Abstract

Although surgical care has not been seen as a priority in the international public health community, surgical disease constitutes a significant portion of the global burden of disease and must urgently be addressed. The experience of the nongovernmental organizations Partners In Health (PIH) and Zanmi Lasante (ZL) in Haiti demonstrates the potential for success of a surgical program in a rural, resource-poor area when services are provided through the public sector, integrated with primary health care services, and provided free of charge to patients who cannot pay. Providing surgical care in resource-constrained settings is an issue of global health equity and must be featured in national and international discussions on the improvement of global health. There are numerous training, funding, and programmatic considerations, several of which are raised by considering the data from Haiti presented here.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction: a coordinated and robust response to the global burden of surgical disease

The burden of surgical disease in the developing world, reflecting a multitude of infectious, noninfectious, and injury-related pathologies, has received inadequate attention to date [1–3]. Among the world’s poorest, a single procedure—amputation—is frequently the definitive therapy for a variety of unrelated processes such as trauma, infection, or gangrene [4]; many die without any care at all. It is increasingly evident that access to surgical services must be rapidly scaled up—in tandem with the development of primary health care infrastructure and programs for maternal and child health and for infectious diseases—to reduce the global burden of disease.

Surgical services in Haiti

Haiti is the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere and is faced, not coincidentally, with the worst health and human development statistics in the region. Inadequate infrastructure and ongoing political instability contribute to high maternal and infant mortality and an average life expectancy of just 53 years [5].

There are three settings in which surgical care is delivered in Haiti. Private hospitals serve major metropolitan areas but have fees that are beyond the reach of the majority of the population. Public hospitals provide surgical care for a smaller fee, but supplies (sutures, medications, intravenous fluids, blood, and even gloves) must be purchased—frequently off-site, at private pharmacies—by the patient before any procedures take place. Charitable organizations are the third category of surgical care providers, but most of these institutions also charge fees for their services. The parallel existence of these three sources of surgical care is typical of most poor countries and, because of attendant fees, does not allow for adequate access to surgical care for the destitute sick—often the very people most in need of services. Among the multitude of nongovernmental organizations operating in rural Haiti, to our knowledge only one, Zanmi Lasante (ZL), provides a permanent setting in which a wide variety of surgical diseases can be addressed free of charge to the patient. This article describes Zanmi Lasante’s experience scaling up surgical services over a 20-year period in a rural, isolated, and resource-poor setting.

Zanmi Lasante: the birth of a “pro-poor” hospital and expansion in the public sector

The Boston-based nonprofit organization Partners In Health (PIH) was founded in 1987 to support community health care efforts launched by ZL in a squatter settlement in central Haiti in 1983 [6]. The hillside site of Cange, originally in the midst of a community displaced by the flooding of a fertile valley for the construction of a hydroelectric dam, is about three hours from the capital city, Port-au-Prince, on a largely unpaved and sometimes impassible road. Since its inception, the medical facility at Cange has grown from a small community clinic to a large sociomedical complex registering more than 250,000 visits annually. Today, l’Hôpital Bon Sauveur in Cange is a 104-bed, full-service hospital with two operating rooms; adult, pediatric, and surgical inpatient wards; an outpatient clinic; an infectious disease unit, which includes the national referral center for the treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR TB); subspecialty services, including women’s health, dental, and ophthalmology clinics; laboratories; pharmacies; a blood bank; radiology services; and a broad range of socioeconomic initiatives. The hospital is linked to a network of hospitals and health centers serving the population of Haiti’s Central and Artibonite Departments, with a combined population of about 1.2 million people.

A critical component of ZL’s growth in this challenging setting is the recruitment and training of community health workers, called accompagnateurs. Today, 2,000 paid accompagnateurs serve as the vital link between ZL’s health facilities and patients dispersed across the rural countryside. Their role in the PIH/ZL model of care, particularly for patients living with HIV or tuberculosis, has been discussed in detail in previous publications [7–10]. A second element of ZL’s growth in Haiti is its engagement with the public health sector to expand access to services. Since 2001, ZL has collaborated with the Haitian Ministry of Health to revitalize and reinforce eight public hospitals and clinics in central Haiti, from rebuilding hospitals to installing generators for electricity, to hiring and training staff, to establishing pharmaceutical supply chains. The explicit goal of this public-private partnership was to leverage funds for AIDS and tuberculosis programs, which became available in 2002, to reinforce comprehensive primary health care and to strengthen health systems in general. Users’ fees, even within the public sector, remained a barrier for the poorest patients until it was agreed that HIV prevention and care, women’s health, TB diagnosis and care, and diagnosis and treatment of all sexually transmitted infections would be considered “public goods for public health”—provided free of charge to the patient [11, 12]. A major consideration for this partnership was the nearly complete absence of surgical services in central Haiti. Could surgical services be considered public goods for public health?

Surgical services at l’Hôpital Bon Sauveur

Although minor procedures, from draining abscesses to tubal ligations, were done intermittently ever since clinical services were first offered in Cange, it was not until 1993 that an operating room was built. With the arrival of a full-time obstetrician-gynecologist, over the next several years the OR was used regularly to address obstetrical emergencies. Short-term medical missions from the United States became increasingly surgical over time, but there were neither general surgeons nor anesthesiologists on staff. As the number of patients seeking care for the major morbidities of TB, HIV, diarrheal disease, and chronic noncommunicable diseases grew, more and more patients with surgical disease also came to l’Hôpital Bon Sauveur seeking care. By the late 1990s, there was increased recognition of the need to treat a variety of routine, urgent, and emergent surgical diseases. To meet these needs, ZL built a second OR and a 15-bed surgical ward, and between 2000 and 2002 hired a general surgeon as well as two additional obstetrician-gynecologists. Through an agreement with the Cuban Ministry of Health, another general surgeon came to the hospital in 2002. An ophthalmologist was hired in 2003 and, with the help of the Haitian Red Cross, a proper blood bank was installed.

By 2005, ZL’s public-private partnerships at small regional hospitals and clinics, along with hundreds of attendant community health workers, served as a network referring patients from across the entire Central Plateau to l’Hôpital Bon Sauveur for evaluation and surgery. Staff at all of the expansion sites are trained in basic surgical resuscitation and stabilization, and referrals are facilitated by Zanmi Lasante/Ministry of Health-owned ambulances in emergency cases or through the provision of transportation stipends to patients with nonurgent problems. Operating rooms at two of the largest expansion sites, Hinche and Belladères, have recently been refurbished and staffed with a full-time obstetrician and nurse anesthetist (NA) for emergency obstetrical care. A Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF)-led NA training program began at l’Hôpital Bon Sauveur in 2006; six nurses from ZL and other parts of Haiti are currently enrolled.

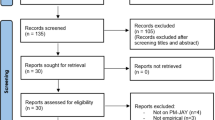

To better understand the volume and variety of surgical procedures at l’Hôpital Bon Sauveur, we undertook a retrospective review of the surgical cases performed between January 2002 and September 2005. We reviewed the operating room logs maintained by the surgical and anesthesia staff for patient age, place of residence, date of procedure, type of procedure, and the specialty involved. Distance traveled to the hospital was estimated as the crow flies based on patients’ place of residence. Table 1 displays the characteristics of surgical patients served at l’Hôpital Bon Sauveur between January 2002 and September 2005. A total of 2,601 patients underwent 2,900 procedures, ranging from simple incision and drainage to complicated cardiothoracic surgeries.

Two notable findings confirmed our experiential understanding of the l’Hôpital Bon Sauveur surgical program. First, the total number of patients seeking services has increased significantly, from 241 patients in 2002 to 762 during the first nine months of 2005. Second, the geographic distribution of patients has expanded: in 2002, more than 80% of patients lived within 50 km of the hospital. By 2005, however, more than half the patients traveled over 50 km to Cange for care—a significant journey to a rural, remote area of the country. This expanding catchment area points to the significance of PIH/ZL’s accompagnateur model, which allows patients who might otherwise not seek care to be identified and referred from their communities and later followed up in their homes as necessary, but also the importance of providing free care to those who need it. By 2005 a third of all patients undergoing surgery at l’Hôpital Bon Sauveur reported their place of residence to be the capital city of Port-au-Prince—the site of the largest public hospital in the country as well as numerous private surgical practices, all of which require fees for services. The widening geographic distribution of the ZL patient base over time presents convincing evidence of the surgical service’s importance not just to the Central Plateau region, where the hospital is located, but to the country as a whole, as cost and/or quality of care are prohibitive factors even when other facilities are available.

A wide variety of surgical pathology was addressed at l’Hôpital Bon Sauveur, with common procedures dominating the census (Table 2). General surgery accounted for almost half (47.6%) of all cases, obstetrical and gynecological cases a third (32.6%) of all cases, and urologic, plastic, neurologic, ophthalmologic, and cardiothoracic cases the remainder. Visiting specialists on short-term missions, largely from the United States, performed operations not normally performed by the staff general surgeons, such as prostatectomy, extraventricular drain placement, and cleft lip repair. One case of mitral valvuloplasty surgery with the use of an extracorporeal bypass circuit was performed by visiting surgeons in 2002.

Discussion: implications for scaling up surgical services in resource-poor settings

What are the primary lessons of what is, in the end, a rather modest attempt to address surgical disease in a setting of great poverty? Other programs are surely larger in terms of volume; indeed, our own infectious disease and primary health care programs, which counted 1.6 million clinical exchanges in 2006, dwarf the surgical program. However, we believe this effort is noteworthy in large part because it provides services to people who would otherwise not have access to them, and for a simple reason: they cannot pay the fees associated with almost all surgical care. In an area in which medical insurance is all but unknown, what would be the financing strategy to manage both elective and emergent surgical services?

Over the years, PIH and ZL have drawn on both the public health and human rights paradigms to help build and keep afloat a surgical program in a setting in which fee-for-service models are doomed to fail. Outside assessments and some members of the ZL staff suggested that certain surgical services could be provided on a sliding payment scale, but even a cursory study of this approach led us to conclude that triaging patients’ ability to pay would have required significant resources and yielded little. It would have cost more to perform such means tests than could be recovered through patient fees. For the destitute sick, the great majority of our patients, the only hope for access to such services came from operationalizing the notion of health care as a human right and maintaining free access to surgical services as we do for medical services [13]. Efforts to keep afloat ZL’s rights-based surgical program proved taxing; by 2003, ZL was seeing patients from around the country, the costs of the program continued to rise, and no foundations or international funding mechanisms existed to support the provision of surgical services—even emergency obstetrics—to the very poorest.

The connection between women’s health and surgical care may well help us to move forward the general surgical agenda in resourced-constrained settings, as we argue in an accompanying editorial [14]. Because there is a strong focus on women’s health in both primary care and HIV services at Zanmi Lasante, it is no surprise that women also constitute the majority (55%) of surgical patients in this review. Although there is to date little enthusiasm for the notion of a right to surgical care, there is a growing movement to promote safe childbirth as a right—a possible entry point for promoting a broader agenda for surgical care in resource-poor settings.

Many challenges remain for ZL to be able to fully address the burden of surgical disease in the Central Plateau and beyond. These challenges are shared in other similarly poor and rural areas worldwide: inadequate basic infrastructure, lack of trained health-care workers, and lack of large-scale, sustained funding for surgical services.

This last issue—the question of consistent funding sources—is one of utmost importance. The logistics and capital costs of setting up a surgical theater are not trivial. Appropriate space, blood-banking, well-trained surgical and postoperative staff, proper tools and supplies, stable electricity, and accessible telecommunications are all essential for high-quality care. The World Bank, among others, has suggested that surgical services incorporated into hospital-level care may be as costeffective as other large-scale public health initiatives [1, 15, 16]. However, large public health initiatives and funders often lack the flexibility and long-term mandate to support the construction of surgical theaters or the regular procurement of consumables, let alone the provision of free care to patients who are unable to afford user fees.

Staffing is a second major challenge. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that more than four million workers are needed worldwide to meet health-care needs, with sub-Saharan Africa and parts of Asia the most understaffed [17]. The dearth of health personnel is even more striking in specialty fields. Shortages in surgical staffing include anesthesiologists, specialist and general surgeons, and nurses trained in postoperative or intensive care. The “brain drain” of workers from low-income to higher-income settings contributes to staffing gaps [18–20]. The AIDS epidemic and its attendant psychological burdens have demoralized health professionals and even further reduced their numbers [21, 22]. Alongside an absolute shortage of health-care workers, the distribution of existing personnel between capital cities and rural areas is severely imbalanced, and encouraging health personnel to live and work in rural areas can be difficult.

In addition to providing sufficient remuneration, ongoing training, and career-development opportunities, ZL has succeeded in retaining surgical staff in part because of the powerful motivator of providing health-care workers with the tools they need to perform their trade—namely, medicines, supplies, and adequate facilities. Targeted, local training efforts can also help overcome staffing shortages. At l’Hôpital Bon Sauveur, the chief of anesthesia is a nurse anesthetist from the area who was one of 19 NAs trained by Médecins Sans Frontières in Haiti between 1998 and 2002. Unfortunately, very few of these graduates are working in the public sector in Haiti; many are not working as NAs at all.

In some cases, visiting staff can effectively supplement in-house capacity. Well-organized, short-term surgical missions can address complicated surgical issues if high-quality follow-up care and services are available after the visiting surgeons leave. Developing residency training programs for U.S. surgeons based in resource-poor settings is one way to accomplish this. We have done this for medical residency [23, 24]; now we need to do it for surgery. In extreme cases, some surgical patients with conditions that cannot be addressed in situ in Haiti have required intervention in the United States. PIH’s Right to Health Care program serves patients with life-threatening medical and surgical needs that cannot be met at l’Hôpital Bon Sauveur or other hospitals in Haiti. Recent interventions have included surgery for repair of tetralogy of Fallot and rheumatic mitral valve disease, total hip replacement, neurosurgery for excision of meningioma, nephrectomy, and plastic surgery management of severe burns.

Conclusion

Surgical disease has been neglected as a serious public health problem despite its major contribution to death and disability worldwide [16]. Half a million women die of pregnancy-related causes every year; leading causes such as hemorrhage and obstructed labor have effective surgical interventions that are simply not available to those who need them most [25]. Annually, more than one million people lose their lives to road traffic accidents, and 875,000 children and adolescents die as a result of injuries such as burns and falls [2]; these pathologies all have surgical therapies that can save lives or prevent disability.

Recently there has been increasing acknowledgment of the importance of surgical care in public health. In 2005, the WHO established the Global Initiative for Emergency and Essential Surgical Care (GIEESC) with the aim of improving collaborations among organizations and agencies involved in reducing morbidity and mortality from surgical conditions [2]. Further discussions have appeared recently in both medical and surgical journals [26, 27], and the second edition of the World Bank’s influential Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries included a chapter on surgery [1]. The Bellagio Conference in June 2007 brought together leaders in surgery, anesthesia, obstetrics, health policy, and health economics from Africa, Europe, and the United States, who collectively concluded that a significant proportion of the global burden of disease is surgical, that with investments in infrastructure and training a majority of surgical disease can be treated or prevented at first-level referral centers, and that the integration of surgical services with primary health care services will be essential for prevention and referral efforts [16]. Zanmi Lasante’s experience providing surgical services in impoverished rural Haiti suggests that these recommendations are urgent and actionable.

References

Debas HT, Gosselin R, McCord C et al (2006) Surgery. In: Jamison DT, Breman JG, Measham AR et al (eds), Disease control priorities in developing countries, 2nd ed. Oxford University Press, New York pp 1245-1260

World Health Organization (2005) WHO meeting towards a Global Initiative for Emergency and Essential Surgical Care (GIEESC), summary report, December 8–9, 2005, Geneva, Switzerland. Available at http://www.who.int/surgery/mission/GIEESC2005_Report.pdf (accessed 8 January 2008)

Bickler SW, Rode H (2002) Surgical services for children in developing countries. Bull World Health Organ 80(10):829–835. Available at http://www.who.int/bulletin/archives/80(10)829.pdf (accessed 10 January 2008)

Yinusa W, Ugbeye ME (2003) Problems of amputation surgery in a developing country. Int Orthop 27(2):121–124

World Bank (2007) Haiti data profile. Available at http://www.devdata.worldbank.org/external/CPProfile.asp?SelectedCountry=HTI&CCODE=HTI&CNAME=Haiti&PTYPE=CP (accessed 10 January 2008)

Farmer P (2006) AIDS and accusation: Haiti and the geography of blame. University of California Press, Berkeley

Farmer P, Léandre F, Mukherjee JS et al (2001) Community-based approaches to HIV treatment in resource-poor settings. Lancet 358(9279):404–409

Farmer P, Léandre F, Mukherjee J et al (2001) Community-based treatment of advanced HIV disease: introducing DOT-HAART (directly observed therapy with highly active antiretroviral therapy). Bull World Health Organ 79(12):1145–1151

Behforouz HL, Farmer PE, Mukherjee JS (2004) From directly observed therapy to accompagnateurs: enhancing AIDS treatment outcomes in Haiti and in Boston. Clin Infect Dis 38(Suppl 5):S429–S436

Mukherjee JS, Ivers L, Léandre F et al (2006) Antiretroviral therapy in resource-poor settings: decreasing barriers to access and promoting adherence. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 43(Suppl 1):S123–S126

Walton DA, Farmer PE, Lambert W et al (2004) Integrated HIV prevention and care strengthens primary health care: lessons from rural Haiti. J Public Health Policy 25(2):137–158

Kim JY, Shakow A, Castro A et al (2003) Tuberculosis control. In: Smith R, Beaglehole R, Woodward D et al (eds), Global public goods for health: health economic and public health perspectives. Oxford University Press for the World Health Organization, New York pp 54–72

Farmer P (1999) Pathologies of power: rethinking health and human rights. Am J Public Health 89(10):1486–1496

Farmer PE, Kim JY (2008) Surgery and global health: a view from beyond the OR. World J Surg 32. doi:10.1007/s00268-9525-9

McCord C, Chowdhury Q (2003) A cost effective small hospital in Bangladesh: what it can mean for emergency obstetric care. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 81(1):83–92

Anon. (2007) Bellagio report: conference on increasing access to surgical services in resource-constrained settings in sub-Saharan Africa, summary report, June 4–8, 2007, Bellagio, Italy. Available at http://www.dcp2.org/file/137/Bellagio%20Report%20-%20Increasing%20Access%20to%20Surgical%20Services.pdf (accessed 22 December 2007)

Samb B, Celletti F, Holloway J et al (2007) Rapid expansion of the health workforce in response to the HIV epidemic. N Engl J Med 357(24):2510–2514

Walton DA, Farmer PE, Dillingham R (2005) Social and cultural factors in tropical medicine: reframing our understanding of disease. In: Guerrant RL, Walker DH, Weller PF (eds) Tropical infectious diseases: principles, pathogens, and practice, 2nd ed. Elsevier, New York pp 26–35

Physicians for Human Rights (2004) An action plan to prevent brain drain: building equitable health systems in Africa. Boston: Physicians for Human Rights. Available at http://www.physiciansforhumanrights.org/library/documents/reports/report-2004-july.pdf (accessed 10 January 2008)

Chen L, Evans T, Anand S et al (2004) Human resources for health: overcoming the crisis. Lancet 364(9449):1984–1990

Ncayiyana D (2004) Doctors and nurses with HIV and AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa. BMJ 329(7466):584–585

Raviola G, Machoki M, Mwaikambo E et al (2002) HIV, disease plague, demoralization and “burnout”: resident experience of the medical profession in Nairobi, Kenya. Cult Med Psychiatry 26(1):55–86

Furin J, Farmer P, Wolf M et al (2006) A novel training model to address health problems in poor and underserved populations. J Health Care Poor Underserved 17(1):17–24

Farmer PE, Furin JJ, Katz JT (2004) Global health equity. Lancet 363(9423):1832

World Health Organization (2005) World health report 2005: making every mother and child count. Available at http://www.who.int/whr/2005/whr2005_en.pdf (accessed 4 January 2008)

Spiegel DA, Gosselin RA (2007) Surgical services in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 370(9592):1013–1015

Duda RB, Hill AG (2006) Surgery in developing countries: should surgery have a role in population-based health care? Bull Am Coll Surg 92(6):12–18, 35

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Ivers, L.C., Garfein, E.S., Augustin, J. et al. Increasing Access to Surgical Services for the Poor in Rural Haiti: Surgery as a Public Good for Public Health. World J Surg 32, 537–542 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-008-9527-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-008-9527-7