Abstract

This study investigated how corporate sustainability performance can be attained through the interface of corporate ethical values and leader-member exchange, and how employees’ positive and negative behaviors can influence these relationships. A total of 310 data sets were collected and used to test our hypotheses. To assess the factorability of the variables, exploratory factor analysis was conducted, and confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to test the fit and validity of the measurement model. Then, the structural model proceeded to test the hypotheses. The results of this study found that employee behaviors can highly influence corporate sustainability performance. Depending on contextual or/and relational factors, employee behaviors can either encourage more organizational citizenship behavior or alleviate counterproductive work behavior. These findings demonstrate that it is critical not only to create an ethical working environment but also to develop quality relationships with direct managers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As the goal of corporate sustainability is to promote harmony in business and society, the manner in which organizations should respond to social and environmental concerns is a central issue in today’s retail industry, specifically in fashion (Lee and Ha-Brookshire 2017). This is because the fashion retail industry has been challenged with various destructive claims that a number of global fashion brands have created circumstances which neglect social responsibility (Goworek et al. 2012). Accordingly, many fashion retail businesses have devoted considerable effort to transforming their negative reputations, encouraging employee engagement, and to becoming even more responsible than other industries (Kanwar et al. 2012). To shift toward corporate sustainability, the stakeholder theory emphasizes the importance of paying attention to internal stakeholders, as employees’ attitudes and behaviors can both directly and indirectly impact organizations’ performance (Rupp et al. 2013). If employees perceive that they work in an ethical environment and develop better relationships with direct managers, they will be more likely to engage in more positive behaviors to promote organizational goals (Lee and Ha-Brookshire 2017; Rupp et al. 2013).

Defined as a “discretionary, not directly or explicitly recognized by the formal reward system and that in the aggregate promotes the effective functioning of the organization” (Organ 1988, p. 4), organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) may have a positive association with organizational ethical working environment and corporate sustainability performance (Lee and Ha-Brookshire 2017; Shin 2012). Conversely, counterproductive work behavior (CWB) is intentionally destructive behavior designed to hurt the justifiable interests of an organization (Gruys and Sackett 2003). Related to negative emotions such as anger, anxiety, and frustration, CWB was found to impede organizational performance from a social perspective (Chernyak-Hai and Tziner 2014). This is because CWB hampers the positive impacts of CEV and LMX on corporate sustainability performance (Chernyak-Hai and Tziner 2014). Schwartz (2013) posited that employees may perceive their employers as socially responsible organizations if they see these three elements reflected: ethical leadership, corporate ethical values, and a robust ethics program. This implies that contextual (corporate ethical values) and relational (leader-member exchange) factors may influence employees’ behaviors, which can assist organizations in shifting toward corporate sustainability.

As contextual factors, corporate ethical values (CEV) provide an important context for employees to engage in more ethical decision-making and CEV also improves organizational performance in the long run (Lee and Ha-Brookshire 2017; O’Fallon and Butterfield 2005). On the other hand, as a relational factor, leader-member exchange (LMX) has been explored to understand managerial behaviors and also to encourage employees’ motivations as related to empowerment, respect, and obligation (Chernyak-Hai and Tziner 2014; Fein et al. 2013). Previous literature has found an association between LMX and job performance (Dulebohn et al. 2012). Accordingly, high-quality LMX leads to improved work performance, which in turn results in a more objective measure of organizational performance as well as greater anticipation from value chain partners and stakeholders (Wang et al. 2005).

Given that the fashion retail industry strives to shift toward corporate sustainability, how employees feel valued by working in better and more responsible environments, and how relationships with leaders affect corporate sustainability are crucial areas to explore (Lee and Ha-Brookshire 2017; Schwartz 2013). Therefore, this study aims to investigate how negative and positive employee behaviors can be alleviated or engaged through providing an ethical working environment and quality relationships with direct managers or executives. Hence, our findings can provide crucial insights into the different dimensions of corporate sustainability to take into consideration during the strategic decision-making process.

Literature Review

Corporate sustainability and stakeholder theory

Corporate social responsibility (CSR), interchangeable with corporate sustainability, stresses an organization’s obligations to its stakeholders and how organizations should act to respond to social and environmental concerns (Baumgartner 2014). Essentially, the notion of corporate sustainability refers to the goal of an organization to fulfil the needs of its current stakeholders without diminishing its capabilities to meet the needs of future stakeholders (Dyllick and Hockerts 2002). Unlike traditional management that solely emphasizes the economic performance of an organization, corporate sustainability focuses on simultaneously protecting the environment and enhancing the welfare of society in the long run. In this regard, previous literature on CSR is closely tied to the relationship between business and society (O’Riordan and Fairbrass 2014), business ethics (Crane and Matten 2010), and the stakeholder theory (Freeman 1984).

In order to understand how the CSR practices of organizations are actually implemented, it is imperative to assess the perceptions of corporate sustainability by individual members of organizations as inner actors or/and internal stakeholders. Based on the stakeholder theory, a holistic approach that holds all members in an organization (e.g., consumers, community, investors, suppliers and employees) responsible for a common obligation towards all other beings, corporate sustainability should be incorporated into different areas of the organization (Van Marrewijk 2003). Employees’ perception toward their employer’s CSR may provide “direct and stronger implications for employees’ subsequent reactions than actual firm behaviors of which employees may or may not be aware” (Rupp et al. 2013, p. 897).

Employee behaviors

Employees play an important role in directly and indirectly influencing an organization’s performance because they “shape the organizational, social, and psychological context that serves as the catalyst for task activities and processes” (Borman and Motowidlo 1997, p. 100). Some researchers have defined these behaviors as either Organizational Citizenship Behavior (OCB) or Counterproductive Work Behavior (CWB), both of which have been extensively studied in psychology and management literature (Appelbaum et al. 2004; Ellinger and Wu 2013; Foote and Tang 2008; Gkorezis and Bellou 2016; Zheng et al. 2017).

OCB refers to employee behavior that is “discretionary, not directly or explicitly recognized by the formal reward system and that in the aggregate promotes the effective functioning of the organization” (Organ 1988, p. 4). Organ (1988) defined the two dimensions of OCB as interpersonal (OCBI), which helps others and colleagues in the organization, and organizational (OCBO), which puts more effort into achieving the organization’s goals. As OCB involves discretionary work behavior that generates a positive work context, numerous literature has posited that propositions of OCB may be enacted by “good soldiers and good actors” (Donia et al. 2016, p. 23). Employees who engage in higher levels of OCB are found to be more deeply rooted in their current organizations, as social capital is accrued from these behaviors (Becton et al. 2017). Accordingly, many studies have argued that OCB is strongly associated with affective attitudinal variables, such as employee satisfaction, organizational commitment, and decreased turnover intentions (Donia et al. 2016; Fassina et al. 2008; Hoffman et al. 2007). Predominantly explained by the social exchange theory, OCB was also found to be an outcome of quality leader-member exchange (LMX), trust among parties, and long-term relationships (Becton et al. 2017). Moreover, Valentine et al. (2011) argued that context-based factors, such as corporate ethical values and cooperative norms, could also increase and encourage OCB among employees.

Counterproductive work behavior (CWB), on the other hand, concerns employee behaviors that are intentionally performed to hurt the valid and justifiable interests of an organization (Gruys and Sackett 2003). As an employee’s expression of their dissatisfaction towards their work environment, CWB is strongly correlated with negative emotions (such as anger, anxiety, and frustration) induced by organizational constraints like injustice, stressful work environment, and job dissatisfaction (Dwayne and Greenidge 2010; Kelloway et al. 2010). According to Bennet and Robinson (2000), CWB may be voluntary and highly motivated behavior intended to harm colleagues, organizational property, and/or a company’s profitability and reputation (Ng et al. 2016; Miao et al. 2017; Spector and Fox 2010). Regarded as a collective concept that incorporates any negative workplace behaviors, CWB has been examined as aggressive, revengeful, rude, and threatening behaviors (Chernyak-Hai and Tziner 2014; Zheng et al. 2017). Thus, employees who engage in high levels of CWB tend to develop stress-related problems, a high rate of turnover intentions, lack of confidence at work, and physical and psychological pains (Chernyak-Hai and Tziner 2014). Therefore, previous research has indicated that predictors for CWB include employees’ personal traits and abilities (e.g., Dalal 2005; Dilchert et al. 2007), harsh supervision, dissatisfaction with their role, and interpersonal conflicts (Bruk-Lee and Spector 2006; Mitchell and Ambrose 2007).

Prior studies have suggested that these two types of employee behaviors may not be inter-related, meaning that they could display different relationships with antecedents (Spector et al. 2010; Spector and Fox 2010). Numerous studies have examined the relationship between CWB and OCB, as both behaviors are dimensions of job performance (Hoesni and Omar 2012). Dalal (2005) addressed that OCB and CWB were found in a low to modestly negative range. Similarly, other studies (e.g., Kelloway et al. 2002; O’Briend and Allen 2008; Sackett et al. 2006) supported this view, as OCB and CWB are considered to be distinct constructs and that both types of behaviors can possibly be engaged in at any one time.

Employee behaviors and corporate sustainability performance

Extant empirical studies (e.g., McWilliams and Siegel 2011; Luo and Bhattacharya 2006) have examined organizations’ CSR practices, particularly focusing on organizational outcomes such as customer satisfaction and financial performance. Likewise, numerous studies have primarily focused on the influences of CSR practices on employees’ attitudinal variables, such as organizational commitment (Aguilera et al. 2006; Brammer et al. 2007), turnover intentions, job satisfaction (Valentine and Fleischman 2008), and organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) (e.g. Chun et al. 2013; Evans et al. 2010; Gao and He 2016).

OCB is found to have a significant association with an organization’s ethical working environment (Shin 2012) and organizational justice. OCB recuperates organizational effectiveness (Koys 2001) and improves both organizational and individual outcomes (Podsakoff et al. 2009). However, Newman et al. (2015) found direct and positive effects of employees’ perceptions of CSR on OCB, leading to improvements in job performance. Recognized as a high-performance human resource concept, OCB mediates employee job performance as well as organizational performance in service-based organizations (Sun et al. 2007). Moreover, according to Lee and Ha‐Brookshire (2018), OCB can improve the effectiveness and flexibility of an organization’s performance through valuing the role of employees. OCB not only leads to employees’ empowerment and improves service quality, but it also motivates employees to change their goals and career directions to align with that of the organization (Bettencourt 2004; Chiang and Hsieh 2012). Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1

Organizational citizenship behavior positively influences corporate sustainability performance.

Similar to OCB, numerous organizations experience difficulties caused by volitional behavior by employees that has a detrimental effect on their organizations and stakeholders (Shin et al. 2017). This was shown in previous research indicating that deviant behavior or CWB causes devastating problems to organizations, including increased absences and turnover, as well as decreased job satisfaction and productivity (Bennett and Robinson 2000; Dalal 2005). Therefore, numerous scholars in organizational studies have explored the situational reasons that can cause CWB amongst employees in the workplace, such as organizational injustice, interpersonal conflict, and emotional stressors (Fox et al. 2001; Shin et al. 2017). Corresponding with increasing attention toward sustainability in organizational studies, many organizational scholars have explored how positive employee behaviors can be affected by CSR perceptions, which neglects the serious consequences of CWB. A recent study by Hur et al. (2018) found that CSR perceptions not only influenced OCB, but that CSR perceptions can hinder CWB amongst employees. Shin et al. (2017) supported this view that CSR perceptions can encumber such negative behaviors. Thenceforth, this leads to questions regarding reversing this relationship to explore the impacts of CWB on CSR performance. Therefore, following hypothesis was proposed:

H2

Counterproductive work behavior negatively influences corporate sustainability performance.

Antecedents of employee behaviors

Corporate ethical value

Corporate ethical value (CEV) is comprised of an organization’s policy on ethics (both formal and informal) and the moral values of individual employees within the organization (Hunt et al. 1989). As the central dimension of an organizations’ culture, CEV explains the way the organization performs its functions and maintains relationships with its stakeholders, including customers, suppliers, employees, communities and the environment (Hunt et al. 1989). Accordingly, a considerable amount of extant literature has been devoted to exploring the impact of CSR on company performance (Lopez et al. 2007; McWilliams and Siegel 2011). Chahal and Sharma (2006) posited that organizational culture and ethical values could induce profitability and market share as well as stakeholder satisfaction and retention. Choi et al. (2013) empirically demonstrated that the ethical climate of an organization is positively associated with its financial performance. Chang (2015) also demonstrated that green organizational culture has a positive impact on CSR adoption and green product innovation. Similar studies have reported that corporate ethical value may not only related to organizational performance but also positively influenced the ethical attitudes of employees and managers in the information technology (IT) sector (Jin and Drozdenko 2010).

Indeed, a recent study by Lee and Ha-Brookshire (2017) reported a strong and positive impact of ethical values on the economic and social aspects of sustainability performance in the fashion retail industry. Likewise, this study measured corporate sustainability in terms of its economic and social aspects; namely competitive performance (CP) (Madueno et al. 2016; Marin et al. 2012) and relational improvement (RI) with an organization’s primary stakeholders (Hillman and Keim 2001; Madueno et al. 2016). Therefore, the following hypotheses were proposed:

H3a

Corporate ethical values positively influence organizational citizenship behavior.

H3b

Corporate ethical values negatively influence counterproductive work behavior.

Leader-member exchange

Leader-member exchange (LMX) concerns the quality of the relationship between subordinates and supervisors in the work environment (Dansereau et al. 1975). As a dyadic relationship-based approach accentuating the relationship between leaders and followers, leaders may establish relationships at varied intensity with members in their work groups (Liden et al. 2006). A high level of LMX was found to result in improvements in employee productivity and satisfaction (Zhang et al. 2012), as well as lower turnover intentions (Harris et al. 2009). High-quality LMX signifies that relationships between managers and employees are imbued with confidence, respect, encouragement, and mutual influence, while low-quality LMX indicates rather rigid interactions, a one-directional influence (manager-employee), and partial support (Chernyak-Hai and Tziner 2014). LMX has been used as one of the primary theories to help understand managerial behavior as well as to impact employees’ drive in different aspects of organizational performance, sense of empowerment, respect and obligation (Chernyak-Hai and Tziner 2014; Fein et al. 2013).

Previous literature has indicated that LMX is positively associated with OCB (Harris et al. 2014; Illies et al. 2007; Li et al. 2010; Martin et al. 2016; Wang et al. 2005). By conducting a meta-analysis, Illies et al. (2007) found that LMX strongly influenced employees’ OCB. As individuals’ sense of being a “good citizen” links to the collective goals of the organization, high-quality relationship with managers can positively influence employees to display more OCB (Wang et al. 2005). This finding supports a meta-analytic by Hackett et al. (2003) supporting that OCB is formed in exchange with the mutual social relationship process of LMX. In the retail sector, Lindblom et al. (2015) illustrated that the perceptions of frontline employees regarding ethical leadership in their companies are strongly related to their customer orientation and in turn positively affect job satisfaction and negatively influence turnover intentions. On the other hand, although relatively little empirical evidence has suggested a negative association with CWB (Martin et al. 2016), a high degree of LMX was recommended to mitigate the negative impact of organizational injustice on CWB (Chernyak-Hai and Tziner 2014). Therefore, the following hypotheses were proposed:

H4a

Leader-member exchange positively influences organizational citizenship behavior.

H4b

Leader-member exchange negatively influences counterproductive work behavior.

Method

Data collection and sample

This study commissioned an established research firm in the U.S. to conduct an online survey for data collection between June and July 2017. The sample framework for this study was comprised of employees in the fashion or specialty retail industry in the U.S. over age 18 and who had been working with their current company for at least 1 year. A total of 310 responses were collected with no missing data or unengaged responses observed. The final sample consisted of an equal number of males and females (each 155), with almost all of the respondents (99%) ages 18–64, and more than half of them (55%) had job duties related to sales. Approximately 38% of the respondents had less than 5 years’ work experience, and around 55% of them worked for small-medium-sized enterprises (SMEs, with less than 500 employees) whilst the remaining 45% worked for a large corporation (with employees over 500). Table 1 summarizes the profiles of the respondents.

Measure and questionnaire design

All variables considered in the proposed framework were assessed using multi-item scales drawn from the literature. To mitigate the possible effect of common method bias with respect to scale endpoint commonalities and the anchoring effect, different formats of measurement scales were adopted in the set of questionnaires (Podsakoff et al. 2003).

To be specific, five items for corporate ethical values (CEV) were adapted from Baker et al. (2006) and five items for leader-member exchange (LMX) were used from Bettencourt (2004); both scales used a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“strongly agree”) to 7 (“strongly disagree”). The seven items measuring organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) were adapted from Shin (2012). The variables were conceptualized to possess a second-order factor structure with two sub-dimensions, namely: interpersonally-directed (OCB_I, 4-items) and organizationally-directed (OCB_O, 3-items). The 10 items to measure counterproductive work behavior (CWB) were adapted from Spector et al. (2010). Both OCB and CWB employed a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“never”) to 5 (“always”). Regarding corporate sustainability performance, the 20-item scale measuring MRCS that we used was developed by Jung and Ha-Brookshire (2017). The construct was conceptualized as a second-order factor structure composed of four first-order factors, namely: environmental support (EN), community support (CM), working conditions (WC), and transparency enhancement (TR). A five-point Likert-like scale (from 1 = “not doing well” to 5 = “doing very well”) was used.

To address the possible issue of common method variance (Podsakoff et al. 2003), measurements of respondents’ degree of social desirability were included in the set of questionnaires. Essentially, 10 items from the Marlowe–Crowne social desirability scale popularized by Fisher and Fick (1993) were adopted, of which four items were reverse-coded. The sum of the scores of these six items (which might range from 0 to 6) formed the composite social desirability score which was then incorporated in the structural model as a control variable for analysis. Lastly, demographic information was collected such as gender, age, marital status, ethnicity, household income level, and educational background. To ensure content validity and construct reliability, a pilot study with thirteen participants was performed prior to the formal survey. All participants confirmed their understanding of the survey’s instructions and no issues related to the measurement items were reported.

Results

Exploratory factor analysis

Prior to analyzing the measurement model, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) with maximum likelihood extraction and Promax rotation was performed for the seven items measuring OCB and the 20 items measuring CSR performance, respectively. No significant cross-loadings resulted from EFA of the two variables. OCB yielded two factors as OCB_I and OCB_O, and the corresponding KMO measure of sample adequacy was .79 while the total variance explained by the two factors was 65.68%. On the other hand, the EFA yielded four factors for corporate sustainability performance, namely: environmental support, community support, working conditions support, and transparency enhancement. The respective KMO measure of sample adequacy was .93, and the total variance explained by the four factors was 71.32%. Consequently, second-order factor structures were adopted for OCB and CSP in the measurement model.

Measurement model

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to test the fit and validity of the measurement model. The measurement model showed a good fit with indices as, \(X^{2}\) value of 773.824 (d.f. = 542; p-value < .001), a corresponding CFI of .96, a TLI of .96, an RMSEA of .037, and an SRMR of .05 at acceptable levels of model fit. All coefficients were significant and composite reliability scores of the constructs ranged from .57 to .95, exceeding the recommended standards for construct reliability (Table 2).

The convergent and discriminant validity of the measurement model was checked with the average variance extracted (AVE). The average variance extracted (AVE) of each construct was greater than .50, confirming the convergent validity of each scale (Fornell and Larcker 1981). Additionally, the AVE was greater than the squared correlation coefficients between any associated pair of constructs, supporting discriminant validity for each construct (Table 3).

The structural model

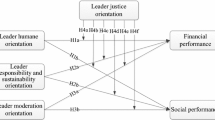

A structural model was conducted for hypothesis testing, using maximum likelihood estimation (AMOS24). The proposed model exhibited an adequate model fit (\(X^{2}\) value of of 853.276 (d.f. = 544; p-value < .001), a corresponding CFI of .95, a TLI of .94, an RMSEA of .04, and an SRMR of .07). The SEM results supported the postulated paths except for H3a. First, OCB was found to be positively correlated with corporate sustainability performance, thereby supporting H1. This indicates that employees’ OCB is important for increasing corporate sustainability performance. CWB was found to negatively impact corporate sustainability performance, thereby supporting H2. Due to the fact that CWB is action purposively taken to harm one’s company directly or indirectly, the presence of CWB hinders corporate sustainability performance. Moreover, the two antecedents, CEV and LMX, were found to be significant in developing OCB, thereby supporting H3a and H4a. This shows that the relationships with managers or/and direct supervisors is not only important but also creates an ethical culture in the working environment which is critical for OCB. On the other hand, CEV was not found to significantly impact CWB, while LMX was found to affect CWB. Therefore, H3b was not supported while H4b was supported. The SEM results for OCB are summarized in Fig. 1.

Conclusion

To achieve corporate sustainability, it is essential not to neglect the roles of employees as imperative stakeholders in enhancing an organization’s performance as they make decisions and work closely to affect the success of organizations in the long run. Since global fashion retail businesses have been involved in many different scandals relating to working environment and labor issues, which is contrary to sustainability, it is critical to understand how employees as fundamental stakeholders can impact the sustainability performance of organizations. Through conducting a nationwide survey using U.S. fashion retail employees, this study found that employees’ positive and negative behaviors could influence different aspects of corporate sustainability performance. More importantly, these behaviors were shown to have significant contextual and relational impacts.

The findings of this study provide several key implications. First, although there is increasing attention on corporate sustainability in many industries, there is limited literature exploring how employee behaviors can affect corporate sustainability performance. Considering employees as internal actors who make decisions for their organizations based on the stakeholder theory, this study is one of the few to suggest how employees can contribute to improving corporate sustainability performance. First, previous studies (e.g., Lee and Ha-Brookshire 2017; Shin 2012) have addressed that employees who engage in high levels of organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) could increase corporate sustainability performance. The findings of this study also support this notion that employees with high engagement in OCB could strongly influence corporate sustainability. On the other hand, the results of this study found that counterproductive work behavior (CWB) was found to negatively influence corporate sustainability performance. As CWB refers to intentional and voluntary behavior intended to harm the justifiable interests of an organization (Gruys and Sackett 2003), previous literature has indicated that CWB was found to negatively influence organizational performance. The findings of this study can supplement previous literature, as CWB has also had a severe impact on corporate sustainability performance in aspects of environment and community supports, information transparency, and working environments.

The findings on both types of employee behaviors confirm the stakeholder theory indicating that the role of employees in an organization is imperative as they are influential stakeholders contributing toward organizational performance. Moreover, the findings of this study supported previous literature (e.g., Dalal 2005; Kelloway et al. 2002; O’Briend and Allen 2008; Sackett et al. 2006) indicating that OCB and CWB are found in low negative correlations. This indicates that the OCB-CWB relationship can be considered as distinct constructs which can be engaged in at any one time. If organizations nurture employees with high levels of OCB, this implies that any harmful behavior toward organizations will eventually decline as employees become highly committed to the organization’s goal and form interpersonal relationships with others in the organization. Consequently, our findings underscore the importance of cultivating employees with high levels of OCB while preventing employees from engaging in CWB. In order to cultivate higher levels of OCB among employees while abandoning harmful behaviors like CWB, fashion retail industries can consider providing many opportunities for promotion, earning monetary or other incentives, commit to offering an ethical working environment, and develop good relationships with managers.

Moreover, this study found that key predictors for employee behaviors are not only relational but also contextual. First, this study found that corporate ethical values (CEV) play a central role in employees’ OCB. This finding is akin to previous studies (Lee and Ha-Brookshire 2017; Shin 2012). If the working environment is perceived by employees to be more ethical, they will tend to engage more in OCB, which leads to improved relationships with different stakeholders (Nielsen et al. 2012; Podsakoff et al. 2009). Therefore, due to the considerable number of fashion retail and other businesses attempting to shift toward sustainability, creating working environments with robust ethical values is necessary. Consequently, the study’s findings provide the insight that employees in an ethical working environment will feel more appreciable to making decisions that could be highly influential and impactful toward organizations’ long-term goals. Thus, as many global fashion retail businesses have been involved in negative and irresponsible scandals, these retail businesses should not only focus on the public image of their brands, but also on creating an ethical and responsible working environment and managers with soft skills.

Furthermore, the findings of this study report that leader-member exchange (LMX) is has a significant impact on employee behaviors. Interestingly, high and strong relationship that develop in LMX play a critical role in developing both types of employee behaviors (OCB and CWB). This entails that if employees develop trust and a two-way relationship with managers, this will stimulate more OCB and less CWB (Chernyak-Hai and Tziner 2014). As reflected through strong ties and relationships with direct managers, employees can be highly motivated and even guided to participate in OCB which will lead them to neglect CWB. This might be because as managers evaluate employees’ performance, employees may not want to lose the strong ties they have developed with managers by practicing CWB. Therefore, if managers promoted one of their employees who was highly committed to OCB, their involvement with junior employees would be highly developed as mentors and mentees. This indeed will help develop strong ties in relationships with direct managers and lead to a butterfly effect resulting in positive employee behaviors.

There are some limitations to this study, which can extend to future research opportunities. First, this study was designed as a single-source study examining the perspectives of U.S. fashion retail employees. Although it is one of few studies to explore the influences of fashion retail employees’ behaviors on corporate sustainability through contextual and relational factors, different findings on leader-member exchange may result from exploring the manager or leader’s perspective. Second, to enhance the findings on corporate sustainability performance, market or/and secondary data could be collected, thereby complimenting CSP. In this way, corporate sustainability performance becomes not just a marketing tactic but can also be considered as one of the essential strategies to embed in organizational performance.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

References

Aguilera, R., Williams, C., Conley, J., & Rupp, D. (2006). Corporate Governance and Social Responsibility: A comparative analysis of the UK and the US. Corporate Governance: An International Review,14(3), 147–158.

Appelbaum, S., Bartolomucci, N., Beaumier, E., Boulanger, J., Corrigan, R., Dore, I., et al. (2004). Organizational citizenship behaviour: A case study of culture, leadership and trust. Management Decision,42(1), 13–40.

Baker, T. L., Hunt, T. G., & Andrews, M. C. (2006). Promoting ethical behaviour and organizational citizenship behaviours: The influence of corporate ethical values. Journal of Business Research,59(7), 849–857.

Baumgartner, R. J. (2014). Managing corporate sustainability and CSR: A conceptual framework combing values, strategies and instruments contributing to sustainable development. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environment Management,21(5), 258–271.

Becton, J. B. B., Carr, J. C., Mossholder, K. W., & Walker, H. J. (2017). Differential effects of task performance, organizational citizenship behaviors. Journal of Business and Psychology,32, 495–508.

Bennett, R. J., & Robinson, S. L. (2000). Development of a measure of workplace deviance. Journal of Applied Psychology,85, 349–360.

Bettencourt, L. A. (2004). Change-oriented organizational citizenship behaviors: The direct and moderating influence of goal orientation. Journal of Retailing,80(3), 165–180.

Borman, W. C., & Motowidlo, S. J. (1997). Task performance and contextual performance: The meaning for personnel selection research. Human Performance,10, 99–109.

Brammer, S., Millington, A., & Rayton, B. (2007). The Contribution of Corporate Social Responsibility to Organizational Commitment. International Journal of Human Resource Management,18, 1701–1719.

Bruk-Lee, V., & Spector, P. E. (2006). The social stressors-counterproductive work behaviors link: Are conflicts with supervisors and coworkers the same? Journal of Occupational Health Psychology,11(2), 145–156.

Chahal, H., & Sharma, R. D. (2006). Implications of corporate social responsibility on marketing performance: A conceptual framework. Journal of Service Research,6(1), 205–216.

Chang, C. H. (2015). Proactive and reactive corporate social responsibility: antecedent and consequence. Management Decision,53(2), 451–468.

Chernyak-Hai, L., & Tziner, A. (2014). Relationships between counterproductive work behavior, perceived justice and climate, occupational status, and leader-member exchange. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology,30(1), 1–12.

Chiang, C.-F., & Hsieh, T.-S. (2012). The impacts of perceived organizational support and psychological empowerment on job performance: The mediating effects of organizational citizenship behavior. International Journal of Hospitality Management,31(1), 180–190.

Choi, B. K., Moon, H. K., & Ko, W. (2013). An organization’s ethical climate, innovation and performance: Effects of support for innovation and performance evaluation. Management Decision,51(6), 1250–1275.

Chun, J. S., Shin, Y., Choi, J. N., & Kim, M. S. (2013). How does corporate ethics contribute to firm financial performance? The mediating role of collective organizational commitment and organizational behavior. Journal of Management,39(4), 853–877.

Crane, A., & Matten, D. (2010). Business ethics. Oxford, London: Oxford University Press.

Dalal, R. S. (2005). A meta-analysis of the relationship between organizational citizenship behavior and counterproductive work behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology,90(6), 1241–1255.

Dansereau, F., Graen, G. B., & Haga, W. (1975). A vertical dyad linkage approach to leadership in formal organization. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance,13(1), 46–78.

Dilchert, S., Ones, D. S., Davis, R. D., & Rostow, C. D. (2007). Cognitive ability predicts objectively measured counterproductive work behaviors. Journal of Applied Psychology,92(3), 616–627.

Donia, M. B. L., Johns, G., & Raja, U. (2016). Good soldier or good actor? Supervisor accuracy in distinguishing between selfless and self-serving OCB motives. Journal of Business and Psychology,31, 23–32.

Dulebohn, J. H., Bommer, W. H., Liden, R. C., Brouer, R. L., & Ferris, G. R. (2012). A meta-analysis of antecedent and consequences of leader-member exchange: Integrating the past with an eye toward the future. Journal of Management,38(6), 1715–1759.

Dwayne, D., & Greenidge, D. (2010). The effect of organizational justice on contextual performance, counterproductive work behaviors, and task performance: Investigating the moderating role of ability-based emotional intelligence. International Journal of Selection and Assessment,18(1), 75–86.

Dyllick, T., & Hockerts, K. (2002). Beyond the business case for corporate sustainability. Business Strategy and the Environment,11(2), 130–141.

Ellinger, A. D., & Wu, Y. J. (2013). A survey relation between job satisfaction and organizational citizenship behavior (OCB). Management Decision,51(2), 248–262.

Evans, W.R., Gooman, J.M., & Davis, W. D. (2010). The impact of perceived corporate citizenship on organizational cynicism, OCB and employee deviance. Human Performance, 24(1), 79–97.

Fassina, N. E., Jones, D. A., & Uggerslev, K. L. (2008). Relationship clean-up time: Using meta-analysis and path analysis to clarify relationships among job satisfaction, perceived fairness, and citizenship behaviors. Journal of Management,34, 161–188.

Fein, E. C., Tziner, A., Lusky, L., & Palachy, O. (2013). Relationships between ethical climate, justice perceptions, and LMX. Leadership and Organizational Development Journal,34(2), 147–163.

Fisher, D. G., & Fick, C. (1993). Measuring social desirability: Short forms of the Marlowe-Crowne social desirability scale. Educational and Psychological Measurement,53(2), 417–424.

Foote, D. A., & Tang, T. L. P. (2008). Job satisfaction and organizational citizenship behavior (OCB): Does team commitment make a difference in self-directed teams? Management Decision,46(6), 933–947.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50.

Fox, S., Spector, P.E., & Miles, D. (2001). Counterproductive work behavior (CWB) in response to job stressors and organizational justice: Some mediator and moderator tests for autonomy and emotions. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 59(3), 291–309.

Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Marshfield: Pitman Publishing Inc.

Gao, Y., & He, W. (2016). Corporate social responsibility and employee organizational citizenship behavior: The pivotal roles of ethical leadership and organizational justice. Management Decision,55(2), 294–309.

Gkorezis, P., & Bellou, V. (2016). The relationship between workplace ostracism and information exchange: The mediating role of self-serving behavior. Management Decision,54(3), 700–713.

Goworek, H., Fisher, T., Cooper, T., Wooward, S., & Hiller, A. (2012). The sustainable clothing market an evaluation of potential strategies for UK retailers. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management,40(1), 935–955.

Gruys, M. L., & Sackett, P. R. (2003). Investigating the dimensionality of counterproductive work behavior. International Journal of Selection and Assessment,11(1), 30–41.

Hackett, R. D., Farh, J. L., Song, L. J., & Lapierre, L. M. (2003). LMX and organizational citizenship behavior: Examining the links within and across Western and Chinese samples. In G. B. Graen (Ed.), Dealing with diversity: LMX leadership: The Series (pp. 219–263). Greenwich: Information Age Publishing.

Harris, K. J., Wheeler, A. R., & Kacmar, K. M. (2009). Leader-member exchange and empowerment: Direct and interactive effects on job satisfaction, turnover intentions and performance. The Leadership Quarterly,20(3), 371–382.

Harris, T. B., Li, N., & Kirkman, B. I. (2014). Leader-member exchange (LMX) in context: How LMX differentiation and LMX relational separation attenuate LMX’s influence on OCB and turnover intention. The Leadership Quarterly,25(2), 314–328.

Hillman, A. J., & Keim, G. D. (2001). Shareholder value, stakeholder management, and social issues: What’s the bottom line? Strategic Management Journal,22(2), 125–139.

Hoffman, B. J., Blair, C. A., Meriac, J. P., & Woehr, D. J. (2007). Expanding the criterion domain? A quantitative review of the OCB literature. Journal of Applied Psychology,92, 555–566.

Hunt, S. D., Wood, V. R., & Chonko, L. B. (1989). Corporate ethical values and organizational commitment. Journal of Marketing,53(3), 79–90.

Hur, W-M., Moon, T-W., & Lee, H-G. (2018). Employee engagement in CSR initiatives and customer-directed counterproductive work behavior (CWB): The mediating roles of organizational civility norms and job calling. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 25, 1087–1098.

Illies, R., Nahrgang, J. D., & Morgeson, F. P. (2007). Leader-member exchange and citizenship behaviors: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology,92(1), 269–277.

Jin, K. G., & Drozdenko, R. G. (2010). Relationships among perceived organizational core values, corporate social responsibility, ethics, and organizational performance outcomes: An empirical study of information technology professionals. Journal of Business Ethics,92(3), 341–359.

Jung, S., & Ha-Brookshire, J. (2017). Perfect or imperfect duties? Developing a moral responsibility framework for corporate sustainability from the consumer perspective. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management,24(4), 326–340.

Kanwar, Y., Singh, A., & Kodwani, A. D. (2012). A study of job satisfaction, organizational commitment and turnover intent among the IT and ITES sector employees. Vision,16(1), 27–35.

Kelloway, E. K., Loughlin, C., Barling, J., & Nault, A. (2002). Self- reported counterproductive behaviors and organizational citizenship be- haviors: Separate but related constructs. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 10, 143–151.

Kelloway, E. K., Francis, L., Prosser, M., & Cameron, J. E. (2010). Counterproductive work behavior as protest. Human Resources Management Review,20(1), 18–25.

Lee, S. H., & Ha-Brookshire, J. (2017). Ethical climate and job attitude in fashion retail employees’ turnover intention, and perceived organizational sustainability performance. Sustainability,9(3), 465.

Lee, S. H. N., & Ha-Brookshire, J. (2018). The effect of ethical climate and employees’ organizational citizenship behavior on U.S. fashion retail organizations’ sustainability performance. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management,25(5), 939–947.

Li, N., Liang, J., & Crant, J. M. (2010). The role of proactive personality in job satisfaction and organizational citizenship behavior: A relational perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology,95(2), 395–404.

Liden, R. C., Erdogan, B., Wayne, S. J., & Sparrowe, R. T. (2006). Leader-member exchange, differentiation, and task interdependence: Implications for individual and group performance. Journal of Organizational Behavior,27(6), 723–746.

Lindblom, A., Kajalo, S., & Mitronen, L. (2015). Exploring the links between ethical leadership, customer orientation and employee outcomes in the context of retailing. Management Decision,53(7), 1642–1658.

Lopez, M. V., Garcia, A., & Rodriguez, L. (2007). Sustainable development and corporate performance: A study based on the Dow Jones Sustainability Index. Journal of Business Ethics,75(3), 285–300.

Luo, X., & Bhattacharya, C.B. (2006). Corporate social responsibility, customer satisfaction, and market value. Journal of Marketing, 70(4), 1–18

Madueno, J. H., Jorge, M. L., Conesa, I. M., & Martinez-Martinez, D. (2016). Relationship between corporate social responsibility and competitive performance in Spanish SMEs: Empirical evidence from a stakeholders’ perspective. Business Research Quarterly,19(1), 55–72.

Marin, L., Rubio, A., & Ruiz de Maya, S. (2012). Competitiveness as a strategic outcome of corporate social responsibility. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environment Management,19(6), 364–376.

Martin, R., Guillaume, Y., Thomas, G., Lee, A., & Epitropaki, O. (2016). Leader-Member Exchange (LMX) and performance: A meta-analytic review. Personnel Psychology,69(1), 67–121.

McWilliams, A., & Siegel, D. S. (2011). Creating and capturing value: Strategic corporate social responsibility, resources-based theory, and sustainable competitive advantage. Journal of Management,37(5), 1480–1495.

Miao, C., Humphrey, R. H., & Qian, S. (2017). Are the emotionally intelligent good citizens or counterproductive? A meta-analysis of emotional intelligence and its relationships with organizational citizenship behavior and counterproductive work behavior. Personality and Individual Differences, 116, 144–156.

Mitchell, M. S., & Ambrose, M. L. (2007). Abusive supervision and workplace deviance and the moderating effects of negative reciprocity beliefs. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(4), 1159–1168.

Newman, A., Nielsen, I., & Miao, Q. (2015). The impact of employee perceptions of organizational corporate social responsibility practices on job performance and organizational citizenship behavior: Evidence from the Chinese private sector. The International Journal of Human Resource Management,26(9), 1226–1242.

Ng, T.W.H., Lam, S.S.K., & Feldman, D.C. (2016). Organizational citizenship behavior and counterproductive work behavior: Do males and females differ? Journal of Vocational Behavior, 93, 11–32.

Nielsen, T. M., Bachrach, D. G., Sundstrom, E., & Halfhill, T. R. (2012). Utility of OCB: Organizational citizenship behavior and group performance in a resource allocation framework. Journal of Management,38(2), 668–694.

O’Brien, K. E., & Allen, T. D. (2008). The relative importance of correlates of organizational citizenship behavior and counterproductive work behavior using multiple sources of data. Human Performance, 21, 62–88.

O’Fallon, M. J., & Butterfield, K. D. (2005). A review of the empirical ethical decision-making literature: 1996–2003. Journal of Business Ethics,59(4), 375–413.

O’Riordan, L., & Fairbrass, J. (2014). Managing CSR stakeholder engagement: A new conceptual framework. Journal of Business Ethics,125(1), 121–145.

Organ, D. W. (1988). Organizational citizenship behavior: The good soldier syndrome. Lexington: Lexington Books.

Podsakoff, N. P., Whiting, S. W., Podsakoff, P. M., & Blume, B. D. (2009). Individual- and organizational-level consequences of organizational citizenship behaviors: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology,94(1), 122–141.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method bias in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology,88(5), 879–903.

Rupp, D. E., Shao, R., Thornton, M. A., & Skarlicki, D. P. (2013). Applicants’ and employees’ reactions to corporate social responsibility: The moderating effects of first-party justice perceptions and moral identity. Personnel Psychology,66(4), 895–933.

Sackett, P. R., Berry, C. M., Wiemann, S. A., & Laczo, R. M. (2006). Citizenship and counterproductive behavior: Clarifying relations between the two domains. Human Performance, 19(4), 441–464.

Schwartz, M. S. (2013). Developing and sustaining an ethical corporate culture: The core elements. Business Horizons,56(1), 39–50.

Shin, Y. (2012). CEO ethical leadership, ethical climate, climate strength, and collective organizational citizenship behavior. Journal of Business Ethics,108(3), 299–312.

Shin, I., Hur, W-M., Kim, M., & Kang, S. (2017). Hidden roles of CSR: Perceived corporate social responsibility as a preventive against counterproductive work behaviors. Sustainability, 9, 955. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9060955.

Spector, P. E., Bauer, J. A., & Fox, S. (2010). Measurement artifacts in the assessment of counterproductive work behavior and organizational citizenship behavior: Do we know what we think we know? Journal of Applied Psychology,95(4), 781–790.

Spector, P. E., & Fox, S. (2010). Counterproductive work behavior and organizational citizenship behavior: Are they opposite forms of active behavior? Applied Psychology: An International Review,59(1), 21–39.

Sun, L.-Y., Aryee, S., & Law, K. S. (2007). High-performance human resource practices, citizenship behavior, and organizational performance: A relational perspective. Academy of Management Journal,50(3), 558–577.

Valentine, S., Fleischman, G. (2008). Ethics Programs, Perceived Corporate Social Responsibility and Job Satisfaction. Journal of Business Ethics, 77(2), 159–172.

Valentine, S., Godkin, L., Fleischman, G. M., Kidwell, R. E., & Page, K. (2011). Corporate ethical values and altruism: The mediating role of career satisfaction. Journal of Business Ethics,101(4), 509–523.

Van Marrewijk, M. (2003). Concepts and definitions of CSR and corporate sustainability: Between agency and communion. Journal of Business Ethics,44(2), 95–105.

Wang, H., Law, K. S., Hackett, R. D., Wang, D., & Chen, Z. X. (2005). Leader-member exchange as a mediator of the relationship between transformational leadership and followers’ performance and organizational citizenship behavior. Academy of Management Journal,48(3), 420–432.

Zhang, Z., Wang, M., & Shi, J. (2012). Leader-follower congruence in proactive personality and work outcomes: The mediating role of leader-member exchange. Academy of Management Journal,55(1), 111–130.

Zheng, W., Wu, Y. C. J., Chen, X. C., & Lin, S. J. (2017). Why do employees have counterproductive work behavior? The role of founder’s Machiavellianism and the corporate culture in China. Management Decision,55(3), 563–578.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was provided for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SL developed the manuscript from the introduction to the discussion. The author read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares that no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, S.H. Achieving corporate sustainability performance: The influence of corporate ethical value, and leader-member exchange on employee behaviors and organizational performance. Fash Text 7, 25 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40691-020-00213-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40691-020-00213-w