Abstract

We present the results of five experiments on F and Cl partitioning during hydrous mantle melting under conditions relevant to subduction zone magmatism (1.2–2.5 GPa, 1,180°C–1,430°C). For each experiment, we determined the F and Cl partition coefficients between lherzolitic mineral phases (olivine, orthopyroxene (opx), clinopyroxene (cpx), and garnet), amphibole, and hydrous basaltic melts (0.2–5.9 wt.% dissolved H2O). At constant pressure, show contrasting response to the combined effects of decreasing temperature from 1,310°C to 1,180°C and increasing H2O content in the melt from 0.2 to 5.9 wt.%: . decreases from 0.123 ± 0.004 to 0.021 ± 0.014 while increases from 0.0021 ± 0.0031 to 0.07 ± 0.01. Similar results are observed for clinopyroxene: decreases from 0.153 ± 0.004 to 0.083 ± 0.004 while increases from 0.009 ± 0.0005 to 0.015 ± 0.0008. Experimentally determined F and Cl partition coefficients were used in a hydrous melting model of a lherzolitic mantle metasomatized by slab fluid. In this model, we vary the amount of metasomatic slab fluid added into the mantle while its composition is kept constant. Increasing the amount of fluid results in an increase of both the degree of melting (due to the effect of H2O addition) and the F and Cl input in the mantle wedge. Because of the change of F and Cl partition coefficients with the increase of H2O, the observed variation in the F and Cl contents of the modeled melts is produced not only by F and Cl input from the fluid, but also by the changes in F and Cl fractionation during hydrous melting. Overall, the model predicts that the Cl/F ratio of modeled melts increases with increasing fluid fraction. Therefore, a variation in the amount of fluid added to the mantle wedge can contribute to the variability in Cl/F ratios observed in arc melt inclusions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Volatile species (H2O, CO2, S, Cl, and F) recycling in subduction zones is the main driver of mantle wedge melting and production of arc magmas. Previous studies have shown that primitive arc magmas recorded in olivine-hosted melt inclusions are enriched in volatiles, especially H2O, compared to mid-ocean ridge basalts and/or their melt inclusions (e.g. Hilton et al. [2002], Straub and Layne [2003]; Wallace [2005]). The addition of volatiles in the mantle wedge,via H2O-rich fluids and/or melts derived from the downgoing slab facilitates partial melting in the mantle wedge by lowering the solidus temperature of mantle peridotites (e.g. Kushiro et al. [1968]; Kushiro [1969]; [1972]; [1990]; Mysen and Boettcher [1975]; Gaetani et al. [1994]) and affects the physical and chemical properties of arc magmas (e.g. Shaw [1963]; [1972]; Green [1973]; Mysen [1977]; Sisson and Grove [1993]; Ochs and Lange [1999]; Bercovici and Karato [2003]; Hirschmann [2006]). The composition of the metasomatized mantle wedge can vary greatly according to the nature (aqueous fluids formed from by the dehydration of the slab, or silicate melts, formed by the melting of the slab) and the amounts of slab-derived components added to the mantle (e.g. Ayers [1998]; Grove et al. [2002]; Rüpke et al. [2002]; Straub et al. [2004]). As the slab-derived components are still largely unconstrained, quantifying the volatile input from the slab remains a challenge.

Along with H2O, halogen elements such as F and Cl are also released from the slab and are enriched in the mantle wedge (Métrich et al. [1999]; Straub and Layne [2003]). In contrast to H2O and other volatile species, F and Cl are not significantly degassed from mafic magmas at the depth of melt inclusion formation, if at all (Carroll and Webster [1994]; Métrich and Wallace [2008]), because of their comparatively high solubility and low concentration in mafic magmatic liquid (Webster [2004]; Dalou et al. [2014]). Moreover, olivine-hosted melt inclusion studies have shown that F and Cl, unlike H2O, are less affected by post-entrapment diffusion through the host mineral (e.g. Gaetani et al. [2012]; Bucholz et al. [2013]; Lloyd et al. [2013]; Le Voyer et al. [2014]). Therefore, the F and Cl contents recorded by arc melt inclusions represent the product of fractional crystallization from primary melts, and thus they retain valuable information on the source composition of arc magmas.

Existing F and Cl data from basaltic melt inclusions recovered from subduction zone settings (e.g. Straub and Layne [2003]; Wallace [2005]; Le Voyer et al. [2008]; [2010]; Bouvier et al. [2008]; [2010]; Sadofsky et al. [2008]; Rose-Koga et al. [2012]) has revealed a high variability of F and Cl signatures (presented as Cl/F ratio in this paper) among volcanic arcs (Cl/F from approximately 0.5 to 10), but also from a single volcano (Cl/F from 1.1 to 4.1 for Shasta melt inclusions, Le Voyer et al. [2010]). One possible explanation for the Cl/F variability in arc melt inclusions is that the addition of an H2O-rich component derived from slab dehydration into the mantle wedge generates arc basalts with high Cl/F, while the addition of slab melts generates basalts with low Cl/F (Straub and Layne [2003]; Le Voyer et al. [2010]). This hypothesis is consistent with experimental data on F and Cl partitioning between minerals and aqueous fluids, which have shown that addition of an aqueous fluid to the mantle wedge efficiently enriches its Cl content but not its F content (Bernini et al. [2012]; Wu and Koga [2013]). Instead, it is suggested that F enrichment is most likely achieved by the percolation of silicate melts (Wu and Koga [2013]). Experimentally determined F partition coefficients between mantle minerals (olivine, pyroxenes, and garnet) and anhydrous silicate melts (Beyer et al. [2012]; Dalou et al. [2012]) allow the calculation of F content in melts produced by simple batch melting of an anhydrous lherzolite (with F =16 ppm, Saal et al. [2002]). The addition of those calculated anhydrous silicate melts (maximum F content approximately 400 ppm) into the mantle wedge does not generate high F content arc magmas (e.g. basaltic andesite melt inclusions from Cascades contain up to 1,220 ppm of F). In order to better assess the link between Cl/F signature and slab input, more experimental data on F and Cl partition coefficients under hydrous conditions, i.e. relevant to subduction zone magmatism, are needed. This is the objective of the present study. We address the effect of H2O on F and Cl partition coefficients between anhydrous minerals (olivine, orthopyroxene (opx), clinopyroxene (cpx), and garnet), amphibole, and hydrous basaltic melts (0.2–5.9 wt.% dissolved H2O), at mantle wedge conditions (1.2 and 2.5 GPa and 1,180°C and 1,430°C). It is shown that the strong and contrasting effect of H2O on F and Cl partitioning is key to the production of F-rich melts and to explain the variability of Cl/F ratios in mantle wedge products.

Methods

Starting materials

Three starting compositions (Table 1) were prepared as gel mixtures, following the procedure of Hamilton and Henderson ([1968]). The two basalts and the peridotite gels were made to be as close as possible in composition to the basalt-peridotite pair of Gaetani and Grove ([1998]) (basalt 82-72f and peridotite PUM), because a mixed 70:30 proportion of this basalt-peridotite pair allows to obtain liquidus saturation of mantle wedge phases (olivine, orthopyroxene, clinopyroxene, garnet/spinel), while maintaining large melt fractions in both anhydrous and hydrous systems (Gaetani and Grove [1998]). The hydrous basalt composition was prepared without Al2O3 to allow the introduction of H2O as gibbsite (Al(OH)3, Table 1). This protocol allows a better constraint on H2O content than the addition of a drop of liquid water for low H2O content samples. The gibbsite absorbs less atmospheric CO2 than brucite [Mg(OH)2, more commonly used for hydrous experiments, Béarat et al. [2002]. The gels were conditioned for 12 h at 800°C in a 1 atm gas-mixing furnace, with f O2 about 1 log unit above the quartz-fayalite-magnetite buffer (QFM). This f O2 was selected to mimic the oxidation state of sub-arc upper mantle (f O2 from 0.5 to 1.7 log units above QFM; Parkinson and Arculus [1999]).

Starting composition powders were dried for at least 12 h at 110°C to remove any H2O. Starting compositions were weighed to obtain a 70:30 proportion of basalt-peridotite and the desired H2O content by adjusting the proportion of H2O-bearing basalt versus H2O-free basalt. A drop of liquid water (approximately 1 μL) was also added in the H2O-rich samples (Table 2) to recover water lost by possible gibbsite destabilization occurring during arc welding. The F and Cl were weighted and added to the mixtures as MgF2 and MgCl2 to be in trace amounts (approximately 2,000 ppm each). Nevertheless, prior contaminations in F (from the capsules’ preparation, discussed in the ‘experimental procedure’ section) or Cl (from the powder storage in the oven containing NaCl cylinders) make the assessment of the initial F and Cl content difficult. Each mixture was then ground in an agate mortar with ethanol for 45 min. Finally, clinopyroxene seeds were added at the bottom of the sample capsules in experiments CD1 H0 and CD2H3 (Table 2) to catalyze cpx growth (Dalou et al. [2012]).

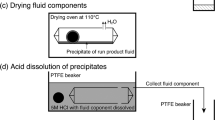

Experimental procedure

Experiments were conducted at 1.2 and 2.5 GPa and from 1,180°C to 1,430°C on ¾-inch and ½-inch piston cylinders at the Laboratoire Magmas et Volcans (LMV). Four- to six-day durations were chosen for experiments to optimize crystal size and to reach equilibrium (see results for more details on equilibrium considerations, Table 2). To reduce H2O and Fe losses from the starting material, Au80Pd20 double capsules, pre-saturated in Fe, were used. Moreover, because of the high H2O incompatibility in olivine (e.g. Hauri et al. [2006]), San Carlos olivines ground to approximately 10 μm were packed in the outer capsules (Figure 1). The pre-saturation in Fe consists of melting the starting basalt in those capsules, at the hotspot of a vertical gas-mixing furnace at 1,250°C, with f O2 controlled at 1 log unit below the FMQ buffer, for 72 h. The pre-saturation f O2 was chosen to be lower than the starting material f O2, since the basalt used for Fe pre-saturation was the unreduced starting gel and a pre-saturation at higher f O2, being more efficient (Ratajeski and Sisson [1999]), may have caused a Fe increase in samples. After the pre-saturation, the capsules were placed in an HF bath for 48 h at 90°C, followed by three ultrasound baths in distilled water of 1 h each. The capsules were then cleaned in a HNO3 − at 60°C to dissolve SiF precipitates and finally rinsed with distilled water. This procedure allowed the perfect dissolution of basaltic melt, but revealed that F contaminated the metallic capsules (up to several percent for samples CD2H4, CD2H5, and CD2H6, Table 3). However, this contamination does not significantly affect the determination of F and Cl partition coefficients (see ‘Results’ and ‘Discussion’ sections for more details). The pre-saturation procedure minimizes Fe loss from samples (<1.5 wt.%) but sometimes leads to an apparent Fe contamination from the capsule to the sample (Fe contamination up to 1.8 wt.%, Table 2). Overall, this Fe enrichment remains minimal compared to the Fe loss for experiments without pre-saturation (e.g. up to 4 wt.% and 2.9 wt.% average of Fe loss for similar conditions, Kawamoto and Hirose [1994]).

Back-scattered electron images of sample CD2H3 (A), (B). The rectangle zone in A enlarged to show coexisting minerals and interstitial melt in light gray, and (C) the rectangle zone in B enlarged to show cpx rims around small opx. Abbreviations used: Ol olivine, Opx orthopyroxene, Cpx clinopyroxene, and Melt quenched melt. The white part is the metal capsule noted as Fe-AuPd, i.e. AuPd pre-saturated in Fe. In the outer capsule, recrystallized olivine is visible. Mineral grains have >30-μm diameter, which is appropriate for SIMS measurements. The smallest opx has quench growth cpx around them (C). For analysis, we only used the largest opx (>50 μm) showing no cpx rims around them. Dendritic textures are observed as a boundary layer between crystallized areas and the melt pool. Except for this dendritic boundary, the melt is perfectly quenched.

A negligible water loss from the inner capsule to the surrounding olivine was measured by ion probe in sample CD2H3 (238 ± 1 ppm H2O loss, compared with the 2.6 wt.% dissolved in the melt). We also checked potential CO2 contamination by Fourier transform infrared analysis (LMV) of sample CD2H5. Less than 100 ppm of CO2 was measured in the melt.

Analytical procedure

Major element concentrations (given in Table 3) were analyzed by a Cameca SX100, LMV electron microprobe. Minerals were analyzed with a focused beam and a 15 nA current, whereas melts were analyzed by using a 8 nA current and a beam defocused to 5–20-μm diameter. The calibration standards, counting times, and choices of spectrometers are described in Hammouda ([2003]).

The abundance of F, Cl, and H2O (given in Table 3) was determined at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) with a Cameca IMF 1,280 ion probe following the procedure described in Rose-Koga et al. ([2008]), Shimizu et al. ([2009]), and Dalou et al. ([2012]). A Cs + primary ion beam rastered over an area of 30 × 30 μm2 was used. The primary beam intensity was approximately 1.43 nA during crystal analyses and decreased to 520 pA for melts. The beam size was between 20 × 20 to 10 × 10 μm2, depending on the size of the phases. At those conditions, the detection limit is <5 ppm for F, <2 ppm for Cl, and <0.01 wt.% for H2O. To achieve reliable F and Cl concentration measurements: 1) three to ten spots were measured per phase, and 2) only data with stable signals (less than 20% signal variation during analysis) were selected and used to determine element abundances.

The total uncertainty, taking into account both the standard deviation over ten cycles of analyses (i.e. internal error) and the errors on the regression of the calibration line, was approximately 10% for all volatiles.

Results

The results of hydrous experiments are compared with anhydrous analog samples CC4#7b and C4p#25 kb from Dalou et al. ([2012]), synthesized at 1.2 and 2.5 GPa, respectively. To facilitate the comparison, we use the following notation: CD1, refers to renamed samples from Dalou et al. ([2012]); and CD2, refers to samples from this study (Table 2).

Textural description of experimental samples

Figure 1 shows back-scattered electron images (BSE) of sample CD2H3. Sample textures are appropriate for microanalysis since pools of homogeneous quenched melt are segregated from crystal grains. No bubbles were observed in basaltic glasses, suggesting that the maximum of H2O content added to the starting materials (approximately 6 wt.%) was less than that needed for water saturation in these melts at pressure and temperature conditions of this study’s experiments. Iron contents measured in capsules (between 0.2 and 0.5 wt.%) suggest a f O2 during the experiment varying from approximately QFM +0.4 to QFM +1, depending on the experiment [following the solution models of Barr and Grove ([2010]) and Balta et al. ([2011])].

The degree of crystallization in runs varies from 32% to 72% (Table 2). The grain sizes are sufficiently large (>30 μm) to determine concentration of volatiles except for cpx in sample CD2-2.5GPa (≤30 μm). The mineral assemblage (Table 2) varies between samples due to variable pressure and temperature (P-T) conditions and to the abundance of volatiles (H2O, F, and Cl). Olivine is present in sample CD2H3 only, as large euhedral crystals (>50-μm diameter). Orthopyroxene is present in all experiments, forming polyhedral grains of 10- to 50-μm diameter, whereas cpx forms polyhedral grains of 5- to 50-μm diameter. Clinopyroxene rims (approximately 5-μm wide), overgrown during quenching, are also observed around some small opx crystals (<20 μm, Figure 1C), which were not analyzed for F and Cl. Dendritic clinopyroxene is also observed at the boundary between crystallized and quenched melt (Figure 1b). Garnet (<30-μm diameter) forms at 2.5 GPa, and is evenly distributed within the capsules. Amphibole is crystallized only in cpx-free samples at temperatures (1,180°C and 1,200°C) higher than typical stability conditions (stable up to 950°C at 1 GPa, Eggler [1972]), forming large euhedral crystals (approximately 300 μm). This higher temperature is likely because F increases amphibole stability (Ferguson [1978]).

Equilibrium considerations

Several observations indicate that the experiments approached equilibrium after 4–5 days. These observations include 1) polygonal crystal shape suggesting equilibrium growth (Figure 1); 2) lack of detectable compositional zoning in crystals (>20 μm); and 3) lack of compositional heterogeneity of melt (based on small standard deviations of replicate analyses, Table 4). Major element compositions of minerals and melt, presented in Table 4, agree with previous data (samples B333, B305, B304, B330, and B329 of Gaetani and Grove [1998], synthetized at same pressure and similar temperatures and H2O contents) in which the attainment of equilibrium was demonstrated via a reversal experiment (B277, Gaetani and Grove [1998]). Only sample CD2H5 shows some compositional deviations from previous experimental results. Specifically, the melt is richer in SiO2 by 5 wt.%, compared with data from Gaetani and Grove ([1998]) at similar conditions.

The attainment of chemical equilibrium is further inferred by comparing the Fe-Mg exchange coefficient between olivine and melt, , with that of previously reported values from anhydrous experiment data (Roeder and Emslie, [1970]; Toplis, [2005]). In the olivine-bearing sample (H3V04), the value is 0.30 and the predicted value, from the Toplis ([2005]) model, is 0.29 (±0.03). In olivine-free experiments, the Fe-Mg exchange coefficients between opx (or cpx) and melt measured in some of the volatile-poor experiments (CD1 H0, CD2H3, and CD2-2.5GPa: 0.25–0.32 ± 0.01 for opx, and 0.29–0.39 ± 0.02 for cpx) are similar to those of Gaetani and Grove ([1998]; 0.30–0.34 for opx and 0.32–0.35 for cpx). In F-contaminated samples (approximately 12–15 wt.% F), Kd values are significantly higher than the Gaetani and Grove ([1998]) values (0.52 ± 0.004 for CD2H6 opx and 0.59 ± 0.01 for CD2H5 cpx). Filiberto et al. ([2012]) showed that the Kd values increase with increasing F content in the melt. They show that at 2.9 wt.% F in anhydrous basalt glass is 0.40. They suggest that F complexes with Mg in the melt and thus increases the silica activity of the melt, depresses the liquidus, and changes the composition of the crystallizing minerals. Finally, one sample (CD2H5) has a (0.18 ± 0.03) that is lower than that of Gaetani and Grove ([1998]). This may indicate that a significant portion of iron in the melt is Fe3+, most likely due to a loss of H during this experiment.

Finally, equilibrium is assessed by error-weighted mass-balance calculations (Albarède and Provost [1977]) of the major element abundances. It verifies the closure of the chemical system in our experiments. Within uncertainty, results of mass-balance calculations account for the mixing proportions of basalt and peridotite and volatile elements (F, Cl, and H2O). The square root of the sum of residual square calculations (√ΣR2) ranges between 0.1% and 1.58% (Table 2). The main portions of these residuals likely relate to unknown uncertainties in F, Cl, and H2O abundance in the starting materials, which explains why √ΣR2 is significant (>0.5%).

Minerals have balanced stoichiometry (examined with total cations), except for orthopyroxene in sample CD2H4 (total cations in M1 site ≤1.9, instead of 2) and clinopyroxene in sample CD2-2.5GPa (total cations in M1 site >1.5, generally <1.2). For this reason, F and Cl data in orthopyroxene in sample CD2H4 and clinopyroxene in sample CD2-2.5GPa will not be discussed any further.

Fluorine and chlorine contents are homogeneous in minerals and melt (Table 3), with standard deviations less than 5% relative for F and less than 12% for Cl in olivine, opx, cpx, and garnet. These variations are smaller than the internal precision of a typical analysis.

F and Cl partition coefficients for hydrous experiments

Table 5 reports F and Cl mineral/melt partition coefficients () In samples synthetized at 1.2 GPa and at about the same temperature (±60°C), decreases from 0.056 ± 0.003 to 0.021 ± 0.031 and decreases from 0.114 ± 0.002 to 0.08 3 ± 0.004 with increasing H2O content (from 2.6 to 5.9 wt.%), while increases from 0.020 ± 0.0006 to 0.069 ± 0.010 and increases from 0.011 ± 0.001 to 0.015 ± 0.008 (Figure 2). The Dmineral/melt can be compared between olivine, opx, and cpx in sample CD2H3, where all three phases are coexisting: Dcpx/melt > Dopx/melt > Dol/melt for both F and Cl, consistently with Hauri et al. ([2006]), Dalou et al. ([2012]), Beyer et al. ([2012]). The amphibole/melt partition coefficients for F and Cl are higher than for nominally anhydrous minerals (NAMs) (). The F partition coefficients between amphiboles (fluor-pargasitic hornblende) are lower than experimentally determined in basaltic system (0.9–1.2, Hauri et al. [2006]) at higher H2O content, than D F between K-richterite and melt (0.9–1.8, Edgar and Pizzolato [1995]) and than modeled by Giesting and Filiberto ([2014]) ranging from 4 to 13 (undersaturated conditions). The amphibole/melt partition coefficients for Cl are consistent with the range of determined by the Giesting and Filiberto ([2014]) model (approximately 0.08–3), undersaturated conditions). At 2.5 GPa and 1,340°C, is 0.046 ± 0.001 and is 0.006 ± 0.0005, smaller than (0.166 ± 0.002) and (0.087 ± 0.004). Note that are greater than for all NAMs, which is consistent with the results of Dalou et al. ([2012]) and Hauri et al. ([2006]).

Comparison of D F and D Cl variations. Comparison of DF (A) and DCl (B) variations with increasing H2O content dissolved in the melt, at 1.2 GPa, for nominally anhydrous minerals (NAMS): orthopyroxene (diamonds), clinopyroxene (circles), olivine (cross) and garnet (triangle). Samples CD1 from Dalou et al. ([2012]) are shown in grey, while samples of this study are shown in black. The two trends are linear regression on opx and cpx data.

The effect of H2O content on the partitioning of F and Cl can be observed by comparing hydrous data from this study with the experiments from Dalou et al. ([2012]) performed at similar but anhydrous conditions. For example, at 1.2 GPa, Dopx/melt and Dcpx/melt can be compared with CD1 H0 of Dalou et al. ([2012]), also performed at 1.2 GPa (0.123 ± 0.004 versus 0.153 ± 0.004 for F, 0.002 ± 0.001 versus 0.009 ± 0.0005 for Cl, respectively, Table 5). Moreover, values in anhydrous and hydrous samples (0.123 ± 0.004–0.021 ± 0.031 at 1.2 GPa; 0.016 ± 0.001–0.046 ± 0.001 at 2.5 GPa) are in overall agreement with Beyer et al. ([2012]; 0.031 ±0.005 at 1 GPa, 0.037 ±0.001 at 2.5 GPa) who conducted anhydrous experiments in the CaO-MgO-Al2O3-SiO2 system. For F, the D opx/melt (Beyer et al. [2012]; Dalou et al. [2012]) and D cpx/melt (O’Leary et al. [2010]: 0.087 ± 0.004; Dalou et al. [2012]) of dry experiments are lower that the ones in hydrous experiments (O’Leary et al. [2010]: 0.051 ± 0.001–0.069 ± 0.001; this study); the is higher in the case of Cl (Hauri et al. [2006]; Dalou et al., [2012]; this study). This difference is consistent with the contrasting effect of increasing water content on the mineral/melt partitioning of F and Cl described above. The value (0.116) of Dalou et al. ([2012]) was dismissed because it is two orders of magnitude higher than that reported by Beyer et al. ([2012]) at similar P-T conditions in the CMASF (CaO, MgO, Al2O3, SiO2, and F) and NCMASF (Na2O, CaO, MgO, Al2O3, SiO2, and F) systems and by Hauri et al. ([2006]) in basaltic and basanitic systems. The discrepancy between these data is perhaps due to the presence of micro-inclusions, clinohumite lamellae, or clumped OH/F defects (Crépisson et al. [2014]) in the high F olivine (Dalou et al. [2012]). Thus, in the rest of the discussion, we used the average from Hauri et al. ([2006]), of 0.0026 ± 0.0001 and 0.0003 ± 0.0001, respectively. These averages are in a very good agreement with our data in the hydrous sample CD2H3: . Although the error on is significant, we decide to use this value because to date, no other values are available, except for maximum values given by Hauri et al. ([2006]; ranging from 0.002 to 0.003). For garnet, the (0.166 ± 0.002) and (0.087 ± 0.004) of hydrous sample CD2-2.5GPa is higher than (0.012 ± 0.0004) and (0.003 ± 0.0001) of anhydrous sample CD1-2.5GPa (2.5 GPa, Dalou et al. [2012], which is the only dry sample for which F and Cl partition coefficients were determined for garnet).

Discussion

Bulk F and Cl partitioning during hydrous melting

We calculated the bulk and ( see Table 6) between an anhydrous spinel lherzolite containing 57% olivine, 28% opx, 13% cpx, and 2% spinel; (Workman and Hart [2005]), and 1) anhydrous or 2) hydrous basaltic melt. These D values are 0.056 ± 0.002 for F and 0.0019 ± 0.0004 for Cl in the case of anhydrous melting and 0.018 ± 0.009 for F and 0.023 ± 0.005 for Cl in for hydrous melting, with 5.9 wt.% of H2O dissolved in the melt. Thus, from anhydrous to hydrous lherzolite melting, F becomes more incompatible (from 0.056 to 0.018) and Cl less incompatible (from 0.002 to 0.023). These results indicate that behavior of F and Cl become decoupled during hydrous melting. In the case of amphibole-bearing lherzolite (60% olivine, 20% opx, 15% cpx, and 5% amphibole), modeled bulk and () between amphibole-bearing lherzolite and hydrous basaltic melt are 0.048 ± 0.004–0.050 ± 0.011 and 0.013 ± 0.005–0.037 ± 0.009, respectively with increasing H2O content (from 4.3 to 5.9 wt.%). Nevertheless, in the melting model presented below, we used an amphibole-bearing wehrlite (Médard et al. [2006]), because to date no melting modes are available for amphibole-bearing lherzolite. In the case of amphibole-bearing wehrlite (20% olivine, 28% cpx, and 52% amphibole; Médard et al. [2006]), the high proportion of amphibole enhances its role during melting; modeled bulk and () used in the hydrous melting model are 0.219 ± 0.0002–0.353 ± 0.0003 and 0.066 ± 0.023–0.201 ± 0.043, respectively with increasing H2O content (from 4.3 to 5.9 wt.%).

Effect of melt structure on F and Cl partition coefficients

It is not possible to completely separate the effects of temperature and H2O on the F and Cl partition coefficients (Figure 2) because in order to obtain multi-phase assemblages in the experiments, it is necessary to decrease the temperature as the H2O content of the system is increased, to account for the effect of water on the solidus temperature of the peridotite phase assemblage (e.g. Kushiro [1969]). Moreover, we found no clear relationship between or and the F content dissolved in melts (Table 3), which supports the conclusion that the fluorine contamination from HF capsule cleaning (up to several weight percent, Table 3) cannot explain the F and Cl partition coefficient variations among the samples. The contrasting changes of F and Cl partition coefficients between pyroxenes and melt with increasing water content (i.e. decreasing temperature) is, therefore, the result of either 1) the effect of H2O and temperature on melting phase relations and phase composition, 2) their effect on the melt structure, or 3) a combination of both.

Figure 3 presents (A) and (B) versus the melt structure parameter NBO/T, which describes the number of non-bridging oxygen (NBO) per tetrahedrally coordinated cations (T). Here, a variation of NBO/T can result from the depolymerizing effect of H2O content (e.g. Mysen, [2007]) and F content (e.g. Mysen et al. [2004]), especially in F-rich samples. Because F depolymerizes melts equally or more efficiently than H2O (Dingwell and Virgo [1987]; Mysen et al. [2004]) the NBO/T data presented in Figure 3 were corrected for F content, assuming that F has the same depolymerizing effect as H2O (Mysen [2007]). The NBO/T values, before correction, were calculated following Mysen and Richet ([2005]; Chapter 4): NBO/T = (4•XT −2•XO)/XT, where XT and XO are the atomic proportions of tetrahedrally coordinated cations (Si and Al) and oxygen, respectively. A simple way to correct for the F effect is to assume that F has the same depolymerizing effect as H2O in aluminosilicate melts:

Mineral/melt partition coefficients of fluorine (A) and chlorine (B) versus NBO/T, (C) versus NBO/T and (D). versus NBO/T, where R is the gas constant and T the temperature in K. Here is equal to ∆G, the free Gibbs energy; NBO/T were calculated following the procedure in Mysen and Richet ([2005], Chapter 4) as explained in the text. Data from this study are compared with literature data for olivine (Hauri et al. [2006]; Beyer et al. [2012]), orthopyroxene (Hauri et al. [2006]; Beyer et al. [2012]; Dalou et al. [2012]), and clinopyroxene (Hauri et al. [2006]; O’Leary et al. [2010]; Dalou et al. [2012]).

where m is the slope value of NBO/T versus H2O (mol fraction) from Mysen ([2007]; for NS4NA7.5 composition, similar NBO/T and similar Al2O3 content as our basaltic melts), and [F] is the F mol fraction of each sample. This correction allows deciphering the effect of H2O from the effect of F on NBO/T in Figure 3.

Figure 3A,C shows that, for each mineral (from the literature data and this study), F partition coefficients tend to decrease with increasing H2O-induced NBO/T variations, i.e. with increasing melt depolymerization. In contrast, there is no obvious correlation between Cl partition coefficients for pyroxenes and NBO/T (Figure 3B,D). We interpret that the scattering of D Cl versus NBO/T reflects the fact that mineral chemistry has a significant role in D Cl variation, as suggested by Bernini et al. ([2012]) and Dalou et al. ([2012]). For example, a mild correlation between Cl substitution and octahedral site elasticity has been demonstrated by Dalou et al. ([2012]). In contrast, Dalou et al. ([2012]) found no direct correlation between D F and pyroxene chemistry or elastic parameters. Fluorine, being smaller than Cl (133 and 181 pm, respectively), is more sensitive to melt structure than Cl (Dalou et al. [2012]). The same relationship between ion size and melt depolymerization was previously found for cations (e.g. Gaetani et al. [2003]).

Previous work on F and Cl solution behavior in aluminosilicate melts (Mysen and Virgo [1985]; Kohn et al. [1991]; Schaller et al. [1992]; Zeng and Stebbins [2000]; Mysen et al. [2004]; Zimova and Webb [2006]; Baasner et al. [2013]) have shown that F preferentially bonds with tetrahedrally coordinated cations such as Al and Si. Although in more complex melts such as basalt, F can also preferentially bond with Mg (Kiczenski et al. [2004]; Filiberto et al. [2012]) and form more complex bonds as Al-F-Ca or Al-F-Na (Zeng and Stebbins [2000]; Mysen et al., [2004]); Si-F and Al-F are always found. Moreover, as NBO/T increases, F bonding and dissolution in silicate melts is favored (Mysen et al. [2004]). In contrast, Cl preferentially bonds with network-modifier cations (Ca, Na, K; Stebbins and Du [2002]; Sandland et al. [2004]; Zimova and Webb [2006]; Dalou and Mysen [2012]; Baasner et al. [2013]) or with Fe2+ in F-rich basalt (Filiberto and Treiman [2009]; Filiberto et al. [2014]), and its solubility in aluminosilicate melts decreases with increasing NBO/T (Dalou and Mysen [2012]). Assuming that F and Cl solubility response to NBO/T in compositionally simple aluminosilicate melts can be extended to basaltic composition, F and Cl solubility response to NBO/T can explain changes of F incompatibility and partly Cl incompatibility. As shown above, the variation of melt structure in our experiments is mainly due to the variation in dissolved H2O content. Therefore, the variation in H2O content dissolved in melts is the main cause of our F partition coefficient variation and also could have a role of the Cl partition coefficient variation. This is consistent with recent F and Cl solubility results in aluminosilicate melts with increasing H2O content (Dalou and Mysen [2013]) where increasing H2O content in the melt results in increased F. This means that mineral/melt partition coefficients decrease with increasing H2O and results, therefore, in decreased mineral/melt partition coefficients for chlorine.

F and Cl during hydrous melting

Fluid-induced melting model

The and were used to calculate the F and Cl composition of melts derived from a spinel lherzolite (57% olivine, 28% opx, 13% cpx, and 2% spinel; Workman and Hart [2005]) metasomatized by various proportions of aqueous fluids. In this model, we assume that the partial melts are undersaturated in aqueous fluids because our experiments are undersaturated in H2O. Therefore, the model follows the flux-induced melting proposed by Stolper and Newman ([1994]) and Eiler et al. ([2000]). The equation chosen is derived from Eiler et al. ([2000]) modified to represent non-modal melting following the equation by Johnson et al. ([1990]) (Table 6).

In this equation, i stands for F or Cl. The partition coefficients of element i at χ degree of melting, are the mineral proportion weighted partition coefficients of i. are the weighted partition coefficients of liquid. The X f represents the amount of metasomatic fluid added to the lherzolite. From the fluid-induced melting model (Stolper and Newman [1994]; Eiler et al. [2000]), it is assumed that the fluid is the main factor controlling the degree of melting at constant pressure and temperature. For example, every addition of 1 wt.% H2O results in 10 wt.% of partial melting (Eiler et al. [2000]). This notion is introduced by the factor alpha (α), the rate of fluid-induced melting, expressed as α = amount of H2O added to the lherzolite divided by the degree of melting. In equation (2), X f is replaced by to obtain equation (3). The term takes into account that 1) the degree of melting x depends on the amount of H2O added by the slab flux, and 2) the slab fluid composition is not pure H2O. Thus, we normalized X f to the amount of H2O in slab fluxes :

In this study, alpha (α) values were chosen to be 0.026, 0.049, 0.059, and 0.10, because α corresponds to the H2O content dissolved in melts during the experiments (2.6, 4.9, and 5.9 wt.%, Table 6). Although no experiment was performed with 10 wt.% H2O dissolved in the melt, α = 0.10 was chosen to test the model reaction to a high rate of fluid-induced melting. The is calculated from stoichiometric coefficients for spinel lherzolite melting reactions under anhydrous and hydrous conditions using Kinzler ([1997]) and Gaetani and Grove ([1998]), respectively. For amphibole-bearing lithology, the stoichiometric coefficients of an amphibole-bearing wehrlite from Médard et al. ([2006]) were chosen. In the melting calculation, the degree of melting, χ, of the metasomatized lherzolite was varied from 1% to 20%. The composition of the anhydrous lherzolite is the depleted upper mantle composition (F = 16 ppm and Cl = 0.83 ppm) from Saal et al. ([2002]). Three different compositions of slab components, , were tested. Two different aqueous fluids: F = 990 ± 270 ppm, Cl = 9,390 ± 2,500 ppm, and H2O = 25 ± 7 wt.% from Straub and Layne ([2003]) and F = 2,200 ppm, Cl = 8,900 ppm, and H2O = 53 wt.% from Le Voyer et al. ([2010]) were used; together with one slab derived melt: F = 13,700 ppm, Cl = 14,800 ppm, and H2O = 44.5 wt.% from Le Voyer et al. ([2010]) (Figure 4).

Modeled melt Cl/F ratios are shown as a function of degrees of fluid induced melting. Model tests three slab components (stars): slab fluid composition from Straub and Layne ([2003]) (black star), slab fluid composition from Le Voyer et al. ([2010]) (grey star), and slab melt composition from Le Voyer et al. ([2010]) (white star). Lines exhibit the variation of the rate of fluid-induced melting, by changing α values: 0.026 (dashed lines), 0.049 (dotted lines), and 0.059 (solid lines). Crosses are calculated points from the model joined by the lines for more clarity. The black diamond shows the depleted mantle composition. The grey rectangle on the side of the diagram shows the range of Cl/F in arc melt inclusions (Straub and Layne [2003]; Elburg et al. [2006]; Wysoczanski et al. [2006]; Churikova et al. [2007]; Portnyagin et al. [2007]; Sadofsky et al. [2008]; Vigouroux et al. [2008]; Bouvier et al. [2008]; [2010]; Le Voyer et al. [2008]; [2010]; Sorbadere et al. [2011]; Shaw et al. [2012]; Rose-Koga et al. [2012]). The Cl/F ratio is determined by the slab component, the degree of melting, but also the rate of fluid-induced melting. In other words, it means that the amount of fluid component has an influence of the Cl/F ratio in melts. Interestingly, at low degrees of slab fluid-induced melting (1% to 10%), Cl/F ratios in melts are higher for α = 0.049 than for α = 0.059. This is because Cl content in the melt is controlled by increasing incompatibility in opx and the dissolution of opx with increasing α.

This simple model illustrates how an increase in the proportion of metasomatic fluid affects magma composition in two ways: (1) the degree of melting increases; and (2) more metasomatic component (mostly H2O and Cl) resides in the final magma. In other words, the model illustrates the competition between fractionation and dilution of F and Cl. Note that this model calculation is aimed to assess the role of variable F and Cl partition coefficients in wet and dry mantle, in order to extract robust systematics. It emphasizes the basic framework of the fluid-induced melting, but ignores potential complication of arc magma genesis such as reactive fluid and melt transport, super-adiabatic and adiabatic melting.

With increasing degree of melting, χ, the Cl/F ratio in the final melt increases independently of the composition of the slab fluid (Figure 4). This ratio also increases with increasingly Cl-rich metasomatic fluids. Therefore, both the fluid composition and degree of melting are the major variables controlling the melt Cl/F values. The increasing degree of melting has more effect on the Cl/F ratio than α, the rate of fluid-induced melting (Figure 4). For example, at constant degree of melting (20%), the Cl/F ratio of melts increases by a factor of 1.3 (from 5.2 to 6.7) as the melt H2O content varies from 2.6 to 5.9 wt.%. In comparison, for α = 0.059, Cl/F increases by factor of 6.4 (from 1.0 to 6.7) from 1% to 20% degree of melting.

Comparisons to F and Cl in arc melt inclusions

Figure 5A reports F and Cl concentrations in melt inclusions from various volcanic arcs (grouped in arcs: Trans-Mexican: Sadofsky et al. [2008]; Vigouroux et al. [2008]; Kamchatka: Churikova et al. [2007]; Portnyagin et al. [2007]; Kermadec: Wysoczanski et al. [2006]; Izu-Mariana: Straub and Layne [2003]; Shaw et al. [2012]; Sunda: Elburg et al. [2006]; Aeolian: Rose-Koga et al. [2012]; Cascade: Le Voyer et al. [2010]; S. America: Le Voyer et al. [2008]; Vanuatu: Sorbadere et al. [2011]; Lesser Antilles: Bouvier et al. [2008]; [2010]) and illustrates the variety of Cl/F ratios among arc magmas (between 0.25 and 10). Although the variations of degree of melting and crystallization are likely responsible for some of F and Cl variation within each group of arc melt inclusions, it is unlikely that crystallization is solely responsible for these variations. For instance, Le Voyer et al. ([2010]) investigated the variation of volatile elements signature among Mount Shasta melt inclusions, by minimizing the effect of melting-crystallization normalizing F and Cl content to Y content (incompatible, fluid-immobile element). It appears that Mount Shasta melt inclusions display two trends of Cl/Y versus F/Y that corresponds to two distinct Cl/F ratios of approximately 1 and 4. Therefore, although some of the variation observed on Figure 5A might be produced by variable degree of crystallization of different samples, it is likely that a large part of the Cl/F variations is related to the magma genesis in the mantle wedge.

Cl versus F in, (A) arc melt inclusions, slab and mantle wedge, (B, C, and D) predicted melts. (A) Melt inclusions data are compiled from recent studies (see text). Each thin line represents a constant Cl/F ratio. (B) Melt compositions derived from anhydrous mantle (DMM, blue diamond) are predicted by the dark gray curve. Predicted melts’ compositions calculated for fluid-induced melting of a spinel lherzolite are indicated by the dotted curve for low degree (α = 0.026), dashed for intermediate (α = 0.049), and solid curves for high (α = 0.059) and very high degree of melt production rate for a unit flux (α = 0.1). Fluid composition is from Straub and Layne ([2003]) (black star). Fluid-induced melting of an amphibole-bearing wehrlite is indicated by gray curves: dashed for α = 0.043 and dotted for α = 0.059. Each curve is graduated as a function of degree of melting (from 1% to 20%). See text for details on the model parameters. The gray line represents the mixing line between the fluid composition (Straub and Layne, [2003]) and the DMM. Compositions of aqueous fluid from Le Voyer et al. ([2010]) and slab melt from Le Voyer et al. ([2010]) are shown for comparison (gray star and white star, respectively). (C) F and Cl compositions of melts produced by fluid-induced melting of a lherzolite metasomatized by an aqueous fluid from Le Voyer et al. ([2010]). (D) F and Cl compositions of melts produced by fluid-induced melting of a lherzolite metasomatized by slab-derived melt from Le Voyer et al. ([2010]).

The variations in volatile and trace elements composition are commonly explained by a compositional variation of the metasomatic agent (e.g. Straub et al. [2004]; Le Voyer et al. [2008]; Sadofsky et al. [2008]; Bouvier et al. [2010]; Sorbadere et al. [2011]). The composition of the metasomatic agent is usually calculated from mass balance assuming a mixing between the depleted mantle (DMM) and this agent, either a slab aqueous fluid or a slab melt (e.g. Grove et al. [2002]; Straub and Layne [2003]; Straub et al. [2004]; Le Voyer et al. [2010]). Considering that seawater is about 20,000 times richer in Cl than F (e.g. Straub and Layne [2003]) and that Cl is highly soluble in slab aqueous fluids (e.g. Brenan [1993]), a Cl/F >1 in arc melt inclusions is expected. The Cl/F ratio in aqueous fluid from slab dehydration was estimated to be approximately 4 (e.g. Mount Shasta, Le Voyer et al. [2010]) or up to 9.5 (e.g. Izu arc front, Straub and Layne [2003]). In contrast, the low Cl/F (<1) found in some arc melt inclusions (e.g. Central and South American arcs, Kermadec, Wysoczanski et al. [2006]; Sadofsky et al. [2008]; Vigouroux et al. [2008]; Mount Shasta, Le Voyer et al. [2010]) cannot result from the mixing between a depleted source and an aqueous fluid. Instead, it was suggested that it was produced by mixing with a H2O-rich slab melt (e.g. Le Voyer et al. [2010]), with a Cl/F approximately 1 (Figure 5B).

Part of the Cl/F variability in arc melt inclusions could also result from the presence of hydrous minerals as amphiboles or micas, such as pargasite or phlogopite. On Figure 5B, melting trends of an amphibole-bearing wehrlite are reported. This trend is almost parallel to the mixing trend between DMM and fluid and shows that Cl is more fractionated than F during amphibole-bearing wehrlite melting. Melt inclusions from the western Trans-Mexican arc display very low Cl/F (approximately 0.5), which has been interpreted as the melting of a phlogopite-bearing lithology (Vigouroux et al. [2008]). Although more experimentally determined partition coefficients of F and Cl are needed for amphibole and phlogopite, the melting of a mantle with hydrous phases likely would fractionate F and Cl differently than in an anhydrous mantle. The hydroxyl site of hydrous phases such as amphiboles and micas provide ideal substitution sites for F and Cl, therefore and should be higher than the ones of NAMs. Thus, we suggest that F and Cl fractionation during the melting of amphibole or mica-bearing lithologies may explain some of Cl/F variability in melt inclusions.

The effect of H2O on and implies that the F and Cl signature in melts is somehow related to the amount of aqueous fluid involved during arc magma genesis. When model results shown in Figure 4, tested for fluid composition from Straub and Layne ([2003]), are plotted in the Cl versus F diagram (Figure 5B), the direction of melting trends is determined by the value of α, whereas the extent of the trends are determined by the degree of melting. There is a rotation in the F versus Cl melting trends with the increasing proportion of metasomatic fluids: from a negative slope of Cl versus F at low α to a near-vertical slope at α = 0.1. At low α, the fluid input, and in particular the Cl input from the fluid, is low. Therefore, the melting trend is determined by and . As α increases, there is competition between the F and Cl fractionation (controlled by and ) and the dilution of Cl carried by the fluid. This is why Cl begins to fractionate more than F as α increases and why at very high α, only Cl seems to fractionate. This change of melting trend directions suggest that various Cl/F ratios in melts can be produced by variable rate of fluid-induced melting without changing the composition of the fluid. Interestingly, subvertical alignments of melt inclusion compositions are seen among the Lesser Antilles, Aeolian, and Vanuatu arcs and some of the Cascade arc (Figure 5A). While high α melting trend and data trends may not be an exact match, it is possible that these subvertical alignments result from melting at high fluid content, with a strong fractionation of Cl compared to F. This suggests that (1) the natural highly variable Cl trends we observe probably represent melting trends and (2) those magmas were produced by high degree of metasomatism.

In modeled melts, consequently to increasing α, not only Cl increases because of increasing fluid input, but F increases as well because decreases with increasing H2O content. Note that the model described here does not challenge the important role of the metasomatic agent in the composition of arc magmas (Figure 5C,D). The nature of this agent, fluid or melt, and its composition also control the slope of melting trends (Figure 5B–D). At high degree of melting (>20%), the melt compositions are near that of melt in the mixing lines between the DMM and slab components. In summary, while the main variability of Cl/F ratio among melt inclusions is produced by the various composition of slab component, within the same arc region or the same volcano at a given time, some Cl/F variability can be explained by variable amount of the same slab component (which has also a strong influence on the degree of melting of the mantle wedge).

Conclusions

We report F and Cl partition coefficients between olivine, orthopyroxene, clinopyroxene, garnet and amphibole, and hydrous basaltic melt for P-T conditions ranging from 1.2 to 2.5 GPa and 1180 to 1430°C, with a H2O content dissolved in the melt ranging from 0.2 to 5.9 wt%. We show that increasing H2O content has a contrasting effect on F and Cl partition coefficients between anhydrous minerals and melt. The decrease with the increasing melt depolymerization resulting from increasing H2O content. In contrast, increase with melt H2O content. This relationship is complex since Cl behavior depends on both melt and crystal chemistry.

Because our experimental conditions are relevant to that of the mantle wedge, our and data were used to model Cl/F ratio in arc magmas produced by fluid induced melting. We establish that fluid induced melting can produce high Cl/F and high F content melts, even when the metasomatic agent is an aqueous fluid. Our model shows that the Cl/F variability in arc melt inclusions results from 3 related variables: the composition but also the amount of metasomatic agent released from the slab into the mantle wedge and the degree of melting induced by the amount of metasomatic agent.

References

Albarède F, Provost A: Petrological and geochemical mass-balance equations: an algorithm for least-square fitting and general error analysis. Comput Geosci 1977, 3: 309–326. 10.1016/0098-3004(77)90007-3

Ayers J: Trace element modeling of aqueous fluid–peridotite interaction in the mantle wedge of subduction zones. Contribut Mineral Petrol 1998,132(4):390–404. 10.1007/s004100050431

Baasner A, Schmidt BC, Webb SL (2013) Compositional dependence of the rheology of halogen (F, Cl) bearing-aluminosilicate melts. Chem Geol 346(C):172–183

Balta JB, Beckett JR, Asimow PD: Thermodynamic properties of alloys of gold-74/palladium-26 with variable amounts of iron and the use of Au-Pd-Fe alloys as containers for experimental petrology. Am Mineral 2011,96(10):1467–1474. 10.2138/am.2011.3637

Barr JA, Grove TL (2010) AuPdFe ternary solution model and applications to understanding the f O2 of hydrous, high-pressure experiments. Contrib Mineral Petrol 160(5):631–643

Béarat H, McKelvy MJ, Chizmeshya AV, Sharma R, Carpenter RW: Magnesium hydroxide dehydroxylation/carbonation reaction processes: implications for carbon dioxide mineral sequestration. J Am Ceramic Soc 2002,85(4):742–748. 10.1111/j.1151-2916.2002.tb00166.x

Bercovici D, Karato S: Whole mantle convection and the transition-zone water filter. Nature 2003, 425: 39–44. 10.1038/nature01918

Bernini D, Wiedenbeck M, Dolejš D, Keppler H: Partitioning of halogens between mantle minerals and aqueous fluids: implications for the fluid flow regime in subduction zones. Contrib Mineral Petrol 2012, 165: 117–128. 10.1007/s00410-012-0799-4

Beyer C, Klemme S, Wiedenbeck M, Stracke A, Vollmer C: Fluorine in nominally fluorine-free mantle minerals: experimental partitioning of F between olivine, orthopyroxene and silicate melts with implications for magmatic processes. Earth Planet Sci Lett 2012, 337–338: 1–9. 10.1016/j.epsl.2012.05.003

Bouvier A-S, Metrich N, Deloule E: Slab-derived fluids in the Magma Sources of St. Vincent (Lesser Antilles Arc): volatile and light element imprints. J Petrol 2008, 49: 1427–1448. 10.1093/petrology/egn031

Bouvier A-S, Metrich N, Deloule E: Light elements, volatiles, and stable isotopes in basaltic melt inclusions from Grenada, Lesser Antilles: inferences for magma genesis. Geochem Geophys Geosyst 2010., 11: 10.1029/2010GC003051

Brenan J: Partitioning of fluorine and chlorine between apatite and aqueous fluids at high pressure and temperature: implications for the F and Cl content of high P-T fluids. Earth PlanetSci Lett 1993, 117: 251–263. 10.1016/0012-821X(93)90131-R

Bucholz CE, Gaetani GA, Behn MD, Shimizu N: Post-entrapment modification of volatiles and oxygen fugacity in olivine-hosted melt inclusions. Earth PlanetSci Lett 2013, 374: 145–155. 10.1016/j.epsl.2013.05.033

Carroll MR, Webster JD: Solubilities of sulfur, noble gases, nitrogen, chlorine, and fluorine in magmas. Rev Mineral Geochem 1994,30(1):231–279.

Churikova T, Wörner G, Mironov N, Kronz A: Volatile (S, Cl and F) and fluid mobile trace element compositions in melt inclusions: implications for variable fluid sources across the Kamchatka arc. Contribut Mineral Petrol 2007, 154: 217–239. 10.1007/s00410-007-0190-z

Crépisson C, Blanchard M, Bureau H: Clumped fluoride-hydroxyl defects in forsterite: implications for the upper-mantle. Earth Planet Sci Lett 2014, 390: 287–295. 10.1016/j.epsl.2014.01.020

Dalou C, Mysen BO (2012) F and Cl solubility and solution mechanisms in aluminosilicate melts at high pressure and high temperature. Eos Trans AGU Fall Meet, Abstract MR11C −2509

Dalou C, Mysen BO (2013) The effect of water on fluorine and chlorine solubility and solution mechanisms in aluminosilicate melts at high pressure and high temperature. IAVCEI, abstract 1A1_1A-O18

Dalou C, Koga KT, Shimizu N, Boulon J, Devidal J-L: Experimental determination of F and Cl partitioning between lherzolite and basaltic melt. Contribut Mineral Petrol 2012, 163: 591–609. 10.1007/s00410-011-0688-2

Dalou C, Mysen BO, Foustoukos DI (2014) In-situ measurements of fluorine and chlorine speciation and partitioning between melts and aqueous fluids in the Na2O-Al2O3-SiO2-H2O system. Am Mineral, in press

Dingwell DB, Virgo D (1987) The effect of oxidation state on the viscosity of melts in the system Na2O-FeO-Fe2O3-SiO2. Geochimica Cosmochimica Acta 51:195–205

Edgar AD, Pizzolato LA: An experimental study of partitioning of fluorine between K-richterite, apatite, phlogopite, and melt at 20 kbar. Contribut Mineral Petrol 1995,121(3):247–257. 10.1007/BF02688240

Eggler DH (1972) Amphibole stability in H2O-undersaturated calc-alkaline melts. Earth Planet Sci Lett 15(1):28–34

Eiler JM, Schiano P, Kitchen N, Stolper EM: Oxygen-isotope evidence for recycled crust in the sources of mid-ocean-ridge basalts. Nature 2000,403(6769):530–534. 10.1038/35000553

Elburg M, Kamenetsky V, Nikogosian IK, Foden J, Sobolev AV: Coexisting high- and low-calcium melts identified by mineral and melt inclusion studies of a subduction-influenced syn-collisional magma from South Sulawesi, Indonesia. J Petrol 2006, 47: 2433. 10.1093/petrology/egl050

Ferguson AK: The crystallization of pyroxenes and amphiboles in some alkaline rocks and the presence of a pyroxene compositional gap. Contribut Mineral Petrol 1978,67(1):11–15. 10.1007/BF00371628

Filiberto J, Treiman AH: The effect of chlorine on the liquidus of basalt: first results and implications for basalt genesis on Mars and Earth. Chem Geol 2009,263(1):60–68. 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2008.08.025

Filiberto J, Wood J, Dasgupta R, Shimizu N, Le L, Treiman AH: Effect of fluorine on near-liquidus phase equilibria of a Fe–Mg rich basalt. Chem Geol 2012, 312–313: 118–126. 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2012.04.015

Filiberto J, Dasgupta R, Gross J, Treiman AH: Effect of chlorine on near-liquidus phase equilibria of an Fe–Mg-rich tholeiitic basalt. Contribut Mineral Petrol 2014,168(1):1–13. 10.1007/s00410-014-1027-1

Gaetani GA, Grove TL: The influence of water on melting of mantle peridotite. Contribut Mineral Petrol 1998, 131: 323–346. 10.1007/s004100050396

Gaetani GA, Grove TL, Bryan WB: Experimental phase relations of basaltic andesite from Hole 839b under hydrous and anhydrous conditions. In Proc ODP Sci Results. 135th edition. Edited by: Hawkins J, Parsons L, Allan J. Ocean Drilling Program, College Station TX; 1994:557–564.

Gaetani GA, Kent AJ, Grove TL, Hutcheon ID, Stolper EM: Mineral/melt partitioning of trace elements during hydrous peridotite partial melting. Contribut Mineral Petrol 2003,145(4):391–405. 10.1007/s00410-003-0447-0

Gaetani GA, O’Leary JA, Shimizu N, Bucholz CE, Newville M (2012) Rapid reequilibration of H2O and oxygen fugacity in olivine-hosted melt inclusions. Geology 40(10):915–918

Giesting PA, Filiberto J: Quantitative models linking igneous amphibole composition with magma Cl and OH content. Am Mineral 2014,99(4):852–865. 10.2138/am.2014.4623

Green DH: Experimental melting studies on a model upper mantle composition at high pressure under water-saturated and water-undersaturated conditions. Earth Planet Sci Lett 1973,19(1):37–53. 10.1016/0012-821X(73)90176-3

Grove T, Parman S, Bowring S, Price R, Baker M (2002) The role of an H2O-rich fluid component in the generation of primitive basaltic andesites and andesites from the Mt. Shasta region. N California Contribut Mineral Petrol 142(4):375–396

Hamilton DL, Henderson CMB: The preparation of silicate compositions by gelling method. Mineral Mag 1968, 36: 832–838. 10.1180/minmag.1968.036.282.11

Hammouda T: High-pressure melting of carbonated eclogite and experimental constraints on carbon recycling and storage in the mantle. Earth Planet Sci Lett 2003,214(1):357–368. 10.1016/S0012-821X(03)00361-3

Hauri E, Gaetani G, Green T (2006) Partitioning of water during melting of the Earth’s upper mantle at H2O-undersaturated conditions. Earth Planet Sci Lett 248:715–734

Hilton DR, Fischer TP, Marty B: Noble gases and volatile recycling at subduction zones. Rev Mineral Geochem 2002,47(1):319–370. 10.2138/rmg.2002.47.9

Hirschmann MM (2006) Water, melting, and the deep Earth H2O cycle. Annu Rev Earth Planet Sci 34:629–653 Hirschmann MM (2006) Water, melting, and the deep Earth H2O cycle. Annu Rev Earth Planet Sci 34:629–653

Johnson K, Dick HJB, Shimizu N: Melting in the oceanic upper mantle: an ion microprobe study of diopsides in abyssal peridotites. J Geophys Res 1990,95(B3):2661–2678. 10.1029/JB095iB03p02661

Kawamoto T, Hirose K: Au-Pd sample containers for melting experiments on iron and water bearing systems. Eur J Mineral Ohne Beihefte 1994,6(3):381–386. 10.1127/ejm/6/3/0381

Kiczenski TJ, Du LS, Stebbins JF: F-19 NMR study of the ordering of high field strength cations at fluoride sites in silicate and aluminosilicate glasses. J Non-Crystalline Solids 2004,337(2):142–149. 10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2004.03.123

Kinzler RJ: Melting of mantle peridotite at pressures approaching the spinel to garnet transition: Application to mid-ocean ridge basalt petrogenesis. J Geophys Res 1997,102(B1):853–874. 10.1029/96JB00988

Kohn SC, Dupree R, Mortuza MG, Henderson CMB: NMR evidence for five-and six-coordinated aluminum fluoride complexes in F-bearing aluminosilicate glasses. Am Mineral 1991,76(1–2):309–312.

Kushiro I: The system forsterite–diopside–silica with and without water at high pressures. Am J Sci 1969, 267A: 269–294.

Kushiro I: Effect of water on the composition of magmas formed at high pressures. J Petrol 1972,13(2):311–334. 10.1093/petrology/13.2.311

Kushiro I: Partial melting of mantle wedge and evolution of island arc crust. J Geophys Res 1990, 95: 15929–15939. 10.1029/JB095iB10p15929

Kushiro I, Yoder HS Jr, Nishikawa M: Effect of water on the melting of enstatite. Geologic Soc Am Bull 1968, 79: 1685–1692. 10.1130/0016-7606(1968)79[1685:EOWOTM]2.0.CO;2

Le Voyer M, Rose-Koga EF, Laubier M, Schiano P: Petrogenesis of arc lavas from the Rucu Pichincha and Pan de Azucar volcanoes (Ecuadorian arc): major, trace element, and boron isotope evidences from olivine-hosted melt inclusions. Geochem Geophys Geosyst 2008, 9: 1–27. 10.1029/2008GC002173

Le Voyer M, Rose-Koga EF, Shimizu N, Grove TL, Schiano P (2010) Two contrasting H2O-rich components in primary melt inclusions from Mount Shasta. J Petrol 51:1571–1595

Le Voyer M, Asimow PD, Mosenfelder JM, Guan Y, Wallace PJ, Schiano P, Stolper EM, Eiler JM (2014) NanoSIMS determination of H2O and F concentrations in olivines around melt inclusions. J Petrol, doi: 10.1093/petrology/egu003

Lloyd AS, Plank T, Ruprecht P, Hauri EH, Rose W: Volatile loss from melt inclusions in pyroclasts of differing sizes. Contribut Mineral Petrol 2013,165(1):129–153. 10.1007/s00410-012-0800-2

Médard E, Schmidt MW, Schiano P, Ottolini L: Melting of amphibole-bearing wehrlites: an experimental study on the origin of ultra-calcic nepheline-normative melts. J Petrol 2006,47(3):481–504. 10.1093/petrology/egi083

Métrich N, Wallace PJ: Volatile abundances in basaltic magmas and their degassing paths tracked by melt inclusions. Rev Mineral Geochem 2008,69(1):363–402. 10.2138/rmg.2008.69.10

Métrich N, Schiano P, Clocchiatti R, Maury RC: Transfer of sulfur in subduction settings: an example from Batan Island (Luzon volcanic arc, Philippines). Earth Planet Sci Lett 1999,167(1):1–14. 10.1016/S0012-821X(99)00009-6

Mysen BO (1977) The solubility of H2O and CO2 under predicted magma genesis conditions and some petrological and geophysical implications. Rev Geophys 15(3):351–361

Mysen BO (2007) The solution behavior of H2O in peralkaline aluminosilicate melts at high pressure with implications for properties of hydrous melts. Geochimica Cosmochimica Acta 71(7):1820–1834

Mysen BO, Boettcher AL: Melting of a hydrous mantle: I. Phase relations of natural peridotite at high pressures and temperatures with controlled activities of water, carbon dioxide, and hydrogen. J Petrol 1975,16(1):520–548. 10.1093/petrology/16.1.520

Mysen BO, Richet P: Silicate Glasses and Melts - Properties and Structure. Elsevier, New York; 2005.

Mysen BO, Virgo D (1985) Structure and properties of fluorine-bearing aluminosilicate melts: the system Na2O-Al2O3-SiO2-F at 1 atm. Contribut Mineral Petrol 91(3):205–220

Mysen BO, Cody GD, Smith A: Solubility mechanisms of fluorine in peralkaline and meta-aluminous silicate glasses and in melts to magmatic temperatures. Geochimica Cosmochimica Acta 2004,68(12):2745–2769. 10.1016/j.gca.2003.12.015

O’Leary JA, Gaetani GA, Hauri EH (2010) The effect of tetrahedral Al3+ on the partitioning of water between clinopyroxene and silicate melt. Earth Planet Sci Lett 297:111–120 O’Leary JA, Gaetani GA, Hauri EH (2010) The effect of tetrahedral Al3+ on the partitioning of water between clinopyroxene and silicate melt. Earth Planet Sci Lett 297:111–120

Ochs FA, Lange RA: The density of hydrous magmatic liquids. Science 1999, 283: 1314–1317. 10.1126/science.283.5406.1314

Parkinson IJ, Arculus RJ: The redox state of subduction zones: insights from arc-peridotites. Chemical Geology 1999, 160: 409–423. 10.1016/S0009-2541(99)00110-2

Portnyagin M, Hoernle K, Plechov P, Mironov N, Khubunaya S (2007) Constraints on mantle melting and composition and nature of slab components in volcanic arcs from volatiles (H2O, S, Cl, F) and trace elements in melt inclusions from the Kamchatka Arc. Earth Planet Sci Lett 255:53–69 Portnyagin M, Hoernle K, Plechov P, Mironov N, Khubunaya S (2007) Constraints on mantle melting and composition and nature of slab components in volcanic arcs from volatiles (H2O, S, Cl, F) and trace elements in melt inclusions from the Kamchatka Arc. Earth Planet Sci Lett 255:53–69

Ratajeski K, Sisson TW: Loss of iron to gold capsules in rock-melting experiments. Am Mineral 1999, 84: 1521–1527.

Roeder PL, Emslie RF: Olivine-liquid equilibrium. Contribut Mineral Petrol 1970, 19: 275–289. 10.1007/BF00371276

Rose-Koga EF, Shimizu N, Devidal J-L, Koga KT, Le Voyer M, Döbeli M: Investigation of F, S and Cl standards by ion probe and electron probe. Presented at the Eos Trans. AGU, Fall meeting supplement 2008.

Rose-Koga EF, Koga KT, Schiano P, Le Voyer M, Shimizu N, Whitehouse MJ, Clocchiatti R: Mantle source heterogeneity for South Tyrrhenian magmas revealed by Pb isotopes and halogen contents of olivine-hosted melt inclusions. Chem Geol 2012, 334: 266–279. 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2012.10.033

Rüpke LH, Morgan JP, Hort M, Connolly JA: Are the regional variations in Central American arc lavas due to differing basaltic versus peridotitic slab sources of fluids? Geology 2002,30(11):1035–1038. 10.1130/0091-7613(2002)030<1035:ATRVIC>2.0.CO;2

Saal AE, Hauri EH, Langmuir CH, Perfit MR: Vapour undersaturation in primitive mid-ocean-ridge basalt and the volatile content of Earth’s upper mantle. Nature 2002,419(6906):451–455. 10.1038/nature01073

Sadofsky SJ, Portnyagin M, Hoernle K, van den Bogaard P: Subduction cycling of volatiles and trace elements through the Central American volcanic arc: evidence from melt inclusions. Contribut Mineral Petrol 2008, 155: 433–456. 10.1007/s00410-007-0251-3

Sandland TO, Du LS, Stebbins JF, Webster JD (2004) Structure of Cl-containing silicate and aluminosilicate glasses: A 35Cl MAS-NMR study. Geochimica Cosmochimica Acta 68(24):5059–5069

Schaller T, Dingwell DB, Keppler H, Knöller W, Merwin L, Sebald A: Fluorine in silicate glasses: a multinuclear nuclear magnetic resonance study. Geochimica Cosmochimica Acta 1992,56(2):701–707. 10.1016/0016-7037(92)90091-V

Shaw HR (1963) Obsidian-H2O viscosities at 1000 and 2000 bars in the temperature range 700°C–900°C. J Geophys Res 68:6337–6343

Shaw HR: Viscosities of magmatic liquids: an empirical method of prediction. Am J Sci 1972, 272: 870–893. 10.2475/ajs.272.9.870

Shaw AM, Hauri EH, Behn MD, Hilton DR, Macpherson CG, Sinton JM: Long-term preservation of slab signatures in the mantle inferred from hydrogen isotopes. Nat Geosci 2012, 5: 224–228. 10.1038/ngeo1406

Shimizu K, Shimizu N, Komiya K, Suzuki K, Maruyama S, Tatsumi Y (2009) CO2-rich komatiitic melt inclusions in Cr-spinels within beach sand from Gorgona Island, Colombia. Earth Planet Sci Lett 299:33–43

Sisson TW, Grove TL (1993) Temperatures and H2O contents of low-MgO high-alumina basalts. Contribut Mineral Petrol 113(2):167–184

Sorbadere F, Schiano P, Metrich N, Garaebiti E: Insights into the origin of primitive silica-undersaturated arc magmas of Aoba volcano (Vanuatu arc). Contribut Mineral Petrol 2011, 162: 995–1009. 10.1007/s00410-011-0636-1

Stebbins JF, Du LS (2002) Chloride ion sites in silicate and aluminosilicate glasses: a preliminary study by 35Cl solid-state NMR. Am Mineral 87(2–3):359–363

Stolper EM, Newman S: The role of water in the petrogenesis of Mariana trough magmas. Earth Planet Sci Lett 1994, 121: 293–325. 10.1016/0012-821X(94)90074-4

Straub SM, Layne GD: The systematics of chlorine, fluorine, and water in Izu arc front volcanic rocks: Implications for volatile recycling in subduction zones. Geochimica Cosmochimica Acta 2003, 67: 4179–4203. 10.1016/S0016-7037(03)00307-7

Straub SM, Layne GD, Schmidt A, Langmuir CH (2004) Volcanic glasses at the Izu arc volcanic front: New perspectives on fluid and sediment melt recycling in subduction zones. Geochem Geophys Geosyst 5(1):ᅟ, doi: 10.1029/2002GC000408

Toplis MJ: The thermodynamics of iron and magnesium partitioning between olivine and liquid: criteria for assessing and predicting equilibrium in natural and experimental systems. Contribut Mineral Petrol 2005, 149: 22–39. 10.1007/s00410-004-0629-4

Vigouroux N, Wallace P, Kent AJR: Volatiles in High-K Magmas from the Western Trans-Mexican volcanic belt: evidence for fluid fluxing and extreme enrichment of the mantle wedge by subduction processes. J Petrol 2008, 49: 1589. 10.1093/petrology/egn039

Wallace PJ: Volatiles in subduction zone magmas: concentrations and fluxes based on melt inclusion and volcanic gas data. J Volc Geother Res 2005,140(1):217–240. 10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2004.07.023

Webster JD: The exsolution of magmatic hydrosaline chloride liquids. Chem Geol 2004,210(1):33–48. 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2004.06.003

Workman RK, Hart SR: Major and trace element composition of the depleted MORB mantle (DMM). Earth Planet Sci Lett 2005,231(1):53–72. 10.1016/j.epsl.2004.12.005

Wu J, Koga KT: Fluorine partitioning between hydrous minerals and aqueous fluid at 1 GPa and 770°C–947°C: A new constraint on slab flux. Geochimica Cosmochimica Acta 2013, 119: 77–92. 10.1016/j.gca.2013.05.025

Wysoczanski R, Wright I, Gamble JA, Hauri EH, Luhr J, Eggins SM, Handler M: Volatile contents of Kermadec Arc–Havre trough pillow glasses: fingerprinting slab-derived aqueous fluids in the mantle sources of arc and back-arc lavas. J Volc Geother Res 2006, 152: 51–73. 10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2005.04.021

Zeng Q, Stebbins JF (2000) Fluoride sites in aluminosilicate glasses: high-resolution 19 F NMR results. Am Mineral 85(5–6):863–867

Zimova M, Webb S (2006) The effect of chlorine on the viscosity of Na2O-Fe2O3-Al2O3-SiO2 melts. Am Mineral 91(2–3):344–352

Acknowledgements

This research was financed by the French Government Laboratory of Excellence initiative n°ANR-10-LABX-0006, the Région Auvergne and the European Regional Development Fund. This is Laboratory of Excellence ClerVolc contribution number 127. Critical reviews from AE Bjorn Mysen and three anonymous reviewers were greatly appreciated. CD thanks Robert Dennen for his help with English revisions.

This research article belongs to no. 4 section: Solid Earth Sciences.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

KTK conceived and designed the study. CD carried out the experimental study, obtained analytical data with NS, and wrote the manuscript. KTK, ML, and NS collaborated with the corresponding author in the construction of manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Dalou, C., Koga, K.T., Le Voyer, M. et al. Contrasting partition behavior of F and Cl during hydrous mantle melting: implications for Cl/F signature in arc magmas. Prog. in Earth and Planet. Sci. 1, 26 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40645-014-0026-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40645-014-0026-1