Abstract

Drawing on the neo-institutional notion of organizational fields, we propose the concept of the philanthropic field to conceptualize the geography of giving and the interrelations of benevolent activities across the domains of private, public, and civic sectors. Empirically, we adopt a multi-method approach, including a media analysis of reported acts of giving in the German region of Heilbronn-Franconia, a social network analysis of its regional philanthropic relations, and qualitative interviews with representatives of non-profit organizations, corporations, and public as well as private intermediaries. Based on our analysis, we conclude that the philanthropic field is constituted by diverse actors from all sectors of society who engage in specialization, division of labor, and collaboration. Moreover, practices of giving spread across geographical scales, though the majority of activity concentrates on the local and regional level. We conclude by discussing the potentials and limits of our approach as a means to gain insights into local fields of philanthropy and benevolent action across societal sectors.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Philanthropic field

- donation

- geography of giving

- social network analysis

- charitable activities

- case study

- Baden-Württemberg

Economic geography is a field of research that takes an interest in the spatial diversity of economic activity as well as the specific trajectories along which regional economies evolve, and how these trajectories differ between places and across space. In this chapter, we look at the geography of philanthropy and explore the role of financial giving in regional development. Citizens and wealthy patrons donate, foundations and associations engage in and finance benevolent activities, and private businesses assume social responsibility for regional, national, and global communities. Mainstream philanthropy research has largely been analyzing charitable activities from the perspective of the third sector, and has often pursued actor-specific divisions of research into types of giving organizations, such as charities and foundations, patrons and wealthy individuals, non-governmental organizations, and civic associations. This practice has enabled researchers to explore these specific types of actors in depth, yet it has somehow inhibited an evolving understanding of the playing field, in which all these activities come together, especially in geographical, regional contexts. Therefore, and to overcome the evident boundaries of sectorial segmentation, we propose the concept of the philanthropic field to capture the interdependency and interrelations between all benevolent giving across sectors and among diverse types of actors. In this chapter, we seek to explore what we can learn about philanthropy when taking a relational and geographical perspective of fields.

The aim of this chapter is to shift our view from actors to agency of philanthropic giving, to identify differences in engagement, and to explore patterns of collaboration and labor division among different actors in joint projects. After conceptualizing the notion of the philanthropic field as an analytical framework, we present an in-depth, multi-method case study of the Southern German region of Heilbronn-Franconia. In our analysis, we draw on a detailed multi-year media analysis of published cases of donations and financial giving between regional donors and recipients.Footnote 1 We show that apart from third-sector organizations, private businesses also play a central role as promoters in the region by offering financial support to social, educational, and charitable purposes. In addition, different types of actors collaborate across the analytic boundaries of public, private, and civic sectors, a key insight that remains opaque when only focusing on one type of actor. In Heilbronn-Franconia, for instance, foundations and firms joined financial and human resources to make major projects possible in the field of education. In essence, our empirical case study serves as a showcase of how using the perspective of a philanthropic field emphasizes not the actions of one type of organization, but the interaction of all actors involved in the philanthropic field in a specific regional context. Finally, we are inviting a conversation about the role of philanthropic involvement in regional governance and development.

We begin by developing the concept of the philanthropic field as our analytical framework, and then present our case study including data and methods. The presentation of the findings is organized around four dimensions of the philanthropic field: its morphology, the diversity of actors, the connectivity of giving, and the geography of benevolent activity. We conclude by reassessing the philanthropic field’s potential to capture benevolence and giving in regional societies and by exploring the interrelation between philanthropy and social and economic development of regions.

The Philanthropic Field

Researchers of philanthropy in the social sciences have adopted a broad variety of definitions. We conceive philanthropy as voluntary, charitable, or welfare-oriented action, which takes place through the use of financial means, material resources, or time and without expectation of direct compensation (Acs & Phillips, 2002; Andreoni, 2001; Glückler & Ries, 2012). With this definition, we imply that philanthropic engagement not only applies to nonprofit actors such as foundations or nonprofit associations, but also to those actors who, apart from pursuing their economic goals, also act benevolently or contribute to the public good (Phillips & Jung, 2016; Wiepking & Handy, 2015). Scholars in the interdisciplinary research field of philanthropy have studied organizational diversity and the various practices, mechanisms, and modes of philanthropic involvement as well as its social antecedents and effects (Bekkers & Wiepking, 2011; Brown & Ferris, 2007; Diani, 2013; Diani & Pilati, 2011; Galaskiewicz & Wasserman, 1989; Graddy & Wang, 2009; Herzog & Yang, 2018; Maclean & Harvey, 2016; Marquis, Glynn, & Davis, 2007; Ostrander, 2007).

Many researchers have pursued sectoral perspectives or have focused on individual types of actors and organizations (Bekkers & Wiepking, 2007). Whereas researchers focusing on the antecedents of charitable giving and generosity (Andreoni, 2006; Bekkers & Wiepking, 2011; Havens et al., 2007; Havens & Schervish, 2005; Wiepking & Maas, 2009) examine philanthropic commitment and the willingness of the population to donate, those studying elite philanthropy have a particular focus on wealthy individuals and patronage (Faller & Wiegandt, 2010, 2015; Glückler, Ries, & Schmid, 2010; Hay & Muller, 2014; Kischel, 2009; Ostrower, 1995; Saunders-Hastings, 2018). Researchers studying civil society, the third sector, or nonprofit sector (Anheier, 2005; Anheier & Ben-Ner, 1997; Anheier, Priller, Seibel, & Zimmer, 1997; Anheier & Seibel, 1990; Hammack & Smith, 2018; Powell & Steinberg, 2006; Salamon & Anheier, 1992, 1998; Zimmer & Simsa, 2014) compare and assess the characteristics, activities, development, and national conditions of civil society and nonprofit organizations, often focusing on specific types of organizations such as foundations and associations (Adloff, 2010; Anheier, 2003; Birkhölzer, Klein, Priller, & Zimmer, 2005; Hammack & Smith, 2018; Zimmer, 2007), and on these organizations’ interactions with state and market organizations (Salamon, 1995; Salamon & Toepler, 2015). Recently, scholars have challenged sectoral perspectives (Salamon & Wojciech Sokolowski, 2016) and suggested extending the view, for instance, through concepts of hybridization (Anheier & Krlev, 2014; Evers, 2020).

In addition, Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), Corporate Citizenship (CC), and Corporate Philanthropy approaches have been established to examine social and welfare-oriented activities of economic actors, (Beschorner, 2010; Burt, 1983; Carroll, 1999; Crane, Matten, & Moon, 2010; Galaskiewicz & Burt, 1991; Gautier & Pache, 2015; Henderson & Malani, 2009; Hurd, Mason, & Pinch, 1998; Matten & Crane, 2005; Porter & Kramer, 2006; Schwartz & Carroll, 2003; Wolch & Geiger, 1985). Philanthropic activities are often considered part of the overall concept of CSR or CC (Habisch, Wildner, & Wenzel, 2008; Sasse & Trahan, 2007), whereas some authors do not include philanthropic activities in their definition of CSR because of their distance to the company’s core business (Schneider, 2012). This view is often linked to demands that entrepreneurial social or regional commitment should be wedded to corporate strategy and the corporation’s core (Porter & Kramer, 2002, 2006). Moreover, a number of new approaches have emerged in recent decades, their proponents discussing philanthropy from the angle of efficiency and strategy, economic and market-oriented perspectives, such as venture or creative philanthropy, social entrepreneurship, or philanthrocapitalism (Adloff & Degens, 2017; Anheier & Leat, 2006; Letts, Ryan, & Grossman, 1997; McGoey, 2012, 2014; Moody, 2008; Salamon, 2014).

Although focusing on sectors or organizational types contributes to a differential understanding of groups of actors, it entails the danger of neglecting the entirety of philanthropic engagement and the interaction among the actors in specific social and geographical contexts. Alternatively, network approaches help researchers understand interorganizational relationships and the importance of social capital and the institutional embedding of philanthropic actors (Adloff, 2016; Brown & Ferris, 2007; Burt, 1983; Faulk, Lecy, & McGinnis, 2012; Galaskiewicz & Burt, 1991; Guo & Acar, 2005; Harrow, Jung, & Phillips, 2016; Johnson, Honnold, & Stevens, 2010; Krashinsky, 1997; Letts, 2005; Marquis et al., 2007; see also Chap. 8 by Diani).Footnote 2 Moreover, conducting geographical studies sheds light on the regional dimension of fundraising, the “philanthropy market,” and the formative effect of the community context on philanthropic donor behavior (Wolch & Geiger, 1985; Wolpert & Reiner, 1984). Scholars have found that local contexts and geographical disparities set important conditions for regional variations in philanthropy and giving (Bekkers, 2016; Card, Hallock, & Moretti, 2010; Clerkin, Paarlberg, Christensen, Nesbit, & Tschirhart, 2013; Lengauer & Tödtling, 2010; Wolpert, 1988, 1995) at various geographical scales (Bekkers, 2016, p. 124; Havens & Schervish, 2005; Heinemann, 2010; von Schnurbein & Bethmann, 2010). Cross-national comparison reveals the impact of the political, economic, and social and cultural context on philanthropic giving as well as on the size and scope of the not-for-profit sector (Salamon & Anheier, 1998; Wiepking & Handy, 2015, p. 597)Footnote 3. Those utilizing network approaches have often focused on interrelations between philanthropic organizations at the expense of the role of geography, whereas those conducting geographical studies have put emphasis on regionalizing the activity of actors typically of just one sector at the expense of grasping the connectivity between them and across a broader set of diverse actors.

To overcome the limitations of these approaches, we propose the concept of the philanthropic field (Glückler & Suarsana, 2014). With it, we capture the totality of philanthropic activities, diverse actors, and the interconnection amongst all kinds of benevolent actors and their recipients in a geographical context. We have based the concept of the philanthropic field on institutional theory, in which an organizational field comprises the totality of all organizations that form a “recognizable area of institutional life” (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983, p. 148; Lawrence & Phillips, 2004). The notion of the field exceeds the narrow boundaries of sectors, markets, and networks. First, it exceeds the logic of sectors, which are constituted by homogenous types of organizations that offer similar products or services, by looking at diverse actors from private, public, and civic sectors. Second, it exceeds markets, which are defined by competition and trade, to include cooperation, collaboration, cocreation, solidarity, charity, volunteering, and so forth. Third, it exceeds networks, which are defined by connectivity and cohesion, to emphasize the significance of geography, such as the political, institutional, and cultural specificity of place or the proximity in space.

In analogy to physics, a field is the spatial distribution of a social (rather than physical) force that acts on social actors (rather than physical objects). The fundamental idea to be translated into the context of social science is that the force drives or affects social actors in similar ways yet in varying magnitude. In social life, such a force is found in the institutional pressures on individuals and organizations to gain legitimacy by complying with the expectations held in the respective social community or society. Accordingly, one of the axiomatic conjectures in neo-institutional theory is that those organizations belonging to an organizational field will respond to the institutional pressure with isomorphic conversion into similar organizational forms (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983). Similarly, we conceive the philanthropic field as a spatial distribution of benevolent giving that includes actors being exposed to a common set of institutional expectations for legitimacy and who are involved in the structuring of this phenomenon of philanthropy in a specific geographical context. Consequently, the field does not stop at the boundary of the third sector or nonprofit organization; it also encompasses the benevolent giving of private businesses and public organizations, as well as individual citizens, who together co-constitute the field in their roles as employees or mandated representatives in decision making, or as donors, volunteers, or recipients. In essence, a philanthropic field links the geography of giving with the networks of benevolent activities across the domains of private, public, and civic sectors (Fig. 9.1).

To leverage the concept for empirical analysis, we specify any empirical philanthropic field along four dimensions. First, field composition comprises the location and constitution of the diverse participants who contribute benevolent activity in the field. Second, field activity comprises the sources and magnitude of benevolent giving as well as the diverse uses of philanthropic donations. Third, fieldconnectivity encompasses the interactions and interrelations between benevolent actors in the field, including direct collaboration on large joint projects and the division of labor that emerges from specialization and segmentation into often complementary activities. Fourth, field geography is the regional specificity, spatial reach, and interregional relations in philanthropic activities and cooperation. Together, these four dimensions make up the philanthropic field. One of our central objectives in this chapter is to deploy this concept as an analytical framework for empirical exploration in a case study of philanthropy in the Southern German region of Heilbronn-Franconia.

Case Study: Data and Methods

Study Region

In our case study, we draw on intensive research in the rural region of Heilbronn-Franconia, located in the federal state of Baden-Württemberg, Germany. With a GDP of over €500b, Baden-Württemberg would be number 22 in a world ranking of global economies, with a magnitude of economic output similar to Sweden and Poland. Heilbronn-Franconia is a planning region in the northeast of Baden-Württemberg located between the metropolitan regions of Stuttgart, Nuremberg and Rhine-Neckar. It is the region with the second-fastest economic growth in Germany since 2000 (Glückler, Schmidt, & Wuttke, 2015). Its economic structure is based on an internationally competitive manufacturing industry, a high density of world market leaders, and a nationwide above-average income of the region’s 900,000 inhabitants (Glückler, Punstein, Wuttke, & Kirchner, 2020). In pursuit of an extensive exploration of the composition, activity, connectivity, and geography of the philanthropic field in the region, we adopted a mixed-methods research design with which we combined qualitative and quantitative methods for the collection of primary and secondary empirical observations (Table 9.1). We have based the findings we present in this chapter on empirical work carried out as part of the multiyear research project “Regional Philanthropy and Innovation in Heilbronn-Franken” in 2012.Footnote 4

Identification of Field Actors

To identify the actors contributing to the philanthropic field of Heilbronn-Franconia, we consulted official registries from the Land of Baden-Württemberg on the number of charitable clubs and associations as well as of judicable foundations and associationsFootnote 5 with legal capacity. We then decided to take a more detailed look at the foundations located in the region as well as at other regional field actors, drawing on two sources of primary data collection (Table 9.1). First, we conducted a standardized survey of all the identifiable 186 judicable foundations in the region to get information on organizational characteristics and profiles, yet most importantly to learn about interactions and cooperation with other foundations as well as additional partners in benevolent giving. Because our study met high levels of interest and acceptance, a remarkable number of 98 nonprofit foundations (response rate 52.7%) responded to the survey. Secondly, we carried out 33 qualitative interviews with representatives of foundations, nonprofit associations, private businesses, and public entities to explore additional actors in the field, assess their roles, and understand the diversity of philanthropic practices.

Measure of Field Activity: Donations

We aimed at creating a maximally complete database of philanthropic giving in the region to capture the magnitude, structure, and connectivity ofphilanthropic engagement in the field. In the absence of official statistics and due to the limitations of survey techniques regarding response rates and willingness to declare donations, we conducted a media analysis to capture all “publicized” donations within the region. Of course, not all donations are published—for instance, donors may act discreetly or newspapers may restrict reports as a matter of policy. With our analysis, we have covered all cases of giving between 2004 and 2011 that were published in eight regional daily newspapers, each having partial coverage of selected districts in the region (Fig. 9.2). We used a set of 90 keywords and keyword combinations to search the digital archives of these eight newspapers and screened all individual reports manually to verify the transaction and avoid double counting of transactions in cases of multiple reports. After checking each transaction, we created a database on philanthropic relationships between donors and recipients, including the purpose and the amount of each donation.Footnote 6 The database contains a total of 2,297 cases of charitabledonations and donations between 920 donors and 1,234 beneficiaries, amounting to a sum of 129 million euros. Of course, this database only provides insights into the activities voluntarily published in the press. The results are subject firstly to the selection criteria of the responsible editorial offices of the media involved and secondly to our selection criteria in the course of our research.

Field Composition: Who are the Actors?

The region of Heilbronn-Franconia includes the city of Heilbronn at its core and the four rural districts of Heilbronn, Hohenlohe, Main-Tauber, and Schwäbisch Hall. As a consequence of our multiple-method approach, we identified the following groups of actors who represent the potential for philanthropy in the region: wealthy individuals, charitable associations and foundations (funding/grant making and operative), and private businesses. In addition, we included cooperative and less institutionalized entities such as events and project in the philanthropic field (Table 9.3). Together, these constitute a diverse group of donors and sources of benevolent activity.

First, identifying private wealth in Germany on the ground of public statistics is not without its difficulties. In the mid-1990s, the German government abandoned wealth taxes and the state consequently lost transparency over the magnitude and distribution of private wealth. Today, researchers only have forward projections or surveys of small population samples with which to estimate the magnitude and distribution of private wealth. Rather than looking at the assets, we therefore focus on the flows of income. In aggregate, the region enjoys an above-average per capita income, with a peak in the city of Heilbronn. More specifically—and this one can learn in great detail from the official statistics—the region also hosts a great number of income millionaires. Although the sheer number of 179 income millionaires reflects the mean in the spatial distribution across Germany, the income millionaires in Heilbronn-Franconia were, in aggregate, exceptionally rich: The regional average was about double as high as the German average. These statistics of prosperity resonate with the observation of quite a number of patrons and wealthy individuals who have become known for the civic engagement and benevolent giving in the region.

Second, regarding associational life and organized civil society, we found 5,131 publicly registered clubs and associations, of which 1,200 clubs were registered under the legal status of a charitable club, a status that exempts them from paying corporation tax in return for charitable commitment. Third, apart from the charitable associations, a total of 186 judicable foundations under civil and public law were registered with the Stuttgart Regional Council in 2012. There were also 19,551 legally responsible foundations under civil law alone in Germany and 2,847 in Baden-Württemberg (Bundesverband Deutscher Stiftungen, 2013, pp. 112–114). The responding foundations in Heilbronn-Franconia had relatively larger endowments than the average endowments of all German foundations (Table 9.2). Although one learns little about actual philanthropic activity from the mere number of nonprofit organizations, the structure of household incomes and foundation assets is consistent with a solid financial basis for philanthropic commitment within the region. The majority of the foundations in the survey (71.1%) categorized themselves as funding/grantmaking foundations. A further 20.6% are both operative as well as grant-making, whereas 8.2% pursue only operational activities.

Finally, we observed that the regional population had a remarkable level of involvement with philanthropy and civic engagement. Based on our analyses of the number of organizations and of our foundation survey, we conclude that in addition to 1,200 charitable support clubs and associations with an unspecified number of tens of thousands dedicated members, another approximately 1,400 citizens regularly volunteered on an honorary basis for almost all the regional foundations. Apart from the few hundred people directly involved with a foundation, we counted a total of 252 individuals who acted as members of management or supervisory boards, thus being directly responsible for decisions about their foundation’s activities. Finally, two thirds of all foundations reported sustaining advisory boards with a total of 391 board members who typically share their expertise, experience, prestige, and social networks to leverage the work of a foundation.

Field Activity: What are the Practices of Giving?

Drawing on a detailed analysis of published media reports on donations in the region, we found that the philanthropic commitment in Heilbronn-Franconia had increased significantly between 2004 and 2011. Within this short period of only seven years, the annual number of published transactions more than doubled to over 400. Despite the steady rise of donations, the grant volumes had been volatile over time, with an unprecedented peak in 2010 (€42 million). Despite the relative volatility, there is a trend towards increasingly more donations to beneficiaries. In total, we found donations with an aggregate value of 129 million euros through our media analysis.

The media analysis not only shows that considering only one isolate type of philanthropic donor would be inadequate but also that wealthy individuals and private businesses also play a significant role in philanthropic giving. Charitable foundations accounted for the majority share (61.7%) of all funding volume, with one foundation making up 45.9% of the total sum (€59.37m).Footnote 7 Yet the second most important group of donors were private business firms who accounted for 10.5% of the volume and 20.3% of the number of donations. Excluding private businesses from the perspective of the field would thus leave out a substantial share in overall regional benevolent engagement. When ranked by the volume of donations, wealthy individuals come third. Although individual patrons have a minimal share in the number of transactions, their donations amount to the third largest share of 8.4% in the volumes of money donated. Although clubs and associations are largest in terms of the number of transactions, they fall to only fourth place in terms of the amounts of money donated. This diversity of actors is a significant insight to be gained from a field perspective. Public organizations and entities were the largest recipients, with 55% of the total amount given. Whereas foundations and private businesses together accounted for the lion’s share of 70% of funding, clubs and associations accounted for the highest number of individual transactions (Table 9.3A). The not-for-profit sector received the largest flow of donations, comprising a total of 94.6 million euros, that is, 73.2% of the total amount of all grants. Cooperation between for-profit and not-for-profit organizations received the second largest share (€34.5 million, 26.7%) (Table 9.3B).

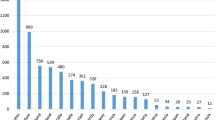

One of the fundamental advantages of building a transaction database by using media reports is that we could carefully read every news article and thus extract more detailed information on the donors, beneficiaries, and donation purpose. Hence, we were able to distinguish a variety of different purposes, ranging from the most popular purposes of “education, academia, and research” and “charity and humanitarian aid” to more niche purposes such as “leisure,” “environment and animal care,” or even “economy” (Table 9.4). The distribution of donations across the many purposes was highly skewed. The greatest number of donations fell in the area of charity and humanitarian aid, which represents the classic destination of philanthropic support. In total, over 1,000 donations, corresponding to almost half of all transactions, were dedicated to his purpose, yet these transactions represent only 18.3% of the volume of donated money. In turn, whereas education, academia, and research received only 17.8% of the number of donations, its cumulative value amounted to almost 81 million euros and made up 62.6% of the volume of donated assets. These figures may reflect a recent trend that education has become an increasingly popular target of philanthropy (Glückler & Ries, 2012), but also reflects the impact of the largest regional foundation, with its focus on education, that was responsible for 59,273,500 euros of the total amount given.

Field connectivity: How Does Giving Create a Network of Cooperation?

The third dimension of connectivity is used to focus on the network of giving as well as the divisions of labor and interactions among donor organizations in terms of collaboration in philanthropic projects as well as across the traditional nonprofit and for-profit sectors.

Regarding field connectivity, we analyzed the topology of the transactional network generated by the aggregate of philanthropic donations. In our media analysis, we retrieved 920 donors who made 2,297 donations to 1,234 recipients worth over 129 million euros. Because some of the donors were nonidentifiable, we were able to include a slightly reduced number of 789 donors and 1,103 recipients in our socialnetwork analysis, amounting to a total volume of 93.4 million euros. Bilateral and nonrecurring donor-recipient relationships dominate the network. The main component includes 62% of the actors, 75% of the relations, and 42% of the aggregate grant value (Fig. 9.3). A small patronage elite faces a broad civic commitment. The small number of large donations is offset by a large number of small donations. The median donation is less than 2,500 euros. Using more detailed techniques of network analysis (Glückler & Panitz, 2021), such as a triadic census, we revealed that giving is spread widely across the field and does not tend to cluster very much. Donors mostly supported several beneficiaries, whereas beneficiaries tended to receive grants from the same donors.

Although the endowments, objectives, and strategies of public, private, and civic organizations differ, we expect all these types of actors to shape and influence their philanthropic activities together and to be interrelated in the philanthropic field (Glückler & Ries, 2012). From a geographical perspective, therefore, questions arise about their interaction and possible forms of complementarity, specialization, and cooperation between them with a view to achieving benevolent goals in a philanthropic field. We draw on the notion of the value chain to distinguish different stages of involvement in the chain of giving, ranging from original donations and financial support, the collection of assets in funding organizations, and operational activities to the final recipients. The stages of individual giving, organizational fundraising, and operational charity are complemented and interlinked by intermediary actors (e.g., public entities, authorities, organized events, interest groups) and supported by cooperation partners, for example by syndicated donations or operational collaboration among operational foundations (Fig. 9.4).

Although the donation network we drew from the media reports comprises a large number of financial donations, it does not include the specialization and collaboration between the different actors in the division of philanthropic giving. To obtain additional information on these relations, we carried out a survey of all 186 judicable foundations registered with the regional council in Stuttgart. With this survey, we focused on how foundations had specialized on certain stages and collaborated with other partners in the provision of philanthropic giving. With 98 charitable foundations taking part, we achieved a response rate of 52.7% of the entire regional population of foundations. More than half of the questionnaires were completed by a board member; in one third of cases the managing director answered. With this survey, we learned that 71% of the foundations acted exclusively as sponsors—that is, they only donated money for charitable purposes—whereas 20.6% engaged in both funding and their own project operations, and a minor share of 8.2% exclusively pursued operational activities, depending on financial support from other organizational and individual donations.

This pattern of specialization reflects the contours of horizontal and vertical divisions of labor, in which operationalfoundations seek and receive donations from sponsoring organizations that are concentrated on fundraising, including from individual donors and citizens. In the horizontal dimension of the chain of giving, two types of cooperation emerged from the survey. First, 71% of surveyed foundations stated that cooperation with partners consisted of co-financing common charitable purposes and projects. Another 49% reported practices of co-operation in that they worked together with partners to develop themes and topics, and 38% of the charities even reported actively collaborating on joint projects. Most foundations agreed that cooperating more extensively with other foundations would increase the efficiency of charitable work. However, more than half of the surveyed foundations stated that they did not cooperate with partners. In contrast, a large proportion of foundations in the survey reported cooperation across sectors, including public, private, and other nonprofit organizations as important cooperation partners. The most frequent cooperation partners were public entities, named by 27 foundations, followed by associations and private businesses. In most cases, the cooperation developed through existing personal contacts. Nevertheless, a quarter of surveyed foundations confirmed that they were also actively seeking new partners.

In the vertical dimension of the chain of giving, we learned from our survey that funding relationships largely exist between not-for-profit actors. The majority of the foundations were tied up in fixed funding relationships with both donors and recipients. This pattern of linkages appeared to be quite stable and rather inert, reflecting long-term established channels of philanthropy. On the one hand, these established channels guaranteed continuous dedication to the same purposes and recipients; on the other, this rigidity incurred problems for those foundations that aimed to access new donors to expand their activities. Overall, the region’s foundations desired better access to and more visibility vis-à-vis potential sponsors. Moreover, they reported that they were less visible to potential donors and multipliers than to recipients. From several interviews, we discovered the relevance of connectivity and formal as well as informal relations between regional actors for philanthropic practices, with personal relations bridging gaps between organizational logics of action. A representative of a regional business firm, associated with a charitable foundation, characterized the regional division of labor among the regional foundations and their relations with regional philanthropists:

We were in conversation with [Philanthropist A] very often and he asked: “What shall we do together?” He is also strongly connected within the region, and we are now working very closely together with our foundations…. We work together locally, where there is no competition. [Philanthropist B], he says he works on the topic “children,” and then we stay out of that. Because there is no use if we do that as well. (Representative, business firm C)

The activities of business firms, foundations and other charitable and public actors were intertwined in many different ways: The degree of cooperation among foundations and between foundations and public and private businesses varied widely. The surveyed foundationsreported a stronger interest in forms of cooperative regional involvement than business firms. In our set of qualitative interviews with selected business representatives, interviewees conveyed that sufficient local possibilities for funding existed. We learned from the discussions that businesses had their philanthropic strategies well defined and that they counted on sufficient regional and local cooperation opportunities through personal and organizational networks. In turn, foundations were particularly interested in new, creative forms of cooperation, such as opportunities for short-term project collaboration. They also welcomed the idea of cooperation being orchestrated by intermediaries who could provide support in finding partners, initiating cooperation, or forming consortia for joint funding. Furthermore, some foundations emphasized the social benefit of a stronger pooling of funds in order to enable joint funding offers that small or individual foundations could not provide. However, not all foundations were so open to additional cooperation. For example, interviewees feared the resources required to establish new cooperations and the loss of organizational independence.

Despite the independence of most philanthropic actors, several large charitable projects had been realized in the Heilbronn-Franconia region, projects characterized by the cooperative interaction of business firms, foundations, and other actors. One showcase of the complex pattern of intersectorial collaboration among a diverse group of actors is the regional Pakt Zukunft [pact for future].

The Pakt ZukunftHeilbronn-Franken was founded in 2007 by regional stakeholders as a partnership with the purpose of jointly representing regional interests. A total of 134 municipalities, private businesses, and civic organizations participated in this initiative and met regularly for network meetings, lectures, and working groups. At the same time, the Chamber of Industry and Commerce (IHK) established the nonprofit enterprise Pakt ZukunftHeilbronn-Franken gGmbH to raise money from the largest corporations in the region and to fund charitable projects in the region. The purpose was to promote the overall well-being of the Heilbronn-Franconia region, especially in the areas of education and upbringing, youth and elderly care, and science and research. Three years later, in 2010, the pact failed, and members withdrew from the original organizational structure. However, the shareholders of the nonprofit enterprise relied on their growing solidarity and interest in continuing joint activities within the framework of Corporate Social Responsibility. From then on, the participating business firms concentrated on financially supporting nonprofit projects in the region. Since 2011, when a leading automotive manufacturer joined the enterprise as a shareholder, Pakt Zukunft supported more than 40 regional projects with an increasing focus on education and science. Interview partners emphasized several factors of the successful establishment and co-operation in the Pakt Zukunft enterprise. First, the initiative is built on existing personal relationships and trust, which provided the glue and confidence to engage in joint financial cooperation. Second, the initiative benefited from the opportunity for a number of regional entrepreneurs to become more involved in their region, actors who thus responded gratefully to such an inclusive nonprofit initiative. Third, the shareholders appreciated the serious framework in order to jointly promote more experimental projects in fields requiring action in the longer term. If merely entrepreneurial commitment had been involved, there would have been a risk of attracting negative attention. Fourth, the Pakt Zukunft partners acknowledged the Chamber of Commerce’s central role as a trustworthy intermediary who offered an impartial, serious, and reliable framework needed for project sponsors and funding recipients to be able to balance competing interests. In addition, using the Chamber of Commerce’s existing infrastructure for administration and communication provided additional advantages and prevented the implementation of unnecessary infrastructure:

“Lernende Region Heilbronn-Franken e.V.” [Learning Region, charitable association] and “Pakt Zukunft”: These are cooperations that fortunately are set up, controlled, and supervised by the IHK [regional chamber of industry and commerce]. In order to achieve an effect, the companies in the region really join forces in order to advance such significantly larger projects. That, of course, suits us very well. We don’t have so many employees here on site that we can now run such larger projects ourselves and look after them sustainably. This really is an institution. And the associations that are behind it are very valuable to really make this an investment for us that is pursued consistently and does not have a one-time character. (Business firm representative B)

Field Geography: How Does Geography Shape Philanthropy?

Finally, we examine the geographical dimension as the fourth element of the philanthropic field. Specifically, we assess the extent to which geography makes a difference for the way that philanthropy works. Social commitment is often synonymous with local commitment. Most transactions took place locally within a county (61.8%) and were dedicated to the immediate local environment within a district or the city of Heilbronn. All types of donors focused on the local level as the geographic focus of philanthropic grant relationships between donors and recipients. This finding is consistent with earlier studies on the geography of philanthropy (Wolpert, 1988; Wolpert & Reiner, 1984). Business firms, foundations, and other organizations such as associations, federations, service clubs, and the like directed at least 80% of their activities and financial resources to recipients within the region (Table 9.5).

Whereas most donations were made locally, the largest amount of funding, constituting less than a third of transactions, was directed at the regional level. Only 17.7% of all transactions, but 42.7% of the total volume, crossed a district border within the region.

The region is divided into four areas: Heilbronn, Hohenlohe, Main-Tauber, and Schwäbisch Hall. Because these areas maintain only limited social and economic exchange with each other, we found the probability of a philanthropic relationship between two actors from different districts within the region to be no greater than that with actors outside the region. One donor located in the city of Heilbronn district accounted for 92.5% of grants for the city of Heilbronn and 97.3% of grants for other regions in Germany (Fig. 9.5).

Regarding interregional philanthropic relations, we observed a negative balance: 29.5% of the funds, mostly in the form of large donations, but only 14% of all transactions, went to beneficiaries outside the region. Only 6.9% of donations came into the Heilbronn-Franconia region from outside (Table 9.6).

In addition to geographical diversification, there were also differences in the governance of the commitment—from simple donor-recipient relationships and multilateral divisions of labor between business firms and corporate foundations or foundations with associated support associations, to complex interorganizational associations, such as the Pakt ZukunftHeilbronn Franken gGmbH (see previous section). Further, the geography of giving varied by the type of donor. Business firms used a significantly higher proportion of their funds than foundations at the regional level (Glückler & Suarsana, 2014). In spite of the large number of transactions, they committed only 21.6% of their funds to the local level. Instead, they directed almost half of all funds (47.5%) to recipients at the regional level, that is, beyond their own administrative district within the broader region. In contrast, foundations directed more than half of their financialdonations to beneficiaries in their direct local surroundings. Although the foundations recorded a similar number of grant cases at the regional level, they supported recipients at the regional level with only just under 8% of funds. Business firms’ stronger focus on the regional level reflects a more diversified philanthropic commitment. For example, firms at the local level appeared to be using smaller amounts of money, whereas at the regional level they provided significantly larger financial support. A greater diversification of corporate philanthropy was also reflected in a higher number of activities corporations directed from the region to the national or international level (Table 9.6). In contrast to the geographical diversification of private donations, foundations were often statutorily bound to local purposes or local organizations (e.g., schools) as target groups. This is also reflected in the results of our foundation survey, from which we gleaned that more than 80% of foundations had their geographical focus within the study region, and half alone within their respective municipalities. Overall, this finding supports the assessment of previous studies’ researchers that “most foundations operate primarily at the local or regional level” (Anheier, 2003, p. 70).

In addition, through our interviews with representatives of business and foundations we captured the diversity and different significance of the geographical reference levels for pursuing different strategic goals. The interviewed businesses pursued combinations of local, regional, and national activities. They aimed their local commitment at gaining acceptance and improving the quality of the local environment. Business firms were committed to ensuring good relations in the local environment, including a prosperous and attractive labor market. Locally rooted entrepreneurs said they wanted to “give back” to their home region and combine generosity with economic interest:

And that is really the core belief of [the philanthropist and corporate owner] that it is his job to not only to look after the company, but also to look after this region. And not only out of gratitude and goodwill, to a certain extent you also have to look at it from the perspective of agglomeration, it influences the environment in which he wants to continue to be successful as an entrepreneur in the future. (Business firm representative B)

In contrast, nationwide commitment tended to raise the visibility of CSR activities. This relates to the different logics of the action of market-oriented corporations on the one hand and nonprofit organizations such as charitable foundations on the other—differences that researchers must accountFootnote 8 for in an integrated analysis of a regional philanthropic field. Differences became apparent in the three dimensions: organizational purpose, finance, and flexibility.

First, regarding the organizational purpose: From their legal form and profit orientation as well as their market and economic-success-oriented logic of action, one can conclude that a business firm’s philanthropic activities are linked to direct and indirect benefit expectations, such as positive reputation, employee recruitment, and so forth (Hiß, 2006; Maaß, 2009, pp. 27–28). In contrast, foundations—though these may also seek legitimacy and public awareness—are constituted by formal statutes and the requirements of charitable law for achieving charitable goals. Footnote 9

Second, with respect to finance, business firms cover philanthropic donations with their profits. Due to the earnings expectations of investors and employees, business firms face opportunity costs and are thus pressured to justify activities in the public interest. The philanthropic commitment of firms, therefore, must always be traded off against alternative forms of profit placement. In contrast, foundations are not faced with the question of alternative uses of financial resources for private economic purposes due to their statutory obligation to promote public-interest objectives. However, because foundations are bound to their income from the existing foundation assets, they are dependent either on additional donations or the increase of the foundation assets through endowments or other incoming funds. In this respect, it is to be expected that foundations tend to seek relationships with institutional and individual donors or partners if they wish to expand their funding performance.

Third, business firms are more flexible in their behavior than foundations because they set their goals, strategies, and agendas internally. Although a CSR strategy adopted and communicated in the long term can have a binding effect on future activities, firms can always adapt and change objectives and practices if necessary or if corporate objectives change. On the other hand, foundations have less freedom of choice and flexibility with regard to their commitment, the topics dealt with, and the target group of beneficiaries, due to the statutes’ binding nature and the requirements of nonprofit law. It can therefore be assumed that business firms can firstly show greater adaptability to new needs of charitable support and secondly promote the diversity of these social needs with greater flexibility.

The philanthropic activities of the firms, foundations, and other local actors we covered in fieldwork were all affected by social and spatial proximity between organization representatives, benevolent individuals, and beneficiaries. In choosing topics and projects, they followed locally perceived needs and opportunities to realize local projects together with local partners, to whom again often long-term relations existed beforehand. Existing personal relations, successful cooperation across sectors in the past, and the integration into local associations and networks were referred to as opportunities for the acquisition of partners and donors and as a place where new projects and ideas were developed. From these interviews, we can underline the specific nature of the regional context and unique conditions for the regional philanthropic field.

Conclusion: Strategizing the Philanthropic Field?

We have proposed the philanthropic field as an analytical framework to conceive and capture the interrelations of benevolent activities across the domains of private, public, and civic sectors in a geographical context. The concept of the philanthropic field offers a comprehensive view of philanthropic engagement beyond the sectoral boundaries of civic, public, and private actors.

Through our exploratory case study of the Southern German region of Heilbronn Franconia, we have illustrated that its philanthropic field was territorially constrained, loosely connected, and fragmented, as well as highly diversified in terms of its actors, and with a certain division of labor between them. Through interviews we uncovered close associations between local key actors in the field of philanthropy and the influence of their networks on the selection of recipients, flows of donations, and their willingness to cooperate on the local or regional level.

Moreover, through the field perspective and the use of methods of network analysis we have conveyed that different actors collaborate on big projects that none of the individual actors could have pursued or realized separately. In this way, regional philanthropy has had a considerable impact on education and knowledge creation in Heilbronn-Franconia. The largest share of all donations we covered in our analysis was directed towards science and education and led to the establishment of an entirely new university campus in the region. The vast majority of foundations reported that they had contributed to the creation of new ideas and concepts in other areas of societal development, such as cultural heritage, education, sports, religious practices, and so forth.

Overall, we have used our analysis of the geography of giving in the Heilbronn-Franconia region through the lens of the philanthropic field to show that not only the isolated work of diverse sets of actors, but also the collaborative engagement and interaction of partners from the first (state), second (business), and third sector (civil society) can produce successful contributions to solving social challenges at the regional level. We found both complementary as well as collaborative practices of giving. Coordinated cooperation enables positive economies of scale through the pooling of resources or the combination of complementary competencies. One possible implication for regional development is to include a region’s philanthropic field in processes of regional governance (Glückler et al., 2020), on the one hand in order to promote charitable commitment, but also to orchestrate this commitment more strongly towards public goals and regional development. However, the integration of philanthropy into network governance requires further reflection (Glückler, Herrigel, & Handke, 2020; Jung & Harrow, 2015). Although interviewees named personal contacts and integration into regional networks as positive opportunities for the collaboration between for-profit and not-for-profit activities, we must highlight that individual involvement in local networks may also constrain some agency within the philanthropic field. Conflict- or problem-laden personal relations may quickly constrain the prospect for joint efforts in collaborative philanthropy.

When attempting to use regional commitment as a strategic resource for regional development politicians and planners should respect the individuality of the actors and take into account the diversity of their goals and strategies, as well as their unique combination of field activity and connectivity: In all efforts, it must be acknowledged that social commitment depends on the actors’ regional involvement, self-determination, and initiative (Klein, 2015). Individual organizational or personal goals range from spontaneous or random motives to long-term strategic goals and therefore require broad approaches to governance. Commitment often develops over very long periods of time and within specific contexts. Personal relationships, private initiative, and sympathies and antipathies often determine whether business firms, foundations, municipalities, and other organizations in the various sectors are willing and able to successfully cooperate. External willingness to control and the goal of linking it with strategic regional development may stand in contrast with the philanthropic practices of business firms, foundations, associations, patrons, and volunteers. Recognition of this is a central prerequisite for any regional initiative aiming at the integration of philanthropic involvement in regional development strategies. To use the concept of the philanthropic field is to emphasize the interrelations between the diverse actors and may thus help regional stakeholders to discover new linkages and to initiate new forms of cooperation in pursuit of realizing large projects.

Notes

- 1.

- 2.

In his reflection on philanthropy, Adloff (2016, p. 66) argues that philanthropy “takes place within specific social contexts. […] Interaction on the level of face-to-face contacts must also be taken into account, as well as cultural, social, and institutional frameworks.”

- 3.

Bekkers and Wiepking (2011, pp. 927−943) identified as mechanisms driving charitable giving on the household and individual level: “(1) awareness of need; (2) solicitation; (3) costs and benefits; (4) altruism; (5) reputation; (6) psychological benefits; (7) values; (8) efficacy.” Wiepking and Handy (2015, pp. 610−611) identified eight common facilitating factors for philanthropy, including “1. a culture of philanthropy; 2. public trust, issues of transparency, accountability and effectiveness; 3. regulatory and legislative frameworks; 4. fiscal incentives; 5. the state of the nonprofit sector; 6. political and economic stability or growth; 7. population changes; 8. international giving.”

- 4.

For a more detailed discussion of the study design and methods, see Glückler and Suarsana (2013).

- 5.

Registered associations can be retrieved at the local district courts, whereas we collected the number (though not the identity) of charitable associations from the regional tax offices.

- 6.

We recorded activities for which a transfer of financial or physical resources took place or for which we could allocate a monetary value to the grant. With this analysis step one can only draw conclusions about actors whose activities were published in the media. However, given the general opacity of the field of charitable activities, this appears to be one of the few possible ways to capture all philanthropic activities in the region. For a detailed discussion of the conception and a critical evaluation of the method, see Glückler, Ries, and Schmid (2010).

- 7.

When including this regional actor, the maximum increases from 3.5 to 20 million euros and the total funding amount of foundations from 17 to 76.3 million euros. The regional field is therefore divided: One organization with very high annual income on the one hand and a larger number of smaller foundations on the other. If the largest foundation is excluded, the mean amount donated by foundations still exceeds that of companies.

- 8.

The following relates to not-for-profit foundations within the meaning of German nonprofit law and to profit-oriented companies.

- 9.

There are also differences within each sector. Existing research, for example, refers to particular features of the structure of the commitment depending on the size and form of the business firm (Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2007; Fischer, 2007). The differences among foundations must also be pointed out (Hof, 2003), whereas we apply our argument exclusively to nonprofit foundations.

References

Acs, Z. J., & Phillips, R. J. (2002). Entrepreneurship and philanthropy in American capitalism. Small Business Economics, 19, 189–204. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1019635015318

Adloff, F. (2010). Philanthropisches Handeln: Eine historische Soziologie des Stiftens in Deutschland und den USA [Philanthropy: A historical sociology of donating in Germany and the USA]. New York/Frankfurt: Campus.

Adloff, F. (2016). Approaching philanthropy from a social theory perspective. In T. Jung, S. D. Phillips, & J. Harrow (Eds.), The Routledge companion to philanthropy (pp. 56–70). London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315740324

Adloff, F., & Degens, P. (2017). „Muss nur noch kurz die Welt retten.“: Philanthrokapitalismus: Chance oder Risiko? [Just quickly have to save the world: Philanthrocapitalism: Opportunity or risk?]. Forschungsjournal Soziale Bewegungen, 30, 43–55. https://doi.org/10.1515/fjsb-2017-0085

Andreoni, J. (2001). Philanthropy, Economics of. In N. J. Smelser, & P. B. Baltes (Eds.), International encyclopedia of the social & behavioral sciences (pp. 11369–11376). Oxford: Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B0-08-043076-7/02298-1

Andreoni, J. (2006). Philanthropy. In S.-C. Kolm, & J. M. Ythier (Eds.), Handbook of the economics of giving, altruism and reciprocity (Vol. 2, pp. 1201–1269). Handbooks in Economics: Vol. 23. Amsterdam: North-Holland. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1574-0714(06)02018-5

Anheier, H. K. (2003). Das Stiftungswesen in Deutschland: Eine Bestandsaufnahme in Zahlen [The foundation system in Germany: An inventory in numbers]. In Bertelsmann Stiftung (Ed.), Handbuch Stiftungen: Ziele—Projekte—Management—Rechtliche Gestaltung (2nd ed., pp. 43–85). Wiesbaden: Gabler. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-322-90317-4_3

Anheier, H. K. (2005). Nonprofit organizations: Theory, management, policy. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203500927

Anheier, H. K., & Ben-Ner, A. (1997). Economic theories of non-profit organisations: A Voluntas symposium. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 8, 93–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02354188

Anheier, H. K., & Krlev, G. (2014). Welfare regimes, policy reforms, and hybridity. American Behavioral Scientist, 58, 1395–1411. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764214534669

Anheier, H. K., & Leat, D. (2006). Creative philanthropy: Toward a new philanthropy for the twenty-first century. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203030752

Anheier, H. K., Priller, E., Seibel, W., & Zimmer, A. (Eds.). (1997). Der Dritte Sektor in Deutschland: Organisationen zwischen Staat und Markt im gesellschaftlichen Wandel [The third sector in Germany: Organizations between the state and the market in societal change]. Berlin: edition sigma.

Anheier, H. K., & Seibel, W. (1990). The third sector: Comparative studies of nonprofit organizations. De Gruyter Studies in Organization: Vol. 21. Berlin: De Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110868401

Bekkers, R. (2016). Regional differences in philanthropy. In T. Jung, S. D. Phillips, & J. Harrow (Eds.), The Routledge companion to philanthropy (pp. 124–138). London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315740324

Bekkers, R., & Wiepking, P. (2007). Understanding philanthropy: A review of 50 years of theories and research. Retrieved from https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/148194198.pdf

Bekkers, R., & Wiepking, P. (2011). A literature review of empirical studies of philanthropy: Eight mechanisms that drive charitable giving. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 40, 924–973. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764010380927

Bertelsmann Stiftung. (2007). Das gesellschaftliche Engagement von Familienunternehmen: Dokumentation der Ergebnisse einer Unternehmensbefragung [The social commitment of family businesses: Report of the results of a business survey]. Retrieved from https://www.familienunternehmen.de/media/public/pdf/publikationen-studien/studien/Studie_Stiftung_Familienunternehmen_Das-Gesellschaftliche-Engagement-von-Familienunternehmen.pdf

Beschorner, T. (2010). Corporate Social Responsibility und Corporate Citizenship: Theoretische Perspektiven für eine aktive Rolle von Unternehmen [Corporate social responsibility and corporate citizenship: Theoretical perspectives for an active role of companies]. In H. Backhaus-Maul, C. Biedermann, S. Nährlich, & J. Polterauer (Eds.), Corporate Citizenship in Deutschland: Gesellschaftliches Engagement von Unternehmen. Bilanz und Perspektiven (2nd ed., pp. 111–130). Bürgergesellschaft und Demokratie: Vol. 27. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-531-91930-0_5

Birkhölzer, K., Klein, A., Priller, E., & Zimmer, A. (Eds.). (2005). Dritter Sektor/drittes System: Theorie, Funktionswandel und zivilgesellschaftliche Perspektiven [Third sector/third system: Theory, functional change and civil society perspectives]. Bürgergesellschaft und Demokratie: Vol. 20. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-663-05985-1

Brown, E., & Ferris, J. M. (2007). Social capital and philanthropy: An analysis of the impact of social capital on individual giving and volunteering. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 36, 85–99. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764006293178

Bundesverband Deutscher Stiftungen. (2012). Stiftungen und Vermögen in Klassen: Stand 31.12.2012. [Classification of foundations and private wealth: As of 31.12.2012.]. Retrieved April 1, 2013, from http://www.stiftungen.org/fileadmin/bvds/de/Presse/Grafiken_Zahlen_Daten/Stiftungsvermoegen_Klassen_2012.pdf

Bundesverband Deutscher Stiftungen (Ed.). (2013). Stiftungsreport 2013/14: Auftrag Nachhaltigkeit: Wie Stiftungen Wirtschaft und Gemeinwohl verbinden [Foundation report 2013/14: Mission sustainability: How foundations combine business and the common good]. Berlin: Bundesverband Deutscher Stiftungen.

Burt, R. S. (1983). Corporate philanthropy as a cooptive relation. Social Forces, 62, 419–449. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/62.2.419

Card, D., Hallock, K. F., & Moretti, E. (2010). The geography of giving: The effect of corporate headquarters on local charities. Journal of Public Economics, 94, 222–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2009.11.010

Carroll, A. B. (1999). Corporate social responsibility: Evolution of a definitional construct. Business & Society, 38, 268–295. https://doi.org/10.1177/000765039903800303

Clerkin, R. M., Paarlberg, L. E., Christensen, R. K., Nesbit, R. A., & Tschirhart, M. (2013). Place, time, and philanthropy: Exploring geographic mobility and philanthropic engagement. Public Administration Review, 73, 97–106. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2012.02616.x

Crane, A., Matten, D., & Moon, J. (2010). The emergence of corporate citizenship: Historical development and alternative perspectives. In H. Backhaus-Maul, C. Biedermann, S. Nährlich, & J. Polterauer (Eds.), Corporate Citizenship in Deutschland: Gesellschaftliches Engagement von Unternehmen. Bilanz und Perspektiven (2nd ed., pp. 64–91). Bürgergesellschaft und Demokratie: Vol. 27. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-531-91930-0_3

Diani, M. (2013). Organizational fields and social movement dynamics. In J. van Stekelenburg, C. Roggeband, & B. Klandermans (Eds.), The future of social movement research: Dynamics, mechanisms, and processes (pp. 145–168). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. https://doi.org/10.5749/minnesota/9780816686513.003.0009

Diani, M. (2022). Civil society as networks of issues and associations: The case of food. In L. Suarsana, H. D. Meyer, & J. Glückler (Eds.), Knowledge and civil society (pp. 149–177). Knowledge and Space: Vol. 17. Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-71147-4_8

Diani, M., & Pilati, K. (2011). Interests, identities, and relations: Drawing boundaries in civic organizational fields. Mobilization: An International Quarterly, 16, 265–282. https://doi.org/10.17813/MAIQ.16.3.K301J7N67P472M17

DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48, 147–160. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095101

Evers, A. (2020). Third sector hybrid organisations: Two different approaches. In D. Billis & C. Rochester (Eds.), Handbook on hybrid organisations (pp. 294–310). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781785366116.00027

Faller, B., & Wiegandt, C.-C. (2010). Die geschenkte Stadt: Mäzenatentum in der deutschen Stadtentwicklung [The donated city: Patronage in urban development in Germany]. vhw FWS, 6, 329–336. Retrieved from https://www.vhw.de/fileadmin/user_upload/08_publikationen/verbandszeitschrift/2000_2014/PDF_Dokumente/2010/FWS_6_2010/FWS_6_2010_Faller_Wiegandt.pdf

Faller, B., & Wiegandt, C.-C. (2015). Mäzenatentum in Deutschland: Eine Chance für die Stadtentwicklung [Patronage in Germany: A chance for urban development]? Geographica Helvetica, 70, 315–326. https://doi.org/10.5194/gh-70-315-2015

Faulk, L., Lecy, J. D., & McGinnis, J. (2012). Nonprofit competitive advantage in grant markets: Implications of network embeddedness (Andrew Young School of Policy Studies Research Paper Series No. 13-07). https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2247783

Fischer, R. (2007). Regionales corporate citizenship: Gesellschaftlich engagierte Unternehmen in der Metropolregion Frankfurt-Rhein-Main [Regional corporate citizenship: Socially committed business firms in the Frankfurt-Rhine-Main metropolitan region]. Rhein-Mainische Forschungen: Vol. 127. Frankfurt: Rhein-Mainische Forschung des Instituts für Humangeographie der Johann-Wolfgang-Goethe-Universität.

Galaskiewicz, J., & Burt, R. S. (1991). Interorganization contagion in corporate philanthropy. Administrative Science Quarterly, 36, 88–105. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393431

Galaskiewicz, J., & Wasserman, S. (1989). Mimetic processes within an interorganizational field: An empirical test. Administrative Science Quarterly, 34, 454–479. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393153

Gautier, A., & Pache, A.-C. (2015). Research on corporate philanthropy: A review and assessment. Journal of Business Ethics, 126, 343–369. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1969-7

Glückler, J., Herrigel, G., & Handke, M. (2020). Knowledge for governance. Knowledge and Space: Vol. 15. Cham: Springer.

Glückler, J., & Panitz, R. (2021). Unleashing the potential of relational research: A meta-analysis of network studies in human geography. Progress in Human Geography, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/03091325211002916

Glückler, J., Punstein, A. M., Wuttke, C., & Kirchner, P. (2020). The ‘hourglass’ model: An institutional morphology of rural industrialism in Baden-Württemberg. European Planning Studies, 28, 1554–1574. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2019.1693981

Glückler, J., & Ries, M. (2012). Why being there is not enough: Organized proximity in place-based philanthropy. The Service Industries Journal, 32, 515–529. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2011.596534

Glückler, J., Ries, M., & Schmid, H. (2010). Kreative Ökonomie: Perspektiven schöpferischer Arbeit in der Stadt Heidelberg. [Creative economy: Perspectives of creative work in the city of Heidelberg]. Heidelberger Geographische Arbeiten: Vol. 131. Heidelberg: Geographisches Institut der Universität Heidelberg.

Glückler, J., Schmidt, A. M., & Wuttke, C. (2015). Zwei Erzählungen regionaler Entwicklung in Süddeutschland: Vom Sektorenmodell zum Produktionssystem [Two tales of regional development in Southern Germany: From a sectoral model to the production system]. Zeitschrift für Wirtschaftsgeographie, 59, 171–187. https://doi.org/10.1515/zfw-2015-0303

Glückler, J., & Suarsana, L. (2013). Regionale Philanthropie und Innovation in Heilbronn-Franken: Studie in Kooperation mit der Industrie- und Handelskammer Heilbronn-Franken [Regional philanthropy and innovation in Heilbronn-Franconia: Study in cooperation with the Heilbronn-Franconia Chamber of Commerce and Industry]. Heidelberg: Professur für Wirtschafts- und Sozialgeographie.

Glückler, J., & Suarsana, L. (2014). Unternehmerisches Engagement im philanthropischen Feld: Das Beispiel Heilbronn-Franken [Civic engagement of business firms in the philanthropic field: The example of Heilbronn-Franconia]. Berichte Geographie und Landeskunde, 88(2), 203–221.

Graddy, E., & Wang, L. (2009). Community foundation development and social capital. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 38, 392–412. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764008318609

Guo, C., & Acar, M. (2005). Understanding collaboration among nonprofit organizations: Combining resource dependency, institutional, and network perspectives. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 34, 340–361. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764005275411

Habisch, A., Wildner, M., & Wenzel, F. (2008). Corporate Citizenship (CC) als Bestandteil der Unternehmensstrategie [Corporate citizenship as part of business strategy]. In A. Habisch, R. Schmidpeter, & M. Neureiter (Eds.), Handbuch Corporate Citizenship: Corporate Social Responsibility für Manager (pp. 3–43). Berlin: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-36358-3_1

Hammack, D. C., & Smith, S. R. (Eds.). (2018). American philanthropic foundations: Regional difference and change. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Harrow, J., Jung, T., & Phillips, S. D. (2016). Community foundations: Agility in the duality of foundation and community. In T. Jung, S. D. Phillips, & J. Harrow (Eds.), The Routledge companion to philanthropy (pp. 308–321). London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315740324

Havens, J. J., Hindley, B., McQueen, A., Meisner, M. J., Schervish, P. G., & Trueblood, D. (2007). Geography and giving: The culture of philanthropy in New England and the nation. Boston: Boston Foundation. Retrieved from https://folio.iupui.edu/bitstream/handle/10244/699/GeoGivingReport2007.pdf

Havens, J. J., & Schervish, P. G. (2005). Geography and generosity: Boston and beyond. Boston: Boston Foundation. Retrieved from https://folio.iupui.edu/bitstream/handle/10244/714/Geography%20and%20Generosity%20report.pdf?sequence=2

Hay, I., & Muller, S. (2014). Questioning generosity in the golden age of philanthropy: Towards critical geographies of super-philanthropy. Progress in Human Geography, 38, 635–653. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132513500893

Heinemann, F. (2010). Voluntary giving and economic growth: Time series evidence for the US (ZEW Discussion Paper No. 10-075). https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1695417

Henderson, M. T., & Malani, A. (2009). Corporate philanthropy and the market for altruism. Columbia Law Review, 109, 571–627. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1116797

Herzog, P. S., & Yang, S. (2018). Social networks and charitable giving: Trusting, doing, asking, and alter primacy. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 47, 376–394. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764017746021

Hiß, S. (2006). Warum übernehmen Unternehmen gesellschaftliche Verantwortung? Ein soziologischer Erklärungsversuch [Why do companies take on social responsibility? A sociological attempt at explanation]. Campus Forschung: Vol. 907. New York/Frankfurt: Campus.

Hof, H. (2003). Zur Typologie der Stiftung [On the typology of the foundation]. In Bertelsmann Stiftung (Ed.), Handbuch Stiftungen: Ziele—Projekte—Management—Rechtliche Gestaltung (2nd ed., pp. 765–796). Wiesbaden: Gabler. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-322-90317-4_27

Hurd, H., Mason, C., & Pinch, S. (1998). The geography of corporate philanthropy in the United Kingdom. Environment and Planning C, 16, 3–24. https://doi.org/10.1068/c160003

Johnson, J. A., Honnold, J. A., & Stevens, F. P. (2010). Using social network analysis to enhance nonprofit organizational research capacity: A case study. Journal of Community Practice, 18, 493–512. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705422.2010.519683

Jung, T., & Harrow, J. (2015). New development: Philanthropy in networked governance: Treading with care. Public Money & Management, 35, 47–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2015.986880

Kischel, M. (2009). Das gesellschaftliche Engagement von vermögenden Personen [The social engagement of wealthy people]. In T. Druyen, W. Lauterbach, & M. Grundmann (Eds.), Reichtum und Vermögen: Zur gesellschaftlichen Bedeutung der Reichtums- und Vermögensforschung (pp. 184–199). Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-531-91752-8_14

Klein, A. (2015). Der Eigensinn des Engagements als Voraussetzung guter Engagementpolitik [The self-will of engagement as a prerequisite for good engagement policy]. Forschungsjournal Soziale Bewegungen, 28, 144–149. https://doi.org/10.1515/fjsb-2015-0119

Krashinsky, M. (1997). Stakeholder theories of the non-profit sector: One cut at the economic literature. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 8, 149–161. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02354192

Lawrence, T. B., & Phillips, N. (2004). From Moby Dick to Free Willy: Macro-cultural discourse and institutional entrepreneurship in emerging institutional fields. Organization, 11, 689–711. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508404046457

Lengauer, L., & Tödtling, F. (2010, September 14–17). Regional embeddedness and corporate regional engagement: Evidence from three industries in the Austrian region of Styria. Paper presented at the eighth European Urban & Regional Studies Conference, Vienna, Austria. Retrieved from http://www.dur.ac.uk/resources/geography/conferences/eursc/16-09-10/LengauerandTodtling.pdf

Letts, C. W. (2005). Effective foundation boards: The importance of roles (KSG Working Paper No. RWP05-054). https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.642562

Letts, C. W., Ryan, W. P., & Grossman, A. S. (1997). Virtuous capital: What foundations can learn from venture capitalists. Harvard Business Review, 75(2), 36–44.

Maaß, F. (2009). Kooperative Ansätze im Corporate Citizenship: Erfolgsfaktoren gemeinschaftlichen Bürgerengagements von Unternehmen im deutschen Mittelstand [Cooperative approaches in corporate citizenship: Success factors for joint civic engagement of medium-sized German companies]. Munich: Rainer Hampp.

Maclean, M., & Harvey, C. (2016). “Give it back, George”: Network dynamics in the philanthropic field. Organization Studies, 37, 399–423. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840615613368

Marquis, C., Glynn, M. A., & Davis, G. F. (2007). Community isomorphism and corporate social action. Academy of Management Review, 32, 925–945. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2007.25275683

Matten, D., & Crane, A. (2005). Corporate citizenship: Toward an extended theoretical conceptualization. The Academy of Management Review, 30, 166–179. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2005.15281448

McGoey, L. (2012). Philanthrocapitalism and its critics. Poetics, 40, 185–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2012.02.006

McGoey, L. (2014). The philanthropic state: Market-state hybrids in the philanthrocapitalist turn. Third World Quarterly, 35, 109–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2014.868989

Moody, M. (2008). “Building a culture”: The construction and evolution of venture philanthropy as a new organizational field. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 37, 324–352. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764007310419

Ostrander, S. A. (2007). The growth of donor control: Revisiting the social relations of philanthropy. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 36, 356–372. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764007300386

Ostrower, F. (1995). Why the wealthy give: The culture of elite philanthropy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400821853

Phillips, S. D., & Jung, T. (2016). Introduction: A new ‘new’ philanthropy: From impetus to impact. In T. Jung, S. D. Phillips, & J. Harrow (Eds.), The Routledge companion to philanthropy (pp. 5–34). London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315740324

Porter, M. E., & Kramer, M. R. (2002). The competitive advantage of corporate philanthropy. Harvard Business Review, 80(12), 56–68.

Porter, M. E., & Kramer, M. R. (2006). Strategy and society: The link between competitive advantage and corporate social responsibility. Harvard Business Review, 84(12), 78–92.

Powell, W. W., & Steinberg, R. (Eds.). (2006). The nonprofit sector: A research handbook (2nd ed.). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Salamon, L. M. (1995). Partners in public service: Government-nonprofit relations in the modern welfare state. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Salamon, L. M. (2014). New frontiers of philanthropy: A guide to the new tools and actors reshaping global philanthropy and social investing. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199357543.001.0001

Salamon, L. M., & Anheier, H. K. (1992). In search of the non-profit sector. I: The question of definitions. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 3, 125–151. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01397770

Salamon, L. M., & Anheier, H. K. (1998). Social origins of civil society: Explaining the nonprofit sector cross-nationally. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 9, 213–248. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022058200985

Salamon, L. M., & Toepler, S. (2015). Government-nonprofit cooperation: Anomaly or necessity? VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 26, 2155–2177. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-015-9651-6

Salamon, L. M., & Wojciech Sokolowski, S. (2016). Beyond nonprofits: Re-conceptualizing the third sector. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 27, 1515–1545. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-016-9726-z

Sasse, C. M., & Trahan, R. T. (2007). Rethinking the new corporate philanthropy. Business Horizons, 50, 29–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2006.05.002

Saunders-Hastings, E. (2018). Plutocratic philanthropy. The Journal of Politics, 80, 149–161. https://doi.org/10.1086/694103