Abstract

Background

Foodborne diseases associated with the consumption of meat and its products are of public health significance worldwide. The study is, therefore, aimed to estimate the prevalence and the antimicrobial resistance profile of some bacterial pathogens isolated from meats and its products in Ethiopia.

Methods

Literature search was conducted from major electronic databases and indexing services including PubMed/MEDLINE, Google Scholar, Science Direct and WorldCat. Both published and unpublished studies addressing the prevalence and antimicrobial resistance profiles of some bacterial pathogens in meat and its products in Ethiopia were included for the study. Data were extracted with structured format prepared in Microsoft Excel and exported to STATA 15.0 software for the analyses. Pooled estimation of outcome measures was performed with DerSimonian-Laird random-effects model at 95% confidence level. Degree of heterogeneity of studies was presented with I2 statistics. Publication bias was conducted with comprehensive meta-analysis version 3.0 software and presented with funnel plots supplemented by Begg’s and Egger’s tests. The study protocol is registered on PROSPERO with reference number ID: CRD42018106361.

Results

A total of 27 original studies with 7828 meat samples were included for systematic review and meta-analysis. The pooled prevalence of Salmonella spp., E. coli O157:H7, Staphylococcus spp. and L. monocytogenes was 9, 5, 21 and 4%, respectively. Based on animal species, the prevalence of Salmonella in goat, mutton, beef, pork, chicken, and fish meat was 18, 6, 10, 11, 14 and 2%, respectively. The prevalence of E. coli O157:H7 in beef, mutton, goat and other animal meats was 6, 6, 3 and 21%, respectively. The prevalence of Staphylococcus spp. in beef and other animal meats was 21 and 22%, respectively. Based on the sample source, Salmonella prevalence in abattoir, butcher and market was 6, 36, and 11%, respectively. The E. coli O157:H7 prevalence in abattoir, butcher and market was 5, 6 and 8%, respectively. The bacterial isolates showed different antimicrobial resistance profiles against selected drugs. About 25% of the Salmonella spp. was resistant to ampicillin. Besides, 9% of Salmonella spp. and 2% of E. coli O157:H7 were found to be resistant to ceftriaxone. The pooled estimates showed that 10% of E. coli O157:H7 isolates were resistant to ciprofloxacin. Moreover, Salmonella spp. (6%), L. monocytogenes (5%) and E. coli O157:H7 (2%) were resistant to gentamicin.

Conclusion

This study revealed that pooled prevalence of bacterial pathogens is relatively high as compared to other countries and hence, there is a need to design intervention to ensure meat safety in the sector.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Meat is a nutrient-rich food which provides vital amount of proteins, vitamins and minerals with greater bioavailability than other food sources (McAfee et al., 2010). However, it has been recognized as the main vehicle for the transmission of foodborne pathogens to humans (EFSA, 2013). The water activity of fresh meat and its optimum pH play the major role for the growth of microorganisms. As a result, meat is considered as highly perishable foodstuff. Cross contamination of carcasses and meat products occur during subsequent handling, processing, preparation and distribution (Dave & Ghaly, 2011).

The safety of meat may be affected by many biological, chemical and physical hazards; although the biological hazards pose the highest foodborne risk for meat consumers (Norrung & Buncic, 2008). The pathogenic microorganisms possess greater socioeconomic impact due to their potential to contaminate meat and meat based products (Buzby et al., 2001). From the biological hazards, bacterial pathogens are the most serious concern regarding the issues of meat safety to consumers (Sofos, 2008).

Contamination of meat with foodborne pathogens is a major public health issue. Hence, the quantitative synthesis of studies is important to estimate the level of contamination of meat. In this meta-analysis, the population is defined as meat and meat-based products surveyed at abattoirs and retail establishments/markets in Ethiopia. The primary outcome of interest is the prevalence of pathogens, while the antibiotic resistance status of the pathogen is considered as a secondary outcome.

In Ethiopia, studies have been conducted on the prevalence of bacterial pathogens on meats in different parts of the meat chain and settings. These individual studies alone would not, however, show the nationwide burden of bacterial pathogens in meat unless evidence is generated from pooled estimation of the results of primary studies to provide a common national figure. Therefore, this systematic review and meta-analysis was aimed to estimate the overall prevalence of bacterial pathogens and their antimicrobial resistance profile in meat and meat products in Ethiopian abattoirs and retail establishments.

Methods

Study protocol

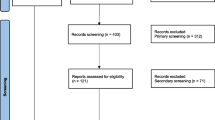

The identification of records, screening of titles and abstracts as well as evaluation of eligibility of full texts for final inclusion was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) flow diagram (Moher et al., 2009a). PRISMA checklist (Moher et al., 2009b) was also strictly followed while conducting this systematic review and meta-analysis. The study protocol is registered on PROSPERO with reference number ID: CRD42018106361 and Available from: http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.php?ID=CRD42018106361

Data sources and search strategies

The literature search was carried out through visiting electronic databases and indexing services. The PubMed/MEDLINE, Google Scholar, and WorldCat were used as main sources of data. Besides, other supplementary sources including Research Gate, Science Direct and University repositories were searched to retrieve relevant data. Excluding the non-explanatory terms, the search strategies included important key words and indexing terms: Meat (MeSH), “meat products”, meat*, bacteria (MeSH), bacterial* “antimicrobial resistance”, “antibacterial resistance”, “antimicrobial susceptibility”, and “Ethiopia”. The Boolean logical connectors (AND and OR), and truncation were applied for appropriate search and identification of records for the research question.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The papers with original article written in English language, possessed approved microbiological methods for pathogen detection and contain sufficient and extractable data were included in the meta-analysis. Having assessed all the information from the recovered publications, online records available from 2008 to June, 2018 were considered as appropriate for eligibility assessment. Furthermore, only studies focusing on meat and meat-based products were included. All review articles and original articles conducted outside Ethiopia, articles with irretrievable full texts (after requesting full texts from the corresponding authors via email and/or Research Gate) and records with unrelated outcomes of interest were excluded during screening and eligibility assessment.

Screening and eligibility of studies

Records identified from various electronic databases, indexing services and directories were exported to ENDNOTE reference software version 8.2 (Thomson Reuters, Stamford, CT, USA) with compatible formats. Duplicate records were identified, documented and removed with ENDNOTE. Some duplicates were addressed manually due to variation in reference styles across sources. Thereafter, two authors (AZ and MS) independently screened the title and abstracts with predefined inclusion criteria. Two authors (AZ and MS) also independently collected full-texts and evaluated the eligibility of them for final inclusion. In each case, the rest authors played a critical role in solving discrepancies arose between two authors to come up to consensus.

Data extraction

With the help of standardized data abstraction format prepared in Microsoft Excel, authors independently extracted important data related to study characteristics (study area, first author, year of publication, study design, slaughtered animals, sample source, sample type, sample size) and outcome of interests (number of positive samples (prevalence) per bacterium and number of resistant isolates (if any) per bacterium in each positive sample).

Quality assessment of studies

The quality of studies was evaluated according to Newcastle-Ottawa scale adapted for cross-sectional studies (Newcastle- Ottawa, 2016) and graded out of 10 points (stars). For ease of assessment, the tool included important indicators categorized into three major sections: (1) the first section assesses the methodological quality of each study and weighs a maximum of five stars (2) the second section considers comparability of the study and takes 2 stars (3) the remaining section assess outcomes with related statistical analysis. This critical appraisal was conducted to assess the internal (systematic error) and external validity of studies and reduce the risk of biases. The mean score of two authors were taken for final decision and studies with score greater than or equal to five were included.

Outcome measurements

The primary outcome measure is the prevalence of clinically relevant bacterial isolates in meat and meat products sampled in abattoir and retail establishments in Ethiopia. The pooled prevalence was calculated per bacterium. The calculation was conducted for both gram positive and gram negative bacterial isolates including Staphylococcus spp., L. monocytogenes, E. coli O157:H7, and Salmonella spp. The secondary outcome measure is the antimicrobial resistance status of the above-mentioned bacteria against selected antimicrobials from different categories (ceftriaxone, gentamicin, ciprofloxacin and ampicillin). Subgroup analyses were also conducted based on the spatial source of meat and slaughtered animal type.

Data processing and analysis

The relevant data were extracted from selected studies using format prepared in Microsoft Excel and exported to STATA 15.0 software for analyses of pooled estimate of outcome measures and subgroup analyses. Subgroup analysis for the primary outcome (prevalence of selected pathogens) was done by sample source (abattoirs, butcher and market), and slaughtered animal types. Considering variation in true effect sizes across population, Der-Simonian-Laird’s random effects model was applied for the analysis at 95% confidence level.

The significance of heterogeneity of the studies was assessed using I2 statistics (based on Cochran's Q test, I2 returns the percent variation across studies. The formula is: I2 = 100% * (Q – df)/Q, Where: Q = Cochran’s Q and df = degrees of freedom. Comprehensive Meta-analysis version-3 software (Biostat, Englewood, New Jersey, USA) was used for publication bias assessment. The presence of publication bias was evaluated by using the Begg’s and Egger’s tests and presented with funnel plots of standard error of Logit event rate (proportion) (Begg & Mazumdar, 1994; Egger et al., 1997). A statistical test with a p-value less than 0.05 (one tailed) was considered significant.

Results

Search results

A total of 189 potentially relevant studies were identified from several sources including PubMed/MEDLINE, Google Scholar and WorldCat. From these, 18 duplicated articles were removed with the help of ENDNOTE and manual tracing. The remaining 171 records were screened using their titles and abstracts and 113 of them were excluded. Full texts of 58 records were then evaluated for eligibility. From these, 31 articles were excluded due to the outcome of interest was found missing, insufficient and/or ambiguous. Finally, a total of 27 articles fulfilled the eligibility criteria and quality assessment and thus included for systematic review and meta-analysis (Fig. 1).

Study characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of 27 eligible studies with 7828 samples which were considered for determining the prevalence of bacterial pathogens and their antimicrobial resistance status. The studies were published in the year between 2008 and 2018. All the selected studies were cross-sectional study design in nature. The majority of meat samples were investigated from beef only (Abdissa et al., 2017; Alemu & Zewde, 2012; Atnafie et al., 2017; Bedasa et al., 2018; Beyi et al., 2017; Dagnachew, 2017; Garedew et al., 2015a; Garedew et al., 2015b; Gebretsadik et al., 2011; Abunna et al., 2016; Kore et al., 2017; Mengistu et al., 2017; Muluneh & Kibret, 2015; Wabeto et al., 2017; Adugna et al., 2018). The rest animal species were goat (Dulo, 2014; Dulo et al., 2015; Ferede, 2014), sheep (Mulu & Pal, 2016), and others (Ejo et al., 2016; Kebede et al., 2014; Senait & Moorty, 2016; Azage & Kibret, 2017). Samples of meat from two or more animals were also taken in four studies (Bekele et al., 2014; Hiko et al., 2008; Kebede et al., 2016; Zewdu & Cornelius, 2009). The foodborne pathogens such as Staphylococcus spp. and L. monocytogenes were the outcomes/pathogens with the fewest observations retrieved: Staphylococcus spp. (with only four published studies) and L. monocytogenes (with only three published studies) as their presence in meats have not been widely surveyed. The average quality score of included studies ranges from 6.5 to 9 as per the Newcastle-Ottawa scale adapted for cross sectional studies (Table 1).

The antimicrobial resistance profile of common bacterial isolates against four major antimicrobial agents (ampicillin, gentamicin, ciprofloxacin and ceftriaxone) is summarized in Table 2. Out of 722 positive samples, 475 of them were tested for susceptibility. Regardless of the nature of bacterial pathogens, 73, 25, 17 and 15 bacteria were found resistant to ampicillin, ceftriaxone, gentamicin and ciprofloxacin, respectively.

Study outcomes

Primary outcomes: Prevalence of bacterial isolates

The study showed that different bacterial pathogens have been detected in meat and meat products in Ethiopia at different level of occurrence (Table 1). The forest plot indicated that the pooled prevalence of Salmonella in meat and meat products was found to be 9% (95% CI: 6.0, 12.0) (Fig. 2).

The highest prevalence was observed in goat meat 18% (95% CI: 13.0, 22.0) followed by chicken meat, 14% (95% CI: 10.0, 19.0), whereas the least prevalence was observed in fish meat 2% (95% CI: 0.00, 5.00) (Table 3). The prevalence of Salmonella in butcher, market and abattoirs was 36% (95% CI: 26.0, 44.0), 11% (95% CI: 6.0, 16.0) and 6% (95% CI: 3.0, 9.0), respectively (Table 4).

The pooled estimate of E. coli O157:H7 was found to be 5% (95% CI: 4.0, 7.0) (Fig. 3) and subgroup analysis indicated that the highest prevalence was recorded in beef and sheep meat with value of 6% in each (Table 3). The prevalence of E. coli O157:H7 in meats collected from market, abattoir and butcher was 8% (95% CI: 4.0, 12.0), 5% (95% CI: 3.0, 7.0) and 6% (95% CI: 2.0, 9.0), respectively (Table 4).

The pooled estimate of Staphylococcus spp. isolated from meat samples was 21% (95% CI: 12, 30) (Fig. 4). Comparable pooled estimates were observed across spatial sources of meat (21%, 20% and 22% from abattoir, butcher and market, respectively) (Table 4). The overall prevalence of L. monocytogenes in meat samples was 4% (95% CI: 2.0, 6.0) (Fig. 5). Beef and sheep meat were the only sources of this bacterium with 4.1% prevalence in each (Table 3). The highest prevalence (6%; 95% CI: 3.0, 7.0) of L. monocytogenes was reported from meat samples collected from butcher (Table 4).

Secondary outcomes: Antimicrobial resistance profiles of bacterial isolates

The bacterial isolates showed different antimicrobial resistance profile against selected agents. About 25% (95% CI: 10.0, 40.0) of the Salmonella spp. were found resistant to ampicillin. Besides, 9% (95% CI: 2.0, 15.0) of Salmonella spp. and 2% (95% CI: 0.0, 5.0) of E. coli O157:H7 isolates were found to be resistant to ceftriaxone. The pooled estimate indicated that 10% of E. coli O157:H7 isolates were resistant to ciprofloxacin. Salmonella spp. (6%), L. monocytogenes (5%) and E. coli O157:H7 (2%) were resistant to gentamicin (Table 5).

Publication bias

Funnel plots of standard error with Logit event rate (prevalence of bacterial isolates) supplemented by statistical tests confirmed that there is some evidence of publication bias on studies reporting the prevalence of bacterial isolates from meat and meat products in Ethiopia (Begg’s test, p = 0.003; Egger’s test, p = 0.000) (Fig. 6).

Discussion

Out of 27 original studies with 7828 meat samples included in this study, the pooled prevalence of Salmonella in meat and meat products was 9%. This result is in concordance with the meta-analysis conducted in Portugal where the prevalence of Salmonella spp. in meats was 6% (95% CI: 4, 9%) (Xavier et al., 2014). The finding is much higher than the report made by United States Department of Agriculture, Food Safety and Inspection Service (USDA-FSIS: United States Department of Agriculture, Food Safety and Inspection Service, 2014) which showed that the Salmonella prevalence in ground beef was 1.9% in United States. This difference might be due to the fact that the presence of poor food handling practice, lack of slaughtering facility and poor animal health management at primary production and substandard transport of animal meat contributing to high prevalence bacterial pathogen in Ethiopia. Furthermore, reduced prevalence of Salmonella spp. might be attributed to effective management strategies of pathogens at different stages of production in developed countries.

In a meta-analysis conducted in Portugal, the prevalence of Salmonella in raw and minced beef were 1.9% (95% CI: 0.5, 7.2%) and 1.5% (95% CI: 0.3, 7.8%), respectively (Xavier et al., 2014). Compared to studies conducted in developed countries, the subgroup analysis indicated that the pooled estimate of Salmonella in beef meat is much higher in Ethiopia, 10.0% (95% CI: 6.0, 12.0). The highest Salmonella prevalence was observed in goat meat 18% (95% CI: 13.0, 22.0). The prevalence of Salmonella on chicken meat (14%) is also higher than the European surveys which indicated that the overall pooled estimate of Salmonella spp. in poultry meat was 7.10% (95% CI: 4.60, 10.8%) (Gonçalves-Tenório et al., 2018). Generally, this finding supports the conclusion made by Islam et al. (Islam et al., 2014) who identified slaughtered animal species as one of the sources of variation when estimating the prevalence of bacterial pathogens.

The least prevalence of Salmonella was observed in fish meat, 2.0% (95% CI: 0.0, 5.0). In line with this result, in United States, the prevalence of Salmonella in domestic fish and its products as well as imported fish and its products was 1.3% and 7.2%, respectively (Olgunoğlu, 2012). Animal waste can be introduced directly through bird droppings in ponds or indirectly through runoff. Fish and fish products may carry Salmonella spp., particularly if they are caught in areas contaminated with fecal pollution. Moreover, unsafe handling and packaging may contribute to its contamination.

Our study indicated that the pooled prevalence of E. coli O157:H7 isolated from meat and meat products was 5% which is much higher than a study conducted by Hill et al. (Hill et al., 2011) who reported that E. coli O157:H7 was detected on 0.25% of ground beef and 0.82% of trimmed beef meats in USA. Similarly, very low (1.7%) E. coli O157:H7 prevalence was detected on manufactured beef collected at the processing facility in Australia (Kiermeier et al., 2011).

The highest prevalence was recorded in beef and sheep meats with estimates of 6% in each, whereas the lowest prevalence (3%) was recorded in goat meat. Similarly, Jacob et al. (Jacob et al., 2013) reported that the prevalence of E. coli O157:H7 on goat carcasses was 2.7% (95% CI: 0.8, 4.5%) in United States. In this regard, ruminants, particularly cattle, are considered as the primary reservoirs for E. coli O157:H7, where the organism typically colonizes the lower gastrointestinal tract (Low et al., 2005). In Ethiopia beef is most commonly consumed foods, however, the risk of acquiring E. coli O157:H7 from beef meat appears higher than the risk from meats of other animal species. Many outbreaks of E. coli O157:H7 are usually associated with foods from cattle or their fecal contamination (CDC, 1991).

The pooled estimate of Staphylococcus spp. was found to be 21% in meat and meat products which is in trajectory with the prevalence of S. aureus in Portuguese meat product samples, 22.6% (95% CI: 15.4, 31.8%) (Xavier et al., 2014). The high occurrence of Staphylococcus spp. in meat and meat products is an indicator of hygiene deficiency during processing of meat (Rajkovic, 2012).

In this study, the overall prevalence of L. monocytogenes isolated from beef and mutton meat was 4%. Comparable estimate was reported in Ireland where the prevalence of L. monocytogenes in meat products was 4.2% (Leong et al., 2014). However, much higher prevalence of L. monocytogenes (18.7%) was reported in raw meat and raw meat products in Estonia (Kramarenko et al., 2013). The live animals may contribute little to the total contamination of the abattoir. Nevertheless, the L. monocytogenes may be introduced from potential environment and dirty transport crates into the meat production chain at different level. The contamination of carcass by L. monocytogenes is likely to occur due to poor handling by retailers and abattoir workers.

Most of bacterial pathogens were more prevalent in meats samples collected from retails as compared to meat samples collected from abattoirs. Correspondingly, the bacterial pathogen prevalence was globally lower in carcasses at the slaughter house level and higher in meat cuts and minced beef at retail (ECDC, 2013; Stevens et al., 2006). The temperature fluctuation during distribution, meat contamination by handlers, lack of hygiene and unsafe loading and unloading practices might have contributed for slight increment of meat contamination in retail outlets (Rajkovic, 2012). The high cost of cold storage equipment can also be key factors impeding the transportation of meat under refrigeration conditions in developing countries. Likewise, Gill et al. (Gill & McGinnis, 2000) reported that raw beef sold at retail outlets is subjected to a long chain of slaughtering and transportation where each step poses a potential risk of microbial contamination. Whereas, in abattoirs, a variety of decontamination measures might be employed during carcass processing in order to reduce the microbial load and contamination of carcass with pathogens.

Meta-analysis was conducted for antimicrobial susceptibility profile of bacterial isolates from subset of studies to which the secondary outcome measures were considered. The antimicrobial resistance profile of bacterial isolates from meat and meat products was found less than 10% in majority of estimates. However, slightly higher resistance profile (25% of Salmonella isolates) was recorded against ampicillin. To this end, higher prevalence (38%) of antimicrobial resistance Salmonella isolates against ampicillin was reported from chicken meat and their processing environment in Brazil (Medeiros et al., 2011). In the present study, 10% of E. coli O157:H7 isolates were resistant against ciprofloxacin. Despite a temporal variation, a study conducted in China in 2010 noted 4.1% antimicrobial resistance E. coli isolates against ciprofloxacin (Jiang et al., 2012). Antimicrobial resistance profile of meat borne pathogens might vary spatially and temporally due to sample type, environmental contamination and exposure, farm management system and antimicrobial use.

Implication and limitation of the study

According to the evidence generated from the meta-analysis, the contamination of meat and meat products requires stringent management on the area of food safety in meat sector in Ethiopia. The national food, medicine and health care administration and control authority and policy makers could make use of the estimates as inputs to enforce food safety measures. In this study, sufficient data was not found to assess the seasonal effect on the prevalence of bacterial pathogens in meat. Likewise, the risk factors of meat and meat products contamination along the production chain were not addressed. In most of the studies, there was lack of enumeration or bacterial load determination which indicates the actual safety status of food/ meat. Besides, very few reports were available for some pathogens from meat and meat products.

Most of the retrieved studies were carried out in slaughterhouses and markets in urban area of the country where most abattoirs are located therefore, the pooled prevalence estimates of contaminated meat items should not be generalized for rural and smaller settings of the country. All these limitations are clear gaps for further research in the area of meat safety in Ethiopia.

Conclusion

Relatively high prevalence of bacterial pathogens observed in meat and its products in Ethiopia, as highlighted in this review, may possibly be considered as potential sources of human foodborne illnesses. The results justify the need for strict measures to reduce contamination of carcasses in meat throughout the entire supply chain. The antibiotic resistance profiles of bacterial isolates in meat and its product was found lower. Relatively, Salmonella spp. showed high resistance against ampicillin.

Abbreviations

- CS:

-

Cross sectional

- MeSH:

-

Medical Subject Headings

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

References

Abdissa R, Haile W, Fite AT, Beyi AF, Agga GE, Edao BM, Tadesse F, Korsa MG, Beyene T, Beyene TJ, et al. Prevalence of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in beef cattle at slaughter and beef carcasses at retail shops in Ethiopia. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17(1):277.

Abunna F, Abriham T, Gizaw F, Beyene T, Feyisa A, Ayana D, Mamo B, Duguma R. Staphylococcus: isolation, identification and antimicrobial resistance in dairy cattle farms, municipal abattoir and personnel in and around Asella, Ethiopia. J Vet Sci Technol. 2016;7:383.

Adugna F, Pal M, Girmay G. Prevalence and Antibiogram assessment of Staphylococcus aureus in beef at municipal abattoir and butcher shops in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:5017685.

Alemu S, Zewde BM. Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance profiles of salmonella enterica serovars isolated from slaughtered cattle in Bahir Dar, Ethiopia. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2012;44(3):595–600.

Atnafie B, Paulos D, Abera M, Tefera G, Hailu D, Kasaye S. Occurrence of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in cattle feces and contamination of carcass and various contact surfaces in abattoir and butcher shops of Hawassa, Ethiopia. BMC Microbiol. 2017;17(1):24.

Azage M, Kibret M. The bacteriological quality, safety, and Antibiogram of salmonella isolates from fresh meat in retail shops of Bahir Dar City, Ethiopia. Int J Food Sci. 2017;2017:4317202.

Bedasa S, Shiferaw D, Abraha A, Moges T. Occurrence and antimicrobial susceptibility profile of Escherichia coli O157:H7 from food of animal origin in Bishoftu town, Central Ethiopia. International Journal of Food Contamination. 2018;5(1):2.

Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50(4):1088–101.

Bekele T, Zewde G, Tefera G, Feleke A, Zerom K. Escherichia coli O157: H7 in raw meat in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: prevalence at an abattoir and retailers and antimicrobial susceptibility. International Journal of Food Contamination. 2014;1(1):4.

Beyi AF, Fite AT, Tora E, Tafese A, Genu T, Kaba T, Beyene TJ, Beyene T, Korsa MG, Tadesse F, et al. Prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility of Escherichia coli O157 in beef at butcher shops and restaurants in Central Ethiopia. BMC Microbiol. 2017;17(1):49.

Buzby J, Frenzen P, Rasco B. Product liability and foodborne illness. Washington, DC: Food and Rural Economics Division. Economic Research Service, US Department of Agriculture; 2001.

CDC. Foodborne outbreak of gastroenteritis caused by Escherichia coli O157: H7--North Dakota, 1990. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1991;40(16):265.

Dagnachew D. Distribution and antimicrobial resistance of salmonella serotypes in minced beef, calves and humans in Bishoftu and Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Journal of Parasitology and Vector Biology. 2017;9(5):64–72.

Dave D, Ghaly AE. Meat spoilage mechanisms and preservation techniques: a critical review. Am J Agric Biol Sci. 2011;6(4):486–510.

Dulo F. Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance profile of Escherichia coli O157: H7 in goat slaughtered in Dire Dawa municipal abattoir as well as food safety knowledge, attitude and hygiene practice assessment among slaughter staff, Ethiopia. Addis Ababa: Addis Ababa University; 2014.

Dulo F, Feleke A, Szonyi B, Fries R, Baumann MP, Grace D. Isolation of multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli O157 from goats in the Somali region of Ethiopia: a cross-sectional, Abattoir-Based Study. PloS one. 2015;10(11):e0142905.

ECDC E. The European Union summary report on trends and sources of zoonoses, zoonotic agents and foodborne outbreaks in 2011. EFSA J. 2013;11(4):3129.

EFSA: The European Union summary report on trends and sources of zoonoses, zoonotic agents and food-borne outbreaks. Parma, EFSA 2013, 11(4):3129.

Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 1997;315(7109):629–34.

Ejo M, Garedew L, Alebachew Z, Worku W. Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance of salmonella isolated from animal-origin food items in Gondar, Ethiopia. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:4290506.

Ferede B. Isolation, identification, antimicrobial susceptibility test and public awareness of salmonella on raw goat meat at Dire Dawa municipal abattoir, eastern Ethiopia. Addis Ababa: Addis Ababa University; 2014.

Garedew L, Hagos Z, Addis Z, Tesfaye R, Zegeye B. Prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of salmonella isolates in association with hygienic status from butcher shops in Gondar town, Ethiopia. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2015a;4:21.

Garedew L, Taddese A, Biru T, Nigatu S, Kebede E, Ejo M, Fikru A, Birhanu T. Prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility profile of listeria species from ready-to-eat foods of animal origin in Gondar town, Ethiopia. BMC Microbiol. 2015b;15:100.

Gebretsadik S, Kassa T, Alemayehu H, Huruy K, Kebede N. Isolation and characterization of listeria monocytogenes and other listeria species in foods of animal origin in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. J. Infect. Public Health. 2011;4(1):22–9.

Gill C, McGinnis J. Contamination of beef trimmings with Escherichia coli during a carcass breaking process. Food Res Int. 2000;33(2):125–30.

Gonçalves-Tenório A, Silva BN, Rodrigues V, Cadavez V, Gonzales-Barron U. Prevalence of pathogens in poultry meat: a meta-analysis of European published surveys. Foods. 2018;7(5):69.

Hiko A, Asrat D, Zewde G. Occurrence of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in retail raw meat products in Ethiopia. Journal of infection in developing countries. 2008;2(5):389–93.

Hill WE, Suhalim R, Richter HC, Smith CR, Buschow AW, Samadpour M. Polymerase chain reaction screening for salmonella and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli on beef products in processing establishments. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2011;8(9):1045–53.

Islam MZ, Musekiwa A, Islam K, Ahmed S, Chowdhury S, Ahad A, Biswas PK. Regional variation in the prevalence of E. coli O157 in cattle: A meta-analysis and meta-regression. PloS one. 2014;9(4):e93299.

Jacob ME, Foster DM, Rogers AT, Balcomb CC, Shi X, Nagaraja TG. Evidence of non-O157 Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli in the feces of meat goats at a U.S. slaughter plant. J Food Prot. 2013;76(9):1626–9.

Jiang H-X, Tang D, Liu Y-H, Zhang X-H, Zeng Z-L, Xu L, Hawkey PM. Prevalence and characteristics of β-lactamase and plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance genes in Escherichia coli isolated from farmed fish in China. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67(10):2350–3.

Kebede A, Kemal J, Alemayehu H, Habte Mariam S. Isolation, identification, and antibiotic susceptibility testing of salmonella from slaughtered bovines and ovines in Addis Ababa abattoir Enterprise, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Int J Bacteriol. 2016;2016:3714785.

Kebede T, Afera B, Taddele H, Bsrat A. Assessment of bacteriological quality of sold meat in the butcher shops of Adigrat, Tigray, Ethiopia; 2014.

Kiermeier A, Mellor G, Barlow R, Jenson I. Assumptions of acceptance sampling and the implications for lot contamination: Escherichia coli O157 in lots of Australian manufacturing beef. J Food Prot. 2011;74(4):539–44.

Kore K, Asrade B, Demissie K, Aragaw K. Characterization of salmonella isolated from apparently healthy slaughtered cattle and retail beef in Hawassa, southern Ethiopia. Prev Vet Med. 2017;147:11–6.

Kramarenko T, Roasto M, Meremäe K, Kuningas M, Põltsama P, Elias T. Listeria monocytogenes prevalence and serotype diversity in various foods. Food Control. 2013;30(1):24–9.

Leong D, Alvarez-Ordóñez A, Jordan K. Monitoring occurrence and persistence of listeria monocytogenes in foods and food processing environments in the Republic of Ireland. Front Microbiol. 2014;5:436.

Low JC, McKendrick IJ, McKechnie C, Fenlon D, Naylor SW, Currie C, Smith DG, Allison L, Gally DL. Rectal carriage of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157 in slaughtered cattle. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71(1):93–7.

McAfee AJ, McSorley EM, Cuskelly GJ, Moss BW, Wallace JM, Bonham MP, Fearon AM. Red meat consumption: an overview of the risks and benefits. Meat Sci. 2010;84(1):1–13.

Medeiros MA, Oliveira DC, Rodrigues Ddos P, Freitas DR. Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance of salmonella in chicken carcasses at retail in 15 Brazilian cities. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2011;30:555–60.

Mengistu S, Abayneh E, Shiferaw D. E. coli O157: H7 and Salmonella Species: Public Health Importance and Microbial Safety in Beef at Selected Slaughter Houses and Retail Shops in Eastern Ethiopia. J Vet Sci Technol. 2017;8(468):2.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman D: Prisma 2009 checklist. available at: www prisma-statement org (Accessed 28 Apr 2018) 2009b.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009a;6(7):e1000097.

Mulu S, Pal M. Studies on the Prevalence, Risk Factors, Public Health Implications and Antibiogram of Listeria monocytogenes in Sheep Meat Collected from Municipal Abattoir and Butcher Shops in Addis Ababa. Journal of Foodborne and Zoonotic Diseases. 2016;4(1):01–14.

Muluneh G, Kibret M. Salmonella spp. and risk factors for the contamination of slaughtered cattle carcass from a slaughterhouse of Bahir Dar town, Ethiopia. Asian Pac J Trop Dis. 2015;5(2):130–5.

Newcastle- Ottawa: Scale customized for cross-sectional studies. 2016. Available from https://static-content.springer.com/esm/art%3A10.1186%2F1471-2458-13-154/MediaObjects/12889_2012_5111_MOESM3_ESM.doc.

Norrung B, Buncic S. Microbial safety of meat in the European Union. Meat Sci. 2008;78(1–2):14–24.

Olgunoğlu İA. Salmonella in fish and fishery products. In: Salmonella-A Dangerous Foodborne Pathogen. edn.: InTech; 2012.

Rajkovic A. Incidence, growth and enterotoxin production of Staphylococcus aureus in insufficiently dried traditional beef ham “govedja pršuta” under different storage conditions. Food Control. 2012;27(2):369–73.

Senait G, Moorty PA. Isolation and identification of staphylococcus species from ready-to-eat meat products in and around Debre-Zeit, Ethiopia. Int J Res Agri Forest. 2016;3(4):6-16.

Sofos JN. Challenges to meat safety in the 21st century. Meat Sci. 2008;78(1–2):3–13.

Stevens A, Kaboré Y, Perrier-Gros-Claude J-D, Millemann Y, Brisabois A, Catteau M, Cavin J-F, Dufour B. Prevalence and antibiotic-resistance of salmonella isolated from beef sampled from the slaughterhouse and from retailers in Dakar (Senegal). Int J Food Microbiol. 2006;110(2):178–86.

USDA-FSIS: United States Department of Agriculture, Food Safety and Inspection Service. Progress Report on Salmonella and Campylobacter Testing of Raw Meat and Poultry Products, CY 1998–2013. Available at https://www.fsis.usda.gov/.../Progress-Report-Salmonella-Campylobacter-CY2013. Accessed in Aug 2018. 2014b.

Wabeto W, Abraham Y, Anjulo AA. Detection and identification of antimicrobial-resistant Salmonella in raw beef at Wolaita Sodo municipal abattoir, Southern Ethiopia. J Health Popul Nutr. 2017;36(1):52.

Xavier C, Gonzales-Barron U, Paula V, Estevinho L, Cadavez V. Meta-analysis of the incidence of foodborne pathogens in Portuguese meats and their products. Food Res Int. 2014;55:311–23.

Zewdu E, Cornelius P. Antimicrobial resistance pattern of salmonella serotypes isolated from food items and personnel in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2009;41(2):241–9.

Acknowledgments

Authors thank Haramaya and Hawassa University staffs for their kindly support for realization of this Meta-analysis.

Funding

The authors acknowledge that this study was supported and made possible by funds from Feed the Future/USAID/LSIL project on food safety held in collaboration with Kansas State University and Hawassa University.

Availability of data and materials

All data used for the study are contained within the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AZ and MS performed the bibliographic searches, extracted, organized and analyzed the data; KA, JV, AK and YT, supervised the work, performed writing, and editing. AZ and MS also drafted the manuscript and prepared the final version for publication. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Zelalem, A., Sisay, M., Vipham, J. et al. The prevalence and antimicrobial resistance profiles of bacterial isolates from meat and meat products in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. FoodContamination 6, 1 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40550-019-0071-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40550-019-0071-z