Abstract

This genome announcement includes draft genomes from Claviceps purpurea s.lat., including C. arundinis, C. humidiphila and C. cf. spartinae. The draft genomes of Davidsoniella eucalypti, Quambalaria eucalypti and Teratosphaeria destructans, all three important eucalyptus pathogens, are presented. The insect associate Grosmannia galeiformis is also described. The pine pathogen genome of Fusarium circinatum has been assembled into pseudomolecules, based on additional sequence data and by harnessing the known synteny within the Fusarium fujikuroi species complex. This new assembly of the F. circinatum genome provides 12 pseudomolecules that correspond to the haploid chromosome number of F. circinatum. These are comparable to other chromosomal assemblies within the FFSC and will enable more robust genomic comparisons within this species complex.

Similar content being viewed by others

IMA Genome-F 10A

Nine draft genome sequences of Claviceps purpurea s.lat., including C. arundinis, C. humidiphila and C. cf. spartinae

Introduction

Claviceps purpurea (Clavicipitaceae, Hypocreales) is a plant pathogen that infects the flowers of cereal crops and grasses (Poaceae) causing ergot disease. After floral infection by the pathogen, the seeds of grass hosts are replaced with hard, dark fungal resting bodies called sclerotia or ergots. Consumption of grains contaminated with ergots is harmful to human and animal health, causing ergotism, the result of a spectrum of potent mycotoxins known as ergot alkaloids (Lyons et al. 1986, Miles et al. 1996, Scott 2009). These alkaloids have caused significant health, social and economic concerns at different times in history (Fuller 1968, Caporael 1976, Miles et al. 1996, De Groot et al. 1998, Alm 2003), but are also powerful pharmaceuticals for treating various medical conditions (De Groot et al. 1998, Crosignani 2006, Micale et al. 2006). Understanding the genetic diversity of species, their correlated toxin profiles and molecular backgrounds is important for the agricultural and pharmaceutical sectors, and regulatory agencies.

Intraspecific variations in morphology, alkaloid chemistry, genetics, and ecological niches have revealed the existence of several subgroups (Pazoutovä et al. 2000) in C. purpurea s. lat. These groups were later identified as cryptic species based on multi-gene phylogenetic and population genetic analyses, i.e. C. arundinis, C. humidiphila, and C. spartinae (Douhan et al. 2008, Pažoutovä et al. 2015) and recently a few more species from South Africa were described as a part of the species complex (Van der Linde et al. 2016). In Canada, the incidence of ergot diseases in Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba has been increasing since 2002 (Menzies & Turkington 2014). During a recent investigation of ergot fungi in agriculture areas in Canada, we discovered a few more new phylogenetic lineages: two closely related but different from C. spartinae (G3), one close to C. humidiphila, and another two located as basal branches in the C. purpurea s. lat. complex (Fig. 1). Here, we selected representatives of these new and previously designated lineages, sequenced and assembled their genomes. A complete multigene phylogenetic analysis, including a much greater sampling of strains, will be presented in a separate publication.

Sequenced Strains

Claviceps purpurea s.str.

Canada: Saskatchewan: Estavan SK1 49.14 N 102.99 W, isolated from Triticum aestivum, 2000, R. Clear [identified by J. G. Menzies] (LM28 = DAOMC 250647). Czech Republic: Bezdědice, 49.83 N 14.03 E, isolated from Secale cereale, 2003 [identified by S. Pažoutovä] (LM582 = DAOMC 251723 = CCC771 ex-neotype).

Claviceps purpurea s.lat.

Canada: Alberta: North Star 58.53 N 118.12 W, isolated from Bromus inermis, 7 Sep. 1956 [identified by W. P. Campbell] (LM78 = DAOMC 250578); Metiskow, 52.41 N 110.63 W, isolated from Elymus albicans, 7 Sep. 1956 [identified by W. P. Campbell] (LM81 = DAOMC 250581). Quebec: Cote Nord, MRC Minganie, Pointe-Parent, 50.13 N, 61.08 W, isolated from Ammophila sp., 8 Sep. 2015, J. Cayouette & Y. Dalpé (LM458 = DAOMC 251898).

Claviceps cf. spartinae

Canada: Manitoba: Grant’s Field Snowflake 49.05 N 98.66 W, isolated from Phalaris arudinacea, 2014, J. Menzies [identified by M. Liu] (LM218 = DAOMC 251843). Quebec: Maria-Chapdelaine, parc national de la Pointe-Taillon, river du Lac Saint-Jean, 48.67 N 71.87 W, isolated from Ammophila breviligulata, 31 Aug. 2014, J. Cayouette [identified by M. Liu] (LM454 = DAOMC 251845 = DAOM 550246b-specimen).

Claviceps humidiphila

Germany: Bavaria: near Phillipsreuth, 48.86 N 13.68 E, isolated from Dactylis sp., 1998 and S. Pažoutovä (LM576 = DAOMC 251717 = CCC434 ex-epitype).

Claviceps arundinis

Czech Republic: Haklovy Dvory, Stary Vrbensky pond, 49.01 N 14.43 E, isolated from Phragmites australis, 11 Jan. 2008, M. Kolařík (LM583 = DAOMC 251724 = CCC933 ex-type).

Nucleotide Sequence Accession Numbers

The genome data for the nine strains were deposited at DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank under BioProject PRJNA449361. The versions described in this paper are version QERD01000000, QEQW01000000, QEQX01000000, QEQY01000000, QEQZ01000000, QERA01000000, QERB01000000, QERC01000000, QERE01000000. Raw reads were deposited in NCBI SRA (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra) underaccession numberSRP139610.

Materials and Methods

Fungal mycelia and spores were inoculated onto Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA; BD Difco™) by streaking the medium surface in Petri dishes using inoculation loops, to allow the fungus to cover the dish in a short time and incubated for 10 d at 20 °C in the dark. Mycelia of 1–2 dishes were harvested and ground using liquid N2, followed by genomic DNA extraction using a modified cetyltrimethyl ammonium bromide (CTAB) protocol (Doyle & Doyle 1987). The protocol was modified to remove RNA by adding extra RNase and incubating for longer time as follows: (1) after homogenization of ground fungal tissues with 700 µl 2X CTAB, 140 µl RNase Cocktail™ Enzyme Mix (4x recommended volume ratio: 2.5 µl / 50 µl sample; Invitrogen by Thermo Fisher Scientific), and 28 µl RNASE A(4x recommended volume ratio: 1 µl/100 µl sample) was added, and digested for 6–7 h at room temperature. (2) Afterwards, 10 µl Proteinase K (50 µg/µL stock; Fisher Scientific by Thermo Fisher Scientific) was added to the suspension and incubated for 2 h at 55 °C. (3) Before DNA precipitation, another 35ul RNase Cocktail (recommended volume ratio without extra) was added into the supernatant, incubated for 45 min—1 h at room temperature, followed by adding 650 µL CHCl4 and centrifuging at 13 000 rpm for 15 min. Potential RNA contamination in the DNA samples was checked by running the samples on 1 % agarose gels, and determining the 260/280 ratio using NanoDrop 1000 Spectrophotometer v3.8 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) to ensure no RNA was present. gDNA was quantified using Qubit® 2.0 Fluorometer (Invitrogen by Life Technologies).

The extracted gDNAs were normalized to 400 ng and sheared to a 300 bp insert using a Covaris LE220 instrument. The fragmented inserts were used as a template to construct PCR free Libraries with a NxSeq AmpFREE Low DNA Library kit (Lucigen) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Indexed libraries were pooled into two individual pools and sequencing runs were carried on a NextSeq (Illumina; Molecular Technologies Laboratory, Ottawa Research & Development Centre, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada) using 2x150 bp NextSeq Mid Output Reagent Kits (Illumina).

The FastQC software v0.11.5 (https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/) was used to assess the raw read quality. Poor quality data was removed with Trimmomatic v0.36 (Bolger et al. 2014) using the following parameters: HEADCROP:20 SLIDINGWINDOW:4:20 MINLEN:36. The trimmed reads were error corrected with BayesHammer (Nikolenko et al. 2013). De novo genome assembly was performed using SPAdes v3.10.1 (Bankevich et al. 2012) with the mismatch correction step enabled. Contigs shorter than 1000 bp were discarded. QUAST v4.5 program (Gurevich et al. 2013) was used to evaluate assemblies. Corrected reads were mapped back onto the contigs using Bowtie2 v2.0.0 (Langmead & Salzberg 2012). Alignments produced by Bowtie2 in SAM format were converted to sorted BAM format by SAMtools v0.1.19 (Li et al. 2009) and statistics for nucleotide coverage were generated with Qualimap v2.2 (Garcia-Alcalde et al. 2012). To evaluate the completeness of our genome assemblies Universal Single-Copy Orthologs, BUSCO v2 (Simão et al. 2015) was run on the contigs using the fungal database (obd9). Genome annotation was carried out using GeneMark-ES v4.38 (Lomsadze et al. 2005) with the “fungus” option enabled (Ter-Hovhannisyan et al. 2008). Annotations were validated using Genome Annotation Generator (Hall et al. 2014) and tbl2asn (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/tbl2asn2/). All statistics are summarized in Table 1.

To confirm the identities of the strains, DNA sequences of partial elongation factor 1-α gene were extracted from each assembly of nine genomes using Geneious 10.0.9 (Kearse et al. 2012); the fragments were aligned with representative sequences developed by Pažoutovä et al. (2015) and Van der Linde et al. (2016) using MAFFT version 7 (https://mafft.cbrc.jp/alignment/server/) Katoh & Standley 2013. Maximum Parsimony (MP) analyses were performed using PAUP* 4.0b10 (Swofford 2002) with heuristic search of 200 replicates random stepwise addition, bootstrapping of 1000 replicates. Bayesian Inference (Bl) was conducted using Mr Bayes 3.2 (Ronquist et al. 2012), with two independent runs, each sets four chains of 100 000 000 MCMC generation, and 25 % burn-in.

Results and Discussion

The strains sequenced include: two strains of Claviceps purpurea s.str. and C. cf. spartinae, one strain each of C. humidiphila and C. arundinis, and three strains of C. purpurea s.lat. (Table 1, Fig. 1). The genomes were assembled into 1423 to 2321 contigs with a mean assembly size 30.8 Mb ranging from 28.6 Mb to 35.9 Mb. The average GC content was 51.5 %. The N50 ranged from 21.6 kb to 46.6 kb. The assemblies had a BUSCO completeness score ranging from 96.9 % to 98.6 %; the number of gene models ranged from 8410to 9230.

The genome of Claviceps purpurea strain 20.1 (NCBI accession no. CAGA00000000.1) was previously published by (Schardl et al. 2013). They obtained a similar number of contigs (1442), number of gene models (8823), total assembly size (30.9 Mb), N50 (46.5 kb) and GC content (51.6 %), compared to our assemblies, suggesting we obtained reasonable assemblies. However, they additionally ordered contigs into only 191 scaffolds and performed genome annotation. We ran BUSCO on their assembly and obtained a completeness score of 97.6 %. Our aim is to use these sequenced Claviceps genomes to further understand the species diversity, genetic variation, and establish correlations with ergot alkaloid chemical profiles.

IMA Genome-F 10B

Assembling pseudomolecules for the pitch canker pathogen, Fusarium circinatum, utilising additional genome sequence data and synteny within the Fusarium fujikuroi complex

Introduction

Fusarium includes a diverse group of filamentous ascomycetes (Geiser et al. 2013). Many of these fungi cause diseases on economically important plants, with an estimated 80 % of cultivated crops having at least one associated Fusarium disease (Leslie & Summerell 2006). Within the Fusarium fujikuroi species complex (FFSC), more than 50 phylogenetically distinct species have been grouped into three biogeographical clades (O’Donnell et al. 1998, 2000). Fusarium circinatum, residing in the so-called “American clade”, is the causal agent of the disease known as pine pitch canker that damages susceptible Pinus spp. and Pseudotsuga menziesii (Douglas Fir). It has a cosmopolitan distribution and is associated with significant economic losses due to widespread seedling mortality in nurseries as well as the reduction of growth in mature trees due to dieback of infected branches (Gordon et al. 2015).

The importance of this pathogen has justified sequencing its genome (GenBank accession AYJV00000000, version AYJV01000000) (Wingfield et al. 2012). The isolate sequenced, FSP34 (Gordon et al. 1996), has a genetic linkage map available (De Vos et al. 2007) which has been anchored to the genome (De Vos et al. 2014) enabling localization of quantitative trait loci (QTLs) to the genomic sequence data (De Vos et al. 2011, Van Wyk et al. 2018). The draft assembly was 94.8 % complete (Waterhouse et al. 2017), but it included an exorbitant number of contigs (4145) (Wingfield et al. 2012, De Vos et al. 2014) and this limits its use in comparative genomic studies.

The whole genome sequences of other members of the FFSC are available and their genome complement is present in chromosomes. These include Fusarium verticillioides for which the sequences for only 11 chromosomes are available (Ma et al. 2010). This F. verticillioides assembly excludes that for the twelfth and smallest chromosome known to exist in members of the FFSC. This is due to the dispensable nature of this chromosome, with it being strain-specific within the FFSC (Xu et al. 1995, Ma et al. 2010, Wiemann et al. 2013, Van der Nest et al. 2014). In contrast, the whole molecule sequences have been determined for the full complement of the twelve chromosomes for F. fujikuroi (Wiemann et al. 2013). These two species represent two of the three biogeographical clades of the FFSC. Comparisons among them and F. temperatum have shown a significant level of macrosynteny at the genomic sequence level (Wiemann et al. 2013, De Vos et al. 2014). This highlights the fact that the genomic content on chromosomes is highly conserved between various species in the FFSC.

The aim of this study was to improve the available draft assembly of F. circinatum, and assemble it into pseudomolecules that are comparable with the chromosomes of other members of the FFSC. For this purpose, we utilized additional genome sequence information (i.e. mate-pair sequence data) to allow for the scaffolding of contigs. We then exploited the macrosynteny that characterizes the genomes of species within FFSC (Wiemann et al. 2013, De Vos et al. 2014), to orientate and order these scaffolds into twelve pseudomolecules. In this study we present the pseudomolecule assemblies for the full chromosomal complement of F. circinatum. This improved genome assembly will aid in genome-sequence based studies, particularly those involving chromosomal comparisons. Addition of the F. circinatum pseudomolecule complement will furthermore enable comparative studies focusing on genomic synteny and architecture between the three biogeographic clades within the FFSC, as well as more broadly in the genus Fusarium.

Sequenced Strain

USA: California: isol. Monterey pine (Pinus radiata), 1996, T.R. Gordon, A.J. Storer & D. Okamoto (FSP34, MRC7870, CMW51752, PREM 62197-dried culture).

Nucleotide Sequence Accession Number

The improved genome assembly for Fusarium circinatum, generated in this study, has been deposited at DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank under the accession AYJV00000000, version AYJV02000000.

Materials and Methods

Fusarium circinatum was grown on half strength potato dextrose broth (20 % potato dextrose broth w/v) and incubated at 25 °C in the dark on an orbital shaker at 120 rpm. After 7 d, DNA was extracted following the protocol outlined (Möller et al. 1992) and the DNA quality was assessed using a NanoDrop™ Spectrophotometer.

Additional genomic sequence data from F. circinatum isolate FSP34 and a second isolate, KS17, were utilised for scaffolding the original 4145 contig assembly (Wingfield et al. 2012). Isolate KS17 was cultured from infected root tissue of P. radiata nursery seedlings collected from the Western Cape, South Africa in 2005 (Steenkamp et al. 2014). The genomes of F. circinatum isolates FSP34 and KS17 were sequenced using mate-pair libraries (1 kb insert size) by making use of the SOLiD™ V4 technology (Applied Biosystems) at Secqomics (Hungary). In total, 82.45 and 153.95 million mate-pair reads were obtained for the respective isolates. Poor quality reads (below Q20), reads smaller than 36 bp and duplicate reads were removed in CLC Genomics Workbench v.5.1 (CLCbio, Aarhus).

SSPACE v. 2.0 (Boetzer et al. 2011) was utilized to scaffold the pre-assembled contigs of the FSP34 assembly (GenBank accession no. AYJV00000000) (Wingfield et al. 2012), using the trimmed mate-pair data. Default parameters were used, but the minimum number of paired reads linking contigs to form a scaffold was set to 200. The average genome coverage was calculated using the Lander/Waterman equation (number of reads×read length/genome size).

The resulting scaffolds were then assembled into 11 contiguous pseudomolecules (representing the first chromosome 1–11) using F. verticillioides as a reference genome. The scaffolds were ordered and orientated based on BLAST searches (Altschul et al. 1990) against a local database of the F. verticillioides genome (DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank accession number AAIM00000000.2) using CLC Genomics Workbench. To assemble pseudomolecule 12, scaffolds were ordered and orientated to chromosome 12 of F. fujikuroi (Wiemann et al. 2013) and F. temperatum (Wingfield et al. 2015b), as described above. To indicate a break between the various scaffolds comprising a pseudomolecule, 100 N’s were inserted. Synteny maps were generated between the chromosomes of F. verticillioides and F. fujikuroi and the pseudomolecules of F. circinatum using the program MUMmer v. 3.22 (Kurtz et al. 2004).

The assembled genome was annotated using the MAKER annotation pipeline (Cantarel et al. 2008) utilizing Genemark ES (Ter-Hovhannisyan et al. 2008), Augustus (Stanke & Morgenstern 2005), and SNAP (Korf 2004). Manual curation of the predicted annotations was also performed (Wingfield et al. 2012). As additional evidence, genome data from F verticillioides, Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici and F. graminearum (Ma et al. 2010), as well as expressed sequence tag (EST) evidence for F. circinatum (Wingfield et al. 2012) were included.

Results and Discussion

The improved genome assembly for Fusarum circinatum, generated in this study, has been deposited at DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank under accession no. AYJV00000000, version AYJV02000000. The F. circinatum genome was assembled into 585 scaffolds that cumulatively comprised 43 932 912 bases of DNA and had a N50 of 363 633bp. The genome coverage was 273.82x. A GC content of 47.41 % was obtained, which is comparable to other sequenced Fusarium species within the FFSC (Ma et al. 2010, Wingfield et al. 2012, Jeong et al. 2013, Wiemann et al. 2013, Van der Nest et al. 2014, Chiara et al. 2015, Wingfield et al. 2015a, b, Niehaus et al. 2017a, b, Wingfield et al. 2017, Gardiner 2018, Srivastava et al. 2018, Van Wyk et al. 2018, Wingfield et al. 2018). A total of 14 923 genes were predicted to be protein-coding, yielding a gene density of 339.68 open reading frames (orfs) per million base pairs. Phylogenetic analysis of the sequenced genome confirmed the taxonomic identity as F. circinatum (Fig. 2).

Maximum likelihood tree based on partial gene sequences of β-tubulin and translation elongation factor 1-α (Scauflaire et al. 2011, De Vos et al. 2014). Sequence alignments were assembled with MAFFT version 7 (Katoh & Standley 2013). The program jModelTest v 2.1.7 (Guindon & Gascuel 2003, Darribo et al. 2012) was used to determine the best-fit substitution model (TIM2+I+G substitution model) with gamma correction (Tavare 1986). A maximum likelihood (ML) phylogenetic analysis was performed using PhyML v 3.1 (Guindon et al. 2010). Values at branch nodes are the bootstrapping confidence values with those ≥ 85 % shown. The F. circinatum FSP34 isolate used in this study is indicated in bold.

Pseudomolecules, corresponding to each of the 11 chromosomes of F. verticillioides, were constructed in this study. Pseudomolecule 12 was assembled according to synteny observed with chromosome 12 of F. fujikuroi. We managed to genetically anchor 96.97 % (ca. 42.60 Mb) of the F. circinatum scaffolds to these 12 pseudomolecules. These pseudomolecules harbour 99.09 % of the 15 060 genes originally predicted for F. circinatum (Wingfield et al. 2012). Genomic alignments of these 12 pseudomolecules to the corresponding F. verticillioides and F. fujikuroi chromosomes are shown in Fig. 3. These dot-blots are indicative of the observable macrosynteny of Fusarium species within the FFSC.

Conclusions

Resequencing has provided a vastly improved assembly for Fusarium circinatum characterized by fewer and significantly larger scaffolds. By making use of the macrosynteny known to characterize the genomes of FFSC species (Wiemann et al. 2013, De Vos et al. 2014), we were able to join these scaffolds into 12 pseudomolecules that represent the haploid chromosome number of this fungus.

This new assembly of the F. circinatum genome provides a considerably more robust and complete representation of the whole genome sequence of the pathogen, including pseudomolecules that correspond to the twelve chromosomes of F. circinatum. The availability of the sequence for these pseudomolecules will enable future comparative studies at the chromosomal level between/within the three biogeographic clades of the FFSC. In addition, comparisons of chromosomal architecture will expand our knowledge regarding the genomes of species in the FFSC and highlight inter- and intraspecific similarities and differences between them. This would broaden available knowledge regarding the evolution of an important group of plant pathogens.

IMA Genome-F 10C

Draft genome sequence of Quambalaria eucalypti

Introduction

The genus Quambalaria(Quambalariaceae, Microstromatales, Exobasidiomycetes, Basidiomycotina) includes mainly leaf and shoot pathogens of trees belonging to Myrtaceae (De Beer et al. 2006, Pegg et al. 2009). The exceptions to this are Q. coyrecup which is a canker pathogen of marri (Corymbia calophylla) in Western Australia (Paap et al. 2008), and Q. cyanescens which is an opportunistic pathogen of primarily immunocompromised or debilitated humans (Kuan et al. 2015). The latter species is also frequently isolated from galleries of bark beetles infesting hardwoods, although its ecological role in these ecosystems remains enigmatic (Kolarík et al. 2006). Of the leaf and shoot pathogens in the genus, Q. pitereka and Q. eucalypti are most important. Quambalaria pitereka affects Corymbia species in Australia (Pegg et al. 2009) and China (Zhou et al. 2008), while Q. eucalypti causes disease on Eucalyptus spp. in South Africa (Wingfield et al. 1993), Brazil (Alfenas et al. 2001), Uruguay (Perez et al. 2008), Australia (Pegg et al. 2008), and Portugal (Bragança et al. 2015).

Research on species of Quambalariaceae has mostly focussed on their classification and taxonomy (De Beer et al. 2006, Kijpornyongpan and Aime 2017, Paap et al. 2008), as well as their pathogenicity and impact on tree health (Pegg et al. 2009, 2011). However, little is understood about the life-cycle and general biology of these fungi, that are related to the smut fungi and human pathogenic members of Malasseziales (De Beer et al. 2006, Wang et al. 2015b). For example, it is not yet known whether Quambalariaceae have the ability to reproduce sexually, and if so, what the mating system of these fungi encompasses.

Recently the first genome-based studies started exploring pathogenicity factors in Ustilaginomycotina, and although two species in Microstromatales were included in the comparative analyses, no representative of Quambalariaceae was incorporated (Kijpornyongpan et al. 2018). Whole genome sequences have also been shown to be extremely valuable to study mating systems in smut fungi (Que et al. 2014), the Malasseziales (Xu et al. 2007), and the more distantly related Polyporales (James et al. 2013).

The aim of this study was to produce a draft genome sequence of Q. eucalypti. This genome sequence will allow for the exploration and comparative analyses of genes involved in pathogenicity and mating for this pathogen. Here we report the draft genome sequence of isolate CMW1101, an isolate representing the holotype (PREM 51089) of Q. eucalypti.

Sequenced Strain

South Africa: KwaZulu Natal: Kwambonambi, Eucalyptus grandis clone TAG12, May 1987, M.J. Wingfield (CMW1101=CBS118844 ex-holotype isolate; PREM 51089—holotype).

Nucleotide Accession Number

The draft genome sequence of Quambalaria eucalypti has been deposited at GenBank under accession no. PlRRYC00000000. The version presented here is RRYC01000000.

Materials and Methods

Genomic DNA was extracted from cultures grown on Malt Yeast Agar (2 % Malt extract, 0.5 % yeast extract; 2 % agar, Biolab, Midrand, South Africa) using the method described by Duong et al. (2013). The genomic DNA was sent to Macrogen (South Korea), where one pair-end library with 500 bp insert size was prepared and sequenced on Illumina Hiseq 2500 to get 250 bp pair-end reads, aiming for 100 X coverage.

The raw sequencing reads were imported into CLC Genomics Workbench v. 7.5.1 (CLCbio, Aarhus), and default settings were used to both trim the reads for quality and to produce a de novo genome assembly using the trimmed reads. The completeness of the assembly was evaluated using the Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs (BUSCO v. 1.1b1) tool using the Basidiomycota dataset (Simao et al. 2015). The number of protein coding genes was determined using Augustus v. 3.3.2 (Stanke et al. 2008) using pre-optimised species models for Ustilago maydis.

Results and Discussion

The paired end sequencing yielded just over 31 million reads. Assembly of the trimmed reads resulted in 966 contigs, with the largest contig being 225 583 bp, the smallest contig being 449 bp, with an average contig size of 24 384 bp and the N50 value was 62 600 bp. The genome size is estimated at around 23.5 Mb, estimated through the sum of the contig sizes, with a GC content of 60 %. This estimated size is in the larger size range of that reported in Exobasidiomycetes, which typically range from 17 Mb to 19 Mb with the exception of Tilletia caries with a genome size of 29.5 Mb (Konishi 2013, Saika et al. 2014, Toome et al. 2014, Wang et al. 2015a, Kijpornyongpan et al. 2018). BUSCO analysis indicated an assembly completeness of 84.5 %. The assembly contained 1128 complete BUSCOs (1093 complete single- copy BUSCOs, 35 complete and duplicated BUSCOs), 129 fragmented BUSCOs and 78 missing BUSCOs out of a total 1335 BUSCO groups searched. AUGUSTUS predicted 7241 putative protein coding regions. Phylogenetic analysis of sequences from the sequenced genome confirmed the taxonomic identity as Q. eucalypti (Fig. 4). The availability of the Q. eucalypti genome will enable the inclusion of this species as representative for the family Quambalariaceae in comparative studies with other members of the class Exobasidiomycetes. Such studies could focus on topics like the factors involved in pathogenicity, mating, evolution and more.

Phylogram resulting from a ML analyses using RaxML, based on ITS sequences of selected reference sequences representing all species of Quambalaria. The isolate from which the genomic DNA was extracted is indicated in bold type. T = ex-type isolates; NT = Northern Territory; NSW = New South Wales; WA = Western Australia; and QLD = Queensland. Support values at branches resulted from 1000 bootstraps and only values above 75 % are indicated.

IMA Genome-F 10D

Draft genome sequence of the Eucalyptus pathogen Teratosphaeria destructans

Introduction

The genus Teratosphaeria includes numerous economically important tree pathogens of plantation eucalypts in tropical and subtropical areas (Park et al. 2000, Crous et al. 2009, Hunter et al. 2011). The aggressive pathogen T. destructans was initially reported from Indonesia in 1996 (Wingfield et al. 1996), followed by reports from Thailand, Vietnam, East Timor, Laos, China, and, most recently, South Africa (Old et al. 2003, Burgess et al. 2006, Barber et al. 2012, Greyling et al. 2016). It causes leaf, bud and shoot blight disease in one- to three-year-old trees of Eucalyptus camaldulensis, E. grandis and E. urophylla as well as on hybrids of these species (Wingfield et al. 1996, Old et al. 2003, Barber 2004). The rapid spread of T. destructans over large distances has been attributed to the anthropogenic movement of germplasm to establish clonal Eucalyptus nurseries (Andjic et al. 2011).

The discovery of T. destructans on clonal E. grandis × E. urophylla plantations in South Africa, coupled with its reported rapid spread to new areas, makes this pathogen of major concern to the forestry industries of southern African countries (Andjic et al. 2011, Greyling et al. 2016). Similarly, the ability of this pathogen to rapidly invade new areas are also a concern to Australia, where the prospect of T. destructans spreading to native Eucalyptus species could prove catastrophic to Australia’s commercial and natural vegetation (Old et al. 2003). In this study, the genome sequence of a South African isolate of T. destructans is reported. The availability of a complete genome sequence for T. destructans will prove beneficial to studies on the genes and pathways involved in virulence, pathogenicity and sexual reproduction. Such studies will increase our understanding of the biology of this fungus, which is crucial for the development of preventative and control measures for this tree pathogen.

Sequenced Strain

South Africa: Kwa-Zulu Natal: Kwambonambi, isol. Eucalyptus grandis × E. urophylla, Apr. 2015, I. Greyling (CMW 44962, PREM 62207—dried specimen).

Nucleotide Accession Number

The Teratosphaeria destructans Whole Genome Shotgun project has been deposited at DDBJ/ENA/GenBank under accession no. RIBY00000000. The version described in this paperis version RIBY01000000.

Materials and Methods

Teratosphaeria destructans isolate CMW 44962 was obtained from the culture collection (CMW) of the Forestry and Agricultural Biotechnology Institute (FABI) at the University of Pretoria. A single-spore culture was generated (Greyling et al. 2016) and grown on sterile cellophane sheets placed onto MEA+Y plates (malt extract agar; Biolab, South Africa; amended with 0.3 % yeast extract; Oxoid, Basingstoke). After incubation for four weeks at 25 °C, the mycelia were collected and freeze-dried for DNA extraction. Approximately 30 mg of freeze-dried material, three 5 mm glass beads and 13 mg polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP, Sigma Aldrich, Steinheim) were mixed and powdered in a FastPrep FP120 tissue lyzer (Qbiogene, Carlsbad, CA). Subsequently, 650 µl of CTAB extraction buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl, pH8; 25 mM EDTA; 2 M NaCl; 3.5 % CTAB; 2 % SDS), 2 µl of 500 mg/L spermidine (Sigma Aldrich, Steinheim) and 4.5 % (v/v) β-mercaptoethanol were added and the sample was incubated at 60 °C for 20 min. After cooling to room temperature, 1.5 volumes of chloroform:isoamylalcohol (24:1) was added, the sample was mixed and centrifuged for 15 min at 8100 g. The supernatant was re-extracted with 1.5 volumes of chloroform:isoamylalcohol (24:1) and centrifuged for 15 min at 16 300 g. The supernatant was combined with potassium acetate to a final concentration of 1.5 M. After incubation for 30 min at −20 °C, 1.5 volumes of cold isopropanol were added, followed by a 30 min incubation at 24 °C. Thereafter, the sample was centrifuged for 20 min at 16 300 g to collect the DNA which was washed twice with 70 % ethanol. The dried DNA pellet was dissolved in 50 µl low TE (Tris-EDTA) buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Wilmington, NC).

The genomic DNA sample was submitted to the Central Analytical Facilities (CAF) of Stellenbosch University (Stellenbosch, South Africa) for whole genome sequencing using the Ion GeneStudio S5 Next-Generation Sequencer. An Ion 530 chip with a capacity to generate 12 million reads of 600 bp was prepared as per the manufacturer’s instructions. The resulting single reads were trimmed and assembled using SPAdes v. 3.12.0 (Nurk et al. 2013) with k-values of 21, 33, 55, 77, 99 and 127. The completeness of the genome assembly was evaluated using the Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs (BUSCO v. 2.0.1) tool in conjunction with the fungal data set (Simão et al. 2015). Bowtie2 v. 1.1.2 and SAMtools v. 1.5 were used to calculate the average base coverage by mapping the reads back to the genome assembly (Li et al. 2009, Langmead & Salzberg 2012). QUAST v. 5.0.1 (Mikheenko et al. 2018) was used to calculate general genome statistics.

The β-tubulin and elongation factor 1-alpha (EF1-α) gene regions, commonly used for species delineation in Teratosphaeria (Quaedvlieg et al. 2014) were extracted from the T. destructans genome sequence. These sequences, together with previously published sequences (Quaedvlieg et al. 2014, Aylward et al. 2018) sourced from the NCBI database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) were subjected to a “one click” phylogeny analysis using the Phylogeny. fr online tool (Dereeper et al. 2008, 2010). This analysis included a MUSCLE alignment (Edgar 2004) and a Gblocks (Castresana 2000) curation step before phylogenetic analysis was conducted using PhyML (Guindon & Gascuel 2003, Anisimova & Gascuel 2006).

Results and Discussion

The assembly yielded a genome of 32 316 120 bp assembled into 4132 contigs. Of these, 1837 were 500 bp or larger and contained 31.61 Mb of the genome. The genome had a GC content of 51.83 %, a N50 value of 103 119 bases (with the largest contig 398 757 bp in size), and a L50 value of 94 contigs. The average coverage of this assembly was 170x. The genome completeness, as assessed by BUSCO analysis, was 95.86 %, with 278 complete, five fragmented and seven missing BUSCO terms out of the 290 searched.

The genomic sequence of Teratosphaeria destructans reported here is the first published genome sequence for a member of this genus (Fig. 5). Considering its status as an emerging pathogen (Andjic et al. 2011, Greyling et al. 2016, Burgess & Wingfield 2017) the availability of a genome sequence holds various benefits. These include its use in comparative genomic studies between different Teratosphaeria species, many of which are a concern to the global Eucalyptus industry (Hunteret al. 2011). Similar studies have already yielded insight into the factors that determine host range, while also elucidating an arsenal of pathogenic effectors and virulence factors important for the pathogenicity of fungal species (Klosterman et al. 2011, Condon et al. 2013, Zhao et al. 2013, Deng et al. 2017). The availability of a genome sequence also provides the opportunity to develop species-specific microsatellite markers (Gnocato et al. 2017, Rafiei et al. 2018) that would be important for studying invasive populations of this aggressive, emerging tree pathogen.

IMA Genome-F 10E

Draft nuclear genome assembly for Davidsoniella eucalypti

Introduction

The family Ceratocystidaceae includes an ecologically diverse assemblage of fungi currently classified into 11 distinct genera (De Beer et al. 2014, 2017, Mayers et al. 2015, Nel et al. 2018). The best-known of these is Ceratocystis, a genus that includes economically important plant pathogens such the mango and Acacia mangium pathogen C. manginecans (Al Adawi et al. 2013, Tarigan et al. 2011) and the causal agent of cacao wilt C. cacaofunesta (Baker Engelbrecht & Harrington 2005). Species of the genera Endoconidiophora and Thielaviopsis are well known as pathogens of conifers and monocot plants, respectively (Mbenoun et al. 2014, Wingfield et al. 2013). The genera Bretziella and Berkeleyomyces were recently erected to accommodate the casual-agent of oak wilt Br. fagacearum (previously Ceratocystis fagacearum; De Beer et al. 2017) and the multi-host root pathogen Be. basiola (formerly Thielaviopsis basicola; Nel et al. 2018). Many Ceratocystidaceae species rely on flies, picnic beetles, and ambrosia beetles for spread, forming casual associations with these insects (Van Wyk et al. 2013). In contrast, species in the genera Ambrosiella, Meredithiella, and Phialophoropsis form obligate mutualisms with ambrosia beetles of the tribes Xyleborini, Corthylini and Xyloterini, respectively (Mayers et al. 2015). Three asexual species associated with woody substrates are present in Chalaropsis, while members of the genus Huntiella are considered saprobes or weak pathogens, with only a handful of species known to cause sapstain of timber (De Beer et al. 2014). The genus Davidsoniella consists of four species, three of which (D. eucalypti, D. neocaledoniae and D. australis) are present in Australasia, with D. virescens being described from North America (De Beer et al. 2014).

In this study we report a draft nuclear genome assembly for Davidsoniella eucalypti, first isolated from stem wounds on living Eucalyptus species in Australia (Kile et al. 1996). Although able to colonize wounds made in these trees, the fungus causes limited damage and is not considered pathogenic (Kile et al. 1996). In contrast, D. virescens, D. australis, and D. neocaledoniae are all considered plant-pathogens, causing disease on maple trees (Acer spp.), Nothofagus cunninghamii trees (Kile 1993), and Coffea robusta plants (Dadant 1950), respectively.

Davidsoniella eucalypti and D. virescens are the only two species in the genus for which a sexual morph is known (De Beer et al. 2014), although the reproductive strategy between these species differ dramatically—homothallism in D. virescens and heterothallism in D. eucalypti (Harrington et al. 1998). With the genome sequence of D. virescens already published (Wingfield et al. 2015b), the addition of the D. eucalypti genome brings the total number of Davidsoniella sequences to two. This raises the possibility for interesting genomic studies on these two biologically diverse species.

Sequenced Strain

Australia: Victoria: Cabbage Tree Creek, isolated from Eucalyptus sieberi, Aug. 1989, M.J. Dudzinski (CMW 3254, C 639, DAR 70205—dried culture).

Nucleotide Sequence Accession Number

This Whole Genome Shotgun project for Davidsoniella eucalypti isolate CMW 3254 has been deposited at DDBJ/ENA/GenBank under the accession RMBW00000000. The version described in this paper is version RMBW01000000.

Materials and Methods

Davidsoniella eucalypti isolate CMW 3254 was obtained from the culture collection of the Forestry and Agricultural Biotechnology Institute (FABI) and grown on 2 % malt extract agar (MEA: 2 % w/v, Biolab, South Africa) at 25 °C. A 14-d old culture was used for genomic DNA extraction using a previously described phenol-chloroform protocol (Roux et al. 2004). The isolated DNA was submitted to Macrogen (Seoul, Korea) to generate long-read sequences from three cells of the Pacific BioSciences Single-molecule real time (SMRT or PacBio) sequencing platform. This was complemented by a second round of sequencing on the Illumina HiSeq 2500 instrument at Macrogen. For this, a single library with 550 bp insert size was generated and used to produce pair-end reads of 250 bp target length. The DNA for the Illumina sequencing was extracted as described by Duong et al. (2013).

The reads obtained from the three cells of the SMRT sequencing run were concatenated into a single fastq file which was used for read-correction, trimming and assembly using Canu v1.4 and default settings (Koren et al. 2017). The resulting assembly was scaffolded using SSPACE-LongRead with the default settings (Boetzer et al. 2011, Boetzer & Pirovano 2014), using the corrected long-read sequences produced by Canu. The paired-end Illumina reads were imported into the CLC Genomics Workbench v11.0.1 (Qiagen, South Africa) and trimmed using default settings. These trimmed reads were indexed and aligned to the scaffolded, long-read assembly using BWA (Li & Durbin 2009) and SAMtools (Li et al. 2009). The alignment files were used in three rounds of Pilon corrections (Walker et al. 2014) to improve the long-read assembly by correcting single base differences, small insertions/deletions and other mis-assemblies identified in the draft genome assembly. To produce the best version of the assembly, the trimmed Illumina pair-end reads were used by GapFiller (Boetzer & Pirovano 2012) to fill gaps produced in the assembly during the scaffolding process. The draft genome was assessed for completeness using the Benchmarking Universal Single Copy Orthologs tool (BUSCO v 2.0.1) (Simão et al. 2015) and the Ascomycota database. An estimation of the number of protein coding genes in the genome was made by the de novo prediction software AUGUSTUS using the Fusarium graminearum gene models (Keller et al. 2011, Stanke et al. 2006b), while general genome statistics (genome length, GC content, N50, L50 and largest contig size) were calculated using QUAST v5.0.1 (Mikheenko et al. 2018)

The 60S, LSU and MCM7 gene regions were extracted from the genome and, together with these regions from D. eucalypti, D. virescens, D. neocaledoniae, D. australis, Endoconidiophora polonica, and E. laricicola (De Beer et al. 2014) were used for phylogenetic analysis. The datasets were subjected to a “one click” phylogeny analysis at the Phylogeny.fr online tool (Dereeper et al. 2008, 2010) that included a MUSCLE alignment (Edgar 2004) and a Gblocks (Castresana 2000) curation step before phylogenetic analysis was conducted using PhyML (Guindon & Gascuel 2003). Branch support was calculated using the approximate likelihood ratio test (Anisimova & Gascuel 2006).

Results and Discussion

The 41 874 515 bp genome assembly of Davidsoniella eucalypti was present in 1219 contigs of 1000 bp or large, the largest of which was 1 065 836 bp. The genome had a G/C content of 45.93 %, an average coverage of 69x, a N50 value of 230 092 bp and a L50 value of 51. AUGUSTUS predicted 9029 protein coding genes, while BUSCO reported a completeness score of 96.1 %. This was based on the analysis of 1315 orthologs, with 1236 present as complete single copies, 27 as complete duplicated copies, 16 as fragmented copies, and 36 copies absent.

The genome assembly of D. eucalypti differed dramatically from that of the sister-species D. virescens (Fig. 6) (Wingfield et al. 2015b). At 33.6 Mb, the latter genome was 8.3 Mb smaller than that of D. eucalypti. The latter genome is also predicted to encode more proteins (9029 vs. 6953 for D. virescens), although the gene densities were comparable at 207 and 215 genes/Mb for D. virescens and D. eucalypti respectively. It is known that the genome sizes of plant-pathogenic filamentous fungi tend to be larger than those of non-pathogenic relatives, mostly due to the presence of high amounts of repetitive DNA and an expansion of the effector repertoire (Frantzeskakis et al. 2018, Möller & Stukenbrock 2017, Raffaele & Kamoun 2012). Therefore, the larger genome size of the non-pathogenic D. eucalypti as compared to the pathogenic species D. virescens was surprising and warrants further study.

A maximum-likelihood phylogeny showing the position of the Davidsoniella ecualypti isolate used for this genome. Represented are the four known species of Davidsoniella, with two Endoconidiophora species used as outgroup. Approximate likelihood ratio test values for branch support are shown as percentages.

The hybrid assembly of D. eucalypti presented here has a N-50 value (230092 bp) twice that of D. virescens (Wingfield et al. 2015b). This improvement in contig contiguity can be attributed to the inclusion of long-read PacBio sequences (English et al. 2012), a trend seen for many other genomes (Huddleston et al. 2014, Koren et al. 2013, Koren & Phillippy 2015). The availability of a highly contiguous genome sequence for one Davidsoniella species could provide the basis for genomic comparative studies. These should be of much interest as the higher gene number and larger genome size of D. eucalypti might point to an interesting evolutionary history for the genome of this species.

IMA Genome-F 10F

Draft genome sequence of Grosmannia galeiformis

Introduction

Grosmannia galeiformis was first described as Ceratocystis galeiformes from conifer infesting bark and ambrosia beetles in Scotland in 1951 (Bakshi 1951). It was later transfered to Ophiostoma (as Ophiostoma galeiforme; Mathiesen-Käärik 1953), and thereafter to Grosmannia (as G. galeiformis; Zipfel et al. 2006).

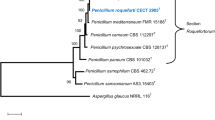

Grosmannia galeiformis is often found associated with conifer-infesting bark beetles and has been reported from Europe (Bakshi 1951, Linnakoski et al. 2012, Mathiesen-Käärik 1953, Zhou et al. 2004), South America (Zhou et al. 2004), and Africa (Zhou et al. 2004). Phylogenetic studies indicated that this species is part of a complex of several closely related species known as the G. galeiformis species complex, which is distinct from other species complexes in Leptographium s. lat. (Chang et al. 2019, De Beer et al. 2013 Linnakoski et al. 2012; Fig. 7). In this study, we sequenced and assembled the draft genome sequence for G. galeiformis, the key species representing the G. galeiformis species complex.

Phylogenetic tree generated from maximum likelihood analysis of a dataset consisted of partial beta-tubulin gene to authenticate the identity of G. galeiformis used in this study. Bootstrap values (>= 70; 1000 replicates) are indicated at nodes. Beta-tubulin gene sequence for G. galeiformis was extracted directly from genome assembly. Other authenticated reference sequences were obtained from GenBank database.

Sequenced Strain

United Kingdom: Elgin: on Pinus sylvestris (Scotch pine) infested with Tomicus piniperda, 29 Aug 1997, T. Kirisits & M.J. Wingfield (epitype isolate CMW 5290 = CBS 115711, PREM57491).

Nucleotide Sequence Accession Number

The genomic sequence of Grosmannia galeiformis (CMW 5290, CBS 115711) has been deposited at DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank under accession no. RQWE00000000. The version described in this paper is version RQWE01000000.

Methods

Genomic DNA was extracted from freeze-dried mycelium obtained from a single spore culture of G. galeiformis (CMW 5290). DNA extraction was done following a previously described method (Duong et al. 2013). Genome sequencing was carried out on the Illumina HiSeq 2000 platform (University of California Davis, CA). Two libraries (350 and 550 bp insert sizes) were prepared and sequenced to obtain 100 bp pair-end reads. Obtained pair-end reads were trimmed using Trimmomatic v. 0.36 (Bolger et al. 2014), and de novo assembled using SPAdes v. 3.9.0 (Bankevich et al. 2012). Scaffolds obtained from SPAdes was further placed into larger scaffolds using SSPACE-Standard v. 3.0 (Boetzer et al. 2011), and assembly gaps were filled using GapFiller v. 1.10 (Boetzer & Pirovano 2012). The completeness of the resulting assembly was estimated using Benchmarking Universal Single Copy Orthologs (BUSCO) program v. 2.0.1 with the Sordariomyceta odb9 dataset (Simão et al. 2015). Protein coding gene models were predicted using the MAKER genome annotation pipeline (Cantarel et al. 2008) with the combination of GeneMark v. 4.32 (using self-training; Lomsadze et al. 2005) and AUGUSTUS v3.2.2 (using species models optimised for Neurospora crassa; Stanke et al. 2006a) as gene predictors.

Results and Discussion

Over 25 million 100 bp pair-end reads were obtained after filtering and trimming. The final draft assembly consisted of 869 scaffolds that were over 500 bp in size. The assembly had a N50 of 67.79 Kb and and a genome size of around 26,44 Mb. BUSCO reported the score for the assembly of 97 %[D:5.8 %], F:1.8 %, M:0.6 %, n = 1348 (C: complete; D: duplicated; F: fragmented; M: missing, n = number of genes), which is comparable to that from other species of Leptographium s. lat. generated from previous studies (Wingfield et al. 2015a, 2016). Genome annotation using MAKER pipeline with GeneMark and AUGUSTUS as gene predictors resulted in 8527 protein-coding gene models. The genome of G. galeiformis generated in this study will add to the already growing genome resources for species of ophiostomatoid fungi (Wingfield et al. 2015a, b, 2016), which will facilitate future comparative genomic and evolutionary studies of these fungi (Fig. 7).

References

Al Adawi AO, Barnes I, Khan IA, Al Subhi AM, Al Jahwari AA, et al. (2013) Ceratocystis manginecans associated with a serious wilt disease of two native legume trees in Oman and Pakistan. Australasian Plant Pathology 42: 179–193.

Alfenas AC, Zauza EAV, Rosa OPP, Assi TF (2001) Sporothrix eucalypti, um novo patogeno do eucalipto no Brasil. Fitopatologia Brasileira 26: 221.

Alm T (2003) The witch trials of Finnmark, Northern Norway, during the 17th century: evidence for ergotism as a contributing factor. Economic Botany 57: 403–416.

Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ (1990) Basic local alignment search tool. Journal of Molecular Biology 215: 403–410.

Andjic V, Dell B, Barber P, Hardy G, Wingfield M, et al. (2011) Plants for planting; indirect evidence for the movement of a serious forest pathogen, Teratosphaeria destructans, in Asia. European Journal of Plant Pathology 131: 49–58.

Anisimova M, Gascuel O (2006) Approximate likelihood-ratio test for branches: a fast, accurate, and powerful alternative. Systematic Biology 55: 539–552.

Aylward J, Roets F, Dreyer LL, Wingfield MJ (2018) Teratosphaeria stem canker of Eucalyptus: two pathogens, one devastating disease. Molecular Plant Pathology: Epub ahead of print. DOI:10.1111/mpp.12758

Baker Engelbrecht CJ, Harrington TC (2005) Intersterility, morphology and taxonomy of Ceratocystis fimbriata on sweet potato, cacao and sycamore. Mycologia 97: 57–69.

Bakshi BK (1951) Studies on four species of Ceratocystis, with a discussion on fungi causing sapstain in Britain. Mycological Paper 35: 1–16.

Bankevich A, Nurk S, Antipov D, Gurevich AA, Dvorkin M, et al. (2011) SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. Journal of Computational Biology 19: 455–477.

Barber PA (2004) Forest pathology: the threat of disease to plantation forests in Indonesia. Plant Pathology Journal 3: 97–104.

Barber PA, Thu PQ, Hardy GE, Dell B (2012) Emerging disease problems in eucalypt plantations in Lao PDR. In: Proceedings of International Conference on the Impacts of Climate Change to Forest Pests and Diseases in the Tropics, 8–10 October (Mohammed C, Beadle C, Roux J, et al., eds): 79–84, Indonesia: Yogyakarta.

Boetzer M, Henkel CV, Jansen HJ, Butler D, Pirovano W (2011) Scaf-folding pre-assembled contigs using SSPACE. Bioinformatics 27: 578–579.

Boetzer M, Pirovano W (2012) Toward almost closed genomes with GapFiller. Genome Biology 13: R56.

Boetzer M, Pirovano W (2014) SSPACE-LongRead: scaffolding bacterial draft genomes using long read sequence information. BMC Bioinformatics 15: 211.

Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B (2014) Trimmomatic: Aflexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30: 2114–2120.

Bragança H, Diogo ELF, Neves L, Valente C, Araujo C, et al. (2015) Quambalaria eucalypti a pathogen of Eucalyptus globulus newly reported in Portugal and in Europe. Forest Pathology 46: 67–75.

Burgess TI, Andjic V, Hardy GE, Dell B, Xu D (2006) First report of Phaeophleospora destructans in China. Journal of Tropical Forest Science 18: 144–146.

Burgess TI, Wingfield MJ (2017) Pathogens on the move: a 100-year global experiment with planted eucalypts. BioScience 67: 14–25.

Cantarel BL, Korf I, Robb SMC, Parra G, Ross E, et al. (2008) MAKER: An easy-to-use annotation pipeline designed foremerging model organism genomes. Genome Research 18: 188–196.

Caporael LR (1976) Ergotism: the satan loosed in Salem? Science 192: 21

Castresana J (2000) Selection of conserved blocks from multiple alignments for their use in phylogenetic analysis. Molecular Biology and Evolution 17: 540–552.

Chang R, Duong TA, Taerum SJ, Wingfield MJ, Zhou X, De Beer ZW (2019) Ophiostomatoid fungi associated with the spruce bark beetle Ips typographus, including 11 new species from China. Persoonia 42: 50–74.

Chiara M, Fanelli F, Mulè G, Logrieco AF, Pesole G, et al. (2015) Genome sequencing of multiple isolates highlights sub-telomeric genomic diversity within Fusarium fujikuroi. Genome Biology and Evolution 7: 3062–3069.

Condon BJ, Leng Y, Wu D, Bushley KE, Ohm RA, et al. (2013) Comparative genome structure, secondary metabolite, and effector coding capacity across Cochliobolus pathogens. PLoS Genetics 9: e1003233.

Crosignani PG (2006) Current treatment issues in female hyperpro-lactinaemia. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology 125: 152–164.

Crous PW, Groenewald JZ, Summerell BA, Wingfield BD, Wingfield MJ (2009) Co-occurring species of Teratosphaeria on Eucalyptus. Persoonia 22: 38–48.

Dadant R (1950) On a new disease of Coffea robusta in New Caledonia. Revue Generale de Botanique 57: 1–11.

Darribo D, Taboada GL, Doallo R, Posada D (2012) jModelTest 2: More models, new heuristics and parallel computing. Nature Methods 9: 772.

De Beer ZW, Begerow D, Bauer R, Pegg GS, Crous PW, et al. (2006) Phylogeny of the Quambalariaceae fam. nov., including important Eucalyptus pathogens in South Africa and Australia. Studies in Mycology 55: 289–298.

De Beer ZW, Duong TA, Barnes I, Wingfield BD, Wingfield MJ (2014) Redefining Ceratocystis and allied genera. Studies in Mycology 79: 187–219.

De Beer ZW, Marincowitz S, Duong TA, Wingfield MJ (2017) Bretziella, a new genus to accommodate the oak wilt fungus, Ceratocystis fagacearum (Microascales, Ascomycota). MycoKeys 27: 1–19.

De Beer ZW, Wingfield MJ (2013) Emerging lineages in the Ophiostomatales. In: The Ophiostomatoid Fungi: expanding frontiers (Seifert KA, et al., eds): 21–46. [CBS Biodiversity Series no. 12.] Utrecht: CBS-KNAW Fungal Biodiversity Institute.

De Groot ANJA, Van Dongen PWJ, Vree TB, Hekster YA, Van Roosmalen J (1998) Ergot alkaloids: current status and review of clinical pharmacology and therapeutic use compared with other oxytocics in obstetrics and gynaecology. Drugs 56: 523–535.

De Vos L, Myburg AA, Wingfield MJ, Desjardins AE, Gordon TR, et al. (2007) Complete genetic linkage maps from an interspecific cross between Fusarium circinatum and Fusarium subglutinans. Fungal Genetics and Biology 44: 701–714.

De Vos L, Steenkamp ET, Martin SH, Santana QC, Fourie G, et al. (2014) Genome-wide macrosynteny among Fusarium species within the Gibberella fujikuroi complex revealed by amplified fragment length polymorphisms. PLoS One 9: e114682.

De Vos L, Van der Nest MA, Van der Merwe NA, et al. (2011) Genetic analysis of growth, morphology and pathogenicity in the F1 progeny of an interspecific cross between Fusarium circinatum and Fusarium subglutinans. Fungal Biology 115: 902–908.

Deng CH, Plummer KM, Jones DAB, Mesarich CH, Shiller J, et al. (2017) Comparative analysis of the predicted secretomes of Rosaceae scab pathogens Venturia inaequalis and V. pirina reveals expanded effector families and putative determinants of host range. BMC Genomics 18: 339.

Dereeper A, Audic S, Claverie JM, Blanc G (2010) BLAST-EXPLORER helps you building datasets for phylogenetic analysis. BMC Evolutionary Biology 10: 8.

Dereeper A, Guignon V, Blanc G, Audic S, Buffet S, et al. (2008) Phylogeny.fr: robust phylogenetic analysis for the non-specialist. Nucleic Acids Research 36: W465–W469.

Douhan GW, Smith ME, Huyrn KL, Westbrook A, Beerli P, et al. (2008) Multigene analysis suggests ecological speciation in the fungal pathogen Claviceps purpurea. Molecular Ecology 17: 2276–2286.

Doyle JJ, Doyle JL (1987) A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf tissue. Phytochemistry Bulletin 190:11-15

Duong TA, de Beer ZW, Wingfield BD, Wingfield MJ (2013) Characterization of the mating-type genes in Leptographium procerum and Leptographium profanum. Fungal Biology 117: 411–421.

Edgar RC (2004) MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Research 32: 1792–1797.

English AC, Richards S, Han Y, Wang M, Vee V, et al. (2012) Mind the gap: upgrading genomes with Pacific Biosciences RS long-read sequencing technology. PLoS ONE 7: e47768.

Frantzeskakis L, Kracher B, Kusch S, Yoshikawa-Maekawa M, Bauer S, et al. (2018) Signatures of host specialization and a recent transposable element burst in the dynamic one-speed genome of the fungal barley powdery mildew pathogen. BMC Genomics 19: 381.

Fuller JG (1968) The Day of St. Anthony’s Fire: the suspenseful, true account of a medieval plague in modern times, and of the scientific detective work that traced it to a surprising cause. New York: Macmillan.

Garc’a-Alcalde F, Okonechnikov K, Carbonell J, Cruz LM, Gštz S, et al. (2012) Qualimap: evaluating next-generation sequencing alignment data. Bioinformatics 28:2678–2679

Gardiner DM (2018) Genome sequences of three isolates of Fusarium verticillioides. Microbiology Resource Announcements 7: e00918-18.

Geiser DM, Aoki T, Bacon CW, Baker SE, Bhattacharyya MK, et al. (2012) One fungus, one name: Defining the genus Fusarium in a scientifically robust way that preserves longstanding use. Phytopathology 103: 400–408.

Gnocato FS, Dracatos PM, Karaoglu H, Zhang P, Berlin A, et al. (2017) Development, characterization and application of genomic SSR markers for the oat stem rust pathogen Puccinia graminis f. sp. avenae. Plant Pathology 67: 457–466.

Gordon TR, Storer AJ & Okamoto D (1996) Population structure of the pitch canker pathogen, Fusarium subglutinans f. sp. pini, in California. Mycological Research 100: 850–854.

Gordon TR, Swett CL & Wingfield MJ (2015) Management of Fusarium diseases affecting conifers. Crop Protection 73: 28–39.

Greyling I, Wingfield MJ, Coetzee MPA, Marincowitz S, Roux J (2016) The Eucalyptus shoot and leaf pathogen Teratosphaeria destructans recorded in South Africa. Southern Forests 78: 123–129.

Guindon S, Dufayard J-F, Lefort V, Anisimova M, Hordijk W, et al. (2010) New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: Assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Systematic Biology 59: 307–321.

Guindon S, Gascuel O (2003) A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Systematic Biology 52: 696–704.

Gurevich A, Saveliev V, Vyahhi N, Tesler G (2013) QUAST: Quality assessment tool for genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 29: 1072–1075.

Hall B, DeRego T, Geib S (2014) GAG: the genome annotation generator (version 1.0): https://doi.org/genomeannotation.github.io/GAG.

Harrington TC, Steimel J, Kile G (1998) Genetic variation in three Ceratocystis species with outcrossing, selfing and asexual reproductive strategies. European Journal of Forest Pathology 28: 217–226.

Huddleston J, Ranade S, Malig M, Antonacci F, Chaisson M, et al. (2013) Reconstructing complex regions of genomes using long-read sequencing technology. Genome Research 24: 688–696.

Hunter GC, Crous PW, Carnegie AJ, Burgess TI, Wingfield MJ (2011) Mycosphaerella and Teratosphaeria diseases of Eucalyptus; easily confused and with serious consequences. Fungal Diversity 50: 145–166.

James TY, Sun S, Li W, Heitmen J, Kuo HC, et al. (2013) Polyporales genomes reveal the genetic architecture underlying tetrapolar and bipolarmating systems. Mycologia 105: 1374–1390.

Jeong H, Lee S, Choi GJ, Lee S, Yun S-H, et al. (2013) Draft genome sequence of Fusarium fujikuroi B14, the causal agent of the bakanae disease of rice. Genome Announcements 1: e00035-13.

Katoh K, Standley DM (2013) MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: Improvements in performance and usability. Molecular Biology and Evolution 30: 772–780.

Kearse M, Moir R, Wilson A, Stones-Havas S, Cheung M, et al. (2012) Geneious Basic: An integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics 28: 1647–1649.

Keller O, Kollmar M, Stanke M, Waack S (2011) A novel hybrid gene prediction method employing protein multiple sequence alignments. Bioinformatics 27: 757–763.

Kijpornyongpan T, Aime MC (2017) Taxonomic revisions in the Microstromatales: two new yeast species, two new genera, and validation of Jaminaea and two Sympodiomycopsis species. Mycological Progress 16: 495–505.

Kijpornyongpan T, Mondo SJ, Barry K, Sandor, L, Lee L, et al. (2018) Broad genomic sampling reveals a smut pathogenic ancestry of the fungal clade Ustilaginomycotina. Molecular Biology and Evolution 35: 1840–1854.

Kile G (1993). Plant diseases caused by species of Ceratocystis sensu stricto and Chalara. In: Ceratocystis and Ophiostoma: taxonomy, ecology and pathogenicity (Wingfield MJ, Seifert KA, Webber JF, eds): 173–184. S. Paul, MN: American Phytopatho-logical Society Press.

Kile GA, Harrington TC, Yuan ZQ, Dudzinski MJ, Old KM (1996) Ceratocystis eucalypti sp. nov., a vascular stain fungus from eucalypts in Australia. Mycological Research 100: 571–579.

Klosterman SJ, Subbarao KV, Kang S, Veronese P, Gold SE, et al. (2011) Comparative genomics yields insights into niche adaptation of plant vascular wilt pathogens. PLoS Pathogens 7: e1002137.

Kolar’ik M, Sl’avikov’a E, Pažoutov’a S (2006) The taxonomic and ecological characterisation of the clinically important heterobasio-diomycete Fugomyces cyanescens and its association with bark beetles. Czech Mycology 58: 81–98.

Konishi M, Hatada Y, Horiuchi J (2013) Draft genome sequence of the basidiomycetous yeast-like fungus Pseudozyma hubeiensis SY62, which produces an abundant amount of the biosurfactant mannosylerythritol lipids. Genome Announcements 1: e00409-13-e00409-13.

Koren S, Harhay GP, Smith TP, Bono JL, Harhay DM, et al. (2013) Reducing assembly complexity of microbial genomes with single-moleculesequencing. Genome Biology 14: R101.

Koren S, Phillippy AM (2015) One chromosome, one contig: complete microbial genomes from long-read sequencing and assembly. Current Opinion in Microbiology 23: 110–120.

Koren S, Walenz BP, Berlin K, Miller JR, Bergman NH, et al. (2017) Canu: scalable and accurate long-read assembly via adaptive k-mer weighting and repeat separation. Genome Research 27: 722–736.

Korf I (2004) Gene finding in novel genomes. BMC Bioinformatics 5: 59.

Kuan CS, Yew SM, Toh YF, Chan CL, Lim SK, et al. (2015) Identification and characterization of a rare fungus, Quambalaria cyanescens, isolated from the peritoneal fluid of a patient after nocturnal intermittent peritoneal dialysis. PLoS ONE 10: 1–15.

Kurtz S, Phillippy A, DelcherAL, Smoot M, Shumway M, et al. (2004) Versatile and open software for comparing large genomes. Genome Biology 5: R12.

Langmead B, Salzberg SL (2012) Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nature Methods 9: 357–359.

Leslie JF, Summerell BA (2006) The Fusarium Laboratory Manual. Iowa: Wiley-Blackwell.

Li H, Durbin R (2009) Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheelertransform. Bioinformatics 25: 1754–1760.

Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, et al. (2009) The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25: 2078–2079.

Linnakoski R, De Beer ZW, Duong TA, Niemelä P, Pappinen A, Wingfield MJ (2012) Grosmannia and Leptographium spp. associated with conifer-infesting bark beetles in Finland and Russia, including L. taigense sp. nov. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 102: 375–399.

Lomsadze A, Burns PD, Borodovsky M (2014) Integration of mapped RNA-Seq reads into automatic training of eukaryotic gene finding algorithm. Nucleic Acids Research 42: e119.

Lomsadze A, Ter-Hovhannisyan V, Chernoff Y, Borodovsky M (2005) Gene identification in novel eukaryotic genomes by self-training algorithm. Nucleic Acids Research 33: 6494–6506.

Lyons PC, Plattner RD, Bacon CW (1986) Occurrence of peptide and clavine ergot alkaloids in tall fescue grass. Science 232: 487–489.

Ma L-J, Van der Does HC, Borkovich KA, Coleman JJ, Daboussi MJ, et al. (2010) Comparative genomics reveals mobile pathogenicity chromosomes in Fusarium. Nature 464: 367–373.

Mathiesen-Käärik A (1953) Eine Übersicht über die gewöhnlichsten mit Borkenkäfern assoziierten Bläuepilze in Schweden und einige für Schweden neue Bläuepilze. Meddelanden från Statens Skogsforskiningsinstitut 43: 1–74.

Mayers CG, McNew DL, Harrington TC, Roeper RA, Fraedrich SW, et al. (2015) Three genera in the Ceratocystidaceae are the respective symbionts of three independent lineages of ambrosia beetles with large, complex mycangia. Fungal Biology 119: 1075–1092.

Mbenoun M, De Beer ZW, Wingfield BD, Roux J (2014) Reconsidering species boundaries in the Ceratocystis paradoxa complex, including a new species from oil palm and cacao in Cameroon. Mycologia 106: 757–784.

Menzies JG, Turkington TK (2015) An overview of the ergot (Claviceps purpurea) issue in western Canada: Challenges and solutions. Canadian Journal of Plant Pathology 37: 40–51.

Micale V, Incognito T, Ignoto A, Rampello L, Spart M, et al. (2006) Dopaminergic drugs may counteract behavioral and biochemical changes induced by models of brain injury. European Neuropsy-chopharmacology 16: 195–203.

Mikheenko A, Prjibelski A, Saveliev V, Antipov D, Gurevich A (2018) Versatile genome assembly evaluation with QUAST-LG. Bioinformatics 34: i142–i150.

Miles C, Lane G, E. di Menna M, Garthwaite I, L. Piper E, et al. (1996) High levels of ergonovine and lysergic acid amide in toxic Achnatherum inebrians accompany infection by an Acremonium-like endophytic fungus. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 44: 1285–1290.

Möller EM, Bahnweg G, Sandermann H, Geiger HH, (1992) Asimple and efficient protocol for isolation of high molecular weight DNA from filamentous fungi, fruit bodies, and infected plant tissues. Nucleic Acids Research 20: 6115–6116.

Möller M, Stukenbrock EH (2017) Evolution and genome architecture in fungal plant pathogens. Nature Reviews Microbiology 15: 756–771.

Nel WJ, Duong TA, Wingfield BD, Wingfield MJ, De Beer ZW (2018) A new genus and species for the globally important, multihost root pathogen Thielaviopsis basicola. Plant Pathology 67: 871–882.

Niehaus E-M, Kim H-K, Münsterkotter M, Janevsks S, Arndt B, et al. (2017a) Comparative genomics of geographically distant Fusarium fujikuroi isolates revealed two distinct pathotypes correlating with secondary metabolite profiles. PLoS Pathogens 13: e1006670.

Niehaus E-M, Münsterkotter M, Proctor RH, Brown DW, Sharon A, et al. (2017b) Comparative “omics” of the Fusarium fujikuroi species complex highlights differences in genetic potential and metabolite synthesis. Genome Biology and Evolution 8: 3574–3599.

Nikolenko SI, Korobeynikov Al, Alekseyev MA (2013) BayesHammer: Bayesian clustering for error correction in single-cell sequencing. BMC Genomics 14 (suppl. 1):S7.

Nurk S, Bankevich A, Antipov D, Gurevich A, Korobeynikov A, et al. (2013) Assembling genomes and mini-metagenomes from highly chimeric reads. Research in Computational Molecular Biology 7821: 158–170.

O’Donnell K, Cigelnik E & Nirenberg HI (1998) Molecular systematics and phylogeography of the Gibberella fujikuroi species complex. Mycologia 90: 465–493.

O’Donnell K, Nirenberg HI, Aoki T, Cigelnik E (2000) A multigene phylogeny of the Gibberella fujikuroi species complex: detection of additional phylogenetically distinct species. Mycoscience 41: 61–78.

Old KM, Pongpanich K, Thu PQ, Wingfield MJ, Yuan ZQ (2003) Phaeophleospora destructans causing leafblight epidemics in South East Asia. Feb. Vol. 2 — Offered papers ICPP: 165, Christchurch, NewZealand

Paap T, Burgess TI, McComb JA, Shearer, BL, Hardy GE (2008) Quambalaria species, including Q. coyrecup sp. nov., implicated in canker and shoot blight diseases causing decline of Corymbia species in the southwest of Western Australia. Mycological Research 112: 57–69.

Park RF, Keane PJ, Wingfield MJ, Crous PW (2000) Fungal diseases of eucalypt foliage. In: Diseases and Pathogens of Eucalypts (Keane PJ, Kile GA, Podger FD, et al., eds): 153–239. Collingwood: CSIRO Publishing.

Pažoutov’a S, Pešicov K, Chud’čkov M, Šråtka P, Kolaž’k M (2015) Delimitation of cryptic species inside Claviceps purpurea. Fungal Biology 119: 7–26.

Pažoutov’a S, Olsovska J, Linka M, Kolinska R, Flieger M (2000) Chemoraces and habitat specialization of Claviceps purpurea populations. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 66: 5419–5425.

Pegg GS, O’Dwyer C, Carnegie AJ, Burgess TI, Wingfield MJ, et al. (2008) Quambalaria species associated with plantation and native eucalypts in Australia. Plant Pathology 57: 702–714.

Pegg GS, Shuey LS, Carnegie AJ, Wingfield MJ, Drenth A (2011) Variability in aggressiveness of Quambalaria pitereka isolates. Plant Pathology 60: 1107–1117.

Pegg GS, Webb RI, Carnegie AJ, Wingfield MJ, Drenth A (2009) Infection and disease development of Quambalaria spp. on Corymbia and Eucalyptus species. Plant Pathology 58: 642–654.

Perez CA, De Beer ZW, Altier NA, Wingfield MJ, Blanchette RA (2008) Discovery of the eucalypt pathogen Quambalaria eucalypti infecting a non-Eucalyptus host in Uruguay. Australasian Plant Pathology 37: 600–604.

Quaedvlieg W, Binder M, Groenewald JZ, Summerell BA, Carnegie AJ, et al. (2014) Introducing the Consolidated Species Concept to resolve species in the Teratosphaeriaceae. Persoonia 33: 1–40.

Que Y, Xu L, Wu Q, Liu, Y, Ling H, et al. (2014) Genome sequencing of Sporisorium scitamineum provides insights into the pathogenic mechanisms of sugarcane smut. BMC Genomics 15: 996.

Raffaele S, Kamoun S (2012) Genome evolution in filamentous plant pathogens: why bigger can be better. Nature Reviews Microbiology 10: 417–430.

Rafiei V, Banihashemi Z, Bautista-Jalon LS, Del Mar Jimenez-Gasco M, Turgeon BG, et al. (2018) Population genetics of Verticillium dahliae in Iran based on microsatellite and single nucleotide polymorphism markers. Phytopathology 108: 780–788.

Ronquist F, Teslenko M, van der Mark P, Ayres DL, Darling A, et al. (2014) MrBayes 3.2: Efficient bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Systematic Biology 61: 539–542.

Roux J, van Wyk M, Hatting H, Wingfield MJ (2004) Ceratocystis species infecting stem wounds on Eucalyptus grandis in South Africa. Plant Pathology 53: 414–421.

Saika A, Koike H, Hori T, Fukuoak T (2014) Draft genome sequence of the yeast Pseudozyma antarctica type strain JCM10317, a producer of the glycolipid biosurfactants, mannosylerythritol lipids. Genome Announcements 2: 4–5.

Scauflaire J, Gourgue M, & Munaut F (2011) Fusarium temperatum sp. nov. from maize, an emergent species closely related to Fusarium subglutinans. Mycologia 103: 586–597.

Schardl CL, Young CA, Hesse U, Amyotte SG, Andreeva K, et al. (2015) Plant-symbiotic fungi as chemical engineers: multi-genome analysis of the clavicipitaceae reveals dynamics of alkaloid loci. PLoS Genetics 9: e1003323.

Scott P (2009) Ergot alkaloids: extent of human and animal exposure. World Mycotoxin Journal 2:141-149.

Simão FA, Waterhouse RM, Ioannidis P, Kriventseva EV, Zdobnov EM (2015) BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics 31: 3210–3212.

Srivastava, AK, Kashyap, PL, Chakdar, H, Kumar M, Srivastava AK, et al. (2018) First de novo draft genome sequence of the pathogenic fungus Fusarium udum F02845, associated with pigeonpea (Cajanus cajan L. Millspaugh) wilt. Microbiology Resource Announcements 7: e01001-18.

Stanke M, Morgenstern B (2005) AUGUSTUS: a web server for gene prediction in eukaryotes that allows user-defined constraints. Nucleic Acids Research 33: W465–W467.

Stanke M, Diekhans M, Baertsch R, Haussler D (2008) Using native and syntenically mapped cDNA alignments to improve de novo gene finding. Bioinformatics 24: 637–644.

Stanke M, Keller O, Gunduz I, Hayes A, Waack S, Morgenstern B (2006a) AUGUSTUS: ab initio prediction of alternative transcripts. Nucleic Acids Research 34: W435–W439.

Stanke M, Tzvetkova A, Morgenstern B (2006b) AUGUSTUS at EGASP: using EST, protein and genomic alignments for improved gene prediction in the human genome. Genome Biology 7 (suppl. 1): S11.11–S11.18.

Steenkamp ET, Makhari OM, Coutinho TA, Wingfield BD, Wingfield MJ (2014) Evidence for a new introduction of the pitch canker fungus Fusarium circinatum in South Africa. Plant Pathology 63: 530–538.

Swofford DL (2002) PAUP*. Phylogenetic analysis using parsimony (*and other methods). Version 4.0 b10 (computer program). Sunderland MA: Sinauer Associates

Tarigan M, Roux J, van Wyk M, Tjahjono B, Wingfield MJ (2011) A new wilt and die-back disease of Acacia mangium associated with Ceratocystis manginecans and C. acaciivora sp. nov. in Indonesia. South African Journal of Botany 77: 292–304.

Tavare S (1986) Some probabilistic and statistical problems in the analysis of DNA sequences. In: Lectures on Mathematics in the Life Sciences 17: 57–86, American Mathematical Society, Rhode Island.

Ter-Hovhannisyan V, Lomsadze A, Chernoff YO, Borodovsky M (2008) Gene prediction in novel fungal genomes using an ab initio algorithm with unsupervised training. Genome Research 18: 1979–1990.

Toome M, Kuo A, Henrissat B, Lipzen A, Tritt A, et al. (2014) Draft genome sequence of a rare smut relative, Tilletiaria anomala UBC 951. Genome Announcements 2: 2–3.

Van der Linde EJ, Pešicov K, Pažoutov’a S, Stodålkov E, Flieger M, et al. (2016) Ergot species of the Claviceps purpurea group from South Africa. Fungal Biology 120: 917–930.

Van der Nest MA, Beirn LA, Crouch JA, Demers JE, De Beer ZW, et al. (2014) Draft genomes of Amanita jacksonii, Ceratocystis albifundus, Fusarium circinatum, Huntiella omanensis, Leptographium procerum, Rutstroemia sydowiana, and Sclerotinia echinophila. IMA Fungus 5: 473–486.

Van Wyk M, Wingfield BD, Wingfield MJ (2013) Ceratocystis species in the Ceratocystis fimbriata complex. In: The Ophiostomatoid Fungi: expanding frontiers (Seifert KA, De Beer ZW, Wingfield MJ, eds): 65–73. [CBS Biodiversity Series no. 12.] Utrecht: CBSKNAW Fungal Biodiversity Institute.

Van Wyk S, Wingfield BD, De Vos L, Santana QC, Van der Merwe NA, et al. (2018) Multiple independent origins for a subtelomeric locus associated with growth rate in Fusarium circinatum. IMA Fungus 9: 27–36.

Walker BJ, Abeel T, Shea T, Priest M, Abouelliel A, et al. (2014) Pilon: an integrated tool for comprehensive microbial variant detection and genome assembly improvement. PLoS ONE 9: e112963.

Wang N, Ai P, Tang Y, Zhang J, Dai X, et al. (2015a) Draft genome sequence of the rice kernel smut Tilletia horrida Strain QB-1. Genome Announcements 3: e00621-15.

Wang QM, Begerow D, Groenewald M, Liu XZ, Theelen B, et al. (2015b) Multigene phylogeny and taxonomic revision of yeasts and related fungi in the Ustilaginomycotina. Studies in Mycology 81: 55–83.

Waterhouse RM, Seppey M, Simao FA, Manni M, Ioannidis P, et al. (2017) BUSCO applications from quality assessments to gene prediction and phylogenomics. Molecular Biology and Evolution 35: 543–548.

Wiemann P, Sieber CMK, Von Bargen K, Studt L, Niehaus EM, et al. (2013) Unleashing the cryptic genome: genome-wide analyses of the rice pathogen Fusarium fujikuroi reveal complex regulation of secondary metabolism and novel metabolites. PLos Pathogens 9: e1003475.

Wingfield BD, Ades PK, Al-Naemi FA, Beir LA, Bihon W, et al. (2015a) IMA Genome-F 4. Draft genome sequences of Chrysoporthe austroafricana, Diplodia scrobiculata, Fusarium nygamai, Leptographium lundbergii, Limonomyces culmigenus, Stagonosporopsis tanaceti, and Thielaviopsis punctulata. IMA Fungus 6: 233–248.

Wingfield BD, Barnes I, De Beer ZW, de Vos L, Duong TA, et al. (2015b) IMA Genome-F 5. Draft genome sequences of Ceratocystis eucalypticola, Chrysoporthe cubensis, C. deuterocubensis, Davidsoniella virescens, Fusarium temperatum, Graphilbum fragrans, Penicillium nordicum, and Thielaviopsis musarum. IMA Fungus 6: 493–506.

Wingfield BD, Berger DK, Steenkamp ET, Lim HJ, Duong TA, et al. (2017) IMA Genome-F 6: draft genome of Cercospora zeina, Fusarium pininemorale, Hawksworthiomyces lignivorus, Huntiella decipiens and Ophiostoma ips. IMA Fungus 8: 385–396.

Wingfield BD, Bills GF, Dong Y, Huang W, Nei WJ, et al. (2018) IMA Genome-F 9. Draft genome sequence of Annulohypoxylon stygium, Aspergillus mulundensis, Berkeleyomyces basicola (syn. Thielaviopsis basicola), Ceratocystis smalleyi, two Cercospora beticola strains, Coleophoma cylindrospora, Fusarium fracticaudum, Phialophora cf. hyalina, and Morchella septimelata. IMA Fungus 9: 199–223.

Wingfield BD, Duong TA, Hammerbacher A, Van der Nest MA, Wilson A, et al. (2016) IMA Genome-F 7. Draft genome sequences for Ceratocystis fagacearum, C. harringtonii, Grosmannia penicillata, and Huntiella bhutanensis. IMA Fungus 7: 317–323.

Wingfield BD, Steenkamp ET, Santana QC, Coetzee MPA, Bam S, et al. (2012) First fungal genome sequence from Africa: a preliminaryanalysis. South African Journal of Science 108: 1–2.

Wingfield BD, Van Wyk M, Roos H, Wingfield MJ (2013) Ceratocystis: emerging evidence for discrete generic boundaries. In: The Ophiostomatoid Fungi: expanding frontiers (Seifert KA, De Beer ZW, Wingfield MJ, eds): 57–64. [CBS Biodiversity Series no. 12.] Utrecht: CBS-KNAW Fungal Biodiversity Institute.

Wingfield MJ, Crous PW, Boden D (1996) Kiiramyces destructans sp. nov., a serious leaf pathogen of Eucalyptus in Indonesia. South African Journal of Botany 62: 325–327.

Wingfield MJ, Crous PW, Swart WJ (1993) Sporothrix eucalypti (sp. nov.), a shoot and leaf pathogen of Eucalyptus in South Africa. Mycopathologia 123: 159–164.

Xu J, Saunders CW, Hu P, Grant, RA, Noekhout T, et al. (2007) Dandruff-associated Malassezia genomes reveal convergent and divergent virulence traits shared with plant and human fungal pathogens. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 104: 18730–18735.

Xu J-R, Yan K, Dickman MB, Leslie JF, (1995) Electrophoretic karyotypes distinguish the biological species of Gibberella fujikuroi (Fusarium section Liseola). Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions 8: 74–84.

Zhao Z, Liu H, Wang C, Xu JR (2013) Comparative analysis of fungal genomes reveals different plant cell wall degrading capacity in fungi. BMC Genomics 14: 274.

Zhou XD, De Beer ZW, Harrington TC, McNew D, Kirisits T, Wingfield MJ (2004) Epitypification of Ophiostoma galeiformis and phylogeny of species in the O. galeiformis complex. Mycologia 96: 1306–1315.