Abstract

With improved survivorship in medulloblastoma, there has been an increasing incidence of late complications. To date, no studies have specifically addressed the risk of radiation-associated diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG) in medulloblastoma survivors. Query of the International DIPG Registry identified six cases of DIPG with a history of medulloblastoma treated with radiotherapy. All patients underwent central radiologic review that confirmed a diagnosis of DIPG. Six additional cases were identified in reports from recent cooperative group medulloblastoma trials (total n = 12; ages 7 to 21 years). From these cases, molecular subgrouping of primary medulloblastomas with available tissue (n = 5) revealed only non-WNT, non-SHH subgroups (group 3 or 4). The estimated cumulative incidence of DIPG after post-treatment medulloblastoma ranged from 0.3–3.9%. Posterior fossa radiation exposure (including brainstem) was greater than 53.0 Gy in all cases with available details. Tumor/germline exome sequencing of three radiation-associated DIPGs revealed an H3 wild-type status and mutational signature distinct from primary DIPG with evidence of radiation-induced DNA damage. Mutations identified in the radiation-associated DIPGs had significant molecular overlap with recurrent drivers of adult glioblastoma (e.g. NRAS, EGFR, and PTEN), as opposed to epigenetic dysregulation in H3-driven primary DIPGs. Patients with radiation-associated DIPG had a significantly worse median overall survival (median 8 months; range 4–17 months) compared to patients with primary DIPG. Here, it is demonstrated that DIPG occurs as a not infrequent complication of radiation therapy in survivors of pediatric medulloblastoma and that radiation-associated DIPGs may present as a poorly-prognostic distinct molecular subgroup of H3 wild-type DIPG. Given the abysmal survival of these cases, these findings provide a compelling argument for efforts to reduce exposure of the brainstem in the treatment of medulloblastoma. Additionally, patients with radiation-associated DIPG may benefit from future therapies targeted to the molecular features of adult glioblastoma rather than primary DIPG.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Medulloblastoma is the most common malignant pediatric brain tumor, and standard treatment includes surgical resection followed by adjuvant external beam radiation therapy (EBRT) and systemic chemotherapy [14]. As the prognosis of medulloblastoma has improved, late complications such as secondary malignant neoplasms (SMNs) have increased in frequency [15, 39]. While 10-year survival rates of medulloblastoma are now near 80%, the 20-year cumulative incidence of SMNs is reported to be as high as 20%, comprising 11.8% of late mortality [15, 29, 31, 39].

The elevated risk of SMNs in medulloblastoma survivors may be due to high doses of EBRT. The risks of glioma, the most common SMN reported after primary medulloblastoma, increase linearly with radiation dose [9, 19, 31, 42]. Radiation dosing for medulloblastoma varies based on clinical and molecular risk stratification, and standard treatment involves craniospinal irradiation (CSI) with a posterior fossa boost. No previous studies have assessed the risk of the development of radiation-associated DIPG in medulloblastoma survivors, which could impact the future dose and modality of radiation therapy in future clinical trials.

Diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG) is a rare infiltrative brainstem tumor, and patients rarely survive longer than 2 years after diagnosis. DIPG is diagnosed primarily by radiographic features showing an intrinsic lesion that encompasses at least 50% of the pons. When available, histology frequently shows features consistent with an infiltrating high-grade glioma (HGG). Approximately 80% of these tumors harbor a point mutation in the histone H3 (H3.3 and H3.1), which now defines the new histomolecular entity Diffuse Midline Glioma, H3K27M-mutant, and is associated with epigenetic dysregulation of neuro-developmental pathways and a worse prognosis than H3 wild-type DIPG [8]. Recent studies suggest that H3 mutants are distinct biological entities, and that H3.3 mutants alone may display a worse prognosis relative to H3 wild-type [10, 20].

There is a paucity of data specifically addressing the risk and molecular characteristics of radiation-associated DIPG among medulloblastoma survivors. A recent report performed genomic analysis of recurrent tumors of seventeen pediatric medulloblastoma patients [33]. The report revealed some of the tumors as secondary glioblastomas with known driver mutations and identified PDGFRA as a potential molecular target for therapy. Although this work addressed radiation-associated cancers following treatment for pediatric medulloblastoma, there were no pontine tumors and there remains no published incidence data for radiation-associated DIPG. Here, this report describes a poorly-prognostic molecular subgroup of H3 wild-type DIPG that occurs as a not infrequent complication of radiation therapy in survivors of pediatric medulloblastoma.

Materials and methods

Case acquisition

The International DIPG Registry (IDIPGR) was queried for cases of DIPG diagnosed after radiation treatment for primary medulloblastoma. Details of the registry’s structure and recruitment are described elsewhere [12]. Diagnosis of DIPG was confirmed by central radiology review by two primary neuroradiologists (BJ, JL). A Medline/PubMed and Google Scholar search was performed to identify any additional published cases. Various combinations of keywords were used including: medulloblastoma, diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma, brainstem glioma, pontine glioma, secondary malignant neoplasm. Articles dated from 1999 to 2017 were obtained and demographic, treatment, and survival data extracted as available. All patients diagnosed with primary medulloblastoma from age 0–21 years who were subsequently diagnosed with brainstem glioma were included. While it was not possible to review imaging for all cases obtained from primary literature, care was taken to exclude patients with focal (non-diffuse) brainstem tumors.

Methylation analyses of primary medulloblastoma

The medulloblastoma methylation-derived subgrouping was performed using the Infinium Assay with the Illumina MethylationEPIC BeadChip platform. DNA was extracted and isolated according to standard protocols, and bisulfite conversion was performed using the Zymo EZ DNA methylation kit. A support vector machine was trained on a cohort of medulloblastoma samples to develop a methylation-derived sub-classification prediction algorithm. The MethylationEPIC BeadChip 46 CpG dinucleotide signature algorithm and R statistical program (version 3.0.0) were used to classify the medulloblastoma tumor into one of four subgroups: Sonic hedgehog pathway activated (SHH), Wnt-pathway activated (WNT), Group 3, or Group 4. Quality control parameters were assessed using Illumina Genome Studio V2011.1 (Methylation Module, version 1.9.1000).

Karyotyping and immunohistochemistry of DIPG

Fresh tumor was disaggregated mechanically and enzymatically using collagenase V (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). The suspension cultures were incubated overnight or 24 h before harvest, and in-situ cultures were harvested after 3–12 days in culture. Karyotype was interpreted according to the International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature (ISCN 2013). Immunohistochemical studies were performed as previously published using the Discovery XT processor (Ventana Medical Systems) [40, 41]. In brief, immunostaining was performed using the rabbit polyclonal anti-H3K27me3 (07–449, Millipore, Billercia, MA; 1 μg/mL) or rabbit polyclonal anti-H3.3 K27 M (ABE419, Millipore, Billercia, MA; 0.5 μg/mL) antibodies. Streptavidin- HRP and DAB detection kit (Ventana Medical Systems) were used according to the manufacturer instructions.

Exome and transcriptome profiling of DIPG

For cases 1 and 3, frozen DIPG tumor and normal brain tissue from autopsy were submitted for whole exome (paired tumor and germline DNA) and transcriptome (tumor RNA) sequencing. Clinically-integrated sequencing was performed according to previously published methodology [26]. Nucleic acid preparation, high-throughput sequencing, and computational analysis were performed by the Michigan Center for Translational Pathology sequencing laboratory using standard protocols in adherence to the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments.

For case 6, only frozen DIPG tissue (no germline DNA sample) was submitted for whole exome sequencing (WES). This sample was processed through the GATK 3.6 variant analysis pipeline as a germline sample. After variants were called, variant annotation using SnpEff was completed to assign mutation information. This annotated VCF file was filtered using bcftools on a known set of specific genes/histones of interest to examine the mutational landscape. These gene specific variants then were examined further based on mutation effect (high, moderate) as to elucidate the presence of any non-synonymous variants, processed to remove common variants with ≥5% allele frequencies in 1000 Genomes Project (2015) [18], NHLBI Exome Sequencing Project 6500 (ESP6500) [16], Exome Aggregation Consortium dataset (http://exac.broadinstitute.org), and Genome Aggregation Database (http://gnomad.broadinstitute.org), and removed of non-recurrent somatic variants using annotations in the COSMIC v70 database (http://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cosmic).

Mutational signature

The somatic mutations in each of the DIPG samples from cases 1 and 3 processed through MiOncoseq sequencing platform [26] were categorized into one of the 96 possible categories: 6 classes of base substitution (C > A, C > G, C > T, T > A, T > C and T > G) × 16 combinations of bases immediately 5′ and 3′ to each mutation base (context information), and the frequency of each mutation category per sample was computed [2, 3]. The previously defined 30 mutational signatures were downloaded from COSMIC (http://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cosmic/signatures). Assuming the mutational distribution of a single sample is a linear combination of the known 30 signatures, an iterative method was used that was implemented in a R package deconstructSigs [35] to decompose the mutational signatures (a 96 × 30 matrix) for the observed mutational distribution of each DIPG sample (a 96 × 1 vector). The contributions of each known mutational signature in cases 1 and 3, the radiation-associated DIPG samples, were compared to all other primary cases, which were taken from both diagnosis and autopsy (n = 9).

Statistical analysis

To estimate cumulative incidence of DIPG in survivors of pediatric medulloblastoma, the number of observed cases of DIPG during each observation period was divided by the total number of patients who underwent treatment of medulloblastoma [37]. For estimates of cumulative incidence from single institutions, data was obtained for the time period of January 2000 to December 2015. Survival data were extracted from the IDIPGR. Survival functions were estimated using Kaplan-Meier methods (GraphPad Prism version 7.00). For survival by histone status in primary DIPGs, analysis was limited to the subset of tumors for which the OS and sequencing information were available. Cox proportional hazards regression model was used to investigate the association between radiation exposure or histone status and survival after controlling for potential prognostic factors including age and sex (PROC PHREG in SAS 9.4). Mann Whitney test was performed using GraphPad Prism (version 7.00) to compare mutation and fusion frequency in DIPG in radiated and non-radiated setting.

Results

Twelve patients who developed DIPG after radiation treatment for primary pediatric medulloblastoma were identified. Six of these cases were acquired from the IDIPGR, and six were extracted from literature review, reported primarily in results from medulloblastoma cooperative group trials: COG A9961 (n = 2), HIT’91 (n = 1), HIT-SIOP-PNET4 (n = 1), and CCG 9892 (n = 1) [12, 30, 31, 36, 42, 46]. Within the limits of incomplete follow-up timing and records, the estimated cumulative incidence of DIPG after medulloblastoma ranged from 0.3–3.9% among the involved institutions and reported studies (Table 1). The cumulative incidence of radiation-associated DIPG survivors of the reported trials ranged from 0.3–1.5% with median follow-up of 4.7–10 years, while the estimated cumulative incidences at single institutions ranged from 0.7–3.9%.

Primary Medulloblastoma

Patient characteristics and treatments are described in Table 2. Of patients with known sex and age information (n = 7), six were male, and ages at diagnosis of primary medulloblastoma ranged from 2 to 9 years. For risk stratification of medulloblastoma based on clinical criteria, seven cases were average-risk, three were high-risk, and two were unreported. All cases with known histology (n = 6) showed classic histology (cases 1–6) with subgroup classification into either Group 3 (cases 3 and 4) or Group 4 (cases 1, 5, and 6). Cytogenetics was not performed on case 2, which was classified as Group 3/4 by immunohistochemistry (IHC).

Treatment details are described in Additional file 1: Table S1. All cases underwent surgical resection. Seven cases achieved gross total resection and three cases had partial resections; surgical details were not reported for two cases. All patients received CSI (dose range 18.0–36.0 Gy) with a posterior fossa boost (dose range 19.8–36.0 Gy) for total posterior fossa exposure 53.4–60.0 Gy. Ten cases received chemotherapy, which included a variety of established regimens including cytotoxic and/or targeted therapies, one case declined chemotherapy, and one case lacked chemotherapy details.

Radiation-associated DIPG

Diagnostic and outcome information on DIPG for all cases are described in Table 2. Median time to diagnosis of DIPG after completion of primary medulloblastoma therapy was 7 years (range 2–11 years). DIPG histologic diagnoses were reported for 7 patients and included HGG (n = 3), glioma, grade-unspecified (n = 1), anaplastic astrocytoma (n = 2), and pilocytic astrocytoma (n = 1; case was not reviewed centrally by trial). For cases with tissue (cases 1, 3 and 6), IHC revealed the tumors to be negative for H3K27 M staining and GFAP positive (Fig. 1a, positive and negative control tumor staining in Additional file 1: Figure S1). Additional staining in case 3 revealed retention of H3K27me3 (Fig. 1a), consistent with previous analyses of H3 wild-type DIPG, as tri-methyl is lost in H3K27M-mutant glioma [6]. Treatment for DIPG varied widely. Three patients received focal EBRT, two of whom received oral treatment with histone deacetylase inhibitors (panobinostat, vorinostat) and one of whom received everolimus. Three additional patients received chemotherapeutic agents, with temozolomide being the most common choice. One patient declined treatment, and treatment details were not available for five patients.

Radiation-associated DIPGs define a distinct molecular subtype with poor prognosis. a Immunohistochemistry performed for case 3 showed wild-type status for histone H3 (H3K27M) with retention of H3K27me3, as well as diffuse GFAP expression, which was negative in primary medulloblastoma (not shown). Positive and negative controls are shown in Additional file 1: Figure S1. Insufficient tissue was available for such analysis in cases 1 and 6; however, H3 wild-type status was demonstrated by tumor sequencing in these cases. All scale bars are 50 μm. b OS data for primary DIPG in the IDIPGR (n = 428) was compared via Kaplan-Meier analysis to OS of radiation-associated DIPG cohort (n = 8). OS was significantly less for the radiation-associated DIPG group (p = 0.046). c OS data for primary DIPG patients with both genomic and OS information available (n = 38), as categorized by histone mutational status and compared via Kaplan-Meier analysis to OS of radiation-associated DIPG cohort (n = 8). The radiation-associated DIPG cohort showed the shortest OS in comparison to the two subgroups of primary DIPG with significantly shorter survival compared to H3.3 K27 M mutant (p = 0.038) and H3.1 K27 M mutant (p = 0.024) primary DIPGs

For cases with complete outcome data (n = 8), seven patients died at a median of 8 months after DIPG diagnosis (range 4–17 months), and one patient remains living 5 months after DIPG diagnosis. OS was shorter for radiation-associated DIPG as compared to radiographically-confirmed primary DIPG cases from IDIPGR (n = 428, p = 0.046; Fig. 1b). On multivariate analysis, radiation exposure (hazard ratio 2.87; p = 0.014) and age (hazard ratio 1.00; p = 0.019) were associated significantly with overall survival (Additional file 1: Table S2). Further, the radiation-associated DIPG cohort showed the shortest OS compared to two subgroups of primary DIPG with sequencing information (n = 38), separated by H3 status (vs. H3.3 K27 M mutant, p = 0.038; vs. H3.1 K27 M mutant, p = 0.024; Fig. 1c). On multivariate analysis, radiation exposure (hazard ratio 4.51; p = 0.005) and sex (hazard ratio 2.51; p = 0.016) were associated significantly with overall survival (Additional file 1: Table S2).

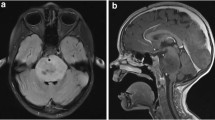

For illustration, case 1 presented with standard-risk medulloblastoma at age 8 (Fig. 2a), and underwent gross total resection (Fig. 3a), followed by 23.4 Gy CSI with a 32.4 Gy boost to primary tumor site (Fig. 2b) with concurrent vincristine. At 21 years of age (12 years after completion of therapy), she presented to her primary care physician with a one-month history of difficulty swallowing and clumsiness of her right hand. MRI brain revealed a new infiltrative mass with diffuse pontine T2 hyperintensity, consistent radiographically with a DIPG (Fig. 2c). MR spectroscopy revealed markedly elevated choline to creatinine peak with depressed NAA peak, consistent with malignancy (Fig. 2d). She underwent re-irradiation and ultimately died of disease 17 months after diagnosis. Histopathology at autopsy revealed a diffusively infiltrating glioma (Fig. 3b). Karyotyping of her initial medulloblastoma previously had revealed isochromosome for the long arm of chromosome 17, a hallmark feature of Group 4 medulloblastoma (Fig. 3c). In contrast, copy number analysis of her DIPG revealed copy number changes frequently seen in gliomas including homozygous loss of RB1, SETDB2, CDKN2A and CDKN2B with no abnormalities in chromosome 17, distinguishing it from the primary medulloblastoma (Fig. 3d-e). Similar imaging findings, radiation fields and MR spectroscopy images were obtained in cases 2 and 3 (Additional file 1: Figures S2 and S3).

Diagnosis and treatment with standard therapy of case 1, which included significant radiation to brainstem. a MR axial T2 FLAIR image of primary medulloblastoma diagnosed at age 8. b Radiation dose distribution showing craniospinal irradiation prescribed to 23.4 Gy and posterior fossa boost prescribed to 32.4 Gy. The brainstem is contoured in purple and received a mean dose of 50.1 Gy. c MR axial T2 FLAIR image of DIPG diagnosed at age 21, 13 years after treatment for primary medulloblastoma and in the area of the previously irradiated field. d MR spectroscopy with an elevated Chol/Cr ratio (1.66) that is consistent with malignancy (DIPG)

Histology and molecular results distinguish primary medulloblastoma from radiation-associated DIPG. a Resected medulloblastoma from case 1 showing characteristic classic-type features including sheets of cells with primitive hyperchromatic nuclei and scant cytoplasm. b DIPG at autopsy showing an infiltrating glial tumor with small angulated nuclei and abundant amphophilic cytoplasm. c Karyotype analysis of medulloblastoma shows near-tetraploid clone with arrow indicating i(17q), most consistent with Group 4. d Copy number analysis of DIPG shows focal and structural changes distinct from primary tumor, including focal homozygous loss of RB1, SETDB2, CDKN2A and CDKN2B, focal 1 copy gain of KIT, KDR and PDGFRA, and activation mutations in NRAS and TP53. e Loss of heterozygosity plot showing regions on chromosomes 6 and 18 with copy-neutral loss of heterozygosity events

DIPG sequencing

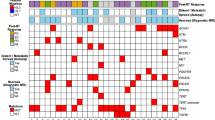

For cases 1, 3, and 6, DIPG frozen tissue from autopsy (cases 1 and 6) and diagnosis (case 3) were sequenced and mutations were analyzed (Additional file 1: Table S3). All three tumors were wild-type for H3F3A and HIST1H3B. Mutational signature analysis of DIPGs showed mutations consistent with radiation-induced DNA damage (e.g., insertional event in TP53), as well as mutations in other oncogenic drivers (e.g., PTEN, EGFR, and NRAS), suggestive of a distinct mutational process as compared with primary DIPGs. Mutations identified in radiation-associated DIPGs had molecular overlap with recurrent drivers of adult GBM, using previously published datasets of adult GBM and primary DIPG (Fig. 4a) [7, 44]. Within a cohort sequenced using the same sequencing methodology (UM MI-ONCOSEQ) (n = 11), COSMIC mutational signature analysis demonstrated that radiation-associated DIPGs had the highest predicted somatic mutation counts and were more likely to harbor Signature 24 than primary DIPGs, which has not previously been connected to previous malignancy or radiation exposure (Fig. 4b) [3]. Cases with previous radiation in the MI-ONCOSEQ cohort (including cases 1 and 3 form this series as well as primary DIPG cases at autopsy) harbored higher mutations (Fig. 4c; p = 0.0043) and fusions per exome (Fig. 4d; p = 0.0135), although overall mutational burden remained lower than what might be clinically significant in comparison to cancers with known mismatch repair deficiency [22]. Cases 1 and 3 underwent germline sequencing as well, which revealed no evidence of cancer predisposition syndromes.

Radiation-associated DIPGs are molecularly distinct from primary DIPGs. a Plot of recurrent mutations in previously published datasets (adult GBM [n = 500] [7]; primary DIPG [n = 55] [44]) demonstrates that the distribution of driving mutations in radiation-associated DIPG is more similar to recurrent alterations in adult GBM than primary DIPG. b Contributions of established COSMIC mutational signatures were determined for radiation-associated DIPG samples as compared to all other primary cases sequenced through same sequencing platform (MI-ONCOSEQ). c-d Cases with previous radiation in this cohort (including case 1 and 3 and primary DIPG at autopsy) show higher mutations and fusions per exome (p = 0.0043 and p = 0.0135, respectively using Mann Whitney test)

Discussion

With cumulative incidences ranging from 4.2–12%, long-term survivors of medulloblastoma show an increased risk of central nervous system SMNs, particularly gliomas [15, 19, 29, 31, 39, 42]. The risk of glioma has been shown to increase linearly with radiation dose, with reported excess relative risk of 0.079–0.33 per Gy [4, 38]. Prior studies have commented on radiation-associated DIPG following individual cases of pediatric central nervous system cancers [1, 8, 9, 17], although no studies have commented specifically on the incidence or molecular characteristics of radiation-associated DIPGs following treatment for pediatric medulloblastoma. In standard medulloblastoma therapy, the brainstem receives high doses of EBRT due to its anatomic proximity to the posterior fossa boost. In this study, the estimated cumulative incidence of DIPG in children diagnosed with medulloblastoma and treated with EBRT ranged from 0.3–3.9%. The cumulative incidence reported in this study may have been impacted by incomplete or brief follow-up and may be underestimated as the cohort continues to age. While DIPG was diagnosed at a median of 7 years after completion of treatment for medulloblastoma, median follow-up was only 10 years or less for the cited studies. In large studies of pediatric survivors, median time to diagnosis of radiation-associated gliomas ranged from 6.6–17.4 years [9, 15, 28, 32, 38, 39]. Furthermore, in patients with treated primary medulloblastoma, posterior fossa tumors often are labeled as recurrent medulloblastomas based solely on radiographic evidence. It may be that some tumors that are not biopsied and assumed to be recurrent medulloblastomas may in fact be DIPGs.

Increasing attention has been given to the impact of radiation field and modality on efficacy and risk of SMNs. For medulloblastoma treatment, many centers now are shifting away from a posterior fossa boost and toward a primary site boost only [24, 43]. Preliminary results from a recently closed phase III COG trial (ACNS0331) of involved field radiotherapy with chemotherapy in average-risk medulloblastoma found no difference in 5-year event free survival or OS when boost volume was limited to the primary site vs. entire posterior fossa [25]. In patients treated with primary site boost only, proton radiotherapy may decrease brainstem radiation exposure even further relative to photon therapy [11, 34]. In a multi-institutional cohort study and phase II single center trial, there were no significant differences in recurrence-free survival or OS between patients treated with photon vs. proton radiotherapy, and in the phase II trial, no radiation-associated malignancies were reported within a median follow-up time of 7 years [45]. While longer follow-up is required to evaluate definitively its impact, smaller boost fields and proton radiotherapy show promise for reducing the risk of SMNs without sacrificing efficacy of treatment.

Radiation-associated gliomas are molecularly distinct from their primary counterparts. A previous report of non-brainstem radiation-associated pediatric GBM showed overexpression of a number of genes involved in tumorigenesis as compared to primary pediatric GBM [13]. Additionally, prior studies suggest that tumors can be differentiated based on these molecular signatures and that radiation-associated tumors may exhibit distinct patterns [3, 5]. It has been observed that radiation-associated tumors exhibit a significantly higher total number of mutations, as well as balanced inversions, with both small deletions and inversions generating driver mutations [5].

In this study, tumor exome sequencing of three radiation-associated DIPGs demonstrated tumors to be H3-wildtype. This finding is significant in the context of a recent large cohort of sequenced primary DIPGs, in which only 16.8% were found to be H3-wildtype [23]. Notably, sequencing confirmed that the tumors were indeed distinct from their primary malignancies and not local recurrences. Moreover, patients did not harbor germline mutations in known cancer predisposition genes. Although alterations in two of the most frequently mutated genes in primary DIPG (H3F3A and ACVR1) were not detected, the tumor mutations in the sequenced cases are established tumor drivers in adult GBM (e.g. PTEN, NRAS, and EGFR). Interestingly, case 3 was found to have an EZH2 mutation in the radiation-associated DIPG, which has not been identified as a recurrent driver in DIPG, but has been established as a potential therapeutic target in pre-clinical DIPG models [27]. Mutational signature analysis of radiation-associated DIPGs showed mutations consistent with radiation-induced DNA damage (e.g., insertional event in TP53), at a rate similar to cases observed in a recent report of radiation-associated GBMs, in which two out of five sequenced GBMs had mutations in TP53 [33]. Unlike radiation-associated GBMs, however, PDGFRA played a smaller role in the cohort of radiation-associated DIPG. The PDGFRA amplification in case 1 (Fig. 1d) was the isolated alteration in the three tumors. While non-silent mutations in PDGFRA were identified in all five radiation-associated GBMs, none of radiation-associated DIPGs from this study had mutations in PDGFRA.

Taken together, these results are suggestive of distinct mutational processes compared with primary DIPGs: primary DIPGs originate within a particular early developmental timespan that is amenable to transformation with H3F3A and ACVR1 mutation [23], whereas radiation-associated DIPGs appear to arise as a result of radiation-induced DNA damage in established oncogenic drivers of primary adult GBM. Future sequencing of additional cases may elucidate patterns of distinct biology in radiation-associated DIPG, which may have implications in terms of clinical management. These data suggest that patients with radiation-associated DIPG may benefit from future therapies targeted to the molecular features of adult GBM rather than primary DIPG.

Significantly, the radiation-associated DIPG cohort demonstrated a shorter OS relative to patients with primary DIPG. The three molecularly sequenced cases of radiation-associated DIPG cohort additionally are distinguished as H3 wild-type designation, considered a positive prognostic variable in primary DIPG relative to H3.3 mutant DIPG [10, 20]. Prior studies report a similar decreased survival from radiation-induced HGG as compared to primary HGG [13, 21]. In conjunction with the molecular findings, these data suggest that radiation-associated DIPGs form a distinct molecular subgroup that has negative implications on survival. The findings in this work demonstrate the importance of tumor biopsy or resection at appearance of a second cancer. Most cases had no or limited histological and molecular diagnostic information, which was not clinically relevant until recently. Now, this information is critical for prognostic information, current clinical management, and potential future therapies [33].

Conclusions

In conclusion, patients treated for pediatric medulloblastoma are at increased risk for development of radiation-associated DIPG, which may represent a distinct molecular subtype with a worse prognosis relative to other DIPGs. This risk highlights the importance of radiation volume and modality in the treatment of children with medulloblastoma and provides a compelling argument for efforts to reduce exposure of the brainstem. Additionally, the presented molecular data suggest that patients with radiation-associated DIPG may benefit from future therapies targeted to the molecular features of adult GBM rather than primary DIPG.

References

Abboud SE, Wolansky LJ, Manjila SV, Lo SS, Arafah BM, Selman WR, Couce ME, Rogers LR (2015) Histologically proven radiation-induced brainstem Glioma 93 months after external beam radiotherapy for pituitary macroadenoma: radiation treatment dose and volume correlation. J Neuroimaging 25:674–676. https://doi.org/10.1111/jon.12181

Alexandrov LB, Jones PH, Wedge DC, Sale JE, Campbell PJ, Nik-Zainal S, Stratton MR (2015) Clock-like mutational processes in human somatic cells. Nat Genet 47:1402–1407. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3441

Alexandrov LB, Nik-Zainal S, Wedge DC, Aparicio SA, Behjati S, Biankin AV, Bignell GR, Bolli N, Borg A, Borresen-Dale AL et al (2013) Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature 500:415–421. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12477

Armstrong GT, Stovall M, Robison LL (2010) Long-term effects of radiation exposure among adult survivors of childhood cancer: results from the childhood cancer survivor study. Radiat Res 174:840–850. https://doi.org/10.1667/RR1903.1

Behjati S, Gundem G, Wedge DC, Roberts ND, Tarpey PS, Cooke SL, Van Loo P, Alexandrov LB, Ramakrishna M, Davies H, et al (2016) Mutational signatures of ionizing radiation in second malignancies. Nat Commun 7: 12605 https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms12605

Bender S, Tang Y, Lindroth AM, Hovestadt V, Jones DT, Kool M, Zapatka M, Northcott PA, Sturm D, Wang W et al (2013) Reduced H3K27me3 and DNA hypomethylation are major drivers of Gene Expr in K27M mutant pediatric high-grade gliomas. Cancer Cell 24:660–672. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccr.2013.10.006

Brennan CW, Verhaak RG, McKenna A, Campos B, Noushmehr H, Salama SR, Zheng S, Chakravarty D, Sanborn JZ, Berman SH et al (2013) The somatic genomic landscape of glioblastoma. Cell 155:462–477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.034

Broniscer A, Baker JN, Baker SJ, Chi SN, Geyer JR, Morris EB, Gajjar A (2010) Prospective collection of tissue samples at autopsy in children with diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma. Cancer 116:4632–4637. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.25405

Broniscer A, Ke W, Fuller CE, Wu J, Gajjar A, Kun LE (2004) Second neoplasms in pediatric patients with primary central nervous system tumors: the St. Jude Children's Research Hospital experience. Cancer 100:2246–2252. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.20253

Castel D, Philippe C, Calmon R, Le Dret L, Truffaux N, Boddaert N, Pages M, Taylor KR, Saulnier P, Lacroix L et al (2015) Histone H3F3A and HIST1H3B K27M mutations define two subgroups of diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas with different prognosis and phenotypes. Acta Neuropathol 130:815–827. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-015-1478-0

Chung CS, Yock TI, Nelson K, Xu Y, Keating NL, Tarbell NJ (2013) Incidence of second malignancies among patients treated with proton versus photon radiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 87:46–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2013.04.030

Cooney T, Lane A, Bartels U, Bouffet E, Goldman S, Leary SES, Foreman NK, Packer RJ, Broniscer A, Minturn JE et al (2017) Contemporary survival endpoints: an international diffuse intrinsic Pontine Glioma registry study. Neuro Oncol 19:1279–1280. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/nox107

Donson AM, Erwin NS, Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Madden JR, Addo-Yobo SO, Foreman NK (2007) Unique molecular characteristics of radiation-induced glioblastoma. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 66:740–749. https://doi.org/10.1097/nen.0b013e3181257190

Fossati P, Ricardi U, Orecchia R (2009) Pediatric medulloblastoma: toxicity of current treatment and potential role of protontherapy. Cancer Treat Rev 35:79–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctrv.2008.09.002

Friedman DL, Whitton J, Leisenring W, Mertens AC, Hammond S, Stovall M, Donaldson SS, Meadows AT, Robison LL, Neglia JP (2010) Subsequent neoplasms in 5-year survivors of childhood cancer: the childhood Cancer survivor study. J Natl Cancer Inst 102:1083–1095. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djq238

Fu W, O'Connor TD, Jun G, Kang HM, Abecasis G, Leal SM, Gabriel S, Rieder MJ, Altshuler D, Shendure J et al (2013) Analysis of 6,515 exomes reveals the recent origin of most human protein-coding variants. Nature 493:216–220. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11690

Fuller GN, Kaba SE, Ginsberg LE, McCutcheon IE, Langford LA (1997) Late sequelae of treated pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma: malignant brain stem astrocytoma occurring 15 years after radiation therapy. J Neuro-Oncol 32:57–61

Genomes Project C, Abecasis GR, Altshuler D, Auton A, Brooks LD, Durbin RM, Gibbs RA, Hurles ME, McVean GA (2010) A map of human genome variation from population-scale sequencing. Nature 467:1061–1073. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature09534

Goldstein AM, Yuen J, Tucker MA (1997) Second cancers after medulloblastoma: population-based results from the United States and Sweden. Cancer Causes Control 8:865–871

Hoffman LM, Veldhuijzen van Zanten SEM, Colditz N, Baugh J, Chaney B, Hoffmann M, Lane A, Fuller C, Miles L, Hawkins C et al (2018) Clinical, radiologic, pathologic, and molecular characteristics of long-term survivors of diffuse intrinsic Pontine Glioma (DIPG): a collaborative report from the international and European Society for Pediatric Oncology DIPG registries. J Clin Oncol 36:1963–1972. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2017.75.9308

Kleinschmidt-Demasters BK, Kang JS, Lillehei KO (2006) The burden of radiation-induced central nervous system tumors: a single institution s experience. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 65:204–216. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.jnen.0000205146.62081.29

Le DT, Durham JN, Smith KN, Wang H, Bartlett BR, Aulakh LK, Lu S, Kemberling H, Wilt C, Luber BS et al (2017) Mismatch repair deficiency predicts response of solid tumors to PD-1 blockade. Sci 357:409–413. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aan6733

Mackay A, Burford A, Carvalho D, Izquierdo E, Fazal-Salom J, Taylor KR, Bjerke L, Clarke M, Vinci M, Nandhabalan M et al (2017) Integrated Molecular Meta-Analysis of 1,000 Pediatric High-Grade and Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma. Cancer Cell 32:520–537. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccell.2017.08.017 e525

Merchant TE, Kun LE, Krasin MJ, Wallace D, Chintagumpala MM, Woo SY, Ashley DM, Sexton M, Kellie SJ, Ahern V et al (2008) Multi-institution prospective trial of reduced-dose craniospinal irradiation (23.4 Gy) followed by conformal posterior fossa (36 Gy) and primary site irradiation (55.8 Gy) and dose-intensive chemotherapy for average-risk medulloblastoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 70:782–787. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.07.2342

Michalski JM, Janss A, Vezina G, Gajjar A, Pollack I, Merchant TE, FitzGerald TJ, Booth T, Tarbell NJ, Li Y et al (2016) Results of COG ACNS0331: a phase III trial of involved-field radiotherapy (IFRT) and low dose Craniospinal irradiation (LD-CSI) with chemotherapy in average-risk Medulloblastoma: a report from the Children's oncology group. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 96:937–938

Mody RJ, Wu YM, Lonigro RJ, Cao X, Roychowdhury S, Vats P, Frank KM, Prensner JR, Asangani I, Palanisamy N et al (2015) Integrative Clinical Sequencing in the Management of Refractory or Relapsed Cancer in Youth. Jama 314:913–925. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.10080

Mohammad F, Weissmann S, Leblanc B, Pandey DP, Hojfeldt JW, Comet I, Zheng C, Johansen JV, Rapin N, Porse BT et al (2017) EZH2 is a potential therapeutic target for H3K27M-mutant pediatric gliomas. Nat Med 23:483–492. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.4293

Neglia JP, Robison LL, Stovall M, Liu Y, Packer RJ, Hammond S, Yasui Y, Kasper CE, Mertens AC, Donaldson SS et al (2006) New primary neoplasms of the central nervous system in survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the childhood Cancer survivor study. J Natl Cancer Inst 98:1528–1537. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djj411

Ning MS, Perkins SM, Dewees T, Shinohara ET (2015) Evidence of high mortality in long term survivors of childhood medulloblastoma. J Neuro-Oncol 122:321–327. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-014-1712-y

Packer RJ, Goldwein J, Nicholson HS, Vezina LG, Allen JC, Ris MD, Muraszko K, Rorke LB, Wara WM, Cohen BH et al (1999) Treatment of children with medulloblastomas with reduced-dose craniospinal radiation therapy and adjuvant chemotherapy: A Children's Cancer Group Study. J Clin Oncol 17:2127–2136. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.1999.17.7.2127

Packer RJ, Zhou T, Holmes E, Vezina G, Gajjar A (2013) Survival and secondary tumors in children with medulloblastoma receiving radiotherapy and adjuvant chemotherapy: results of Children's oncology group trial A9961. Neuro-Oncology 15:97–103. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/nos267

Pettorini BL, Park YS, Caldarelli M, Massimi L, Tamburrini G, Di Rocco C (2008) Radiation-induced brain tumours after central nervous system irradiation in childhood: a review. Childs Nerv Syst 24:793–805. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-008-0631-7

Phi JH, Park AK, Lee S, Choi SA, Baek IP, Kim P, Kim EH, Park HC, Kim BC, Bhak J et al (2018) Genomic analysis reveals secondary glioblastoma after radiotherapy in a subset of recurrent medulloblastomas. Acta Neuropathol 35(6):939–953. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-018-1845-8

Rechner LA, Howell RM, Zhang R, Newhauser WD (2012) Impact of margin size on the predicted risk of radiogenic second cancers following proton arc therapy and volumetric modulated arc therapy for prostate cancer. Phys Med Biol 57:N469–N479. https://doi.org/10.1088/0031-9155/57/23/N469

Rosenthal R, McGranahan N, Herrero J, Taylor BS, Swanton C (2016) DeconstructSigs: delineating mutational processes in single tumors distinguishes DNA repair deficiencies and patterns of carcinoma evolution. Genome Biol 17:31. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-016-0893-4

Sabel M, Fleischhack G, Tippelt S, Gustafsson G, Doz F, Kortmann R, Massimino M, Navajas A, von Hoff K, Rutkowski S et al (2016) Relapse patterns and outcome after relapse in standard risk medulloblastoma: a report from the HIT-SIOP-PNET4 study. J Neurooncol 129:515–524. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-016-2202-1

Stromberg U (1994) A distinction between cumulative incidence and risk as measures of disease occurrence. Int J Epidemiol 23:1104–1105

Taylor AJ, Little MP, Winter DL, Sugden E, Ellison DW, Stiller CA, Stovall M, Frobisher C, Lancashire ER, Reulen RC et al (2010) Population-based risks of CNS tumors in survivors of childhood cancer: the British Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol 28:5287–5293. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2009.27.0090

Tsui K, Gajjar A, Li C, Srivastava D, Broniscer A, Wetmore C, Kun LE, Merchant TE, Ellison DW, Orr BA et al (2015) Subsequent neoplasms in survivors of childhood central nervous system tumors: risk after modern multimodal therapy. Neuro Oncol 17:448–456. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/nou279

Venneti S, Garimella MT, Sullivan LM, Martinez D, Huse JT, Heguy A, Santi M, Thompson CB, Judkins AR (2013) Evaluation of histone 3 lysine 27 trimethylation (H3K27me3) and enhancer of zest 2 (EZH2) in pediatric glial and glioneuronal tumors shows decreased H3K27me3 in H3F3A K27M mutant glioblastomas. Brain Pathol 23:558–564. https://doi.org/10.1111/bpa.12042

Venneti S, Santi M, Felicella MM, Yarilin D, Phillips JJ, Sullivan LM, Martinez D, Perry A, Lewis PW, Thompson CB et al (2014) A sensitive and specific histopathologic prognostic marker for H3F3A K27M mutant pediatric glioblastomas. Acta Neuropathol 128:743–753. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-014-1338-3

von Hoff K, Hinkes B, Gerber NU, Deinlein F, Mittler U, Urban C, Benesch M, Warmuth-Metz M, Soerensen N, Zwiener I et al (2009) Long-term outcome and clinical prognostic factors in children with medulloblastoma treated in the prospective randomised multicentre trial HIT'91. Eur J Cancer 45:1209–1217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2009.01.015

Wolden SL, Dunkel IJ, Souweidane MM, Happersett L, Khakoo Y, Schupak K, Lyden D, Leibel SA (2003) Patterns of failure using a conformal radiation therapy tumor bed boost for medulloblastoma. J Clin Oncol 21:3079–3083. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2003.11.140

Wu G, Diaz AK, Paugh BS, Rankin SL, Ju B, Li Y, Zhu X, Qu C, Chen X, Zhang J et al (2014) The genomic landscape of diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma and pediatric non-brainstem high-grade glioma. Nat Genet 46:444–450. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.2938

Yock TI, Yeap BY, Ebb DH, Weyman E, Eaton BR, Sherry NA, Jones RM, MacDonald SM, Pulsifer MB, Lavally B et al (2016) Long-term toxic effects of proton radiotherapy for paediatric medulloblastoma: a phase 2 single-arm study. Lancet Oncol 17:287–298. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00167-9

You SH, Lyu CJ, Kim DS, Suh CO (2013) Second primary brain tumors following cranial irradiation for pediatric solid brain tumors. Childs Nerv Syst 29:1865–1870. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-013-2098-4

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge all patients and their families who have supported and contributed to the International DIPG Registry. Supporting foundations include: The Cure Starts Now Foundation, Hope for Caroline Foundation, Julian Boivin Courage for Cures Foundation, Abbie’s Army, Michael Mosier Defeat DIPG Foundation, Reflections of Grace Foundation, The Cure Starts Now Australia, Brooke Healey Foundation, Soar With Grace Foundation, Jeffrey Thomas Hayden Foundation, Cure Brain Cancer Foundation, The Jones Family Foundation, Musella Foundation, Pray, Hope Believe Foundation, Smiles for Sophie Foundation, Benny’s World, Love Chloe Foundation, Aiden’s Avengers, A Cure from Caleb Society, The Operation Grace White Foundation, Ryan’s Hope, Wayland Villars DIPG Foundation, American Childhood Cancer Organization, Juliana Rose Donnelly Trust, Sheila Jones & Friends, The Ellie Kavalieros DIPG Research Fund, Voices Against Brain Cancer, The DIPG Collaborative.

Funding

CK is supported by NIH/NINDS Grant K08-NS099427–01, Michigan Medicine Department of Pediatrics Gorman Scholar Award, The University of Michigan Chad Carr Pediatric Brain Tumor Center, the Chad Tough Foundation and Hyundai Hope on Wheels. NGG is supported by a Cancer Council of Western Australia fellowship.

Availability of data and materials

Data is available through the International DIPG Registry or published literature.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have contributed meaningfully to the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All patients have consented to participate or case data were extracted from literature review.

Consent for publication

All authors consent to publication of this work.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Table S1. Treatment details for primary medulloblastoma. Table S2. Multivariate analysis of overall survival for primary and radiation-associated DIPGs. Table S3. Sequencing of radiation-associated DIPGs. Figure S1. Immunohistochemical staining for H3K27 M of positive and negative control pediatric high-grade gliomas. Figure S2. Diagnosis and management of case 2, which included non-standard treatment for medulloblastoma. Figure S3. Diagnosis and management of case 3, which included standard therapy for medulloblastoma. (DOCX 5366 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Gits, H.C., Anderson, M., Stallard, S. et al. Medulloblastoma therapy generates risk of a poorly-prognostic H3 wild-type subgroup of diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma: a report from the International DIPG Registry. acta neuropathol commun 6, 67 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40478-018-0570-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40478-018-0570-9