Abstract

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a disease continuum from pathophysiologic, biomarker and clinical perspectives. With the advent of advanced technologies, diagnosing and managing patients is evolving.

Methods

A systematic literature review (SLR) of practice guidelines for mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and AD dementia was performed following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). This systematic literature review (SLR) aimed to summarize current clinical practice guidelines for screening, testing, diagnosis, treatment and monitoring in the AD continuum. The results of this SLR were used to propose a way forward for practice guidelines given the possible introduction of biomarker-guided technology using blood- or plasma-based assays and disease-modifying treatments (DMTs) targeted for early disease.

Results

53 clinical practice guidelines were identified, 15 of which were published since 2018. Screening for asymptomatic populations was not recommended. Biomarker testing was not included in routine diagnostic practice. There was no consensus on which neurocognitive tests to use to diagnose and monitor MCI or AD dementia. Pharmacologic therapies were not recommended for MCI, while cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine were recommended for AD treatment.

Discussion

The pre-2018 and post-2018 practice guidelines share similar recommendations for screening, diagnosis and treatment. However, once DMTs are approved, clinicians will require guidance on the appropriate use of DMTs in a clinical setting. This guidance should include strategies for identifying eligible patients and evaluating the DMT benefit-to-risk profile to facilitate shared decision-making among physicians, patients and care partners.

Conclusion

Regular evidence-based updates of existing guidelines for the AD continuum are required over the coming decades to integrate rapidly evolving technologic and medical scientific advances and bring emerging approaches for management of early disease into clinical practice. This will pave the way toward biomarker-guided identification and targeted treatment and the realization of precision medicine for AD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Advancements in the late-stage clinical development of disease-modifying treatments (DMTs) for Alzheimer's disease (AD), coupled with the emergence of new DMTs, necessitate a significant paradigm shift in the early detection, diagnosis and management of AD. This shift requires updates to clinical practice guidelines to align with the latest developments |

This study presents a systematic literature review (SLR) of current clinical practice guidelines for screening, diagnosis, monitoring and treatment recommendations for the AD continuum with a focus on identifying key areas for future advancements |

Clinical practice recommendations for the AD continuum have remained largely consistent and unchanged across various countries and global regions over the past 2 decades, with no recommendations for screening or biomarker testing for asymptomatic populations and pharmacologic treatment for cognitive symptoms only recommended for those with AD dementia |

The study offers a critical assessment of the current state of practice guidelines and proposes a roadmap for innovative strategies to transform the field, particularly in light of the anticipated clinical application of biomarker-guided technology using blood or plasma assays and targeted DMTs for early-stage disease |

Regular evidence-based updates to existing guidelines for the AD continuum are essential to integrate rapidly evolving technologic and medical advances. This will bring emerging approaches for early disease management into clinical practice, paving the way for biomarker-guided identification, targeted treatment and the realization of precision medicine for AD in the coming decades |

Introduction

Medical guidelines, also knowns as clinical practice guidelines, aim to guide decisions on diagnosis, management and treatment in specific areas of healthcare [1]. Unlike previous approaches that relied on tradition or authority, modern medical guidelines are rooted in evidence-based medicine [2]. One crucial aspect is that published medical guidelines should align with latest advances in early detection, differential diagnosis and patient management. Therefore, a task force composed of a government body (such as Ministry of Health), a medical specialist organization or a professional society should lead the development of medical guidelines.

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is now recognized as a continuum progressing from an early asymptomatic phase through a prodromal symptomatic phase, mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and ultimately to mild, moderate and severe dementia [3,4,5]. Alzheimer’s disease is characterized by the presence of biologic hallmarks, namely amyloid-β plaques and intracellular tau neurofibrillary tangles, that can be detected years before the onset of cognitive impairment or dementia symptoms. Biomarker tests for detecting amyloid and tau can identify AD pathophysiology before symptom onset, allowing for early detection [6].

Recently, treatment options for AD dementia were restricted to three approved cholinesterase inhibitors (donepezil, galantamine and rivastigmine) and one N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor antagonist (memantine), available in markets including the USA, Europe, South Korea and Japan. Clinical trials of cholinesterase inhibitors demonstrated symptomatic effects in AD and are prescribed to patients in mild to late stages of AD dementia [7].

Disease-modifying treatments (DMTs) for AD are being developed with diverse targeting mechanisms, including amyloid, tau, inflammation and synaptic plasticity/neuroprotection [8, 9]. The primary aim of DMTs is to target the underlying pathophysiology at molecular, cellular and systems levels to slow progression of AD from MCI to mild dementia, or from mild dementia to severe dementia in early-stage patients [10]. This could extend the period before significant cognitive and functional decline and delay the loss of life quality, independence and the need for institutionalization and long-term care.

The late-stage clinical development of DMTs and emerging DMTs necessitate a substantial paradigm shift in the early detection, diagnosis and management of AD. Recent perspective and review articles and expert consensus or appropriate use statements offer guidance on detection and clinical management in preclinical or early disease, which may be necessary with the introduction of DMTs [6, 11,12,13]. These publications emphasize the need for a change in the treatment paradigm and updates to clinical practice guidelines for early disease.

This systematic literature review (SLR) aimed to identify and summarize current clinical practice guidelines for screening, diagnosis, monitoring and treatment in the AD continuum. In this article, we use the term screening to refer to routine assessment for AD in populations at risk of AD dementia who either do not have a formal diagnosis of cognitive impairment or have neurocognitive disorders but without a diagnosis of dementia. We use the results of this SLR to propose a way forward for practice guidelines as the patient journey evolves, given the possible introduction of biomarker-guided technology using blood- or plasma-based assays and DMTs targeted for early disease [6, 11,12,13].

Methods

Search Strategy

An SLR on EMBASE, MEDLINE, MEDLINE In-Process, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, PsycINFO and International Health Technology Assessment databases was conducted from inception date to April 12, 2022.

The search strategy combined free text and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) related to AD dementia and MCI populations, management, practice guidelines and exclusionary terms for unwanted publication types. Supplementary Material presents the full search strategies.

To identify clinical practice guidelines, keywords such as “dementia,” “Alzheimer’s disease” and “mild cognitive impairment” were searched on the Guidelines International Network library, Google search and six health technology assessment websites: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), Scottish Medicine Consortium, Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee, Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health, All Wales Medicines Strategy Group and Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER).

The search was not limited by date of publication, geographical location or language.

Study Selection

Two reviewers completed a two-level screening process following predefined inclusion and exclusions criteria. The first level involved screening titles and abstracts, and the second level involved a full-text review of studies included in level 1. In case of discrepancy between reviewers, a third researcher was consulted to achieve consensus. The inclusion and exclusion criteria, as well as the types of guidelines to be extracted, are detailed in Table 1.

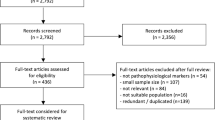

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors. All processes were fully documented in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Fig. 1) [14].

Extraction of Recommendations for Clinical Practice

After identifying clinical practice guidelines, recommendations for screening, testing and diagnosis, treatment and monitoring of MCI due to AD and AD dementia were extracted. One researcher performed data extraction, and another researcher verified all extracted data with original sources to ensure quality control. Recommendations extracted were those that focused on identification and treatment of those with AD-related cognitive impairment or dementia and not those that focused on identifying other possible causes of cognitive impairment or dementia.

Additional details were also recorded, such as the country of published guideline, year of publication, Google Scholar citation, procedure of establishing the guideline, scope, target population, level of recommendations, strength of evidence, organization name and conflicting interests.

If the guidelines had multiple versions, only the most recent one was extracted.

Full data extraction tables, including the methods used to develop the guidelines, for the 53 clinical practice guidelines identified are presented in the Supplementary Material, Tables A3 through A55.

Results

Selection of Guidelines

Details of the selection process are presented in Fig. 1, which resulted in the selection of 53 guidelines for data extraction. Extraction of the full set of 53 clinical practice guidelines is presented in the Supplementary Material. In this report, we focus on the most recently published guidelines (2018–2022), which coincide with or follow the publication of the National Institute on Aging and Alzheimer's Association (NIA-AA) Research Framework focused on a biologic definition of AD [15] (15 guidelines).

Fifteen guidelines since 2018 were examined [16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30]. Seven guidelines provided recommendations for populations with AD dementia [18, 19, 23,24,25,26, 28]. Three guidelines focused on MCI [20, 29, 30], but only the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) 2018 guidelines clearly stated “MCI due to AD” [20]. Five guidelines covered recommendations for both AD and MCI [16, 17, 21, 22, 27]. The guidelines were international [16, 18, 29] or were from the UK [23], US [20], Taiwan [17], India [21], Malaysia [27], Korea [22], Ireland [26, 28], Denmark [25, 30] and Australia and Canada [19, 24].

Methods of Developing Guidelines

The methods used to develop these guidelines varied. Seven used an evidence-based approach from the latest literature, although the methods were not clearly stated [16, 17, 21, 22, 25, 28, 30]. The International Clinical Practice Guideline of Chinese Medicine Alzheimer was based on clinical studies of traditional Chinese medicines (TCMs) and experts’ experience [18]. Five guidelines explicitly reported a comprehensive guideline development process, including panel selection, systematic review and evidence evaluation [19, 20, 24, 27, 29]. The Irish National Clinical Guidelines were derived from three high-quality existing guidelines [26], while the NICE guidelines were developed by a multidisciplinary committee that conducted an in-depth review of research evidence [23].

The study findings, including the characteristics of the guidelines published since 2018, including the target populations, are presented in Table 2, and a summary of the practice recommendations is presented in Table 3 and in the following sections. Many guidelines did not include specific inclusion criteria for the causes of MCI. The major differences between the guidelines published before 2018 and since 2018 are presented in the Supplementary Material.

Screening Recommendations

Four recent guidelines offer recommendations on screening [18, 20, 22, 27]. The AAN MCI 2018 guideline suggested how to screen for MCI relating to AD [20], the Korean dementia guidelines suggested how to screen for AD dementia in individuals with neurocognitive disorders [22], the Ministry of Health Malaysia (MOHM) dementia 2021 guidelines recommended whether to screen asymptomatic community-dwelling adults [27], and the International Clinical Practice Guideline of Chinese Medicine Alzheimer 2021 (TCM 2021 guidelines) suggested how to screen for asymptomatic populations at risk of progression to AD [18]. The AAN MCI 2018 guidelines advise clinicians to assess individuals for MCI and not assume that concerns about memory or impaired cognition were due to normal aging. The guidelines also advise clinicians to assess those with close contact who expressed concerns about memory or impaired cognition [20]. This is because MCI needs proper assessment to determine whether any causes of impairment were reversible and subjective complaints may indicate changes in cognitive function [20]. The AAN MCI 2018 also cautions that, to reduce overdiagnosis or underdiagnosis of MCI relating to AD, clinicians should not rely solely on historical reports of subjective memory concerns when assessing cognitive impairment during a Medicare Annual Wellness Visit [20]. For those who are appropriate for MCI screening or assessment, the guidelines advise using brief, validated screening instruments for MCI screening followed by additional formal assessments for those testing positive, as the brief tests may be insufficient [20].

In addition to the AAN MCI 2018 guidelines, three more recent guidelines provide screening recommendations [18, 22, 27]. The 2022 Korean dementia guidelines suggest administering the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) for dementia screening in individuals with neurocognitive disorders [22]. The TCM 2021 guidelines recommend that “for those with family history of illness, genetic tests should be taken as early as possible for early detection, prevention and treatment, and regular screening for people over 65 years old is recommended” as a prevention method [18]. The MOHM 2021 guidelines did not advocate screening asymptomatic community-dwelling adults because the balance of benefits and harms was not determined [27].

The recommendations for screening for MCI due to AD and AD dementia remain limited. Screening of asymptomatic populations or general populations with subjective memory impairment was not mentioned in any other of these recently published guidelines.

Testing and Diagnosis

Recent guidelines lack consensus on determining the severity of AD dementia. The guideline panels from three recent guidelines define the severity of AD dementia using several methods: (1) using MMSE scores (e.g., mild AD with scores ranging from 21–26, moderate AD with scores ranging from 10 to 20) [28], or (2) the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth edition and the International Classification of Diseases-Tenth Revision (ICD-10) [21, 27] or (3) a global staging instrument (e.g., Clinical Dementia Rating Scale, Global Deterioration Scale for Assessment of Primary Degenerative Dementia, Functional Assessment Staging) [21, 27]. The NICE dementia guidelines advise against relying solely on cognition scores to assess severity of AD dementia in inappropriate situations [23].

Nine recently published guidelines offer recommendations on testing and diagnosis [16, 20,21,22,23, 26,27,28, 30]. Testing and diagnosis of MCI were addressed by the AAN MCI 2018 and Danish MCI 2018 guidelines [20, 30]. Recommendations for testing and diagnosis of AD dementia were presented in three guidelines [23, 26, 28]. Other guidelines offer recommendations for both MCI and dementia [16, 21, 22, 27].

To evaluate individuals with suspected MCI or dementia, using brief cognitive tests is recommended, while considering other test results and the clinical context [20,21,22,23, 28, 30]. Validated cognitive instruments such as the 10-point cognitive screener, the 6-item cognitive impairment test, the 6-item screener, the Memory Impairment Screen, the Mini-Cog and Test Your Memory [23] are recommended by NICE; the Irish dementia guidelines suggest General Practitioner Assessment of Cognition, Mini-Cognitive Assessment Instrument and the Memory Impairment Screen, which were shown as efficient and convenient tools in a systematic review [28], and two guidelines recommend the widely used MMSE [21, 22]. Additionally, assessing activities of daily living (ADL) using ADL scales such as Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) or Everyday Activities Scale for India (EASI) is recommended by for those with suspected MCI or dementia in two guidelines [21, 30].

Two guideline panels considered offering biomarker testing to individuals with MCI to clarify the underlying cause of the cognitive impairment, but did not advocate the use for routine diagnosis [20, 30].

Before diagnosing AD in individuals with MCI or dementia, clinicians should exclude other diseases or conditions by offering structural imaging [23, 30]. AD confirmatory biomarker tests—including lumbar puncture and analyses of cerebrospinal fluid Aβ, total tau and phosphorylated tau [22, 23], fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-positron emission tomography (PET) [16] and perfusion single-photon emission computed tomography if FDG-PET is unavailable [23]—can be used for differential diagnosis to increase diagnosis accuracy. Imaging of AD focuses on molecular and metabolic targets (e.g., amyloid, tau and FDG uptake) and regional structural atrophy [16, 22, 23, 27, 30]. Structural neuroimaging can improve the sensitivity and accuracy of AD diagnosis by assessing the degree of medial temporal lobe atrophy and excluding reversible causes of cognitive decline and other intracranial pathology [16, 22, 23, 27, 30].

Testing of AD genes has not been considered in these recent guidelines.

For patients with dementia, a comprehensive assessment performed by a trained healthcare professional is recommended before offering any psychotropic medication [26].

Treatment

Of the most recently published guidelines, 12 presented recommendations for AD or MCI treatment and management [17,18,19,20,21, 23,24,25,26,27,28,29].

Regarding pharmacologic approaches, most guidelines recommend acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and memantine to improve cognitive symptoms for AD dementia treatment [17, 21, 23, 24, 27, 28]. Future treatment options such as monoclonal antibodies targeting AD-associated pathophysiologic mechanisms are also expected [17].

Appropriate use of antipsychotic drugs for treating behavioral and psychologic symptoms of dementia was extensively discussed in several guidelines [21, 25,26,27]. Nonpharmacologic approaches are recommended for patients with behavioral and psychologic symptoms of dementia [28]. Acupuncture, psychotherapy, behavioral therapy, diet therapy (e.g., Mediterranean-like diet) and other healthy lifestyles (e.g., reducing harmful drinking, tobacco cessation) may also reduce the risk of cognitive impairment and delay AD progression [17, 18, 27, 29]. The TCM guidelines recommend a combination of traditional Chinese medicines and acupuncture to treat syndromes induced by AD in the early stage [18].

No medications for cognition are advocated at the present for MCI because of lack of proven effective pharmacologic therapy [17, 20, 29]; the AAN MCI 2018 guidelines indicated that practitioners might choose to offer cholinesterase inhibitors [20].

Behavioral and neuropsychiatric symptoms should be assessed in individuals with MCI and treated with both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic approaches, as behavioral/psychiatric symptoms may be related to functional impairment and progression from MCI to dementia [20].

Similar to AD management, nonpharmacologic interventions such as physical activity, resistance training, cognitive training and healthy diets were recommended for MCI [17, 20, 29]. The AAN MCI 2018 guidelines based on 6-month studies indicated that twice-weekly exercise benefits and cognitive interventions could improve cognitive function in individuals with MCI [20]. Aerobic exercise showed a strong correlation with improved neuroprotective factors and executive function in the Taiwan 2021 guidelines [17]. The World Health Organization workgroups suggested limiting or stopping harmful drinking in individuals with MCI in light of strong observational evidence that alcohol is a risk factor for cognitive decline or dementia [29].

Monitoring

From the most recently published guidelines, six documents presented recommendations for monitoring MCI relating to AD or AD dementia progression [19, 20, 22,23,24, 28]. The Irish dementia guidelines recommended regular physical examination for people aged > 65 years [28]. The Korean dementia guidelines suggested monitoring the clinical development of older adults with subjective cognitive decline (SCD) by conducting periodic follow-ups every 1–2 years because those with SCD are more likely to develop dementia or AD dementia than those without SCD [22]. For MCI or dementia, frequent reviews of medications and cognitive status were recommended [20, 28]. For patients with AD, NICE recommended that acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibitors should not be stopped because of disease severity alone [23]. Deprescribing AChE inhibitors or memantine should be considered in some situations, with close periodic monitoring and re-initiation of medication if necessary [19, 24].

Discussion

The AD Continuum Practice Guidelines: Current Status

The pre-2018 and post-2018 practice guidelines share similar recommendations for screening, diagnosis and treatment (see Supplementary Material). Screening is not generally recommended for the general public or asymptomatic population. Both earlier and recent guidelines recommend assessment for those at risk of AD, such as adults with intellectual disability [31], patients > 75 years who complain of memory impairment or have a family history of memory disorders [32] and individuals suspected of cognitive impairment by a physician despite a lack of complaint [33]. Biomarker testing was specifically not recommended in four earlier guidelines and two most recent guidelines, indicating a lack of support for its routine use. While two recent MCI guidelines considered offering biomarker testing to clarify the underlying cause of the cognitive impairment, they did not advocate its use for routine diagnosis [20, 30].

We identified two earlier systematic reviews (one that summarizes guidelines for AD diagnostic testing [34] and one for MCI screening, diagnosis and treatment [35]) in our guidelines database searches that are described in the Supplementary Material.

This study, like other SLRs, has strengths and limitations. The main strength was the identification of clinical practice guidelines for geographically diverse countries for early AD including MCI and AD-related dementia using a predefined protocol and a 2-phase screening process independently undertaken by two reviewers. Inclusion and exclusion processes were documented, including completion of a PRISMA flow chart [36]. However, the current study has certain limitations. Although no language restrictions were applied in the systematic searches, the final 53 practice guidelines eligible for data extraction were all published in English, potentially missing relevant recommendations in other languages. Additionally, data were not extracted from expert consensus statements, which may have excluded relevant recommendations. Furthermore, the number of Google Scholar citations may not reflect real-world implementation and usage and AGREE II (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation Instrument) was not reported since it was not used to assess the quality of all the included guidelines (see Table 2). In addition, the strength of the reported recommendations was not reported, although a rationale for the recommendations was reported where available.

The AD Continuum Practice Guidelines: The Way Forward

In recent years, several publications have provided recommendations for the diagnosis and clinical management of preclinical or early-stage AD, following advances in biologic and clinical assessment [6, 11,12,13]. One notable publication from 2022 by Hampel and colleagues [11] emphasized the need for an optimized global framework for biomarker-guided targeted treatments in AD. The authors proposed a blueprint to facilitate the transition from a symptom-led, late-stage diagnosis to a clinical care pathway that includes biomarker-guided and digitally supported algorithms for risk stratification and early and accurate diagnosis. For example, the authors suggest that “blood-based biomarkers reflecting core AD pathology have the potential to serve as triage tools to identify those who should be tested with more resource-demanding techniques” [11]. By allowing treatment in the early stages of the disease, this approach aims to delay or prevent progress to more advanced stages [11].

In 2021, Porsteinsson and colleagues [6] emphasized the importance of early diagnosis of AD and the need for practical guidance and tools to be used throughout the diagnosis. Early AD diagnosis also allows patients to be involved in collaboration with family members and medical professionals in the development of care plans [6]. Dubois and colleagues [12] in 2021 provided recommendations on how biomarkers could be utilized for AD diagnosis in the clinical setting. This international working group recommended that an AD diagnosis should be limited to people with established signs of AD-associated pathophysiology, represented by positive core pathophysiologic biomarkers and specific AD phenotypes (including “atypical” clinical AD presentations). Cummings and colleagues [13] updated an appropriate-use recommendation for aducanumab in 2022. The authors included recommendations to aid in patient selection, improve decision-making and monitor safety and risk mitigation. They highlighted the importance of detecting previous medical conditions that may increase the risk of amyloid-related imaging abnormalities [13].

Recent publications proposing updates to clinical practice for managing the AD continuum have emphasized the importance of early detection. Historically, AD dementia was diagnosed based on the presence of cognitive and behavioral symptoms, with other possible cause excluded, where symptom manifestation is overt and pronounced [37]. The systematic and unbiased identification of pathophysiologic biomarker signatures of AD early in the AD continuum will help optimize the success of DMT candidates designed to prevent or delay clinical onset or progression of AD dementia [37, 38]. Specifically, blood- and plasma-based biomarker assays for amyloid and tau, as well as other emerging pathophysiologic mechanisms, are expected to increase the likelihood of early detection and diagnosis of AD occurring in general neurology and general practitioner settings in the future rather than specialized neurology settings [37]. It is anticipated that, in the future, blood-based biomarkers may be developed for other contexts of use, including predicting risk of disease, monitoring response to treatment and assessing disease progression [37].

A systematic approach is crucial to the evaluation and management of cognitive impairment in patients. This approach encompasses cognitive testing, examination, imaging and laboratory analysis to establish a comprehensive understanding of the patient’s condition. The diagnostic process involves assessing the level of impairment (e.g., mild cognitive impairment or dementia) and identifying the probable cause (e.g., Alzheimer’s disease, dementia with Lewy bodies or vascular dementia). Additionally, it is essential to screen for conditions that can affect cognition, such as hypothyroidism, vitamin B12 deficiency, anemia, kidney or liver failure, and electrolyte imbalances. Addressing these underlying conditions through appropriate treatment holds potential for ameliorating cognitive decline [39].

Although appropriate-use recommendations are now being discussed for DMTs, our review demonstrates that these therapies are not yet included in current guidelines, which typically lag behind research findings by several years. However, once approved, clinicians will require guidance on the appropriate use of DMTs in a clinical setting. This guidance should include strategies for identifying eligible patients and evaluating the DMT benefit-to-risk profile to facilitate shared decision-making among physicians, patients and care partners [40].

The issue of clinical practice guidelines not being aligned with the latest clinical research has been discussed previously in the literature [41, 42]. There may be potential to learn from guidelines developed in other therapy areas. Levine et al. [43] illustrate how a professional society and nonprofit organizations have innovated the clinical practice guideline development process. The American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association Task Force have introduced guideline innovations and modifications since 2017 to achieve the following objectives: (1) make published guidelines more “user friendly;” (2) focus on the actual clinical recommendations rather than extensive text; (3) format the guidelines to support the development of updates; (4) format information that facilitates integration into electronic media [43].

We believe that clinical practice guidelines are essential tools in healthcare that provide evidence-based recommendations for medical professionals. Developed by expert panels or professional organizations, clinical practice guidelines offer comprehensive guidance for the diagnosis, treatment and management of specific medical conditions. They are based on a thorough review of the available evidence, evaluating its quality and synthesizing recommendations based on the strength of evidence.

While consensus statements and appropriate use recommendations focus on specific areas in disease management, clinical practice guidelines offer a comprehensive, evidence-based approach that provides standardized, patient-centered care. They serve as a valuable resource for healthcare professionals, healthcare systems and policymakers, ultimately leading to improved patient outcomes and the advancement of healthcare practices.

Conclusion

Clinical practice recommendations for the AD continuum have remained largely consistent and unchanged across various countries and global regions over the past 2 decades, with no recommendations for screening or biomarker testing for asymptomatic populations and pharmacologic treatment for cognitive symptoms only recommended for those with AD dementia. Regular, evidence-based updates of existing guidelines for the AD continuum are required over the coming decades to integrate rapidly evolving technologic and medical scientific advances and bring emerging approaches for management of early disease into clinical practice. This will pave the way toward biomarker-guided identification and targeted treatment and the realization of precision medicine for AD.

References

National Institues of Health. What are clinical practice guidelines? National Library of Medicine; 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK390308/. Accessed 6 Jan 2023.

Yi TW, Donnellan S, Levin A. Evidence-based decision making 4: clinical practice guidelines. Methods Mol Biol. 2021;2249:455–66.

Dubois B, Feldman HH, Jacova C, et al. Revising the definition of Alzheimer’s disease: a new lexicon. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9(11):1118–27.

Dubois B, Hampel H, Feldman HH, et al. Preclinical Alzheimer’s disease: definition, natural history, and diagnostic criteria. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12(3):292–323.

Cho SH, Woo S, Kim C, et al. Disease progression modelling from preclinical Alzheimer’s disease (AD) to AD dementia. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):4168.

Porsteinsson AP, Isaacson RS, Knox S, Sabbagh MN, Rubino I. Diagnosis of early Alzheimer’s disease: clinical practice in 2021. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2021;8(3):371–86.

Hampel H, Mesulam MM, Cuello AC, et al. The cholinergic system in the pathophysiology and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2018;141(7):1917–33.

Hampel H, Hardy J, Blennow K, et al. The amyloid-beta pathway in Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Psychiatry. 2021;26(10):5481–503.

Cummings J, Lee G, Nahed P, et al. Alzheimer’s disease drug development pipeline: 2022. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2022;8(1): e12295.

Cummings J, Fox N. Defining disease modifying therapy for Alzheimer’s disease. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2017;4(2):109–15.

Hampel H, Au R, Mattke S, et al. Designing the next-generation clinical care pathway for Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Aging. 2022;2(8):692–703.

Dubois B, Villain N, Frisoni GB, et al. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations of the International Working Group. Lancet Neurol. 2021;20(6):484–96.

Cummings J, Rabinovici GD, Atri A, et al. Aducanumab: appropriate use recommendations update. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2022;9(2):221–30.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;21;6(7):e1000097.

Jack CR Jr, Bennett DA, Blennow K, et al. NIA-AA research framework: toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14(4):535–62.

Guedj E, Varrone A, Boellaard R, et al. EANM procedure guidelines for brain PET imaging using [18F]FDG, version 3. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2022;49(2):632–51.

Huang LK, Chiu PY, Yeh YC, et al. Taiwan Dementia treatment guideline. Int J Gerontol. 2021;15(4):292–300.

International clinical practice guideline of Chinese Medicine Alzheimer. World J Tradit Chin Med. 2021;7(2):265–75.

Reeve E, Farrell B, Thompson W, et al. Deprescribing cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine in dementia: guideline summary. Med J Aust. 2019;210(4):174–9.

Petersen RC, Lopez O, Armstrong MJ, et al. Practice guideline update summary: mild cognitive impairment report of the guideline development, dissemination, and implementation. Neurology. 2018;90(3):126–35.

Shaji KS, Sivakumar PT, Rao GP, Paul N. Clinical practice guidelines for management of dementia. Indian J Psychiatry. 2018;60(Suppl 3):S312–28.

Lee JS, Kim GH, Kim HJ, et al. Clinical practice guideline for dementia (diagnosis and evaluation): 2021 revised edition. Dement Neurocogn Disord. 2022;21(1):42–4.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Dementia: assessment, management and support for people living with dementia and their carers. 2018. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng97/resources/dementia-assessment-management-and-support-for-people-living-with-dementia-and-their-carers-pdf-1837760199109.

Reeve E, Farrell B, Thompson W, et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guideline for deprescribing cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine in people with dementia. Recommendations The University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia. 2018.

Danish Health Authority. National clinical guideline on dementia and medicine. 2018. https://www.sst.dk/-/media/Udgivelser/2018/NKR-medicin-og-demens/EN/Quick-Guide-NKR-demens-og-medicin_EN.ashx. Accessed 16 June 2022.

Department of Health Dublin. Appropriate prescribing of psychotropic medication for non-cognitive symptoms in people with dementia. National clinical guideline no. 21; 2019. https://www.gov.ie/en/collection/ac0046-appropriate-prescribing-of-psychotropic-medication-for-non-cognitive/. Accessed 17 June 2022.

Ministry of Health Malaysia. Clinical practice guidelines: management of dementia. 2021.

Foley T, Jennings A, Swanwick G. Dementia: diagnosis & management in general practice: ICGP Quality and Safety in Practice Committee. 2019.

World Health Organization. Risk reduction of cognitive decline and dementia: WHO guidelines. January 1, 2019. 2022. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241550543. Accessed 17 June.

Danish Health Authority. National clinical guideline for diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment and dementia. 2018. https://www.sundhedsstyrelsen.dk/-/media/Udgivelser/2018/NKR-Diagnostik-af-mild-cognitive-impairment-og-demens/Quick-guide---National-Clinical-Guideline-for-Diafnosis-of-Mild-Cognitive-Impairment-and-Dementia.ashx?sc_lang=da&hash=AEAEFA87F77D7D3E2C49400F2ED7A228. Accessed 16 June 2022.

Janicki MP, Heller T, Seltzer GB, Hogg J. Practice guidelines for the clinical assessment and care management of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias among adults with intellectual disability. J Intellect Disabil Res. 1996;40(4):374–82.

Fillit H, Cummings J. Disease management. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of Alzheimer's disease in a managed care setting: part I—early detection and diagnosis...in part II, and the conclusion of this article, which will appear next month, the authors describe the pharmacologic treatment guidelines designed by the Alzheimer's Disease Managed Care Advisory Council. Managed Care Interface. 1999;12(12):53–62.

Ministry of Health Singapore. Dementia. 2013. https://www.moh.gov.sg/docs/librariesprovider4/guidelines/dementia-10-jul-2013---booklet.pdf. Accessed 16 June 2022.

Arevalo-Rodriguez I, Pedraza OL, Rodríguez A, et al. Alzheimer’s disease dementia guidelines for diagnostic testing: a systematic review. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2013;28(2):111–9.

Chen YX, Liang N, Li XL, Yang SH, Wang YP, Shi NN. Diagnosis and treatment for mild cognitive impairment: a systematic review of clinical practice guidelines and consensus statements. Front Neurol. 2021;12: 719849.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;29(372): n71.

Hampel H, Cummings J, Blennow K, Gao P, Jack CR Jr, Vergallo A. Developing the ATX(N) classification for use across the Alzheimer disease continuum. Nat Rev Neurol. 2021;17(9):580–9.

Baldacci F, Mazzucchi S, Della Vecchia A, et al. The path to biomarker-based diagnostic criteria for the spectrum of neurodegenerative diseases. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2020;20(4):421–41.

McCollum L, Karlawish J. Cognitive impairment evaluation and management. Med Clin N Am. 2020;104(5):807–25.

Cummings J, Aisen P, Apostolova LG, Atri A, Salloway S, Weiner M. Aducanumab: appropriate use recommendations. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2021;8(4):398–410.

Shekelle P, Woolf S, Grimshaw JM, Schunemann HJ, Eccles MP. Developing clinical practice guidelines: reviewing, reporting, and publishing guidelines; updating guidelines; and the emerging issues of enhancing guideline implementability and accounting for comorbid conditions in guideline development. Implement Sci. 2012;4(7):62.

Becker M, Neugebauer EA, Eikermann M. Partial updating of clinical practice guidelines often makes more sense than full updating: a systematic review on methods and the development of an updating procedure. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(1):33–45.

Levine GN, O’Gara PT, Beckman JA, et al. Recent innovations, modifications, and evolution of ACC/AHA clinical practice guidelines: an update for our constituencies: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2019;139(17):e879–86.

Ingravallo F, Dietrich C, Gilja O, Piscaglia F. Guidelines, clinical practice recommendations, position papers and consensus statements: definition, preparation, role and application. Ultraschall Med. 2014;35(05):395–9.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This research was supported by Eisai Inc. RTI Health Solutions, an independent nonprofit research organization, received funding under a research contract with Eisai Inc. to conduct this study and provide publication support in the form of manuscript writing, styling and submission. NT Nhan Phan, Isobel Pearson and Josephine Mauskopf are employees of RTI Health Solutions, an independent nonprofit research organization, which received funding pursuant to a contract with Eisai Inc.

Medical Writing and/or Editorial Assistance

John Forbes and Jonathan Pattishall of RTI Health Solutions provided editorial services during development of this manuscript. These services were funded by Eisai Inc.

Author Contributions

All authors—Amir Abbas Tahami Monfared, NT Nhan Phan, Isobel Pearson, Josephine Mauskopf, Min Cho, Quanwu Zhang and Harald Hampel—made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; and agree to be accountable for the work.

Disclosures

Amir Abbas Tahami Monfared is an employee of Eisai Inc. He serves as Associate Editor for the Journal of Alzheimer's Disease and did not receive any fees or honoraria. Min Cho is an employee of Eisai Inc. Quanwu Zhang is an employee of Eisai Inc. Josephine Mauskopf, Isobel Pearson and NT Nhan Phan are employees of RTI Health Solutions that received funding from Eisai Inc to perform the study. Harald Hampel is an employee of Eisai Inc. He serves as Senior Associate Editor for the Journal Alzheimer's & Dementia and did not receive any fees or honoraria since May 2019. He is inventor of 11 patents and has received no royalties: In Vitro Multiparameter Determination Method for The Diagnosis and Early Diagnosis of Neurodegenerative Disorders Patent Number: 8916388; In Vitro Procedure for Diagnosis and Early Diagnosis of Neurodegenerative Diseases Patent Number: 8298784; Neurodegenerative Markers for Psychiatric Conditions Publication Number: 20120196300; In Vitro Multiparameter Determination Method for The Diagnosis and Early Diagnosis of Neurodegenerative Disorders Publication Number: 20100062463; In Vitro Method for The Diagnosis and Early Diagnosis of Neurodegenerative Disorders Publication Number: 20100035286; In Vitro Procedure for Diagnosis and Early Diagnosis of Neurodegenerative Diseases Publication Number: 20090263822; In Vitro Method for The Diagnosis of Neurodegenerative Diseases Patent Number: 7547553; CSF Diagnostic in Vitro Method for Diagnosis of Dementias and Neuroinflammatory Diseases Publication Number: 20080206797; In Vitro Method for The Diagnosis of Neurodegenerative Diseases Publication Number: 20080199966; Neurodegenerative Markers for Psychiatric Conditions Publication Number: 20080131921; Method for diagnosis of dementias and neuroinflammatory diseases based on an increased level of procalcitonin in cerebrospinal fluid: Publication number: United States Patent 10921330.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article/as supplementary information files.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tahami Monfared, A.A., Phan, N.T.N., Pearson, I. et al. A Systematic Review of Clinical Practice Guidelines for Alzheimer’s Disease and Strategies for Future Advancements. Neurol Ther 12, 1257–1284 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-023-00504-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-023-00504-6