Abstract

Background

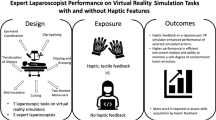

Laparoscopy requires specific psychomotor skills and can be challenging to learn. Most proficiency-based laparoscopic training programs have used non-haptic virtual reality simulators; however, haptic simulators can provide the tactile sensations that the surgeon would experience in the operating room. The objective was to investigate the effect of adding haptic simulators to a proficiency-based laparoscopy training program.

Methods

A randomized controlled trial was designed where residents (n = 36) were randomized to proficiency-based laparoscopic simulator training using haptic or non-haptic simulators. Subsequently, participants from the haptic group completed a follow-up test, where they had to reach proficiency again using the non-haptic simulator. Participants from the non-haptic group returned to train until reaching proficiency again using the non-haptic simulator.

Results

Mean completion times during the intervention were 120 min (SD 38.7 min) and 183 min (SD 66.3 min) for the haptic group and the non-haptic group, respectively (p = 0.001). The mean times to proficiency during the follow-up test were 107 min (SD 41.0 min) and 58 min (SD 23.7 min) for the haptic and the non-haptic group, respectively (p < 0.001). The haptic group was not faster to reach proficiency in the follow-up test than during the intervention (p = 0.22). In contrast, the non-haptic group reached the required proficiency level significantly faster in the follow-up test (p < 0.001).

Conclusion

Haptic virtual reality simulators reduce the time to reach proficiency compared to non-haptic simulators. However, the acquired skills are not transferable to the conventional non-haptic setting.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Barnes RW, Lang NP, Whiteside MF (1989) Halstedian technique revisited. Innovations in teaching surgical skills. Ann Surg 210(1):118–121

Dankelman J, Grimbergen CA (2005) Systems approach to reduce errors in surgery. Surg Endosc 19(8):1017–1021

Reznick RK, MacRae H (2006) Teaching surgical skills–changes in the wind. N Engl J Med 355(25):2664–2669

Fried GM et al (2004) Proving the value of simulation in laparoscopic surgery. Ann Surg 240(3):518–525 (discussion 525–528)

Seymour NE et al (2002) Virtual reality training improves operating room performance: results of a randomized, double-blinded study. Ann Surg 236(4):458–463 (discussion 463–464)

Våpenstad C, Buzink SN (2013) Procedural virtual reality simulation in minimally invasive surgery. Surg Endosc 27(2):364–377

Zendejas B et al (2013) State of the evidence on simulation-based training for laparoscopic surgery: a systematic review. Ann Surg 257(4):586–593

Larsen CR et al (2009) Effect of virtual reality training on laparoscopic surgery: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 338:b1802

Ahlberg G et al (2007) Proficiency-based virtual reality training significantly reduces the error rate for residents during their first 10 laparoscopic cholecystectomies. Am J Surg 193(6):797–804

Bashankaev B, Baido S, Wexner SD (2011) Review of available methods of simulation training to facilitate surgical education. Surg Endosc 25(1):28–35

Gurusamy KS et al (2009) Virtual reality training for surgical trainees in laparoscopic surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 1:Cd006575

Gallagher AG et al (2005) Virtual reality simulation for the operating room: proficiency-based training as a paradigm shift in surgical skills training. Ann Surg 241(2):364–372

Larsen CR et al (2006) Objective assessment of gynecologic laparoscopic skills using the LapSimGyn virtual reality simulator. Surg Endosc 20(9):1460–1466

Ottermo MV et al (2006) The role of tactile feedback in laparoscopic surgery. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 16(6):390–400

Lamata P et al (2006) Study of laparoscopic forces perception for defining simulation fidelity. Stud Health Technol Inform 119:288–292

Tholey G, Desai JP, Castellanos AE (2005) Force feedback plays a significant role in minimally invasive surgery: results and analysis. Ann Surg 241(1):102–109

Chmarra MK et al (2008) Force feedback and basic laparoscopic skills. Surg Endosc 22(10):2140–2148

Westebring-van der Putten EP et al (2009) Effect of laparoscopic grasper force transmission ratio on grasp control. Surg Endosc 23(4):818–824

Panait L et al (2009) The role of haptic feedback in laparoscopic simulation training. J Surg Res 156(2):312–316

Salkini MW et al (2010) The role of haptic feedback in laparoscopic training using the LapMentor II. J Endourol 24(1):99–102

Rangarajan K, Davis H, Pucher PH (2020) Systematic review of virtual haptics in surgical simulation: a valid educational tool? J Surg Educ 77(2):337–347

Våpenstad C et al (2017) Lack of transfer of skills after virtual reality simulator training with haptic feedback. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol 26(6):346–354

Hiemstra E et al (2011) Virtual reality in laparoscopic skills training: is haptic feedback replaceable? Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol 20(3):179–184

Cao CG et al (2007) Can surgeons think and operate with haptics at the same time? J Gastrointest Surg 11(11):1564–1569

Zhou M et al (2012) Effect of haptic feedback in laparoscopic surgery skill acquisition. Surg Endosc 26(4):1128–1134

Kim HK, Rattner DW, Srinivasan MA (2004) Virtual-reality-based laparoscopic surgical training: the role of simulation fidelity in haptic feedback. Comput Aided Surg 9(5):227–234

Ström P et al (2006) Early exposure to haptic feedback enhances performance in surgical simulator training: a prospective randomized crossover study in surgical residents. Surg Endosc 20(9):1383–1388

Wottawa CR et al (2013) The role of tactile feedback in grip force during laparoscopic training tasks. Surg Endosc 27(4):1111–1118

Bjerrum F et al (2015) Effect of instructor feedback on skills retention after laparoscopic simulator training: follow-up of a randomized trial. J Surg Educ 72(1):53–60

Cuschieri S (2019) The CONSORT statement. Saudi J Anaesth 13(Suppl 1):S27–S30

Konge L et al (2015) The simulation centre at Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen, Denmark. J Surg Educ 72(2):362–365

Sørensen SMD, Konge L, Bjerrum F (2017) 3D vision accelerates laparoscopic proficiency and skills are transferable to 2D conditions: a randomized trial. Am J Surg 214(1):63–68

Hagelsteen K et al (2019) Performance and perception of haptic feedback in a laparoscopic 3D virtual reality simulator. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol 28(5):309–316

Winstein CJ, Pohl PS, Lewthwaite R (1994) Effects of physical guidance and knowledge of results on motor learning: support for the guidance hypothesis. Res Q Exerc Sport 65(4):316–323

Salmoni AW, Schmidt RA, Walter CB (1984) Knowledge of results and motor learning: a review and critical reappraisal. Psychol Bull 95(3):355–386

Strandbygaard J et al (2013) Instructor feedback versus no instructor feedback on performance in a laparoscopic virtual reality simulator: a randomized trial. Ann Surg 257(5):839–844

Larsen CR, Sørensen JL, Ottesen BS (2006) Simulation training of laparoscopic skills in gynaecology. Ugeskr Laeger 168(33):2664–2668

Andersen SAW et al (2020) Reliable assessment of surgical technical skills is dependent on context: an exploration of different variables using generalizability theory. Acad Med 95(12):1929–1936

Bjork EL, Bjork RA (2011) Making things hard on yourself, but in a good way: creating desirable difficulties to enhance learning. Psychol Real World: Essays Illustrat Fundam Contrib Soc 2:59–68

Ali MR et al (2002) Training the novice in laparoscopy. More challenge is better. Surg Endosc 16(12):1732–1736

Oestergaard J et al (2012) Instructor feedback versus no instructor feedback on performance in a laparoscopic virtual reality simulator: a randomized educational trial. BMC Med Educ 12:7

Favier V et al (2021) Haptic fidelity: the game changer in surgical simulators for the next decade? Front Oncol 11:713343

Våpenstad C et al (2013) Limitations of haptic feedback devices on construct validity of the LapSim® virtual reality simulator. Surg Endosc 27(4):1386–1396

Sakakushev BE et al (2017) Striving for better medical education: the simulation approach. Folia Med (Plovdiv) 59(2):123–131

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosures

Anishan Vamadevan, Morten Stadeager, Lars Konge, Flemming Bjerrum have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Basic skill 1: Instrument navigation.

Parameter | Requirement for proficiency level |

|---|---|

Left instrument time (s) | < 25 |

Left instrument misses | < 2 |

Left instrument path length (m) | < 1.4 |

Left instrument angular path (degrees) | < 250 |

Right instrument time (s) | < 25 |

Right instrument misses | < 2 |

Right instrument path length (m) | < 1.4 |

Right instrument angular path (degrees) | < 250 |

Tissue Damage | < 5 |

Maximum Damage (mm) | < 10 |

Basic skill 2: Grasping.

Parameter | Requirements for proficiency level |

|---|---|

Left instrument time (s) | < 45 |

Left instrument path length (m) | < 2 |

Left instrument angular path (degrees) | < 300 |

Right instrument time (s) | < 45 |

Right instrument path length (m) | < 2 |

Right instrument angular path (degrees) | < 300 |

Tissue damage (frequency) | < 3 |

Basic skill 3: Lifting and grasping.

Parameter requirements for proficiency level | Requirements for proficiency level |

|---|---|

Total time (s) | < 120 |

Left instrument misses (%) | < 60 |

Left instrument path length (m) | < 3.2 |

Left instrument angular path (degrees) | < 600 |

Right instrument misses (%) | < 60 |

Right instrument path length (m) | < 3.2 |

Right instrument angular path (degrees) | < 600 |

Tissue damage (frequency) | < 5 |

Maximum damage (mm) | < 15 |

Grasper collided with left box (frequency) | < 10 |

Left box lifted (frequency) | < 15 |

Grasper collided with right box (frequency) | < 10 |

Basic skills 4: Fine dissection.

Parameters | Requirements for proficiency level |

|---|---|

Total time (s) | < 150 |

Ripped or burned blood vessels | < 0 |

Energy damaged on blood vessels (%) | < 20 |

Ripped small vessels (%) | < 25 |

Burned small vessels with or without stretch (%) | < 25 |

Grasper path length (m) | < 0.5 |

Grasper angular path (degrees) | < 120 |

Grasper outside view (frequency) | < 2 |

Grasper outside view (s) | < 4 |

Cutter path length (m) | < 0.9 |

Cutter path length (m) | < 0.8 |

Cutter angular path (degrees) | < 200 |

Cutter outside view (frequency) | < 2 |

Cutter outside view (s) | < 4 |

Procedural modul: Ectopic Pregnancy.

Parameters for the procedure: salpingectomy on the Lapsim® virtual reality simulator. To reach the proficiency level all the requirements for the proficiency level must be fulfilled using correct operation technique.

Parameters | Requirements for proficiency level |

|---|---|

Total time (s) | < 280 |

Left instrument path length (m) | < 2 |

Left instrument angular path (degrees) | < 350 |

Right instrument path length (m) | < 3 |

Right instrument angular path (degrees) | < 450 |

Blood loss (ml) | < 180 |

Pool of blood (ml) | < 10 |

Ovary Diathermy damage (s) | < 3 |

Tube Cut: Uterus distance (mm) | < 10 |

Removed dissected tissue (Yes/No) | Yes |

Bleeding vessel cut (Yes/No) | No |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Vamadevan, A., Konge, L., Stadeager, M. et al. Haptic simulators accelerate laparoscopic simulator training, but skills are not transferable to a non-haptic simulator: a randomized trial. Surg Endosc 37, 200–208 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-022-09422-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-022-09422-4