Abstract

Background

Most current clinical guidelines on primary coronary heart disease prevention emphasize the importance of risk stratification. Tools for cardiovascular risk estimation have been produced in many countries, although their use has been limited. The availability of new tools that include additional risk factors might lead to their more widespread use. The objective of our study was to produce an updated version of an existing chart for the estimation of cardiovascular disease risk using Italian population data and including high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (HDL-C) levels as a predictor.

Methods

Data were analyzed from nine population studies run in Italy, which included a total of 8054 men and 3206 women aged 45–74 years. The individuals included in these studies had no history of cardiovascular events or diabetes mellitus.

During a mean follow-up of 10 years (range 5–15), incidence data were collected for non-fatal and fatal cases of major cardiovascular diseases (coronary heart disease, cerebrovascular diseases, and peripheral artery diseases). Findings for major cardiovascular risk factors (i.e. sex, age, systolic blood pressure, serum total cholesterol levels, HDL-C levels, smoking habits) at study entry and their relationship with the occurrence of events during the follow-up were used to develop models for the prediction of cardiovascular events. These were multivariate models, based on a log-linear model incorporating the Weibull distribution, and separate models were developed for men and women.

Results

In 10 years, 461 new cardiovascular events occurred among men and 147 among women. The models showed good predictive power, with around 30% of events located in the upper decile of the estimated risk, and around 50% in the upper quintile of estimated risk. The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve, calculated based on internal validation only, was 72%, indicating favorable diagnostic performance of the models.

The independent predictive power of HDL-C was strong, with 1% increase in HDL-C level being associated with a decrease in the incidence of cardiovascular diseases of almost 1% among men and almost 2% among women.

A chart accommodating sex, age, total cholesterol level, HDL-C level, systolic blood pressure, and cigarette consumption was subsequently produced. The inclusion of HDL-C levels in this chart was novel for a risk chart in Italy, as it had not been included in previous editions of the same tool. A special feature of this chart was a new section dealing with the estimate of the ‘relative risk,’ defined by the ratio of absolute risk to the risk expected on the basis of the age, sex, and average age-specific risk factor levels of the involved populations.

Conclusions

The cardiovascular risk assessment devised in the current study represents an improved means for physicians to determine cardiovascular risk and discuss the risk with patients. The chart could be used in countries where the background risk is similar to that of the Italian population; however, external validation of the model is required to adequately assess transferability, and until then the chart should be used with caution in non-Italian populations. Compared with earlier tools, it has the advantage of including HDL-C levels as a predictor of cardiovascular risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

American Heart Association. Coronary risk handbook: estimating the risk of coronary heart disease in daily practice. Dallas (TX): AHA, 1973

Anderson KM, Odell PM, Wilson PWF, et al. Cardiovascular disease risk profiles. Am Heart J 1991; 121: 293–8

Prevention of coronary heart disease in clinical practice: recommendations of the Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology, European Atherosclerosis Society and European Society of Hypertension. Eur Heart J 1994; 15: 1300-31

Haq IU, Jackson PR, Yeo WW, et al. Sheffield risk and treatment table for cholesterol lowering for primary prevention of coronary heart disease. Lancet 1995; 346(8988): 1467–71

McCormack JP, Levine M, Rangno RE. Primary prevention of heart disease and stroke: a simplified approach to estimating risk of events and making drug treatment decisions. CMAJ 1997; 157: 422–8

Prevention of coronary heart disease in clinical practice: recommendations of the Second Joint Task Force of European and other Societies on coronary prevention. Eur Heart J 1998; 19: 1434-503

National Heart & Lung Institute. Joint British recommendations on prevention of coronary heart disease in clinical practice. British Cardiac Society, British Hyperlipidaemia Association, British Hypertension Society, endorsed by the British Diabetic Association. Heart 1998; 80(2): 1–29

Cardiac risk assessment V.98.02 [computer program]. PC version. Manchester: University of Manchester, 1998

Wilson PWF, D’Agostino RB, Levy D, et al. Prediction of coronary heart disease using risk factor categories. Circulation 1998; 97: 1837–47

Wallis EJ, Ramsay LE, Ul Haq I, et al. Coronary and cardiovascular risk estimation for primary prevention: validation of a new Sheffield table in the 1995 Scottish health survey population. BMJ 2000; 320(7236): 671–6

Thomsen T. Prediction and prevention of cardiovascular diseases: Precard© [thesis]. Copenhagen: University of Copenhagen, 2000

Stevens RJ, Kothari V, Adler AI, et al. The UKPDS risk engine: a model for the risk of coronary heart disease in type II diabetes (UKPDS 56). Clin Sci 2001; 101(6): 671–9

American Heart Association. Health risk awareness [online]. Available from URL: http://www.americanheart.org [Accessed 2007 Sep 1]

Procam risk calculator [online]. Available from URL: http://www.CHD-Taskforce.com [Accessed 2007 Sep 1]

Assmann G, Cullen P, Schulte H. Simple scoring scheme for calculating the risk of acute coronary events based on the 10-year follow-up of the prospective cardiovascular Munster (PROCAM) study. Circulation 2002; 105(3): 310–5

Conroy RM, Pyorala K, Fitzgerald AP, et al. Estimation of ten-year risk of fatal cardiovascular disease in Europe: the SCORE project. Eur Heart J 2003; 24(11): 987–1003

Jackson R. Updated New Zealand cardiovascular disease risk-benefit prediction guide. BMJ 2000; 320: 709–10

National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). Third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation 2002; 106: 3143–421

Fourth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and other societies on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (constituted by representatives of nine societies and by invited experts). European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2007 Sep; 14 Suppl. 2: S1-113

Keys A, Menotti A, Aravanis C, et al. The Seven Countries Study: 2289 deaths in 15 years. Prev Med 1984; 13: 141–54

Menotti A, Lanti M, Puddu PE, et al. Northern vs Southern European population bases in prediction of coronary incidence: a re-analysis and reappraisal of the Seven Countries Study in view of a European coronary risk chart. Heart 2000; 84: 238–44

Menotti A, Lanti M, Puddu PE. Comparison of the Framingham risk function-based coronary chart with risk function from an Italian population study. Eur Heart J 2000; 21: 365–70

Haq IU, Ramsay LE, Yeo WW, et al. Is the Framingham risk function valid for northern European populations? A comparison of methods for estimating absolute coronary risk in high risk men. Heart 1999; 81: 40–6

Thomsen TF, McGee D, Davidson M, et al. A cross-validation of risk-scores for coronary heart disease mortality based on data from the Glostrup Population Studies and Framingham Heart Study. Int J Epidemiol 2002; 31: 817–22

de Visser CL, Bilo HJ, Thomsen TF, et al. Prediction of coronary heart disease: a comparison between the Copenhagen risk score and the Framingham risk score applied to a Dutch population. J Intern Med 2003; 253: 553–62

Sans S, Fitzgerald AP, Royo D, et al. Calibrating the SCORE cardiovascular risk chart for use in Spain [in Spanish]. Rev Esp Cardiol 2007; 60: 476–85

Panagiotakos DB, Fitzgerald AP, Pitsavos C, et al. Statistical modelling of 10-year fatal cardiovascular disease risk in Greece: the HellenicSCORE (a calibration of the ESC SCORE project). Hellenic J Cardiol 2007; 48: 55–63

Manuale del Rischio Coronarico. Per stimare il rischio coronarico nella pratica medica. Udine: Associazione Nazionale Centri per le Malattie Cardiovascolari e CIBA-GEIGY, 1980

Menotti A, Lanti M, Agabiti-Rosei E, et al. Riskard 2005: new tools for prediction of cardiovascular disease risk derived from Italian population studies. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2005; 15: 426–40

Menotti A, Lanti M, Puddu PE, et al. An Italian chart for cardiovascular risk prediction: its scientific basis. Ann Ital Med Int 2001; 16: 240–51

Gordon DJ, Probstfield JL, Garrison RJ, et al. High density lipoprotein cholesterol and cardiovascular disease: four prospective American studies. Circulation 1989; 79: 8–15

Wilson PW, Anderson KM, Castelli WP. Twelve-year incidence of coronary heart disease in middle-aged adults during the era of hypertensive therapy. Am J Med 1991; 90: 11–6

Assman G, Cullen P, Schulte H. The Munster Heart Study (PROCAM): results of follow-up at 8 years. Eur Heart J 1998; 19 Suppl. A: A2–A11

Sharrett AR, Ballantyne CM, Coady SA, et al. Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study Group. Coronary heart disease prediction from lipoprotein cholesterol esters, triglycerides, lipoprotein (a), apolipoproteins A-1 and B, HDL density subfractions: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Circulation 2001; 104: 1108–13

Carter PH, Gotto A, LaRosa JC, for the Treating to New Targets Investigators, et al. HDL cholesterol, very low levels of LDL cholesterol, and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med 2007; 357: 301–10

Menotti A, Lanti M, Puddu PE. Epidemiologia delle malattie cardiovascolari. Insegnamenti dalle Aree Italiane del Seven Countries Study. Rome: Cardioricerca Ed., 1999: 1–532

Menotti A, Lanti M, Puddu PE, et al. First risk functions for prediction of coronary and cardiovascular disease incidence in the Gubbio Population Study. Ital Heart J 2000; 1: 394–9

Fazzini PF, Prati PL, Rovelli F, et al. Epidemiology of silent myocardial ischemia in asymptomatic middle-aged men: the ECCIS Project. Am J Cardiol 1993; 72: 1383–8

Descovich GC, Aluigi L, Benassi MS, et al. The Brisighella Investigation: results of the observational Study 1972–1980. Minerva Cardioangiol 1985; 33: 565–74

The RIFLE Research Group. Presentation of the RIFLE project: risk factors and life expectancy. Eur J Epidemiol 1993; 9: 459–76

Averna MR, Barbagallo CM, Montalto G, et al. Progetto di epidemiologia e prevenzione Ventimiglia di Sicilia: dati di popolazione. G Arterioscl 1992; 17: 83–7

Muiesan ML, Pasini GF, Salvetti M, et al. Cardiac and vascular structural changes: prevalence and relation to ambulatory blood pressure in a middle-aged general population in Northern Italy: The Vobarno Study. Hypertension 1996; 27: 1046–52

Haffner SM, Lehto S, Rönnemaa T, et al. Mortality from coronary heart disease in subjects with type 2 diabetes and in nondiabetic subjects with and without prior myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 1998; 339: 229–34

Ho JE, Paultre F, Mosca L. Women’s Pooling Project. Is diabetes mellitus a cardiovascular disease risk equivalent for fatal stroke in women? Data from the Women’s Pooling Project. Stroke 2003; 34: 2812–6

Candido R, Srivastava P, Cooper ME, et al. Diabetes mellitus: a cardiovascular disease. Curr Opin Investig Drugs 2003; 4: 1088–94

Lee CD, Folsom AR, Pankow JS, et al. Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study Investigators. Cardiovascular events in diabetic and nondiabetic adults with or without history of myocardial infarction. Circulation 2004; 109: 855–60

Juutilainen A, Lehto S, Rönnemaa T, et al. Type 2 diabetes as a ‘coronary heart disease equivalent’: an 18-year prospective population-based study in Finnish subjects. Diabetes Care 2005; 28: 2901–7

Vongpatanasin W. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in high-risk populations: epidemiology and opportunities for risk reduction. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2007; 9 Suppl. 4: 11–5

Rydén L, Standl E, Bartnik M, et al. Guidelines on diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases: executive summary. The Task Force on Diabetes and Cardiovascular Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Eur Heart J 2007; 28: 88–136

Buse JB, Ginsberg HN, Bakris GL, et al. Primary prevention of cardiovascular diseases in people with diabetes mellitus: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association and the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2007 Jan; 30(1): 162–72

Guidelines on diabetes, pre-diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases: executive summary. The Task Force on Diabetes and Cardiovascular Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Eur Heart J 2007; 28: 88-136

New Zealand Guidelines. Evidence-based best practice guidelines: assessment and management of cardiovascular risk. Wellington (NZ): New Zealand Guidelines Group, 2003

The Royal College of General Practitioners. Effective Clinical Practice Unit. Sheffield/NICE: Clinical guidelines for type 2 diabetes: blood pressure man-agement/lipid management. London: National Institute for Clinical Excellence, 2002 Oct

Rose G, Blackburn H. Cardiovascular survey methods. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1968

Classificazione delle Malattie, Traumatismi e Cause di Morte. IX Revisione 1975. Roma: Istituto Centrale di Statistica, Metodi e Norme Serie C, N.10, 1984

BMDP. Statistical software manual. Cork, Ireland: BMDP, 1992

Riscard 2002. Software per la stima del rischio cardiovascolare. Roma: Cardioricerca ed, 2002

Menotti A, Lanti M, Puddu PE, et al. The risk functions incorporated in Riscard 2002: a software for the prediction of cardiovascular risk in the general population based on Italian data. Ital Heart J 2002; 3: 114–21

CCM: il progretto cuore [online]. Available from URL: http://www.cuore.iss.it [Accessed 2007 Sep 1]

Carta del Rischio Cardiovascolare Globale. Progetto Cuore. Istituto Superiore di Sanità, Dicembre 2003 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.cuore.iss.it [Accessed 2007 Sep 1]

Giampaoli S, Palmieri L, Chiodini P, et al. La carta del rischio cardiovascolare globale. Ital Heart J Suppl 2004; 5(3): 177–85

Il Progetto Cuore: Studi Longitudinali. Ital Heart J 2004; 5 Suppl. 3: 94S-101S

Ridker PM, Rifai N, Cook NR, et al. Non-HDL cholesterol, apoliproteins A-I and B100, standard lipid measures, lipid ratios, and CRP as risk factors for cardiovascular disease in women. JAMA 2005; 294: 325–33

Chapman J. Beyond LDL-cholesterol reduction: the way ahead in managing dyslipidaemia. Eur Heart J Suppl 2005; Suppl. F: F56–62

Barter PH, Rye KA. High density cholesterol: the new target. A handbook for clinicians. Birmingham (UK): Sherborne Gibbs Ltd, 2005

Carlson LA. Niaspan: the prolonged release preparation of nicotinic acid (niacin), the broad-spectrum lipid drug. Int J Clin Pract 2004; 58: 706–13

Acknowledgments

Sheridan Henness and Siobhan Ward of Wolters Kluwer Health Medical Communications provided English language assistance and advice on the preparation of this article for submission. Funding for this assistance was provided by Merck Sharp & Dohme, Italy.

The activity of the Research Group for the Estimate of Cardiovascular Risk in Italy and the production of the chart and of this report were sponsored by a scientific-educational grant from Merck Sharpe & Dohme, Italy, based in Rome.

At the time of the research, the Group included Enrico Agabiti-Rosei (University of Brescia, Italy), Gianfranco Botta (MSD Italy, Rome, Italy), Luigi Carratelli (MSD, Rome, Italy), Giuseppe Cavera (Villa Sofia Hospital, Palermo, Italy), Ada Dormi (University of Bologna, Italy), Antonio Gaddi (University of Bologna, Italy), Mariapaola Lanti (Association for Cardiac Research, Rome, Italy), Mario Mancini (University of Naples, Italy), Alessandro Menotti (Association for Cardiac Research, Rome, Italy) Mario Motolese (Centro per la Lotta contro l’Infarto, Rome, Italy), Maria Lorenza Muiesan (University of Brescia, Italy), Sandro Muntoni (University of Cagliari, Italy), Sergio Muntoni (Association MEDICO, Cagliari, Italy), Alberto Notarbartolo (University of Palermo, Italy), Pierluigi Prati (Centro per la Lotta contro l’Infarto, Rome, Italy), Stefano Remiddi (MSD Italy, Rome, Italy), Alberto Zanchetti (University of Milan, Italy)

The prototype of the chart was created by Medrisk srl, Rome, Italy (medrisk@tin.it).

Part of the data reported here were published, in Italian, in the proceedings of the Congress “Conoscere e Curare il Cuore 2007,” organized in Florence, Italy by the Centro per la Lotta contro l’Infarto, Rome, Italy.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Structure of the Chart

Structure of the Chart

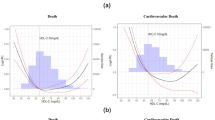

The chart (see figures A1, A2, A3, A4, A5, and A6) allows the estimation of the 10-year risk of developing a first major cardiovascular event in cardiovascular- and diabetes-free subjects as a function of the six chosen risk factors.

Estimation of the 10-year risk (as a function of six risk factors) of developing a first major cardiovascular event using Italian population data, in women aged (a) 45–49 years and (b) 50–54 years. 1 Represents the 10-year relative risk of a major cardiovascular event compared with a person at average risk, for the same sex and age class.

Estimation of the 10-year risk (as a function of six risk factors) of developing a first major cardiovascular event using Italian population data, in women aged (a) 55–59 years and (b) 60–64 years. 1 Represents the 10-year relative risk of a major cardiovascular event compared with a person at average risk, for the same sex and age class.

Estimation of the 10-year risk (as a function of six risk factors) of developing a first major cardiovascular event using Italian population data, in women aged (a) 65–69 years and (b) 70–74 years. 1 Represents the 10-year relative risk of a major cardiovascular event compared with a person at average risk, for the same sex and age class.

Estimation of the 10-year risk (as a function of six risk factors) of developing a first major cardiovascular event using Italian population data, in men aged (a) 45–49 years and (b) 50–54 years. 1 Represents the 10-year relative risk of a major cardiovascular event compared with a person at average risk, for the same sex and age class.

Estimation of the 10-year risk (as a function of six risk factors) of developing a first major cardiovascular event using Italian population data, in men aged (a) 55–59 years and (b) 60–64 years. 1 Represents the 10-year relative risk of a major cardiovascular event compared with a person at average risk, for the same sex and age class.

Estimation of the 10-year risk (as a function of six risk factors) of developing a first major cardiovascular event using Italian population data, in women aged (a) 65–69 years and (b) 70–74 years. 1 Represents the 10-year relative risk of a major cardiovascular event compared with a person at average risk, for the same sex and age class.

The chart has been built creating a number of cells offering all the possible combinations of the six risk factors, subdivided in classes, as follows: two classes for sex (males and females); six classes for age (45–49; 50–54; 55–59; 60–64; 65–69; 70–74 years); four classes for cigarette smoking (0; 1–9; 10–19; ≥20 cigarettes per day); four classes of systolic blood pressure (<129; 130–149; 150–169; ≥170 mmHg); five classes of total cholesterol (<180; 200–219; 220–259; 260–299; ≥300 mg/dL); four classes of HDL-C (<30; 30–39; 40–49; ≥50 mg/dL). For age, the central values of the several classes are 47.5, 52.5, 57.5, 62.5, 67.5, and 72.5 years. For cigarette consumption, the central values of the classes are 0, 5, 15, and 25 cigarettes per day. For systolic blood pressure, the central values of the classes are 120, 140, 160, and 180 mmHg. For total cholesterol, the central values of the classes are 160, 200, 240, 280, and 320 mg/dL. For HDL-C, the central values of the classes are 25, 35, 45, and 55 mg/dL. Estimates of risk for each cell have been made using the central value of each class.

The estimate of the absolute risk was distributed in a number of cells, separately for men and women, with different colors corresponding to the following classes of risk: <5% in 10 years; 5–9%; 10–14%; 15–19%; 20–29%, ≥30%. In the original chart, another parallel series of cells was produced with the estimate of the so called ‘relative risk,’ that is the ratio between the observed (absolute) risk and that of a person of the same sex and age, carrying the mean sex- and age-specific levels of risk factors in the general population. The relative risk, labelled with a number of different colors, was classified as <1 time; 1–2 times; 2–3 times; 3–4 times, 4–5 times; and ≥5 times, referred to the reference subject. These levels represent multiples of risk compared with a person at average risk, for the same sex and age class. Because of this special feature, the relative risk section is reproduced here.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Menotti, A., Lanti, M. An Italian Chart for Cardiovascular Risk Estimate Including High-Density Lipoprotein-Cholesterol. Dis-Manage-Health-Outcomes 16, 183–197 (2008). https://doi.org/10.2165/00115677-200816030-00005

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00115677-200816030-00005