Abstract

Purpose

To understand supportive care needs among people with non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC).

Methods

An integrative systematic review was reported using the Preformed Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. Seven electronic databases were searched for relevant studies, including all quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods studies, irrespective of research design. The review process was managed by Covidence systematic review software. Two reviewer authors independently performed data extraction using eligibility criteria. Quality appraisal was conducted, and a narrative synthesis was performed.

Results

A total of 1129 articles were screened, of which 21 studies met the inclusion criteria. The findings revealed that the frequency of supportive care needs reported by NMIBC participants included psychological/emotional (16/21:76%), physical (16/21:76%), practical (8/21:38%), interpersonal/intimacy (7/21:33%), family-related (7/21:33%), health system/information (5/21:23%), social (4/21:19%), patient-clinician communication (3/21:14%), spiritual (1/21:5%) and daily needs (1/21:5%).

Conclusion

People affected by NMIBC experience anxiety, depression, uncertainty, and fear of recurrence. The physical symptoms reported included urinary issues, pain, sleeping disorders and fatigue. These supportive care needs persist throughout the participants' treatment trajectory and can impact their quality of life.

Implications for Cancer Survivors

Identifying supportive care needs within the NMIBC population will help inform future interventions to provide patient-centred care to promote optimal well-being and self-efficacy for people diagnosed with NMIBC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Bladder cancer is the tenth most prominent cancer diagnosis globally and remains the most expensive cancer to treat [1], with approximately 550,000 individuals diagnosed yearly. The highest incidence rates occur in Europe and North America [2] and it is the eleventh-ranked cancer diagnosis in Australia. Most bladder tumours (75–80%) present as non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) [3,4,5,6].

The known causal risk factors of bladder cancer include smoking and occupational exposure to amines and other chemicals [7, 8]. Other causes that have been shown to increase the risk of bladder cancer include chronic urinary tract infections, previous radiotherapy to the pelvis, exposure to cyclophosphamide, and exposure to contaminated drinking water by parasites such as Schistosoma haematobium [2, 9].

The treatment for NMIBC involves a complete surgical transurethral resection of the bladder tumour. Further treatment decisions are then initiated based on the histology results of the resected tumour. Cancer staging depends on the pathological grading and the depth of the tumour [10]. Tumours are classified as NMIBC when there is no evidence of tumour invasion into the lamina propria. The categories of NMIBC include (1) Ta- (non-invasive papillary tumour), (2) Tis-(carcinoma in situ) and (3) T1- (tumour invades subepithelial connective tissue) [11, 12].

Treatment involves regular invasive surveillance and either intravesical immunotherapy or chemotherapy. High-grade tumours are treated with Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) with induction and maintenance courses or in combination with intravesical chemotherapy such as Mitomycin C [5, 6]. A prospective study by Grossman et al. (2022) found that the 5-year risk of recurrence or progression was high at 83% in patients with high-risk NMIBC [13]. The risk of NMIBC becoming muscle-invasive has been reported to be 20–25% during the patient’s lifetime [14]. Consequently, the burden of treatment regimens, coupled with frequent and invasive surveillance protocols, means that most patients are at risk of reduced quality of life, psychological challenges, and a range of unmet supportive care needs despite routine clinical follow-ups with healthcare professionals [5, 15, 16].

It has been suggested that more research focused on the quality of life and supportive care needs among people living with NMIBC [4, 5, 15], particularly for patients with high-risk NMIBC clinical features. Evidence has underscored that the bladder cancer research focus has focused on predominately muscle-invasive bladder cancer [17]. Furthermore, a systematic review [18] evidenced unmet supportive care needs exclusive to people affected by muscle-invasive bladder cancer, which therefore provides no insight into the needs of those affected by NMIBC.

A synthesis of current knowledge [19,20,21] has revealed that patients have reported a decreased quality of life following their initial diagnosis of NMIBC cancer. A decrease in quality of life is associated with distressing side effects of treatment and psychological issues such as anxiety, depression and uncertainty. Patients also experienced embarrassment due to the invasive nature of their surveillance procedures (i.e. cystoscopy procedures) [21].

Supportive care needs have been defined as the patient’s request for both general support or an identified problem prioritised by the individual when diagnosed or treated for cancer [19, 22]. Supportive care needs can occur from diagnosis through the treatment phase and into either the survivorship or palliative phases of the illness [21, 23]. Supportive care is classified into several domains: physical, emotional/psychological, cognitive, patient-clinician, health system/informational, spiritual, daily living, interpersonal, intimacy, practical and social needs [24, 25]. Timely identification of patients’ supportive care needs is paramount to ensure that patients receive optimised care to enhance health outcomes by addressing what matters most to cancer patients [23].

Several studies [19,20,21] have identified the relationship between unmet needs and reduced quality of life. Unmet supportive care needs may lead to emotional distress and higher symptom distress scores and can negatively impact patients’ coping abilities throughout their care trajectory [26,27,28,29]. These effects contribute to a diminished quality of life [20, 30, 31]. To date, the evidence has yet to be critically synthesised to understand the supportive care needs among people living with NMIBC specifically. Current knowledge in this area is timely and important to inform clinical practice, any requirements for service re-design, and future research directions.

Therefore, this integrative systematic review aimed to address the following research questions:

-

1.

What are the supportive care needs among people affected by NMIBC cancer?

-

2.

What are the frequently reported domains of supportive care needs among people affected by NMIBC?

Methods

This review was reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [32]. A review protocol was developed and registered with PROSPERO (CRD 42022332137).

Search strategy

The following electronic databases and register were searched by an expert systematic review librarian: APA PsycINFO, CINAHL, Cochrane Library (DSR and CENTRAL), MEDLINE, Scopus, and Web of Science Core Collection, date cut-off from inception to December 2022. See Supplementary Table 1 for the full search strategy.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

All studies were included if they investigated the supportive care needs among adults (> 18 years) diagnosed with NMIBC, including all qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods. Patients in mixed cancer groups were included only when separate subgroup analyses were reported for NMIBC participants.

Exclusion criteria

Studies where supportive care needs were not explicitly reported or conducted were excluded.

Study collection and data extraction

Screening process

All articles identified were imported into Endnote referencing software and exported to Covidence Systematic Review software (Covidence© 2020, Version 1517, Melbourne, Australia) for the removal of duplicates and the study selection process. The articles were screened, and two reviewers applied the inclusion criterion to all titles and abstracts and any conflicts were resolved by discussion. Reviewers then assessed the full-text articles, and disagreements were resolved through discussion. The study selection process was described using the PRISMA diagram [32]. Full-text studies that did not meet inclusion criteria were excluded with reasons.

Data extraction

One reviewer (KS) extracted study data, and a second reviewer (CP) checked for quality and accuracy. A data extraction table was developed and piloted in a sample of studies prior to data extracting for all of the studies. The data extraction table contained information about the participants' clinical and demographic characteristics, countries and institutions where data was collected, setting, sample size, study design, reports of supportive care needs, and the number of participants included in the studies. A second data extraction table was used for the qualitative data.

Quality assessment

The methodological quality and evaluation of the studies were assessed using the mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) [33]. The MMAT tool was selected for its versatility when assessing different study designs in this integrative review. The MMAT tool enabled critical assessment of quantitative, qualitative and mixed-method studies included in this review. All domains were assessed and rated against “no”, “yes”, and “unclear”. Methodological quality assessment was performed by one reviewer, and quality was checked by a second reviewer.

Data synthesis

This review used a narrative synthesis and tabulation of primary research studies to identify the supportive care needs of NMIBC population. The narrative synthesis included the following steps: data reduction (subgroup classification based on levels of evidence and research questions), data comparison (an iterative process of making comparisons and identifying relationships) and conclusion substantiation [34]. This approach has been used in several cancer systematic reviews [25, 31, 35] identifying supportive care needs among various cancer groups.

Operational definition of domains of need

Supportive care needs were categorised into eleven primary domains of need based on current literature, the seminal work of Fitch (2008), and clinical expertise. Specifically, the domains include physical, psychosocial/emotional, family-related, social, interpersonal/intimacy, practical, daily living, spiritual/existential, health system/information, patient/clinician communication, and cognitive needs [24, 25, 31] (see Fig. 2).

Findings

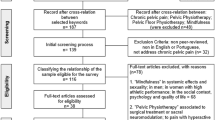

Figure 1 provides an overview of the screening and selection process. A total of 21 studies were included and met the inclusion criteria, and complete data extraction and quality assessment are presented in Supplementary Table 2.

PRISMA diagram [32]

Study characteristics

A total of 21 studies were included in this integrative review. See Table 1 for an overview of the studies. The various study designs that included the types of studies presented in this systematic review comprised: qualitative n = 2 [36, 37], quantitative n = 16 [26, 27, 29, 38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50] and n = 3 mixed methods [28, 51, 52]. This systematic review comprised 3654 participants: n = 2918 males, female n = 736. The sample sizes ranged from 6 to 868 participants. The studies included representation from several countries, including the USA, the UK, the Netherlands, China, Greece, Korea, and Japan. Noteworthy, there is no representation from the Australian or New Zealand populations. The median age of the patients was 67 years (min. = 46, max. = 89). Their clinical status included pathological grading of tumours as Ta- pT1 and carcinoma in situ. Eleven studies represented patients treated with BCG or intravesical chemotherapy [27, 29, 36, 38,39,40, 43, 44, 46, 48, 49].

Results of methodological quality assessment are presented in Table 2.

The studies included qualitative studies (n = 2), quantitative (n = 16) and mixed methods (n = 3). Overall, the methodological quality of the studies was credible, with only one study (Tan et al., 2020) that did not meet all the quality assessment criteria (Fig. 2).

Frequency of identified supportive care needs

The supportive care needs of the participants included in this review were classified according to the eleven domains (see Table 3). The supportive care needs comprised of the following in order of significance: psychological/emotional, n = 16/21: 76%, physical n = 16/21:76%, practical n = 8/21:38%, interpersonal/intimacy n = 7/21:33% and health system/informational n = 5/2:23%, social n = 4/21:19%, patient/clinician communication n = 3/21:14%, spiritual n = 2/21:9.5%, and daily living n = 1/21:5%. Participants enduring intravesical therapy had intimacy concerns [27, 45, 49] and fear of contaminating their partners [47, 51]. They also requested information and support to access sexual well-being interventions [27, 45, 47, 51].

Supportive care needs

Psychological/emotional needs

Psychological and emotional needs were prominent throughout this literature review, with sixteen out of twenty-one studies identifying them as prominent needs [27,28,29, 36, 38, 40, 41, 43, 44, 46, 47, 49,50,51,52,53]. Psychological and emotional symptoms were prevalent from the initial diagnosis and throughout their treatment and survivorship phases [28, 36, 37, 51, 52]. The participants who had either transurethral resection of bladder tumour and intravesical therapy reported anxiety, depression [28, 38] and uncertainty [15, 40]. Uncertainty was identified to be related to their initial diagnosis, treatment regime and fear of cancer recurrence [26, 38, 41, 43, 52, 54]. People with NMIBC were reported to have a unique burden due to the high recurrence rates and frequent invasive surveillance regimes, which elevated distress due to cancer-related uncertainty [5, 28, 40]. Many participants reported needing assistance making life decisions, such as treatment decisions and the potential support they may require during their treatment phase. These decisions were in the context of uncertainty, which impacted their psychological and emotional well-being [15].

In one study, Jung et al. (2022) reported that NMIBC individuals met at least one criterion for post-traumatic stress disorder. Post-traumatic stress disorder is defined as a harmful or life-threatening event that can impact an individual’s emotional, physical, social or spiritual well-being [40].

Post-traumatic stress symptoms (PTSS), particularly uncertainty, directly impacted NMIBC participants’ quality of life. Jung et al. (2022) reported that uncertainty in the NMIBC population is related to fear of recurrence and the long-term effects of treatments. The more uncertain patients felt, the greater their quality of life declined. Individuals with NMIBC with a higher uncertainty rate were identified predominately as younger male participants, unaware of their disease status, with lower social support and income [40].

Participants who received intravesical therapy reported a significant impact on their quality of life, experiencing greater depression and difficulty with emotional coping and physical well-being [38, 40, 52]. They also stated concerns about transmitting disease to their partners, especially when being intimate [51]. Many participants experienced shock, worry and anxiety with their initial diagnosis of bladder cancer [52].

“Yes. My emotional it affected my emotional well-being principally worry and anxiety” pg. 674 [52].

NMIBC participants reported using various coping strategies for their stress, including active coping, acceptance of their condition and using a sense of humour to cope with specific situations. Unhelpful strategies included denial, avoidance of the situation and substance abuse [29].

Physical needs

Physical symptoms were prominent across the majority of studies. Participants reported their main concerns were urinary symptoms [26, 42, 45, 48, 49], pain [38, 41, 48, 49, 54] sleep difficulties [28, 42, 45, 49] and fatigue [49, 55]. Individuals receiving intravesical therapy experienced fluctuating symptoms that were more significant whilst on treatment. Some participants expressed the impact of their urinary symptoms as painful; for some, they reported to have lasted 6–7 h, which impacted their quality of life [36]. Poor sleep quality was due to urinary symptoms such as nocturia, frequency, urgency and urinary incontinence [26, 28, 41, 42, 44, 54]. Urinary symptoms also affected participants’ ability to socialise with family and friends as they had to plan their activities around a bathroom location, sometimes opting not to engage in social outings [36].

Pain was commonly identified as a physical symptom for NMIBC participants [28, 38, 41, 42, 45, 49]. Individuals reported experiencing pain whilst enduring cystoscopy procedures for their surveillance protocol. Krajewski et al. (2017) reported that participants experienced more pain with a rigid cystoscopy than with a flexible cystoscopy. Participant pain was attributed to an association with recalled pain from previous cystoscopy experiences, which was increased slightly by the participants’ anxiety and anticipatory fear [41]. Some participants enduring intravesical therapy treatment experienced more significant pain post-treatment, which they did not expect. Participants commented that the patient information brochure did not detail this side effect [36, 48, 49].

“There are really painful downsides, and maybe the difference is that the literature says that there are downsides, but they don't say it can be quite traumatic …. This is one of the big problems it was that 6–7 h of intense pain …It was up at the higher level of pain than there was in the literature” pg. 109 [36].

Practical needs

Financial support was the greatest identified practical need within this review. The participants were representatives from various countries, including the UK, Canada, China, and the USA; despite these countries being developed, participants reported financial burden and the loss of work hours whilst having treatment for NMIBC [15, 38, 40, 45, 48]. Some NMIBC people experienced financial toxicity, which impacted their ability to work, mainly due to multiple outpatient visits for their treatment regimes. One study by Chung et al.(2019) (n = 586) reported that 66% of participants wanted assistance to access financial information [15]. Wei et al. (2014) reported that financial difficulties were present among participants commencing intravesical therapy prior to treatment and were significantly higher following treatment. This was attributed to increased urinary symptoms, discomfort and loss of productive work hours [48].

Catto et al. (2021) identified that NMIBC people less than 65 years old having transurethral resection of bladder tumours suffered from financial toxicity due to their treatment regime and inability to attend to their work. One study by Jung et al. (2022) reported that lower income was associated with a lower quality of life and higher uncertainty, leading to increased stress levels for the NMIBC participants [40]. In contrast, Koo et al.(2017) found that 73% of participants felt more capable of meeting work and home responsibilities following their treatment as they were aware of their treatment plan and did not have anxiety prior to treatment [28].

Interpersonal/intimacy needs

Non-muscle invasive bladder cancer people expressed a desire for assistance with sexual and intimacy needs [15, 38, 41, 45, 47, 49, 51]. One issue identified was the fear of contaminating their partner during sexual intercourse [37, 38, 47, 51]. Other issues included participants requiring assistance with relationships and strategies to assist with their partners’ understanding of their cancer [15, 38, 51]. A decline in sexual function and enjoyment was experienced by participants who were increasing in age and had other health conditions. Several participants experienced sexual dysfunction before diagnosis [38, 47, 51]. Sexual issues were identified as a concern in participants receiving intravesical therapy. In one cohort, 50% of participants aged 40–50,33%, 50–59, and 19% aged 70–79 experienced sexual issues that impacted their intimate relationships [49]. Women were less likely to be sexually active (56%) than men (31%), and those women who were sexually active experienced vaginal dryness [51]. In comparison, men experienced erectile and ejaculatory dysfunction [47, 51]. Participants on current intravesical treatment stated that it impacted their relationships due to their perceived loss of intimacy [51]. Some participants found sharing their sexual concerns with their partners was beneficial. Effective communication between the couple provided an opportunity to re-establish a sexual relationship following a diagnosis of NMIBC. At the same time, others reported difficulty initiating the conversation and sought professional assistance [51].

“Well, obviously, for sex, it's different. As far as the marriage goes, it really made it stronger. Like I said, she was there for me the whole time. And I think we bonded a little closer even. We've been married for [over two decades], so it's, I mean, we were pretty close before that. And obviously [bladder cancer] changed our sex life a little bit. We still have sex, but it's a little different now” pg.148 [51]

Family and related needs

Participants expressed the importance of family and support with their diagnosis and treatment [28, 37, 49, 51, 52, 54]. Those with family support reported higher quality of life scores [43]. Partners of people with NMIBC were identified as the primary support for their loved ones, offering practical support with managing appointments and helping with lifestyle changes, such as quitting smoking and encouraging physical exercise [37].

Some NMIBC participants waiting for treatment felt they were taking issues out on their support people, which intensified their feelings of guilt and anxiety. However, 82% felt improvement in their relationship with family and friends following their cystoscopy procedure [28]. There was an association between higher quality of life scores for people with NMIBC and those who reported having a supportive partner or family member. The benefit of their support is that people provide effective communication, assistance and support [43, 51, 52].

“I had a belief that I wouldn't succumb as in, you know, it wouldn't be fatal for me, but then I had to that kind of positive thing. I had positive thinking. I didn't really tell my kids too much. My sister is pretty sympathetic, my sister was pretty helpful” pg. 674 [52].

Health system and informational needs

Several studies reported a lack of information for participants [27, 28, 36, 44, 52, 53] and included sub-optimal support on managing physical symptoms and navigating the healthcare system [15, 36, 37, 44, 52]. Due to the continual surveillance protocols for people with NMIBC, timely information provided by healthcare professionals was paramount. Some patients experienced shock with their initial diagnosis having assumed it to be either a urinary tract infection or a prostate problem [52]. Other participants had seen television advertisements encouraging them to have their symptoms reviewed by a doctor [52]. One study by Richards et al. (2021) indicated that patients’ knowledge about smoking and its causal factor to NMIBC was poor [44].

Several participants felt the surveillance cystoscopy process could be improved by providing time to discuss findings and other lifestyle changes immediately following their procedure [37]. Some participants experienced anxiety and stress at the delay in their procedure [37] or the time in receiving their pathology results [28]. In contrast, patients who had subsequent follow-up consultations felt they understood the process and were less stressed. Understanding the processes and providing adequate time for discussion made the participants feel they were actively involved in their treatment process [52].

Social needs

Four studies [28, 36, 48, 49] acknowledged the impact of NMIBC treatment on participants’ social needs. Participants reported mutual feelings, including withdrawing from those close to them, which caused feelings of isolation [28]. Social interactions had decreased following post-intravesical therapy, often due to urinary symptoms and the requirement to be close to a bathroom [28, 36, 49]. Some participants described feeling isolated but preferred to stay at home as they did not want anyone to see them suffering from discomfort from their urinary symptoms [36].

“I had to be on the toilet or next to the toilet wearing incontinence pads because I couldn’t do anything… it has prevented me going out for a drink… knew every toilet on the (name of town) seafront. It’s pre-planning” pg. 109 [36]

Patient and clinician communication needs

Participants experienced both positive and negative interactions with healthcare professionals [28, 36, 37, 51, 52]. The interactions involved process factors such as the timing of their surveillance. Some participants wanted more control over their treatment regimes, particularly regarding the necessity and frequency of their surveillance cystoscopies [28]. They reported that they would like to be involved in making their treatment decisions regarding when they will have their follow-up cystoscopy; other participants were happy to leave this to the urologist [28].

Some participants experienced negative interactions with healthcare professionals, particularly after their surveillance cystoscopy. They would have liked a discussion and explanation of the findings immediately after their procedure, which did not always happen [37]. One participant was informed of her cancer diagnosis via email from another surgeon [37]. Some participants who received intravesical treatment during the BCG shortage were not given explanations of why they were receiving a different medication or a reduced amount of BCG. The lack of information about this change in their treatment regime resulted in feelings of anxiety and worry for NMIBC people [37].

The NMIBC participants experienced positive interactions with their healthcare professionals and had an improvement in their quality of life scores [43]. They were more likely to discuss and receive treatment for their urinary symptoms due to feeling comfortable with their healthcare professional [26]. Some individuals received an out-of-hours phone call from the treating physician and found reassurance in receiving this call [37]. Several participants expressed that they preferred continuity of care, having the same urologist or health care professional perform their surveillance cystoscopy. When this did not occur, it caused some participants increased anxiety. In contrast, others were comforted by having a “different set of eyes” to view their bladder pg.126 [28].

One study [53] suggested that having access to a healthcare professional was fundamental to rural patients when urologists and healthcare professionals are limited. Some participants described feelings of anxiety and concern with the lack of urologists, and others felt frustrated with the delay in waiting for their procedures [53]. Several participants appreciated having the telephone number of a nurse navigator to contact if they needed assistance or advice. Ensuring that patients had access to the point of care prevented hospital admissions, provided patient satisfaction and improved patient experiences for NMIBC participants [37].

Cognitive needs

Cognitive needs were identified in two studies [39, 40]. It was measured using the PROMIS (Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Applied Cognition-Abilities short form and PROMIS Applied General Concerns form. Cognition abilities refer to an individual’s capacity to plan, reason and understand complex ideas. It is often associated with positive connotations [56]. For participants with general cognition concerns, it is often associated with symptoms from their disease or treatment and can negatively affect the individual. The mean score ranges from 8 to 40, with the higher score indicating better cognitive function. For the participants included in this study (n = 376), the mean score (SD) was 31.9 (7.5) (SD) for cognition abilities [40]. NMIBC participants in this study reported a mean score of 14.4 (7.5) (SD) for general cognition concerns. Females affected by NMIBC reported higher levels of positive self-assessment of their cognitive functioning abilities, and this was associated with lower post-traumatic stress disorder and higher perceived quality of life scores. Participants who were currently having treatment had multiple comorbidities and more cognitive concerns and experienced a lower quality of life [40].

Spiritual needs

Only two studies identified spiritual needs in this review [36, 54]. Some participants identified spiritual needs as an excellent support, mainly assisting with their coping methods [36, 54]. Older participants with lower education levels were more likely to use religion as a coping strategy. Participants who experienced depressive symptoms were also weakly associated with using religion to cope [54]. Some participants gained strength from their church community, which made them feel psychologically and emotionally stronger to cope with their treatment [36].

Daily living needs

Across the studies, only one study, Koo et al. (2017), identified daily living needs as a concern. People affected by NMIBC expressed having difficulty performing daily activities such as housework or cooking before their cystoscopy procedure. Participants attributed the impact of stress, anxiety and feelings of apprehension prior to their treatment as the cause. These feelings were resolved following their treatment, and participants felt they could meet their home and work responsibilities [28].

Discussion

This integrative systematic review set out to identify the supportive care needs of people diagnosed with NMIBC and to report the most frequently reported needs in the literature. Identifying the supportive care needs will assist in guiding future interventions for service delivery. Supported care needs are defined as the individual’s request for general support or an identified problem prioritised by the individual when diagnosed or treated for cancer [19, 57]. Unmet supportive care needs refer to absence of or assistance in support of an identified problem of the NMIBC individuals. Unmet needs can occur from diagnosis throughout treatment and into survivorship or palliative phases [21]. NMIBC participants experienced a unique burden due to the numerous surveillance procedures required, high recurrence rate, and invasive treatments, such as cystoscopy and intravesical treatments. This systematic review identified psychological/emotional and physical domains as the foremost supportive care needs reported across the 21 studies. The NMIBC participants who were newly diagnosed or receiving intravesical therapy experienced more significant unmet needs, particularly with psychological (worry, anxiety, uncertainty and fear of cancer recurrence) and physical symptoms (pain urinary issues, and fear of contaminating their partners with intimacy).

Psychological and emotional needs have been identified as prominent in other reviews on genitourinary cancers [4, 18, 25, 35, 58, 59]. NMIBC participants experienced depression, anxiety and cancer-related uncertainty from diagnosis, throughout their treatment phase, and into survivorship. The feeling of uncertainty in illness pertains to the cognitive state or inability to determine or categorise an event or outcome that cannot be predicted accurately [60]. Cancer-related uncertainty affects the psychosocial adaptation and the effects of the disease on individuals [61]. The NMIBC participants reported enduring worry about cancer recurrence [26, 38, 41, 43, 52, 54]. There is a known relationship between uncertainty, emotional distress, and diminished quality of life which can produce increased anxiety and depression comparable to post-traumatic stress symptoms [39]. The emotional and psychological elements interrelate with other supportive care domains, providing a biopsychosocial model of care [22]. The biopsychosocial model encompasses physical, cognitive, spiritual, intimacy, family, and social needs among the NMIBC population. Healthcare professionals are uniquely positioned to promote screening and assessment of NMIBC people, using patient-reported outcomes measures (PROMS) that capture the physical, emotional/psychological, cognitive, patient-clinician interactions, health system/informational, spiritual, daily living, interpersonal, intimacy, practical and social domains of the needs individuals throughout their cancer continuum [4, 18, 62]. Routine screening for supportive care needs in clinical practice will identify and timely address NMIBC individuals’ unmet needs. Identifying the supportive care needs of this population provides a holistic approach to improving physical and mental well-being and quality of life among NMIBC participants [63].

Physical needs were primarily represented within the NMIBC population, with many participants reporting urinary symptoms as most bothersome [26, 42, 44, 45, 48]. Other symptoms reported included fatigue [49], pain [38, 41, 45, 48, 49, 54] and sleep deprivation [28, 49]. Preparing NMIBC individuals for the potential side effects of their treatment is paramount. Pre-treatment education should be provided using various learning styles; written, verbal, group, individual, and online formats; varying learning styles will promote knowledge and education to prepare NMIBC participants to shed light on uncertainties and assist in minimising their anxiety. Furthermore, it will promote identifying potential side effects of their treatment and timely interventions to assist with self-management [28, 52].

Financial toxicity was the greatest identified practical need within this integrative review. Financial toxicity refers to the financial burden and distress that can occur for patients and their family members as a result of their cancer treatment. It can impact all aspects of their cancer care, from imaging to medical therapy and long-term side effect management [64]. Financial difficulties were attributed to the long-term follow-up and frequent surveillance cystoscopies, which led to participants requiring time off work. Healthcare professionals must consider financial circumstances when developing future financial support interventions for NMIBC people. The impact of the increased cost of living worldwide due to the effects of the global COVID-19 pandemic, climate change and the war in Ukraine will continue to affect health care [65]. Reducing work hours and the rise in the cost of living will present a challenge for NMIBC patients in the future. Lower-income status has been identified as contributing to decreased quality of life and higher uncertainty, leading to increased patient stress levels [5]. Healthcare professionals must consider financial implications for NMIBC individuals when developing future supportive care interventions. It is paramount that NMIBC people are screened early in their care pathway with relevant patient-reported outcome measures to identify their risk of financial toxicity. Identifying individuals at risk will provide early intervention into the patient’s journey.

Health system, information and patient-clinician communication needs were reported to be less bothersome to NMIBC people in this systematic review. Other systematic reviews reporting on genitourinary cancers noted that health systems information and patient and clinician communications were considered a greater participant need [4, 18, 25, 31, 35, 58, 59]. Despite fewer NMIBC participants not reporting information and communication as a significant unmet need, it was still a concern for some individuals. Several participants experienced difficulty initiating sexual intimacy conversations with healthcare professionals due to embarrassment and a lack of support in accessing the interventions. Similar findings in other cancer populations have been well-documented in the literature [4, 18, 31, 35, 66]. A systematic review by Bessa et al. (2020) investigated the sexual health needs of bladder cancer patients. It revealed a paucity of studies, including the NMIBC population. Therefore, this current review provides new insights into the intimacy and interpersonal needs of the NMIBC population. Participants expressed a need for information on relationship strategies [27], initiating conversations with their partners and healthcare professionals [51] and guidance from healthcare professionals to assist in accessing interventions [27]. Some participants described positive interactions with clinician communication, such as being included in treatment decisions and receiving after-hours phone follow-ups [28, 37]. Other participants stated they wanted more information and communication regarding changes to their treatment regime [53]. Partners were identified as the primary support for NMIBC patients. Participants with family, peer and healthcare provider support reported improved quality of life [37, 43] and enhanced coping strategies [54].

Rural patients expressed that the lack of urologists and healthcare professionals in their community caused anxiety and concern. Participants appreciated the contact details of the nurse navigator. Nurse navigators provided patients satisfaction and timely response to patients’ concerns. Telephone consultations delivered by nurses have been utilised in the follow-up care of oncology patients since the late 1990s. A literature review by Cox et al. (2003) showed it to be acceptable, effective and appropriate for elderly and geographically isolated people [67]. It has become an essential element of clinical practice since the COVID-19 pandemic [68].

Limitations

Although this systematic review followed a registered priori protocol and a structured and rigorous process based upon the PRISMA guidelines to promote reproducibility, limitations were noted [32]. Most of the studies were cross-sectional, representing a snapshot in time and did not consider changes in supportive care needs over time. One of the challenges of this review was the heterogeneous methodologies, and our findings are constrained due to the methodological limitations of the studies included. This review only included articles in the English language and may have limited the applicability of our findings to other populations. One of the challenges of this review is that the NMIBC population includes patients with low-risk disease who require cystoscopy surveillance only, whilst other participants had high-risk NMIBC. The treatment approach will be more intensive with intravesical therapy for high-risk NMIBC people, and their supportive care needs may differ. However, this integrative review has facilitated a summation of the evidence for the supportive care needs of NMIBC, which have been absent in the current literature.

Clinical Implications and Conclusion

Non-muscle invasive bladder cancer is unique as it makes up the majority of bladder cancer diagnoses, requires lifetime surveillance, has a high recurrence rate and has uncertainty of prognosis. Previous studies have yet to identify the supportive care needs of the NMIBC population. This integrative review has highlighted the critical unmet needs of NMIBC participants. In particular, it has revealed that emotional, psychological and physical needs are currently not met. Nurses are at the forefront of the NMIBC participant’s healthcare journey and use patient-reported outcomes measures to identify their supportive care needs. Identifying participants’ supportive care needs requires regular screening, assessment, and timely intervention.

Future research should include regular assessment to review NMIBC individual’s supportive care needs (PROMS) throughout their cancer continuum, as supportive care needs are dynamic and may vary over time. Identifying the supportive care needs will contribute to developing future interventions to improve patients’ experiences living with a non-muscle invasive bladder cancer diagnosis.

Data availability

The data to support the findings of this study are available in the link titled supplementary information.

References

Lee LJ, Kwon CS, Forsythe A, Mamolo CM, Masters ET, Jacobs IA. Humanistic and economic burden of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: results of two systematic literature reviews. ClinicoEcon Outcomes Res. 2020;12:693.

Richters A, Aben KK, Kiemeney LA. The global burden of urinary bladder cancer: an update. World J Urol. 2020;38(8):1895–904.

Aapro M, Bossi P, Dasari A, Fallowfield L, Gascón P, Geller M, et al. Digital health for optimal supportive care in oncology: benefits, limits, and future perspectives. Kompass Nutr Diet. 2021;1(3):72–90.

Bessa A, Martin R, Häggström C, Enting D, Amery S, Khan MS, et al. Unmet needs in sexual health in bladder cancer patients: a systematic review of the evidence. BMC Urol. 2020;20(1):1–16.

Jung A, Nielsen ME, Crandell JL, Palmer MH, Bryant AL, Smith SK, et al. Quality of life in non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer survivors: a systematic review. Cancer Nurs. 2019;42(3):E21–33.

Sylvester RJ, Rodríguez O, Hernández V, Turturica D, Bauerová L, Bruins HM, et al. European Association of Urology (EAU) prognostic factor risk groups for non–muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) incorporating the WHO 2004/2016 and WHO 1973 classification systems for grade: an update from the EAU NMIBC Guidelines Panel. Eur Urol. 2021;79(4):480–8.

Mossanen M. The epidemiology of bladder cancer. Hematol/Oncol Clin. 2021;35(3):445–55.

Saginala K, Barsouk A, Aluru JS, Rawla P, Padala SA, Barsouk A. Epidemiology of bladder cancer. Med Sci. 2020;8(1):15.

Botelho MC, Alves H, Richter J. Halting Schistosoma haematobium-associated bladder cancer. Int J Cancer Manag. 2017;10(9):1–6.

Soukup V, Čapoun O, Cohen D, Hernandez V, Babjuk M, Burger M, et al. Prognostic performance and reproducibility of the 1973 and 2004/2016 World Health Organization grading classification systems in non–muscle-invasive bladder cancer: a European Association of Urology Non-muscle Invasive Bladder Cancer Guidelines Panel systematic review. Eur Urol. 2017;72(5):801–13.

Babjuk M, Burger M, Compérat EM, Gontero P, Mostafid AH, Palou J, et al. European Association of Urology guidelines on non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (TaT1 and carcinoma in situ)-2019 update. Eur Urol. 2019;76(5):639–57.

Chang S, Boorjian S, Chou R, Clark PE, Daneshmand S, Konety BR, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: AUA/SUO Guideline. J Urol. 2016;196(4):1021–9.

Grossmann NC, Rajwa P, Quhal F, König F, Mostafaei H, Laukhtina E, et al. Comparative outcomes of primary versus recurrent high-risk non–muscle-invasive and primary versus secondary muscle-invasive bladder cancer after radical cystectomy: results from a retrospective multicenter study. Eur Urol Open Sci. 2022;39:14–21.

Yuen JW, Wu RW, Ching SS, Ng C-F. Impact of effective intravesical therapies on quality of life in patients with non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(17):10825.

Chung J, Kulkarni GS, Morash R, Matthew A, Papadakos J, Breau RH, et al. Assessment of quality of life, information, and supportive care needs in patients with muscle and non-muscle invasive bladder cancer across the illness trajectory. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(10):3877–85.

Nayak A, Cresswell J, Mariappan P. Quality of life in patients undergoing surveillance for non-muscle invasive bladder cancer—a systematic review. Translat Androl Urol. 2021;10(6):2737.

McConkey RW, Dowling M. Supportive care needs of patients on surveillance and treatment for non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2021;37(1): 151105.

Paterson C, Jensen B, Jensen J, Nabi G. Unmet informational and supportive care needs of patients with muscle invasive bladder cancer: a systematic review of the evidence. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2018;35:92–101.

Faller H, Hass HG, Engehausen D, Reuss-Borst M, Wöckel A. Supportive care needs and quality of life in patients with breast and gynecological cancer attending inpatient rehabilitation A prospective study. Acta Oncol. 2019;58(4):417–24.

Molassiotis A, Yates P, Li Q, So W, Pongthavornkamol K, Pittayapan P, et al. Mapping unmet supportive care needs, quality-of-life perceptions and current symptoms in cancer survivors across the Asia-Pacific region: results from the International STEP Study. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(10):2552–8.

Okediji PT, Salako O, Fatiregun OO. Pattern and predictors of unmet supportive care needs in cancer patients. Cureus. 2017;9(5):e1234.

Olver I, Keefe D, Herrstedt J, Warr D, Roila F, Ripamonti CI. Supportive care in cancer—a MASCC perspective. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28:3467–75.

Krishnasamy M, Hyatt A, Chung H, Gough K, Fitch M. Refocusing cancer supportive care: a framework for integrated cancer care. Support Care Cancer. 2023;31(1):14.

Fitch M. Supportive care framework. Can Oncol Nurs J. 2008;18(1):6–14.

Paterson C, Primeau C, Bowkerm M, Jensen B, MacLennan S, Yuan Y, et al. What are the unmet supportive care needs of men affected by penile cancer? A systematic review of the empirical evidence. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2020;48: 101805.

Brisbane WG, Holt SK, Winters BR, Gore JL, Walsh TJ, Wright JL, et al. Nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer influences physical health related quality of life and urinary incontinence. Urology. 2019;125:146–53.

Chung J, Kulkarni GS, Morash R, Matthew A, Papadakos J, Breau RH, et al. Assessment of quality of life, information, and supportive care needs in patients with muscle and non-muscle invasive bladder cancer across the illness trajectory. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27:3877–85.

Koo K, Zubkoff L, Sirovich BE, Goodney PP, Robertson DJ, Seigne JD, et al. The burden of cystoscopic bladder cancer surveillance: anxiety, discomfort, and patient preferences for decision making. Urology. 2017;108:122–8.

Mazur M, Chorbińska J, Nowak Ł, Halska U, Bańkowska K, Sójka A, et al. Methods of coping with neoplastic disease in men with non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Int J Urol Nurs. 2022;17(1):29–38.

Cochrane A, Woods S, Dunne S, Gallagher P. Unmet supportive care needs associated with quality of life for people with lung cancer: a systematic review of the evidence 2007–2020. Eur J Cancer Care. 2022;31(1): e13525.

Paterson C, Toohey K, Bacon R, Kavanagh PS, Roberts C. What are the unmet supportive care needs of people affected by cancer: an umbrella systematic review. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2023;39(3):151353.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2021;10(1):1–9.

Hong QN, Fàbregues S, Bartlett G, Boardman F, Cargo M, Dagenais P, et al. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ Inf. 2018;34(4):285–91.

Whittemore R, Knafl K. The integrative review: updated methodology. J Adv Nurs. 2005;52(5):546–53.

Doyle R, Craft P, Turner M, Paterson C. Identifying the unmet supportive care needs of individuals affected by testicular cancer: a systematic review. J Cancer Surviv. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-022-01219-7.

Alcorn J, Burton R, Topping A. Withdrawing from treatment for Bladder cancer: patient experiences of BCG installations. Int J Urol Nurs. 2020;14(3):106–14.

Garg T, Johns A, Young AJ, Nielsen ME, Tan H-J, McMullen CK, et al. Geriatric conditions and treatment burden following diagnosis of non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer in older adults: a population-based analysis. J Geriatric Oncol. 2021;12(7):1022–30.

Catto JW, Downing A, Mason S, Wright P, Absolom K, Bottomley S, et al. Quality of life after bladder cancer: a cross-sectional survey of patient-reported outcomes. Eur Urol. 2021;79(5):621–32.

Jung A, Crandell JL, Nielsen ME, Mayer DK, Smith SK. Post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms in non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer survivors: a population-based study. Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations. 2021;39(4):237.e7-.e14.

Jung A, Crandell JL, Nielsen ME, Smith SK, Bryant AL, Mayer DK. Relationships among uncertainty, post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms, and quality of life in non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2022;30(7):6175–85.

Krajewski W, Kościelska-Kasprzak K, Rymaszewska J, Zdrojowy R. How different cystoscopy methods influence patient sexual satisfaction, anxiety, and depression levels: a randomized prospective trial. Qual Life Res. 2017;26:625–34.

Miyake M, Nishimura N, Oda Y, Owari T, Hori S, Morizawa Y, et al. Intravesical Bacillus Calmette-Guerin treatment-induced sleep quality deterioration in patients with non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: functional outcome assessment based on a questionnaire survey and actigraphy. Support Care Cancer. 2022;30(1):887–95.

Park J, Choi YD, Lee K, Seo M, Cho A, Lee S, et al. Quality of life patterns and its association with predictors among non-muscle invasive bladder cancer survivors: a latent profile analysis. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs. 2022;9(6): 100063.

Richards HL, Sweeney P, Corscadden R, Carr C, Rukundo A, Fitzgerald J, et al. “Picture this”-patients’ drawings of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: a novel method to help understand how patients perceive their condition. Bladder Cancer. 2021;7(2):149–59.

Smith AB, McCabe S, Deal AM, Guo A, Gessner KH, Lipman R, et al. Quality of life and health state utilities in bladder cancer. Bladder Cancer. 2022;8(1):55–70.

Vaioulis A, Bonotis K, Perivoliotis K, Kiouvrekis Y, Gravas S, Tzortzis V, et al. Quality of life and anxiety in patients with first diagnosed non-muscle invasive bladder cancer who receive adjuvant bladder therapy. Bladder Cancer. 2021;7(3):297–306.

Van Der Aa MN, Bekker MD, Van Der Kwast TH, Essink-Bot ML, Steyerberg EW, Zwarthoff EC, et al. Sexual function of patients under surveillance for bladder cancer. BJU Int. 2009;104(1):35–40.

Wei L, Li Q, Liang H, Jianbo L. The quality of life in patients during intravesical treatment and correlation with local symptoms. J Chemother. 2014;26(3):165–8.

Wildeman SM, van Golde C, Nooter RI. Psychosocial issues during the treatment of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. Int J Urol Nurs. 2021;15(1):12–9.

Zhang Z, Yang L, Xie D, Wang Y, Bi L, Zhang T, et al. Illness perceptions are a potential predictor of psychological distress in patients with non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: a 12-month prospective, longitudinal, observational study. Psychol Health Med. 2020;25(8):969–79.

Kowalkowski MA, Chandrashekar A, Amiel GE, Lerner SP, Wittmann DA, Latini DM, et al. Examining sexual dysfunction in non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: results of cross-sectional mixed-methods research. Sexual Med. 2014;2(3):141–51.

Tan WS, Teo CH, Chan D, Ang KM, Heinrich M, Feber A, et al. Exploring patients’ experience and perception of being diagnosed with bladder cancer: a mixed-methods approach. BJU Int. 2020;125(5):669–78.

Garg T, Connors JN, Ladd IG, Bogaczyk TL, Larson SL. Defining priorities to improve patient experience in non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. Bladder Cancer. 2018;4(1):121–8.

Mazur M, Chorbińska J, Nowak Ł, Halska U, Bańkowska K, Sójka A, et al. Methods of coping with neoplastic disease in men with non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Int J Urol Nurs. 2023;17(1):29–38.

Vaioulis A, Konstantinos B, Perivoliotis K, Yiannis K, Stavros G, Vasilios T, et al. Quality of life and anxiety in patients with non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: a prospective study. Bladder Cancer. 2021;7(3):297–306.

Lai JS, Wagner LI, Jacobsen PB, Cella D. Self-reported cognitive concerns and abilities: two sides of one coin? Psychooncology. 2014;23(10):1133–41.

Olver I, Keefe D, Herrstedt J, Warr D, Roila F, Ripamonti CI. Supportive care in cancer—a MASCC perspective. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28(8):3467–75.

O’Dea A, Gedye C, Jago B, Paterson C. Identifying the unmet supportive care needs of people affected by kidney cancer: a systematic review. J Cancer Surviv. 2022;16(6):1279–95.

Paterson C, Robertson A, Smith A, Nabi G. Identifying the unmet supportive care needs of men living with and beyond prostate cancer: a systematic review. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2015;19(4):405–18.

Mishel MH. Uncertainty in illness. Image: J Nurs Scholar. 1988;20(4):225–32.

McCormick KM. A concept analysis of uncertainty in illness. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2002;34(2):127–31.

Rutherford C, Patel MI, Tait M-A, Smith DP, Costa DS, Sengupta S, et al. Patient-reported outcomes in non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: a mixed-methods systematic review. Qual Life Res. 2021;30(2):345–66.

Pham H, Torres H, Sharma P. Mental health implications in bladder cancer patients: a review. Urologic Oncol: Seminars Orig Investig. 2019;37(2):97–107.

Abrams HR, Durbin S, Huang CX, Johnson SF, Nayak RK, Zahner GJ, et al. Financial toxicity in cancer care: origins, impact, and solutions. Translat Behav Med. 2021;11(11):2043–54.

Health TLP. The cost of living: an avoidable public health crisis. Lancet Public Health. 2022;7(6): e485.

Schubach K, Niyonsenga T, Turner M, Paterson C. Experiences of sexual well-being interventions in males affected by genitourinary cancers and their partners: an integrative systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2023;31(5):265.

Cox K, Wilson E. Follow-up for people with cancer: nurse-led services and telephone interventions. J Adv Nurs. 2003;43(1):51–61.

Fisk M, Livingstone A, Pit SW. Telehealth in the context of COVID-19: changing perspectives in Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(6): e19264.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions Supported by an Australian and New Zealand Urogenital and Prostate Cancer Trials Group (ANZUP) Research Scholarship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Kathryn Schubach: Conceptualisation, methodology, validation, screening, data extraction, formal analysis, interpretation, writing an original draft.

Theo Niyonsenga: Supervision, methodology, interpretation, proof-reading the manuscript.

Murray Turner: Literature searches, writing an original draft.

Catherine Paterson: Conceptualisation, methodology, validation, screening, data extraction, formal analysis, interpretation, writing an original draft, supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Schubach, K., Niyonsenga, T., Turner, M. et al. Identifying the supportive care needs of people affected by non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: An integrative systematic review. J Cancer Surviv (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-024-01558-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-024-01558-7