Abstract

Background

To report a case of bilateral benign reactive lymphoid hyperplasia (BRLH) of the conjunctiva treated with oral doxycycline and perform review of the literature evaluating the presentation, treatment and risk of transformation to lymphoma.

Case presentation

A case report is described and review of the literature from January 1975 to January 2019 was performed. A 30-year-old man presented with bilateral enlarging fleshy pink medial canthal conjunctival lesions. Incisional biopsy revealed BRLH. Oral doxycycline was initiated (100 mg two times a day) for a total of 2 months. Both lesions decreased in size significantly at the patient’s two-month follow up visit. The residual lesion in the right eye was excised along with an adjacent pterygium and the patient has been free of recurrence for the past 1.5 years. The lesion in the left eye has remained stable in size after cessation of the oral doxycycline. A total of 235 cases of conjunctival BRLH were identified in our literature search. The mean age at diagnosis was 35.2 years (range, 5 to 91 years). BRLH lesions were unilateral in 75% of patients and bilateral in 25% of them. Seven patients (2.9%) had a concurrent Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection at the time of lesion appearance. The most common treatments were surgical excision (155/235 or 65.9%) and corticosteroids (30/235 or 12.7%), while 14% (33/235) of the patients were observed and 4.6% (11/235) received external beam radiotherapy alone. Recurrence occurred in ten patients (10/235 or 4.2%), of whom five had undergone surgical excision alone, two excision followed by external beam radiotherapy, one excision and oral corticosteroids, one radiotherapy alone and one had been treated with topical corticosteroids. Overall, only 2 of the 235 reported cases (0.8%) developed malignancy, one localized to the conjunctiva and one systemic.

Conclusions

Benign reactive lymphoid hyperplasia is one of the lymphoproliferative disorders of the conjunctiva and ocular adnexa. Extensive literature review shows that most cases are treated with surgery, steroids or observation. Oral doxycycline may be considered an alternative non-invasive treatment of BRLH conjunctival lesions. BRLH lesions warrant careful follow up as they can rarely transform into conjunctival or systemic lymphoma.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Benign reactive lymphoid hyperplasia (BLRH) of the conjunctiva is a rare, lymphoproliferative process that belongs to the broad spectrum of ocular adnexal lymphocytic infiltrative disorders [1,2,3]. It exhibits a polyclonal proliferation and presents in three different histologic types: follicular, diffuse and sheet-like [4]. The exact etiology and pathogenesis of benign reactive lymphoid hyperplasia (BRLH) remains unknown. However, BRLH is thought to result from a chronic inflammatory response of lymphoid cells to antigenic stimulation [5, 6]. The disorder displays a predilection for the male gender and the most common site of involvement is the nasal conjunctiva [1, 6,7,8,9,10,11]. Due to the clinical resemblance of BRLH to conjunctival lymphoma and the potential risk of malignant transformation, thorough examination and assessment of such lesions is warranted [1,2,3,4, 8, 9, 12, 13]. Various modalities have been used in the treatment of BRLH lesions such as surgical excision, topical, intralesional and/or oral corticosteroids, topical cyclosporine, topical interferon α2b, radiotherapy and observation [1, 2, 4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12, 14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38]. However, there is no established treatment protocol or consensus among experts as to how to manage BRLH lesions. Herein, we report a case of a 30-year-old man with bilateral benign reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of the conjunctiva treated with oral doxycycline and performed a literature review of all reported BRLH cases as to their presentation, treatment, and risk of recurrence and/or transformation to conjunctival or systemic lymphoma.

Case presentation

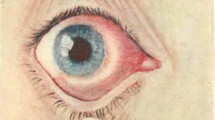

A 30-year-old man presented to the cornea service at the Athens Vision Eye Institute for evaluation of a new rapidly enlarging lesion in his right eye over the last 6 months. His past medical history was significant for Escherichia coli prostatitis 1 year prior to presentation. He had significant sun exposure since childhood, and he worked as a skipper in a sailboat for the last 12 years. His best-corrected vision was 20/20 in both eyes. Upon examination of the right eye, a fleshy pink conjunctival lesion was noted in the medial canthal area (Fig. 1a). In addition, a pterygium-type lesion encroaching on the cornea was noted. Examination of the left eye revealed a smaller fleshy pink conjunctival lesion in the medial canthus (Fig. 2a). High resolution anterior segment optical coherence tomography (OCT) (Optovue Avanti, Fremont, CA, USA) of the bilateral medial canthal lesions revealed homogeneous hyporeflective lesions with thin overlying epithelium (Figs 1b, 2b). Upon further questioning the patient and his family, they reported the presence of the bilateral medial canthal lesions since the patient was a teenager, but the patient had never sought ophthalmic care. The pterygium had been present for 1.5 years and the corresponding OCT revealed mild hyper-reflectivity of the otherwise thin epithelium with underlying subepithelial hyper-reflective “stringy” tissue.

Slit lamp photograph and high resolution anterior segment OCT of the patient’s right eye. a A gelatinous, fleshy, firm, pink conjunctival lesion (asterisk) is present in the medial canthal area of the right eye and a pterygium-type lesion with a leukoplakic head encroaching on the cornea adjacent to it (arrow). b High resolution anterior segment OCT reveals a homogeneous hyporeflective lesion (asterisk) with thin overlying epithelium in the medial canthal area of the right eye. The inset indicates the level of the scan. c Slit lamp photograph of the right eye after 2 months of oral doxycycline 100 mg twice a day. The pterygium (arrow) remains unchanged while the nasal BRLH lesion (asterisk) has decreased in size and appears flatter and smaller. d High resolution anterior segment OCT confirms the reduced size of the nasal BRLH lesion (asterisk) after 2 months of oral doxycycline. The inset indicates the level of the scan

Slit lamp photograph and high resolution anterior segment OCT of the patient’s right eye. a A gelatinous, fleshy, firm, pink conjunctival lesion (asterisk) is seen in the medial canthal area of the left eye. b High resolution anterior segment OCT reveals a homogeneous hyporeflective lesion (asterisk) with thin overlying epithelium in the medial canthal area of the left eye. The inset indicates the level of the scan. c Slit lamp photograph of the left eye after 2 months of oral doxycycline 100 mg twice a day. Similar to the right eye, the nasal BRLH lesion (asterisk) has decreased in size and appears flatter and smaller. d High resolution anterior segment OCT confirms the reduced size of the nasal BRLH lesion (asterisk) after 2 months of oral doxycycline. The inset indicates the level of the scan

Small incisional biopsies (2 mm in diameter) of the medial canthal lesions were undertaken and samples were submitted both in formalin and as fresh tissue for flow cytometry. The slightly atypically appearing pterygium was also biopsied. The patient was started on oral doxycycline 100 mg two times a day. Histopathology of the medial canthal lesions revealed lymphoid follicles of variable size that were composed of a polymorphic population of lymphocytes, dendritic cells and tingible body macrophages. Immunohistochemical staining was positive for CD20, CD3, Bcl-6, CD10 and Ki-67, and negative for Bcl-2 and Cyclin D1 (Fig. 3). Flow cytometry showed a polyclonal population of lymphocytes in both medial canthal lesions. Finally, histopathology of the other lesion in the patient’s right eye revealed elastotic degeneration consistent with pterygium. Oral doxycycline was continued for a total of 2 months. The medial canthal lesions continued to shrink as evidenced both on clinical exam (Figs. 1c, 2c) and high resolution anterior segment OCT (Figs. 1d, 2d). A month later, the patient requested surgical excision of the pterygium for cosmetic reasons and the residual medial canthal lesion in the right eye was also removed. He is free of recurrence of the BRLH for the past 1.5 years. The residual medial canthal lesion in the left eye has not increased in size since stopping the oral doxycycline.

Histopathology of the incisional medical canthal biopsy specimen from the patient’s right eye. a Hematoxylin-eosin staining of lymphoid follicles composed of small cells with mitotic figures and tingible body macrophages. (× 100 magnification) (b) Dense CD20 staining of B cells. (× 100 magnification) (c) CD3 staining of T cells within the follicles and in the interfollicular zones. (× 100 magnification)

Literature review

A PubMed search of articles published between January 1975 and January 2019 on the diagnosis and management of benign reactive lymphoid hyperplasia was performed. Searches included a combination of the following terms: “benign reactive lymphoid hyperplasia”, “conjunctival lymphoid hyperplasia”, “conjunctival lymphoma,” “ocular adnexal lymphoma,” conjunctival lymphoproliferative lesion", “conjunctival lymphoid lesion”, “doxycycline”, and “Chlamydia psittaci.” The resulting articles and references therein were then reviewed for pertinence.

Literature review revealed 235 reported cases of BRLH in 36 published studies, which are presented in Table 1 [1, 2, 4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12, 14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38]. The mean age at diagnosis of all reported cases was 35.2 years (range, 5 to 91 years), 54% of the patients whose gender was reported were male (100/186), and 46% were female (86/186). BRLH lesions were unilateral in 75% (78/104) of the patients in whom lesion location was reported and bilateral in 25% (26/104) of them. Patients were followed for a mean of 37.3 months (range, 1 month to 14 years). The primary presenting signs and symptoms included irritation and foreign body sensation (15% or 21/138), and redness and swelling (69% or 95/138), while a significant number of patients were asymptomatic (16% or 22/138).

In terms of lesion location, more than half of the lesions involved the nasal bulbar conjunctiva, one third of them involved the caruncle and plica semilunaris, while the rest of them were located in the fornix and tarsal conjunctiva. Eight patients had enlarged painless pre- or post-auricular lymph nodes at presentation and two presented with enlarged painless submental lymph nodes [5, 6, 11]. Moreover, six patients had concurrent (n = 4) or recent (n = 2) infectious mononucleosis with generalized lymphadenopathy, fever, tonsillitis and positive Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) serology [22, 34,35,36,37,38]. Other than in the aforementioned six patients, testing for infectious agents in BRLH samples has only been performed in a total of 12 cases (5.2% or 12/229) [6, 10, 38] and has been negative except for one patient with a positive histopathology for EBV latent membrane protein without an obvious clinical history of infectious mononucleosis [38]. In the study by AlAkeely et al., only 5 of the 24 cases were tested by immunohistochemistry for herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 1 (n = 3), HSV type 2 (n = 3), Cytomegalovirus (CMV) (n = 3), H. pylori (n = 3) and EBV (n = 3) due to limited tissue availability and were all negative [6]. In the study by Herwig et al., all six BRLH samples that were tested by PCR for Chlamydia species (C. trachomatis, C. psittaci, C. pneumoniae) and EBV were also negative [10]. None of the 7 patients with either positive EBV serology or immunohistochemistry developed conjunctival or systemic lymphoma at a median follow up of 8 months (range, 1–24) [22, 34,35,36,37,38]. Overall, only 2 of the 235 reported cases (0.08%) developed conjunctival (n = 1, 12) or systemic lymphoma (n = 1) [1]. The patient who developed extra-nodal marginal zone (EMZL) B cell conjunctival lymphoma from BRLH in the right eye was a 35-year old woman who was already diagnosed with EMZL in her left eye 11 months prior [12].

In terms of treatment, review of the reported cases of BRLH (Table 1) revealed that the vast majority of the patients (65.9% or 155/235) were treated with surgical excision of the lesion(s), while the second most common approach was observation alone (14% or 33/235). Corticosteroids (topical, intralesional, subconjunctival, and/or oral) and external beam radiotherapy were used in 12.7% (30/235) and 4.6% (11/235) of the patients, respectively. In 5.5% (13/235) of patients, excision was followed by external beam radiotherapy and in 1.3% (3/235) of patients, a combination of oral corticosteroids and surgical excision was used. Apart from the aforementioned traditional therapies, new treatments have emerged over the last few years including subconjunctival injections with anti-VEGF agents [31], topical cyclosporine 0.05% [29], and topical interferon 1 MIU/mL drops [30].

For the 96 patients for whom information on response to treatment were available, 79 (82.3%) experienced a complete response, while 17 (17.7%) only a partial response. (Table 1) Fifty-two of these 96 patients (54.1%) underwent excisional biopsy of the BRLH lesions; two of them had residual lesions, which were observed [5, 25], and two received a post-operative course of oral corticosteroids, which failed to eradicate the lesions [5, 19]. Nine patients (9/96 or 9.3%) were treated with topical corticosteroids; only one patient showed a complete response [14] while the rest of the patients experienced a partial response [2, 6, 15]. Two patients treated with topical antihistamines and one patient treated with a topical antibiotic ointment also had a partial response and their lesions were subsequently excised [6]. In addition, the two patients treated with topical cyclosporine [29] or interferon [30] responded partially as well. Finally, in nine patients (9.3%), the lesions were observed and resolved completely [11, 22, 32, 34,35,36, 38]; six of these 9 patients had positive EBV serology [22, 34,35,36, 38] and one had concurrent EBV-negative tonsillar enlargement [32].

Complications from treatment occurred in two cases (0.85% or 2/235). A 14-year old boy with unilateral BRLH that was treated with oral methylprednisolone (1.5 mg/kg/day) for 2 months developed post-steroid acne, which subsided a few weeks after treatment cessation [18]. The second patient developed alopecia while on topical interferon drops, which resolved upon completion of the treatment regimen [30]. Lesion recurrence was observed in 10 patients (4.2%), of whom five (2.1%) had undergone surgical excision alone [6, 11], two (0.8%) excision followed by external beam radiotherapy, one excision and oral corticosteroids (0.4%), one radiotherapy alone (0.4%) and one (0.4%) had been treated with topical corticosteroids [2].

Discussion

BRLH is a rare, lymphoproliferative disorder of uncertain etiology that usually appears as a salmon-colored subepithelial lesion in the nasal conjunctiva [1, 2, 6]. The differential diagnosis of BRLH lesions includes a wide spectrum of disorders ranging from infections (e.g., Epstein–Barr virus, toxoplasmosis, bartonella) to sarcoidosis and amyloidosis to more aggressive and malignant processes such as atypical lymphoid hyperplasia, conjunctival lymphoma, Ewing sarcoma, Burkitt’s lymphoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, systemic leukemia and/or lymphoma and squamous cell carcinoma. Therefore, proper diagnosis of such lesions calls for a thorough molecular and histopathological assessment to be performed [1,2,3,4].

BRLH lesions exhibit reactive lymphoid follicles composed of follicular dendritic cell meshwork, small T-lymphocytes and a polymorphic population of centroblasts and centrocytes of varying sizes. Small mature lymphocytes usually populate the interfollicular zones [4, 6]. These follicles usually present distinct borders, variable size and irregular shape and are divided by wide interfollicular areas with prominent mantle zones [4, 7]. In contrast, neoplastic follicles are more closely packed together, do not vary in size and shape, and their mantle zones may not be evident [4, 7]. Moreover, in the majority of cases, RLH lesions are characterized by polyclonality, as well as the absence of Dutcher bodies and cytologic atypia, nonetheless, these features only favor the diagnosis of the disease and are not pathognomonic [2, 7, 26]. Finally, as far as immunohistochemistry is concerned, the Bcl-2 marker plays a crucial role in differentiating BRLH from follicular lymphoma, as it is usually elevated in follicular lymphoma and negative in BRLH [4, 6].

The pathogenesis of conjunctival BRLH remains unknown. It is thought that chronic antigenic stimulation possibly has a role in tumor appearance [6]. Infectious agents (e.g., HIV, EBV), immunological processes (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis, Sjogren’s syndrome) and ocular allergy have been associated with chronic inflammation of the conjunctiva, inducing the development of BRLH [20, 22, 34,35,36,37,38,39]. A correlation between infection with Chlamydia psittaci and the presence of ocular adnexal lymphoma has been reported in the past, though there is significant geographical variability even within regions of the same country [40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48]. Reported prevalence rates of C. psittaci associations with ocular adnexal lymphoma range from 0% in the United States, Japan and the Netherlands to 10–12% in the United Kingdom, China, and Cuba, 47–54% in Austria, Germany and Hungary and 75–87% in South Korea and Italy [41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59]. Interestingly, in cases of conjunctival lymphoma, doxycycline has been effective in lesions that were both Chlamydia positive and Chlamydia negative [44, 58,59,60]. It has been hypothesized that the doxycycline effect may be due to its anti-inflammatory action rather than an antibiotic one [44, 58,59,60]. However, as far as conjunctival BRLH is concerned, a correlation with Chlamydia has not been clearly established [10]. In the Italian study by Ferreri et al., 3 of 26 “reactive lymphadenopathy” samples were positive for C. psittaci DNA, though it is not specified whether these samples were from conjunctival or from orbital/lacrimal gland lesions [40]. On the other hand, in two studies from Japan, none of the seven reactive lymphoid hyperplasias of the ocular adnexa were positive for C. psittaci [51, 52]. Similarly, none of the two conjunctival BRLH cases from the northeastern United States were positive for C. psittaci DNA [55]. Consequently, the role of C. psittaci in ocular adnexal lymphoproliferative disorders still remains controversial.

Conjunctival BRLH represents the benign end of the spectrum of lymphoproliferative conjunctival lesions, while conjunctival lymphoma is at the malignant end of the spectrum. Differentiation between such malignant and benign lymphoid lesions presents a diagnostic challenge as the majority of patients with either lesion can present with the same constellation of signs and symptoms [1, 2, 27]. Histopathological evaluation with immunohistochemistry, flow cytometry and molecular diagnostics, such as PCR-based immunoglobulin heavy chain (IgH, IgK) gene rearrangement studies can distinguish BRLH from true lymphomas [3, 6, 61, 62].

An additional challenge that BRLH conjunctival lesions pose to the clinician is their potential to develop into conjunctival lymphoma. When compared to BRLH lesions in the orbit, lesions in the conjunctiva have been associated with a lower incidence of transformation to lymphoma [4, 6, 15, 16, 24, 25, 27, 33, 63, 64]. In our review of the literature, only 2 of the 235 reported cases (0.8%) developed malignancy, one localized to the conjunctiva [12] and one systemic [1].

To date, there is no consensus among ocular surface specialists as to the management of conjunctival BRLH lesions. Surgical excision, despite its curative and diagnostic role, is considered by some to be an unnecessary and potentially harmful procedure for a localized and benign disease such as BRLH, especially when concerning pediatric patients [25, 28]. Corticosteroids, despite being an inexpensive solution, are associated with slow regression and poor response especially in residual lesions, with side effects including ocular hypertension and cataract formation [4, 5, 16, 29]. Finally, external beam radiotherapy carries the risk of cataract, dry eye, and rarely, radiation-related retinopathy [5, 27, 29].

In our case, we administered oral doxycycline for 2 months. Doxycycline was chosen because of its track record of being effective both in Chlamydia positive and Chlamydia negative ocular adnexal malignant lymphomas, likely due to its anti-inflammatory action, as discussed previously [44, 58,59,60]. Since BRLH is also thought to result from chronic antigenic stimulation, we discussed with the patient the off-label use of oral doxycycline. While the patient had a good clinical response in both eyes, the patient desired pterygium excision for cosmetic reasons and thus both lesions were removed from the right eye, and the small residual lesion in the left eye was observed. There has been no lesion recurrence in the right eye and no growth of the residual lesion in the left eye over the last 1.5 years. No adverse effects were observed. To our knowledge, this is the first report on the use of oral doxycycline for BRLH. Doxycycline’s combined antibiotic and anti-inflammatory action, low cost and fewer topical side effects than corticosteroids render it a good alternative in patients with BRLH. It should be noted, though, that the use of oral doxycycline is contraindicated in children under 8 years of age, as well as during pregnancy and breast-feeding. Similar to most cases treated with topical corticosteroids alone, topical antihistamines, cyclosporine or interferon (see Results section and references 2, 6, 14, 15, 29, 30), oral doxycycline resulted in a partial yet sustainable response.

Conclusions

In summary, we present the first reported case of biopsy-proven BRLH that responded partially to 2 months of oral doxycycline at a dosing of 100 mg twice daily. Similar to conjunctival lymphoma, some cases of BRLH may be responsive to this simple, non-invasive intervention. The prognosis for BRLH is overall favorable based on our review of all published reports, but a small risk of malignant transformation is possible, and thus patients should have long term follow up. Further studies are required to confirm the beneficial role of oral doxycycline in the management of BRLH lesions.

Availability of data and materials

Data and materials supporting the results reported in the manuscript are available upon request.

References

Shields CL, Shields JA, Carvalho C, Rundle P, Smith AF. Conjunctival lymphoid tumors: clinical analysis of 117 cases and relationship to systemic lymphoma. Ophthalmology. 2001;108(5):979–84.

Coupland SE, Krause L, Delecluse HJ, Anagnostopoulos I, Foss HD, Hummel M, et al. Lymphoproliferative lesions of the ocular adnexa. Analysis of 112 cases. Ophthalmology. 1998;105(8):1430–41.

Sharara N, Holden JT, Wojno TH, Feinberg AS, Grossniklaus HE. Ocular adnexal lymphoid proliferations: clinical, histologic, flow cytometric, and molecular analysis of forty-three cases. Ophthalmology. 2003;110(6):1245–54.

Stacy RC, Jakobiec FA, Schoenfield L, Singh AD. Unifocal and multifocal reactive lymphoid hyperplasia vs follicular lymphoma of the ocular adnexa. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010;150(3):412–26.e1.

McLeod SD, Edward DP. Benign lymphoid hyperplasia of the conjunctiva in children. Arch Ophthalmol. 1999;117(6):832–5.

AlAkeely AG, Alkatan HM, Alsuhaibani AH, AlKhalidi H, Safieh LA, Coupland SE, et al. Benign reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of the conjunctiva in childhood. Br J Ophthalmol. 2017;101(7):933–9.

Bagheri A, Babsharif B, Yazdani S, Rezaee Kanavi M. Benign reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of the caruncle and plica: report of 5 cases. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;23(6):473–6.

Shields CL, Alset AE, Boal NS, Casey MG, Knapp AN, Sugarman JA, et al. Conjunctival tumors in 5002 cases. Comparative analysis of benign versus malignant counterparts. The 2016 James D. Allen lecture. Am J Ophthalmol. 2017;173:106–33.

Shields CL, Demirci H, Karatza E, Shields JA. Clinical survey of 1643 melanocytic and nonmelanocytic conjunctival tumors. Ophthalmology. 2004;111(9):1747–54.

Herwig MC, Fassunke J, Merkelbach-Bruse S, Holz FG, Fischer HP, Loeffler KU. Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of the ocular surface: clinicopathologic features and search for infectious agents. Acta Ophthalmol. 2012;90(4):e331–2.

Sigelman J, Jakobiec FA. Lymphoid lesions of the conjunctiva: relation of histopathology to clinical outcome. Ophthalmology. 1978;85(8):818–43.

Fukuhara J, Kase S, Noda M, Ishijima K, Yamamoto T, Ishida S. Conjunctival lymphoma arising from reactive lymphoid hyperplasia. World J Surg Oncol. 2012;10:194.

Grossniklaus HE, Green WR, Luckenbach M, Chan CC. Conjunctival lesions in adults. A clinical and histopathologic review. Cornea. 1987;6(2):78–116.

Moraes BRM, Nascimento MVDD, Neto EDDS, Santo RM. Topical steroids eye drops in conjunctival reactive lymphoid hyperplasia: case report. Medicine. 2017;96(47):e8656.

Ioannidis AS, Rai P, Mulholland B. Conjunctival lymphoid hyperplasia presenting with bilateral panuveitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;139(3):566–8.

Ahmed TY, Agarwal PK, Roberts F, Diaper CJ. Periocular steroids in conjunctival reactive lymphoid hyperplasia, a new approach? Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2011;39(6):576–7.

Telander DG, Lee TZ, Pambuccian SE, Huang AJ. Subconjunctival corticosteroids for benign lymphoid hyperplasia. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89(6):770–1.

Brazert A, Gotz-Wieckowska A. Positive response to methylprednisolone in a child with reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of the conjunctiva. Semin Ophthalmol. 2015;30(5–6):446–9.

Nivean P, Nivean M, Ayshwaria B. Conjunctival reactive lymphoid hyperplasia - a rare case report. Int J Oc Oncol Oculopl. 2017;3(2):153–5.

Reddy S, Finger PT, Chynn EW, Iacob CE. Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia one month after LASIK surgery. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2006;244(4):529–31.

Knowles DM, Jakobiec FA, McNally L, Burke JS. Lymphoid hyperplasia and malignant lymphoma occurring in the ocular adnexa (orbit, conjunctiva, and eyelids): a prospective multiparametric analysis of 108 cases during 1977 to 1987. Hum Pathol. 1990;21(9):959–73.

Hundsdoerfer P, Overberg US, Henze G, Coupland SE, Schulte M, Bleckmann H. Conjunctival tumour as the primary manifestation of infectious mononucleosis in a 12 year old girl. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000;84(5):546.

Rofail M, Lee LR, Whitehead K. Conjunctival benign reactive lymphoid hyperplasia associated with myopic scleral thinning. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2005;33(1):73–5.

Kim P, Macken PL, Palfreeman S, Rawlinson WD, Martin F. Bilateral benign lymphoid hyperplasia of the conjunctiva in a paediatric patient. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2005;33(3):285–7.

Lam K, Brownstein S, Jastrzebski A, Jordan DR, Burns BF. Bilateral benign reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of the conjunctiva in a pediatric patient. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2011;48:e69–71.

Koay AC, Wong KT, Subrayan V. Benign reactive lymphoid hyperplasia affecting both the conjunctiva and the cornea. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2012;250(5):775–7.

Al-Mujaini A, Wali U, Ganesh A, Al-Hadabi I, Burney I. Ocular adnexal reactive lymphoid hyperplasia in children. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2012;19(4):406–9.

Beykin G, Pe'er J, Amir G, Frenkel S. Paediatric and adolescent elevated conjunctival lesions in the plical area: lymphoma or reactive lymphoid hyperplasia? Br J Ophthalmol. 2014;98(5):645–50.

Parikh RN, Sandhu HS, Massaro-Giordano G, Goldstein SM, O'Brien JM. Benign reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of the conjunctiva treated with cyclosporine. Cornea. 2018;37(2):255–7.

Finger PT, Reichstein D. Interferon alpha eye drops: treatment of atypical lymphoid hyperplasia with secondary alopecia. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007;91(8):1085–6.

Oh DH, Chun YS, Kim JC. A case of ocular benign lymphoid hyperplasia treated with bevacizumab injection. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2011;25(1):57–9.

Tang J, Rodgers IR, Basham KL, Goh J. Rare case of exuberant benign lymphoid hyperplasia involving the conjunctiva, caruncle, and plica in a child with tonsilar enlargement. J AAPOS. 2003;7(4):293–4.

Mannami T, Yoshino T, Oshima K, Takase S, Kondo E, Ohara N, et al. Clinical, histopathological, and immunogenetic analysis of ocular adnexal lymphoproliferative disorders: characterization of malt lymphoma and reactive lymphoid hyperplasia. Mod Pathol. 2001;14(7):641–9.

Gardner BP, Margolis TP, Mondino BJ. Conjunctival lymphocytic nodule associated with the Epstein-Barr virus. Am J Ophthalmol. 1991;112(5):567–71.

Meisler DM, Bosworth DE, Krachmer JH. Ocular infectious mononucleosis manifested as Parinaud's oculoglandular syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 1981;92(5):722–6.

Urbak SF. Infectious mononucleosis presenting as a unilateral conjunctival tumour. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh). 1993;71(1):133–5.

Vaivanijkul J, Boonsiri K. Conjunctival tumor caused by Epstein-Barr virus-related infectious mononucleosis: case report and review of literature. Orbit. 2017;36(2):91–4.

Feinberg AS, Spraul CW, Holden JT, Grossniklaus HE. Conjunctival lymphocytic infiltrates associated with Epstein-Barr virus. Ophthalmology. 2000;107(1):159–63.

Kubota T, Moritani S. High incidence of autoimmune disease in Japanese patients with ocular adnexal reactive lymphoid hyperplasia. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;144(1):148–9.

Ferreri AJ, Guidoboni M, Ponzoni M, De Conciliis C, Dell’Oro S, Fleischhauer K, et al. Evidence for an association between Chlamydia psittaci and ocular adnexal lymphomas. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96(8):586–94.

Ferreri AJ, Dolcetti R, Magnino S, Doglioni C, Ponzoni M. Chlamydial infection: the link with ocular adnexal lymphomas. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2009;6(11):658–69.

Aigelsreiter A, Leitner E, Deutsch AJ, Kessler HH, Stelzl E, Beham-Schmid C, et al. Chlamydia psittaci in MALT lymphomas of ocular adnexals: the Austrian experience. Leuk Res. 2008;32(8):1292–4.

Gracia E, Froesch P, Mazzucchelli L, Martin V, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Jiménez J, et al. Low prevalence of Chlamydia psittaci in ocular adnexal lymphomas from Cuban patients. Leuk Lymphoma. 2007;48(1):104–8.

Ferreri AJ, Ponzoni M, Guidoboni M, Resti AG, Politi LS, Cortelazzo S, et al. Bacteria-eradicating therapy with doxycycline in ocular adnexal MALT lymphoma: a multicenter prospective trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98(19):1375–82.

Ferreri AJ, Dolcetti R, Dognini GP, Malabarba L, Vicari N, Pasini E, et al. Chlamydophila psittaci is viable and infectious in the conjunctiva and peripheral blood of patients with ocular adnexal lymphoma: results of a single-center prospective case-control study. Int J Cancer. 2008;123(5):1089–93.

Ponzoni M, Ferreri AJ, Guidoboni M, Lettini AA, Cangi MG, Pasini E, et al. Chlamydia infection and lymphomas: association beyond ocular adnexal lymphomas highlighted by multiple detection methods. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(18):5794–800.

Yoo C, Ryu MH, Huh J, Park JH, Kang HJ, Ahn HS, et al. Chlamydia psittaci infection and clinicopathologic analysis of ocular adnexal lymphomas in Korea. Am J Hematol. 2007;82(9):821–3.

Chanudet E, Zhou Y, Bacon CM, Wotherspoon AC, Müller-Hermelink HK, Adam P, et al. Chlamydia psittaci is variably associated with ocular adnexal MALT lymphoma in different geographical regions. J Pathol. 2006;209(3):344–51.

de Cremoux P, Subtil A, Ferreri AJ, Vincent-Salomon A, Ponzoni M, Chaoui D, et al. Re: Evidence for an association between Chlamydia psittaci and ocular adnexal lymphomas. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98(5):365–6.

Goebel N, Serr A, Mittelviefhaus H, Reinhard T, Bogdan C, Auw-Haedrich C. Chlamydia psittaci, helicobacter pylori and ocular adnexal lymphoma-is there an association? The German experience. Leuk Res. 2007;31(10):1450–2.

Daibata M, Nemoto Y, Togitani K, Fukushima A, Ueno H, Ouchi K, et al. Absence of Chlamydia psittaci in ocular adnexal lymphoma from Japanese patients. Br J Haematol. 2006;132(5):651–2.

Liu YC, Ohyashiki JH, Ito Y, Iwaya K, Serizawa H, Mukai K, et al. Chlamydia psittaci in ocular adnexal lymphoma: Japanese experience. Leuk Res. 2006;30(12):1587–9.

Mulder MM, Heddema ER, Pannekoek Y, Faridpooya K, Oud ME, Schilder-Tol E, et al. No evidence for an association of ocular adnexal lymphoma with Chlamydia psittaci in a cohort of patients from the Netherlands. Leuk Res. 2006;30(10):1305–7.

Rosado MF, Byrne GE Jr, Ding F, Fields KA, Ruiz P, Dubovy SR, et al. Ocular adnexal lymphoma: a clinicopathologic study of a large cohort of patients with no evidence for an association with Chlamydia psittaci. Blood. 2006;107(2):467–72.

Vargas RL, Fallone E, Felgar RE, Friedberg JW, Arbini AA, Andersen AA, et al. Is there an association between ocular adnexal lymphoma and infection with Chlamydia psittaci? The University of Rochester experience. Leuk Res. 2006;30(5):547–51.

Ruiz A, Reischl U, Swerdlow SH, Hartke M, Streubel B, Procop G, et al. Extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphomas of the ocular adnexa: multiparameter analysis of 34 cases including interphase molecular cytogenetics and PCR for Chlamydia psittaci. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31(5):792–802.

Zhang GS, Winter JN, Variakojis D, Reich S, Lissner GS, Bryar P, et al. Lack of an association between Chlamydia psittaci and ocular adnexal lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2007;48(3):577–83.

Ferreri AJ, Govi S, Pasini E, Mappa S, Bertoni F, Zaja F, et al. Chlamydophila psittaci eradication with doxycycline as first-line targeted therapy for ocular adnexae lymphoma: final results of an international phase II trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(24):2988–94.

Husain A, Roberts D, Pro B, McLaughlin P, Esmaeli B. Meta-analyses of the association between Chlamydia psittaci and ocular adnexal lymphoma and the response of ocular adnexal lymphoma to antibiotics. Cancer. 2007;110(4):809–15.

Kim TM, Kim KH, Lee MJ, Jeon YK, Lee SH, Kim DW, et al. First-line therapy with doxycycline in ocular adnexal mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma: a retrospective analysis of clinical predictors. Cancer Sci. 2010;101(5):1199–203.

Kussick SJ, Kalnoski M, Braziel RM, Wood BL. Prominent clonal B-cell populations identified by flow cytometry in histologically reactive lymphoid proliferations. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;121(4):464–72.

Hara Y, Nakamura N, Kuze T, Hashimoto Y, Sasaki Y, Shirakawa A, et al. Immunoglobulin heavy chain gene analysis of ocular adnexal extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42(11):2450–7.

McKelvie PA, McNab A, Francis IC, Fox R, O'Day J. Ocular adnexal lymphoproliferative disease: a series of 73 cases. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2001;29(6):387–93.

Andrew NH, Coupland SE, Pirbhai A, Selva D. Lymphoid hyperplasia of the orbit and ocular adnexa: a clinical pathologic review. Surv Ophthalmol. 2016;61(6):778–90.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Konstantina Fragkia-Tsivou for providing the histopathology images.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

OK, GK, VG and SP analyzed and interpreted the patient data. OK, GK and SP wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Klavdianou, O., Kondylis, G., Georgopoulos, V. et al. Bilateral benign reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of the conjunctiva: a case treated with oral doxycycline and review of the literature. Eye and Vis 6, 26 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40662-019-0151-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40662-019-0151-4