Abstract

Purpose

Recent controversial publications, citing studies purporting to show that P-gp mediates the transport of propranolol, proposed that passive biological membrane transport is negligible. Based on the BDDCS, the extensively metabolized-highly permeable-highly soluble BDDCS class 1 drug, propranolol, shows a high passive permeability at concentrations unrestricted by solubility that can overwhelm any potential transporter effects. Here we reinvestigate the effects of passive diffusion and carrier-mediated transport on S-propranolol.

Methods

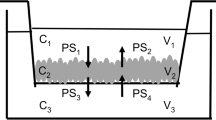

Bidirectional permeability and inhibition of efflux transport studies were carried out in MDCK, MDCK-MDR1 and Caco-2 cell lines at different concentrations. Transcellular permeability studies were conducted at different apical pHs in the rat jejunum Ussing chamber model and PAMPA system.

Results

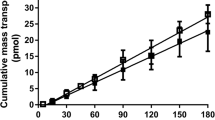

S-propranolol exhibited efflux ratios lower than 1 in MDCK, MDCK-MDR1 and Caco-2 cells. No significant differences of Papp, B->A in the presence and absence of the efflux inhibitor GG918 were observed. However, an efflux ratio of 3.63 was found at apical pH 6.5 with significant decrease in Papp, A->B and increase in Papp, B->A compared to apical pH 7.4 in Caco-2 cell lines. The pH dependent permeability was confirmed in the Ussing chamber model. S-propranolol flux was unchanged during inhibition by verapamil and rifampin. Furthermore, pH dependent permeability was also observed in the PAMPA system.

Conclusions

S-propranolol does not exhibit active transport as proposed previously. The “false” positive efflux ratio can be explained by the pH partition theory. As expected, passive diffusion, but not active transport, plays the primary role in the permeability of the BDDCS class 1 drug propranolol.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- ASBT:

-

Apical sodium/bile acid co-transporter

- BCRP:

-

Breast cancer resistance protein

- BDDCS:

-

Biopharmaceutics drug disposition classification system

- FBS:

-

Fetal bovine serum

- GG918(GF120918):

-

N-{4-[2-(1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-6,7-dimethoxy-2-isoquinolinyl)-ethyl]-phenyl}-9,10-dihydro-5-methoxy-9-oxo-4-acridinecarboxamide

- HBSS:

-

Hank’s balanced salt solution

- MCT:

-

Monocarboxylic acid transporter

- MDCK:

-

Madin-Darby canine kidney

- MRP:

-

multidrug resistance like protein

- OATP:

-

Organic anion transporting polypeptide

- OCT:

-

Organic cation transporter

- PAMPA:

-

Parallel artificial membrane permeability assay

- Papp :

-

Apparent permeability coefficient

- Papp A->B :

-

Apical-to-basolateral Papp

- Papp B->A :

-

Basolateral-to-apical Papp

- PEPT:

-

Proton-coupled oligopeptide transporter

- P-gp (MDR1):

-

P-glycoprotein

- TEER:

-

Transepithelial electrical resistance

References

Kell DB, Dobson PD, Oliver SG. Pharmaceutical drug transport: the issues and the implications that it is essentially carrier-mediated only. Drug Discov Today. 2011;16(15–16):704–14.

Kell DB, Dobson PD, Bilsland E, Oliver SG. The promiscuous binding of pharmaceutical drugs and their transporter-mediated uptake into cells: what we (need to) know and how we can do so. Drug Discov Today. 2013;18(5–6):218–39.

Sugano K, Kansy M, Artursson P, Avdeef A, Bendels S, Di L, et al. Coexistence of passive and carrier-mediated processes in drug transport. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9(8):597–614.

Di L, Artursson P, Avdeef A, Ecker GF, Faller B, Fischer H, et al. Evidence-based approach to assess passive diffusion and carrier-mediated drug transport. Drug Discov Today. 2012;17(15–16):905–12.

Wu CY, Benet LZ. Predicting drug disposition via application of BCS: transport/absorption/ elimination interplay and development of a biopharmaceutics drug disposition classification system. Pharm Res. 2005;22(1):11–23.

Custodio JM, Wu CY, Benet LZ. Predicting drug disposition, absorption/elimination/transporter interplay and the role of food on drug absorption. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2008;60(6):717–33.

Barrett AM, Cullum VA. The biological properties of the optical isomers of propranolol and their effects on cardiac arrhythmias. Br J Pharmacol. 1968;34(1):43–55.

Stoschitzky K, Lindner W, Rath M, Leitner C, Uray G, Zernig G, et al. Stereoselective hemodynamic effects of (R)-and (S)-propranolol in man. Naunyn Schmiedeberg’s Arch Pharmacol. 1989;339(4):474–8.

Lennernas H, Nylander S, Ungell AL. Jejunal permeability: a comparison between the ussing chamber technique and the single-pass perfusion in humans. Pharm Res. 1997;14(5):667–71.

Yang JJ, Kim KJ, Lee VH. Role of P-glycoprotein in restricting propranolol transport in cultured rabbit conjunctival epithelial cell layers. Pharm Res. 2000;17(5):533–8.

Wang Y, Cao J, Wang X, Zeng S. Stereoselective transport and uptake of propranolol across human intestinal Caco-2 cell monolayers. Chirality. 2010;22(3):361–8.

D’Emanuele A, Jevprasesphant R, Penny J, Attwood D. The use of a dendrimer-propranolol prodrug to bypass efflux transporters and enhance oral bioavailability. J Controll Release. 2004;95(3):447–53.

Benet LZ, Broccatelli F, Oprea TI. BDDCS applied to over 900 drugs. AAPS J. 2011;13(4):519–47.

Nishimura T, Kato Y, Amano N, Ono M, Kubo Y, Kimura Y, et al. Species difference in intestinal absorption mechanism of etoposide and digoxin between cynomolgus monkey and rat. Pharm Res. 2008;25(11):2467–76.

Liu W, Okochi H, Benet LZ, Zhai SD. Sotalol permeability in cultured-cell, rat intestine, and PAMPA system. Pharm Res. 2012;29(7):1768–74.

Kell DB, Oliver SG. How drugs get into cells: tested and testable predictions to help discriminate between transporter-mediated uptake and lipoidal bilayer diffusion. Front Pharmacol. 2014;5:231. doi:10.3389/fphar.2014.00231.

Dobson PD, Kell DB. Carrier-mediated cellular uptake of pharmaceutical drugs: an exception or the rule? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7(3):205–20.

Dobson PD, Lanthaler K, Oliver SG, Kell DB. Implications of the dominant role of transporters in drug uptake by cells. Curr Top Med Chem. 2009;9(2):163–81.

Benet LZ. The role of BCS (biopharmaceutics classification system) and BDDCS (biopharmaceutics drug disposition classification system) in drug development. J Pharm Sci. 2013;102(1):34–42.

Kubo Y, Kusagawa Y, Tachikawa M, Akanuma S, Hosoya K. Involvement of a novel organic cation transporter in verapamil transport across the inner blood-retinal barrier. Pharm Res. 2013;30(3):847–56.

Kubo Y, Shimizu Y, Kusagawa Y, Akanuma S, Hosoya K. Propranolol transport across the inner blood-retinal barrier: potential involvement of a novel organic cation transporter. J Pharm Sci. 2013;102(9):3332–42.

Dudley AJ, Bleasby K, Brown CD. The organic cation transporter OCT2 mediates the uptake of beta-adrenoceptor antagonists across the apical membrane of renal LLC-PK(1) cell monolayers. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;131(1):71–9.

Zheng XL, Yu QQ, Wang Y, Zeng S. Stereoselective accumulation of propranolol enantiomers in K562 and K562/ADR cells. Chirality. 2013;25(6):361–4.

International Transporter C, Giacomini KM, Huang SM, Tweedie DJ, Benet LZ, Brouwer KL, et al. Membrane transporters in drug development. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9(3):215–36.

Zhou SF, Wang LL, Di YM, Xue CC, Duan W, Li CG, et al. Substrates and inhibitors of human multidrug resistance associated proteins and the implications in drug development. Curr Med Chem. 2008;15(20):1981–2039.

Smith DE, Clemencon B, Hediger MA. Proton-coupled oligopeptide transporter family SLC15: physiological, pharmacological and pathological implications. Mol Asp Med. 2013;34(2–3):323–36.

Halestrap AP. Monocarboxylic acid transport. J Comp Physiol. 2013;3(4):1611–43.

Ma L, Juttner M, Kullak-Ublick GA, Eloranta JJ. Regulation of the gene encoding the intestinal bile acid transporter ASBT by the caudal-type homeobox proteins CDX1 and CDX2. Am J Physiol Gastr Liver Physiol. 2012;302(1):G123–33.

Stephens RH, Tanianis-Hughes J, Higgs NB, Humphrey M, Warhurst G. Region-dependent modulation of intestinal permeability by drug efflux transporters: in vitro studies in mdr1a(-/-) mouse intestine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;303(3):1095–101.

Neuhoff S, Ungell AL, Zamora I, Artursson P. pH-dependent bidirectional transport of weakly basic drugs across Caco-2 monolayers: implications for drug-drug interactions. Pharm Res. 2003;20(8):1141–8.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS AND DISCLOSURES

We thank the Chinese Scholarship Council for providing financial support for Yi Zheng to study and carry out these studies in Dr. Benet’s laboratory at the University of California, San Francisco. The studies in Dr. Benet’s lab were funded in part by NIH grants RR031474 and GM061390.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zheng, Y., Benet, L.Z., Okochi, H. et al. pH Dependent but not P-gp Dependent Bidirectional Transport Study of S-propranolol: The Importance of Passive Diffusion. Pharm Res 32, 2516–2526 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11095-015-1640-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11095-015-1640-3