR varies depending on the reason for churn and is greater when the customer defected for reasons that lie within the scope of the customer himself. While we do not claim (empirical) generalizability to all banks, our results can provide valuable evidence not only for savings banks but also for the other two bank types, private banks and cooperative banks (credit unions) in the German three-pillar system or banks in comparable international banking systems (e.g. Austria).

Our paper is structured as follows. Section 2 presents the conceptual principles of customer recovery management and relates them to retail banking. The research hypotheses are then derived based on concrete research questions against the background of existing literature. Section 3 explains the data and methodology of the empirical study. Section 4 presents the results and their interpretation. Section 5 concludes with a summary of the main findings and presents some limitations of our case study.

Theoretical framework and hypothesis development

The current situation in retail banking

The retail banking activities in Germany are currently characterised by a highly dynamic phase of ongoing change in existing market structures (Oliver Wyman 2018). In addition to merger-related churn, the financial sector is witnessing a general decline in customer loyalty in its retail business. The majority of bank customers would not recommend their current bank to friends. However, a view of individual groups of institutions reveals significant differences. While large institutions, savings banks, and cooperative banks are losing popularity, loyalty has increased towards direct banks (Bain & Company 2012). At the same time, FinTechs as well as direct banks without branch networks benefit from both cost efficiency and cost transparency compared with the established retail banks. Automated and IT-supported processes can reduce costs, especially for financial products that do not require explanation, and pass the remaining costs on to consumers (Niehage 2016).

This dynamic development is triggering a change in the characteristics and behaviour of bank customers. Technological developments combined with the homogeneity of the essential components of banking products have led to increasing market transparency (Dinh & Greve 2010) and higher price sensitivity of customers (Dziggel et al. 2018). In addition, customer demands in terms of speed and convenience are increasing. If customers do not get what they want, they seize the opportunity to change banks much more quickly than before (Kinting and Wißmann 2016). One-third of Germans have already changed their bank (Bundesverband deutscher Banken 2017b), and approximately 30% of all bank customers no longer rule out a change of their primary banking relationship in the near future (Dziggel et al. 2018). On average, bank customers have already chosen another bank 1.73 times. The frequency of changing banks is thus only slightly below that of changing telecommunications providers, where the provider has been changed an average of 1.98 times (Pick 2017). Presently, just under 40% of all bank customers conduct their banking business at exclusively one bank. Additional secondary bank facilities now account for about 40% of customer value.Footnote 2 If a partial churn gradually leads to complete termination of the business relationship, the value of the banking relationship will erode to almost zero in the long term. The economic damage to the industry is projected to be around 8 to 10 billion euros over the next five years (Dziggel et al. 2018).

Regulatory frameworks further facilitate the decision to migrate. Up to now, written notice of termination has been the dominant channel for terminating the business relationship (Pick 2017). The legal obligation of banks to assist in switching accounts (§§ 20 ff. ZKGFootnote 3) and Payment Service Directive II, which has been in force since 2016, have further reduced the barriers to changing banks. The switching process has become much easier through a reduction in the bureaucratic and financial burdens on customers (Kunz 2016; Dziggel et al. 2018).

A representative study by the Bundesverband deutscher Banken (2017b) revealed that the main reasons for bank customers to enter into a business relationship with another financial services provider are the pricing of an account (31%) and dissatisfaction with the service (33%). Although the overall level of relationship satisfaction is high, with a score of 84% (28% are ‘very satisfied’ and 56% are ‘satisfied’), dissatisfaction with individual product or service features will lead to churn. This finding is confirmed when considering the different levels of satisfaction at respective banks. Enthusiastic customers are predominantly found at direct banks. Especially, banks offering free account management achieve the highest satisfaction values and exceed customer expectations. Two out of three customers would most likely recommend their direct bank to others (Lindenau 2017).

However, the level of customer satisfaction on its own is not a sufficient indicator of customer churn. The desire for variety—referred to in the literature on behavioural theory as ‘variety-seeking’—can also lead to churn (Bruhn and Boenigk 2017). There is empirical evidence that a change of products, services or suppliers alone can benefit the consumer. This benefit is not related to churn due to dissatisfaction. Accordingly, the underlying motivation for the pursuit of variety is not influenced by the brand or the new provider (Helmig 1997; Peter 1999). In retail banking, the increasing importance of variety-seeking can be seen in the growing number of secondary bank connections.

An additional reason for customer churn is change of residence, which is of great importance, especially for regional banks with geographically limited business activities. For nearly one-third of customers who have already changed their bank at least once, relocation was the decisive reason for the change (Bundesverband deutscher Banken 2017b). If the change of residence exceeds a certain distance, the customer often changes to a bank located in the new place of residence. At the same time, any attempt to prevent churn is de facto limited if the bank follows the regional principle that restricts business activities outside a certain region (Riekeberg 1995).

In an early investigation of the financial services sector, Michalski (2002) reported a fundamental willingness by former bank customers to return in an earlier business relationship. Michalski also noted a positive time-lag effect and found that the willingness to return increases over time. This is due to a changed situation or a reassessment of the reason for churn, which makes a return to the former provider appear more attractive. Sieben (2002) examined the factors influencing recovery success in the banking sector. The process of winning back customers and the personal interaction between the customer and the bank are decisive for successful customer recovery.

Customer recovery management in retail banking

The business relationship between the customer and the bank is a dyadic, membership-like service relationship. A contractual business relationship exists between the customer and the bank. The bank provides a service that is usually available on a continuous basis (Adler 2003). The duration of the customer relationship is positively related to profitability. The longer a customer receives the company's services, the greater the customer value (Neu & Günter 2015). As the term of the business relationship increases, sales increase and cross-selling and upselling potentials can be exploited. At the same time, the price sensitivity of the customer lessens. With churn, these advantages of the business relationship are lost (Homburg et al. 2003). Due to the intangible nature of the services, trust-related aspects are the primary factors that determine the purchasing decisions of bank customers. Trust is created by experiences with repeated personal interaction or from a constant quality of service and existing customer satisfaction over a long period of time (Bruhn 2016). Since building experience and trust is time-consuming (Bruhn 2016) and acquiring new customers is relatively costly (Sieben 2002), banks in retail banking should also consider customer recovery management initiatives (Bruhn & Michalski 2001). A successful recovery avoids the acquisition cost to replace a former customer (Homburg et al. 2003; Neu & Günter 2015).

In addition, the indirect, partly qualitative benefits of preventive information gathering and damage minimisation should be considered. An intensive survey and analysis of the reasons for the loss of customers provide valuable information about a bank’s operational performance weaknesses. Active measures to identify the causes of customer churn are an important basis for customer-oriented improvement processes and can prevent future churn (Büttgen 2003). Thus, preventive information gathering is an important aspect of customer recovery management. Negative word of mouth from dissatisfied customers who migrate can cause additional turnover losses. A successful win-back can support the goal of minimising market damage. If this does not succeed, an attempt must be made to end the lost customer relationship and minimise negative communication (Sauerbrey & Henning 2000). The probability of a successful winning-back depends on, among other things, the reasons for customer churn, which must be analysed (Seidl 2009).

Such a churn analysis helps in understanding the scope of and reasons why customers leave an existing business relationship with their bank (Sieben 2002). Banks should carry out a differentiated identification for each individual customer regardless of whether the entire business relationship or only certain services have been terminated. Once lost customers and the extent of churn have been identified, professional customer recovery management must determine the reason why the churn occurred (Homburg et al. 2003). The underlying causes of customer loss can be used to derive key findings for churn prevention and the probability of recovery. First, the information gained serves to avoid future errors and optimise services (Büttgen 2003). Second, the reasons for churn can be systematised according to the degree to which they can be influenced, thereby providing information on the probability of recovering a former customer. Consequently, the bank can determine which customer losses are basically avoidable and can segment and evaluate migrated customers (Neu & Günter 2015).

According to prior literature, few banks implement individual measures to reactivate lost bank customers. For the few banks that know the exact number of reactivated customers, recovery rates vary between 1 and 10% (Bruhn and Michalski 2001). Sieben (2002) confirms this statement in his empirical study and finds a rate of recovery of former bank customers of about 10% per year. The study also analyses the profitability of the measures used and their cost–benefit ratio. Overall, recovery costs in the financial services sector amount to 74 euros per successful recovery on average. Of this, the cost of personnel accounts for 75%. In relation to efforts to acquire new customers, the costs are lower by a factor of 3.8 (Sieben 2002). However, in practice, most banks do not have any effective controls in place. Less than a quarter of banks regularly monitor the success of such measures once implemented (Bruhn & Michalski 2001). The few financial services institutions that have information report a return on customer recovery of 41%. This puts banking well behind other industries, such as the automotive and retail sectors, which report returns of 102% and 60%, respectively (Homburg & Schäfer 1999).

Determinants of customer recovery management in retail banking

Strategic triangle

With regard to retail banking, we use the so-called strategic triangle to systematise reasons for churn. The triangle consists of three dimensions—company, competition, and customer—and thus classifies the reasons for churn into company-, competition-, and customer-related factors (Michalski 2002; Pick 2017).

Company-related or ‘pushed-away’ reasons refer to the product and service range of the previous company and the dissatisfaction associated with it. From the customer's perspective, there are deficiencies in the company's performance, such as poor product quality, too high price levels, and regional gaps. In addition to rational reasons, factors such as perceived incompetence or unfriendliness of employees also play a role (Dinh & Greve 2010). The knowledge of these reasons can help to eliminate existing deficits and serve to identify customer-specific compensation services for pushed-away customers.

Competition-related (‘pulled-away’) reasons refer to customer switching due to attractive communication by the competition or due to competitors actively enticing customers away. From the customer's point of view, the competitor's services are more attractive in terms of quality or price. Creating an awareness of these reasons can contribute significantly to the optimisation of competitive position.

Finally, customer-related (‘broken-away’) reasons, such as marriage, divorce or change of job, can also lead to a decision to leave. Other examples of changes in a customer’s private or professional life include death, change of residence or loss of demand. In addition, psychological motives, such as variety-seeking,Footnote 4 can lead to churn. Information about the customer-related reasons for churn helps to prevent hopeless customer win-back initiatives (Sauerbrey & Henning 2000; Michalski 2002; Büttgen 2003).

Bruhn and Michalski (2001) performed a survey of the three reasons for churn according to the strategic triangle in an exploratory study of banks. In the category of company-related churn, the change of a personal contact was found by the surveyed banks to be the central reason for churn. In second place comes dissatisfaction with price along with product deficiencies. Problems in internal processes or service are also important. Location gaps, in contrast, are among the least important reasons for churn. The competition-related reasons are dominated by the activities of competitors who directly entice bank customers. As a new competitive factor that has been added in recent years, the activity of FinTechs is also playing an increasing role. Through innovative banking services, they motivate traditional bank customers to change (Pick 2017). In the category of customer-related churn decisions, in addition to death as a natural reason for terminating a business relationship, change of residence plays a particularly important role. Variety-seeking is of only minor importance for churn (Bruhn & Michalski 2001).

Michalski (2002) examined the relationship between company-, competition- and customer-related reasons for churn from the point of view of bank customers. Here, too, the company-related reasons were the most important factors in the decision to migrate, accounting for 52.5% of mentions. It is in this category that customer dissatisfaction is highest. Negative experiences in customer contact dominate here and affect the interaction between employees and customers. A bank's terms and conditions are also highly relevant for a churn decision. For 28.0% of the sample, customer-related motives are a reason to terminate the business relationship with the bank. Causes in this category mainly concern reorganisation of existing accounts, e.g. due to marriage or a change of residence. At 19.5%, competition-related reasons are of subordinate importance. Churn in this category is primarily due to more attractive conditions offered by competitors. In particular, the free account management of other banks is an important reason for changing providers (Michalski 2002).

To conclude, past empirical studies show that in retail banking, company-related reasons are the main cause of customer churn from the perspective of both the banks and the customers. We therefore also assume in our study that, for example, despite significant digital transformation processes in the banking industry and resulting changes in the competitive environment, company-related reasons continue to be the main motivational driver for customers’ churn. However, we would like to investigate whether this hypothesis still holds after around 20 years, when many of the past empirical studies for the German market were conducted. Therefore, we formulate the following hypothesis:

H1

Company-related reasons are the most important customers’ motivation for their churn.

Willingness to return

The existence of a willingness to return is the starting point for any strategic customer recovery (Pick 2008). Customer recovery management can be successful only if former customers are generally motivated to actually return in a terminated business relationship (Pick & Krafft 2009). A seminal preparatory work for the concept of willingness to return is the study by Bendapudi and Berry (1997). They cluster influencing factors for maintaining a relationship based on compulsion or desire into four categories: environment, company, customer and transaction (Bendapudi and Berry 1997). Rutsatz (2004) uses the approach of Bendapudi and Berry (1997) in customer loyalty management as a basis for the investigation of a trust- and desire-based resumption of the relationship with the previous provider. According to Rutsatz (2004), customer motivators for a return include satisfaction with the former provider and evaluation of market alternatives. On a conceptual level, Rutsatz (2004) distinguishes between general and specific willingness to return. This differentiation is adopted by Pick (2008) in an empirical study on the resumption of contractual business relations in order to establish for the first time a definition and conceptualisation of the various terms. Pick (2008) examines the willingness to return in a contractual business relationship using the example of a transport service provider and a publishing house. The general willingness to return (GWR) is defined as the customer's unconditional readiness, independent from corporate activities, to return in a contractual business relationship with a previous provider (Pick 2008) and can be interpreted as a fundamentally positive attitude of a customer towards the previous provider (Pick 2008). Conditional or specific willingness to return, in contrast, depends on concrete company activities and reflects the customer's expectations of measures to be taken by the company to win back the customer (Pick 2008). Special offers should be used since customers who have migrated—despite a general willingness to return—usually do not return on their own and have certain expectations of win-back initiatives. Conditional willingness to return is thus the final driver for the actual return of migrated customers and requires the existence of a GWR (Pick & Krafft 2009).

GWR is in line with the theory of cognitive dissonance. According to the theory of dissonance (Festinger 2012), individuals generally evaluate the decisions they have made as well as their implementation. The decision to return in a previous business relationship is made on a customer-specific and rational basis by weighing the advantages and disadvantages. As people strive for consistency in their decisions, intentions and behaviour, GWR can be linked to the actual activities in the context of the resumption. Pick et al. (2016) show a statistically significant positive influence of GWR on actual recovery as well as on the duration of the second customer relationship. This means that actual win-back activities are not the only trigger for resumption. The conclusion is that companies should first understand the general willingness of their former customers better before making concrete recovery offers.

In practice, there is considerable interest in allocative control of recovery measures. Special activities should only be implemented when customers are sufficiently willing to return. Companies are interested in finding out how certain customer characteristics and the nature of the previous business relationship influence willingness to return (Rutsatz 2004). In the field of retail banking, however, there is little research to date on determinants of former customers' willingness to return.

Desire for variety

The behaviouristic construct of variety-seeking is a customer-related determinant of GWR. A behavioural explanation for the search or desire for variety can be found in the theory of cognitive dissonance (Peter 1999). If an individual is looking for new experiences or has a feeling of saturation in the existing business relationship, this can cause a cognitive imbalance through perceived dissonance. Subsequently, reduction measures are taken to restore the inner balance. Consequences may include migrating from the existing business relationship (Pick 2008).

As a starting point for the pursuit of variety, Adler (2003) identifies distinct problem-solving needs in continuous financial services. Customers of a bank may have several accounts at different banks that satisfy different banking needs, such as processing of payment transactions, securities trading or long-term financing. Homburg and Giering (2001) refer to a product-related, intrinsically motivated search for variety and detect a negative effect on customer satisfaction. This reinforces the assumption in the literature that customers change suppliers only because of a desire for variety regardless of their satisfaction with the product. Sieben (2002) notes that customer desire for variety in the banking segment has a strongly negative, significant influence on actual recovery success. This could be due to the fact that customers terminate a bank relationship solely out of interest in something new. In such a case, any recovery measures would be largely unsuccessful because there is no GWR on the part of the customer. However, to date, there exists no empirical study of the effect of variety-seeking on GWR. Based on the above considerations, we hypothesise that the need for variety correlates negatively with GWR:

H2

The desire of variety-seeking influences negatively the individual GWR

Relationship satisfaction

Satisfaction with the previous business relationship is a company-related determinant of the GWR. Detecting unsatisfied customers already during the service encounter enables retail banks to immediately address service failures, help to start recovery actions early and, thus, reduce customer churn (Baier et al. 2021). Satisfaction can be defined as the result of a cognitive comparison (Homburg & Stock-Homburg 2016). By maximising customer satisfaction and thus avoiding cognitive dissonance, the risk of churn can be reduced and a positive effect on customer retention and loyalty can be achieved (Töpfer & Mann 2008). With churned customers, there is a chance that dissonances can be found if there was a high satisfaction previously. It is possible that the dominant reason for churn is perceived as irrelevant after a certain period of time (e.g. a change in private life situation). The decision to terminate the contract is then re-evaluated and, if necessary, revised. Dissonances that arose from an in retrospect erroneous decision to terminate a bank relationship can now be reversed. Thus, the satisfaction with the former business relationship has a positive influence on the dissonance reduction by resuming the former business relationship (Pick 2008).

In the financial services industry, the customer–bank relationship is of a long-term nature. The assessment is based on a comparison of the expected performance from the business relationship and the actual experience with the bank and its products. The result is a satisfaction rating for the customer–bank relationship (Eickbusch 2002). Lohmann (1997) notes in a study of customer–bank relationships that satisfaction with banking services makes the greatest contribution to explaining customer loyalty in the financial services sector. Based on the understanding that bank customers usually have several reasons for churn (Keaveney 1995; Michalski 2002) it seems reasonable to consider the concept of relationship satisfaction as cumulative satisfaction of the customer with the entire previous business relationship.

While Michalski (2002) finds no significant correlation between customer satisfaction and willingness to return in the banking sector, Sieben (2002), Homburg et al. (2007) and Pick (2008) confirm for other industries a significantly positive influence of the previous satisfaction on the success of win-back initiatives and the GWR. Also Knox & van Oest (2014) show in their study the relationship and emphasise in particular the role of complaints from customers as an important indicator. Kamboj et al. (2022) show the connection between mobile banking failures and customer satisfaction and the very sensitive relationship here to what extent failures can also directly affect customers’ satisfaction in a digital environment. We therefore hypothesise that satisfaction with the previous business relationship and GWR are positively related:

H3

The satisfaction with the previous business relationship is positively related to the individual GWR.

Attractiveness of alternatives

A competition-related determinant is the attractiveness of the alternatives. According to dissonance theory, the availability and perceived attractiveness of alternative options influence the extent of dissonance. The higher the customer assesses the attractiveness of the alternatives, the greater the cognitive dissonance (Festinger 2012). If it is not possible to cognitively justify the existing business relationship by changing one’s attitudes, a dissonance may only be dissolved by a change in provider (Pick 2008). For this purpose, the current business relationship is evaluated by the customer and serves as a benchmark to assess the benefits of potential alternatives. If the customer feels better or at least not worse off by switching to an alternative provider, the intention to migrate is created. If, in contrast, there are no better alternatives on the market, there is a certain dependency on the current supplier (Henseler 2006, 55–56). Additionally, an unfavourable cost–benefit of perceived alternatives can lead to an unsatisfactory business relationship being maintained, as it is not worth changing providers (Bendapudi and Berry 1997; Colgate & Lang 2001).

In retail banking, customers choose their bank based on individual criteria and their personal expectations. Due to the large number of alternative banks and the pronounced homogeneity of the banking services offered, customers face a selection problem and focus on objectively comparable characteristics. If expectations are met or even overfulfilled after a change in the bank, customers see their choice confirmed. If the expectations are not met, however, a cognitive dissonance arises, which offers the former provider a chance to reacquire customers (Mihm 1999). Prices as an observable measure for comparison play an important role in assessing the attractiveness of alternatives. In retail banking, high acquisition premiums are now also used to attract customers.

Pick (2008) shows for the transport services and media industry that a high perceived attractiveness of competing offers has a negative effect on the GWR, regardless of the actual use of alternative offers. Accordingly, the GWR decreases with the increasing attractiveness of the alternatives. We assume that due to the intense competition and high price sensitivity, this connection can also apply in principle to retail banking. We therefore hypothesise the following relationship between the attractiveness of the alternatives and the intention to switch back:

H4

The attractiveness of the alternatives negatively influences the individual GWR.

Customer-related features

Product-independent characteristics of customers play an important role in forecasting the success of customer recovery initiatives (Naß 2012). Trubik and Smith (2000) find that the gender as a variable cannot contribute to better identification of defecting customers. Rutsatz (2004) confirms this result and finds no significant connection with the willingness of former customers to return, which also applies to bank customers (Michalski 2002).

Another empirically investigated characteristic is age. Athanassopoulos (2000) finds that with the increasing age of private bank customers, their loyalty to the company increases. The risk of churn decreases accordingly. A higher age also has a positive effect on the success of customer recovery initiatives (Homburg et al. 2007). They conclude that it is more difficult for older customers to adapt to new products and that they are therefore more willing to return to a known supplier. For the GWR, Pick (2008) identifies conflicting results for the investigated transport service industry and the media industry. While customers of publishers show an increasing GWR with higher age, the results for the transport service providers point in the opposite direction. For banks, the study by Michalski (2002) shows no significant differences between customers who are willing to return and those who are not willing to return with regard to their age. In conclusion, the results from the service sector in general, however, at least provide a tendency that the age of the customers could have a positive influence on the GWR.

The socio-economic criterion of income is also part of the debate in the scientific literature on customer recovery management. Michalski (2002) shows that bank customers with a high net household income also have a higher willingness to return in a former business relationship. For reasons of effectiveness, it would therefore seem appropriate to limit the customer recovery initiatives to high-income customer segments. Pick (2008) on the other hand, finds no positive correlation between household income and GWR among the customers of the transport service industry. However, the results at least provide a tendency that the high net income of the customers could have a positive influence on the GWR.

In retail banking practice, the socio-demographic characteristics of age and the socio-economic characteristic of income in particular are very often used for market segmentation and customer typology as they can be easily collected (Eickbusch 2002; Koot 2005). Due to the ambiguous results of previous empirical studies on age or income and their effect on customer recovery success, we aim at identifying differences in the GWR in retail banking with respect to age and income. If such differences were detected, customer recovery initiatives could be shaped to address the most promising customer segment. Based on the contradictory findings to date, the following undirected hypotheses are to be analysed:

H5

The customer’s age influences positively the individual GWR.

H6

The customer’s net income influences positively the individual GWR.

Reasons for customer churn

Referring to the strategic triangle, the reasons for termination expressed by customers indicate a different probability of returning and are thus determinants for the success of recovery (Naß 2012). Homburg and Schäfer (1999) identify customers who have a latent need for the product and service offerings of the previous provider. If customers defected for reasons beyond a firm’s control, then these should be negligible in the context of recovery management. Conversely, the probability of regaining defected customers increases with companies being able to influence the reasons for their churn. While company-related reasons are initiated by the banks themselves and thus can be controlled to a large extent, competition-related reasons for churn can be influenced to only a limited extent. Likewise, customer-related reasons such as situational or psychological reasons for customers to migrate can usually hardly be influenced by the bank (Michalski 2002; Homburg et al. 2003). Following these findings and taking the perspective of bank management, it can be assumed that the probability of recovery is highest for company-related causes of customer churn. This is followed by competition-related reasons with a medium probability of recovery, while the lowest probability of recovery should be assumed for customer-related reasons (Bruhn & Boenigk 2017).

The degree to which a bank is able to influence churn factors may, however, differ from the individual intentions of customers. In this investigation, we aim at detecting a link between the reasons for customer churn and the intention to return in the business relationship. Customers who have ended their relationship with a bank may have done so for personal reasons and not because of company-related shortcomings. Factors that can influence a customer's decision to return include the reason for their original defection, such as a move to a new location, and the level of satisfaction they had with the bank before they left. In general, customers who left for personal reasons, such as marriage, divorce or change of job, may have a higher willingness to return to the bank once their situation changes and they are able to re-establish the banking relationship. Conclusively, we postulate the following hypothesis:

H7

The existence of customer-related reasons for customer churn positively affects the GWR.

Data and methodology

This study analysed defected customers of a small- to medium-sized Sparkasse as a case-study analysis. We use the case-study approach to create an in-depth understanding of GWR in a real-life context (Gerring 2004; Seawright & Gerring 2008; Helm et al. 2022). The case-study methodology is based on describing, understanding, predicting and evaluating. Therefore, that research approach can clearly highlight the potential added value of a more comprehensive customer recovery management in the retail banking sector (Woodside 2010; Helm et al. 2022). Case studies are able to apply the analysed cases as a starting point for inductive theory development and also for innovations in the customer relationship management (Eisenhardt & Graebner 2007; Helm et al. 2022).

The Sparkasse considered in the investigation is a decentralised financial services institution with about 45,000 private accounts in 2018. The sample covers account closures from 01 January 2017 to 31 May 2019. The selection of the time span considered the positive time-lag effect identified by Michalski (2002), according to which GWR increases over time. Our sample covers only private customers in retail banking who derive their income predominantly from employment. For our analysis, the closure of the current account was regarded as the termination of the business relationship. Accordingly, GWR for the reopening of a private current account was levied.

For the selection of test persons, the account terminations in the period mentioned were first examined for relevance. A prerequisite for efficient customer recovery management is that the customers considered should be only those with whom there is a fundamental probability of recovery and who can be expected to engage in a profitable business relationship in the future, in view of the fact that our paper is intended to provide a general overview of the general chances of success of a customer recovery management system.

Account closures due to death were generally excluded from the sample. In terms of account closures by age, the highest churn rates are found among customers aged 31 to 45 years (31.1%). Also relevant are the figures of 26.9% for those 18 to 30 years old and 28.1% for customers between 46 and 64 years of age. The relative churn rates for customers younger than 18 years and older than 65 years, on the other hand, are significantly lower. Our analysis therefore excludes account closures by customers younger than 18 and older than 65 years of age.

As a further criterion, the bank account type before the termination was considered. Customers who had a purely deposit-based basic account due to a previously negative credit performance were not considered. It was assumed that banks are not interested in re-establishing the business relationship with these customers. Account closures that led to a merger with other existing accounts and thus did not result in the termination of the business relationship were also excluded. In order to only investigate customer-initiated terminations by private customers, business relationships terminated by the bank were also not considered. Closures of joint accounts were not included as we aim at examining GWR on an individual customer basis.

Finally, a further exclusion from our data set resulted from legal reasons. Former customers may be contacted only by post. However, this is permitted only if this communication channel has not been expressly objected to. Therefore, customers who have negated their consent to data protection for postal communication or who are registered in the ‘Do Not Call’ registry (Robinson registry) also had to be excluded in advance.

In total, 1815 former customers were identified, taking into account the exclusions listed above (see Table 1). In terms of the selected socio-demographic variables, our data set is representative of the entire customer base of the considered Sparkasse.

A standardised written questionnaire was used to determine the reasons for customers' churn and is presented in Table 9. When designing the questionnaire, we took care not to make content-related correlations directly obvious to the interviewee, in order to minimise the bias from common method variance (CMV) as much as possible. We follow the principle of Harrison et al. (1996) and their cognitive miser principle. However, we cannot completely exclude the bias due to CMV, but we are also aware of the critical discussion about the impact of this bias (see, e.g. Chang et al. 2010; Posdsakoff et al. 2003; Crampton & Wagner 1994; Lindell & Whitney 2001; Spector 2006).

The questionnaire was made available via two different media, online and by post. Former customers may be contacted only by post. In order to increase the response rate, the postal version included an envelope for free return and the provision of the findings was offered. Participation in the survey was possible for 2 weeks from 15 June 2019 to 30 June 2019. A pretest was carried out with regard to the design of the questionnaire and its operationalisation.

The survey offered predefined response options and included 16 items in four thematic question blocks. Question block 1 focussed on the reasons for churn as well as on the process of terminating the relationship. In block 2, questions aimed at measuring the attitude of customers. Block 3 investigated the potential conditions for returning in the business relationship. The survey concluded with socio-demographic and economic questions about the person in block 4 of questions. Table 2 lists the reasons for customer churn that were investigated.

In order to confirm that there are usually several reasons for termination, multiple selection was allowed. The second question was then used to identify the main reason for terminating the business relationship in case of several reasons. Items 3–8 refer to the termination process and provide additional information on the chances of success of customer win-back initiatives. A binary question about the main bank details is used to find out how many core customers have terminated the business relationship. The fourth item provides information on whether the customers who left the bank articulated their reason for termination and thus offered the bank the opportunity to avert termination in advance. Item 5 refers to the termination procedure (personal termination, written termination or via the new bank). Items 6 and 7 provide indications of the extent to which customer recovery management activities have already been carried out by the bank without a systematic process. Item 8 serves the purpose of churn analysis and provides insights into which competitor has convinced the customer to migrate.

Question block 2 serves to collect the variables ‘general willingness to return in the business relationship’, ‘variety-seeking’, ‘satisfaction with the previous business relationship’ and ‘attractiveness of alternatives’. For the selection of suitable items, we use the operationalisation of Pick (2008). For the four constructs, a 5-point Likert scale with named end points was used for the measurement of the settings. The end points of the scale were named according to the respective indicators and the individual scale points were numbered for better orientation. To avoid the central tendency, a ‘no indication’ option was additionally provided. This additional option thus enables a distinction to be made between actually indifferent or ambivalent opinions and unwanted statements.

Question block 3 features the optional and open question 13, ‘under what specific conditions would you open an account with the savings bank again?’ This serves to obtain additional information, whether a GWR would exist at all.

Questions 14–16 on socio-demographic and socio-economic data serve as differential analysis and represent the fourth block of questions. In order to test the research hypotheses, age and income ranges were formed. The age was surveyed on an ordinal scale and categorised into the three relevant ranges 18 to 30 years, 31 to 45 years and 46 to 64 years according to the customer types at the savings bank in question.Footnote 5 Like age, net income was surveyed at an ordinal level and grouped in income ranges (customer segments). Customers are segmented into a net income of less than €1000, between €1000 and €1750, between €1750 and €2250 and above €2250.

Hypothesis H1 is tested by means of the relative frequency distribution of the categorised reasons for churn. We use a correlation analysis to test the bivariate correlation hypotheses H2, H3 and H4. The aim is to quantify the correlations between the GWR and the three selected determinants for the likelihood of success of customer win-back initiatives. Due to the equidistance generated, the Likert scale can be interpreted as a quasi-metric scale and the data collected can be treated as an interval scale (Theobald 2017).

For the characteristics examined, it is assumed that there is a linear relationship between the GWR and the respective influencing variables of variety-seeking, satisfaction with the previous business relationship and attractiveness of the alternatives. Following Cohen (1988), we consider it as a low or weak correlation at |r| ≈ 0.10, a medium or moderate correlation at |r| ≈ 0.30 and a high or strong correlation at |r| ≈ 0.50. For the differential analysis of hypotheses H5, H6 and H7, a univariate, single-factor analysis of variance is performed due to the different scale levels of the variables to be investigated.

Figure 1 shows the conceptual framework of the empirical analysis as well as the relationship between questionnaire and the measurement of the latent variables GWR, variety-seeking, satisfaction with the previous business relationship and attractiveness of the alternatives. The latent variable variety-seeking is measured by item battery 9 with 5 items (questions) in the questionnaire. The latent variable satisfaction with the previous business relationship is represented by item battery 10 with 4 items. The latent variable attractiveness of the alternatives is measured by item battery 11 with 5 items. Finally, the latent variable GWR is measured by item battery 12 with 4 items in the questionnaire. Also indicated in the figure is which relationship is represented by which hypothesis and which direction of charge is to be expected based on the formulated hypotheses. The reliability of the item batteries (Cronbach’s α) is always at an uncritical level.

Conceptual framework for our analysis with the three selected determinants of the general willingness to return (‘variety-seeking’, ‘satisfaction with the previous business relationship’ and ‘attractiveness of alternatives’) as well as the relationship between formulated hypotheses and the assumed direction of influence. The variable α represents the Cronbach’s α value

Table 3 summarises the related literature for the derivation of our hypotheses.

Results and discussion

Results

A total of 1798 of 1815 former customers were reached in the survey, as 17 respondents did not receive the questionnaire because of invalid address data. In total, 282 people took part in the survey during the survey period. This corresponds to a response rate of 15.7%, comprising 144 (51.1%) online participants and 138 (48.9%) postal returns. A total of 7 respondents had to be sorted out due to incomplete data. As a result, a final sample of 275 respondents was generated for the study. The final sample, in terms of the socio-demographic variables considered in the survey, is representative of the entire customer base of the Sparkasse under consideration. Table 4 summarises the description of the sample based on the personal characteristics of the respondents.

Overall, the sample is largely balanced for individual characteristics (max. ± 10 percentage points) as there is no clear overrepresentation of individual characteristic values within the groups. Nevertheless, we do not claim our sample to be representative of the entire banking market. However, we do not see major obstacles why our results might not be relevant for other retail banks in the German three-pillar banking system.

In the course of the churn analysis, a total of 606 reasons were given for the termination of the account, which represents an average of 2.2 reasons for churn per lost customer. The dominant reason for churn is dissatisfaction with the price for the account. For 48.0% of test persons, this reason was the decisive factor for terminating the contractual relationship. Change of residence is also of high importance with 22.5% of the mentions, which is not surprising given the prevailing regional concept of savings banks in Germany. For 7.3% of participants, a change in life situation played a role in termination, while 5.1% of test persons were persuaded to change their bank account by a competitive offer from another bank. Accessibility (0.0%) has no relevance, and the various other mentioned reasons for churn shown in Fig. 1 have only marginal relevance, ranging from 0.4% to 2.9%. Other reasons account for 5.1% of the responses. Figure 2 provides an overview of the main reasons for churn.

Applying the selected categorisation according to the strategic triangle, company-related reasons for churn dominate with 60.9% of all mentions. 32.2% of the respondents, terminate the relationship for customer-related reasons, while competition-related reasons account for only a small share (6.9%). We can therefore confirm hypothesis H1 that company-related reasons dominate in contrast to competition- and customer-related reasons.

When focussing on the individual customer types and segments, different characteristics become apparent. Figure 3 shows the characteristics in relation to age and net income.

With increasing age and net income, company-related reasons gain in importance and the relevance of customer-related reasons for termination decreases. Among 18 to 30 years old customers, company-related reasons are only important for about half (51.1%) of the respondents. In contrast, customer-related (38.6%) and competition-related (10.2%) reasons for termination are quite pronounced in this age group. Among customers aged 31 to 45 and 46 to 64, respectively, the churn was mainly due to negative experiences with the company (64.6% and 67.5%) and customer-related churn plays a minor role (31.3% and 26.0%).

The four customer segments show a similar picture. While customer and competition-related reasons predominate among the customers with the lowest income (51.8%), deficiencies in company performance are the dominant cause of churn in the other segments. Competition-related reasons are the least pronounced among customers with a net income between €1000 and €1750 (1.4%), but they increase significantly with rising net incomes at the expense of customer-related churn. Among customers with a net income above €2250, customer-related reasons (25.7%) are the least significant for terminating a business relationship.

Of participants in the survey, 89.8% had used the terminated account as their primary bank facility. The reason for terminating before the explicit termination was communicated by 40.0% of customers. The remaining 60.0% terminated the business relationship without prior notification. This result is consistent with their chosen termination method. Of the total test persons, 45.5% had their accounts closed directly by the new bank without any possibility of interaction. Another 19.6% preferred to terminate the account in writing and avoided personal contact with the bank. About one-third (34.9%) offered the possibility of direct interaction when they personally visited the branch to close the private account. In only 41.5% of cases was the reason for termination queried by an employee of the bank, and in 47.6% of the sample, no reasons were collected for why the customer had terminated the banking relationship. Another 10.9% could not remember whether they were asked about the reasons for leaving. It is noteworthy that only every fifth customer (21.1%) reported that their bank had made an attempt to save the relationship after the customer had communicated an intention to terminate their account. In 68.7% of cases, no attempt was made at all to avoid termination. The remaining 10.2% do not remember.

In Table 5, we present the correlation matrix between the constructs of variety-seeking, satisfaction with previous business relationships, the attractiveness of alternatives and the GWR. The arithmetic mean (x̅) for the GWR of all survey units is 2.28 with a standard deviation (s) of 1.02. Of the three determinants examined, satisfaction with the previous business relationship has the highest positive correlation value with 0.274 and is highly significant (x̅ = 3.76, s = 0.97), followed by the construct variety-seeking (x̅ = 2.66, s = 1.05) with 0.209. Attractiveness of the alternatives (x̅ = 3.23, s = 0.92) has a negative correlation but is also highly significant. We can also provide a highly significant semi-strong negative correlation between the construct’s satisfaction and attractiveness of the alternatives what is intuitively not surprising.

Based on our results from Table 5, we provide a multiple regression analysis whose results can be observed in Table 6. The multiple regression analysis is applied with GWR as a dependent variable and variety-seeking, satisfaction and attractiveness of alternatives as independent variables. Our model can (adj. R2, 0.105) explain the GWR and is highly significant. All independent variables have a significant influence on the GWR whereas the influence of attractiveness of alternatives is negative and has the lowest significance. There is no indication of multicollinearity because the variance inflation factors (VIFs) are very low (< 5).

Our hypothesis H2 postulates a negative influence between variety-seeking and GWR, i.e. the greater the desire for variety, the lower the GWR. Contrary to this assumption, the analysis shows a positive influence (0.17), so that H2 does not apply. With hypothesis H3 a positive influence between satisfaction with the previous business relationship and the GWR was formulated. The results confirm this assumption. Satisfaction with the previous business relationship shows a positive influence on the GWR and is highly significant. Hypothesis H4, which postulates a negative relationship between the attractiveness of the alternatives and the GWR, also applies. However, the influence is rather low only still significant. However, our model provides evidence that the variables variety-seeking, satisfaction and attractiveness of alternatives explain the value of GWR.

The basis for the evaluations of hypotheses H5 to H7 is the individual characteristic values of the metrically measured GWR. The data collected for women (x̅ = 2.26, s = 1.03) and men (x̅ = 2.29, s = 1.01) were checked using the t test. No statistically significant difference between the genders was found (t(266) = − 0.245, p > 0.05), which is in alignment with the results of Trubik and Smith (2000) and Rutsatz (2004) and will not be further discussed. The measured values for the factors age and net income are shown in Table 7.

Hypothesis H5 postulates that GWR varies depending on age. With an average value of 2.37, the highest incidence of GWR is among customers aged 18–30 years. In contrast, the lowest value is found among customers aged 46–64 years (x̅ = 2.12), which indicates that the GWR decreases with increasing age. However, the results for the variable age are not statistically significant. With regard to the socio-economic criterion income, hypothesis H6 assumed that the GWR varies in relation to net income. The results indicate a decreasing GWR with increasing net income. However, just like for the variable age, the differences are not statistically significant.

Finally, hypothesis H7 postulated that the GWR would vary depending on the reason for churn, and that, in particular, customer-related reasons for churn have a positive effect on the GWR. The survey data from the churn analysis were taken up and categorised according to the strategic triangle (see Table 8).

The results show the lowest GWR for company-related churn (x̅ = 2.12, s = 0.92), followed by competition-related churn (x̅ = 2.28, s = 0.97) and the highest value for customer-related churn (x̅ = 2.48, s = 1.06). The mean values for GWR differ significantly for the various categorical reasons for churn, which confirms the conjecture that the reasons for churn influence the GWR. We can confirm hypothesis H7 that customer-related reasons positively affect the GWR.

Discussion

Reasons for churn

In total, four of the seven hypotheses were confirmed and provide significant results (H1, H3, H4 and H7). Hypothesis H1, which states that banks lose customers more often for company-related reasons than for competitive and customer-related reasons, can be confirmed in principle. The churn analysis shows that there are usually several reasons why customers defect. For retail banking, this implies that the decision to defect is not made on the basis of individual points of criticism or events, but that there are several reasons for the final decision. Instead of an impulsive decision, e.g. based on one-off negative events, the churn is more likely to be based on a rational choice. This can also be seen in the dominance of price dissatisfaction as the pivotal reason for terminating the relationship. Almost half of the bank customers have churned because of the fee for managing the account. This confirms a high price sensitivity of bank customers and consequently leads to a questioning of loyalty to banks that charge fees for an account. If the termination is due to a competitive offer that includes an attractive account price, this conclusion is even reinforced. It may be questionable, however, how sustainable these tempting prices will be for the customer in the course of the new business relationship. The enticing competitors could engage in price dumping and lure customers without being able to justify these offers on a lasting basis with their own cost structure.

As our findings show, other company-related factors that can be influenced, such as dissatisfaction with account services or poor quality of service or advice, are not relevant for terminating a business relationship. Findings of other studies that list poor service quality as a reason for churn (Bundesverband deutscher Banken 2017b) could not be confirmed in this investigation. The closure of branches and the change of contact person are also not reasons worth mentioning, which is understandable against the background of the changed importance of the bank branch in the digital age. A personal contact person is needed only in exceptional cases and not for everyday banking transactions such as the processing of payment transactions. Most services can be handled via online banking or banking apps. The branch is mainly used as a contact point for cash supply. Since it is now also possible to withdraw cash from providers outside the industry, such as grocery stores, the closure of branches is not a relevant reason for churn. Customers do not seem to miss the bank branch. This is all the more true if the trend towards cashless payments continues in Germany. Furthermore, if personal advice is required, it is now also possible to obtain it by telephone or via digital media such as chats or video conferencing.

Competition influences customer churn to only a small extent. Instead, it is an individual decision. Advertising measures or personal inquiries from competitors only lead to churn when the offer is convincing. Comparison portals on the Internet support this process and take over the previously costly price and performance comparison for bank customers.

With regard to customer-related reasons, private customers who are less price-sensitive migrate mainly due to a change of residence or a change in life situation. One reason for this is the regional principle that limits the business area of the bank or savings bank. Although, on the basis of technological possibilities, the processing of payment transactions is possible independent of time and location, many bank customers still have a need for a local bank. This is to a certain extent contradictory to the insight that the branch is often regarded as a mere cash supply point by the customer. Taking a closer look, this may be due to the customer's desire for security in the event of an urgent and short-term need for personal advice. Furthermore, it was found that the desire for variety is not noteworthy. One explanation may well be the increased number of secondary accounts. Assuming that another secondary account already existed some time before the closure of the main bank account, the search for variety was no longer decisive for the account closure due to existing experience.

Characteristics of customers

With regard to customer characteristics, it was found that with increasing age and net income, company-related churn becomes more important. The company-related reasons are significantly less relevant for the decision to terminate a contract in the case of customers between 18 and 30 years of age and customers with an income of up to € 1,000 than is the case with older customers and net income above that level. At the same time, these customer groups have a particular affinity for competitive offers. With regard to the dissatisfaction with the price as the main reason for churn, they are therefore more willing to pay a fee for account management. In practice, it is often assumed for this customer segment that young customers migrate mainly because the fee waiver for their account no longer applies. However, our findings show that price dissatisfaction is not necessarily the decisive reason for churn. The reasons why customers aged 18 to 30 change banks more often for customer-related reasons could be the fact that they have not yet determined their centre of life and experience frequent private changes during this phase of life (e.g. job change, family planning). The results show that the account fee is a problem for all customer groups, in particular for customers greater than 30 years of age. Price-strategic considerations should therefore be applied to all customers. From the view of banks with regard to their loss of income in the event of churn, income from account fees should be rather substituted by cross-selling, especially for customers aged above 30 years, who often have a longer business relationship and higher incomes.

An essential part of customer recovery management is to identify the reasons for churn and to initiate appropriate measures to avoid future churn for reasons that can be influenced. However, the chances of this happening are becoming increasingly slim. With today's technical resources and the simplified switching process, the barriers to entering into a new banking relationship have fallen significantly. Our results also show that almost half of all account closures are now initiated by the new bank. A possible explanation could also be a certain shame on the part of the customers. Customers do not want to find themselves in the situation of reporting their intention to switch or enter into a possible confrontation. As the results also show, only 40% of customers contact their bank in advance of terminating their relationship, thus enabling direct interaction before termination. Although this provided at least partial information about the threat of termination, for only one in five terminations was an attempt made to keep the customer. One reason could be the lack of an internal company process. The bank employees do not have the necessary competence to take concrete countermeasures.

Influences on GWR

Evaluating the usefulness of implementing customer recovery management in retail banking, the investment costs required for this must be compared with the chances of success. Overall, the general willingness to recover former banking relationships can be assessed only as low. Once customers have migrated, the chance that the decision made will be subsequently revised is limited.

On the basis of cognitive dissonance theory, three determinants were identified which were suspected to be related to the GWR. According to the theoretical findings, it was assumed that cognitive processes after the decision to leave the bank make the option of returning to the former bank probable in principle (Rutsatz 2004; Pick et al. 2016). The desire for variety is mediocre with an average score of 2.66 across all former customers. Some of the customers seem to like trying new things, while others prefer consistency. The negative correlation assumed with hypothesis H2, that a highly pronounced desire for variety leads to a lower GWR, could not be found. A possible explanation for the positive effect on GWR can be the high degree of standardisation in everyday banking transactions. The cognitive effort for the decision to switch is relatively limited, since the risk of a wrong decision is significantly lower due to the homogeneous services. A real ‘change’ is not to be expected from the customer's point of view, at least not among the established banks. The one clear differentiation is in pricing. It can therefore be assumed that customers whose desire for variety is more pronounced tend to compare prices and services even after they have decided to switch. The positive and highly significant correlation with the GWR may be an indication that former customers will reconsider former providers in future comparisons and give them a second chance. Against the background that customers were not primarily dissatisfied with other features of the business relationship, this assumption is reinforced.

In the analysis of the relationship between satisfaction with the previous business relationship and the GWR, we found a positive correlation (hypothesis H3). Specifically, it was found that the former customers had a relatively high overall satisfaction with the terminated business relationship with a measured value of 3.76, which corresponds to industry averages (Bundesverband deutscher Banken 2017b). As it turns out, satisfaction alone is not a sufficient condition in retail banking to prevent churn. Dissonances that lead to termination cannot be completely prevented by mere satisfaction without enthusiasm. Looking again at the results of the churn analysis, it is mainly price dissatisfaction and customer-related reasons, which are largely detached from satisfaction, that are relevant for churn. Although the company's efforts to ensure, for example, a high quality of service and advice, continuous contact persons or customer-friendly complaint management lead to satisfied customers overall, they are not sufficient to inspire ambivalent customers in the long term. It is the product-related dissatisfaction, specifically with the account fee, that overshadows existing relationship satisfaction and leads to churn. The direct banks show that free account management can lead to enthusiasm (Lindenau 2017). In accordance with the findings of Michalski (2002) customers differentiate between relationship-oriented overall satisfaction and partial satisfaction or dissatisfaction with individual product features. Of the determinants examined, satisfaction with the previous business relationship shows the strongest correlation with the GWR. This leads to the conclusion that although the general satisfaction with the retail bank cannot prevent customers to defect, it is positively related to the GWR to the former provider. Relationship satisfaction thus forms the basis for effective win-back initiatives.

The importance of competing offers for customer recovery management is reflected in the perceived attractiveness of the alternatives, which correlates negatively with the GWR. For hypothesis H4 it was found that the GWR decreases with increasing attractiveness of the alternatives. This initially logical, negative correlation is weak, however. The mean value of 3.23 indicates that the competing offers are generally considered attractive. Here, too, an influence of the account fee can be assumed in the customer's evaluation. Among the competition-related reasons, special offers from competitors were the key reason for switching. This could have led to the fact that the evaluation was mainly price-driven, which seems plausible considering the fierce price wars for private customers with a simultaneously homogeneous range of services.

The analyses of age and income groups carried out to test hypotheses H5 and H6 did not reveal any statistically significant differences in the GWR. Our results indicate that segmentation according to the criteria of age and income, which have been widely used in customer loyalty management at banks to date, does not appear dominant in the context of customer recovery management. Since the GWR is a necessary condition for the actual recovery, the design of specific win-back initiatives depending on age or income does not seem to be a target-oriented solution either.

Significant differences with regard to the GWR, on the other hand, become apparent when considering the categories of the main reasons for churn (hypothesis H7). Our results are contrary to the postulated assumptions of earlier studies, according to which the identified reasons for churn can be used as indicators for estimating the probability of recovery (Michalski 2002; Homburg et al. 2003; Naß 2012; Neu & Günter 2015; Bruhn & Boenigk 2017). If the business relationship was terminated for customer-related reasons, a low or no probability of recovery would be assumed. However, this customer group has the highest actual intention to return. In contrast, the GWR is statistically significantly lower if company-related reasons caused the customer to defect. This finding has far-reaching consequences in view of the fact that reasons for churn can be influenced. While unsatisfactory performance on the part of the bank can be remedied, at least in principle, this is mostly not the case with private reasons for termination. It can be concluded from this that a subsequent remedy of the internal performance problems that lead to churn offers only limited opportunities to win back former customers. Due to the predominant price dissatisfaction, the customers who have migrated do not seem to assume that this factor will be adjusted promptly, which is reflected negatively in their willingness to return, even despite a high level of satisfaction with the entire previous business relationship.

In the case of customer-related churn, the GWR is significantly higher, but the customer-specific reasons for the decision can rarely be influenced by the bank. Since the main reason for customer-related churn is the change of residence, the regional principle proves to be an obstacle that is almost impossible to overcome for regional banks. Although these customers are more willing to reopen an account with the former bank, this is not possible due to the territorial restrictions. It is therefore not possible to win back customers who have completely migrated. In the event of a partial churn, an attempt could be made to retain customers, by using the advantages of online and mobile banking to process payment transactions. However, such services are rarely cost-covering for the bank, and customers are more likely to contract higher margin services requiring intensive advice from the new bank on site. Under these circumstances, winning back former customers who have changed their place of residence is also not a viable solution for regional banks.

Conclusion

The aim of this study based on a case-study approach is to provide a theoretical classification of customer recovery management in the retail banking industry and to provide indications for strategic decisions on the organisational implementation of this management process. To date, customer recovery management has played a subordinate role in the relationship marketing activities of banks, although the prerequisites are available. The resources required to implement a recovery process in retail banking must first be justified on the basis of the chances of success from a customer perspective. The use of specific win-back initiatives can be successful above all if there is a GWR among the lost customers.

In this study, it was found that company-related reasons for churn predominate in retail banking. The most significant in this category is dissatisfaction with the price of account management. One finding in this context is that customers between 18 and 30 years of age and customers with an income of up to €1000 are more willing to pay a fee for account management than is the case with older customers and those with higher incomes. Price dissatisfaction can basically be cured by the bank by accepting the economic consequences. Customers who are less price-sensitive, however, often migrate due to a change of residence or a private change in their life situation.

For evaluating the chances of success of a customer recovery management we used the concept of a relationship’s GWR. This fundamentally positive attitude of former customers is in line with the dissonance theory and can be seen as a major driver for the actual return to the former provider. The GWR is a general prerequisite for the success of concrete win-back initiatives within the framework of customer recovery management. As our findings show, there is a moderate GWR with former retail banking customers. A review of the segmentation criteria of age and income, which are common in retail banking, did not reveal any significant differences in the GWR of former customers. By contrast, diverse results were found when the reasons for churn were examined. If bank customers migrated for personal reasons, GWR is significantly higher than if the business relationship was terminated for company-related reasons. This result is contrary to the ability to influence the reasons for churn and thus limits the probability of customers to return.