Abstract

Middle voice verbs contrast with transitive active verbs in showing detransitivization. However, they also constitute a heterogeneous set syntactically and semantically, including anticausative, dispositional, inherent reflexive, and passive readings, with a syntax that seems more unergative or unaccusative depending on the reading and the language. Thus the category has defied attempts at a unified formal definition, leading some to suggest it is a family of constructions or a notional category. We present data on ber- middles in Indonesian and their allomorphs, which show all of the canonical types of middle voice readings but also several additional types not attested in other languages. These include some in which both of the corresponding active forms’ arguments are expressed as direct arguments, where the subject of the active corresponds to the subject of the middle and the object is incorporated. Although this may seem to add additional reason to support a family of constructions analysis, we show that a single unified definition is possible. We propose that ber- suppresses one argument of the verb, but it is unspecified as to which is suppressed. Different independent argument realization possibilities of Indonesian conspire to sometimes suppress the subject and sometimes the object. Coupled with principles of implicit argument interpretation and lexical semantic and pragmatic factors, all of the middle readings of Indonesian arise from this one operation. Middles in other languages may in turn follow from the same analysis, but some of the available options may not arise owing to typological aspects of those languages, and a family of constructions analysis may even be necessary in those cases. Thus a syntactically and semantically unified analysis of middles is possible, albeit manifesting in different ways in different languages.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

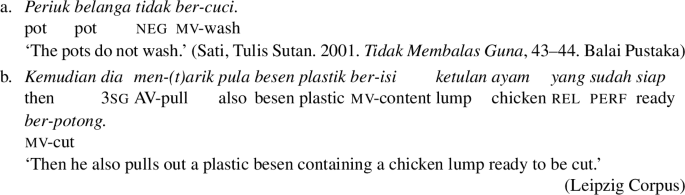

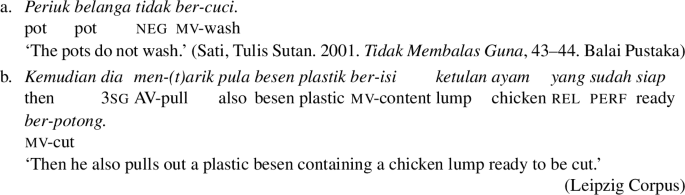

The glosses below follow the Leipzig Glossing Conventions, plus the following abbreviations: av = agent (active) voice, emph = emphatic, inv = involitive mood, mv = middle voice, npst = non-past tense, ov = object (active) voice, post = postpositional case, prt = participle, vol = volitive mood.

We employ the terms “unaccusative” and “unergative” here in a descriptive way for verbs taking a subject DP that is either the root’s underlying object (“unaccusative”) or its underlying subject (“unergative”). We remain neutral as to how to define those grammatical functions and how object-to-subject promotion is implemented, though for purposes of outlining a concrete formal analysis we adopt a raising analysis.

Alternatively, middles formed with pronominals/clitics as in (1) might be transitive, with the pronominal/clitic se filling an argument position as per Schäfer (2017) on Romance (see also Doron and Rappaport Hovav 2009; Sportiche 2014; Alexiadou et al. 2015: 110–114; inter alia). This is contra treating se as a verbal head/modifier à la Labelle (2008) or Koontz-Garboden (2009), inter alia (see also Alexiadou and Schäfer 2014 and Alexiadou et al. 2015: 103–107 on German reflexives, and Beavers and Zubair 2016: 98–103 on Sinhala dispositional/reflexive middles). Even here though it is non-obvious whether the surface DP is the base subject or object; Schäfer suggests it can be both. Our study focuses on middles formed via head-marking without pronominals, but we return to transitive analyses in Sect. 2.5 and Sect. 7.1.

The N in meN- represents a final nasal consonant that shows place assimilation with the first segment of the verbal root it attaches to; see Sneddon (1996: 9). Indonesian generally does not indicate tense; the tenses in the translations here and below are what are deemed the most natural interpretations in English.

These are more common in Malay than Indonesian and speakers vary on their acceptability, though some Indonesian speakers we have consulted do accept them, and naturally attested examples can be found:

-

(i)

Again, our goal is to explain their properties when they do arise for a speaker rather than when they will arise.

-

(i)

Example (10c) might be acceptable on reading where only the car had properties allowing the causer to sell it (following on the responsibility meaning mentioned above). However, this is not the intended reading.

To illustrate the range of (im)possible control relations between surface DPs and PRO, and to ensure inanimacy is not responsible for the inability of a DP to control PRO, we use human subject and object DPs since these can in principle readily be agents, though this requires somewhat unusual examples.

The unacceptability of rationale clauses here holds regardless of whether the reading is more like a dispositional or a passive, modulo the caveat about pragmatic controllers.

As noted in Sect. 1, middles can have reciprocal readings, true also in Indonesian (e.g. ber-tengkar mv-fight, ‘fight with each other’) (Sneddon 1996: 109–110; Ogloblin and Nedjalkov 2007; Udayana 2017). Circumfix ber- -an forms reciprocals productively, though our focus is on simple ber- forms (which Ogloblin and Nedjalkov 2007: 1455 suggest are lexicalized). For now we assume reciprocals can be assimilated to reflexives as a special type for plural subjects (see e.g. Haug and Dalrymple 2019: 9), and do not address them distinctly.

As a reviewer notes, ber-dandan also has a conventional usage meaning ‘be adorned (with clothes, jewelry, etc.)’ Of course, an event of the sort described by reflexive or passive ber-dandan must have occurred to become so adorned. So it is not clear this is a separate usage. But if so, it is not unexpected that it could arise since it would be a natural pathway of lexical drift through for a term to develop a stative sense reflecting the target state of the event in the sense of Kratzer (2000: 386). See Beavers and Koontz-Garboden (2020: 72–73) for discussion of lexical drift resulting in loss of eventive entailments for English closed and broken.

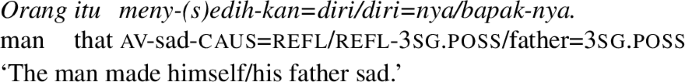

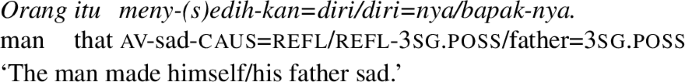

There is another reflexive middle that has a seemingly adjectival base, including those that describe emotional states such as ber-sedih, mv-sad ‘sadden oneself’ from sedih ‘sad.’ It is mysterious if these are derived from intransitive adjectives rather than transitive verbs. However, for some speakers these ber- forms have the same meaning as the corresponding meN- -kan when such forms occur with a reflexive object:

-

(i)

That the meaning of the ber- form is causative suggests it is derived from the meN- -kan verb and not the adjective (and is interpreted as reflexive for whatever reason), thus assimilatable with natural reflexives. That said, for some speakers ber-sedih can have a purely stative reading. However, as a reviewer notes these could reflect a ber- form with a non-verbal base deriving a possessional ‘have sadness’ stative reading as in Sect. 4 (see e.g. Francez and Koontz-Garboden 2017), or it could arise through lexical drift as per fn. 10. Finally, there are a few ber- forms with reduplicated adjective bases that lack meN- variants, including bersenang∼senang ‘enjoy oneself’ (from senang ‘happy’), and bermalas∼malas ‘loaf oneself around’ (from malas ‘lazy’), suggesting these may be deponents (see Sect. 6). We leave these for future research.

-

(i)

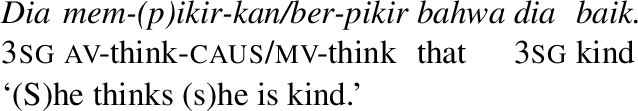

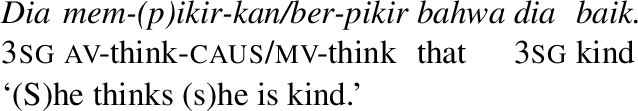

There is another ber- middle whose subject is the underlying subject, namely cognition middles as with verbs like mem-(p)ikir-kan/ber-pikir, av-think-cuas/mv-think ‘think,’ where the complement is a clause rather than an NP (see e.g. Jeoung 2018: 62–63):

-

(i)

Our focus is on verbs with noun phrase complements, but as we note in fn. 24 an extension of our analysis of incorporated object middles can extend to these.

-

(i)

A reviewer notes that some antipassives show incorporation, as shown by Baker (1988: 130–146) and discussed more recently by Polinsky (2017: 312–314), who also notes that antipassive morphemes can sometimes be syncretic with middle, reflexive, and passive marking. Indonesian has no regular antipassive (Aldridge 2011: 343), though the correlation between incorporation middles and antipassives more broadly is an interesting one. However, it would take us too far afield and thus we leave it for further research.

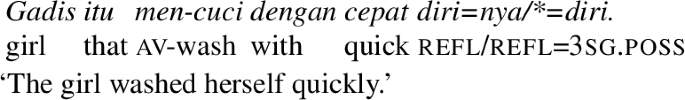

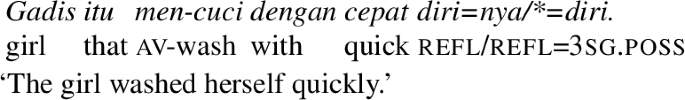

Diri is homophonous with (and historically derived from) the noun diri ‘body.’ Short diri reflexives are also semantically distinguished from long reflexives in being restricted to only refer to patients (see Udayana 1994). As noted above, simple reflexive diri is possible with the meN- form, though it is again non-separable:

-

(i)

As far as we are aware, meN- forms do not allow lexical NP incorporation; we thus treat this non-separable use of diri with meN- forms as a separate operation that we do not discuss further here.

-

(i)

A syntactic analysis of incorporation and voice is not necessary. A lexical sharing analysis of incorporation à la Wescoat (2002) or Ball (2005)—wherein V and N are compounded in the lexicon and the resulting category has properties of both—is possible. This could be coupled with a treatment of voice as lexical inflection sensitive to compounding that constrains a separate verbal argument structure (as in Pollard and Sag 1994, Ginzburg and Sag 2000). Our claims do not hinge on the formal implementation so much as the idea that ber- shows variable detransitivization properties that interact with incorporation.

Alternatively, in the spirit of Jaeggli (1986: 590–599) we could say di- somehow syntactically represents the argument by bearing the relevant index and ϕ-features, assuming there is no null subject. The details of the analysis of passives ultimately do not matter here (see also Sect. 7.1). See Alexiadou et al. (2015: 123–143) for an excellent summary of the debate about implicit syntactic arguments in passives.

As Alexiadou et al. (2015: 141–142) note, the assumption of a syntactic weak implicit argument might derive the disjoint reference effect depending on its properties (see also Landau 2010: 376–377); we do not decide the issue, but instead assume both the weak implicit argument and an explicit disjoint reference effect.

Anticausatives also differ from causatives in being realized in involitive mood rather than the volitive. The interaction of anticausativization with (in)volitive mood plays a significant role in the argumentation of Beavers and Zubair (2013), but the details are irrelevant here and thus we ignore it. See also Beavers and Zubair (2016) for an extension of this analysis to other middles in Sinhala, briefly discussed in Sect. 7.

While Causer Suppression is a pre-syntactic operation over verbal roots, we analyze ber- as a v head over VPs. A lexicalist variant of our analysis of ber- as per fn. 15 would simply saturate the V’s second argument.

The role of lexical information constraining interpretation by default may in turn just be an outgrowth of the pragmatic Principle of Interpretive Economy of Kennedy (2007: 36, (66)) (“Maximize the contribution of the conventional meanings of the elements of a sentence to the computation of its truth conditions”), which Kennedy uses to explain how the lexical semantics and conventional usages of scalar adjectives figure into how they are interpreted in terms of scalar comparisons (see also Kennedy and Levin 2008).

We apply this only to dispositional/passive ber- middles since in a reflexive middle the open variable would already be conflated with the subject, and in a lexical NP incorporation middle the distinct XPs expressing the two arguments would preclude such a reading for pragmatic reasons. It is possible in context that the seller in (45) happens to be the same as the wanter in every case, though contingent coreference could also be true with an existential quantifier. It does not clearly reflect a separate reading intended to convey that.

Below we assume DPs may raise for syntactic reasons, and DP-traces represent open variables later λ-abstracted over prior to saturation by their antecedents (building on Heim and Kratzer 1998: 89–98). We ignore the semantics of T (which is irrelevant here) but assume it existentially binds off the event variable e we assume all verbs introduce (Higginbotham 1985: 560–561); nothing hinges on this. Finally, we assume head-movement has no semantic effect, and treat it as reconstructed, effectively ignoring it.

We are not claiming the NP is itself a classifier in the linguistic sense. Indonesian does have some classifiers, e.g. biji ‘thing/round object’ has this function, but does not in fact incorporate (cp. *Dia ber-kirim biji ‘3sg mv-send thing’, “(S)he sent something”). We leave an analysis of such classifiers aside here.

As noted in fn. 12, with cognition middles the surface subject is also the underlying subject, and the clausal complement is preserved. The analysis of incorporation middles here in principle should generate these as well, provided the analysis of both ber- in (43) and incorporation in (49) were generalized to allow for complements beyond those of type e, including whatever semantics the semantic type of a clausal complement is (e.g. a truth value, predicates over world, etc.). At that point the analysis would be otherwise identical, though since CPs presumably do not need to check Case, syntactic incorporation would not strictly speaking be necessary. However, we leave a detailed analysis of clausal complements for future work.

As a reviewer notes, Indonesian independently has nominal predicates, so it is not entirely clear that an incorporation analysis is necessary, though the voice marking suggests the predicate here is verbal and not nominal. Since these data otherwise exhibit the properties of incorporation we maintain this analysis.

There are also reciprocal kin terms like ber-teman ‘be friends.’ We believe the analysis we outline here plus a reciprocal semantics as per fn. 9 can account for those, though we leave the details for separate work.

These forms contrast with another apparently denominal ber- form seemingly formed from sortal nouns and which are inherently reflexive, including ber-kaca ‘mv-mirror’ “look at oneself in a mirror”. Here the reading is always causative and reflexive, paraphrasable by a corresponding meN- -kan form with a reflexive object. However, that the ber-kaca is paraphrasable by a meN- -kan form suggests is derived from that form rather than the noun, similar to the putative deadjectival ber- forms in fn. 11 (though kaca also has a separate clothing meaning of ‘glasses’ and ber-kaca can mean ‘wear glasses’). This is further supported by the fact that diri incorporation is possible (ber-kaca=diri has the same meaning), and stranded modifiers are ruled out, e.g. *ber-kaca baik ‘mv-mirror good’ “look at oneself in a good mirror”. Taken together, ber-kaca and ber-topi are thus not derived in the same way, with the latter but not the former formed from a noun base.

As a reviewer notes, these might be deponents; see Sect. 6. Sneddon (1996: 111–112) also gives denominal ber- -kan forms with specialized possessional readings, though we focus on simple ber-. Another reviewer notes that some institutional nouns form ber- middles, including ber-pendidikan ‘have education,’ ber-pengalaman ‘have experience,’ ber-agama ‘have religion,’ though the reviewer also notes that, as the glosses reflect, these are likely assimilatable to the same analysis as ber-topi. Relatedly, as in fn. 11, if adjectival roots like sedih ‘sad’ have taken on a possessional analysis (‘have sadness’; see Francez and Koontz-Garboden 2017) they could also be assimilated to ber- middles in this section, if X in (64a) can be an adjective.

A reviewer suggests that non-expression of an external argument yields a stronger effect that there is not a corresponding effector in the causing event. This would be surprising given that anticausatives are possible in contexts in which there is clearly an effector (e.g. The window broke—John hit it really hard with a hammer!; see Rappaport Hovav 2014: 25–26). Furthermore, in general verbs can entail unexpressed participants in cases where it is not clear we would want to posit null syntactic representation, as with instruments for verbs of cutting (see e.g. Koenig et al. 2008) and various types of paths, goals, and sources for verbs of motion (see e.g. Beavers 2012a). Thus we do not adopt this further assumption here.

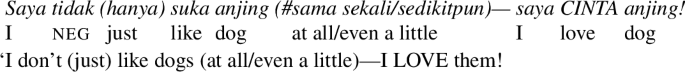

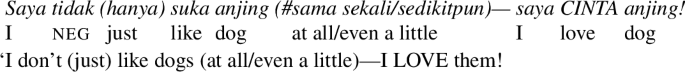

For example, sama sekali/sedikitpun ‘at all/even a little’ are out in the following, unlike hanya ‘just’:

-

(i)

-

(i)

Alternatively it could be that ‘by itself’ is anti-assistive as per Spathas et al. (2015: 1329–1337), introducing an actual entailment that the surface subject is the causer. However, it is debatable that this reading arises for all predicates. For example, contextually supported ‘by itself’ modifiers with statives like Gianni knew the answer by himself, in the context of whether someone fed Gianni the answer (see Alexiadou et al. 2015: 79, (35) for such an example in Italian), do not clearly license internal causation readings per se.

Schäfer and Vivanco (2016) suggest anticausatives are not causative at all but are purely inchoative (see also Rappaport Hovav 2014), though again a reflexive causative reading is possible in context. However, this does not rule out anticausative derivation: although Koontz-Garboden (2009: 123–125) argues that deleting meaning is non-compositional, Beavers (2012b) sketches a compositional “deletion” analysis in terms of constructing the meaning of the anticausative from the causative’s state-denoting lexical semantic constant, but not (necessarily) including causation in the event structure. This would provide a further semantic possibility for ber- that could alternatively characterize anticausatives, though for now we do not develop it further.

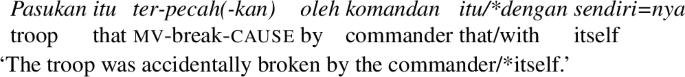

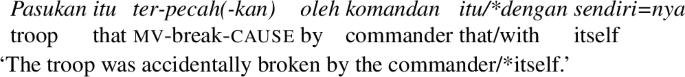

Ter- also marks involuntary passives, which like di- allow oleh ‘by’ PPs but not dengan sendiri=nya:

-

(i)

This is distinct from anticausative formation, applying to more verb types, including activities, e.g. ter-belalai (mv-caress), ter-nyanyikan (mv-sing), which only have passive readings. Thus ter- may be a specialized allomorph of di- as well, or perhaps there is a way to unify them, though we leave a full analysis of ter- aside.

-

(i)

Our comparison here is to comparable narrow descriptive classes such as naturally reflexive or dispositional expressions, etc. As a reviewer notes, a language may categorically lack any unified category of middle altogether. However, our goal is just to see what aspects of what we have proposed might apply across languages rather than to definitively answer what constructions are truly “middle” in some sense.

References

Ackema, Peter, and Maaike Schoorlemmer. 1994. The middle construction and the syntax-semantics interface. Lingua 93: 59–90.

Ackema, Peter, and Maaike Schoorlemmer. 1995. Middles and nonmovement. Linguistic Inquiry 26: 173–198.

Ackema, Peter, and Maaike Schoorlemmer. 2005. Middles. In The Blackwell companion to syntax, eds. Martin Everaert and Henk van Riemsdijk, Vol. III, 131–203. Oxford: Blackwell Sci.

Aldridge, Edith. 2008. Phase-based account of extraction in Indonesian. Lingua 118: 1440–1469.

Aldridge, Edith. 2011. Antipassive in Austronesian alignment change. In Grammatical change: Origins, nature, outcomes, eds. Diane Jones, John Whitman, and Andrew Garrett, 332–346. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Alexiadou, Aartemis, and Edit Doron. 2012. The syntactic construction of two non-active voices: Passive and middle. Journal of Linguistics 48: 1–34.

Alexiadou, Artemis. 2010. On the morpho-syntax of (anti-)causative verbs. In Lexical semantics, syntax and event structure, eds. Malka Rappaport Hovav, Edit Doron, and Ivy Sichel, 177–203. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Alexiadou, Artemis, and Florian Schäfer. 2014. Towards a non-uniform analysis of naturally reflexive verbs. In Proceedings of the 31st west coast conference on formal linguistics, ed. Robert E. Santana-LaBarge, 1–10. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project.

Alexiadou, Artemis, Elena Anagnostopoulou, and Florian Schäfer. 2006. The properties of anti-causatives crosslinguistically. In Phases of interpretation, ed. Mara Frascarelli, 187–211. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Alexiadou, Artemis, Elena Anagnostopoulou, and Florian Schäfer. 2015. External arguments in transitivity alternations: A layering approach. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Alexiadou, Artemis, Berit Gehrke, and Florian Schäfer. 2014a. The argument struture of adjectival passives revisited. Lingua 149: 118–138.

Alexiadou, Artemis, Florian Schäfer, and Giorgos Spathas. 2014b. Delimiting voice in Germanic: On object drop and naturally reflexive verbs. In Proceedings of the Northeast Linguistics Society 45, eds. Jyoti Iyer and Leland Kusmer, 1–14. Storrs: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

Anderson, Mona. 1979. Noun phrase structure. PhD diss., The University of Connecticut.

Baker, Mark C. 1988. Incorporation: A theory of grammatical function changing. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Baker, Mark C. 2009. Is head movement still needed for noun incorporation? Lingua 119: 148–165.

Ball, Douglas. 2005. Tongan noun incorporation: Lexical sharing or argument inheritance. In Proceedings of the 2005 HPSG conference, ed. Stefan Müller, 7–27. Stanford: CSLI.

Barker, Chris. 1995. Possessive descriptions. Stanford: CSLI.

Beaver, David. 1992. The kinematics of presupposition. In Proceedings of the eighth Amsterdam colloquium, eds. Paul Dekker and Martin Stockhof, 17–36. Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam Institute for Language, Logic, and Information.

Beavers, John. 2011. On affectedness. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 29: 335–370.

Beavers, John. 2012a. Lexical aspect and multiple incremental themes. In Telicity, change, and state: A cross-categorial view of event structure, eds. Violeta Demonte and Louise McNalley, 23–59. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Beavers, John. 2012b. On non-agentivity and causer suppression in Colloquial Sinhala. Paper presented at the Workshop on Argument Structure, University of Debrecen, Debrecen, Hungary, May 25–27.

Beavers, John, and Andrew Koontz-Garboden. 2013a. Complications in diagnosing lexical meaning: A rejoinder to Horvath and siloni (2013). Lingua 134: 210–218.

Beavers, John, and Andrew Koontz-Garboden. 2013b. In defense of the reflexivization analysis of anticausativization. Lingua 131: 199–216.

Beavers, John, and Andrew Koontz-Garboden. 2017. Result verbs, scalar change, and the typology of motion verbs. Language 94: 842–876.

Beavers, John, and Andrew Koontz-Garboden. 2020. The roots of verbal meaning. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Beavers, John, and Cala Zubair. 2010. The interaction of transitivity features in the Sinhala involitive. In Transitivity: Form, meaning, acquisition, and processing, eds. Patrick Brandt and Marco Garcia, 69–92. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Beavers, John, and Cala Zubair. 2013. Anticausatives in Sinhala: Involitivity and causer suppression. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 31: 1–46.

Beavers, John, and Cala Zubair. 2016. Anticausatives in Sinhala: A view to the middle. In Proceedings of FASAL 5, eds. Rahul Balusu and Sandhya Sundaresan, 84–108.

Beavers, John, Elias Ponvert, and Stephen Wechsler. 2009. Possession of a controlled substantive: Have and other verbs of possession. In Proceedings of SALT XVIII, eds. Tova Friedman and Satoshi Ito, 108–125. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. http://hdl.handle.net/1813/13029.

Bentley, Delia, and Thórhallur Eythórsson. 2003. Auxiliary selection and the semantics of unaccusativity. Lingua 114: 447–471.

Borer, Hagit. 2005. Structuring sense, vols. I and II. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bruening, Benjamin. 2013. By phrases in passives and nominals. Syntax 16: 1–41.

Burzio, Luigi. 1986. Italian syntax. Dordrecht: Reidel.

Chandralal, Dileep. 2010. Sinhala. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Chappell, Hilary, and William McGregor. 1996. A prolegomena to a theory of inalienability. In The grammar of inalienability: A typological perspective on body part terms and the part-whole relation, eds. Hilary Chappell and William McGregor, 3–30. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Chierchia, Gennaro. 2004. A semantics for unaccusatives and its syntactic consequences. In The unaccusativity puzzle, eds. Artemis Alexiadou, Elena Anagnostopoulou, and Martin Everaert, 22–59. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 1982. Some concepts and consequences of the theory of Government and Binding. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 1995. The minimalist program. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Collins, Chris. 2005. A smuggling approach to the passive in English. Syntax 8: 81–120.

Condoravdi, Cleo. 1989. The middle: Where semantics and morphology meet. In MIT working papers in linguistics 11, 16–31. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Condoravdi, Cleo, and Jean Mark Gawron. 1996. The context-dependency of implicit arguments. In Quantifiers, deduction, and context, eds. Makoto Kanazwa, Christopher Piñón, and Henrietta de Swart, 1–32. Stanford: CSLI.

Croft, William. 1991. Syntactic categories and grammatical relations: The cognitive organization of information. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Croft, William. 2012. Verb: Aspect and causal structure. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dayal, Veneeta. 2011. Hindi pseudo-incorporation. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 29: 123–167.

Doron, Edit. 2003. Agency and voice: The semantics of the Semitic templates. Natural Language Semantics 11: 1–67.

Doron, Edit, and Malka Rappaport Hovav. 2009. A unified approach to reflexivization in Semitic and Romance. Brill’s Annual of Afroasiatic Languages and Linguistics 1: 75–105.

Dowty, David. 1979. Word meaning and Montague Grammar. Dordrecht: Reidel.

Dowty, David. 1989. On the semantic content of the notion ‘thematic role.’ In Properties, types, and meaning, eds. Gennaro Chierchia, Barbara H. Partee, and Raymond Turner. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Embick, David. 1998. Voice systems and the syntax-morphology interface. MIT working papers in linguistics 32: 41–72.

Embick, David. 2004. Unaccusative syntax and verbal alternations. In The unaccusativity puzzle, eds. Artemis Alexiadou, Elena Anagnostopoulou, and Martin Everaert, 137–158. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fábregas, Antonio, and Michael Putnam. 2014. The emergence of middle voice structures with and without agents. The Linguistic Review 33: 193–240.

Fagan, Sarah M. B. 1992. The syntax and semantics of middle constructions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Fortin, Catherine, and Hooi Ling Soh. 2014. Blocking effects and the verbal prefix ber- in Malay and Indonesian. In The 20th annual meeting of the Austronesian formal linguistics association (AFLA 20), ed. Joseph Sabbagh. Arlington: The University of Texas at Arlington.

Francez, Itamar, and Andrew Koontz-Garboden. 2017. Semantics and morphosyntactic variation: Qualities and the grammar of property concepts. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gair, James W. 1970. Colloquial Sinhalese clause structures. The Hague: Mouton.

Gaylord, Nicholas. 2007. Auxiliary selection and the typical properties of subjects. Master’s thesis, The University of Texas at Austin.

Ginzburg, Jonathan, and Ivan A. Sag. 2000. Interrogative investigations: The form, meaning, and use of English interrogatives. Stanford: CSLI.

Grimshaw, Jane. 1982. On the lexical representation of Romance reflexive clitics. In The mental representation of grammatical relations, ed. Joan Bresnan, 87–148. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Hale, Kenneth L., and Samuel Jay Keyser. 2002. Prolegomenon to a theory of argument structure. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Haug, Dag, and Mary Dalrymple. 2019. Reciprocity: Anaphora, scope, and quantification. Unpublished ms., University of Oslo and University of Oxford.

Heim, Irene. 1982. The semantics of definite and indefinite noun phrases. PhD diss., University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Heim, Irene, and Angelika Kratzer. 1998. Semantics in generative grammar. Oxford: Blackwell.

Higginbotham, James. 1985. On semantics. Linguistic Inquiry 16: 547–593.

Horvath, Julia, and Tal Siloni. 2011. Anticaustives: Against reflexivization. Lingua 121: 2176–2186.

Horvath, Julia, and Tal Siloni. 2013. Anticausatives have no cause(r): A rejoinder to Beavers & Koontz-Garboden. Lingua 131: 217–230.

Jaeggli, Osvaldo A. 1986. Passive. Linguistic Inquiry 17: 587–622.

Jeoung, Helen N. 2018. Optional elements in Indonesian morphosyntax. PhD diss, University of Pennsylvania.

Kamp, Hans, and Uwe Ryle. 1993. From dicourse to logic. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Kardana, I Nyoman. 2011. Types of middle voice in Indonesian language (Tipe-tipe diatesis medial dalam bahasa Indonesia). Jurnal Melayu 7: 83–105.

Kaufmann, Ingrid. 2007. Middle voice. Lingua 117: 1677–1714.

Kemmer, Suzanne. 1993. The middle voice. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Kemmer, Suzanne. 1994. Middle voice, transitivity, and the elaboration of events. In Voice: Form and function, eds. Barbara Fox and Paul J. Hopper, 179–230. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Kennedy, Christopher. 2007. Vagueness and grammar: The semantics of relative and absolute gradable adjectives. Linguistics and Philosophy 30: 1–45.

Kennedy, Christopher, and Beth Levin. 2008. Measure of change: The adjectival core of degree achievements. In Adjectives and adverbs: Syntax, semantics, and discourse, eds. Louise McNally and Chris Kennedy, 156–182. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Keyser, Samuel Jay, and Thomas Roeper. 1984. On the middle and ergative constructions in English. Linguistic Inquiry 15: 381–416.

Koenig, Jean-Pierre, Gail Mauner, Greton Bienvenue, and Kathy Conklin. 2008. What with? The anatomy of a (proto)-role. Journal of Semantics 25: 175–220.

Koontz-Garboden, Andrew. 2009. Anticausativization. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 27: 77–138.

Kratzer, Angelika. 1996. Severing the external argument from its verb. In Phrase structure and the lexicon, eds. Johan Rooryck and Laurie Zaring, 109–137. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Kratzer, Angelika. 2000. Building statives. In Annual meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society, 385–399.

Kratzer, Angelika. 2005. Building resultatives. In Event arguments: Functions and applications, eds. Claudia Maienborn and Angelika Wöllstein-Leisten, 177–212. Tübingen: Niemeyer.

Labelle, Marie. 2008. The French reflexive and reciprocal se. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 28: 833–876.

Landau, Idan. 2010. The explicit syntax of implicit arguments. Linguistic Inquiry 41: 357–388.

Landau, Idan. 2015. A two-tiered theroy of control. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Lekakou, Marika. 2002. Middle semantics and its realization in English and Greek. UCL working papers in linguistics 14: 399–416.

Levin, Beth, and Malka Rappaport Hovav. 1995. Unaccusativity: At the syntax-lexical semantics interface. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Lewis, David. 1973. Causation. The Journal of Philosophy 70: 556–567.

Lewis, David. 2000. Causation as influence. The Journal of Philosophy 97: 182–197.

Lundquist, Björn, Martin Corley, Mai Tungseth, Antonella Sorace, and Gillian Ramchand. 2016. Anticausatives are semantically reflexive in Norwegian, but not in English. Glossa 1(1): 47–130.

Maldonado Soto, Ricardo. 1992. Middle voice; the case of Spanish se. PhD diss., University of California, San Diego.

Massam, Diane. 2001. Pseudo-noun incorporation in Niuean. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 19: 153–197.

Mendikoetea, Amaya. 2008. Clitic impersonal constructions in Romance: Syntactic features and semantic interpretation. Transactions of the Philological Society 106: 290–336.

Mendikoetxea, Amaya. 1999a. Construcciones con se: Medias, pasivas e impersonales. In Gramática descriptiva de la lengua Española, eds. Ignacio Bosque and Violeta Demonte, 1631–1722. Madrid: Editorial Espasa.

Mendikoetxea, Amaya. 1999b. Construcciones inacusatives y pasivas. In Gramática descriptiva de la lengua Española, eds. Ignacio Bosque and Violeta Demonte, 1575–1629. Madrid: Editorial Espasa.

Mithun, Marianne. 1984. The evolution of noun incorporation. Language 60: 847–893.

Müller, Stefan, and Stephen Wechsler. 2014. Lexical approaches to argument structure. Theoretical Linguistics 40: 1–76.

Myler, Neil. 2016. Building and interpreting possessive sentences. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Nichols, Johanna. 1988. On alienable and inalienable possession. In In honor of Mary Haas: From the Haas festival conference on Native American linguistics, ed. William Shipley, 557–610. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Ogloblin, Aleksandr K., and Vladimir P. Nedjalkov. 2007. Reciprocal constructions in Indonesian. In Reciprocal constructions, ed. Vladimir P. Nedjalkov, Vol. 3, 1437–1476. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Partee, Barbara H. 1999. Weak NP’s in HAVE sentences. In JFAK [A liber amicorum for Johan van Benthen on the occasion of his 50th birthday], eds. Jelle Gerbrandy, Maarten Marx, Maarten de Rijke, and Yde Venema, 39–57. Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam.

Piñón, Christopher. 2012. The reflexive impersonal construction in Polish. Paper presented at the Workshop on Argument Structure, The University of Debrecen, Debrecen, Hungary, May 25-27.

Pitteroff, Marcel, and Florian Schäfer. 2014. The argument structure of reflexively marked anticausatives and middles: Evidence from datives. In Proceedings of NELS 43, eds. Hsin-Lun Huang, Ethan Poole, and Amanda Rysling, 67–78. Amherst: GLSA.

Polinsky, Maria. 2017. Antipassive. In The Oxford handbook of ergativity, eds. Jessica Coon, Diane Massam, and Lisa Demena Travis, 308–331. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Pollard, Carl, and Ivan A. Sag. 1994. Head-driven phrase structure grammar. Chicago: The University of Chicago.

Pylkkänen, Liina. 2008. Introducing arguments. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Rákosi, György. 2012. In defence of the non-causative analysis of anticausatives. In The theta system, eds. Martin Everaert, Marijana Marelj, and Tal Siloni, 177–199. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rappaport Hovav, Malka. 2014. Lexical content and context: The causative alternation in English revisited. Lingua 141: 8–29.

Reinhart, Tanya. 2002. The theta system - an overview. Theoretical Linguistics 28: 229–290.

Reinhart, Tanya, and Tal Siloni. 2005. The lexicon-syntax parameter: Reflexivization and other arity operations. Linguistic Inquiry 36: 389–436.

Rosen, Sara Thomas. 1989. Two types of noun incorporation: A lexical analysis. Language 65: 294–317.

Sapir, Edward. 1911. The problem of noun incorporation in American languages. American Anthropology 13: 250–282.

Schäfer, Florian. 2009. The causative alternation. Language and Linguistics Compass 3: 641–681.

Schäfer, Florian. 2017. Romance and Greek medio-passives and the typology of Voice. In The verbal domain, eds. Roberta D’Alessandro, Irene Franco, and Ángel J. Gallego, 129–152. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Schäfer, Florian, and Margot Vivanco. 2016. Anticausatives are weak scalar expressions, not reflexive expressions. Glossa 1: 18–136.

Siewierska, Anna. 1984. The passive: A comparative linguistic analysis. London: Croom Helm.

Sneddon, James Neil. 1996. Indonesian: A comprehensive grammar. London: Routledge.

Soh, Hooi Ling. 2013. Voice and aspect: Some notes from Malaysian Malay. In More on voice in languages of Indonesia, eds. Asako Shiohara and Anthony Jukes, 159–173. Tokyo: Tokyo University of Foreign Studies. http://hdl.handle.net/10108/71810.

Soh, Hooi Ling, and Hiroki Nomoto. 2011. The Malay verbal prefix men- and the unergative/unaccusative distinction. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 20: 77–106.

Son, Minjeong, and Peter Cole. 2008. An event-based account of -kan constructions in Standard Indonesian. Language 84: 120–160.

Sorace, Antonella. 2000. Gradients in auxiliary selection with intransitive verbs. Language 76: 859–890.

Spathas, Giorgos, Artemis Alexiadou, and Florian Schäfer. 2015. Middle voice and reflexive interpretations: Afto-prefixation in Greek. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 33: 1293–1350.

Sportiche, Dominique. 2014. Assessing unaccusativity and reflexivity: Using focus alternatives to decide what gets which θ-role. Linguistic Inquiry 45: 305–321.

Stroik, Thomas. 1992. Middles and movement. Linguistic Inquiry 23: 127–137.

Talmy, Leonard. 2000. Toward a cognitive semantics: Typology and process in concept structuring. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Tenny, Carol. 1992. The aspectual interface hypothesis. In Lexical matters, eds. Ivan A. Sag and Anna Szabolcsi, 490–508. Stanford: CSLI.

Tenny, Carol. 1994. Aspectual roles and the syntax-semantic interface. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Tsunoda, Tsaka. 1996. The possession cline in Japanese and other languages. In The grammar of inalienability: A typological perspective on body part terms and the part-whole relation, eds. Hilary Chappell and William McGregor, 565–632. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Udayana, I Nyoman. 1994. The Indonesian reflexive. Master’s thesis, The University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia.

Udayana, I Nyoman. 2011. Middle voice in Indonesian. Unpublished ms., The University of Texas at Austin.

Udayana, I Nyoman. 2017. Reciprocity in Indonesian. In Proceedings of the 8th international seminar on Austronesian and non-Austronesian language and literature in Indonesian, 409–414. Denpasar: Udayana University.

Valpy, Richard. 1814. The elements of Greek grammar, 4th edn. London: A.J. Valpy.

van Oosten, Jeanne. 1977. Subjects and agenthood in English. In Chicago Linguistic Society 13, eds. Woodford A. Beach, Samuel E. Fox, and Shulamith Philosoph, 451–471.

Van Valin, Robert D., Jr., and Randy J. LaPolla. 1997. Syntax: Structure, meaning, and function. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Van Valin, Robert D., Jr., and David P. Wilkins. 1996. The case for ‘effector’: Case roles, agents, and agency revisited. In Grammatical constructions: Their form and meaning, eds. Masayoshi Shibatani and Sandra A. Thompson, 289–322. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Vikner, Carl, and Per Anker Jensen. 2002. A semantic analysis of the English genitive. Interaction of lexical and formal semantics. Studia Linguistica 56: 191–226.

Wechsler, Stephen. 2005. What is right and wrong about little-v. In Grammar and beyond—essays in honour of Lars Hellan, eds. Mila Vulchanova and Tor A. Åfarli, 179–195. Oslo: Novus Press.

Wechsler, Stephen. 2020. The role of the lexicon in the syntax-semantics interface. Annual Review of Linguistics 6: 67–87.

Wescoat, Michael Thomas. 2002. On lexical sharing. PhD diss., Stanford University.

Zaenen, Annie. 1993. Unaccusativity in Dutch: Integrating synatx and lexical semantics. In Semantics and the lexicon, ed. James Pustejovsky, 129–162. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Zwicky, Arnold M., and Jerold M. Sadock. 1975. Ambiguity tests and how to fail them. In Syntax and semantics, ed. John P. Kimball, Vol. 4, 1–36. New York: Academic Press.

Acknowledgements

This paper is a significantly revised and expanded version of Udayana (2011). We are indebted to three anonymous reviewers for their extensive feedback on earlier versions of this paper. We are also grateful to I Wayan Teguh and I Wayan Pastika for their expertise on Balinese and Indonesian and Jufrizal for his knowledge about the Minangkabaunese influence on Indonesian. We also thank David Basilico, Mar Bassa, Isabelle Bril, Gennaro Chierchia, Mary Dalrymple, Itamar Francez, Nissim Francez, Martin Haspelmath, Dag Haug, Hans Kamp, Andrew Koontz-Garboden, Isabel Oltra-Massuet, György Rákosi, Cilene Rodrigues, Steve Wechsler, Yoad Winter, Cala Zubair, Joost Zwarts, and audiences and participants at the 2013 Linguistic Society of America Annual Meeting, the Workshop on Formal Linguistics X, the ROLLING Institute on Argument Structure at Universitate Roveria i Virgili, the University of Texas syntax/semantics seminar, and the first author’s 2019 Word Meaning and Syntax seminar for their feedback. The order of authors is purely alphabetical. Both authors contributed equally to this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Beavers, J., Udayana, I.N. Middle voice as generalized argument suppression. Nat Lang Linguist Theory 41, 51–102 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-022-09542-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-022-09542-5