Abstract

Background

Osteogenesis imperfecta (OI) is a rare bone disorder. In 90% of cases, OI is caused by mutations in the COL1A1/2 genes, which code procollagen α1 and α2 chains. The main aim of the current research was to identify the mutational spectrum of COL1A1/2 genes in Estonian patients. The small population size of Estonia provides a unique chance to explore the collagen I mutational profile of 100% of OI families in the country.

Methods

We performed mutational analysis of peripheral blood gDNA of 30 unrelated Estonian OI patients using Sanger sequencing of COL1A1 and COL1A2 genes, including all intron-exon junctions and 5′UTR and 3′UTR regions, to identify causative OI mutations.

Results

We identified COL1A1/2 mutations in 86.67% of patients (26/30). 76.92% of discovered mutations were located in the COL1A1 (n = 20) and 23.08% in the COL1A2 (n = 6) gene. Half of the COL1A1/2 mutations appeared to be novel. The percentage of quantitative COL1A1/2 mutations was 69.23%. Glycine substitution with serine was the most prevalent among missense mutations. All qualitative mutations were situated in the chain domain of pro-α1/2 chains.

Conclusion

Our study shows that among the Estonian OI population, the range of collagen I mutations is quite high, which agrees with other described OI cohorts of Northern Europe. The Estonian OI cohort differs due to the high number of quantitative variants and simple missense variants, which are mostly Gly to Ser substitutions and do not extend the chain domain of COL1A1/2 products.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Despite being a rare genetic bone fragility disorder, osteogenesis imperfecta (OI) is among the most widely occurring of rare congenital skeletal dysplasias [1]. OI prevalence is estimated 1/10,000–20,000 at birth [2, 3]. OI is characterized by low bone mineral density, recurrent fractures, skeletal deformations, and blue eye sclera [2, 4,5,6]. Other remarkable features of OI include Dentinogenesis Imperfecta, triangular face, hearing loss, joint laxity, short stature, and easy bruising [2, 4,5,6].

OI has many manifestations and is considered a group of disorders. Phenotypes range from mild osteopenia to severe deformities or even mortality. In 1979, Sillence described four OI types (I–IV) according to phenotype severity [5]. Recent updated classification distinguishes three additional types with specific histologies (V–VII) [4, 7]. Genetic OI classification considers every OI gene as a separate OI type and so far includes OI types I–XVII [4, 8, 9].

The genetics of the disorder reflect the complexity of the OI phenotype range. Up to 21 different genes have been associated with occurrence of OI [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. Previous studies have shown that the primary cause of OI are mutations in the COL1A1/2 genes, which code procollagen type I α1 and α2 chains, respectively [20]. Despite the approximately 1500 mutations already described in collagen type I genes, investigators continue to report novel mutations [21]. Moreover, there is still some controversy regarding the proportion of collagen mutations reported in different populations, which have ranged from 60 to 95% [9, 10]. In this context, we believe that population-based studies of OI genetics might broaden current knowledge of collagen I mutations and OI.

Due to Estonia’s small population (1.3 million) and centered treatment, follow-up, and research of all OI patients at the OI Center of the Traumatology and Orthopedics Clinic, Tartu University (TU) Hospital, it was possible to perform analysis of COL1A1/2 mutations among the whole Estonian OI population [22]. Herein, we describe for the first time the mutational spectrum of COL1A1/2 genes among 30 unrelated OI patients, from 30 Estonian OI families, which we estimate to constitute ~ 100% of OI cases in Estonia.

Methods

Subjects

The patients included in the study are treated and followed-up by the OI Center of the Traumatology and Orthopedics Clinic, TU Hospital.

A total of 30 OI patients from 30 unrelated families were included in the study. Data regarding the OI types of the subjects were obtained from the medical records of TU Hospital [23]. All new OI cases across Estonia are registered by and treated at TU Hospital’s OI Center. Thus, it can be estimated that as of May 2017, the current patient cohort represented ~ 100% of the Estonian OI population.

No patient came from a consanguineous family. Mutational analysis of the COL1A1/2 genes was performed on a younger affected member of every OI family included in the study.

In accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, all patients or their legal representatives signed an informed consent form prior to participation. The study was approved by the University of Tartu’s Ethical Review Committee on Human Research (permit no. 221/M-34).

Genealogical description

Genealogical data of OI history in the family, consanguinity, and miscarriages was obtained from each patient or their representative. We constructed pedigree trees per kindred using the “Kinship2” package in R v3.3.2 [24].

Mutational analysis of the COL1A1/2 genes

Genomic DNA (gDNA) was purified from 3 ml of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) preserved whole blood samples—stored at −80 °C—using a Gentra Puregene Blood Kit (Quiagen, Germany) following the manufacturer’s protocol.

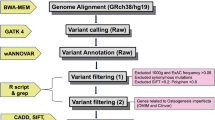

PCR amplification and Sanger sequencing were performed as described previously [25]. Sequence products were analyzed using Applied Biosystems’ Sequence Scanner v1.0 and Mutation Surveyor DNA Variant analysis software v5.0.1. (Softgenetics, USA) and aligned to the GenBank human reference genome sequences of COL1A1 (gDNA NG_007400.1, complementary (cDNA) NM_000088.3), and COL1A2 (gDNA NG_007405.1, cDNA NM_000089.3). Raw sequencing data are available from the authors upon request. We focused on non-synonymous and splice-site variants absent from the publicly available normal datasets (including dbSNP135 and the 1000 Genomes Project) [26, 27]. We used the PolyPhen-2, SIFT, and MutationTaster software tools to predict the functional effects and pathogenicity of mutations [28,29,30]. Variants absent from the osteogenesis imperfecta mutation database were considered novel (http://www.le.ac.uk/ge/collagen/) [21, 31].

All statistical analyses were carried out with R v3.3.2. software (R Team, Austria) [32]. To assess the distribution of COL1A1/2 mutations and compare them to other studied OI populations, percentage differences were used.

Results

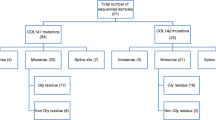

Mutational analysis of the COL1A1/2 genes of Estonian OI patients highlighted OI causative mutations in 26 of 30 patients (86.67%) (Fig. 1a). The number of patients harboring COL1A1 mutations was 20 (76.92%); COL1A2 mutations were found in 6 patients (23.08%) (Fig. 1b). A list of the mutations and their characteristics can be found in Table 1.

The number of novel mutations was 13/26 (50%) (Table 1). Half of the COL1A1 and COL1A2 mutations appeared to be undescribed in the collagen type I mutation database. Patient EE26 had a heterozygous non-synonymous rs1800215 SNP (p.Ala1075Thr) in the COL1A1 gene, which was described before as a benign variant (data not shown). [33]

Twenty-five mutations had an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern (Table 1). Of these, eight patients had no previous history of OI in the family. Thus, we assumed that their parents and relatives, who did not have any clinical features of OI, are not carriers of these mutations.

Patient EE07 had a recessive missense mutation. Mutational analysis showed that their parents are not carriers of the mutation, which confirmed the de novo nature of the mutation.

We found 12/26 mutations (46.15%) had altering splice sites, 10 and 2 in the COL1A1 and COL1A2 genes, respectively. One of the patients harbored a deletion capturing both coding and intronic sequence, in exon-intron 34 (EE30). Nonsense mutations were present in 6 patients (23.08%), all in the COL1A1 gene. Overall, quantitative mutations were present in 18 patients (16 in COL1A1 and 2 in COL1A2 genes) (Fig. 2).

Missense mutations, associated with collagen I quality defects, were indicated in eight patients (30.77%), four in COL1A1 and four in COL1A2 genes. Of these, seven were Glycine substitutions (four of the COL1A2 and three of the COL1A1 missense mutations). In four cases, Glycine was substituted with Serine, two in the COL1A1 and COL1A2 genes, respectively (Fig. 2).

A c.3262G>T (COL1A1) mutation was detected in two patients (EE21 and EE22), who were thought to be unrelated (Table 1). Investigation of the pedigree trees revealed a distant relationship between the families four generations back, of which the patients were not aware. Two identical splice site mutations at c.1821 + 1G>A (COL1A1) in intron 26 were identified in patients EE02 (type III OI) and EE05 (type I OI) (Table 1). This mutation arose independently in the patients and caused phenotypes of different severity.

Discussion

Collagen I mutations were found in 26/30 (87%) studied OI patients. Previous findings have suggested collagen mutations ranging from 60 to 90% among different OI populations and study cohorts [25]. In a Finnish OI study, 90.7% of patients harbored collagen I mutations [34], which is higher than we found among Estonian OI patients. In Pollitt et al.’s study, collagen I mutations were revealed in 75% of OI patients [35], which is slightly lower than our Estonian cohort. Our data is in good agreement with research on the genetic epidemiology of the Swedish OI population, of which 87% had collagen I mutations [36]. The results of our study are also in concordance with Bardai et al.’s recent study of a large number (598) of OI individuals, where collagen type I mutations were found in 86% of OI patients of all types and different ethnic groups [19].

In some population studies, the amount of collagen I mutations were also lower. For example, in 51.4% of Taiwanese patients (N = 72), 52.2% of Korean patients (N = 67), and 59.4% of Vietnamese OI patients (N = 91) [25, 37, 38]. Due to the difficulties in arranging large cross-population studies of a rare disorder in populous countries, results can often be fragmented, which complicates population-wide estimates [39, 40]. However, questions about the lower collagen type I mutational pattern of OI patients from Asian populations remain.

The proportions of COL1A1 and COL1A2 in Estonian, Finnish, and Swedish OI populations were surprisingly similar, 77 and 23%, 78 and 22%, and 79 and 21%, respectively [34, 36]. Similar values were reported by Pollitt et al., where 77% of mutations occurred in the COL1A1 and 23% in the COL1A2 gene (N = 83) [35]. In Bardai et al.’s 2016 study, 69% were COL1A1 and 31% COL1A2 mutations, which is similar to the beforementioned results [19].

The Estonian cohort also has a high proportion of quantitative mutations compared to qualitative collagen mutations, 69 and 31%, respectively. In the Finnish OI cohort, 67% of mutations were quantitative and 33% qualitative [34]. In the work of Pollitt et al., 35% of mutations were qualitative and 65% quantitative [35]. In the Swedish population, the proportions were almost equal (53 and 47%) [36]. Interestingly, we found only two quantitative mutations in the COL1A2 gene, which matches previous reports about comparatively lower numbers of quantitative mutations of this gene [34,35,36]. Due to the higher number of mutations leading to haploinsufficiency in the COL1A1 gene compared to the COL1A2 gene, patients harboring mutations in the COL1A1 gene had milder phenotypes (I, IV) compared to patients with COL1A2 mutations (type III, except EE20 who had a splice site mutation and OI type I).

Glycine substitutions composed the vast majority of missense mutations (7 of 8 cases), with serine being the most substituted amino acid (4 of 7 cases), which supports previous findings. Curiously, all missense mutations were situated in triple helical chain domains (aa residues 162–1218 α1; aa residues 80–1102 α2) of COL1A1/2 gene products. Only one mutation (patient EE07 with OI type II) altered the “lethal cluster” proposed by Marini et al. [41].

Half of the mutations (50%) we found appeared to be novel. Despite the numerous works on collagen I mutations and a growing list of identified mutations, the number of revealed novel variants was high, which underlines the individual nature of OI mutations [19, 35, 36]. Half of the glycine substitutions (4 of 7) were even absent from the collagen I mutational database.

Despite sharing of the same mutation, patients may develop different phenotypes, as in the case of patients EE02 and EE05, who had type III and I OI, respectively. Genotype-phenotype correlations remain an unresolved issue in our understanding of OI. Cases of inter- and intra-familial OI diversity are not rare. Not only genetics, but additional factors, such as epigenetics and environment might contribute to the development of specific OI phenotypes. This leads to many questions and the need to further investigate potential OI factors.

Sanger sequencing is a powerful and accurate method of mutational analysis and allows the identification of frameshift, and missense and nonsense mutations in the coding regions of genes. Moreover, due to the special design of the primers distant from intron-exon junction regions, we could asses splice site mutations of the COL1A1/2 genes, which are the cause of quantitative collagen defects. However, the current study had some limitations. We could not identify whole gene or exon deletions and duplications, which could have slightly reduced the number of discovered COL1A1/2 mutations. In addition, due to the small population size of Estonia, our cohort was limited. We cannot exclude the possibility that the small sample size might be the cause of differences compared to the results of other studies.

Conclusion

This paper has described the mutational spectrum of COL1A1/2 genes among 30 Estonian OI patients, which were estimated to represent ~ 100% of OI families in Estonia at the time. We identified collagen I mutations in 87% of Estonian OI families. The number of quantitative mutations (69%) was high compared to other European OI cohorts. All missense mutations of our Estonian patients altered the triple helical chain domain of α1 and α2 procollagen chains. One mutation was situated in the lethal cluster. A normal distribution of novel collagen mutations (50%) among the COL1A1 (77%) and COL1A2 (23%) genes, and mostly glycine substitutions were observed, compared to other OI cohorts of Northern Europe. Four patients that showed no collagen type I mutations will be further studied using whole exome sequencing analysis to identify disease causing variants.

Abbreviations

- 3’UTR:

-

Three prime untranslated region

- 5’UTR:

-

Five prime untranslated region

- cDNA:

-

Complementary DNA

- EDTA:

-

Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- gDNA:

-

Genomic DNA

- OI:

-

Osteogenesis Imperfecta

- TU:

-

University of Tartu

References

Martin E, Shapiro JR. Osteogenesis imperfecta: epidemiology and pathophysiology. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2009;5(3):91–7. doi:10.1007/s11914-007-0023-z.

Byers PH, Steiner RD. Osteogenesis imperfecta. Annu Rev Med. 1992;43:269–82. doi:10.1146/annurev.me.43.020192.001413.

Martin E, Shapiro JR. Osteogenesis imperfecta: epidemiology and pathophysiology. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2007;5(3):91–7. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17925189. Accessed 5 Apr 2017

Van Dijk FS, Sillence DO. Osteogenesis imperfecta: clinical diagnosis, nomenclature and severity assessment. Am J Med Genet A. 2014;164A(6):1470–81. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.36545.

Sillence DO, Senn A, Danks DM. Genetic heterogeneity in osteogenesis imperfecta. J Med Genet. 1979;16(2):101–16. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=1012733&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. Accessed 18 Sept 2014

Ben Amor M, Rauch F, Monti E, Antoniazzi F. Osteogenesis imperfecta. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2013;10(Suppl 2):397-405. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23858623. Accessed 11 Dec 2014.

Fratzl-Zelman N, Misof BM, Roschger P, Klaushofer K. Classification of osteogenesis imperfecta. Wien Med Wochenschr. 2015;165(13-14):264–70. doi:10.1007/s10354-015-0368-3.

Home - OMIM - NCBI. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/omim. Accessed 18 Feb 2015.

Shapiro JR. Clinical and genetic classification of osteogenesis imperfecta and epidemiology. In: Osteogenesis Imperfecta. Elsevier; 2014:15-22. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-397165-4.00002-2.

Cho T-J, Lee K-E, Lee S-K, et al. A single recurrent mutation in the 5′-UTR of IFITM5 causes osteogenesis imperfecta type V. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;91(2):343–8. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.06.005.

Semler O, Garbes L, Keupp K, et al. A mutation in the 5′-UTR of IFITM5 creates an in-frame start codon and causes autosomal-dominant osteogenesis imperfecta type V with hyperplastic callus. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;91(2):349–57. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.06.011.

Amor IM, Ben F, Rauch K, Gruenwald M, Weis DR, Eyre P. Roughley FH, Glorieux and RM. Severe osteogenesis imperfecta caused by a small in-frame deletion in CRTAP. Am J Med Genet A. 2011;42(11):157–62. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.34269. Severe

van Dijk FS, Zillikens MC, Micha D, et al. PLS3 mutations in X-linked osteoporosis with fractures. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(16):1529–36. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1308223.

Becker J, Semler O, Gilissen C, et al. Exome sequencing identifies truncating mutations in human SERPINF1 in autosomal-recessive osteogenesis imperfecta. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88(3):362–71. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.01.015.

Christiansen HE, Schwarze U, Pyott SM, et al. Homozygosity for a missense mutation in SERPINH1, which encodes the collagen chaperone protein HSP47, results in severe recessive osteogenesis imperfecta. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;86(3):389–98. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.01.034.

Willaert a, Malfait F, Symoens S, et al. Recessive osteogenesis imperfecta caused by LEPRE1 mutations: clinical documentation and identification of the splice form responsible for prolyl 3-hydroxylation. J Med Genet. 2009;46:233–41. doi:10.1136/jmg.2008.062729

Marini JC, Reich A, Smith SM. Osteogenesis imperfecta due to mutations in non-collagenous genes: lessons in the biology of bone formation. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2014;26(4):500–7. doi:10.1097/MOP.0000000000000117.

Alanay Y, Avaygan H, Camacho N, et al. Mutations in the gene encoding the RER protein FKBP65 cause autosomal-recessive osteogenesis imperfecta. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;86(4):551–9. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.02.022.

Bardai G, Moffatt P, Glorieux FH, Rauch F. DNA sequence analysis in 598 individuals with a clinical diagnosis of osteogenesis imperfecta: diagnostic yield and mutation spectrum. Osteoporos Int. 2016;27(12):3607–13. doi:10.1007/s00198-016-3709-1.

van Dijk FS, Cobben JM, Kariminejad A, et al. Osteogenesis imperfecta: a review with clinical examples. Mol Syndromol. 2011;2(1):1–20. doi:000332228.

Dalgleish R. The human collagen mutation database 1998. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26(1):253–5. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9399846. Accessed 5 Apr 2017

Statistics Estonia. The population of Estonia increased last year––statistics Estonia. http://www.stat.ee/news-release-2017-008. Accessed 5 Apr 2017.

Maasalu K, Haviko T, Märtson A. Treatment of children with osteogenesis imperfecta in Estonia. Acta Paediatr. 2007;92(4):452–5. doi:10.1111/j.1651-2227.2003.tb00577.x.

Sinnwell JP, Therneau TM, Schaid DJ. The kinship2 R package for pedigree data. Hum Hered. 2014;78(2):91–3. doi:10.1159/000363105.

Ho Duy B, Zhytnik L, Maasalu K, et al. Mutation analysis of the COL1A1 and COL1A2 genes in Vietnamese patients with osteogenesis imperfecta. Hum Genomics. 2016;10(1):27. doi:10.1186/s40246-016-0083-1.

Home - SNP - NCBI. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/snp. Accessed 11 Apr 2017.

Genomes | A deep catalog of human genetic variation. http://www.internationalgenome.org/. Accessed 11 Apr 2017.

Kumar P, Henikoff S, Ng PC. Predicting the effects of coding non-synonymous variants on protein function using the SIFT algorithm. Nat Protoc. 2009;4(7):1073–81. doi:10.1038/nprot.2009.86.

Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L, et al. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat Methods. 2010;7(4):248–9. doi:10.1038/nmeth0410-248.

Schwarz JM, Rödelsperger C, Schuelke M, Seelow D. MutationTaster evaluates disease-causing potential of sequence alterations. Nat Methods. 2010;7(8):575–6. doi:10.1038/nmeth0810-575.

Dalgleish R. The human type I collagen mutation database. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25(1):181–7. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9016532. Accessed 5 Apr 2017

Chen R, Mias GI, Li-Pook-Than J, et al. Personal omics profiling reveals dynamic molecular and medical phenotypes. Cell. 2012;148(6):1293–307. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.009.

Bodian DL, Chan T-F, Poon A, et al. Mutation and polymorphism spectrum in osteogenesis imperfecta type II: implications for genotype-phenotype relationships. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18(3):463–71. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddn374.

Hartikka H, Kuurila K, Körkkö J, et al. Lack of correlation between the type of COL1A1 or COL1A2 mutation and hearing loss in osteogenesis imperfecta patients. Hum Mutat. 2004;24(2):147–54. doi:10.1002/humu.20071.

Pollitt R, McMahon R, Nunn J, et al. Mutation analysis of COL1A1 and COL1A2 in patients diagnosed with osteogenesis imperfecta type I–IV. Hum Mutat. 2006;27(7):716. doi:10.1002/humu.9430.

Lindahl K, Åström E, Rubin C-J, et al. Genetic epidemiology, prevalence, and genotype–phenotype correlations in the Swedish population with osteogenesis imperfecta. Eur J Hum Genet. 2015;23(8):1042–50. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2015.81.

Lin H-Y, Chuang C-K, Su Y-N, et al. Genotype and phenotype analysis of Taiwanese patients with osteogenesis imperfecta. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2015;10:152. doi:10.1186/s13023-015-0370-2.

Lee K-S, Song H-R, Cho T-J, et al. Mutational spectrum of type I collagen genes in Korean patients with osteogenesis imperfecta. Hum Mutat. 2006;27(December 2005):599. doi:10.1002/humu.9423

Yang Z, Ke ZF, Zeng C, Wang Z, Shi HJ, Wang LT. Mutation characteristics in type I collagen genes in Chinese patients with osteogenesis imperfecta. Genet Mol Res. 2011;10(1):177–85. doi:10.4238/vol10-1gmr984.

Zhang Z-L, Zhang H, Ke Y, et al. The identification of novel mutations in COL1A1, COL1A2, and LEPRE1 genes in Chinese patients with osteogenesis imperfecta. J Bone Miner Metab. 2012;30(1):69–77. doi:10.1007/s00774-011-0284-6.

Marini JC, Forlino A, Cabral WA, et al. Consortium for osteogenesis imperfecta mutations in the helical domain of type I collagen: regions rich in lethal mutations align with collagen binding sites for integrins and proteoglycans. Hum Mutat. 2007;28(3):209–21. doi:10.1002/humu.20429.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the following people and organizations for their help and support with data collection: workers of the Department of Traumatology and Orthopedics and Department of Pathophysiology, University of Tartu, and Ardo Birk and Madis Karu for the development of the online OI database of the Clinic of Traumatology and Orthopedics, TU Hospital.

Funding

This study was supported by the Estonian Science Agency project IUT20-46 (TARBS14046I), the European Regional Development Fund and the Archimedes Foundation to the Centre of Excellence on Translational Medicine, the University of Tartu’s Development Fund, University of Tartu’s Baseline Funding, and the HypOrth Project funded by the European Union’s 7th Framework Programme grant agreement no. 602398.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LZ conceived the study, carried out the genetic studies, performed the data analysis, participated in the design of the study, and drafted the manuscript. EP, SK, and ER carried out the genetic studies, performed the data analysis, and helped to draft the manuscript. KM participated in the design of the study, interacted with the patients, coordinated the blood sample collection, and helped to draft the manuscript and perform analysis. SK and AM participated in the designing of the study, coordinated the data interpretation and statistical analysis, and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The current study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and received approval from the Ethical Review Committee on Human Research of the University of Tartu (permit no. 221/M-34). Informed written consent from the patients or their legal representatives were obtained prior to inclusion to the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhytnik, L., Maasalu, K., Reimann, E. et al. Mutational analysis of COL1A1 and COL1A2 genes among Estonian osteogenesis imperfecta patients. Hum Genomics 11, 19 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40246-017-0115-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40246-017-0115-5