Abstract

Aim

Hormones play a crucial role in growth development; however, the impact of testosterone suppression (TS) on craniofacial growth during puberty remains inconclusive. This study aimed to evaluate the impact of TS during puberty on cephalometric measurements and histological characteristics of facial growth centers.

Materials and methods

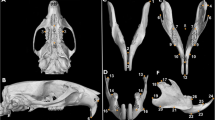

Thirty-six heterogenic Wistar male rats were randomly allocated into experimental orchiectomy (ORX) and control (sham) groups. At an age of 23 days (prepubertal stage), orchiectomy and placebo surgery were performed. Cephalometric measurements were performed via lateral cephalograms during and after puberty. The animals were euthanized at an age of 45 days (pubertal stage) and 73 days (postpubertal stage). Histological slices of the growth centers (condyle, premaxilla, and median palatine suture) were stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and sirius red. Student’s t or Mann–Whitney U tests were used to compare linear and angular cephalometric measurements across groups (α error = 5%).

Results

Linear and angular measurements were statistically different in ORX animals (cranial bones, maxilla, and mandible) at 45 days and 73 days. Condylar histology showed a decrease in prechondroblast differentiation and a delay of mineralization in ORX animals. Vascularization of the medium palatine suture was lower in the ORX group at 45 days. Type I and III collagen fiber synthesis was lower in the ORX groups. In the premaxillary suture, collagen fibers were better organized in the sham groups.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that testosterone suppression affects craniofacial growth during puberty.

Zusammenfassung

Ziel

Hormone sind von entscheidender Bedeutung für die Wachstumsentwicklung; die Auswirkungen einer Testosteronsuppression (TS) auf das kraniofaziale Wachstum während der Pubertät sind jedoch noch nicht eindeutig geklärt. Ziel dieser Studie war es, die Auswirkungen einer TS während der Pubertät auf kephalometrische Maße und histologische Parameter der fazialen Wachstumszentren zu untersuchen.

Material und Methoden

Heterogene männliche Wistar-Ratten (n = 36) wurden nach dem Zufallsprinzip einer experimentellen Orchiektomie (ORX) und einer Kontrollgruppe (Sham) zugeteilt. Im Alter von 23 Tagen (präpubertäres Stadium) wurden die Orchiektomien bzw. die Placebooperationen durchgeführt. Während und nach der Pubertät wurden kephalometrische Messungen mithilfe von lateralen Kephalogrammen durchgeführt. Die Tiere wurden im Alter von 45 (pubertäres Stadium) und 73 Tagen (postpubertäres Stadium) eingeschläfert. Histologische Schnitte der Wachstumszentren (Kondylen, Prämaxilla und mediane Gaumennaht) wurden mit Hämatoxylin-Eosin und Siriusrot gefärbt. Zum Vergleich der linearen und angulären kephalometrischen Messungen zwischen den Gruppen wurden der Student-t-Test bzw. der Mann-Whitney-U-Test verwendet (α-Fehler = 5 %).

Ergebnisse

Die linearen und angulären Messungen waren bei ORX-Tieren (Schädelknochen, Ober- und Unterkiefer) nach 45 und 73 Tagen statistisch unterschiedlich. Die Histologie der Kondylen zeigte eine Abnahme der Prächondroblastendifferenzierung und eine Verzögerung der Mineralisierung bei den ORX-Tieren. Die Vaskularisierung der mittleren Gaumennaht war in der ORX-Gruppe nach 45 Tagen geringer ausgeprägt, ebenso wie die Synthese von Typ-I- und Typ-III-Kollagenfasern. In der Prämaxillarnaht waren die Kollagenfasern in den Sham-Gruppen besser organisiert.

Schlussfolgerungen

Unsere Ergebnisse deuten darauf hin, dass die Testosteronsuppression das kraniofaziale Wachstum während der Pubertät beeinflusst.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Küchler EC, Reis CLB, Carelli J et al (2021) Potential interactions among single nucleotide polymorphisms in bone- and cartilage-related genes in skeletal malocclusions. Orthod Craniofac Res. https://doi.org/10.1111/ocr.12433

Ferguson D, Dean JA (2015) Growth of the face and dental arches. In: Dean JA (ed) McDonald and Avery’s dentistry for the child and adolescent, 1st edn. Elsevier, Moby, pp 375–389

Clarke BL, Khosla S (2009) Androgens and bone. Steroids. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.steroids.2008.10.003

Vanderschueren D, Laurent MR, Claessens F et al (2014) Sex steroid actions in male bone. Endocr Rev. https://doi.org/10.1210/er.2014-1024

Reis CLB, Guerra KCC, Ramirez I, Madalena IR, de Almeida ACP, de Oliveira DSB (2021) Does suppression levels of testosterone have an impact in the craniofacial growth? A systematic review in animal studies. Braz J Dev. https://doi.org/10.34117/bjdv7n7-644

Manolagas SC, O’Brien CA, Almeida M (2013) The role of estrogen and androgen receptors in bone health and disease. Nat Rev Endocrinol. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrendo.2013.179

Mohamad NV, Soelaiman IN, Chin KY (2016) A concise review of testosterone and bone health. Clin Interv Aging. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S115472

Kapur SP, Reddi AH (1989) Influence of testosterone and dihydrotestosterone on bone-matrix induced endochondral bone formation. Calcif Tissue Int. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02556469

Maor G, Segev Y, Phillip M (1999) Testosterone stimulates insulin-like growth factor‑I and insulin-like growth factor-I-receptor gene expression in the mandibular condyle—a model of Endochondral ossification. Endocrinology. https://doi.org/10.1210/endo.140.4.6618

Wu J, Henning P, Sjögren K et al (2019) The androgen receptor is required for maintenance of bone mass in adult male mice. Mol Cell Endocrinol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mce.2018.10.008

Arai KY, Hara T, Nagatsuka T, Kudo C, Tsuchiya S, Nomura Y, Nishiyama T (2017) Postnatal changes and sexual dimorphism in collagen expression in mouse skin. PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0177534

Salonia A, Rastrelli G, Hackett G et al (2019) Paediatric and adult-onset male hypogonadism. Nat Rev Dis Prim. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-019-0087-y

Verdonck A, Gaethofs M, Carels C, de Zegher F (1999) Effect of low-dose testosterone treatment on craniofacial growth in boys with delayed puberty. Eur J Orthod. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejo/21.2.137

Marečková K, Weinbrand Z, Chakravarty MM et al (2011) Testosterone-mediated sex differences in the face shape during adolescence: subjective impressions and objective features. Horm Behav. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yhbeh.2011.09.004

Lefevre CE, Lewis GJ, Perrett DI, Penke L (2013) Telling facial metrics: facial width is associated with testosterone levels in men. Evol Hum Behav. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2013.03.005

Penton-Voak IS, Chen JY (2004) High salivary testosterone is linked to masculine male facial appearance in humans. Evol Hum Behav. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2004.04.003

Whitehouse AJO, Gilani SZ, Shafait F et al (2015) Prenatal testosterone exposure is related to sexually dimorphic facial morphology in adulthood. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2015.1351

Bird BM, Cid Jofré VS, Geniole SN et al (2016) Does the facial width-to-height ratio map onto variability in men’s testosterone concentrations? Evol Hum Behav. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2016.03.004

Hodges-Simeon CR, Hanson Sobraske KN, Samore T, Gurven M, Gaulin SJC (2016) Facial width-to-height ratio (fWHR) is not associated with adolescent testosterone levels. PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0153083

Fujita T, Ohtani J, Shigekawa M et al (2004) Effects of sex hormone disturbances on craniofacial growth in newborn mice. J Dent Res 83:250–254. https://doi.org/10.1177/154405910408300313

Fujita T, Ohtani J, Shigekawa M, Kawata T, Kaku M, Kohno S, Motokawa M, Tohma Y, Tanne K (2006) Influence of sex hormone disturbances on the internal structure of the mandible in newborn mice. Eur J Orthod. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejo/cji093

Verdonck A, De Ridder L, Kühn R, Darras V, Carels C, de Zegher F (1998) Effect of testosterone replacement after neonatal castration on craniofacial growth in rats. Arch Oral Biol. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0003-9969(98)00030-2

Verdonck A, De Ridder L, Verbeke G et al (1998) Comparative effects of neonatal and prepubertal castration on craniofacial growth in rats. Arch Oral Biol. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0003-9969(98)00071-5

Marquez Hernandez RA, Ohtani J, Fujita T et al (2011) Sex hormones receptors play a crucial role in the control of femoral and mandibular growth in newborn mice. Eur J Orthod. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejo/cjq124

Coyotupa J, Parlow AF, Kovacic N (1973) Serum testosterone and dihydrotestosterone levels following orchiectomy in the adult rat. Endocrinology. https://doi.org/10.1210/endo-92-6-1579

Jopek K, Celichowski P, Szyszka M et al (2017) Transcriptome profile of rat adrenal evoked by gonadectomy and testosterone or estradiol replacement. Front Endocrinol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2017.00026

Smith AJ, Clutton RE, Lilley E, Hansen KEA, Brattelid T (2018) PREPARE: guidelines for planning animal research and testing. Lab Anim. https://doi.org/10.1177/0023677217724823

Kilkenny C, Browne W, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG (2011) Animal research: reporting in vivo experiments—the ARRIVE guidelines. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. https://doi.org/10.1038/jcbfm.2010.220

Miot HA (2011) Tamanho da amostra em estudos clínicos e experimentais. J Vasc Bras. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1677-54492011000400001

Koolhaas JM (2010) The laboratory rat. In: Hubrecht R, Kirkwood J (eds) The UFAW handbook on the care and management of laboratory and other research animals, 1st edn. John Wiley & Sons, West Sussex, pp 311–326

Idris AI (2012) Ovariectomy/Orchidectomy in Rodents, pp 545–551 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-61779-415-5_34

Omori MA, Marañón-Vásquez GA, Romualdo PC et al (2020) Effect of ovariectomy on maxilla and mandible dimensions of female rats. Orthod Craniofac Res. https://doi.org/10.1111/ocr.12376

Otto GM, Franklin CL, Clifford CB (2015) Biology and diseases of rats. In: Laboratory animal medicine, 1st edn. Elsevier, Moby, pp 151–207 https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-409527-4.00004-3

Wei X, Thomas N, Hatch NE, Hu M, Liu F (2017) Postnatal craniofacial skeletal development of female C57BL/6NCrl mice. Front Physiol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2017.00697

Montes GS, Junqueira LCU (1991) The use of the Picrosirius-polarization method for the study of the biopathology of collagen. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0074-02761991000700002

Lee VWK, de Kretser DM, Hudson B, Wang C (1975) Variations in serum Fsh, lh and testosterone levels in male rats from birth to sexual maturity. Reproduction. https://doi.org/10.1530/jrf.0.0420121

Handelsman DJ, Spaliviero JA, Scott CD, Baxter RC (1987) Hormonal regulation of the peripubertal surge of insulin-like growth factor‑I in the rat. Endocrinology. https://doi.org/10.1210/endo-120-2-491

You KH, Lee KJ, Lee SH, Baik HS (2010) Three-dimensional computed tomography analysis of mandibular morphology in patients with facial asymmetry and mandibular prognathism. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajodo.2010.04.025

Birlik M, Babacan H, Cevit R, Gürler B (2016) Effect of sex steroids on bone formation in an orthopedically expanded suture in rats. J Orofac Orthop. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00056-016-0021-9

van Oirschot BAJA, Jansen JA, van de Ven CJJM, Geven EJW, Gossen JA (2020) Evaluation of collagen membranes coated with testosterone and alendronate to improve guided bone regeneration in mandibular bone defects in Minipigs. J Oral Maxillofac Res. https://doi.org/10.5037/jomr.2020.11304

Porfírio E, Fanaro GB (2016) Collagen supplementation as a complementary therapy for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis and osteoarthritis: a systematic review. Rev Bras Geriatr Gerontol. https://doi.org/10.1590/1809-9823.2016.14145

de Lara RM, dos Santos MC, Omori MA et al (2021) The role of postnatal estrogen deficiency on cranium dimensions. Clin Oral Invest. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-020-03655-0

Acknowledgements

We thank to Minas Gerais Research Foundation (FAPEMIG) and National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) for their support

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

C.L.B. Reis, M. de Fátima Pereira Madureira, C.L.R. Cunha, W.C.R. Junior, T.H. Araújo, A. Esteves, M.B.S. Stuani, C. Kirschneck, P. Proff, M.A.N. Matsumoto, E.C. Küchler and D. Silva Barroso de Oliveira declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical standards

The Local Ethics Committee in The Use of Animals of the Federal University of Alfenas, Alfenas, Brazil, approved this experiment (protocol: 024/2019). All experimental procedures were previously checked by a veterinarian.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Reis, C.L.B., de Fátima Pereira Madureira, M., Cunha, C.L.R. et al. Testosterone suppression impacts craniofacial growth structures during puberty. J Orofac Orthop 84, 287–297 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00056-021-00373-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00056-021-00373-4