Abstract

Background

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) pathology begins several years before the clinical onset. The long preclinical phase is composed of three stages according to the 2011National Institute on Aging and Alzheimer’s Association (NIA-AA) criteria, followed by mild cognitive impairment (MCI), a featured clinical entity defined as “due to AD”, or “prodromal AD”, when pathophysiological biomarkers (i.e., cerebrospinal fluid or positron emission tomography with amyloid tracer) are positive. In the clinical setting, there is a clear need to detect the earliest symptoms not yet fulfilling MCI criteria, in order to proceed to biomarker assessment for diagnostic definition, thus offering treatment with disease-modifying drugs to patients as early as possible. According to the available evidence, we thus estimated the prevalence and risk of progression at each preclinical AD stage, with special interest in Stage 3.

Methods

Cross-sectional and longitudinal studies published from April 2008 to May 2018 were obtained through MEDLINE-PubMed, screened, and systematically reviewed by four independent reviewers. Data from included studies were meta-analyzed using random-effects models. Heterogeneity was assessed by I2 statistics.

Results

Estimated overall prevalence of preclinical AD was 22% (95% CI = 18–26%). Rate of biomarker positivity overlapped in cognitively normal individuals and people with subjective cognitive decline. The risk of progression increases across preclinical AD stages, with individuals classified as NIA-AA Stage 3 showing the highest risk (73%, 95% CI = 40–92%) compared to those in Stage 2 (38%, 95% CI = 21–59%) and Stage 1 (20%, 95% CI = 10–34%).

Conclusion

Available data consistently show that risk of progression increases across the preclinical AD stages, where Stage 3 shows a risk of progression comparable to MCI due to AD. Accordingly, an effort should be made to also operationalize the diagnostic work-up in subjects with subtle cognitive deficits not yet fulfilling MCI criteria. The possibility to define, in the clinical routine, a patient as “pre-MCI due to AD” could offer these subjects the opportunity to use disease-modifying drugs at best.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive disorder with a long-lasting asymptomatic phase followed by a symptomatic predementia phase, and finally by the dementia stage [1, 2].

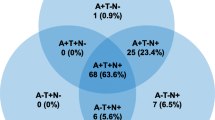

Based on the dynamical model driven by the amyloid cascade, the pathophysiological AD processes begin several years before the onset of clinical symptoms [1]. These pathophysiological processes taking place in the brain are reliably detectable in vivo by cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) or imaging biomarkers, which are needed for diagnosing AD in the predementia phase [1, 3,4,5,6,7]. In recent years, the linear model in which a mechanical sequence occurs—starting from amyloidosis and then leading to neuronal injury—has been questioned, since cases of neurodegeneration preceding incipient brain amyloid pathology have been described [8,9,10,11,12]. The research framework for preclinical AD [13, 14] recently proposed a descriptive system, based on a categorical classification of biomarker positivity (A/T/N): “A” refers to amyloid pathology, assessed by either Aβ42 or the Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio in CSF or amyloid PET; “T” refers to tau pathology, assessed by CSF phospho-tau or PET with tau tracer; and “N” refers to neurodegeneration, assessed by CSF total tau, MRI, or FDG-PET. This classification model represents an advancement from the 2011 NIA-AA [2, 6] and IWG-2 [4, 5] criteria, since it takes into account several pathophysiological profiles underlying different conditions. All of them may lead to different trajectories, identifying specific prognostic features and cognitive outcomes. In this model, the only presence of brain amyloidosis identifies “AD pathologic change” [14]. Conversely, an early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease requires the presence of both amyloidosis (A+) and tauopathy (T+), where the positivity of an injury biomarker (N) is not mandatory for diagnostic purposes since it represents an unspecific measure of neuronal damage entity. Currently, an attempt has been proposed to compare the NIA-AA preclinical AD stages [2] and the A/T/N classification in cognitively normal individuals proposed in the 2018 NIA-AA Research Framework [15]. Accordingly, NIA-AA Stage 3 seems to correspond to Stage 2 in the 2018 NIA-AA Research Framework.

Pathophysiological AD biomarker positivity represents a mandatory criterion for inclusion in clinical trials with novel therapeutic drugs [4]. Up to now, in clinical terms, the only well-defined symptomatic predementia stage in routine diagnostic work-up is represented by mild cognitive impairment (MCI), a clinical entity in which cognitive deficits do not fulfill dementia criteria [6, 16, 17]. In the last years, an increasing number of papers have been focused on the phase preceding MCI (i.e., “pre-MCI phase”) [18, 19]. Although no shared definition is available, several attempts have been carried out to characterize the symptomatic debut of AD.

In the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiatives (ADNI, ADNI GO, and ADNI 2), the MCI stage was divided into early MCI (EMCI) and late MCI (LMCI) [20,21,22]. Both of these are characterized by evidence of AD biomarker abnormalities, where EMCI patients show milder cognitive deficits. In terms of neuropsychological criteria, EMCI is defined as a performance 1–1.5 SD below the mean in one episodic memory test, identifying subtle memory impairment at an intermediate level between normal cognition and MCI [20, 23]. However, this definition remains controversial.

Based on the 2011 National Institute on Aging and Alzheimer’s Association (NIA-AA) staging of preclinical AD [2], cognitive decline emerges in the last step of the preclinical continuum (i.e., Stage 3) as “subtle cognitive decline”. However, how this decline could be quantified is not well defined, and a consensus on cognitive measures reliably depicting such subtle deficits is not yet available. Epelbaum et al. [24] suggest an entity named “Preclinical AD with subtle cognitive changes” (attention impairment or dysexecutive symptoms) displaying performances less than 1 SD below the age-corrected normative mean in one or more cognitive measure. The concept of what represents a “subtle” decline is challenging also due to recent evidence that subtle signs of cognitive dysfunction may precede Aβ-positivity several years before the threshold for pathological Aβ accumulation is reached [25].

A more extensive neuropsychological evaluation can help in detecting cognitive alterations in pre-MCI phases of AD [2, 11, 26, 27]. Among neuropsychological measures, composite scores (obtained by normalizing and summing up standardized z scores) have proved to have higher sensitivity than single scores at cognitive tests in detecting changes over time within the preclinical AD stages [27,28,29,30,31,32,33]. Accordingly, they have also been introduced as outcome measures in prevention trials [5, 31, 32, 34].

A feature that can accompany the symptomatic debut of AD is the presence of subjective cognitive concerns. Self-reported experiences of cognitive decline have been defined using different labels—subjective cognitive impairment (SCI) [35], subjective cognitive complaints (SCC) [36], subjective memory impairment (SMI) [37], and subjective memory complaints (SMC) [38]—leading to a highly heterogeneous lexicon. In 2014, the Subjective Cognitive Decline Initiative (SCD-I) working group tried to reduce this complexity by reaching a consensus on terminology, using the definition of subjective cognitive decline (SCD), recently operationalized [39]. SCD refers to a self-experienced decline in some cognitive abilities in comparison with a previous normal status, in spite of normal performance on standardized cognitive tests.

Whether this condition may or may not represent an increased risk for progression to MCI and/or dementia is still a controversial issue [40]. However, a consistent body of evidence indicates that SCD actually represents a risk factor for future cognitive decline, for MCI and AD dementia [30, 40,41,42,43,44,45], particularly when worries are reported [46,47,48]. Dubois et al. [5, 49] specify that the SCD per se cannot be considered as a “proxy” for preclinical AD, in line with studies reporting that the percentage of amyloid PET positivity is independent from rates of memory complaints [50, 51]. However, SCD individuals with evidence of pathophysiological AD biomarker positivity (SCD plus) represent a category at risk for clinical AD [39].

According to available papers published between 2008 and 2018, our systematic review aimed to estimate the prevalence of AD pathophysiological biomarker positivity (CSF, amyloid PET) across all individuals lying in the spectrum preceding MCI, including subjects defined as cognitively normal (CN) or in subjective cognitive decline. In these categories, we then calculated the risk of clinical progression to MCI and/or dementia.

Methods

Our systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted according to the PRISMA guidelines (see Additional file 1: Table S1) [52].

Data sources and search strategy

We searched MEDLINE (via PubMed) from April 2008 to May 2018. We examined reference lists of all eligible studies and reviews in the field for further possible titles; the process was repeated until no new titles were found.

For the search strategy we used the following terms: “preclinical” OR “asymptomatic” OR “pre-MCI” OR “preMCI” OR “pre MCI” OR “cognitively normal” OR “normal aging” OR “subjective memory complaint*” OR “subjective memory impairment” OR “subjective cognitive complaint*” OR “subjective cognitive impairment” OR “subjective cognitive decline” OR “memory complaint*” OR “cognitive complaint*” OR “subjective cognitive” OR “subjective memory” OR “SCD” OR “subtle cognitive decline” OR “early diagnosis” OR “Stage” AND “Alzheimer*” AND “biomarker” OR “abeta” OR “amyloid-beta” OR “amyloid” OR “tau” OR “t-tau” OR “p-tau” OR “total tau” OR “phospho-tau” OR “phosphorylated tau” OR “hyperphosphorylated tau” OR “PET” OR “positron emission tomography” OR “CSF” OR “cerebrospinal fluid” OR “amyloid PET”.

Data extraction

Four investigators (EC, NS, PE, and KDA) conducted literature searches and extracted data ensuring two independent evaluations for each record. Disagreements were resolved by means of consensus.

Inclusion criteria

We limited the search to the previous 10 years, referring to articles following the publication of the IWG criteria and revision of the NINCS-ADRDA by Dubois et al. [53] where the assessment of in-vivo AD biomarkers was considered a fundamental step, supportive to the clinical phenotype, in improving the accuracy of early AD diagnosis. Studies were included if pathophysiological biomarkers (CSF amyloid-β1–42, t-tau, and p-tau, or Aβ42/tau ratio, or amyloid PET including any amyloid tracer and assessment via visual scales or quantitative measures) for defining preclinical AD were used and if CSF biomarkers and amyloid PET resulted negative or positive according to study-specific cutoff points. We have considered prospective and retrospective cohort studies that included one of the following three categories of pre-MCI individuals: cognitively normal (CN), as defined by normal scores on cognitive tests; subjective cognitive decline, as defined by the presence of cognitive complaints associated with normal performance in cognitive tests (we included studies that classified subjects as subjective cognitive decline (SCD), subjective memory complaints (SMC), subjective memory impairment (SMI), subjective cognitive complaints (SCC), and subjective cognitive impairment (SCI), and included people with reported SCD at baseline assessed with any kind of method (e.g., single dichotomous questions, questionnaires, interviews)); and Stage 3 of preclinical AD continuum, as defined in the 2011 NIA-AA criteria [2] by presence of amyloidosis, neurodegeneration, plus subtle cognitive decline (any cognitive decline or impairment in any neuropsychological assessment which does not reach MCI criteria). Studies with fewer than 50 subjects in our groups of interest were excluded. A sample size of 50 was chosen in order to increase the probability of including studies at low/moderate risk of bias. When more than one study reported results of a specific cohort (i.e., ADNI cohort), we included the one with the largest sample size.

Operationalization criteria for evaluating the risk of progression

In studies reporting longitudinal follow-up we have considered as clinical progression the onset of MCI, progression from normal cognition to MCI or dementia, change in CDR score, cognitive decline in neuropsychological tests, or any of these conditions.

Risk of bias assessment

The methodological quality of the included studies was evaluated with the tool developed by Hoy et al. [54]. A score of 1 (yes) or 0 (no) was assigned for each item, and scores were summed across items to generate an overall quality score that ranged from 0 to 10. Studies were then classified as having a low (> 8), moderate [6,7,8], or high (≤ 5) risk of bias. Two investigators independently assessed the study’s methodological quality (EC, NS), with disagreements resolved by a third investigator (PE).

Data analysis

Data analysis was performed using R software version 3.4, and the meta package was used for meta-analysis [55]. For each study we summarized several characteristics of the participants such as gender, age, years of education, and ethnicity. Prevalence and relative risks (RR) were meta-analyzed using random-effects models. Summary estimates were provided along with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). Heterogeneity among studies was assessed using I2 statistics. When considering the prevalence of preclinical AD, we explored several study-level characteristics as sources of heterogeneity by means of meta-regression models and subgroup analyses. In the meta-analysis of relative risk of progression, publication bias was assessed by means of funnel plot. P < 0.05 was considered significant in all of the analyses.

Results

Characteristics of included studies

We identified 2792 articles from the PubMed screen. Four-hundred and thirty-six full-text articles were assessed for eligibility, and 36 articles were included in the systematic review and meta-analyses (Fig. 1). These reports were representative of 6602 subjects with mean age ranging from 53 to 86 years. Thirty-three papers assessed preclinical AD in cognitively normal subjects, reporting data on 5537 subjects. Other papers assessed SCD (three studies, 280 subjects), SCI (one study, 60 subjects), and SMC (three studies, 725 subjects).

Amyloid-PET data were extracted from 20 studies. Of these, 14 studies used [11C]Pittsburgh compound-B (PiB) radiotracer, three used [18F]florbetapir, and three used [18F]florbetaben. CSF data were available in 15 studies. Of these, an AD-like profile (i.e., abnormal Aβ42, total tau, and p-tau) was reported in 14 studies and altered CSF Aβ42/t-Tau ratio in one study (see Additional file 2: Table S2).

Neuropsychological criteria for the definition of diagnostic groups were heterogeneous. Baseline characteristics according to cognitive criteria were CDR = 0 (12 studies, 3484 subjects), CDR = 0 plus Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) score ≥ 27 (five studies, 1086 subjects), no neuropsychological deficits and not reaching MCI criteria (13 studies, 3297 subjects), score ≥ 23 on Montreal Cognitive Assessment (one study, 132 subjects), and cutoff value 1SD below the age-corrected normative mean in the neuropsychological battery (one study, 570 subjects).

Baseline criteria to define SCD were presence of self-report cognitive complaints (five studies, 765 subjects) and SCD-I criteria [39] (one study, 85 subjects). Only in one study [56] was SCD assessed by means of specific questionnaires (318 subjects). Baseline criteria to define subtle cognitive decline were applied only in four studies and were heterogeneous: > 1 SD below the age-corrected normative mean on two of six neuropsychological measures in different cognitive domains, Functional Assessment Questionnaire score ≥ 6 (one study, 50 subjects); − 1.25 SD at MMSE and one episodic memory composite score (one study, 13 subjects); lowest 10th percentile in a global cognitive summary score (one study, six subjects); and 1.5 SD less than mean score in one neuropsychological test obtained in normal controls (one study, six subjects).

Years of education (see Additional file 2: Table S3) and gender were included as covariates in meta-regression but they turned out to be not significantly associated with preclinical AD prevalence. Age was consistently associated with preclinical AD according to meta-regression results but this was not sufficient to explain heterogeneity. In fact, heterogeneity continued to remain substantial even when subgroup analyses were carried out according to the mean age of participants (see Additional file 3: Figure S1).

The characteristics of the studies included in the systematic review and meta-analysis are reported in Table 1. Since only two studies provided data on ethnicity, we have not included these data within the demographics. This, however, highlights the need for large studies paying attention to the inclusion of different ethnicities, in order to obtain results that may be generalized to the whole population.

After evaluating the risk of bias, we judged that 14 studies were at low risk of bias, 21 at moderate risk, and none at high risk. According to the risk of bias assessment, we found that in most of the included studies this was based on enrollment procedures that do not ensure a true or close representation of the target population (n = 26). In many cases, the study’s population was not representative of the national population (n = 25) and almost all of the studies were conducted without random sampling or census. Detailed results are reported in Additional file 4: Table S4).

We first considered evidence of abnormalities in the AD diagnostic markers (CSF AD profile, either with the three biomarkers altered [amyloid-β1–42 plus t-tau and p-tau] or Aβ42/tau ratio, or amyloid PET positivity) in cognitively healthy subjects, so defined as preclinical AD (Fig. 2). Preclinical AD was documented in 22% of cognitively normal individuals (95% CI = 18–26%, I2 = 92%). Prevalence was dependent on age, as tested with meta-regression, ranging from 16.5% at 53 years to 53% at 86 years [57], with an increase in prevalence of 1.0% per year (95% CI = 0.5–5%). According to CSF analysis, preclinical AD was found in 21% of individuals (95% CI = 15–29%, I2 = 94%), as compared to 22% (95% CI = 18–27%, I2 = 90%) when considering amyloid-PET positivity.

Prevalence of preclinical AD in individuals with subjective cognitive decline was analogous to that documented in normal subjects (23%, 95% CI = 14–33%, I2 = 92%), ranging from 7% [58] to 52% [59].

Prevalence of preclinical AD stages according to 2011 NIA-AA criteria

We calculated the prevalence of preclinical AD stages, defined according to 2011 NIA-AA criteria, in six studies published after 2011, between 2011 and 2018 (Fig. 3). Prevalence of Stage 1 was 13% (95% CI = 9–18%, I2 = 81%), of Stage 2 was 16% (95% CI = 9–25%, I2 = 94%), and of Stage 3 was 5% (95% CI = 3–9%, I2 = 80%).

Clinical progression

Positivity of biomarkers confers a higher relative risk of clinical progression as measured by conversion to MCI or AD (RR = 2.75, 95% CI = 2.32–3.27, I2 = 67%). The risk of clinical progression is analogous in cognitively normal subjects (RR = 2.65, 95% CI = 2.18–3.23, I2 = 53%) and in subjects with SCD, SCI, or SMC (RR = 3.30, 95% CI = 2.41–4.53, I2 = 87%). Rates of clinical progression across the 2011 NIA-AA preclinical AD stages are presented in Table 2. The risk of progression increases across preclinical AD stages, with individuals classified as NIA-AA Stage 3 showing the highest risk (73%, 95% CI = 40–92%) compared to those in Stage 2 (38%, 95% CI = 21–59%) and Stage 1 (20%, 95% CI = 10–34%). The clinical progression rate in Stage 3 was significantly higher as compared to subjects classified as having normal biomarkers (RR = 6.38, 95% CI = 3.33–12.24, I2 = 73%; Fig. 4), in Stage 1 (RR = 3.23, 95% CI = 1.96–5.34, I2 = 45%), and in Stage 2 (RR = 1.86, 95% CI = 1.04–3.33, I2 = 90%).

Discussion

The primary aim of this systematic review was to evaluate whether preclinical AD Stage 3 might rather be considered the clinical debut of AD. This conceptual change would imply that in clinical practice we should actively look for it as a specific clinical entity. To do this, all of the existing data from studies assessing the prevalence of AD pathophysiological biomarker positivity (CSF, amyloid PET) in the whole spectrum preceding MCI (cognitively normal subjects, subjective cognitive decline, subtle impairment not fulfilling MCI criteria, n = 6602), as well as their evolution toward cognitive worsening/dementia, were analyzed. In the cohorts examined, along the preclinical AD phases, mean prevalence of Stage 3 is 5%, similar to what was found in the ADNI cohort, in which the prevalence of Stage 3 ranges from 2% up to 9% [11]. In this stage, according to available data (different cohorts followed up for 1–4 years), the pooled risk of progression was 73% (95% CI = 40–92%); that is, individuals show, on average, a 6-fold increased risk of progression (relative risk ranging from 3.4 to 34.7; Fig. 4) compared to those with normal biomarkers (Stage 0). These figures are quite similar to those observed for MCI due to AD, which shows a 3-year progression rate to dementia of around 60%, with a hazard ratio of 14 (95% CI = 5.9–35.2) [60]. Overall positivity of pathophysiological biomarkers was similar between amyloid PET (22%) and CSF (25%). Differences in rates of positivity in CSF vs amyloid PET in CN range from 8 to 21% [61,62,63,64]. CN and SCD groups do not differ in rates of biomarker positivity, possibly due to the unclear differentiation between these categories.

An AD-like CSF profile, as well as a positive amyloid PET, is not rarely observed in cognitively normal individuals [65], and such positivity increases with age [65,66,67]. No longitudinal data assessing these subjects for an extended time window (> 10 years) are available, therefore we cannot take into account the actual value of these data as a matter of preclinical AD.

An important issue in our systematic review concerns the different methods applied for cognitive characterization of CN individuals, and this could explain the heterogeneity in prevalence of pathophysiological biomarker positivity and risk of progression. Some studies used a CDR score of 0 [12, 68], other studies report the MMSE scores [69, 70], and other investigations refer to a condition not fulfilling MCI criteria, without any specific definition [71]. In the clinical setting, subtle, although detectable, cognitive decline in a subject who expresses the will to learn about the cause of her/his impairment may justify biomarker assessment. At present, neuropsychological criteria defining “subtle” cognitive decline are not yet available [11, 63]. According to Epelbaum et al. [24], different cutoff scores might be used, namely a performance below 1.5 SD in two out of six cognitive measures [72], or below 1 SD in one neuropsychological test [11, 24], or performances falling below the 10th percentile [8, 73]. The MMSE is not appropriate for detecting subtle symptoms. Therefore, more sensitive cognitive measures should be used, namely composite scores, which are also able to track subtle decline over time. Since subtle cognitive decline has been considered either as cognitive changes over time, in longitudinal cohorts, or poorer scores at baseline, in cross-sectional studies [12], it is necessary to further address this issue in ad-hoc studies. These data confirm how difficult it is to define the boundary between normal cognition and subtle cognitive deficits, and measurement of the change with time might be the right option, in terms of prevention/early diagnosis programs.

The lack of consensus about definition of CN individuals may lead to different preclinical AD rates. Accordingly, cognitively normal individuals in the cohorts we examined could have been included either as volunteers—classified as healthy controls in research studies—or considered as a control group in post-hoc analysis, when cross-sectional studies were included (i.e., ADNI cohorts). These two different criteria for subject selection may actually reflect two distinct populations. Such a difference can lead to noncomparable findings.

Importantly, the analyses indicated a great heterogeneity in SCD definition. Up to now, although an attempt to implement SCD research criteria toward a harmonization of SCD measures has been recently carried out [46], no common criteria are available [33, 43, 56, 74]. Only one study followed SCD-I [39, 58], another investigation considered the presence of complaints about memory [75], and only one investigation used a specific questionnaire to objectify the complaints [56]. A possible explanation could be the wide time window (2008–2018) we considered for paper selection, reflecting the lexical evolution of SCD as an entity, according to SCD-I criteria [39]. Recent work by Opdebeeck et al. [76] found that different methods to assess SCD may lead to different conclusions about the rates of risk progression explaining discrepancies in the predictive value of SCD among studies. Therefore, longitudinal studies about SCD are needed to understand the role and predictive value of this entity. According to Sperling et al. [2], SCD is not a mandatory step along the preclinical AD stages [72].

With respect to the diagnostic equivalence of pathophysiological biomarkers, consistent evidence shows that CSF biomarkers and amyloid PET are comparable in detecting the AD signature [61]. CSF biomarkers have the advantage to give simultaneous information about the presence of amyloidosis (Aβ42, Aβ42/40), tauopathy (p-tau), and neurodegeneration (total tau). According to the recent NIA-AA Research Framework [14], in order to diagnose AD, the positivity of both markers of brain amyloidosis (A+) and markers of tauopathy (T+) is needed, regardless of the clinical stage.

Conclusions

According to the available data in terms of prevalence and risk of progression of 2011 NIA-AA preclinical AD Stage 3, subtle cognitive decline associated with pathophysiological AD biomarker positivity likely represents the earliest symptomatic phase of AD, thus belonging to clinical, rather than preclinical, AD ("pre-MCI due to AD"). Accordingly, individuals belonging to 2011 NIA-AA Stage 3 (i.e., showing subtle cognitive decline and positivity to pathophysiological markers of AD) should be considered in the same way as the category MCI due to AD. This allocation to the clinical phase of AD would allow the clinician to timely include the patient in secondary/tertiary prevention treatment. Before adoption of "pre-MCI due to AD" in routine clinical use, this diagnostic entity deserves to be fully validated with pathological studies as well as with ad-hoc prospective longitudinal observations.

References

Jack CR, Knopman DS, Jagust WJ, Shaw LM, Aisen PS, Weiner MW, et al. Hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers of the Alzheimer’s pathological cascade. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9(1):119–28.

Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, Bennett DA, Craft S, Fagan AM, et al. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):280-92.

Dubois B, Feldman HH, Jacova C, Cummings JL, DeKosky ST, Barberger-Gateau P, et al. Revising the definition of Alzheimer’s disease: a new lexicon. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9(11):1118–27.

Dubois B, Feldman HH, Jacova C, Hampel H, Molinuevo JL, Blennow K, et al. Advancing research diagnostic criteria for Alzheimer’s disease: the IWG-2 criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13(6):614–29.

Dubois B, Hampel H, Feldman HH, Scheltens P, Aisen P, Andrieu S, et al. Preclinical Alzheimer’s disease: definition, natural history, and diagnostic criteria. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12(3):292-323.

Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, Dubois B, Feldman HH, Fox NC, et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):270–9.

Albert M, Zhu Y, Moghekar A, Mori S, Miller MI, Soldan A, et al. Predicting progression from normal cognition to mild cognitive impairment for individuals at 5 years. Brain. 2018;141(3):877–87.

Clifford RJJ, Knopman DS, Jagust WJ, Petersen RC, Weiner MW, Aisen PS, et al. Update on hypothetical model of Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(2):207–16.

Knopman DS, Jack CR, Wiste HJ, Weigand SD, Vemuri P, Lowe VJ, et al. Selective worsening of brain injury biomarker abnormalities in cognitively normal elderly persons with β-amyloidosis. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70(8):1030–8.

Chételat G. Alzheimer disease: Aβ-independent processes-rethinking preclinical AD. Nat Rev Neurol. 2013;9(3):123–4.

Edmonds EC, Delano-Wood L, Galasko DR, Salmon DP, Bondi MW. Subtle cognitive decline and biomarker staging in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;47(1):231–42.

Jack CR Jr, Knopman DS, Weigand SD, Wiste HJ, Vemuri P, Lowe V, et al. An operational approach to NIA-AA criteria for preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol. 2013;71(6):765–75.

Jack CR, Hampel HJ, Universities S, Cu M, Petersen RC. A new classification system for AD, independent of cognition A / T / N: an unbiased descriptive classification scheme for Alzheimer disease biomarkers. Neurology. 2016;0:1–10.

Jack CR, Bennett DA, Blennow K, Carrillo MC, Dunn B, Haeberlein SB, et al. NIA-AA Research Framework: toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14(4):535–62.

Kern S, Zetterberg H, Kern J, Zettergren A, Waern M, Höglund K, et al. Prevalence of preclinical Alzheimer disease: Comparison of current classification systems. Neurology. 2018;90(19):e1682-91.

Petersen RC. Mild cognitive impairment as a clinical entity and treatment target. Arch Neurol. 2004;62(7):1160–3 discussion 1167.

Winblad B, Palmer K, Kivipelto M, Jelic V, Fratiglioni L, Wahlund L-O, et al. Mild cognitive impairment—beyond controversies, towards a consensus: report of the International Working Group on Mild Cognitive Impairment. J Intern Med. 2004;256(3):240–6.

Storandt M, Grant EA, Miller JP, Morris JC. Longitudinal course and neuropathologic outcomes in original vs revised MCI and in pre-MCI. Neurology. 2006;67(3):467–73.

Duara R, Loewenstein DA, Greig MT, Potter E, Barker W, Raj A, et al. Pre-MCI and MCI: neuropsychological, clinical, and imaging features and progression rates. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;19(11):951–60.

Landau SM, Mintun MA, Joshi AD, Koeppe RA, Petersen RC, Aisen PS, et al. Amyloid deposition, hypometabolism, and longitudinal cognitive decline. Ann Neurol. 2012;72(4):578–86.

Wu L, Rowley J, Mohades S, Leuzy A, Dauar MT, Shin M, et al. Dissociation between brain amyloid deposition and metabolism in early mild cognitive impairment. PLoS One. 2012;7(10):e47905.

Qiu Y, Li L, Zhou T, Lu W. Alzheimer’s disease progression model based on integrated biomarkers and clinical measures. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2014;35(9):1111–20.

Risacher SL, Kim S, Nho K, Shen L, Petersen RC, Jr CRJ, et al. APOE effect on Alzheimer's disease biomarkers in older adults with significant memory concern. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2015;11(12):1417-29.

Epelbaum S, Genthon R, Cavedo E, Habert MO, Lamari F, Gagliardi G, et al. Preclinical Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review of the cohorts underlying the concept. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13(4):454–67.

Insel PS, Ossenkoppele R, Gessert D, Jagust W, Landau S, Hansson O, et al. Time to amyloid positivity and preclinical changes in brain metabolism, atrophy, and cognition: evidence for emerging amyloid pathology in Alzheimer’s disease. Front Neurosci. 2017;11:1–9.

Soldan A, Pettigrew C, Cai Q, Wang MC, Moghekar AR, O’Brien RJ, et al. Hypothetical preclinical Alzheimer disease groups and longitudinal cognitive change. JAMA Neurol. 2016;73(6):698–705.

Rentz DM, Parra Rodriguez MA, Amariglio R, Stern Y, Sperling R, Ferris S. Promising developments in neuropsychological approaches for the detection of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease: a selective review. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2013;5(6):58.

Papp KV, Rentz DM, Orlovsky I, Sperling RA, Mormino EC. Optimizing the preclinical Alzheimer’s cognitive composite with semantic processing: The PACC5. Alzheimer’s Dement Transl Res Clin Interv. 2017;3(4):668–77.

Mormino EC, Papp KV, Rentz DM, Donohue MC, Amariglio R, Quiroz YT, et al. Early and late change on the preclinical Alzheimer’s cognitive composite in clinically normal older individuals with elevated amyloid β. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13(9):1004–12.

Buckley RF, Maruff P, Ames D, Bourgeat P, Martins RN, Masters CL, et al. Subjective memory decline predicts greater rates of clinical progression in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12(7):796–804.

Lim YY, Snyder PJ, Pietrzak RH, Ukiqi A, Villemagne VL, Ames D, et al. Sensitivity of composite scores to amyloid burden in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease: introducing the Z-scores of Attention, Verbal fluency, and Episodic memory for Nondemented older adults composite score. Alzheimer’s Dement Diagn Assess Dis Monit. 2016;2:19–26.

Langbaum JB, Hendrix SB, Ayutyanont N, Chen K, Fleisher AS, Shah RC, et al. An empirically derived composite cognitive test score with improved power to track and evaluate treatments for preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10(6):666–74.

Amariglio RE, Becker JA, Carmasin J, Wadsworth LP, Lorius N, Sullivan C, et al. Subjective cognitive complaints and amyloid burden in cognitively normal older individuals. Neuropsychologia. 2012;50(12):2880–6.

Amariglio RE, Donohue MC, Marshall GA, Rentz DM, Salmon DP, Ferris SH, et al. Tracking early decline in cognitive function in older individuals at risk for Alzheimer’s disease dementia: the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study Cognitive Function Instrument HHS Public Access. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72(4):446–54.

Reisberg B, Prichep L, Mosconi L, John ER, Glodzik-Sobanska L, Boksay I, et al. The pre-mild cognitive impairment, subjective cognitive impairment stage of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2008;4(1 Suppl. 1):98–108.

Van Harten AC, Visser PJ, Pijnenburg YAL, Teunissen CE, Blankenstein MA, Scheltens P, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid Aβ42 is the best predictor of clinical progression in patients with subjective complaints. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9(5):481–7.

Stewart R, Godin O, Crivello F, Maillard P, Mazoyer B, Tzourio C, et al. Longitudinal neuroimaging correlates of subjective memory impairment: 4-year prospective community study. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;198(3):199–205.

Abdulrab K, Heun R. Subjective memory impairment. A review of its definitions indicates the need for a comprehensive set of standardised and validated criteria. Eur Psychiatry. 2008;23(5):321–30.

Jessen F, Amariglio RE, Van Boxtel M, Breteler M, Ceccaldi M, Chételat G, et al. A conceptual framework for research on subjective cognitive decline in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10(6):844-52.

Mitchell AJ, Beaumont H, Ferguson D, Yadegarfar M, Stubbs B. Risk of dementia and mild cognitive impairment in older people with subjective memory complaints: meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2014;130(6):439–51.

Ferreira D, Falahati F, Linden C, Buckley RF, Ellis KA, Savage G, et al. A “Disease Severity Index” to identify individuals with subjective memory decline who will progress to mild cognitive impairment or dementia. Sci Rep. 2017;7(September 2016):1–12.

Amariglio RE, Mormino EC, Pietras AC, Marshall GA, Vannini P, Johnson KA, et al. Subjective cognitive concerns, amyloid-β, and neurodegeneration in clinically normal elderly. Neurology. 2015;85(1):56–62.

Rabin LA, Smart CM, Crane PK, Amariglio RE, Berman LM, Boada M, et al. Subjective cognitive decline in older adults: an overview of self-report measures used across 19 international research studies. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;48(Suppl 1(0 1)):S63–86.

Gallassi R, Oppi F, Poda R, Scortichini S, Maserati MS, Marano G, et al. Are subjective cognitive complaints a risk factor for dementia. Neurol Sci. 2010;31(3):327-36.

van Oijen M, de Jong FJ, Hofman A, Koudstaal PJ, Breteler MMB. Subjective memory complaints, education, and risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2007;3(2):92-7.

Molinuevo JL, Rabin LA, Amariglio R, Buckley R, Dubois B, Ellis KA, et al. Implementation of subjective cognitive decline criteria in research studies. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13(3):296–311.

Koppara A, Wagner M, Lange C, Ernst A, Wiese B, König HH, et al. Cognitive performance before and after the onset of subjective cognitivedecline in old age. Alzheimer’s Dement Diagn Assess Dis Monit. 2015;1(2):194–205.

Jessen F, Wiese B, Bachmann C, Eifflaender-Gorfer S. Prediction of dementia by subjective memory impairment. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(4):414–22.

Dubois B. The emergence of a new conceptual framework for Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;62(3):1059–66.

Pike KE, Ellis KA, Villemagne VL, Good N, Chételat G, Ames D, et al. Cognition and beta-amyloid in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease: data from the AIBL study. Neuropsychologia. 2011;49(9):2384–90.

Hollands S, Lim YY, Buckley R, Pietrzak RH, Snyder PJ, Ames D, et al. Amyloid-β related memory decline is not associated with subjective or informant rated cognitive impairment in healthy adults. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;43(2):677–86.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000100.

Dubois B, Feldman HH, Jacova C, DeKosky ST, Barberger-Gateau P, Cummings J, et al. Research criteria for the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: revising the NINCDS-ADRDA criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6(8):734–46.

Hoy D, Brooks P, Woolf A, Blyth F, March L, Bain C, et al. Assessing risk of bias in prevalence studies: modification of an existing tool and evidence of interrater agreement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65(9):934–9.

Schwarzer G, Carpenter JR, Rücker G. Fixed effect and random effects meta-analysis. In: Meta-Analysis with R. Cham: Springer; 2015. p. 21-53.

Dubois B, Epelbaum S, Nyasse F, Bakardjian H, Gagliardi G, Uspenskaya O, et al. Cognitive and neuroimaging features and brain β-amyloidosis in individuals at risk of Alzheimer’s disease (INSIGHT-preAD): a longitudinal observational study. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(4):335–46.

Zhao Y, Tudorascu DL, Lopez OL, Cohen AD, Mathis CA, Aizenstein HJ, et al. Amyloid β deposition and suspected non-Alzheimer pathophysiology and cognitive decline patterns for 12 years in oldest old participants without dementia. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75(1):88–96.

Mandecka M, Budziszewska M, Barczak A, Pepłońska B, Chodakowska-Żebrowska M, Filipek-Gliszczyńska A, et al. Association between cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease, APOE genotypes and auditory verbal learning task in subjective cognitive decline, mild cognitive impairment, and Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;54(1):157–68.

Visser PJ, Verhey F, Knol DL, Scheltens P, Wahlund LO, Freund-Levi Y, et al. Prevalence and prognostic value of CSF markers of Alzheimer’s disease pathology in patients with subjective cognitive impairment or mild cognitive impairment in the DESCRIPA study: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8(7):619–27.

Vos SJB, Verhey F, Frölich L, Kornhuber J, Wiltfang J, Maier W, et al. Prevalence and prognosis of Alzheimer’s disease at the mild cognitive impairment stage. Brain. 2015;138(5):1327–38.

Palmqvist S, Zetterberg H, Mattsson N, Johansson P, Minthon L, Blennow K, et al. Detailed comparison of amyloid PET and CSF biomarkers for identifying early Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2015;85(14):1240–9.

Vos SJB, Xiong C, Visser PJ, Jasielec MS, Hassenstab J, Grant EA, et al. Preclinical Alzheimer’s disease and its outcome: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(10):957–65.

Vos SJB, Visser PJ. Preclinical Alzheimer’s disease: implications for refinement of the concept. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2018;64:S213–27.

Mattsson N, Insel PS, Donohue M, Landau S, Jagust WJ, Shaw LM, et al. Independent information from cerebrospinal fluid amyloid-β and florbetapir imaging in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2014;138(3):772-83.

Jansen WJ, Ossenkoppele R, Knol DL, Tijms BM, Scheltens P, Verhey FRJ, et al. Prevalence of cerebral amyloid pathology in persons without dementia: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2015;313(19):1924–38.

Mattsson N, Rich K, Kaiser E, Rikkert M. Age and diagnostic performance of Alzheimer disease CFS biomarkers. Neurology. 2012;78:468–76.

Jack CR, Therneau TM, Wiste HJ, Weigand SD, Knopman DS, Lowe VJ, et al. Transition rates between amyloid and neurodegeneration biomarker states and to dementia: a population-based, longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15(1):56–64.

Gordon BA, Najmi S, Hsu P, Roe CM, Morris JC, Benzinger TLS. The effects of white matter hyperintensities and amyloid deposition on Alzheimer dementia. NeuroImage Clin. 2015;8:246–52.

Arenaza-Urquijo EM, Bejanin A, Gonneaud J, Wirth M, La Joie R, Mutlu J, et al. Association between educational attainment and amyloid deposition across the spectrum from normal cognition to dementia: neuroimaging evidence for protection and compensation. Neurobiol Aging. 2017;59:72–9.

Snyder PJ, Johnson LN, Lim YY, Santos CY, Alber J, Maruff P, et al. Nonvascular retinal imaging markers of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement Diagn Assess Dis Monit. 2016;4(October):169–78.

Vassilaki M, Aakre JA, Mielke MM, Geda YE, Kremers WK, Alhurani RE, et al. Multimorbidity and neuroimaging biomarkers among cognitively normal persons. Neurology. 2016;86(22):2077–84.

Eckerström M, Göthlin M, Rolstad S, Hessen E, Eckerström C, Nordlund A, et al. Longitudinal evaluation of criteria for subjective cognitive decline and preclinical Alzheimer’s disease in a memory clinic sample. Alzheimer’s Dement Diagn Assess Dis Monit. 2017;8:96–107.

Knopman DS, Jack CR Jr, Wiste HJ, Weigand SD, Vemuri P, Lowe V. Short-term clinical outcomes for stages of NIA-AA preclinical Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2012;78:1576–82.

Perrotin A, La Joie R, de La Sayette V, Barré L, Mézenge F, Mutlu J, et al. Subjective cognitive decline in cognitively normal elders from the community or from a memory clinic: differential affective and imaging correlates. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13(5):550–60.

Stenset V, Hofoss D, Johnsen L, Skinningsrud A, Berstad AE, Negaard A, et al. White matter lesion severity is associated with reduced cognitive performances in patients with normal CSF Aβ42 levels. Acta Neurol Scand. 2008;118(6):373–8.

Opdebeeck C, Yates JA, Kudlicka A, Martyr A. What are subjective cognitive difficulties and do they matter? Age Ageing; 2018.

Barthel H, Gertz HJ, Dresel S, Peters O, Bartenstein P, Buerger K, et al. Cerebral amyloid-β PET with florbetaben (18F) in patients with Alzheimer’s disease and healthy controls: a multicentre phase 2 diagnostic study. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10(5):424–35.

Besson FL, La Joie R, Doeuvre L, Gaubert M, Mezenge F, Egret S, et al. Cognitive and brain profiles associated with current neuroimaging biomarkers of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2015;35(29):10402–11.

Brier MR, McCarthy JE, Benzinger TLS, Stern A, Su Y, Friedrichsen KA, et al. Local and distributed PiB accumulation associated with development of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2016;38:104–11.

Byun MS, Yi D, Lee DY, Kim HJ, Choi HJ, Lee JY, et al. Differential effects of blood insulin and HbA1c on cerebral amyloid burden and neurodegeneration in nondiabetic cognitively normal older adults. Neurobiol Aging. 2017;59:15–21.

Cho H, Choi JY, Hwang MS, Kim YJ, Lee HM, Lee HS, et al. In vivo cortical spreading pattern of tau and amyloid in the Alzheimer disease spectrum. Ann Neurol. 2016;80(2):247–58.

Clark LR, Berman SE, Norton D, Koscik RL, Jonaitis E, Blennow K, et al. Age-accelerated cognitive decline in asymptomatic adults with CSF β-amyloid. Neurology. 2018;90(15):e1306–15.

Harrington MG, Chiang J, Pogoda JM, Gomez M, Thomas K, Marion SDB, et al. Executive function changes before memory in preclinical Alzheimer’s pathology: a prospective, cross-sectional, case control study. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e79378.

Hatashita S, Yamasaki H. Clinically different stages of Alzheimer’s disease associated by amyloid deposition with [11C]-PIB PET imaging. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;21(3):995–1003.

Johnson KA, Sperling RA, Gidicsin C, Carmasin J, Maye J, Coleman RE, Reiman EM, Sabbagh MN, Sadowsky CH, Fleisher AS, Doraiswamy PM, Carpenter AP, Clark CM, Joshi AD, Lu M, Grundman M, Mintun MA, Pontecorvo MJ, Skovronsky DA-A study group. Florbetapir (F18-AV-450 PET to assess amyloid burden in Alzheimer’s disease dementia, mild cognitive impairment, and normal aging. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9(5):S72-83.

Lilamand M, Cesari M, del Campo N, Cantet C, Soto M, Ousset P-J, et al. Brain amyloid deposition is associated with lower instrumental activities of daily living abilities in older adults. Results from the MAPT Study. J Gerontol Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2016;71(3):391–7.

Lim HK, Nebes R, Snitz B, Cohen A, Mathis C, Price J, et al. Regional amyloid burden and intrinsic connectivity networks in cognitively normal elderly subjects. Brain. 2014;137(12):3327–38.

Meyer PF, Savard M, Poirier J, Labonté A, Rosa-Neto P, Weitz TM, et al. Bi-directional association of cerebrospinal fluid immune markers with stage of Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;63(2):577–90.

Montal V, Vilaplana E, Alcolea D, Pegueroles J, Pasternak O, González-Ortiz S, et al. Cortical microstructural changes along the Alzheimer’s disease continuum. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14(3):340–51.

Ossenkoppele R, Madison C, Oh H, Wirth M, Van Berckel BNM, Jagust WJ. Is verbal episodic memory in elderly with amyloid deposits preserved through altered neuronal function? Cereb Cortex. 2014;24(8):2210–8.

Rodrigue KM, Kennedy KM, Devous MD, Rieck JR, Hebrank AC, Diaz-Arrastia R, et al. β-amyloid burden in healthy aging: regional distribution and cognitive consequences. Neurology. 2012;78(6):387–95.

Schoonenboom NSM, Reesink FE, Verwey NA, Kester MI, Teunissen CE, Van De Ven PM, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid markers for differential dementia diagnosis in a large memory clinic cohort. Neurology. 2012;78(1):47–54.

Taylor MK, Sullivan DK, Swerdlow RH, Vidoni ED, Morris JK, Mahnken JD, et al. A high-glycemic diet is associated with cerebral amyloid burden in cognitively normal older adults. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2017;106(6):1463-70.

Um YH, Choi WH, Jung WS, Park YH, Lee CU, Lim HK. Whole brain voxel-wise analysis of cerebral retention of beta-amyloid in cognitively normal older adults using18F-florbetaben. Psychiatry Investig. 2017;14(6):883–6.

Van Harten AC, Smits LL, Teunissen CE, Visser PJ, Koene T, Blankenstein MA, et al. Preclinical AD predicts decline in memory and executive functions in subjective complaints. Neurology. 2013;81(16):1409–16.

Wolfsgruber S, Polcher A, Koppara A, Kleineidam L, Frölich L, Peters O, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers and clinical progression in patients with subjective cognitive decline and mild cognitive impairment. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;58(3):939–50.

Funding

Not applicable

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LP and EC drafted the manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript for content. LP, EC, and PE contributed to the study concept or design. All authors analyzed or interpreted data. EC, NS, KDA, and PE were responsible for acquisition of data. PE performed the statistical analysis. LP was responsible for study supervision or coordination. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Table S1. PRISMA Checklist. (DOC 63 kb)

Additional file 2:

Table S2. Cut-offs used for defining pre-clinical Alzheimer’s disease according biomarkers positivity. Table S3. Education years. (DOCX 53 kb)

Additional file 3:

Figure S1. Subgroup analysis according to mean age of participants. (PNG 1040 kb)

Additional file 4:

Table S4. Risk of Bias Assessment. (DOCX 45 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Parnetti, L., Chipi, E., Salvadori, N. et al. Prevalence and risk of progression of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease stages: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Alz Res Therapy 11, 7 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-018-0459-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-018-0459-7