Abstract

Background

A disturbance in eating behaviour (EB) is the hallmark of patients with eating disorders, and depicts a complex interaction of environmental, psychological and biological factors. In the present study, we propose a model of association of genetic susceptibility—represented by adiponectin (ADIPOQ) gene—with eating behavioural and psychological traits.

Results

Evaluation of the distribution of a polymorphism of the ADIPOQ (rs1501299 G > T) with respect to three EB factors involving cognitive restraint, uncontrolled eating and emotional eating revealed that T-allele in rs1501299 was associated with a decreased susceptibility to emotional EB in codominant (e.g., GG vs. TT) (beta-coefficient [β] = 2.39, 95% Confidence interval [CI] = − 4.02, − 0.76; p value [p] = 0.02), recessive (GG + GT vs. TT) (β = − 2.77, 95% CI = − 3.65, − 0.69; p = 0.005) and additive (GG = 0, GT = 1, TT = 2) (β = − 1.02, 95% CI = − 1.80, − 0.24; p = 0.01) models of inheritance. The presence of the T-allele was not significantly associated with psychological factors involving depression, anxiety and stress. Finally, none of the psychological traits significantly predicted any of the EB factors after controlling for age, body weight and gender.

Conclusions

Our data suggest that genetic variant in ADIPOQ locus may influence human emotional eating behaviour.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The cognitive, behavioural and emotional aspects of eating habit encompass environmental, psychological and biological factors (LaCaille 2013). According to a gene—environmental approach, the different aspect of the eating behaviour can be influenced by genetic variability, explaining a part of the variance of the contribution to eating behaviours and different phenotypical features (Tholin et al. 2005). In this view, several genes have been investigated as possible candidates (Grimm and Steinle 2011). Among these, great interest has been recently devoted to genes encoding adiponectin pathway (Awofala et al. 2019; Christodoulou et al. 2020).

Adiponectin (ADIPOQ) is an adipocyte secreted 247—amino acid peptide that circulates in large amount in plasma (Ghadge et al. 2018; Martin 2014) and is involved in multiple functions such as insulin sensitization, cardioprotection, and anti-inflammatory processes (Berg et al. 2001; Ouchi et al. 2006; Yamauchi et al. 2007). Circulating adiponectin plays a potential role in the regulation of feeding behaviour and in energy homeostasis (Qi et al. 2004; Kubota et al. 2007), and appears to be related to psychological functioning. Indeed, altered levels of adiponectin have been found in eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa, binge eating disorder and bulimia nervosa (Khalil and Hachem 2014) and in several other psychiatric conditions including depression and anxiety disorders (Wędrychowicz et al. 2014; Carvalho et al. 2014).

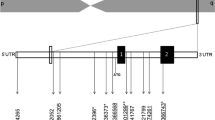

Among ADIPOQ single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), the SNP, rs1501299 (+ 276G/T in intron 2 on chromosome 3) is perhaps one of the most studied of the common ADIPOQ gene variant; studies have linked rs1501299 with circulating adiponectin and cardiometabolic consequences of obesity such as type 2 diabetes, insulin resistance and cardiovascular risk (Hara et al. 2002; Jang et al. 2005, 2006; de Luis et al. 2016). The T-allele in ADIPOQ rs1501299 was associated with increased insulin levels and decreased circulating adiponectin (de Luis et al. 2016). However, it has neither been investigated if the SNP is involved in human eating behaviour nor psychological traits, particularly in Nigerians.

Studies assessing genetic and environmental influences in EB using the original Three Factor Eating Questionnaire (TFEQ) (Stunkard and Messick 1985), a widely used self-assessment instrument that measures 3 domains: cognitive restraint, hunger, and disinhibition have shown that genetics has important effects on EB (Steinle et al. 2002; Rohde et al. 2015). An earlier US family study which included 624 Amish men and women reported 28%, 40%, and 23% as heritability estimates of restraint, disinhibition, and hunger (Steinle et al. 2002). A more recent German study, which included 548 Sorbs and 350 replication German cohort found that 3 variants in adiponectin gene were nominally significantly associated with hunger (rs2036373) and disinhibition (rs822396, rs864264) based on additive model of inheritance (Rohde et al. 2015). Interestingly, study has recently shown that elevated blood adiponectin level is causally related to eating disinhibition in central European population (Awofala et al. 2019). Of note, as the original factor structure of TFEQ could not be replicated in several studies (Karlsson et al. 2000; Mazzeo et al. 2003), a refined 18—item version (TFEQ-R81) (Khalil and El Hachem 2014) was used in the present study.

Investigation of the genetic influence of EB and the associated psychobehavioural traits is important for extending our understanding of food intake regulation and energy balance as well as in the pathophysiology of eating disorders. Our aim was to evaluate the role of adiponectin gene on EB in a Nigerian cohort of young adults.

Methods

Study design

This was a cross-sectional study at a public university.

Study population

The sample cohort included 560 healthy young adults of Nigerian descent. Participants were extensively phenotyped for a wide range of anthropometric, eating behavioural and psychological traits including weight, height, depression, anxiety, stress, and cognitive, behavioural and emotional aspects of eating habits using clinical instruments and standardized questionnaires. The anthropometric assessment is described more in depth from a previous publication (Ogundele et al. 2018). Genetic information was available for 78 of these participants.

Assessments

A total of 555 participants with mean age of 21.5 ± 2.9 years and mean BMI 20.8 ± 5.4 kg/m2 completed the revised Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire (TFEQ-R18) scale (Karlssson et al. 2000). The TFEQ-R18 covers 3 EB domains: the 9-item uncontrolled eating scale that was constructed from the hunger (6 items) and disinhibition (3 items) scales of the original TFEQ and assesses the tendency to lose control over eating when feeling hungry or when exposed to external stimuli; the 6-item cognitive restraint scale that assesses control over food intake to influence body weight and body shape; and, the 3-item emotional eating scale that was constructed from items included in the disinhibition scale, measures the propensity to eat in response to a range of negative emotions such as anxiety, depression and anger. Although constructed using data from obese adults, TFEQ-R18 has been shown to be applicable to other populations (De Lauzon et al. 2004; Anglé et al. 2009), and was satisfactorily replicated in the present study sample (unpublished data).

Participants also completed the short version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS-21; Lovibond and Lovibond 1996). The scale has been translated and validated in many languages with excellent values of reliability, and strong internal consistency in several ethnic groups for both adults and adolescents (Szabó 2010; Oei et al. 2013; Tonsing 2014), and covers 3 broad spectrums of psychological symptoms involving depression, anxiety and stress, and with each containing a 7-item sub-scales that measure the frequency and severity of each symptom or trait in clinical and non-clinical sample. In our study, the Cronbach α internal-consistency reliability for each of the 7-item scores was satisfactorily high in depression (α = 0.78), anxiety (α = 0.81) and stress (α = 0.73) scales.

Genetic analysis

Genotyping of ADIPOQ rs1501299 G/T (+ 276G > T) was performed as described previously (Kubota et al. 2007). Genomic deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) was isolated from dried blood spot (DBS) samples of 78 participant using Zymo Research (ZR) DNA Card Extraction Kits according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The genotyping reaction was performed with SNP-specific polymerase chain reaction using single-base primer extension technology (Sequenom MassARRAY Genotyping System (Sequenom, San Diego, CA, USA) based on the method described by Yue and colleagues (Yu et al. 2015). The genotyping efficiency was > 92%.

Statistical analysis

Variables were reported as means ± SD. The independent sample t test was used to compare gender groups on the whole sample (N = 555). Relationships of BMI with EB and psychological traits and between psychological components and eating behaviour were established using the Pearson’s correlation coefficient test. The overall associations of ADIPOQ genotypes (GG, GT, TT) with EB phenotypes and psychological traits were tested. To comprehensively analyse the association between the exposure and the outcomes, genotype analyses were performed assuming codominant (GG vs. GT vs. TT), recessive (GG + GT vs. TT), and multiplicative or additive (GG = 0, GT = 1, TT = 2) models by means of linear regression adjusting for gender. As ADIPOQ rs1501299 G/T genotype was available for 78 participants in this study, a complete case genotype analysis was carried out on the sample. Independent sample t test was performed to evaluate BMI, EB scores, and psychological trait scores differences in the participants with different ADIPOQ genotypes. General Linear Model (GLM) was also adopted to test the relationship between psychological trait scores and the three eating behavioural phenotypes adjusting for age, gender and BMI. All statistical analyses were implemented in statistical analysis system (SAS) version 9.2.1.

Results

The demographic and clinical characteristics of male and female participants are reported in Table 1. Female participants were more likely to be younger (21.4 ± 2.6 vs. 22.1 ± 3.0; t = 2.66, p = 0.008) and had higher BMI (21.5 ± 4.5 vs. 18.1 ± 5.2; t = 2.63, p = 0.01) than their male counterparts. Other comparisons between gender groups were not significant.

Correlational analysis of BMI with eating behavioural phenotypes and psychological traits revealed uncontrolled eating as the only TFEQ-R18 scale that was significantly correlated with BMI (r = − 0.27, p = 0.02). None of the psychological traits was significantly correlated with BMI. Of note however, significant positive correlations of emotional eating scale (r = 0.33–0.42, p < 0.001) and uncontrolled eating scale (r = 0.35–0.36, p < 0.001) with depression, anxiety and stress psychological trait scales were observed.

The distributions of genotypes of rs1501299 with respect to the 3 eating behavioural phenotypes are presented in Table 2. In the codominant models, participants with less frequent TT genotypes were less likely to develop emotional EB when compared with those with more frequent GG genotypes (β = − 2.39, 95% CI = − 4.01, − 0.76; p = 0.02). This observation was recapitulated in the recessive (GG + GT vs. TT) (β = − 2.77, 95% CI = − 3.65, − 0.69; p = 0.005) and additive (GG = 0, GT = 1, TT = 2) (β = − 2.77, 95% CI = − 3.65, − 0.69; p = 0.005) models of inheritance. Notably, none of these genotypes was significantly associated with uncontrolled or cognitive restraint scales of TFEQ-R18.

The comparisons of clinical variables, in relations to rs1501299 polymorphism, are reported in Table 3. G-allele carriers, as compared to TT genotype carriers, reported significantly higher emotional eating scores (5.9 ± 2.4 vs. 3.8 ± 2.4; t = 2.87, p < 0.01).

The genetic association between rs1501299 and psychological traits is shown in Fig. 1. None of the psychological traits was significantly associated to rs1501299 polymorphism.

Finally, General Linear Model showed that none of the psychological traits significantly predicted any of the TFEQ-R18 subscales after controlling for age, BMI and gender (Table 4).

Discussion

In the present study, we evaluated ADIPOQ rs1501299 variant as a risk factor for eating behavioural phenotypes and their associated psychobehavioural traits. The main findings are that the minor allele carrier in ADIPOQ rs1501299 (G > T) variant is significantly associated with a decreased emotional EB but not cognitive and uncontrolled EB factors. This significantly decreased in emotional EB, which indicate individuals’ lower eating responses, was not influenced by psychobehavioural factors, as no significant association between ADIPOQ rs1501299 SNP and psychological traits was found. Moreover, none of the psychological traits significantly predicted EB factors after controlling for age, sex and body weight.

The emotional eating scale of the TFEQ-R18 depicts a measure of overeating induced by negative mood and emotions, and indicates individuals’ tendencies to overeat as opposed to appetite loss when experiencing negative emotions (e.g., fear, anxiety, depression or anger). Thus, emotional eaters have difficulties in distinguishing between the psychological states of negative emotions on one hand and hunger-satiety on the other. Interestingly, our results indicate that emotional eating as measured by the TFEQ-R18 is influenced by the T- allele in ADIPOQ rs1501299 (G > T). This suggests that persons with less frequent TT genotypes exhibit lower emotionally induced eating than do those with more frequent GG genotypes. Importantly, that this study showed genetic association with only emotional EB but not others may indicate genetic dissociation among the 3 eating behavioural traits. In support of this, two earlier female twin studies found genetic influences on only the disinhibition scale of the original TFEQ (Mazzeo et al. 2003; Neale et al. 2003), which may be comparable with our results for emotional eating. In addition, an observational study of the role of adiponectin in EB (Rohde et al. 2015) showed that genetic polymorphisms in ADIPOQ were related to disinhibition and hunger scales of the original TFEQ. A more recent study from our group indicated that the observational association between the effect allele carriers in the ADIPOQ SNPs showing elevated adiponectin serum levels along with eating disinhibition was causal (Awofala et al. 2019). Of note, the disinhibition scale evaluates impulsive eating in response to emotional, cognitive and social cues. Indeed, items of the TFEQ-R18 emotional eating scale were derived from the original TFEQ disinhibition scale.

It is particularly noteworthy that the direction of association between adiponectin and eating behaviours reported in the studies reviewed above differs in our present study. The opposite relationship can in part be explained by the use of ADIPOQ SNPs other than the one in the present study. In addition, it appears that factors that make up the disinhibition scale (i.e., emotional, cognitive and social factors) need to be disentangled to found out if they have specific relationship to adiponectin gene. Nevertheless, the observed association between ADIPOQ rs1501299 (G > T) variant and decreased emotional EB seems to correlate well with known roles of the minor T allele at ADIPOQ rs1501299 G/T polymorphism in adiponectin levels and insulin resistance: T allele was associated with high levels of adiponectin and insulin sensitivity in non-diabetic men (Hivert et al. 2008). However, subjects with the T allele at rs1501299 showed significantly lower high-density lipoprotein (HDL)-cholesterol and higher brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity (baPWV) leading to an increase in arterial stiffness in essential hypertensive patients (Kawai et al. 2013). The latter discrepancy among the study results may be due to several factors such as differences in study design and subject characteristics as well as diversities in basic metabolic health status and genetic properties. Our study subjects were young adults without any history of disease or medication.

We have previously shown that ADIPOQ rs1501299 (G > T) variant was not significantly correlated to several measures of obesity in young Nigerian adults (Kubota et al. 2007). However, on the basis of the results presented above, it is clear that EB is influenced at least in part by adiponectin gene. It thus appears that some genetic variants affecting EB may to a certain extent not be involved in the development of obesity. Indeed, several variants of ADIPOQ studied in relation to obesity have produced inconsistent results across different populations (Ukkola et al. 2005; Hivert et al. 2008; Cohen et al. 2011; Kaur et al. 2018). Notably however, several studies in which TFEQ-RI8 was used as a measure of EB have reported close associations of emotional eating and cognitive restraint scales with BMI (Elfhag and Linné 2005; de Lauzon-Guillain et al. 2006; Anglé et al. 2009). In the present study, only scores on the uncontrolled eating scale were significantly associated with BMI in the univariate analysis; this association failed to reach statistical significance in the adjusted model. Indeed, it appears higher body weight make people eat differently (Anglé et al. 2009). A 2-year follow-up French study by de Lauzon-Guillain et al. (2006) indicated that initial scores of cognitive restraint were not connected with subsequent adiposity changes in either adults or adolescents; however, in all age groups studied, higher values of initial adiposity including BMI predicted a larger increase in cognitive restraint score over the two year period. Moreover, findings from a Swedish young male twin study indicated that obese individuals exhibited more emotionally induced eating than do non-obese ones (Tholin et al. 2005).

Several studies have reported the correlation between circulating adiponectin and psychological factors, particularly depression, anxiety and stress (Carvalho et al. 2014; Diniz et al. 2012; Unsal et al. 2012). Low levels of adiponectin were found in several psychiatric conditions, including severe depression (Carvalho et al. 2014; Diniz et al. 2012) and anxiety disorders (Unsal et al. 2012). In addition, higher levels of adiponectin were significantly related to lower self-ratings of depression and anxiety but stress in patients with anorexia nervosa during inpatient treatment (Buckert et al. 2017). In this cross-sectional study in a young Nigerian population, we did not see any significant association between ADIPOQ rs1501299 and psychological factors. In addition, our study observed relationship between psychological traits and EB that failed to reach statistical significance in the adjusted model. Though adiponectin gene is a known predictor of adiponectin concentrations in several populations (Hivert et al. 2008; Cohen et al. 2011; Tanimura et al. 2011; de Luis et al. 2016), we have no serum adiponectin levels available in the present study to confirm this in the young Nigerian population. Further studies are thus warranted to shed more light on the complexity of our results.

This study is limited in several respects. First, we are aware that the significant results presented could prove to be false positives because of the small sample size, and as such further studies using larger sample are warranted. It should be noted that due to our small sample size, we were unable to carry out rigorous stratify analysis to further shed light on the veracity of our results. However, with larger sample, the functional and biological relevance of the described variant would require further study. In addition, our results cannot be easily generalized to older adults and other ethnic groups in Nigeria. Further, we did not run a replication study neither did have available serum adiponectin levels that could add validity to our results. Notwithstanding these limitations, the earlier interpretations of our results should enable the reader to reach a reasonable conclusion.

In conclusion, the present study suggests that the T allele at ADIPOQ rs1501299 G/T polymorphism represents a putative protective factor for young people to reduce their emotional EB. Hence, the present results may prove to be useful for personal-based early prevention and management of pathological EB factors such as binge eating.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ADIPOQ:

-

Adiponectin gene

- baPWV:

-

Brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- DASS:

-

Depression anxiety scale

- DBS:

-

Dried blood spot

- DNA:

-

Deoxyribonucleic acid

- EB:

-

Eating behaviour

- GLM:

-

General linear model

- GWAS:

-

Genome-wide association studies

- HDL:

-

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- SAS:

-

Statistical analysis system

- SE:

-

Standard error

- SNP:

-

Single-nucleotide polymorphisms

- TFEQ:

-

Three-factor eating questionnaire

- ZR:

-

Zymo research

References

Anglé S, Engblom J, Eriksson T, Kautiainen S, Saha MT, Lindfors P, Lehtinen M, Rimpelä A (2009) Three factor eating questionnaire-R18 as a measure of cognitive restraint, uncontrolled eating and emotional eating in a sample of young Finnish females. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 6(1):41

Awofala AA, Ogundele OE, Adekoya KO, Osundina SA (2019) Adiponectin and human eating behaviour: a Mendelian randomization study. Egypt J Med Hum Genet 20(1):17

Berg AH, Combs TP, Du X, Brownlee M, Scherer PE (2001) The adipocyte-secreted protein Acrp30 enhances hepatic insulin action. Nat Med 8:947–953

Buckert M, Stroe-Kunold E, Friederich HC, Wesche D, Walter C, Kopf S, Simon JJ, Herzog W, Wild B (2017) Time course of adiponectin and its relationship to psychological aspects in patients with anorexia nervosa during inpatient treatment. PLoS ONE 12(12):e0189500

Carvalho AF, Rocha DQC, McIntyre RS, Mesquita LM, Koehler CA, Hyphantis TN et al (2014) Adipokines as emerging depression biomarkers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Res 59:28–37

Christodoulou A, Ierodiakonou D, Awofala AA, Petrou M, Kales SN, Christiani DC et al (2020) Variants in ADIPOQ gene are linked to adiponectin levels and lung function in young males independent of obesity. PLoS ONE 15(1):e0225662

Cohen SS, Gammon MD, North KE, Millikan RC, Lange EM, Williams SM et al (2011) ADIPOQ, ADIPOR1, and ADIPOR2 polymorphisms in relation to serum adiponectin levels and body mass index in black and white women. Obesity 19(10):2053–2062

De Lauzon B, Romon M, Deschamps V, Lafay L, Borys J-M (2004) The three-factor eating questionnaire-R18 is able to distinguish among different eating patterns in a general population. J Nutr 134:2372–2380

de Lauzon-Guillain B, Basdevant A, Romon M, Karlsson J, Borys J-M, Charles MA (2006) Is restrained eating a risk factor for weight gain in a general population? Am J Clin Nutr 83:132–138

de Luis DA, Izaola O, de la Fuente B, Primo D, Ovalle HF, Romero E (2016) rs1501299 polymorphism in the adiponectin gene and their association with total adiponectin levels, insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome in obese subjects. Ann Nutr Metab 69(3–4):226–231

Diniz BS, Teixeira AL, Campos AC, Miranda AS, Rocha NP, Talib LL et al (2012) Reduced serum levels of adiponectin in elderly patients with major depression. J Psychiatr Res 46(8):1081–1085

Elfhag K, Linné Y (2005) Gender differences in associations of eating pathology between mothers and their adolescent offspring. Obes Res 13:1070–1076

Ghadge AA, Khaire AA, Kuvalekar AA (2018) Adiponectin: a potential therapeutic target for metabolic syndrome. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 39:151–158

Grimm ER, Steinle NI (2011) Genetics of eating behavior: established and emerging concepts. Nutr Rev 69(1):52–60

Hara K, Boutin P, Mori Y, Tobe K, Dina C, Yasuda K et al (2002) Genetic variation in the gene encoding adiponectin is associated with an increased risk of type 2 diabetes in the Japanese population. Diabetes 51:536–540

Hivert MF, Manning AK, McAteer JB, Florez JC, Dupuis J, Fox CS et al (2008) Common variants in the adiponectin gene (ADIPOQ) associated with plasma adiponectin levels, type 2 diabetes, and diabetes-related quantitative traits: the Framingham Offspring Study. Diabetes 57(12):3353–3359

Jang Y, Lee JH, Chae JS, Kim OY, Koh SJ, Kim JY et al (2005) Association of the 276G>T polymorphism of the adiponectin gene with cardiovascular disease risk factors in nondiabetic Koreans. Am J Clin Nutr 82:760–767

Jang Y, Lee JH, Kim OY, Koh SJ, Chae JS, Woo JH et al (2006) The SNP276G>T polymorphism in the adiponectin (ACDC) gene is more strongly associated with insulin resistance and cardiovascular disease risk than SNP45T>G in nonobese/nondiabetic Korean men independent of abdominal adiposity and circulating plasma adiponectin. Metab Clin Exp 55:59–66

Karlsson J, Persson LO, Sjöström L, Sullivan M (2000) Psychometric properties and factor structure of the Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire (TFEQ) in obese men and women. Results from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) study. Int J Obes 24(12):1715

Kaur H, Badaruddoza B, Bains V, Kaur A (2018) Genetic association of ADIPOQ gene variants (-3971A > G and+ 276G> T) with obesity and metabolic syndrome in North Indian Punjabi population. PLoS ONE 13(9):e0204502

Kawai T, Ohishi M, Takeya Y, Onishi M, Ito N, Yamamoto K, Oguro R, Kamide K, Rakugi H (2013) Adiponectin single nucleotide polymorphism is a genetic risk factor for stroke through high pulse wave pressure: a cohort study. J Atheroscler Thromb 20(2):152–160

Khalil RB, El Hachem C (2014) Adiponectin in eating disorders. Eat Weight Disord 19(1):3–10

Kubota N, Yano W, Kubota T, Yamauchi T, Itoh S, Kumagai H et al (2007) Adiponectin stimulates amp-activated protein kinase in the hypothalamus and increases food intake. Cell Metab 6(1):55–68

LaCaille L (2013) Eating behavior. In: Gellman MD, Turner JR (eds) Encyclopedia of behavioral medicine. Springer, New York

Lovibond SH, Lovibond PF (1996) Manual for the depression anxiety stress scales, 2nd edn. Sydney Psychology Foundation of Australia

Martin LJ (2014) Implications of adiponectin in linking metabolism to testicular function. Endocrine 46:16–28

Mazzeo SE, Aggen SH, Anderson C, Tozzi F, Bulik CM (2003) Investigating the structure of the eating inventory (three-factor eating questionnaire): a confirmatory approach. Int J Eat Disord 34:255–264

Neale BM, Mazzeo SE, Bulik CM (2003) A twin study of dietary restraint, disinhibition and hunger: an examination of the eating inventory (three factor eating questionnaire). Twin Res 6:471–478

Oei TP, Sawang S, Goh YW, Mukhtar F (2013) Using the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale 21 (DASS-21) across cultures. Int J Psychol 48(6):1018–1029

Ogundele OE, Adekoya KO, Osinubi AA, Awofala AA, Oboh BO (2018) Association of adiponectin gene (ADIPOQ) polymorphisms with measures of obesity in Nigerian young adults. Egypt J Med Hum Genet 19(2):123–127

Ouchi N, Shibata R, Walsh K (2006) Cardioprotection by adiponectin. Trends Cardiovasc Med 16(5):141–146

Qi Y, Takahashi N, Hileman SM, Patel HR, Berg AH, Pajvani UB et al (2004) Adiponectin acts in the brain to decrease body weight. Nat Med 10(5):524–529

Rohde K, Keller M, Horstmann A, Liu X, Eichelmann F, Stumvoll M, Villringer A, Kovacs P, Tönjes A, Böttcher Y (2015) Role of genetic variants in ADIPOQ in human eating behavior. Genes Nutr 10(1):1

Steinle NI, Hsueh WC, Snitker S, Pollin TI, Sakul H, St Jean PL, Bell CJ, Mitchell BD, Shuldiner AR (2002) Eating behavior in the Old Order Amish: heritability analysis and a genome-wide linkage analysis. Am J Clin Nutr 75(6):1098–1106

Stunkard AJ, Messick S (1985) The three-factor eating questionnaire to measure dietary restraint, disinhibition and hunger. J Psychosom Res 29(1):71–83

Szabó M (2010) The short version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): factor structure in a young adolescent sample. J Adolesc 33(1):1–8

Tanimura D, Shibata R, Izawa H, Hirashiki A, Asano H, Murase Y, Miyata S, Nakatochi M, Ouchi N, Ichihara S, Yasui K (2011) Relation of a common variant of the adiponectin gene to serum adiponectin concentration and metabolic traits in an aged Japanese population. Eur J Hum Genet 19(3):262

Tholin S, Rasmussen F, Tynelius P, Karlsson J (2005) Genetic and environmental influences on eating behavior: the Swedish Young Male Twins Study. Am J Clin Nutr 81(3):564–569

Tonsing KN (2014) Psychometric properties and validation of Nepali version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21). Asian J Psychiatr 8:63–66

Ukkola O, Santaniemi M, Rankinen T, Leon AS, Skinner JS, Wilmore JH et al (2005) Adiponectin polymorphisms, adiposity and insulin metabolism: HERITAGE family study and Oulu diabetic study. Ann Med 37(2):141–150

Unsal C, Hariri AG, Yanartas O, Sevinc E, Atmaca M, Bilici M (2012) Low plasma adiponectin levels in panic disorder. J Affect Disord 139(3):302–305

Wędrychowicz A, Zając A, Pilecki M, Kościelniak B, Tomasik PJ (2014) Peptides from adipose tissue in mental disorders. World J Psychiatry 4(4):103–111

Yamauchi T, Nio Y, Maki T, Kobayashi M, Takazawa T, Iwabu M et al (2007) Targeted disruption of AdipoR1 and AdipoR2 causes abrogation of adiponectin binding and metabolic actions. Nat Med 13(3):332–339

Yu Z, Li W, Hou D, Zhou L, Deng Y, Tian M, Feng X (2015) Relationship between adiponectin gene polymorphisms and late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS ONE 10(4):e0125186

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all our enthusiastic study participants.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AAA conceived the study, conducted the analysis and drafted the manuscript. OEO took part in the study design, data generation and analysis plan. KOA provided technical and material support and assisted in the analysis plan. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The present study was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Study procedures were fully explained to participants prior to collection of data; after which participants were asked to sign written informed consent for participation in the study and for genetic analysis. This study protocol was approved by the Health Research Ethics Committee (HREC) of Lagos University Teaching Hospital (LUTH) in the University of Lagos (protocol number: ADM/DCST/HREC/APP/80).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Awofala, A.A., Ogundele, O.E. & Adekoya, K.O. ADIPOQ gene is linked to emotional eating behaviour in young Nigerian adults independent of psychological traits. Bull Natl Res Cent 44, 195 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42269-020-00450-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s42269-020-00450-5