Abstract

Background

Bladder cancer (BC) treatment can have a detrimental effect on the sexual organs of patients and yet assessment of sexual health needs has been greatly overlooked for these patients compared to those who have undergone other cancer therapies.

Methods

This review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines in July 2019. Studies were identified by conducting searches for Medline (using the PubMed interface), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and Ovid Gateway (Embase and Ovid) using a list of defined search terms.

Results

15 out of 37 studies included men only, 10 studies women only and 11 both sexes. Most participants were aged 50 to 65 years. Most studies (n = 34) focused on muscle invasive BC and only three on non-muscle invasive BC. Measurements of sexual dysfunction, including erection, ejaculation, firmness and desire, were the most commonly used measurements to report sexual health in men. In women, lubrification/dryness, desire, orgasm and dyspareunia were the most commonly reported. Twenty-one studies evaluated sexual dysfunction based on validated questionnaires, two with a non-validated questionnaire and through interviewing participants.

Conclusion

While recognition of the importance of the inclusion of psychometric measurements to assess sexual health is growing, there is a lack of consistent measures to assess sexual health in BC. With the focus on QoL arising in cancer survivorship, further studies are needed to develop, standardize and implement use of sexual health questionnaires with appropriate psychometrics and social measures to evaluate QoL in BC patients.

Trial registration

“PROSPERO does not currently accept registrations for scoping reviews, literature reviews or mapping reviews. PROSPERO is therefore unable to accept your application or provide a registration number. This decision should not stop you from submitting your project for publication to a journal.”

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

It is well known that the diagnosis and treatment of cancer causes significant physical, psychological, and social effects that interfere with a person’s sexual health. Indeed, it has been estimated that between 40 and 100% of cancer patients will experience a degree of sexual dysfunction [1]. Sexual dysfunction is characterized by disturbances in sexual desire and in the psychophysiological changes associated with the sexual response cycle in men and women or pain during intercourse [2, 3]. The degree to which sexual dysfunction has been studied in different cancer types varies, with most studies performed in patients with prostate, breast or gynaecological cancers. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines sexual health as a state of physical, emotional, mental, and social wellbeing related to sexuality, and is not merely the absence of disease, dysfunction or infirmity [4]. Therefore, sexual health has to be evaluated holistically due to the complex interactions between biological, psychological, interpersonal and social/cultural factors [5], as all these factors may effect sexual function and wellbeing [6].

Bladder cancer (BC) treatments are known to have a potential detrimental effect on both the genitals and the internal sexual organs of patients and yet it has been greatly overlooked compared to other cancer therapies [7]. Research of the treatment impact on sexual health has been widely identified as an unmet need in bladder cancer patients [8, 9].

Non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) accounts for about 70% of all bladder cancers [10] and those are mostly treated with transurethral resection of the bladder tumor (TURBT), followed by intravesical chemotherapy (22%) or immunotherapy with bacillus CalmetteGuerin (BCG, 29%) [11]. Muscle invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) are commonly treated with cystectomy [11, 12]. The vast majority of studies currently available for bladder cancer focus on those who have undergone a radical cystectomy. Among those, many studies evaluate sexual-sparing radical cystectomy with the goal of reaching definitive oncologic control while attempting preservation of sexual function [13].

Current European Association of Urology (EAU 2019) guidelines [14] recommend that a standard radical cystectomy in men should include removal of the bladder, prostate, seminal vesical, distal ureters and regional lymph nodes, while in women removal of the bladder, entire urethra and adjacent vagina, uterus, distal ureters and regional lymph nodes is recommended. The guidelines also stated that a prostate-sparing radical cystectomy could be considered in carefully selected patients if oncologically safe. However, a sexual organ preserving operation in women is not advised, largely due to a paucity of available evidence [14]. Such treatments can induce serious complications and greatly impact the patient’s body image and quality of life (QoL) [11]. Health-related QoL (HRQoL) can be formally defined as the extent to which one’s usual or expected physical, emotional, and social wellbeing are affected by a medical condition or its treatment [15]. HRQoL issues of special concern to patients with BC include, among others, threats to body image and sexuality [16, 17].

With the focus on HRQoL arising in cancer survivorship, it is needed to closely address and evaluate post-treatment sexual dysfunction and offer goal-directed treatment. To date no detailed assessment of the overall burden of sexual health in bladder cancer patients has been made. This systematic literature review aimed to provide a consolidated overview of studies that address sexual health in bladder cancer patients. We specifically aimed to assess the methodology used to evaluate sexual health in terms of coverage and validation after BC treatment, which may provide a basis for future studies.

Methods

This review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines in July 2019. A detailed overview of the protocol is provided in Appendix 1.

Search strategy and inclusion criteria

Studies were identified by conducting searches for Medline (using the PubMed interface), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and Ovid Gateway (Embase and Ovid) between May and July 2019 using a list of defined search terms (see Appendix 2). To be included in the analysis, the studies must have met the following criteria: study on the impact of bladder cancer treatment on sexual health/dysfunction and reported outcomes specifically for sexual health/dysfunction (e.g. erection, ejaculation, dryness).

Data collection and analysis

Initially, the titles of the studies were screened to identify the relevant studies. The abstracts and subsequently full texts were then carefully read to identify those which met the inclusion criteria. Two independent reviewers (AB and RM) used the exact same search strategy and inclusion criteria and after each screening phase, a discussion was conducted with a third party (MVH) to match and decide on the included studies. Information on patient characteristics, number of study participants and type of treatment, as well as sexual health outcomes and mental wellbeing information was extracted from each study. The latter data was collected as sexual dysfunction may also have an impact on HRQoL through effects on mental wellbeing (4). The references of the included studies were also reviewed to ensure no relevant citation was missed.

Results

Quantity of evidence identified

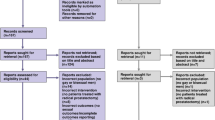

The selection process for records to be included in the review was carried out according to PRISMA protocol, and this is demonstrated in a PRISMA flowchart in Fig. 1. A total of 667 records were collected from the literature search and 108 duplicates were removed. All titles were initially screened and 226 remained for abstracts screening. Of those, 71 remained for full text analysis. After the full text was read, 37 studies matched the inclusion and exclusion criteria and were included in this systematic review (Table 1, Appendix 3).

Characteristics of the patient profiles

Of the 37 studies included in the systematic review, 15 studies (40.5%) included men only, 10 studies (27.0%), women only and 12 studies (32.4%) included both sexes. The exact number of women and men in the studies that included both sexes is not clearly described for all studies. With respect to age, in 28 studies (75.6%) participants were aged between 50 to 65 years, in five studies (13.5%) 26 to 49 years, in four studies (10.8%) 66 to 80 years and none included participants above 80 years old. The vast majority of studies [n = 34 (91.9%)] included MIBC and only three (8.10%) focused on NMIBC. Patient profiles for each study are described in Table 1.

Measurement of sexual health by sex

Measurements of sexual dysfunction, including erection (73.0%), ejaculation (35.1%), firmness (8.10%) and desire (18.9%), were the most commonly used measurements to report sexual health in men. In women, lubrification/dryness (27.0%), desire (24.3%), orgasm (27.0%) and dyspareunia (29.7%) were the most commonly reported (Table 2).

Comparison of sexual dysfunction outcome by treatments and measurements

Thirty-three (89.2%) studies addressed sexual dysfunction following radical cystectomy, one (2.7%) following radical radiotherapy, one (2.7%) after cystoscopy, and two (5.4%) after other treatments for bladder cancer. There are no studies looking at TURBT only. In four studies (10.8%), participants were treated with drug therapy for their sexual dysfunction. Twenty-one studies (56.8%) evaluated sexual dysfunction based on validated questionnaires, two (5.4%) with a non-validated questionnaire and 14 (37.8%) through interviewing participants.

Patient and partners sexual satisfaction and mental wellbeing

Seven studies evaluated patient sexual satisfaction and mental wellbeing (Table 3). None of those included both patient and partner satisfaction and mental wellbeing. One study included sexual satisfaction for both patients and partners, but did not report on mental wellbeing [18]. Regarding mental wellbeing, perception of body image [20, 22, 24], worry about daily life [19], feeling of anxiety [23] and depression [22] were the most commonly reported outcomes. Six of those studies included patients with MIBC and one NMIBC. Six studies included patients in the age range of 50–65 years and two included patients 66–80 years old. Overall, radical cystectomy was found to be associated with negative feelings regarding patient’s body image and consequently a negative effect in sexual satisfaction. Patients who underwent a bladder sparing technique had a better perception of their body and a better sexual satisfaction. There is no consistency in the measurements used for sexual satisfaction and/or mental wellbeing: interviews and semi-structured interviews, sexual function index questionnaire, QoL questionnaire (SHIM and IFSF) and a functional assessment of cancer therapy questionnaire.

Discussion

Sexual dysfunction is a common phenomenon after bladder cancer treatment and yet sexual health is frequently overlooked. Of the 37 included studies included in our review, 15 studies included men only, 10 studies included women only and 12 studies included both sexes. Most studies included participants aged between 50 to 65 years. The majority of studies focused on patients with MIBC. The main outcomes measured in men were erection, ejaculation and desire and in women, lubrification/dryness, orgasm and dyspareunia. A broad range of measures were used in the studies including validated patient reported outcome tools, such as the SHIM and the IFSF questionnaire and interview-based studies.

One of the main observations following our systematic review is the heterogeneity in measurements used for sexual health. The SHIM tool is commonly used in prostate cancer and has also been most commonly used in the studies identified here. In female patients the available measurement tools are broader and less commonly implemented in practice. The most commonly used tool we found was the IFSF questionnaire. Both tools have been criticised for their lack of psychometric measures [25]. Indeed, the need for a robust measure of sexual function in bladder cancer that includes psychometric assessment is well recognised, but not yet developed [26]. Mohamed et al. (2014) identified unmet needs in MIBC patients and sexual function was a significant concern [8]. With no evidence of consistent clinical measures from practice, these findings are unsurprising. Patient and public involvement is needed to develop and include appropriate psychometrics measures in sexual health questionnaires. As previously noted by Peter Selby and Galina Velikova [27], patient input is essential, but the process is time consuming, sometimes quite expensive and can involve large numbers of patients or the general population to achieve meaningful results. Therefore, individuals and groups have tended to develop their own questionnaires which led to a lack of general consensus in the field and a confusing number of questionnaires.

Moreover, our systematic review highlights how sexual health may negatively impact on mental wellbeing and HRQoL – and hence indicates the need to address this gap for patients. As suggested by the definition of the WHO [4], sexual health has to be evaluated from a psychosocial perspective and not only the physical and physiological aspects. Although erectile dysfunction in men and physical and physiologic changes associated with cystectomy in women are the dominant factor driving sexual function, other causes of sexual dysfunction, such as depression or anxiety related to changed body image, distress regarding partner reaction to an altered body as well as the degree of problems that patients are experiencing due to their sexual function (bother), should be evaluated and managed.

Currently, HRQOL questionnaires like the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – Bladder Cancer (FACT-BC) do include questions about interest in sex, while the Bladder Cancer Index (BCI) also includes questions about desire, arousal, sensation, and orgasm. Several EORTC questionnaires include a limited number of sexual functioning items. However, there is no single self-reported measure that covers the entire range of sexual health. Recently, the European Organization on Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) developed an EORTC Sexual Health Questionnaire (EORTC SHQ-22) for assessing sexual health in cancer patients [28]. In addition to that, HRQOL assessment should target patient’s current or very recent HRQOL status. This is of interest as (1) it has been suggested that patients overestimate their baseline HRQOL in the sexual function domains by 27% [29]; and (2) it would allow to better understand the degree of problems experienced by patients (measuring “bother”). It is also important to note that function and bother do not necessarily correlate as demonstrated by Letwin et al. [30] and that despite sexual health issues being an important concern to patients, they often experience difficulties in disclosing their complaints with health care providers or their partners. Lastly, as sexual wellbeing is closely correlated with social interactions, patients’ relationship status should also be considered when evaluating sexual wellbeing and its impact on HRQOL.

In our systematic review, most studies addressed sexual health in patients with MIBC who underwent radical cystectomy and only four studies focused on patients with NMIBC. This is potentially affecting the generalisibility of our observations as it is important to note that treatments for NMIBC and MIBC substantially differ, e.g. TURBT vs cystectomy. In a prospective study by Yoshimura et al. [31] on the impact of TURBT on QoL in patients with NMIBC, physical problems were found with the first TURBT, but when the fourth TURBT was performed, patients appeared to have adapted to frequent operations, although their general QoL remained affected. For cystectomy patients, it has been shown that although relationships with friends were unchanged, relationships with spouse or partner were disturbed by sexual problems [32]. Partner response to the presence of an external appliance, such as stoma, may also strain intimate relationships and contribute to a dysfunctional sex life. Nevertheless, these observations highlight that 1) the threat of recurrence, multiple cystoscopies, TURBT, and intravesical instillations make QoL assessment in superficial bladder cancer challenging; 2) the importance of looking at sexual function in patients with bladder cancer in a broader way is needed, i.e. including both the physical perspective as well as the patients’ partner and relationships.

There are limitations of this study that warrant further discussion. The analysis of the included studies was unable to provide an extensive coverage of sexual health in NMIBC patients for which the impact of treatment in sexual health and consequently QoL may also be significative. Due to the nature of the methods used to measure sexual health and the lack of psychometric measures, further research is needed to better understand the role of bladder cancer treatment and psychosocial factors of sexual functioning.

Conclusion

While recognition of the importance of the inclusion of psychometric measurements to assess sexual health is growing, this systematic review highlights the lack of consistent measures to assess sexual health in bladder cancer patients. With the focus on HRQoL arising in cancer survivorship, further studies are needed to develop, standardize and implement the use of sexual health questionnaires with appropriate psychometrics and social measures for bladder cancer patients.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- BC:

-

Bladder cancer

- BCG:

-

Bacillus Calmette–Guérin

- QoL:

-

Quality of life

- NMIBC:

-

Non-muscle invasive bladder cancer

- MIBC:

-

Muscle invasive bladder cancer

- HRQoL:

-

Health-related quality of life

- EORTC :

-

European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer

- EORTC SHQ-22:

-

European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Sexual health questionnaire - 22

- TURBT:

-

Trans urethral resection of bladder tumour

- IFSF:

-

Index of Female Sexual Function

- SHIM:

-

Sexual Health Inventory for Men

- WHO:

-

World health organisation

References

The Prevalence and Types of Sexual Dysfunction in People With Cancer | HealthCentral n.d. https://www.healthcentral.com/article/the-prevalence-and-types-of-sexual-dysfunction-in-people-with-cancer (Accessed 11 Aug 2019).

Laumann EO, Paik A, Rosen RC. Sexual dysfunction in the United States. JAMA. 1999;281:537. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.281.6.537.

Levin RJ. Critically revisiting aspects of the human sexual response cycle of masters and Johnson: correcting errors and suggesting modifications. Sex Relatsh Ther. 2008;23:393–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681990802488816.

WHO | Sexual health. WHO 2016.

Wettergren L, Kent EE, Mitchell SA, Zebrack B, Lynch CF, Rubenstein MB, et al. Cancer negatively impacts on sexual function in adolescents and young adults: the AYA HOPE study. Psychooncology. 2017;26:1632–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4181.

Basson R, Rees P, Wang R, Montejo AL, Incrocci L. Sexual function in chronic illness. J Sex Med. 2010;7:374–88. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01621.x.

Bhanvadia SK. Bladder Cancer survivorship. Curr Urol Rep. 2018;19:111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11934-018-0860-6.

Mohamed NE, Chaoprang Herrera P, Hudson S, Revenson TA, Lee CT, Quale DZ, et al. Muscle invasive bladder cancer: examining survivor burden and unmet needs. J Urol. 2014;191:48–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2013.07.062.

Paterson C, Jensen BT, Jensen JB, Nabi G. Unmet informational and supportive care needs of patients with muscle invasive bladder cancer: a systematic review of the evidence. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2018;35:92–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EJON.2018.05.006.

Isharwal S, Konety B. Non-muscle invasive bladder cancer risk stratification. Indian J Urol. 2015;31:289–96. https://doi.org/10.4103/0970-1591.166445.

Jeong CW. Quality of Life in Bladder Cancer Patients. Bl. Cancer, Elsevier; 2018. p. 507–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-809939-1.00028-X.

Bladder cancer: diagnosis and Bladder cancer: diagnosis and management management NICE guideline. 2015.

Pederzoli F, Campbell JD, Matsui H, Sopko NA, Bivalacqua TJ. Surgical factors associated with male and female sexual dysfunction after radical cystectomy: what do we know and how can we improve outcomes? Sex Med Rev. 2018;6:469–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sxmr.2017.11.003.

EAU Guidelines | Uroweb n.d. https://uroweb.org/guidelines/ (Accessed 11 Aug 2019).

Moeen AM, Safwat AS, Gadelmoula MM, Moeen SM, Abonnoor AEI, Abbas WM, et al. Health related quality of life after urinary diversion. Which technique is better? J Egypt Natl Canc Inst. 2018;30:93–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnci.2018.08.001.

Bladder Cancer & Sexual Health | BladderCancer.net n.d. https://bladdercancer.net/living/sexual-health/ (Accessed 22 Sept 2019).

Sex life | Bladder cancer | Cancer Research UK n.d. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/bladder-cancer/living-with/sex-life (Accessed 22 Sept 2019).

Kandemir D, Oskay Ü. Sexual problems of patients with Urostomy: a qualitative study. Sex Disabil. 2017;35:331–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-017-9494-8.

Bolat D, Celik S, Aydin ME, Aydogdu O, Gunlusoy B, Degirmenci T, et al. Assessment of the quality of life and sexual functions of patients followed-up for non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: preliminary results of the prospective-descriptive study. Türk Üroloji Dergisi/Turkish J Urol. 2018;44:393–8. https://doi.org/10.5152/tud.2018.30040.

Mak KS, Smith AB, Eidelman A, Clayman R, Niemierko A, Cheng J-S, et al. Quality of life in long-term survivors of muscle-invasive bladder Cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol. 2016;96:1028–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IJROBP.2016.08.023.

Mohamed NE, Pisipati S, Lee CT, Goltz HH, Latini DM, Gilbert FS, et al. Unmet informational and supportive care needs of patients following cystectomy for bladder cancer based on age, sex, and treatment choices. Urol Oncol Semin Orig Investig. 2016;34:531.e7–531.e14. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.UROLONC.2016.06.010.

Booth BB, Rasmussen A, Jensen JB. Evaluating sexual function in women after radical cystectomy as treatment for bladder cancer. Scand J Urol. 2015;49:463–7. https://doi.org/10.3109/21681805.2015.1055589.

Goossens-Laan CA, PJM K, JLHR B, De Vries J. Patient-reported outcomes for patients undergoing radical cystectomy: a prospective case-control study. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22:189–200. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-013-1946-9.

Allareddy V, Kennedy J, West MM, Konety BR. Quality of life in long-term survivors of bladder cancer. Cancer. 2006;106:2355–62. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.21896.

Forbes MK, Baillie AJ, Schniering CA. Critical flaws in the female sexual function index and the international index of erectile function. J Sex Res. 2014;51:485–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2013.876607.

Modh RA, Mulhall JP, Gilbert SM. Sexual dysfunction after cystectomy and urinary diversion. Nat Rev Urol. 2014;11:445–53. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrurol.2014.151.

Selby P, Velikova G. Taking patient reported outcomes Centre stage in cancer research – why has it taken so long? Res Involv Engagem. 2018;4:25. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40900-018-0109-z.

Oberguggenberger AS, Nagele E, Inwald EC, Tomaszewski K, Lanceley A, Nordin A, et al. Phase 1-3 of the cross-cultural development of an EORTC questionnaire for the assessment of sexual health in cancer patients: the EORTC SHQ-22. Cancer Med. 2018;7:635–45. https://doi.org/10.1002/cam4.1338.

Litwin MS, McGuigan KA. Accuracy of recall in health-related quality-of-life assessment among men treated for prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2882–8. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.1999.17.9.2882.

Litwin MS, Hays RD, Fink A, Ganz PA, Leake B, Leach GE, et al. Quality-of-life outcomes in men treated for localized prostate cancer. JAMA. 1995;273:129–35. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.273.2.129.

Yoshimura K, Utsunomiya N, Ichioka K, Matsui Y, Terai A, Arai Y. Impact of superficial bladder cancer and transurethral resection on general health-related quality of life: an SF-36 survey. Urology. 2005;65:290–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2004.09.050.

Månsson A, Johnson G, Månsson W. Psychosocial adjustment to cystectomy for bladder carcinoma and effects on interpersonal relationships. Scand J Caring Sci. 1991;5:129–34.

Protogerou V, Moschou M, Antoniou N, Varkarakis J, Bamias A, Deliveliotis C. Modified S-pouch neobladder vs ileal conduit and a matched control population: a quality-of-life survey. BJU Int. 2004;94:350–4. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-410X.2004.04932.x.

Jacobs BL, Daignault S, Lee CT, Hafez KS, Montgomery JS, Montie JE, et al. Prostate capsule sparing versus nerve sparing radical cystectomy for bladder Cancer: results of a randomized, controlled trial. J Urol. 2015;193:64–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JURO.2014.07.090.

Moeen AM, Safwat AS, Gadelmoula MM, Moeen SM, Abonnoor AEI, Abbas WM, et al. Health related quality of life after urinary diversion. Which technique is better? J Egypt Natl Canc Inst. 2018;30:93–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JNCI.2018.08.001.

Voskuilen CS, Fransen van de Putte EE, Pérez-Reggeti JI, van Werkhoven E, Mertens LS, van Rhijn BWG, et al. Prostate sparing cystectomy for bladder cancer: a two-center study. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2018;44:1446–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2018.05.032.

Chen PY, Chiang PH. Comparisons of quality of life and functional and oncological outcomes after Orthotopic Neobladder reconstruction: prostate-sparing cystectomy versus conventional radical Cystoprostatectomy. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/1983428.

Kanashiro A, Gaya JM, Palou J, Gausa L, Villavicencio H. Robot-assisted radical cystoprostatectomy: Analysis of the complications and oncological and functional aspects. Actas Urológicas Españolas. 2017;41:267–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acuroe.2017.03.006.

Wishahi M, Elganozoury H. Survival up to 5-15 years in young women following genital sparing radical cystectomy and neobladder: oncological outcome and quality of life. Single-surgeon and single-institution experience. Cent Eur J Urol. 2015;68:141–5. https://doi.org/10.5173/ceju.2015.475.

Kowalkowski MA, Chandrashekar A, Amiel GE, Lerner SP, Wittmann DA, Latini DM, et al. Examining sexual dysfunction in non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer: results of cross-sectional mixed-methods research. Sex Med. 2014;2:141–51. https://doi.org/10.1002/sm2.24.

Ali-El-Dein B, Mosbah A, Osman Y, El-Tabey N, Abdel-latif M, Eraky I, et al. Preservation of the internal genital organs during radical cystectomy in selected women with bladder cancer: a report on 15 cases with long term follow-up. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2013;39:358–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EJSO.2013.02.004.

Takenaka A, Hara I, Soga H, Sakai I, Terakawa T, Muramaki M, et al. Assessment of long-term quality of life in patients with orthotopic neobladder followed for more than 5 years. Int Urol Nephrol. 2011;43:749–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11255-010-9851-3.

Salem HK. Radical cystectomy with preservation of sexual function and fertility in patients with transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder: new technique. Int J Urol. 2007;14:294–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-2042.2007.01607.x.

Salem HK. Preservation of ejaculatory and erectile function after radical cystectomy for urothelial malignancy. J Egypt Natl Canc Inst. 2005;17:239–44.

Lane BR, Finelli A, Moinzadeh A, Sharp DS, Ukimura O, Kaouk JH, et al. Nerve-sparing laparoscopic radical cystectomy: technique and initial outcomes. Urology. 2006;68:778–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2006.05.027.

Nandipati KC, Bhat A, Zippe CD. Neurovascular preservation in female orthotopic radical cystectomy significantly improves sexual function. Urology. 2006;67:185–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.UROLOGY.2005.07.024.

Bhatt A, Nandipati K, Dhar N, Ulchaker J, Jones S, Rackley R, et al. Neurovascular preservation in orthotopic cystectomy: impact on female sexual function. Urology. 2006;67:742–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2005.10.015.

Volkmer BG, Gschwend JE, Herkommer K, Simon J, Küfer R, Hautmann RE. Cystectomy and orthotopic ileal neobladder: the impact on female sexuality. J Urol. 2004;172:2353–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ju.0000145190.84531.66.

Zippe CD, Raina R, Massanyi EZ, Agarwal A, Jones JS, Ulchaker J, et al. Sexual function after male radical cystectomy in a sexually active population. Urology. 2004;64:682–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2004.05.056.

Terrone C, Cracco C, Scarpa RM, Rossetti SR. Supra-ampullar cystectomy with preservation of sexual function and ileal orthotopic reservoir for bladder tumor: twenty years of experience. Eur Urol. 2004;46:264–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2004.03.006.

Zippe CD, Raina R, Shah AD, Massanyi EZ, Agarwal A, Ulchaker J, et al. Female sexual dysfunction after radical cystectomy: a new outcome measure. Urology. 2004;63:1153–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2003.12.034.

Miyao N, Adachi H, Sato Y, Horita H, Takahashi A, Masumori N, et al. Recovery of sexual function after nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy or cystectomy. Int J Urol. 2001;8:158–64. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1442-2042.2001.00274.x.

Little FA, Howard GCW. Sexual function following radical radiotherapy for bladder cancer. Radiother Oncol. 1998;49:157–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-8140(98)00109-1.

Schover LR, Evans R, Von Eschenbach AC. Sexual rehabilitation and male radical cystectomy. J Urol. 1986;136:1015–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-5347(17)45192-5.

Schove LR, Von Eschenbach AC. Sexual function and female radical cystectomy: a case series. J Urol. 2017;134:465–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-5347(17)47242-9.

El-Bahnasawy MS, Osman Y, El-Hefnawy A, Hafez A, Abdel-Latif M, Mosbah A, et al. Radical cystectomy and urinary diversion in women: impact on sexual function. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2011;45:332–8. https://doi.org/10.3109/00365599.2011.585621.

Bjerre BD, Joh C. Sexological problems after cystectomy: bladder substitution compared with Ileal conduit diversion: a questionnaire study of male patients. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1998;32:187–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/003655998750015557.

Tomić R, Sjödin JG. Sexual function in men after radical cystectomy with or without urethrectomy. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1992;26:127–9.

Moursy EES, Eldahshoursy MZ, Gamal WM, Badawy AA. Orthotopic genital sparing radical cystectomy in pre-menopausal women with muscle-invasive bladder carcinoma: a prospective study. Indian J Urol. 2016;32:65–70. https://doi.org/10.4103/0970-1591.173112.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Action Bladder Cancer UK and Arcobaleno Cancer Trust.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

all authors have read and approved the manuscript. Conception and design: AB, RM, MVH. Acquisition of data: AB, RM. Analysis and interpretation of data: AB, RM, MVH. Drafting of the manuscript: AB. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: CH, DE, SA, MK, FC, HW, SB, KC, SM, RN, PK, AH, SG, MN, KB, RT, MVH.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

PROTOCOL: Systematic literature review on sexual health for patients with bladder cancer.

AIM: To consolidate an overview of studies that address sexual health in bladder cancer patients

Objectives

-

Assess the methodology used to evaluate sexual health in terms of coverage and validation after bladder cancer treatment,

-

Understand the role of bladder cancer treatment and psychosocial factors of sexual functioning

METHODS

Reports of current systematic review protocol adhere to the Preferred Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis Protocol (PRISMA-P) checklist. The systematic review itself will adhere to the PRISMA.

Criteria for considering studies for this review.

Types of studies.

Any study that investigated sexual function or sexual dysfunction; any study where sexual function/sexual dysfunction/sexual health were measured by self-reports or an interview. Studies were original full text report in English and were published in peer-reviewed journals.

Types of participants.

The population of interest will be bladder cancer patients. Demographic factors are no exclusion criteria except for age (< 18 years of age).

Types of outcomes measures.

For both primary and secondary outcome measures, there will be no exclusion based on length of follow-up.

Primary outcomes.

Sexual function or sexual dysfunction in bladder cancer patients.

Secondary outcomes.

Treatment and psychosocial factors of sexual functioning.

SEARCH METHODS FOR IDENTIFICATION OF STUDIES.

Electronic searches.

The following electronic databases will be searched from inception until the search date: the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE (using the PubMed interface), Embase (using the embase.com interface) and PsychINFO.

Data collection and analysis.

Selection of studies.

All references found through the search process will be downloaded in a database created by reference management software (Endnote). After removing duplicates in Endnote, all references will be imported into Covidence for screening purposes. Obviously irrelevant studies, based on title and abstract, will independently be excluded by two review authors. After screening the titles and abstracts, two review authors will independently assess full-text reports for eligibility. Discrepancies will be discussed with a third review author. Reasons for exclusion of full-texts will be documented. Studies will be excluded if no full-text is available. Abstracts in any other language than English will be excluded. There will be no language restriction for full texts, and translations will be carried out if necessary. If studies have multiple publications with the same outcome(s) reported, manuscripts with the longest follow-up will be selected for inclusion.

Data extraction.

For each included study in the review, at least the following information will be extracted:

- General information: report title, report ID, authors’ names, country, contact address, language of publication and year of publication.

- Population and setting: population description (from which study participants are drawn), setting when applicable (eg, inpatient, outpatient, hospital setting, home setting and combination) and inclusion and exclusion criteria.

- Methods: aim of study, design, start and end date and duration of participation.

- Participants: number of participants, received treatment.

- Outcomes: outcome name, time points measured and reported.

- Results: measurement of sexual function and sexual dysfunction, psychosocial factors measured.

Dealing with missing data.

If essential data are not available in the publication, we will first attempt to contact the study authors. If this is not possible, we will try to back-calculate from the data presented. If data will be obtained from other study authors, this will be reported in the review in a transparent manner. This way, we can keep in mind that these missing data obtained from study authors were not peer reviewed. Studies assessing lifestyle interventions may have issues with compliance. Therefore, reasons for missing data (eg, dropouts, losses to follow-up and withdrawals) will be carefully reported.

Data synthesis.

The findings from the included studies will be summarised in a table format.

ETHICS AND DISSEMINATION.

Ethics approval is not required, as no primary data will be collected. Results will be disseminated through a peer-reviewed publication.

The results of this systematic review could also have potential limitations in terms of biased results due to the nature of the patient reported outcomes.

Appendix 2

Search strategy

PubMed.

“Urinary Bladder Neoplasms”[MESH] OR “Urinary Bladder/abnormalities”[MESH] OR “Urinary bladder/surgery”[MESH] OR “Carcinoma, Transitional Cell”[Mesh] OR “bladder cancer”[TIAB] OR “bladder cancers”[TIAB] OR “bladder carcinoma”[TIAB] OR “bladder carcinomas”[TIAB] OR “bladder malignancy”[TIAB] OR “bladder malignancies”[TIAB] OR “bladder neoplasm”[TIAB] OR “bladder neoplasms”[TIAB] OR “bladder tumor”[TIAB] OR “bladder tumors”[TIAB] OR “bladder tumour”[TIAB] OR “bladder tumours”[TIAB] OR “transitional cell carcinoma”[TIAB] OR “transitional cell carcinomas”[TIAB] OR “transitional cell cancer”[TIAB] OR “transitional cell cancers”[TIAB] OR “transitional cell malignancies”[TIAB] OR “transitional cell tumor”[TIAB] OR “transitional cell tumors”[TIAB] OR “transitional cell tumour”[TIAB] OR “transitional cell tumours”[TIAB]

And

“Sexual function” OR “sexual dysfunction” OR “wellbeing” OR “intimacy” OR “sexuality” OR “sexual physiology” OR “sexual physiopathology” “sexual heath”

And

“Cystectomy” OR “radical cystectomy” OR “partial cystectomy” OR “TURBT” OR “Transurethral resection of bladder tumour” OR “BCG” OR “chemotherapy” OR “Radiotherapy” OR “Bacillus Calmette–Guérin vaccine”.

Cochrane Library.

“Urinary Bladder Neoplasms” OR “Urinary Bladder abnormalities” OR “Urinary bladder surgery” OR “Carcinoma, Transitional Cell” OR “bladder cancer” OR “bladder cancers” OR “bladder carcinoma” OR “bladder carcinomas” OR “bladder malignancy” OR “bladder malignancies” OR “bladder neoplasm” OR “bladder neoplasms” OR “bladder tumor” OR “bladder tumors” OR “bladder tumour” OR “bladder tumours” OR “transitional cell carcinoma” OR “transitional cell carcinomas” OR “transitional cell cancer” OR “transitional cell cancers” OR “transitional cell malignancies” OR “transitional cell tumor” OR “transitional cell tumors” OR “transitional cell tumour” OR “transitional cell tumours”

And

“Sexual function” OR “sexual dysfunction” OR “wellbeing” OR “intimacy” OR “sexuality” OR “sexual physiology” OR “sexual physiopathology”

And

“Cystectomy” OR “radical cystectomy” OR “partial cystectomy” OR “TURBT” OR “Transurethral resection of bladder tumour” OR “BCG” OR “chemotherapy” OR “Radiotherapy” OR “Bacillus Calmette–Guérin vaccine”.

Embase.

Urinary Bladder Neoplasms OR Urinary Bladder abnormalities OR Urinary bladder surgery OR Carcinoma, Transitional Cell OR bladder cancer OR bladder cancers OR bladder carcinoma OR bladder carcinomas OR bladder malignancy OR bladder malignancies OR bladder neoplasm OR bladder neoplasms OR bladder tumor OR bladder tumors OR bladder tumour OR bladder tumours OR transitional cell carcinoma OR transitional cell carcinomas OR transitional cell cancer OR transitional cell cancers OR transitional cell malignancies OR transitional cell tumor OR transitional cell tumors OR transitional cell tumour OR transitional cell tumours

And

Sexual function OR sexual dysfunction OR sexual health OR wellbeing OR intimacy OR sexuality OR sexual physiology OR sexual physiopathology

And

Cystectomy OR radical cystectomy OR partial cystectomy OR TURBT OR Transurethral resection of bladder tumour OR BCG OR chemotherapy OR Radiotherapy OR Bacillus Calmette Guerin vaccine OR Intravesical therapy OR Systemic immunotherapy.

Appendix 3

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Bessa, A., Martin, R., Häggström, C. et al. Unmet needs in sexual health in bladder cancer patients: a systematic review of the evidence. BMC Urol 20, 64 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12894-020-00634-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12894-020-00634-1