Abstract

Some utterances of imperative clauses have directive force—they impose obligations. Others have permissive force—they extend permissions. The dominant view is that this difference in force is not accompanied by a difference in semantic content. Drawing on data involving free choice items in imperatives, I argue that the dominant view is incorrect.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

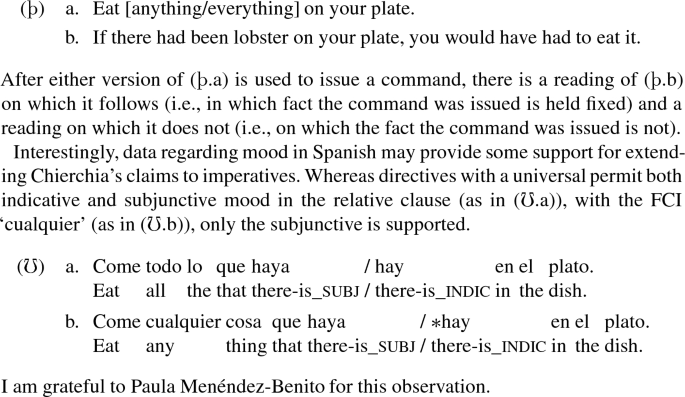

Thanks to Chris Barker, Kyle Blumberg, Pat Brooks, Carolina Flores, Simon Goldstein, Michael Glanzberg, Veronica Gomez-Sanchez, Dan Hoek, Ben Holguin Nico Kirk-Giannini, Jeff King, Annina Loets, Paul Pietroski, Lauren Richardson and Andrew Rubner for comments and judgements. I am especially grateful for the detailed feedback of Paula Menendez Benito and two anonymous referees at Linguistics and Philosophy.

Indeed, I want to leave open the possibility that all imperative clauses have the potential to be used in either way. Even (1) and (2), given a sufficiently exotic context, could be employed with permissive/directive force, respectively.

Portner (2007) does allow that the particular to-do list an imperative is associated with may be lexically specified. However, the semantic value remains a (partial) property of individuals, rather than an update rule on contexts/contextual parameters.

Charlow (2014, 2018) is harder to classify, but follows a similar approach to Kaufmann. He claims that “a semantic theory for a sentence is a theory about what sort of cognitive instruction that sentence proffers”(2014, 655). However, the semantic clause he specifies for imperatives is a function from a plan [ordering source] to a proposition, rather than an update rule (2014, 646).

Assuming semantic homogeneity, whether directives and permissives differ in their update effect will depend, in part, on whether one adopts a pragmatic or semantic account of their dynamics. Most proponents of a pragmatic account, including Portner and Kaufmann, take directives and permissives to be associated with the same update. For Portner, this update amounts to the addition of a property to the ‘to-do list’ of the context. For Kaufmann, the revision of the contextually salient ordering source. For both, however, directives and permissives affect the relevant feature of context in the same way. However, this is not obligatory. It is compatible with a pragmatic account of imperative dynamics that the two differ in their update effect. For example, Halm (2019) proposes that directives and permissives each affect different features of the context, a ‘to-do list’ and a ‘list of actions under consideration’, respectively.

This option is not available to proponents of a semantic account of imperative dynamics who also want to maintain that they are semantically homogenous. If the two have the same content, and the content determines their update effect, then, evidently, that effect cannot vary between them.

This is not to say that illocutionary force should be treated as a property of sentences. Rather, that the fundamental difference between directives and permissives, for semantically heterogenous accounts, will be a difference in meaning, not a difference in illocutionary force (even if the former determines the latter).

In this respect, the account I propose is more similar to that of Krifka (2001, 2004, 2011), who posits that quantifiers may outscope the force of certain clauses, most notably interrogatives. Unlike Krifka, however, I take only sentential force, rather than illocutionary force, to be lexically realized.

I am grateful to Dan Hoek for suggesting the acceptability of ‘by all means’ as a test for permissive force.

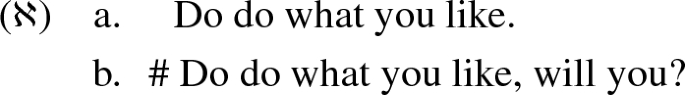

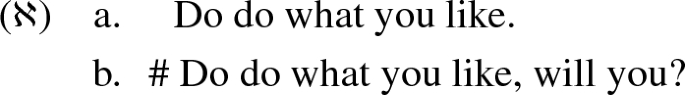

I.e., whereas (\(\aleph \).a) has a licensed, emphatic reading with ‘do’-insertion, (\(\aleph \).b) is marked.

Presumably, this is due to the presence of the competing auxiliary ‘will’ in the latter.

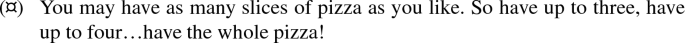

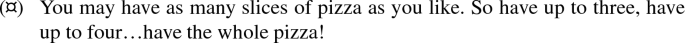

Although (7.b) surely implicates that having four slices of pizza is prohibited, this implicature is cancellable, as in (¤).

I am grateful to an anonymous referee for suggesting this point of comparison.

Approaches which assume semantic heterogeneity (like those defended below) can potentially offer a unified account of the modal and imperative data. By positing distinct operators marking directives and permissives, they can posit that, whereas bounding quantifiers can only occur in the permissives, superlative quantifiers can occur in either. However, regardless of whether a superlative quantifier occurs in a directive or permissive, it serves to impose an obligation (in the same way as both ‘must’ and ‘may’ express obligation in modal declaratives with superlative quantifiers). There remains a question of why permissives or possibility modals express obligations when combined with superlative quantifiers. Cohen and Krifka’s (2014) account of superlative quantifiers in terms of speech act negation offers one way of deriving this effect. If Cohen’s superlative quantifier takes wide scope over a possibility/permissive operator, it will serve to rule out contexts in which the addressee is permitted to eat four slices or more.

While the availability of FCIs in imperatives has been the object of significant discussion, it has largely focused on permissives (like (18.b)) and choice imperatives (Sect. 7.1, (36)–(37)) (Giannakidou 2001; Aloni 2003b, 2007b; Kaufmann 2012; Chierchia 2013; Giannakidou and Quer 2013; Halm 2019). Their occurrence in directives like (18.b), though less commonly discussed, has not been entirely overlooked (Dayal (1998, 464) and Oikonomou (2016b, 57) both note it). However, the variation in the commutativity of the FCI between directives/permissives (as discussed below) has not received attention.

At least with respect to their at-issue content. Plausibly, (19.a) differs from (18.a) in presupposing that there is something on the plate.

Note that this suggests that the licensing conditions of FCI-‘any’ are better predicted along the lines of Dayal’s (2009) ‘fluctuation’ constraint (see below) than by any approach which makes essential appeal to overt post-nominal modification of the complement.

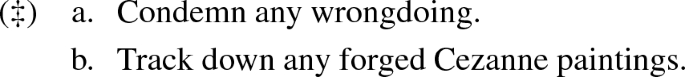

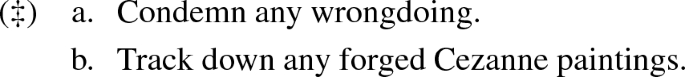

Nor is covert domain restriction required, as suggested by some authors (see in particular, Kaufmann (2012)). When used as religious doctrine, (\(\ddagger \).a) presumably involves unrestricted quantification. Likewise, as instructions to an art investigator, (\(\ddagger \).b) has an acceptable reading without any restriction on the domain (i.e., a reading on which the order is not satisfied if the investigator fails to identify some forgery of a Cezanne).

In this section I focus primarily on discussion of English FCI-‘any’ (along with its derivatives, ‘anything’, ‘anyone’, etc.). However, the analyses I discuss are generally intended to extend to related expressions in other languages, and I will consider the interaction of imperatives and FCIs in a wider range of languages below.

Most, but not all. Rather than having universal force contributed by the determiner itself, Menéndez-Benito (2005, 2010) proposes that it associates with a wide-scope expression with universal force. Likewise, she does not assign FCIs presupposition in (c) to explain their licensing conditions, deriving it from contradictory truth conditions instead. A number of these theories posit slightly different presuppositions to (c) in order to predict the licensing conditions of FCI-‘any’. The differences between these proposals will not matter for present purposes; for simplicitly, I focus on Dayal’s (2009) proposal.

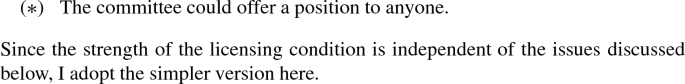

This simplifies Giannakidou and Quer’s formulation of the exhaustive variation condition in two respects. First, they do not specifically identify the relevant domain of individuals with extension of the restrictor. However, in order to obtain the readings they aim to account for, it is clear that this stipulation will be necessary. Second, they impose the stronger requirement that, for each d in the domain of individuals , there is some \( w \in D\) such that \(d\in \llbracket \beta \rrbracket ^{w} \) and there is no \( d '\) in the domain such that \( d'\in \llbracket \beta \rrbracket ^{w} \). It is not obvious that this generates the right predictions however—(\( *\)) appears felicitous even if it is known that the committee has two positions to offer.

Talk of prohibition is intended weakly; in particular, there is no requirement that prohibitions are deontic in character. A condition might get to be prohibited in virtue of being incompatible with the addressee’s self-interest or or the speaker’s desires, for example. In this way, wish-imperatives in English (such as ‘Get well soon.’) can be assimilated to the general class of directives, on the proposal below.

I am grateful to an anonymous referee for directing me towards this material.

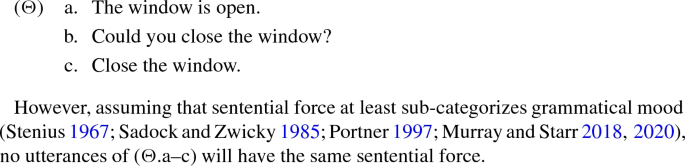

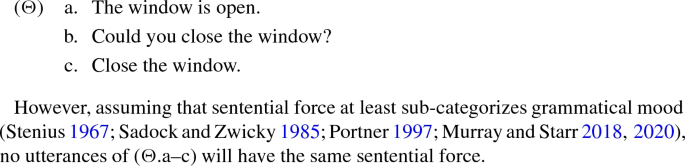

Equally, though less frequently discussed, two utterances which agree in illocutionary force may differ in sentential force. For example, (\(\Theta \).a–c) can each be uttered as a means to performing a request.

An anonymous referee asks why the infelicity of (33) could not be explained by assuming the permissive force operator to take scope over the entire conjunction. Update with such a construction would, indeed, return the absurd context space. However, the problem is not explaining why (33) has a reading on which it is marked, but why, given the assumption that force operators can take scope below conjunction, it does not have a reading on which it is unmarked.

Interestingly, Aloni (2007b, 86) mentions that both a necessity modal and a possibility modal can be derived by applying her imperative operator to an alternative set comprising a contingent proposition paired with \(\bot \) or \(\top \), respectively. This raises the possibility that appropriate force in (18.a–b) could be obtained via this mechanism. While elegant, I can see two challenges for this strategy. The first is how to derive the relevant alternative sets compositionally. The second is that, even if the relevant alternative sets stipulated, there remains no way of predicting the interchangeability of FCI-‘any’ with the standard universal quantifier in (18.a)/(19.a).

The alternative would be for Chierchia to treat (18.b) as sub-trigged. This would yield the equally incorrect prediction that it imposes an obligation to eat everthing in the fridge.

Chierchia’s exhaustification+scope account of FCIs yields a similar prediction when combined with the dynamic approach to imperative meaning suggested above. A directive imperative such as (18.a) will settle eating nothing on your plate as prohibited while simultaneously settling eating each individual item on your plate as permitted. For this reason, wide-scope-binding-based variants of NSI-theories are a better fit with the theory in Sect. 5.1 than exhaustification-based variants.

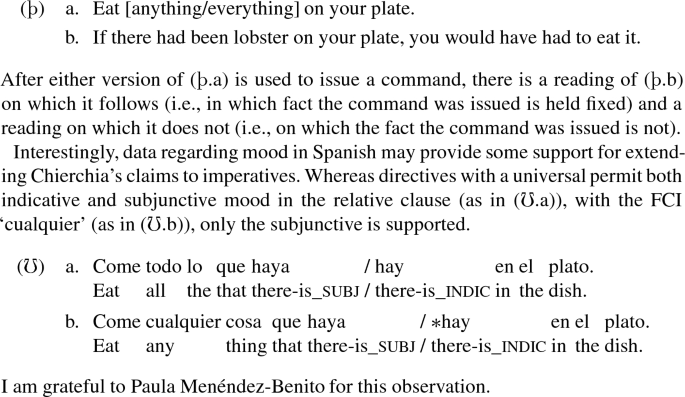

Chierchia suggests that the failure of the inference from ‘every’ to ‘any’ is desirable under necessity modals, since the FCI supports counterfactual inferences not licensed by the standard universal quantifier. This might be correct for (descriptive uses of) declaratives (though the judgments are complex). However, it is not clear that it extends to directives (at least in English).

This assumption is needed to explain the infelicity of, e.g., episodics like ‘Any student must be present’.

Kaufmann (2012, §5.3) does endorse a semantic account of a particular class of permissive imperatives, ones which exhibit what she terms ‘advice’ use. In such uses (which obligatorily involve the parenthetical ‘zum Beispiel’/‘for example’ (in German/English, respectively)), she takes the imperative operator to have the quantificational force of a possibility modal. Its standard interpretation, with the quantificational force of a necessity modal, can then be derived via exhaustification.

Note that the necessity variants improve if it is assumed that it is the domain of cards/keys is unknown. This fails to support the hypothesis that (36)–(37) are directive however. With the assumption of ignorance, the necessity variant of, e.g., (38.a), entails that the address is obligated to press every key. In contrast, the absence of this entailment is precisely what is to be explained in the case of (36).

Or other forms of sub-trigging.

Aloni (2007b) defends an alternative approach, discussed in Sect. 6.1, which takes imperatives to be headed by an operator which expresses neither necessity or possibility, but rather a form of mixed modality (cf. Sect. 6.1). This provides an attractively simple account of choice imperatives like (36)–(37). It also arguably avoids the issues with FCI-licensing that Kaufmann (2012) faces. Aloni suggests revising Kadmon and Landman’s Kadmon and Landman’s (1993) domain widening condition on licensing, from strengthening to non-weakening. If this revision is accepted, the acceptability of the FCI in (36)–(37) can be explained. The acceptability of sequences like (41), however, remains a challenge, as do the issues with non-choice offerning imperatives discussed in the previous section. As an anonymous referee notes, Aloni’s framework can generate the right predictions if (41) is translated as a disjunction of imperatives, although this comes at the cost of allowing disjunction to take scope over sentence boundaries.

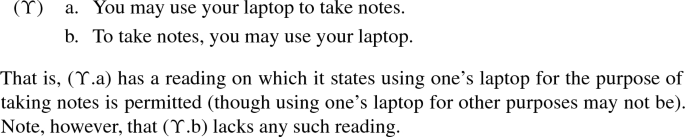

Note that where the infinitive occurs below the modal, the resulting sentence is ambiguous between a practical reading (on which it constrains the domain of quantification) and deontic/epistemic flavor (on which it constrains the action to be performed).

Keshet (2013) proposes an alternative, under which imperatives function to restrict a silent modal taking wide-scope over both clauses. Han (1998) offers an account closest to that defended here, according to which the LH-clause in (45.a) undergoes directive feature deletion. However, she also posits an ambiguity for ‘and’.

Plausibly, (48.c) can receive be interpreted as either endorsing or non-endorsing, depending on context (in particular, whether the speaker desires the addressee to discard the yogurt). All that is relevant is that RNR is unavailable on both interpretations.

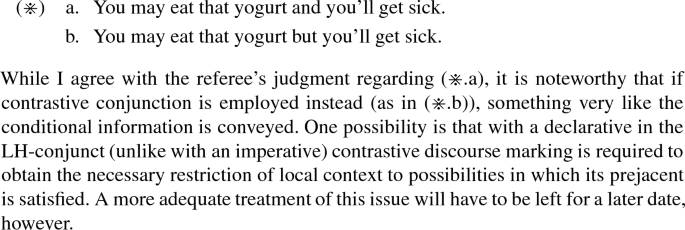

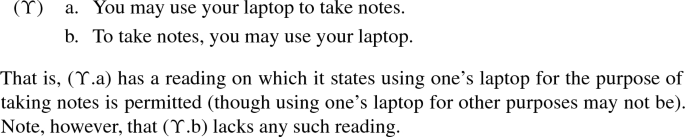

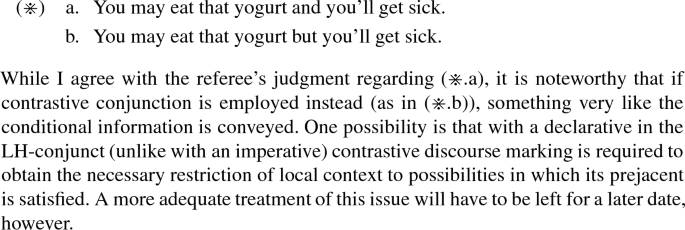

A referee asks why the same conditional information cannot be conveyed by a conjunction with a possibility modal in the LH-conjunct, such as (\(\divideontimes \).a).

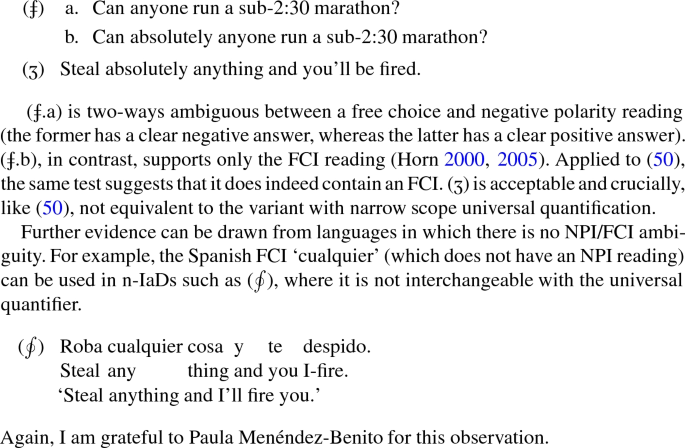

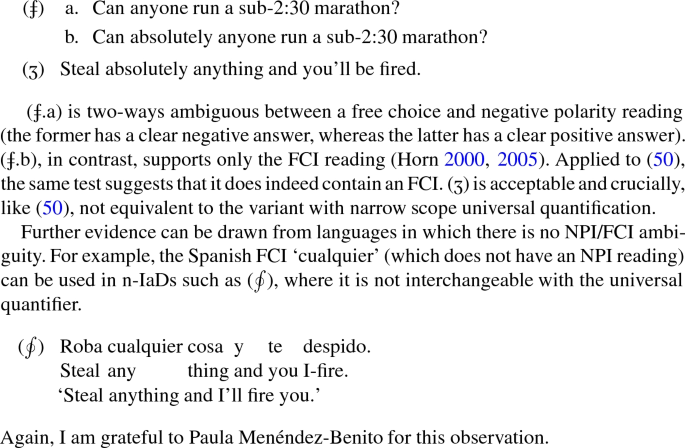

A referee raises the possibility that (50) contains NPI-‘anything’ rather than the FCI. While I agree that n-IaDs license some NPIs in their LH-conjunct, this can be controlled for by considering modifiers such as ‘absolutely’ which combine exclusively with the latter.

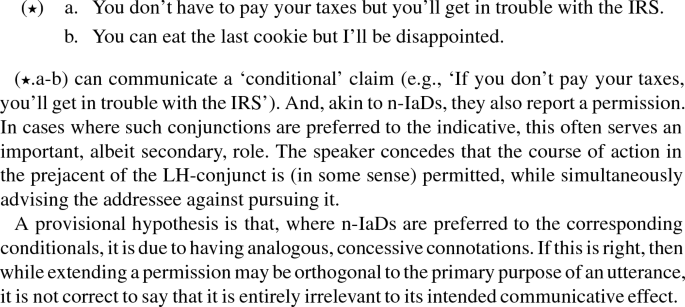

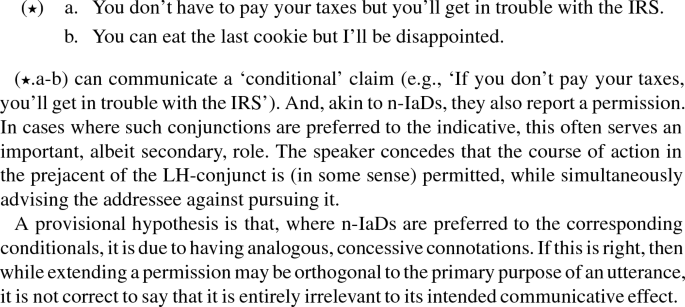

There remains a question of why, if n-IaDs extend permissions, the indicative conditional is not always preferred to convey the same information. Here, it may be helpful to compare n-IaDs with declarative conjunctions like (\(\star \).a–b).

Footnote 46 continued

References

Aloni, M. (2003a). Free choice in modal contexts. Proceedings of Sinn und Bedeutung, 7, 25–37.

Aloni, M. (2003b). On choice-offering imperatives. In Dekker, P., & van Rooy, R. (Eds.), Proceedings of the 14th Amsterdam Colloquium (pp. 25–37). Amsterdam: ILLC.

Aloni, M. (2007a). Free choice and exhaustification: An account of subtriggering effects. Proceedings of Sinn und Bedeutung, 11, 16–30.

Aloni, M. (2007b). Free choice, modals, and imperatives. Natural Language Semantics, 15(1), 65–94.

Beaver, D. (1999). Presupposition accommodation: A plea for common sense. In L. Moss, J. Ginzburg & M. de Rijke (Eds), Logic, language and computation (Vol. 2, pp. 21–44). Stanford: CSLI Publications.

Blok, D. (2015). Scope interactions between modals and modified numerals. In T. Brochhagen, F. Roelofsen, & N. Theiler (Eds.), Proceedings of the 20th Amsterdam Colloquium (pp. 70–79). Amsterdam: ILLC.

Bolinger, D. (1960). Linguistic science and linguistic engineering. WORD, 16(3), 374–391.

Cariani, F., & Santorio, P. (2018). Will done better: Selection semantics, future credence, and indeterminacy. Mind, 127(505), 129–165.

Charlow, N. (2014). Logic and semantics for imperatives. Journal of Philosophical Logic, 43(4), 617–664.

Charlow, N. (2015). Prospects for an expressivist theory of meaning. Philosophers’ Imprint, 15, 1–43.

Charlow, N. (2018). Clause-type, force, and normative judgment in the semantics of imperatives. In D. Fogal, D. Harris, & M. Moss (Eds.), New work on speech acts (pp. 67–98). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chierchia, G. (2006). Broaden your views: Implicatures of domain widening and the logicality of language. Linguistic Inquiry, 37, 535–590.

Chierchia, G. (2013). Logic in grammar: Polarity, free choice and intervention. Oxford: Oxford Univeristy Press.

Chierchia, G., & McConnell-Ginet, S. (1991). Meaning and grammar: An introduction to semantics. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Cinque, G. (1999). Adverbs and functional heads: A cross-linguistic perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cohen, A., & Krifka, M. (2014). Superlative quantifiers and meta-speech acts. Linguistics and Philosophy, 37(1), 41–90.

Condoravdi, C., & Lauer, S. (2012). Imperatives: Meaning and illocutionary force. Empirical Issues in Syntax and Semantics, 9, 37–58.

Culicover, P., & Jackendoff, R. (1997). Semantic subordination despite syntactic coordination. Linguistic Inquiry, 28(2), 195–217.

Davies, E. (1986). The English imperative. Oxford: Routledge.

Dayal, V. (1995). Licensing any in non-negative/non-modal contexts. Proceedings of SALT, 5, 72–93.

Dayal, V. (1998). Any as inherently modal. Linguistics and Philosophy, 21(5), 433–476.

Dayal, V. (2004). The universal force of free choice any. Linguistic Variation Yearbook, 4(01), 5–40.

Dayal, V. (2009). Variation in English free choice items. In R. Mohanty, & M. Menon (Eds.), Universals and variation: Proceedings of GLOW in Asia VII (pp. 237–256). Hyderabad: EFL University Press.

Dayal, V. (2013). A viability constraint on alternatives for free choice. In A. Fălăuşus (Ed.), Alternatives in semantics (pp. 88–122). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Dummett, M. (1973). Frege: Philosophy of language. London: Duckworth.

Eisner, J. (1995). \(\forall \)-less in Wonderland? Revisiting any. In J. Fuller, H. Han, & D. Parkinson (Eds.), Proceedings of ESCOL 11 (October 1994) (pp. 92–103). Ithaca, NY: DMLL Publications.

Francis, N. (2019). Imperatives under ‘Even’. In M. Baird, & J. Pesetsky (Eds.), Proceedings of NELS 49 (Vol. 1, pp. 265–278). Amherst, MA: GLSA.

Frege, G. (1879). Begriffsschrift, eine der arithmetischen nachgebildeten Formelsprache des reinen Denkens. Halle a/S.: Louis Nebert.

Frege, G. (1918). Thoughts. In G. Frege (Ed.), Logical investigations. London: Wiley.

Giannakidou, A. (2001). The meaning of free choice. Linguistics and Philosophy, 24(6), 659–735.

Giannakidou, A., & Quer, J. (2013). Exhaustive and non-exhaustive variation with free choice and referential vagueness: Evidence from Greek, Catalan, and Spanish. Lingua, 126(03), 120–149.

Grosz, P. (2009). German particles, modality, and the semantics of imperatives. In S. Lima, K. Mullin, & B. Smith (Eds.), Proceedings of NELS 39 (pp. 323–336). Amherst, MA: GLSA

Halm, T. (2019). The semantics of weak imperatives revisited: Evidence from free-choice item licensing. Acta Linguistica Academica, 66(12), 445–489.

Han, C.-H. (1998). The structure and interpretation of imperatives: Mood and force in universal grammar. Ph.D. thesis, University of Pennsylvania.

Haspelmath, M. (1997). Indefinite pronouns. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Heim, I. (1982). The semantics of definite and indefinite noun phrases. Ph.D. thesis, UMass Amherst.

Heim, I. (1983). On the projection problem for presuppositions. Reprinted in P. Portner & B. H. Partee (Eds.), Formal semantics: The essential readings (pp. 249–260). Oxford: Wiley, 2002.

Horn, L. (1972). On the semantic properties of logical operators in English. Ph.D. thesis, University of California Los Angeles.

Horn, L. (2000). any and (-)ever: Free choice and free relatives. In A. Z. Wyner (Ed.), Proceedings of the 15th annual conference of the Israeli Association for Theoretical Linguistics (pp. 71–111). Jerusalem: IATL.

Horn, L. (2005). Airport ’86 revisited: Toward a unified indefinite any. In Carlson, G., & Pelletier, F. J. (Eds.), Reference and quantification: The Partee effect (pp. 179–201). Stanford: CSLI Publications.

Hornstein, N. (1990). As time goes by: Tense and universal grammar. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Jary, M., & Kissine, M. (2016). Imperatives as (non-)modals. In J. Blaszczak, A. Giannakidou, D. Klimek-Jankowska, & K. Migdalski (Eds.), Mood, aspect modality revisited: New answers to old questions (pp. 221–242 ). Chicago, IL.: University of Chicago Press.

Jayez, J., & Tovena, L. M. (2005). Free choiceness and non-individuation. Linguistics and Philosophy, 28(1), 1–71.

Jennings, R. E. (1994). The genealogy of disjunction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kadmon, N., & Landman, F. (1993). Any. Linguistics and Philosophy, 16(4), 353–422.

Kamp, H., & Reyle, U. (1993). From discourse to logic. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Karttunen, L. (1972). Possible and must. In J. Kimball (Ed.), Syntax and semantics (Vol. 1, pp. 1–20). New York: Academic Press.

Karttunen, L. (1973). Presuppositions of compound sentences. Linguistic Inquiry, 4(2), 169–193.

Kaufmann, M. (2012). Interpreting imperatives. Dordrecht: Springer.

Kaufmann, M. (2016). Fine-tuning natural language imperatives. Journal of Logic and Computation, 29(3), 321–348.

Keshet, E., & Medeiros, D. J. (2019). Imperatives under coordination. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, 37(3), 869–914.

Keshet, E. (2013). Focus on conditional conjunction. Journal of Semantics, 30(2), 211–256.

Klinedinst, N., & Rothschild, D. (2012). Connectives without truth tables. Natural Language Semantics, 20(2), 137–175.

Kratzer, A., & Shimoyama, J. (2002). Indeterminate pronouns: The view from Japanese. In Otsu, Y. (Ed.), The proceedings of the third Tokyo conference on psycholinguistics (pp. 1–25). Tokyo: Hituzi Syobo.

Kratzer A., & Shimoyama J. (2017). Indeterminate pronouns: The view from Japanese. In C. Lee, F. Kiefer, & M. Krifka (Eds.), Contrastiveness in information structure, alternatives and scalar implicatures (pp. 123–143). Cham: Springer.

Krifka, M. (2001). Quantifying into question acts. Natural Language Semantics, 9(1), 1–40.

Krifka, M. (2004). Semantics below and above speech acts. Stanford University, 9th April, 2004.

Krifka, M. (2011). Questions. In von Heusinger, K., Maienborn, C., & Portner, P. (Eds.), Semantics. An international handbook of natural language meaning (Vol. 2, pp. 1742–1785 ). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Krifka, M. (2014). Embedding illocutionary acts. In Roeper, T., & Speas, M. (Eds.), Recursion, complexity in cognition (pp. 59–87 ). Berlin: Springer.

Krifka, M. (2018). Imperatives in commitment spaces: Conjunction, disjunction, negation and implicit modality. Workshop on Non-Canonical Imperatives Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, 25th–26th May, 2018.

Lauer, S. (2015). Performative uses and the temporal interpretation of modals. In T. Brochhagen, F. Roelofsen, & N. Theiler (Eds.), Proceedings of the 20th Amsterdam Colloquium (pp. 70–79). Amsterdam: ILLC.

Legrand, J. (1975). Or and any: The syntax and semantics of two logical operators. Ph.D. thesis, University of Chicago.

Lewis, D. (1979a). Scorekeeping in a language game. Journal of Philosophical Logic, 8(1), 339–359.

Lewis, D. (1979b). A problem about permission. In Saarinen, E., Hilpinen, R., Niiniluoto, I., & Provence, M. (Eds.), Essays in honour of Jaakko Hintikka on the Occasion of His Fiftieth Birthday on January 12, 1979 (pp. 163–175). Dordrecht: Reidel.

Mastop, R. (2005). What can you do. Ph.D. thesis, University of Amsterdam, ILLC.

Mastop, R. (2011). Imperatives as semantic primitives. Linguistics and Philosophy, 34(4), 305–340.

Menéndez-Benito, P. (2005). The grammar of choice. Ph.D. thesis, UMass Amherst.

Menéndez-Benito, P. (2010). On universal free choice items. Natural Language Semantics, 18(1), 33–64.

Montague, R. (1973). The proper treatment of quantification in ordinary English. In Suppes, P., Moravcsik, J., & Hintikka, J. (Eds.), Approaches to natural language (pp. 221–242). Dordrecht: Reidel.

Murray, S. E., & Starr, W. B. (2018). Force and conversational states. In Fogal, D., Harris, D., & Moss, M. (Eds.), New work on speech acts (pp. 202–236). New York: Oxford University Press.

Murray, S. E., & Starr, W. B. (2020). The structure of communicative acts. Linguistics and Philosophy,https://doi.org/10.1007/s10988-019-09289-0.

Oikonomou, D. (2016a). Covert modals in root clauses. Ph.D. thesis, MIT.

Oikonomou, D. (2016b). Imperatives are existential modals: Deriving the strong reading as an implicature. Semantics and Linguistic Theory, 26(12), 1043.

Penka, D. (2015). At most at last. Proceedings of Sinn und Bedeutung, 19(1), 483–500.

Poletto, C., & Zanuttini, R. (2003). Making imperatives: Evidence from central rhaetoromance. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Portner, P. (1997). The semantics of mood, complementation, and conversational force. Natural Language Semantics, 5(2), 167–212.

Portner, P. (2004). The semantics of imperatives within a theory of clause types. In K. Watanabe, & R. B. Young (Eds.), Proceedings of SALT 14, 235–252.

Portner, P. (2007). Imperatives and modals. Natural Language Semantics, 15(4), 351–383.

Portner, P. (2009). Modality. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Portner, P. (2012). Permission and choice. In G. Grewendorf, & T. E. Zimmermann (Eds.), Discourse and grammar: From sentence types to lexical categories (pp. 43–63). Berlin: de Gruyter.

Portner, P. (2016). Imperatives. In M. Aloni, & P. Dekker (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of formal semantics (pp. 593–626). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Portner, P. (2018). Mood. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Quine, W. V. O. (1960). Word and object. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Reichenbach, H. (1947). Elements of symbolic logic. London: Dover Publications.

Rivero, M. L., & Terzi, A. (1995). Imperatives, V-movement and logical mood. Journal of Linguistics, 31(2), 301–332.

Rizzi, L. (1997). The fine structure of the left periphery. In L. Haegeman (Ed.), Elements of grammar (pp. 281–337). Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Roberts, C. (2016). Conditional plans and imperatives: A semantics and pragmatics for imperative mood. Workshop on imperatives and deontic modals, 20th March, 2016.

Russell, B. (2007). Imperatives in conditional conjunction. Natural Language Semantics, 15(2), 131–166.

Sadock, J. M., & Zwicky, A. M. (1985). Speech acts distinctions in syntax. In Shopen, T. (Ed.), Language typology and syntactic description (pp. 155–196). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Saeboe, K. J. (2001). The semantics of Scandinavian free choice items. Linguistics and Philosophy, 24(6), 737–788.

Schwager, M. (2005). Exhaustive imperatives. In Dekker, P., & Frank, M. (Eds.), Proceedings of the 15th Amsterdam Colloquium (pp. 233–238). Amsterdam: ILLC.

Schwager, M. (2006a). Conditionalized imperatives. Proceedings of SALT, 16, 241–258.

Schwager, M. (2006b). Interpreting imperatives. Ph.D. thesis, Goethe Universität Frankfurt.

Searle, J. R. (1969). Speech acts: An essay in the philosophy of language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Searle, J. R., & Vanderveken, D. (1985). Foundations of illocutionary logic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Stalnaker, R. (2014). Context. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Starr, W. (2018). Conjoining imperatives and declaratives. Proceedings of Sinn und Bedeutung, 21, 1159–1176.

Starr, W. B. (2020). A preference semantics for imperatives. Semantics and Pragmatics, 13(6). https://doi.org/10.3765/sp.13.6.

Starr, W. B. (2014). Force, mood and truth. ProtoSociology, 31, 160–181.

Stenius, E. (1967). Mood and language-game. Synthese, 17(1), 254–274.

Stone, M. (1997). The anaphoric parallel between modality and tense. Techn. report MS-CIS-97-09, University of Pennsylvania.

Veltman, F. (1996). Defaults in update semantics. Journal of Philosophical Logic, 25(3), 221–261.

von Fintel, K., & Iatridou, S. (2017a). A modest proposal for the meaning of imperatives. In Arregui, A., Rivero, M. L., & Salanova, A. (Eds.), Modality across syntactic categories (pp. 288–319). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Von Fintel, K., & Iatridou, S. (2017b). X-marked desires: What wanting and wishing cross-linguistically can tell us about the ingredients of conterfactuality. Lecture notes, MIT.

Willer, M. (2013). Dynamics of epistemic modality. Philosophical Review, 122(1), 45–92.

Williamson, T. (2000). Knowledge and its limits. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix A

Appendix A

A model is a tuple \(\langle {\mathcal {D}}, {\mathcal {W}}, {\mathcal {G}}, \llbracket \cdot \rrbracket \rangle \). \({\mathcal {D}}\) is a set of individuals, \(d, d',\ldots \); \({\mathcal {W}}\) a set of worlds, \(w,w',\ldots \); \({\mathcal {G}}\) a set of assignments, \(g,g',\ldots \); and \(\llbracket \cdot \rrbracket \) an interpretation function.

Definition 1

-

1.

\(\sigma , \sigma ',\ldots \in \mathcal {P(W)}\) are context states;

-

2.

\(\Sigma , \Sigma ',\ldots \in \mathcal {P((P(W)))}\) are context spaces.

We define a language, L, along with a propositional fragment, \(L^{-}.\) \({\textsf {x}, \textsf {x'},\ldots }\) and \({\textsf {F},\textsf {F'},\ldots }\) are schematic variables over sets of (non-schematic) variables and (unary) predicates respectively. \({\textsf {A}, \textsf {B},\ldots }\) and \(\phi ,\psi ,\ldots \) are schematic variables over \(L^{-}\) and L, respectively.

Definition 2

-

1.

-

\( {\textsf {F(x)}}\in L^{-}\);

-

If \({\textsf {A}, \textsf {B}}\in L^{-}, \text { then } \ {\lnot \textsf {A}},\ {\forall \textsf {x}\ {\textsf {A}}},\text { and } ({\textsf {A}\wedge \textsf {B}})\in L^{-} \);

-

Nothing else is in \(L^{-}\).

-

-

2.

-

If \({\textsf {A}}\in L^{-},\) then \({\textsf {A}}, \ \textsc {Dir}({\textsf {A}}) \text { and } \textsc {Prm}({\textsf {A}})\in L\);

-

If \(\phi , \psi \in L\), then \( \lnot \phi , \ \forall {\textsf {x} }\ \phi , \text { and } (\phi \wedge \psi )\in L\);

-

Nothing else is in L.

-

The denotations of expressions in \(L^{-}\) and \({L}/{L}^{-}\) differ in type. The former denote propositions: functions from worlds to truth values (type: \(\langle s, t\rangle \)). The latter denote context change potentials: functions between conversation systems (type: \(\langle \langle st,t\rangle , \langle st,t\rangle \rangle \)).

\((\cdot )'\) is a generalized complementation operation over expressions of type \(\langle \alpha , \beta \rangle \) (where \(\beta \) ‘ends in t’).

\(\sqcap \) is a generalized intersection operation over two expressions of type \(\langle \alpha , \beta \rangle \) (where \(\beta \), again, ‘ends in t’). \(\sqcap \) is the derivatively defined n-ary operation.

In interpreting our language, we define a single interpretation function recursively over the entirety of L.

Definition 3

-

1.

\(\llbracket {\textsf {F(x)}} \rrbracket ^{g}=\lambda w. g(\textsf {x})\in w({\textsf {F}}). \)

-

2.

\(\llbracket {\textsc {Dir}}({\textsf {A}}) \rrbracket ^{g}=\lambda \Sigma \lambda \sigma :\sigma \in \Sigma . \ \sigma \subseteq \llbracket {\textsf {A}}\rrbracket ^{g} \)

-

3.

\(\llbracket {\textsc {Prm}}({\textsf {A}}) \rrbracket ^{g}=\lambda \Sigma \lambda \sigma :\sigma \in \Sigma . \ \sigma \cap \llbracket {\textsf {A}}\rrbracket ^{g}\not =\emptyset \)

-

4.

\(\llbracket \lnot \mathsf{\phi } \rrbracket ^{g}= (\llbracket \mathsf{\phi }\rrbracket ^{g})'\)

-

5.

\(\llbracket \phi \wedge \psi \rrbracket ^{g}=\llbracket \phi \rrbracket ^{g}\sqcap \llbracket \psi \rrbracket ^{g}\)

-

6.

\(\llbracket \forall \textsf {x} \phi \rrbracket ^{g}=\sqcap _{d\in {\mathcal {D}} } \ \llbracket \phi \rrbracket ^{g[{\textsf {x}}\rightarrow d]}\)

\(\llbracket {\textsf {F(x)}}\rrbracket ^{g}\) is the set of worlds w which map F to an extension which includes \(g({\textsf {x}})\). \(\llbracket {\textsc {Dir}}({\textsf {A}}) \rrbracket ^{g}\) maps \(\Sigma \) to the set of its elements which are subsets of \(\llbracket {\textsf {A}}\rrbracket ^{g}\). \(\llbracket {\textsc {Prm}}({\textsf {A}}) \rrbracket ^{g}\) maps \(\Sigma \) to the set of its elements which have a non-empty intersection with \(\llbracket {\textsf {A}}\rrbracket ^{g}\). Given an input \(\Sigma \), \(\llbracket {\textsc {Dir}}({\textsf {A}})\rrbracket ^{g}\) and \(\llbracket {\textsc {Prm}}({\textsf {A}})\rrbracket ^{g}\) are defined on a context state \(\sigma \) iff \(\sigma \in \Sigma \).

\(\llbracket \lnot \mathsf{\phi } \rrbracket ^{g}\) is the generalized complement of \(\llbracket { \phi } \rrbracket ^{g}\). \(\llbracket \phi \wedge \psi \rrbracket ^{g}\) is the generalized intersection of \(\llbracket \phi \rrbracket ^{g}\) and \(\llbracket \psi \rrbracket ^{g}\). \(\llbracket \forall \textsf {x} \phi \rrbracket ^{g}\) is the generalized n-ary intersection of the set \(\{ \llbracket \phi \rrbracket ^{g[\mathsf{x\rightarrow d} ]}\ :\ d\in {\mathcal {D}} \}\).

Adopting post-fix notation, we write \(\Sigma \llbracket \phi \rrbracket ^{g}\) for \(\llbracket \phi \rrbracket ^{g}(\Sigma ).\) Finally, we define relations of support and entailment.

Definition 4

-

1.

iff \(\Sigma =\Sigma \llbracket \phi \rrbracket ^{g}\)

iff \(\Sigma =\Sigma \llbracket \phi \rrbracket ^{g}\) -

2.

iff for all g and all \(\Sigma \):

iff for all g and all \(\Sigma \):  .

.

\(\Sigma \) supports \(\phi \) (relative to g) iff it is a fixed point of update with \(\llbracket \phi \rrbracket ^{g}\). \(\phi _{i},\ldots ,\phi _{j}\) entail \(\psi \) iff for any assignment g and context space, \(\Sigma \), sequential update of \(\Sigma \) with \(\llbracket \phi _{i}\rrbracket ^{g},\ldots ,\llbracket \phi _{j}\rrbracket ^{g}\) supports \(\psi \) (relative to g).

We can now make some observations about our language. Fact 1 says that Prm is the dual of Dir.

Fact 1

Proof

By Definition 3.2, we know that \(\Sigma \llbracket \textsc {Dir}(\textsf {A})\rrbracket ^{g}=\{\sigma \in \Sigma \ :\ \sigma \subseteq \llbracket {\textsf {A}}\rrbracket ^{g} \}\). By Definition 3.4, we know that \(\llbracket \lnot \textsc {Prm}(\lnot {{\textsf {A}}})\rrbracket ^{g}=(\llbracket \textsc {Prm}(\lnot {\textsf {A}})\rrbracket ^{g})'\), the generalized complement of \(\llbracket \textsc {Prm}(\lnot {\textsf {A}})\rrbracket ^{g}\). But observe that \(\Sigma (\llbracket \textsc {Prm}(\lnot {\textsf {A}})\rrbracket ^{g})'=\{\sigma \in \Sigma \ : \ \sigma \cap \llbracket { \lnot {\textsf {A}}}\rrbracket ^{g}=\emptyset \}\). Since \(\sigma \cap \llbracket \lnot {\textsf {A}}\rrbracket ^{g}=\emptyset \) iff \(\sigma \subseteq \llbracket {\textsf {A}}\rrbracket ^{g}\), it follows that for any g: \(\llbracket \textsc {Dir}(\textsf {A})\rrbracket ^{g}=\llbracket \lnot \textsc {Prm}(\lnot {\textsf {A}})\rrbracket ^{g}\). A fortiori, for any g,  and

and  . \(\square \)

. \(\square \)

Fact 2.1 says that \(\forall \mathsf{x}\) commutes with Dir. Fact 2.2 says that \(\forall \mathsf{x}\) does not commute with Prm.

Fact 2

-

1.

-

2.

Proof

Starting with Fact 2.1, first, note that updating a context \(\Sigma \) with \(\llbracket \forall {\textsf {x}}\ \textsc {Dir}({\textsf {A}})\rrbracket ^{g}\) returns the new context space \(\bigcap _{d\in {\mathcal {D}}}\{\sigma \in \Sigma \ : \ \sigma \subseteq \llbracket {\textsf {A}}\rrbracket ^{g[{\textsf {x}}\rightarrow d]} \}\). Similarly, updating \(\Sigma \) with \(\llbracket \textsc {Dir}(\forall {\textsf {x}} \ {\textsf {A}})\rrbracket ^{g}\) returns the new context space \(\{\sigma \in \Sigma \ : \ \sigma \subseteq \llbracket { \forall {\textsf {x}} \textsf {A}}\rrbracket ^{g} \}\). Note that \(\llbracket {\forall {\textsf {x}} \textsf {A}}\rrbracket ^{g}=\bigcap _{d\in {\mathcal {D}}} \llbracket {\textsf {A}}\rrbracket ^{g[{\textsf {x}}\rightarrow d]}\). So \(\Sigma \llbracket \textsc {Dir}(\forall {\textsf {x}} \ {\textsf {A}})\rrbracket ^{g}\) is the set \(\{\sigma \in \Sigma \ : \ \sigma \subseteq \bigcap _{d\in {\mathcal {D}}} \llbracket {\textsf {A}}\rrbracket ^{g[{\textsf {x}}\rightarrow d]}\}\).

But observe that, by elementary set theory, \(\bigcap _{d\in {\mathcal {D}}}\{\sigma \in \Sigma \ : \ \sigma \subseteq \llbracket {\textsf {A}}\rrbracket ^{g[{\textsf {x}}\rightarrow d]} \} =\{\sigma \in \Sigma \ : \ \sigma \subseteq \bigcap _{d\in {\mathcal {D}}} \llbracket {\textsf {A}}\rrbracket ^{g[{\textsf {x}}\rightarrow d]}\}.\) It follows that for any g, \(\llbracket \forall {\textsf {x}}\ \textsc {Dir}({\textsf {A}})\rrbracket ^{g}=\llbracket \textsc {Dir}(\forall {\textsf {x}} \ {\textsf {A}})\rrbracket ^{g}\). Accordingly, for any g and \(\Sigma \),  and

and  . \(\square \)

. \(\square \)

Turning to Fact 2.2, first, note that updating a context space \(\Sigma \) with \(\llbracket \forall {\textsf {x}}\ \textsc {Prm}({\textsf {A}})\rrbracket ^{g}\) returns the new context space \(\bigcap _{d\in {\mathcal {D}}} \{\sigma \in \Sigma \ : \ \sigma \cap \llbracket {\textsf {A}}\rrbracket ^{g[{\textsf {x}}\rightarrow d]} \not =\emptyset \}\). Similarly, updating \(\Sigma \) with \(\llbracket \textsc {Prm}(\forall {\textsf {x}} \ {\textsf {A}})\rrbracket ^{g}\) returns the new context space \(\{\sigma \in \Sigma \ : \ \sigma \cap \llbracket \forall {\textsf {x}} \ {\textsf {A}}\rrbracket ^{g} \not =\emptyset \}\). Note that \(\llbracket {\forall {\textsf {x}}} \textsf {A}\rrbracket ^{g}=\bigcap _{d\in {\mathcal {D}}} \llbracket {\textsf {A}}\rrbracket ^{g[{\textsf {x}}\rightarrow d]}\). So \(\Sigma \llbracket \textsc {Prm}(\forall {\textsf {x}} \ {\textsf {A}})\rrbracket ^{g}\) is the set \(\{\sigma \in \Sigma \ : \ \sigma \cap (\bigcap _{d\in {\mathcal {D}}} \llbracket {\textsf {A}}\rrbracket ^{g[{\textsf {x}}\rightarrow d]})\not =\emptyset \}\).

We know that  . So

. So

However, crucially, \(\bigcap _{d\in {\mathcal {D}}} \{\sigma : \ \sigma \cap \llbracket {\textsf {A}}\rrbracket ^{g[{\textsf {x}}\rightarrow d]} \not =\emptyset \}\not \subseteq \{\sigma : \ \sigma \cap (\bigcap _{d\in {\mathcal {D}}} \llbracket \mathsf{A}\rrbracket ^{g[{\textsf {x}}\rightarrow d]})\not =\emptyset \} \). Thus,  .

.

As a countermodel, suppose that \({\mathcal {W}}=\{w,v\}\) and \({\mathcal {D}}=\{d,d'\}\), letting \(w({\textsf {F}})=\{d\}\) and \(v({\textsf {F}})=\{d'\}\). Consider the context space \(\Sigma =\{ \{w,v \}\}\). \(\Sigma \) is a fixed point of \(\llbracket \forall \mathsf{x}\ \textsc {Prm}(\mathsf{A}) \rrbracket ^{g}\), since \(w\in \llbracket {F(\textsf {x})}\rrbracket ^{g[\textsf {x}\rightarrow d]}\) and \(v\in \llbracket {\textsf { F(x)}}\rrbracket ^{g[{\textsf {x}}\rightarrow d']}\). However, updating \(\Sigma \) with \(\llbracket \ \textsc {Prm}(\forall \mathsf{x}\ {\textsf {A}}) \rrbracket ^{g}\) returns \(\{\{\}\}\), the absurd space, since \(\bigcap _{d\in {\mathcal {D}}} \llbracket {\textsf {F(x)}}\rrbracket ^{g[{\textsf {x}}\rightarrow d]}=\emptyset \).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Carter, S. Force and Choice. Linguist and Philos 45, 873–910 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10988-021-09335-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10988-021-09335-w

):

):

iff

iff  iff for all g and all

iff for all g and all  .

.