Abstract

Objective

Vital statistics to assess surgical care worldwide have been published by the World Health Organization. These data have not been reported for any Latin American country. We sought to measure these metrics as a starting point for understanding how to improve the safety of surgery in El Salvador.

Methods

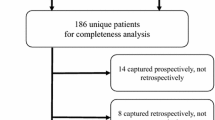

We designed an institutional survey that was sent to 21 hospitals and used national administrative data sources to estimate the number of surgeons, anesthesia professionals, operating rooms, and annual surgical volume for El Salvador. We reviewed surgical and death logs for 12 Ministry of Health hospitals to calculate day-of-surgery and postoperative in-hospital mortality ratios for a 6-month period (October 2009–March 2010).

Findings

We estimate there to be 1,222 surgeons [95 % confidence interval (CI) 1,137–1,307], 539 anesthesia providers, 168 operating rooms (95 % CI 136–199), and 172,972 operations (95 % CI 171,961–173,983) annually in El Salvador. There were on average 1,197 annual cases per operating room and 436 annual cases per surgeon in the 21 hospitals we studied. The day-of-surgery mortality ratio was 0.42 % (95 % CI 0.35–0.5), whereas the postoperative in-hospital mortality ratio was 1.58 % (95 % CI 1.44–1.72). The postoperative in-hospital mortality ratio was higher for hospitals with a greater number of hospital beds (p = 0.01) and operating rooms (p = 0.02).

Conclusions

Despite the challenges that El Salvador faces to provide surgical care, national collection of surgical vital statistics is feasible. Collection of additional process and outcome measures may be insightful for improving the surgical safety in El Salvador and elsewhere.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Weiser TG et al (2008) An estimation of the global volume of surgery: a modelling strategy based on available data. Lancet 372(9633):139–144

Debas HT et al (2006) Surgery. In: Disease control priorities in developing countries, 2nd ed. Oxford University Press, New York

WHO (2008) The top 10 causes of death. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs310/en/index.html. Accessed 5 Feb 2011

Funk LM et al (2010) Global operating theatre distribution and pulse oximetry supply: an estimation from reported data. Lancet 376:1055–1061

Bickler S, Ozgediz D, Gosselin R, Weiser T, Spiegel D, Hsia R, Dunbar P, McQueen K, Jamison D (2010) Key concepts for estimating the burden of surgical conditions and the unmet need for surgical care. World J Surg 34:374–380. doi:10.1007/s00268-009-0261-6

Bickler SW, Spiegel D (2010) Improving surgical care in low- and middle-income countries: a pivotal role for the World Health Organization. World J Surg 34:386–390. doi:10.1007/s00268-009-0273-2

Contini S (2007) Surgery in developing countries: why and how to meet surgical needs worldwide. Acta Biomed 78(1):4–5

Ivers LC et al (2008) Increasing access to surgical services for the poor in rural Haiti: surgery as a public good for public health. World J Surg 32:537–542. doi:10.1007/s00268-008-9527-7

Ozgediz D et al (2009) Bridging the gap between public health and surgery: access to surgical care in low- and middle-income countries. Bull Am Coll Surg 94:14–20

Ozgediz D et al (2009) Population health metrics for surgery: effective coverage of surgical services in low-income and middle-income countries. World J Surg 33:1–5. doi:10.1007/s00268-008-9799-y

Ozgediz D et al (2005) Surgery in developing countries: essential training in residency. Arch Surg 140(8):795–800

Spiegel DA, Gosselin RA (2007) Surgical services in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 370:1013–1015

Ozgediz D et al (2008) The burden of surgical conditions and access to surgical care in low- and middle-income countries. Bull World Health Organ 86(8):646–647

Ozgediz D, Riviello R (2008) The “other” neglected diseases in global public health: surgical conditions in sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS Med 5(6):e121

Sherman L et al (2011) Implementing Liberia’s poverty reduction strategy: an assessment of emergency and essential surgical care. Arch Surg 146(1):35–39

Arreola-Risa C et al (2006) Evaluating trauma care capabilities in Mexico with the World Health Organization’s Guidelines for Essential Trauma Care publication. Rev Panam Salud Publica 19(2):94–103

Kingham TP et al (2009) Quantifying surgical capacity in Sierra Leone: a guide for improving surgical care. Arch Surg 144(2):122–127 (discussion 128)

Weiser TG et al (2009) Standardised metrics for global surgical surveillance. Lancet 374:1113–1117

El Salvador Ministry of Health (2008) Official Report. 380(162):52. http://www.diariooficial.gob.sv/diarios/do-2008/09-septiembre/01-09-2008.pdf. Accessed 5 Feb 2011

Williams DA (1982) Applied statistics, in extra-binomial variation in logistic linear models, 144-148

US Department of State (2010) Background note: El Salvador. http://www.state.gov/r/pa/ei/bgn/2033.htm. Accessed 5 Feb 2011

Gaul K, Ricketts TC III, Walker E, Groves J (2010) Mapping the supply of surgeons in the United States, 2009. American College of Surgeons Health Policy Research Institute, Chapel Hill

Hodges SC et al (2007) Anaesthesia services in developing countries: defining the problems. Anaesthesia 62(1):4–11

Egger Halbeis CB, Schubert A (2008) Staffing the operating room suite: perspectives from Europe and North America on the role of different anesthesia personnel. Anesthesiol Clin 26(4):637–663 vi

Semel ME et al (2012) Rates and patterns of death after surgery in the United States, 1996 and 2006. Surgery 151(2):171–182

Kaiser Family Foundation (2010) TB deaths per 100,000 population. http://www.globalhealthfacts.org/data/topic/map.aspx?ind=19. Accessed Aug 2011

WHO (2009) Global status report on road safety: time for action. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2009/9789241563840_eng.pdf. Accessed 21 Oct 2011

Acknowledgments

This project was funded with a Traveling Fellowship Grant from the Scholars in Medicine Office at Harvard Medical School. The authors thank Dr. Sandra Leal, the President of the Salvadoran Anesthesiology Association, for providing data on the number of anesthesiologists in El Salvador.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Molina, G., Funk, L.M., Rodriguez, V. et al. Evaluation of Surgical Care in El Salvador Using the WHO Surgical Vital Statistics. World J Surg 37, 1227–1235 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-013-1990-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-013-1990-0