Abstract

Background

In a previous experimental study, new bone was found growing within granules of HA/β-TCP. In vitro and experimental studies have shown increased protein adsorption and cell adhesion graft material bioactivated with Argon plasma. The aims of the present experiment were to study new bone ingrowth into β-TCP/HA granules used as filler material for sinus lifting and the influence on the healing of the bioactivation of the graft with argon plasma.

Methods

Sinus lifting was carried out in 20 rabbits using 60% HA and 40% β-TCP as filler material either bio-activated with argon plasma (plasma group) or left untreated (control group). The antrostomies were closed with collagen membranes. Biopsies representing the healing after 2 and 10 weeks were collected, and ground sections were prepared for histomorphometric analyses. Various regions of the elevated space were analyzed both around (outer bone; OB) and inside (interpenetrating bone network, IBN) the graft particles.

Results

After 2 weeks of healing, 8.2% and 9.3% (n = 10; p = 0.635) of total new bone (OB + IBN) was found in the plasma and control groups, respectively. Small fractions of IBN were found, spreading from the periphery inward of the graft particles. After 10 weeks of healing, the total new bone was 34.0% in the plasma and 31.3% in Control groups (n = 9; p = 0.594). The respective fractions of IBN were 18.0% and 16.0%. New bone was penetrating from the peripheral regions inside the remnants of graft particles, where it was forming a network of bridges in continuity to the remnants of biomaterial through its porosities. The biomaterial decreased in proportion between 2 and 10 weeks from 52.1 to 28.3% in the plasma group, and from 52.5% to 31.9% in the control group.

Conclusion

The bio-activation with argon plasma on a synthetic graft composed of 60% HA and 40% β-TCP used as filler material for sinus lifting showed a tendency to improve bone formation; however, the difference with the control group was neither statistically significant nor clinically relevant.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The use of biomaterials to maintain the volume obtained after sinus floor elevation is a procedure well documented in scientific literature [1,2,3]. Depending on the degrees of resorption of the graft used, different proportions of bone might be found inside the elevated space. In a systematic review with meta-analysis [4], it was shown that the autologous bone alone produced the highest amount of new bone when compared to xenografts or synthetical biomaterials.

A literature review [5] showed the intrinsic healing pattern of this anatomical structure, underlining the importance of the bone walls of the sinus cavity, which were recognized to be the most important source of blood supply and regenerative potential.

The histologically pattern of this clinical phenomenon was clarified in several animal studies [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14] These studies in fact confirmed that the regeneration process starts from the bony walls and increases if the lateral bony wall is maintained attached to the mucosa [15, 16]..

Although the importance of the graft material to fill the sinus cavity was questioned by a recent systematic review [17] highlighting the possibility to longitudinally maintain implants in a sinus lifted without graft, however a significant difference in terms of survival rate was found when compared to grafted sinus.

Although the best material was documented to be the autologous bone, due to its osteo-inductive properties, it was documented that the use of a graft material, mostly in case of critical anatomical conditions, could speed and enhance the quality of hard tissue regeneration under the sinus mucosa [18].

All the graft materials, however, share the same biologic path to be osseointegrated: the key factor is represented by their wettability once exposed to the blood proteins. In fact, linking proteins (extracellular matrix molecules) are essential for the initiation and modulation of cell adhesion with regenerative potential [19]. Then, the material properties, moreover the wettability of the graft granules, may represent a key factor in bone regeneration.

One technique recently appeared on the literature to increase the graft surface hydrophilicity, is plasma of Argon which through the alteration of the electronic mantel of the surface, positively alter the surface charge of the material [20]. In fact, the treatment with argon plasma has been tested in an in vitro study in which four types of discs made of synthetic pure hydroxyapatite, biphasic calcium phosphate (60% HA, 40% β-TCP), cancellous and cortical xenogeneic bone matrix were used [21]. It was shown that the bioactivation increased significantly protein adsorption and cell adhesion. Plasma treatment has been shown to increase also the osteoconductivity on biomaterials [22] and osseointegration on implants [23].

Moreover, a recent publication showed that bovine bone matrix in the rabbit sinus lift clearly identified a significantly better regeneration pattern in the central area of the sinus in case of bioactivated graft, the most distant area from osteogenesis sources [24].

It was furthermore described in an experimental study in sheep the pattern of healing of 40% β-TCP/60% HA granules used for sinus lifting. Large amounts of new bone were found growing inward the synthetic biomaterial, interpenetrating the resorbing graft granules [25].

Hence, the aims of the present experiment were to study new bone ingrowth into β-TCP/HA granules used as filler material for sinus lifting and the influence on the healing of the bioactivation of the graft with argon plasma. The hypothesis was that the treatment with argon plasma might enhance bone formation both around and within of the HA and β-TCP granules.

Materials and methods

Ethical statement

The ethical approval of the protocol for the present study was given by the Ethical Committee at the School of Dentistry, of Ribeirão Preto, University of Sao Paulo (USP), with the code 2018.1.454.58.2 signed on 19 September 2018. The ARRIVE checklist for animal studies was followed. The international and local guidelines for animal experiments were respected.

Study design

Sinus floor augmentation was performed bilaterally in 20 rabbits. The elevated spaces were grafted with a synthetic biomaterial either activated (plasma group) or not activated (control group) with argon plasma. Ten rabbits were euthanized after 2 weeks and 10 rabbits after 10 weeks.

Bioactivation with argon plasma

The alloplastic granules were moved from the vials to a sterile cup using a small spoon and then placed in an argon plasma reactor (10 W, 1 bar for 12 min, plasma R, Diener, Germany) for the activation procedure.

Experimental procedures

The sedation was performed using acepromazine 1.0 mg/kg (Acepran®, Vetnil, Louveira, São Paulo, Brazil) injected subcutaneously, followed by the anesthesia that was carried out with xylazine 3.0 mg/kg (Dopaser®, Hertape Calier, Juatuba, Minas Gerais, Brazil) and ketamine hydrochloride 50 mg/kg (Ketamin Agener, União Química Farmacêutica Nacional S/A, Embu-Guaçú, São Paulo, Brazil) IM. Local anesthesia was also carried out with mepivacaine 2% and epinephrine 1:100.000 (Mepiadre, Nova DFL, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil).

In all rabbits, a masked maxillofacial surgeon (ERS; see the “Acknowledgements” section) performed a dermo-periosteal incision, exposed the nasal bone, and prepared rounded antrostomies with a trephine 3.5 mm in diameter, both sides of the nasal-incisal suture (Fig. 1a). The bone window was removed and the sinus mucosa was elevated and then grafted with similar amounts of biomaterial (~ 130 ml), composed of 60% hydroxyapatite and 40% beta-tricalcium phosphate irregular-shaped granules (GUIDOR calc-i-oss CRYSTAL+; Sunstar, Etoy, Switzerland), with dimension of 450–1000 micrometers (Fig. 1b). The granules contained macropores and only those used for the test sites (plasma group) were bioactivated in the argon plasma reactor. Both for the plasma and control groups, the granules were maintained dried until the placement in the elevated space. Collagen membranes (Bio-Gide; Geistlich Biomaterials, Wolhusen, LU, Switzerland) were used to cover both antrostomies (Fig. 1c).

Clinical view of the surgical procedures. a Rounded antrostomies were prepared with a trephine 3.5 mm in diameter, both sides of the nasal-incisal suture. b After the elevation of the sinus mucosa, dried 60% hydroxyapatite and 40% beta-tricalcium phosphate granules were grafted into the elevated space (plasma site on the left)

Euthanasia

After sedation, the animals were euthanized with sodium thiopental (1.0 g, 2 mL, Thiopentax®, Cristália Produtos Químicos Farmacêuticos, Itapira, São Paulo, Brazil).

Experimental animals

Twenty New Zealand male rabbits of about 5–6 months of age and 3–3.5 kg of weight used for the experiment.

Housing and husbandry

The animals were maintained individually in cages located in rooms under a controlled environment at the facilities of the School of Dentistry, USP, Ribeirão Preto (Brazil). Pain, biological functions and wounds were daily monitored. No restrictions were applied for food and water.

The animals received a prophylactic dose of oxytetracycline dehydrate (40 mg/kg, IM, Terramicina LA, Zoetis Indústria e Produtos Veterinários, Campinas, Sao Paulo, Brazil). Postoperatively, the animals received ketoprofen (3.0 mg/kg, IM., Ketofen 1%, Merial, Monte-Mor, Sao Paulo, Brazil) and tramadol hydrochloride (Tramadol 2%, 1.0 mg/kg, SC., Cronidor, Agener União Saúde Animal, Apucarana, Parana, Brazil) for 2 days.

Sample size

No data were available on similar treatment in vivo on alloplastic graft with argon plasma so that a difference of 10% of new bone within the elevated space was judged as clinically relevant. Applying a standard deviation of 10%, a power of 0.8 and an α = 0.05, a sample of 10 animals each group was calculated to disclose differences clinically relevant. This allowed maintaining the number of animals as low as possible, as required by the 3R rules [26].

Randomization and allocation concealment

The randomization was made by a researcher that did not participate to the surgery (DB) at the website www.randomization.com. The allocation treatments were secured in sealed opaque envelopes that were opened after the elevation of both sinuses by an author (SPX) not involved in the surgical procedures.

Histological preparation and analyses

The histological procedures were already described in a previous article [10]. Briefly, the sections, each containing both sinuses, were prepared in blocks, fixed in 10% buffered formalin, dehydrated in ascending concentrations of alcohol, and then embedded in resin. Two ground sections were prepared for each biopsy using the Exakt equipment (Exakt®, Apparatebau, Norderstedt, Germany). The histological slides were stained with either Stevenel’s blue and alizarin red or toluidine blue. Digital photomicrographs of all ground sections were taken at a magnification × 100 using an EK14 motorized stage (Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) connected to an Eclipse Ci microscope (Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

Morphometric evaluations were performed in the histological slides stained with Stevenel’s blue and alizarin red. The software NIS-Elements D 5.11 (Laboratory Imaging, Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) was used for measurements. For this purpose, a lattice with squares of 75 μm in dimensions was superposed to the images. Various regions of the sinus were evaluated: (i) close to the bone walls (Bone walls region), (ii) the most central area of the elevated space (Central region), (iii) the region subjacent the sinus mucosa (Sub-mucosa region), (iv) and a region close to the antrostomy (close-to-window region). The following tissues were assessed: outer bone (OB; new bone outside the biomaterial residues), interpenetrating bone network (IBN; new bone consolidated within the biomaterial residues), residual alloplastic graft, soft tissues, vessels, osteoclastic zones, and inflammatory infiltrate.

Calibration for histometric evaluations

An expert examiner, not included in the list of authors, did all histological assessments (KAAA see the “Acknowledgements” section), after having performed a calibration with another expert (DB) that resulted in a K > 0.90 inter-rater agreement.

Experimental outcomes

The primary variables were the percentage of the interpenetrating bone network (IBN) and the percentage of total bone within the elevated space that was calculated as the sum of the outer bone (OB) and the interpenetrating bone network (IBN). The other variables, namely, outer bone, residual alloplastic graft, soft tissues, vessels, osteoclastic zones, and inflammatory infiltrate were considered as secondary variable.

Statistical methods

Differences between plasma (test) and the control groups were analyzed with a Wilcoxon test using the software IBM SPSS Statistics (IBM Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). An α = 5% was applied.

Results

None of the animals presented complications at the surgery and during the maintenance period. However, one histological specimen belonging to the 10 weeks group was lost for technical problems so that n = 10 and an n = 9 were achieved for the 2-week and 10-week groups, respectively.

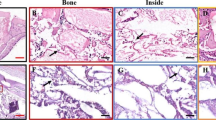

After 2 weeks of healing (Fig. 2a–d), in both groups, new bone was found surrounding the graft particles in the periphery (outer bone, OB) and spreading inward the graft particles in small quantities (interpenetrating bone network, IBN). Soft tissues, cells and vessels were visible both around and within the graft. Osteoclasts were found in the periphery of the biomaterial. The total new bone was 8.2 ± 7.0% and 9.3 ± 8.5% at the plasma and control group, respectively (p = 0.635; Table 1). Most of the new bone was located outside (OB) the residues of the granules of biomaterial. However, few fractions of 2.2 ± 2.4% and 3.3±4.3% (p=0.093) of new bone was found inside the residues of the granules (IBN). Biomaterial devoid of new bone was found in proportion of 52.1 ± 12.4% in the plasma group, and 52.5 ± 8.1% in the control group (p = 0.575).

Graft particles showing various grades of resorption after 2 weeks of healing. New bone was found surrounding the graft particles in the periphery (outer bone; OB) and spreading inward the graft particles in small quantities (interpenetrating bone network; IBN). Soft tissues, cells and vessels are visible within the graft. Osteoclastic zones were found in the periphery of the graft (red arrows in a and b indicate some examples). a, b Plasma group. c, d Control group. a–c Bone wall regions. b–d Sub-mucosa regions. The asterisks indicate examples of OB (yellow) and IBN (green). Stevenel’s blue and alizarin red stain

Within the various regions examined, the highest amount of new bone was found in the Bone walls region while the lowest amount was in the central region (Table 2). Most commonly, higher amounts of OB were found compared to IBN. The highest fractions of IBN (~ 5%) were found in the Bone walls regions of both groups and in the Sub-mucosa region of the control group. No differences were found between groups for any of the variables evaluated.

After 10 weeks of healing, in both groups, higher amounts of newly formed bone were observed compared to the previous period analyzed. Biomaterial was still present, but in lower percentages compared the 2-week period. New bone was penetrating from the peripheral regions inside the remnants of graft particles forming a network of bridges interconnecting the outer bone with the biomaterial through its porosities (Fig. 3 a-d). Within the elevated space, new bone increased to 34.0 ± 17.3% in the plasma group and to 31.3 ± 11.9% in the control group (p = 0.594; Table 1). In this stage on healing, slightly higher amounts of IBN within the granule residues were found compared to the OB formed outside of these residues. No statistically significant differences were found between groups for both the OB (p = 0.767) and IBN (p = 0.407).

Healing after 10 weeks. Higher amounts of newly formed bone were observed in this period of healing compared the previous period analyzed, in both the plasma group (a, b) and the control group (c, d). New bone was penetrating from the peripheral regions (outer bone; OB) inside the remnants of graft particles forming a network of bridges interconnecting the peripheral bone with the biomaterial through its porosities (Interpenetrating bone network; IBN). a Central region. b–d Sub-mucosa regions. c Next to the bone wall region. The asterisks indicate examples of OB (yellow) and IBN (green). Stevenel’s blue and alizarin red

Within the various regions examined, the highest amount of new bone was found again in the bone walls region, reaching proportions of 47.1 ± 12.4% and 41.9 ± 12.5% in the plasma and control group, respectively (p = 0.214; Table 3). The new bone increased in all regions examined and higher amounts of IBN were found compared to OB in all regions with the exclusion of the Bone walls region.

Discussion

The aims of the present experiment were to study new bone ingrowth into β-TCP/HA granules used as filler material for sinus lifting and the influence on the healing of the bioactivation of the graft with argon plasma.

Small fractions of interpenetrating bone network (IBN) were already present after 2 weeks of healing. After 10 weeks, IBN reached similar percentages of the outer bone (OB).

After 2 weeks of healing, similar amounts of new bone were found in the plasma (8.2%) and in the control sites (9.3%). After 10 weeks of healing, bone increased considerably in both groups, with a tendency of higher bone formation in the plasma (34.0 ± 17.3%) compared to the control group (31.3 ± 11.9%). However, no statistically significant differences were found both after two (p = 0.635) and 10 (p = 0.594) weeks of healing.

The results from the present study are in agreement with those from another similar study in which DBBM granules were used [24]. In that study, similarly to the present study, the granules of the biomaterial planned to be grafted into the sinus of the test sites were activated with argon plasma. After 2 weeks of healing, similar fractions of woven bone were detected in both test (5.2%) and control (5.0%) sites. In the present study, after 2 weeks of healing, slightly higher values of new bone were found compared to that of the study mentioned above. These higher values might be related to that fact that bone was also formed inside the remnants of biomaterial (interpenetrating bone network) so that the total amount of new bone was expressed as the sum of the IBN and the outer bone (OB) formed outside the remaining graft.

In the study mentioned above [24], only the bone outside the granules of DBBM was assessed. The bone that possibly grew within the DBBM was not visible at the histological examination maybe because of its reduced quantity due to the high density, the low rate of resorption, and the low size of the porosities of that biomaterial [9, 27, 28]. In the present study, slightly over-lighting the histological slides at the light microscope, the new bone turned out to be visible through the graft under resorption. This allowed an evaluation also of this bone (IBN) that was penetrating inside the graft, forming a network of bridges interconnecting the outer bone with the remnants of the porous biomaterial. This aspect had been already described in a previous experimental study on sinus lifting in sheep [25]. After sinus mucosa elevation, the elevated space was filled with a similar graft used in the present study, also composed of 60% HA and 40% β-TCP. At the test sites, the bone window was repositioned on the antrostomy while, at the control site, the antrostomy was protected with a citric acid ester membrane. The graft was found interpenetrated by new bone for 37.1% and 33.1% at the test and control sties, respectively. The outer bone outside the graft was 16.4% and 15.0%, respectively.

After 10 weeks of healing, in a study mentioned above [24], 23.5% and 21.3% of new bone was found at the plasma and control groups, respectively. These proportions were higher compared to those of the OB assessed outside the graft granules in the present study that were 16.0% and 15.3% in the plasma and control group, respectively. However, in the present study, the IBN contributed to increase the total amount of new bone to 34.0% in the plasma group and 31.3% in the control group.

It should be considered that the biomaterial used in the present experiment exhibited macroporosity and a higher degradation compared to the rate of resorption reported for the DBBM. The intrinsic characteristics of the synthetic biomaterial used in the present study allowed the new bone to invade part of the graft while it was resorbing. In the DBBM study, instead, the new bone was laying on the surface of the graft. A larger portion of the elevated space was still occupied by this biomaterial after 10 weeks of healing compared to that found in the present study. In fact, even though, after 2 weeks of healing, the proportion of biomaterial was higher in the present experiment by 3–4% compared to the DBBM study [24]; after 10 weeks, the percentages of HA/β-CTP turned out to be lower compared to the DBBM percentage. This, in turn, means that the DBBM granules were still occupying larger part of the elevated space of the sinus, allowing the bone to grow on their surface and within the zones interposed among granules. Instead, the higher rate of graft degradation of the HA/β-TCP in conjunction with the growth of bone inside the macroporosities of the graft provided a further environment into which the bone could grow. This might explain the higher amount of new bone found in the present experiment compared to that reported in the DBBM study.

Bone formation in sinuses lifted using DBBM has been described in several studies [9, 14, 29, 30]. It was reported that new bone is mainly formed from the sinus bone walls and then propagates within the elevated space, towards the other regions. The DBBM granules are initially surrounded by a dense tissue rich in mesenchymal cells that, over time, is substituted by new bone contributing to the consolidation of the graft into the newly formed bone [9].

Similar experiments in rabbits used a collagenated cortico-cancellous porcine bone that presented a different pattern of healing compared to the present study [10,11,12,13, 31]. In one of these experiments [12], the bony window was repositioned on the antrostomy at the test site while, at control site, a collagen membrane was applied. After 2 weeks of healing, ~ 2% of new bone and 40% of xenograft were found in both sites. About 3% of resorption zones containing multinucleated cells were identified while, in the present study, only 0.1–0.2% of these cells was found. After 8 weeks of healing, new bone reached proportions of ~ 23–24% and the xenograft was reduced to ~ 11%. About 2% of resorptive zones with multicellular units were still observed. The collagenated cortico-cancellous porcine bone was either resorbed before allowing bone formation or, similarly to the DBBM, it was enclosed into new bone formed on its surface. No bone within the graft remnants was identified.

In the present study, after 10 weeks of healing, only 2.7% higher amount of total new bone was found at the plasma compared to the control group. The highest difference (9.4%; p = 0.208) in favor of the plasma group was registered in the central region of the elevated space. This result agrees with that reported in a study mentioned above in which DBBM was used [24]. In that study, after 10 weeks of healing, a statistically significant difference was found in favor of the plasma group only for the central region. It might be speculated that, own to the low rate of resorption of the DBBM, a high content of bioactivated biomaterial was still present in this period of healing, yielding a higher bone formation in the plasma sites compared to the untreated control sites. It was concluded that the bio-activation of the DBBM increased bone formation in regions far from the osteogenic sources.

In the present study, the highest percentages of new bone were found in the bone walls region. This agrees with the outcomes reported by several experimental studies on sinus lifting [9,10,11,12,13,14], that showed that the most important source for bone formation is represented by the pre-exiting sinus bony walls. Instead, the role of the sinus membrane in the early phases of healing is still under debate [7,8,9,10, 32,33,34,35,36,37].

In conclusion, the bio-activation with argon plasma on a synthetic graft composed of HA and β-TCP used as filler material for sinus lifting showed a tendency to improve bone formation. This tendency was higher in the central region, far from the osteogenic sources. However, the difference between test and control sites was neither statistically significant nor clinically relevant. The properties of the synthetic biomaterial allowed new bone ingrowth into the graft, forming a network of bridges interconnecting the bone formed outside the granules with the remnants of the porous biomaterial.

A limitation of the present study was the limited sample and the loss of the specimen of one animal. The animal model used is another limitation due to its accelerate rate of healing compared to that in human [38]. Comparisons with biomaterial with a lower rate of resorption should be performed to disclose differences. Biopsies in humans should be performed to confirm the histological data, using similar synthetic biomaterial, and studying new bone formation around and inside the graft.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Shanbhag S, Shanbhag V, Stavropoulos A. Volume changes of maxillary sinus augmentations over time: a systematic review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2014;29(4):881-892. doi: https://doi.org/10.11607/jomi.3472. Review.

Ting M, Rice JG, Braid SM, Lee CYS, Suzuki JB. Maxillary sinus augmentation for dental implant rehabilitation of the edentulous ridge: a comprehensive overview of systematic reviews. Implant Dent. 2017;26(3):438–64. https://doi.org/10.1097/ID.0000000000000606.

Coopman R, Fennis J, Ghaeminia H, Van de Vyvere G, Politis C, Hoppenreijs TJM. Volumetric osseous changes in the completely edentulous maxilla after sinus grafting and lateral bone augmentation: a systematic review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2020. pii: S0901-5027(20)30089-8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijom.2020.03.001.

Corbella S, Taschieri S, Weinstein R, Del Fabbro M. Histomorphometric outcomes after lateral sinus floor elevation procedure: a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2016;27(9):1106–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/clr.12702.

Stacchi C, Spinato S, Lombardi T, Bernardello F, Bertoldi C, Zaffe D, Nevins M. Minimally invasive management of implant-supported rehabilitation in the posterior maxilla, part i. sinus floor elevation: biologic principles and materials. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2020;40(3):e85–93. https://doi.org/10.11607/prd.4497.

Busenlechner D, Huber CD, Vasak C, Dobsak A, Gruber R, Watzek G. Sinus augmentation analysis revised: the gradient of graft consolidation. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2009;20(10):1078–83. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0501.2009.01733.x Epub 2009 Jun 10.

Scala A, Botticelli D, Rangel IG Jr, de Oliveira JA, Okamoto R, Lang NP. Early healing after elevation of the maxillary sinus floor applying a lateral access: a histological study in monkeys. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2010;21(12):1320–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0501.2010.01964.x.

Scala A, Botticelli D, Faeda RS, Garcia Rangel I Jr, Américo de Oliveira J, Lang NP. Lack of influence of the Schneiderian membrane in forming new bone apical to implants simultaneously installed with sinus floor elevation: an experimental study in monkeys. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2012;23(2):175–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0501.2011.02227.x.

Caneva M, Lang NP, Garcia Rangel IJ, Ferreira S, Caneva M, De Santis E, Botticelli D. Sinus mucosa elevation using Bio-Oss(®) or Gingistat(®) collagen sponge: an experimental study in rabbits. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2017;28(7):e21–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/clr.12850.

Iida T. Carneiro Martins Neto E, Botticelli D, Apaza Alccayhuaman KA, Lang NP, Xavier SP. Influence of a collagen membrane positioned subjacent the sinus mucosa following the elevation of the maxillary sinus. A histomorphometric study in rabbits. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2017;28(12):1567–76.

Iida T, Silva ER, Lang NP, Apaza Alccayhuaman KA, Botticelli D, Xavier SP. Histological and micro-computed tomography evaluations of newly formed bone after maxillary sinus augmentation using a xenograft with similar density and mineral content of bone: An experimental study in rabbits. Clin Exp Dent Res. 2018;4(6):284–90. https://doi.org/10.1002/cre2.146.

Omori Y, Ricardo Silva E, Botticelli D, Apaza Alccayhuaman KA, Lang NP, Xavier SP. Reposition of the bone plate over the antrostomy in maxillary sinus augmentation: A histomorphometric study in rabbits. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2018;29(8):821–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/clr.13292 Epub 2018 Jun 7. PubMed PMID: 29876969.

Masuda K, Silva ER, Botticelli D, Apaza Alccayhuaman KA, Xavier SP. Antrostomy Preparation for Maxillary Sinus Floor Augmentation Using Drills or a Sonic Instrument: A Microcomputed Tomography and Histomorphometric Study in Rabbits. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2019;34(4):819–27.

Masuda K, Silva ER, Apaza Alccayhuaman KA, Botticelli D, Xavier SP. Histological and microCT analyses at implants installed immediately after maxillary sinus lifting using large or small xenograft granules. An experimental study in rabbits. Accepted for publication. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. .

Moon YS, Sohn DS, Moon JW, Lee JH, Park IS, Lee JK. Comparative histomorphometric analysis of maxillary sinus augmentation with absorbable collagen membrane and osteoinductive replaceable bony window in rabbits. Implant Dent. 2014;23(1):29–36. https://doi.org/10.1097/ID.0000000000000031.

Amari Y, Botticelli D, Apaza Alccayhuaman KA, Hirota A, Silva ER, Xavier SP. Healing of the displaced bony window after sinus lifting. An experimental histologic study in rabbits. Accepted for publication. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants.

Silva LD, de Lima VN, Faverani LP, de Mendonça MR, Okamoto R, Pellizzer EP. Maxillary sinus lift surgery-with or without graft material? A systematic review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2016;45(12):1570–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijom.2016.09.023.

Al-Moraissi EA, Alkhutari AS, Abotaleb B, Altairi NH, Del Fabbro M. Do osteoconductive bone substitutes result in similar bone regeneration for maxillary sinus augmentation when compared to osteogenic and osteoinductive bone grafts? A systematic review and frequentist network meta-analysis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2020;49(1):107–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijom.2019.05.004.

Gao C, Peng S, Feng P, Shuai C. Bone biomaterials and interactions with stem cells. Bone Res. 2017;5:17059. https://doi.org/10.1038/boneres.2017.59.eCollection2017.

Canullo L, Menini M, Santori G, Rakic M, Sculean A, Pesce P. Titanium abutment surface modifications and peri-implant tissue behavior: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Oral Investig. 2020;24(3):1113–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-020-03210-x.

Canullo L, Genova T, Naenni N, Nakajima Y, Masuda K, Mussano F. Plasma of argon enhances the adhesion of murine osteoblasts on different graft materials. Ann Anat. 2018;218:265–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aanat.2018.03.005.

Canullo L, Genova T, Rakic M, Sculean A, Miron R, Muzzi M, Carossa S, Mussano F. Effects of argon plasma treatment on the osteoconductivity of bone grafting materials. Clin Oral Investig. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-019-03119-0.

Canullo L, Tallarico M, Botticelli D, Alccayhuaman KAA, Martins Neto EC, Xavier SP. Hard and soft tissue changes around implants activated using plasma of argon: A histomorphometric study in dog. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2018;29(4):389–95. https://doi.org/10.1111/clr.13134.

Hirota A, Baba S, Canullo L, Botticelli D, Samuel P., Xavier SP. Bio-activation with Argon plasma of a deproteinized bovine bone mineral used for sinus augmentation. An experimental study in rabbits. Accepted for publication. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants.

Perini A, Ferrante G, Sivolella S, Velez JU, Bengazi F, Botticelli D. Bone plate repositioned over the antrostomy after sinus floor elevation: an experimental study in sheep. Int J Implant Dent. 2020;6(1):11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40729-020-0207-1.

Russell, W. M. S. & Burch R. L. (1959). The principles of human experimental technique. London Methuen.

Lee JH, Yi GS, Lee JW, Kim DJ. Physicochemical characterization of porcine bone-derived grafting material and comparison with bovine xenografts for dental applications. J Periodontal Implant Sci. 2017;47(6):388–401. https://doi.org/10.5051/jpis.2017.47.6.388.

Figueiredo M, Henriques J, Martins G, Guerra F, Judas F, Figueiredo H. Physicochemical characterization of biomaterials commonly used in dentistry as bone substitutes--comparison with human bone. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2010;92(2):409–19. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbm.b.31529.

Iida T, Baba S, Botticelli D, Masuda K, Xavier SP. Comparison of histomorphometry and microCT after sinus augmentation using xenografts of different particle sizes in rabbits. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2020;24(1):57–64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10006-019-00813-x.

De Santis E, Lang NP, Ferreira S, Rangel Garcia I Jr, Caneva M, Botticelli D. Healing at implants installed concurrently to maxillary sinus floor elevation with Bio-Oss(®) or autologous bone grafts. A histo-morphometric study in rabbits. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2017;28(5):503–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/clr.12825..

Favero G, Viña-Almunia J, Carda C, Martín de Llano JJ, García-Mira B, Soto-Peñaloza D, Peñarrocha-Diago M, Botticelli D. Influence of the use of autogenous bone particles to close the access window after maxillary sinus floor augmentation: an experimental study in rabbits. Int J Implant Dent. 2020;6(1):9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40729-020-0206-2.

Favero V, Lang NP, Canullo L, Urbizo Velez J, Bengazi F, Botticelli D. Sinus floor elevation outcomes following perforation of the Schneiderian membrane. An experimental study in sheep. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2016;27(2):233–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/clr.12576.

Scala A, Lang NP, Velez JU, Favero R, Bengazi F, Botticelli D. Effects of a collagen membrane positioned between augmentation material and the sinus mucosa in the elevation of the maxillary sinus floor. An experimental study in sheep. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2016;27(11):1454–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/clr.12762.

Gruber R, Kandler B, Fuerst G, Fischer MB, Watzek G. Porcine sinus mucosa holds cells that respond to bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)-6 and BMP-7 with increased osteogenic differentiation in vitro. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2004;15(5):575–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0501.2004.01062.x.

Srouji S, Kizhner T, Ben David D, Riminucci M, Bianco P, Livne E. The Schneiderian membrane contains osteoprogenitor cells: in vivo and in vitro study. Calcif Tissue Int. 2009;84(2):138–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00223-008-9202-x.

Srouji S, Ben-David D, Lotan R, Riminucci M, Livne E, Bianco P. The innate osteogenic potential of the maxillary sinus (Schneiderian) membrane: an ectopic tissue transplant model simulating sinus lifting. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;39(8):793–801. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijom.2010.03.009.

Srouji S, Ben-David D, Funari A, Riminucci M, Bianco P. Evaluation of the osteoconductive potential of bone substitutes embedded with Schneiderian membrane- or maxillary bone marrow-derived osteoprogenitor cells. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2013;24(12):1288–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0501.2012.02571.x.

Botticelli D, Lang NP. Dynamics of osseointegration in various human and animal models - a comparative analysis. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2017;28(6):742–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/clr.12872.

Acknowledgements

The support in histological measurements, data interpretation, and article writing provided by Dr. Karol Alí Apaza Alccayhuaman, ARDEC Academy, Rimini, Italy, is highly appreciated. All authors thank Dr. Erick Ricardo Silva for having performed the surgical procedures.

The biomaterial was provided by Degradable Solutions AG, a Sunstar Group Company, CH-8952 Schlieren ZH, Switzerland.

Funding

The experiment was financially supported by ARDEC Academy, Rimini, Italy.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Dr. Kazushige Tanaka participated to Concept/Design, Data analysis/interpretation, Article writing, Approval of article. Dr. Daniele Botticelli participated to Concept/Design, Protocol writing, Surgical treatment, Data analysis/interpretation, Article writing, Approval of the article. Dr. Luigi Canullo participated to Concept/Design, Data analysis/interpretation, Article writing, Approval of the article. Prof. Shunsuke Baba participated Concept/Design, Critical revision of the article, Approval of article. Prof. Samuel Porfirio Xavier participated to Concept/Design, Management of the experiment, Critical revision of the article, Approval of the article. All authors have seen and approved the final version of the manuscript being submitted.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee at the School of Dentistry, of Ribeirão Preto, University of Sao Paulo (USP), with the code 2018.1.454.58.2 signed on 19 September 2018.

Consent for publication

Consent to publish was obtained from all applicable parties.

Competing interests

Kazushige Tanaka declares no competing of interest regarding this study.

Daniele Botticelli declares no competing of interest regarding this study.

Luigi Canullo, declares no competing of interest regarding this study.

Shunsuke Baba declares no competing of interest regarding this study.

Samuel P. Xavier declares no competing of interest regarding this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tanaka, K., Botticelli, D., Canullo, L. et al. New bone ingrowth into β-TCP/HA graft activated with argon plasma: a histomorphometric study on sinus lifting in rabbits. Int J Implant Dent 6, 36 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40729-020-00236-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40729-020-00236-4