Abstract

Background

According to the World Health Organization, Nigeria is one of the countries with a high burden of tuberculosis (TB) worldwide. Improving the burden of TB among HIV-negative people would require comprehensive and up-to-date data to inform targeted policy actions in Nigeria. The study aimed to describe the incidence, prevalence, mortality, disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) and risk factors of tuberculosis in Nigeria between 1990 and 2016.

Methods

This study used the most recent data from the global burden of disease study 2016. TB deaths were estimated using the Cause of Death Ensemble model, while TB incidence, prevalence and DALYs, as well as years of life lost and years of life lived with disability were calculated in the DisMod-MR 2.1, a Bayesian meta-regression tool. Using a comparative risk assessment approach, TB burden attributable to risk factors was estimated in a spatial-temporal Gaussian Process Regression tool.

Results

In 2016, the prevalence of TB among HIV-negative people was 27% (95% uncertainty interval [95% UI] 23–31%) in Nigeria. TB incidence rate (new and relapse cases) was 158 per 100,000 people (95% UI; 128-193), while the total number of TB mortality was 39,933 deaths (95% UI; 30,488-55,039) in 2016. Between 2000 and 2016, the age-standardised prevalence and incidence rates of TB-HIV negative decreased by 20.0 and 87.6%, respectively. The age-standardised mortality rate also dropped by 191.6% over the same period. DALYs due to TB among HIV-negative Nigerians was high but varied across the age groups. Of the risk factors studied, alcohol use accounted for the highest number of TB deaths and DALYs, followed by diabetes and smoking in 2016.

Conclusion

The study shows an improving trend in TB disease burden among HIV-negative individuals in Nigeria from 1990 to 2016. Despite this progress, this study suggests that additional efforts are still needed to ensure that Nigeria is not left behind in the current global strategy to end TB disease. Reducing TB disease burden in the country will require a multipronged approach that includes increased funding, health system strengthening and improved TB surveillance, as well as preventive efforts for alcohol use, smoking and diabetes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Tuberculosis (TB) remains a significant public health issue in low-income and middle-income countries and is the leading cause of deaths as a single infectious disease, ranking above human immunodeficiency virus and acquired immune deficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) [1]. The World Health Organization’s (WHO) Global Tuberculosis Report 2017 reported 6.3 million new cases of TB among HIV-negative people in 2016 [1], compared to 6.1 million in 2015 [2]. Similarly, the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries and Risk Factors (GBD) Study 2016 estimated 9.0 million TB-HIV-negative incident cases (new and relapse cases) compared to 8.8 million in 2015 [3]. These reports highlighted the considerable burden of TB globally. For example, the WHO African region accounted for 25% of the total number of incident cases (i.e., TB-HIV-negative and TB-HIV infection) globally, where Nigeria accounted for 8% or 407 cases per 100,000 population in 2016 [1], up from 322 cases per 100,000 population in 2015 [2]. These estimates may be lower than the actual number of TB cases in Nigeria because only less than a quarter of TB cases (15%) were notified in 2015 [2].

In the past two decades, the WHO has listed Nigeria as one of the countries with a high burden of TB in order to stimulate targeted interventions and advocacy for funding and policies to improve TB control [4]. This initiative has led to focused and practical actions for TB control worldwide [1]. Recently, the Nigeria National TB Control Programme and its donor partners have commenced the scale-up of availability and accessibility to improved methods for TB diagnosis and effective treatment regimen [5, 6]. While those efforts are needed and well deserved in Nigeria, there are limited pragmatic policy actions to tackle emerging risk factors for TB at the population level, including diabetes [7, 8], alcohol intake [8,9,10,11] and tobacco smoking [8, 12]. Country-specific epidemiologic studies which investigate trends in TB disease burden and the attributable risk factors for TB would be useful for public health experts and policy-makers to strengthen TB control and preventive efforts.

Evidence shows that TB mortality among HIV-negative people has declined in many developing countries (including Nigeria); but that TB incidence has remained unchanged in many communities [1, 3]. To ensure a continued reduction in TB disease burden in Nigeria, it is essential to understand not only the trends in TB burden but also the extent to which risk factors contribute to TB disease burden to inform targeted and high-priority TB programmes. We have provided a detailed exposition of TB disease burden in Nigeria from the GBD findings because this is not practicable in the GBD capstone publications due to the huge size and scope of the study, which have also led to further characterisation of the results for other health focus areas and locations [3, 13,14,15,16]. Additionally, by distilling the findings for TB burden in Nigeria, we aim to increase awareness and understanding of TB estimates for clinicians, national, and international health experts for TB prevention and control programmes, especially that Nigeria is the largest recipient of developmental assistance for health in Sub-Saharan Africa [17]. The present study aimed to highlight the incidence, prevalence, deaths, disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) and risk factors for tuberculosis in Nigeria from 1990 to 2016 using data from the GBD Study 2016.

Methods

Overview of data sources

The GBD study is a systematic and scientific effort that provides comparable estimates of incidence, prevalence, the cause of death and health loss, and risk factors for diseases and injuries by age, sex, year, location, and over time. In the past two decades, the GBD study has been quantifying health loss from diseases and injuries to inform health programmes and policy decision-making worldwide [18, 19]. The GBD 2016 complied with the Guidelines for Accurate and Transparent Health Estimates Reporting (GATHER) statement, a global agreement that ensures transparency, accurate reporting, interpretation and use of health estimates [20].

For this study, the complete information on data sources, the conceptual framework, and the analytical strategy for the calculation of TB incidence, prevalence, mortality, DALYs and attributable risk factors in Nigeria has been described elsewhere [3, 21,22,23,24,25]. Data used for the TB estimation in Nigeria have been extracted from the Global Health Exchange website (GHDx, http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-2016/data-input-sources). GHDx provides researchers and policy-makers access to the most recent GBD input sources and results, and also creates opportunities for discussing population health based on the best available data, as well as acknowledgment of data owners’ contributions [26].

Case definition

TB is an infectious disease caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis, an acid-fast bacillus that is spread mainly via the respiratory pathway. The GBD study provides estimates for all forms of TB, including pulmonary and extrapulmonary TB using the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) codes [27]. In this study, we have reported estimates for TB (drug-susceptible TB, extensively drug resistance TB, latent TB infection and multidrug-resistant TB, MDR-TB) among HIV-negative people in Nigeria. Information on TB-HIV is provided elsewhere [3, 28].

Overview of the estimation of incidence, prevalence, mortality, disability-adjusted life years and risk factors for tuberculosis

TB mortality was modelled in the GBD Cause of Death Ensemble model (CODEm), a Bayesian, hierarchical, ensemble modelling tool, which has been used to estimate cause-specific mortality for a range of diseases and injuries globally [21, 29]. CODEm modelling strategy used data from the WHO Global Project on Anti-Tuberculosis Drug Resistance Surveillance data (1988–2015) and community-based surveillance data for Nigeria and applied different functional forms (mixed-effects models and spatiotemporal Gaussian process regression models) to mortality rates with varying combinations of predictive models [21].

TB incidence was estimated based on age-specific and sex-specific notification data from the WHO and was defined as new and relapse cases diagnosed within a given calendar year [25]. Categorised notification data (i.e. new pulmonary smear-positive, new pulmonary smear-negative, new extrapulmonary and relapse) were combined to represent all forms of TB [3]. The GBD study estimated point prevalence of TB, defined as the people in the population who at any point within a calendar year with active TB [25].

DALYs are a summary metric of disease or injuries, defined as the number of years lost due to ill-health, disability or premature death, and were computed as the sum of years of life lost (YLLs) and years lived with disability (YLDs) for each year and age in Nigeria [24]. YLLs were calculated by multiplying TB deaths by normative standard life birth (86.9 years), measured as the lowest observed death rates for each 5-year age group in populations higher than five million [30]. In the estimation of YLDs, TB epidemiologic data from the WHO and the Nigeria National Tuberculosis Prevalence Survey 2012 were multiplied by a TB-specific disability weight. The disability weight was obtained from population-based surveys, where respondents rated their health status, from ‘perfect health’ to ‘death’ to quantify the severity of the health loss due to a given disease or injury [24].

TB mortality and DALYs attributable to risk factors were computed as the proportion of deaths and DALYs that could be attributed to risk factors (alcohol use, diabetes and tobacco smoking) as a counterfactual relative to the theoretical minimum level of exposure had the population not been exposed to the given risk factor previously. Based on the available evidence on the causal relationship between risk factors and TB, GBD 2016 estimated the attributable burden of diabetes, alcohol use and tobacco smoking for TB in Nigeria using the comparative risk assessment (CRA) strategy developed by Murray and Lopez [31]. Estimates of the attributable number of deaths or DALYs were calculated by multiplying the number of deaths, or DALYs for the outcome by the population attributable fraction (PAF) for the risk-outcome pair for a given age and year in Nigeria [3].

The analyses were conducted in DisMod-MR 2.1, the GBD meta-regression tool that adjusts for variations in epidemiologic data sources and other parameters, including model predictions, as well as propagates uncertainty around the estimates. DisMod-MR 2.1 also estimated 95% corresponding uncertainty intervals for TB incidence, prevalence, deaths and DALYs. A full description of the analytical strategy for the estimation of TB epidemiology in Nigeria is provided in respective GBD study publications [21,22,23,24,25].

Results

Levels and trends of tuberculosis prevalence, incidence, mortality and DALYs

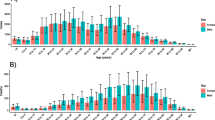

In 2016, age-standardised prevalence rate of TB among HIV-negative people was 31,643.5 per 100,000 population (95% uncertainty interval [95% UI] 27,316-36,249) (Table 1), while the absolute prevalence was 27% (95% UI; 23–31%), highest in people aged 50–69 years and lowest in children under 5 years (Fig. 1). Absolute TB incidence rate (new and relapse cases) was 158 per 100,000 people (95% UI; 128-193) (Table 2).

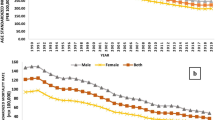

In the same year, the total number of TB mortality was 39,933 deaths (95% UI; 30,488-55,039), highest in people aged 15–49 years (13,916, 95% UI; 9311-20,530) but lowest in those aged between 5 and 14 years (875, 95% UI; 600-1,211) (Table 3). A similar pattern in the prevalence of TB mortality was observed (Fig. 2). Between 2000 and 2016, the age-standardised prevalence and incidence rates of TB-HIV negative decreased by 20.0 and 87.6%, respectively. The age-standardised mortality rate also dropped by 191.6% over the same period. Drug-susceptible TB was the most common variant, followed by multidrug- resistance TB in 2016 (Table 1).

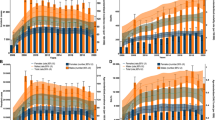

In Nigeria, the burden of TB among HIV-negative people was highest in those aged 15–49 years (660,942 DALYs [477,430-921,111]), followed by people aged 50–69 years (312,294, 95% UI; 227,215-440,406) (Table 4).

In 2016, YLLs were highest among people aged 15–49 years (623,955, 95% UI; 442,103-888,510), followed by those aged 50–69 years (301,086, 95% UI; 216,478-428,083) (Additional file 1: Table S1). YLDs were highest in those aged 15–49 years (36,987, 95% UI; 22,578-55,926) and adults between 50 and 69 years (11,208, 95% UI; 6263-17,761]) (Additional file 1: Table S2). Between 1990 and 2016, DALYs and YLLs decreased in all age group over time, while there were variations in the YLDs across the age groups.

TB mortality and DALYs attributable to individual risk factors

In Nigeria, alcohol use accounted for 13,196 (95% UI; 7277-20,605) TB deaths among HIV-negative people in 2016, followed by diabetes (1486 deaths [818–2493]) and smoking (942 deaths [349–1756]) (Additional file 1: Table S3). Proportionally, TB deaths that could be attributed to alcohol use was 38%, (95% UI; 23–52%), diabetes (4%, 95% UI; 3–6%) and smoking (3%, 95% UI; 1–5%) in 2016. The number of DALYs from TB due to alcohol use was 496,147 (95% UI; 283,342-777,331), followed by diabetes at 45,926 (95% UI; 26,297-75,452) and smoking at 32,369 (95% UI; 11,417-60,737) in 2016 (Additional file 1: Table S3).

Discussion

In Nigeria, the prevalence of TB among HIV-negative people was 27%, the TB incidence rate was 158 per 100,000 population, and the total number of TB mortality was 39,933 in 2016. From 2000 to 2016, the age-standardised prevalence, incidence and mortality rates dropped considerably, with variations across the age groups. The number DALYs due to TB among HIV-negative Nigerians varied across the age groups; highest in those aged 15–49 years, followed by people aged 50–69 years and children under 5 years in 2016. Alcohol use accounted for the highest number of deaths and DALYs that could be attributed to TB in 2016, followed by diabetes and smoking, probably reflecting the high burden of TB among older adults.

Consistent with previous studies [1, 32, 33], this study showed that the prevalence and incidence of TB among HIV-negative people were higher in adults compared to children in Nigeria. Evidence has shown that not all individuals who are exposed to the Mycobacterium tuberculosis progress to having active TB infections. Studies from high burden TB environments suggest that approximately 20% of people maintain negative tuberculin skin tests throughout their lifespan despite repeated exposure to the mycobacteria [34]. In young children, active TB disease usually results from the haematogenous spread of the mycobacterium after primary infection, associated with subsequent pulmonary and extrapulmonary infections in some cases. In adults, however, TB infection is usually pulmonary and may reflect the reactivation of the latent TB infection (LTBI) from a primary site, which may partly be responsible for the increased prevalence and incidence observed in adults [35]. While only a limited number of individuals with LTBI progress to active TB disease, it is worth noting that one untreated infected person can transmit the disease to many healthy people, with broader implications for population health and TB control programmes [36, 37]. Early treatment of advanced LTBI in high TB-endemic countries like Nigeria is been advocated [38], and if the intervention is well implemented, it would reduce TB incidence and improve survival and productivity.

The present study showed that the number of deaths from TB mortality had dropped substantially over time in Nigeria, consistent with other reports [1, 2]. Similarly, between 2000 and 2016, this study indicated that TB incidence has declined. This improvement could be attributed to the scale-up of strategic policies and interventions, socioeconomic growth and a stable political environment [33, 39, 40], as well as increased developmental assistance for health and impact of the Millennium Development Goal agenda [17]. However, the WHO Tuberculosis Report 2017 indicated that TB incident cases have remained stagnant in Nigeria since the year 2000 [1]. The variation in the findings may be due to the data sources and methodological approach used wherein the WHO estimated TB incidence based on WHO notification [1]. The GBD study, however, employed a statistical triangulation method that utilised all data sources (including data from the WHO global TB database and surveillance data) in Nigeria for TB estimation [3, 41]. A recent systemic review conducted in Nigeria reported higher levels of MDR-TB compared to the WHO estimate [42]. Despite the differences in data sources and methodology, both the WHO and GBD study reported similar estimates for global TB incidence and mortality in 2016 [1, 28].

Globally, delayed TB diagnosis and treatment has been shown to increase the transmission of the mycobacterium, exacerbate the disease, increase the likelihood of mortality [43,44,45] and may be a reason for why TB incident cases have not reduced considerably compared to TB mortality [1, 3]. Evidence from regional areas of Nigeria found that delayed diagnosis and treatment of TB was due to factors such as a lack of awareness of TB symptoms by primary health professionals, older age, distance to the public health facility, male gender, and first clinic visit to a non-tuberculosis control programme providers [43, 46,47,48]. Additional studies have suggested that a lack of knowledge about TB in the community and patients preference for private health practitioners are the major reasons for why patients delay TB treatment [44, 45]. However, Lambert and Van der Stuyft argued that the failed health care system should be blamed and not the patient because there is limited evidence to indicate that health education about TB could reduce treatment delays [49]. Improving timely diagnosis and treatment of TB in Nigeria will require improved human resources, better coordination and decentralisation of TB control programmes [6], as well as increased and monitoring of public health financing [50].

The estimation of the population attributable risk for a specific disease or injury is crucial for health and other relevant agencies to identify opportunities for preventive efforts and policy priorities [22, 51, 52]. In the current study, we found that alcohol use, tobacco smoking and diabetes were essential contributors to the burden of TB in Nigeria. Studies have shown that the association between alcohol use [53, 54], smoking [55] and tuberculosis is due to impairment of the host immune system (innate and adaptive response), which increases vulnerability to TB infection, or reactivation of latent TB infection. Diabetes leads to increased susceptibility to tuberculosis through direct effects of hyperglycaemia and inadequate secretion of insulin at the cellular level, as well as indirect effects on specialised anti-TB immune cells (macrophages and lymphocytes), where chemotaxis, phagocytosis, activation and antigen presentation by macrophages are impaired [7, 56].

Evidence from regional areas of Nigeria has suggested that the lifetime prevalence of alcohol use was 57.9% [57], while the overall prevalence of current alcohol use ranged from 15 to 24% [57,58,59,60]. In Nigeria, there are some policy initiatives (excise tax on beer, wine and spirits, the national legal minimum age for on/off-premise sales of alcoholic beverages and regulations on alcohol advertising) to limit alcohol use. However, there is currently no written national action plan, nor is there a national monitoring system or enforcement of relevant policies to reduce alcohol use [61]. For tobacco smoking, an estimated 5.6% Nigerian adults aged over 15 years smoked tobacco products in 2017 [62]. Similar to alcohol use initiatives, strategic policies to support Nigerians to quit smoking [62], as well as efforts to prevent diabetes, are weak [63, 64]. Our finding implies that efforts must not only be made to strengthen the health system and its human resources for TB control but also calls for collaborative, targeted and measurable socioeconomic reforms that address issues of alcohol use, tobacco, smoking and vulnerabilities, galvanised with strong political support to reduce TB burden in Nigeria.

The current study has policy implications for national health agencies and development partners aiming to reduce the high burden of TB and improve the quality of life in Nigeria because it provides relevant country-specific epidemiologic data for TB disease. The World Health Organization End TB Strategy highlights priority areas for attention to end the global TB epidemic, with targets to reduce TB deaths by 95% and to cut incidence by 90% between 2015 and 2035 [65, 66]. The WHO domains include integrated, patient-centred TB care and prevention; bold policies and supportive systems; and intensified research and innovation. For Nigeria to achieve the WHO goal of ending TB, a multipronged approach will be needed. Those strategic measures will include closing the funding gaps for TB control programmes and reducing the reliance on international donors; scaling up the national immunisation schedule (including the anti-TB vaccine, bacillus calmette–guérin) in underserved areas; improving the political commitment at all levels of government; and strengthening the healthcare system and TB diagnosis and surveillance [3, 42], including improving coordination, integration and consistency in the primary health care structure through the National Primary Care Health Development Agency [6]. Additional measures to reduce the high burden of TB in Nigeria should also include initiatives to limit alcohol use and prevent tobacco smoking and diabetes [3].

The study has several methodological limitations, and they have been described in detail elsewhere [3, 21, 22]. Briefly, caution should be exercised when interpreting the study findings especially that vital registration and other high-quality data for TB are sparse at the subnational and national levels in Nigeria. Importantly, the availability of high-quality TB data at the subnational level is essential given differences in the socioeconomic and political situation in Nigeria which have been shown to influence healthcare and social policies [67, 68]. In the present study, the assessment of TB mortality was based on various modelling strategies of WHO notification and other published data. Consequently, the TB estimates for Nigeria with limited high-quality data are reflected in the wide uncertainty intervals. Efforts at improving both subnational and national research, surveys and vital statistics on TB disease burden are warranted in Nigeria to guide strategic policy interventions. While there is biological plausibility for the association between malnutrition and TB, the attributable burden of malnutrition due to TB was not examined in GBD 2016 because of limited evidence of a casual association. The limitations related to the estimation of TB incidence, YLLs, YLDs and DALYs using the GBD Bayesian meta-regression tool also applied to this study [24, 25]. Publication bias relating to the use of the GBD data may also be a limitation. Despite these limitations, this study provides comprehensive country-level epidemiologic data on TB disease burden and attributable risk factors to inform better TB prevention and control programmes in Nigeria, a country with Africa’s largest population of over 186 million people [40]. Future studies which investigate the rate of decline of TB incidence and mortality at the subnational level and whether those declines are fast enough to meet the WHO End TB Strategy may be warranted.

Conclusion

Between 1990 and 2016, the present study showed a decreasing trend in TB disease burden among HIV-negative people in Nigeria. Despite this progress, TB disease remains a significant public health issue in the country. Efforts to ensure a further reduction in TB disease burden, as well as improve the health and well-being of Nigerians, will require a multipronged approach that includes increased funding and appropriate monitoring, health system strengthening and enhanced national and subnational surveillance for TB disease.

Abbreviations

- CRA:

-

Comparative risk assessment

- DALYs:

-

Disability-adjusted life years

- GBD:

-

Global burden of disease

- LTBI:

-

Latent tuberculosis infection

- MDR-TB:

-

Multidrug-resistant TB

- TB:

-

Tuberculosis

- UI:

-

Uncertainty intervals

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- YLDs:

-

Years lived with disability

- YLLs:

-

Years of life lost

References

World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2017. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. Licence: CC BY-NCSA 3.0 IGO

World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2016. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016.

GBD Tuberculosis Collaborators. The global burden of tuberculosis: results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;3099(17):30692–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30703-X.

World Health Organization. Use of high burden country lists for TB by WHO in the post-2015 era. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015. Contract No.: WHO/HTM/TB/2015.29

Owoseye A. Nigeria adopts shorter treatment for drug-resistant tuberculosis. Online: Premuim Times 2017 [cited 2018 11 January ]. Available from: https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/more-news/235781-nigeria-adopts-shorter-treatment-drug-resistant-tuberculosis.html.

Federal Ministry of Health - Nigeria. The National Strategic Plan for Tuberculosis Control - Towards Universal Access to Prevention, Diagnosis and Treatment 2015–2020. Abuja: Federal Ministry of Health; 2015.

Dooley KE, Chaisson RE. Tuberculosis and diabetes mellitus: convergence of two epidemics. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9(12):737–46.

Patra J, Jha P, Rehm J, Suraweera W. Tobacco smoking, alcohol drinking, diabetes, low body mass index and the risk of self-reported symptoms of active tuberculosis: individual participant data (IPD) meta-analyses of 72,684 individuals in 14 high tuberculosis burden countries. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e96433.

Rehm J, Samokhvalov AV, Neuman MG, Room R, Parry C, Lönnroth K, et al. The association between alcohol use, alcohol use disorders and tuberculosis (TB). A systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2009;9(1):450.

Nelson S, Zhang P, Bagby GJ, Happel KI, Raasch CE. Alcohol abuse, immunosuppression, and pulmonary infection. Curr Drug Abus Rev. 2008;1(1):56–67.

Volkmann T, Moonan P, Miramontes R, Oeltmann J. Tuberculosis and excess alcohol use in the United States, 1997–2012. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2015;19(1):111–9.

Leung CC, Yew WW, Chan CK, Chang KC, Law WS, Lee SN, et al. Smoking adversely affects treatment response, outcome and relapse in tuberculosis. Eur Respir J. 2015;45(3):738–45.

Akinyemiju T, Abera S, Ahmed M, Alam N, Alemayohu MA, Allen C, et al. The burden of primary liver cancer and underlying etiologies from 1990 to 2015 at the global, regional, and national level: results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(12):1683–91.

Melaku YA, Appleton SL, Gill TK, Ogbo FA, Buckley E, Shi Z, et al. Incidence, prevalence, mortality, disability-adjusted life years and risk factors of cancer in Australia and comparison with OECD countries, 1990–2015: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Cancer Epidemiol. 2018;52:43–54.

Charara R, Bcheraoui EC, Mokdad HA, Khalil I, Moradi-Lakeh M, Afshin A, et al. The burden of mental disorders in the Eastern Mediterranean region, 1990–2015: findings from the global burden of disease 2015 study. Int J Public Health. 2017:1–13.

Fitzmaurice C, Allen C, Barber RM, Barregard L, Bhutta ZA, Brenner H, Fleming T. Global, regional, and national cancer incidence, mortality, years of life lost, years lived with disability, and disability-adjusted life-years for 32 cancer groups, 1990 to 2015: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study. JAMA oncology. 2017;3(4):524–548.

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). Financing Global Health 2016: development assistance, public and private health spending for the pursuit of universal health coverage. Seattle: IHME; 2017.

Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Alternative projections of mortality and disability by cause 1990–2020: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 1997;349(9064):1498–504.

Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Measuring global health: motivation and evolution of the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 2017;390(10100):1460–4.

Stevens GA, Alkema L, Black RE, Boerma JT, Collins GS, Ezzati M, et al. Guidelines for accurate and transparent health estimates reporting: the GATHER statement. PLoS Med. 2016;13(6):e1002056.

Naghavi M, Abajobir AA, Abbafati C, Abbas KM, Abd-Allah F, Abera SF, et al. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific mortality for 264 causes of death, 1980–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390(10100):1151–210.

Gakidou E, Afshin A, Abajobir AA, Abate K, Hassen AC, Abbas MK, et al. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 84 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390:1345–422.

Haidong W, Amanuel AA, Kalkidan HA, Cristiana A, Kaja MA, Foad A-A, et al. Global, regional, and national under-5 mortality, adult mortality, age-specific mortality, and life expectancy, 1970–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390:1084–150.

Hay IS, Abajobir AA, Abate KH, Abbafati C, Abbas KM, Abd-Allah F, et al. Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for 333 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390(10100):1260–344.

Vos T, Abajobir AA, Abbafati C, Abbas MK, Abate KH, Abd-Allah F, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390:1211–59.

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). Global Burden of Disease Study 2016 (GBD 2016) Data Input Sources Tool Online: IHME; 2018 [cited 2018 29 March]. Available from: http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-2016/data-input-sources.

World Health Organization. The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992.

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. GBD Compare Online2018 [cited 2018 14 January ]. Available from: https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare/.

Wang H, Naghavi M, Allen C, Barber RM, Bhutta ZA, Carter A, et al. Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388(10053):1459–544.

Murray CJ, Barber RM, Foreman KJ, Ozgoren AA, Abd-Allah F, Abera SF, et al. Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 306 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 188 countries, 1990–2013: quantifying the epidemiological transition. Lancet. 2015;386(10009):2145–91.

Murray CJ, Lopez AD. On the comparable quantification of health risks: lessons from the Global Burden of Disease Study. Epidemiology-Baltimore. 1999;10(5):594–605.

Dim CC, Dim NR. Trends of tuberculosis prevalence and treatment outcome in an under-resourced setting: the case of Enugu state, South East Nigeria. Niger Med J. 2013;54(6):392.

Federal Ministry of Health - Nigeria. Report first national TB prevalence survey 2012, Nigeria. Abuja: Federal Ministry of Health; 2012.

Kassim S, Zuber P, Wiktor S, Diomande F, Coulibaly I, Coulibaly D, et al. Tuberculin skin testing to assess the occupational risk of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection among health care workers in Abidjan, Cote d’Ivoire. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2000;4(4):321–6.

Alcaïs A, Fieschi C, Abel L, Casanova J-L. Tuberculosis in children and adults: two distinct genetic diseases. J Exp Med. 2005;202(12):1617–21.

Flynn JL, Chan J. Tuberculosis: latency and reactivation. Infect Immun. 2001;69(7):4195–201.

Getahun H, Matteelli A, Chaisson RE, Raviglione M. Latent mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(22):2127–35.

World Health Organization. Guidelines on the management of latent tuberculosis infection. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015.

Kana MA, Doctor HV, Peleteiro B, Lunet N, Barros H. Maternal and child health interventions in Nigeria: a systematic review of published studies from 1990 to 2014. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):334.

The World Bank. Nigeria: The World Bank; 2017 [cited 2018 22 January ]. Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/country/nigeria.

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Global Burden of Disease Study 2016 (GBD 2016) Data Input Sources Tool Online2018 [cited 2017 14 December ]. Available from: http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-2016/data-input-sources.

Onyedum CC, Alobu I, Ukwaja KN. Prevalence of drug-resistant tuberculosis in Nigeria: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12(7):e0180996.

Sullivan BJ, Esmaili BE, Cunningham CK. Barriers to initiating tuberculosis treatment in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review focused on children and youth. Glob Health Action. 2017;10(1):1290317.

Sreeramareddy CT, Qin ZZ, Satyanarayana S, Subbaraman R, Pai M. Delays in diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis in India: a systematic review. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2014;18(3):255–66.

Takarinda KC, Harries AD, Nyathi B, Ngwenya M, Mutasa-Apollo T, Sandy C. Tuberculosis treatment delays and associated factors within the Zimbabwe national tuberculosis programme. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):29.

Ukwaja KN, Alobu I, Nweke CO, Onyenwe EC. Healthcare-seeking behavior, treatment delays and its determinants among pulmonary tuberculosis patients in rural Nigeria: a cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13(1):25.

Odusanya OO, Babafemi JO. Patterns of delays amongst pulmonary tuberculosis patients in Lagos, Nigeria. BMC Public Health. 2004;4(1):18.

Babatunde OI, Bismark EC, Amaechi NE, Gabriel EI, Olanike A-UR. Determinants of treatment delays among pulmonary tuberculosis patients in Enugu Metropolis, South-East, Nigeria. Health. 2015;7(11).

Lambert M, Van Der Stuyft P. Delays to tuberculosis treatment: shall we continue to blame the victim? Tropical Med Int Health. 2005;10(10):945–6.

Ogbo FA, Page A, Idoko J, Claudio F, Agho KE. Have policy responses in Nigeria resulted in improvements in infant and young child feeding practices in Nigeria? Int Breastfeed J. 2017;12:9.

Forouzanfar MH, Afshin A, Alexander LT, Aasvang GM, Bjertness E, Htet AS, et al. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388:1659–724.

Ogbo FA, Page A, Idoko J, Agho KE. Population attributable risk of key modifiable risk factors associated with non-exclusive breastfeeding in Nigeria. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:247. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5145-y.

Lönnroth K, Williams BG, Stadlin S, Jaramillo E, Dye C. Alcohol use as a risk factor for tuberculosis—a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2008;8(1):289.

Imtiaz S, Shield KD, Roerecke M, Samokhvalov AV, Lönnroth K, Rehm J. Alcohol consumption as a risk factor for tuberculosis: meta-analyses and burden of disease. Eur Respir J. 2017;50(1):1700216.

Feldman C, Anderson R. Cigarette smoking and mechanisms of susceptibility to infections of the respiratory tract and other organ systems. J Infect. 2013;67(3):169–84.

Moutschen M, Scheen A, Lefebvre P. Impaired immune responses in diabetes mellitus: analysis of the factors and mechanisms involved. Relevance to the increased susceptibility of diabetic patients to specific infections. Diabete Metab. 1992;18(3):187–201.

Lasebikan VO, Ola BA. Prevalence and correlates of alcohol use among a sample of Nigerian semirural community dwellers in Nigeria. J Addict. 2016;2016. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/2831594.

Okonoda KM, Mwoltu G, Yakubu K, James B. Alcohol use disorders among participants of a community outreach in Jos, Nigeria: prevalence, correlates and ease of acceptance of brief intervention. J Med Sci Clin Res. 2017;5(5):22049–56.

Awosusi A, Adegboyega J. Alcohol consumption and tobacco use among secondary school students in Ekiti State, Nigeria. Int J Educ Res. 2015;3(5):11–20.

Adelekan M, Ndom R, Makanjuola A, Parakoyi D, Osagbemi G, Fagbemi O, et al. Trend analysis of substance use among undergraduates of university of Ilorin, Nigeria, 1988–1998. African J Drug Alcohol Studies. 2000;1(1):39–52.

World Health Organization. Global status report on alcohol and health, 2014. World Health Organization Management of Substance Abuse Unit, editor. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014.

World Health Organization. WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2017; Country profile: Nigeria. Geneva: World Health Organzation.

Fasanmade OA, Dagogo-Jack S. Diabetes care in Nigeria. Ann Glob Health. 2015;81(6):821–9.

Adeloye D, Ige JO, Aderemi AV, Adeleye N, Amoo EO, Auta A, et al. Estimating the prevalence, hospitalisation and mortality from type 2 diabetes mellitus in Nigeria: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2017;7(5):e015424.

Uplekar M, Weil D, Lonnroth K, Jaramillo E, Lienhardt C, Dias HM, et al. WHO’s new End TB Strategy. Lancet. 2015;385(9979):1799–801.

World Health Organization. The End TB Strategy. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2015. Contract No.: WHO/HTM/TB/2015.19

Ogbo FA, Agho KE, Page A. Determinants of suboptimal breastfeeding practices in Nigeria: evidence from the 2008 demographic and health survey. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:259.

The Federal Government of Nigeria. The millenium development goals performance tracking survey 2015 report. Abuja, Nigeria: National Bureau of Statistics; 2015.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation for providing the data.

Funding

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Availability of data and materials

The present study was based on the publicly available data sets from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation website. All data used in this report are freely available at the Global Health Data Exchange database (http://ghdx.healthdata.org/).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FAO conceptualised the study, contributed to the data preparation and interpreted the results, drafted the original manuscript and critically revised the manuscript. PO prepared the data, interpreted results and critically revised the manuscript. AO, BOO, JO, IKI, AOA, JE and AP provided advice on data preparation and interpretation and critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The present study was based on published data from the GBD 2016 study, which does not require specific institutional ethics approval.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Table S1. Number of years of life lost (with 95% uncertainty interval, UI) due to tuberculosis in Nigeria, 1990–2016. Table S2. Number of years of life lived with disability (with 95% uncertainty interval, UI) due to tuberculosis in Nigeria, 1990–2016. Table S3. Numbers of deaths and disability-adjusted life years (with 95% uncertainty interval, UI) from tuberculosis due to attributable risk factors in Nigeria, 1990–2016. (DOCX 25 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Ogbo, F.A., Ogeleka, P., Okoro, A. et al. Tuberculosis disease burden and attributable risk factors in Nigeria, 1990–2016. Trop Med Health 46, 34 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41182-018-0114-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41182-018-0114-9