Abstract

Background

The genetics of osteogenesis imperfecta (OI) have not been studied in a Vietnamese population before. We performed mutational analysis of the COL1A1 and COL1A2 genes in 91 unrelated OI patients of Vietnamese origin. We then systematically characterized the mutation profiles of these two genes which are most commonly related to OI.

Methods

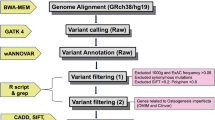

Genomic DNA was extracted from EDTA-preserved blood according to standard high-salt extraction methods. Sequence analysis and pathogenic variant identification was performed with Mutation Surveyor DNA variant analysis software. Prediction of the pathogenicity of mutations was conducted using Alamut Visual software. The presence of variants was checked against Dalgleish’s osteogenesis imperfecta mutation database.

Results

The sample consisted of 91 unrelated osteogenesis imperfecta patients. We identified 54 patients with COL1A1/2 pathogenic variants; 33 with COL1A1 and 21 with COL1A2. Two patients had multiple pathogenic variants. Seventeen novel COL1A1 and 10 novel COL1A2 variants were identified. The majority of identified COL1A1/2 pathogenic variants occurred in a glycine substitution (36/56, 64.3 %), usually serine (23/36, 63.9 %). We found two pathogenic variants of the COL1A1 gene c.2461G > A (p.Gly821Ser) in four unrelated patients and one, c.2005G > A (p.Ala669Thr), in two unrelated patients.

Conclusion

Our data showed a lower number of collagen OI pathogenic variants in Vietnamese patients compared to reported rates for Asian populations. The OI mutational profile of the Vietnamese population is unique and related to the presence of a high number of recessive mutations in non-collagenous OI genes. Further analysis of OI patients negative for collagen mutations, is required.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Osteogenesis imperfecta (OI) is associated with high genetic heterogeneity. To date, mutations in 16 different genes have been found to cause OI phenotypes of varying severity [1]. About 90 % of the mutations are related to alterations in the COL1A1 and COL1A2 genes, located at chromosome 17q21.33 and 7q21.3, respectively [2, 3]. These genes code for the α1/α2 chains of type 1 collagen [1, 4]. It was hypothesized that due to the presence of two α1 and one α2 chains in the procollagen triple helix, the COL1A1 is more susceptible to mutation, as more α1 chains are implemented in the collagen fibrils. COL1A1 gene mutations are more pathogenic and cause OI more often than COL1A2 gene mutations. One third of glycine (Gly) substitutions in the COL1A1 gene are lethal, whereas only 1/5 of Gly pathogenic variants in the COL1A2 gene are fatal [5]. The collagen primary structure differs with an obligatory presence of Gly residues, the smallest amino acid, in every third position of an α chain, composing (Gly-X-Y)n repetitions, where X and Y are random amino acids [6]. The substitution of Gly positioned in the center of the triple helix by a different amino acid would prevent interchain hydrogen bond formation between the NH-group of Gly and the CO-group in the X-position of a neighboring chain. Moreover, substitution of Gly residues with branched nonpolar or charged amino acids changes the helix to bulky and unstructured [5]. In this way, helix strength and stability decrease, which are crucially important for protein function [6–8].

Type 1 collagen is one of the most abundant proteins in the human body. It is a structural component of the bone, skin, tendons, cornea, and blood vessel walls and other connective tissues [4]. OI is generally caused by qualitative or quantitative collagen type I defects [9]. More than 2500 OI mutations have been found in type I collagen genes, which can cause a wide range of OI phenotypes that range in severity from mild to severe [10, 11] (http://www.le.ac.uk/ge/collagen/). Previous studies have shown that COL1A1/2 mutations account for up to 85–90 % of all OI causative mutations, whereas only 10–15 % of OI mutations occur in non-collagenous genes [2, 11, 12]. While in more recent studies, many new genetic causes have been described, the mutations in the COL1A1/2 genes remain a common origin of OI [1, 10]. However, there is a lack of systematic information regarding the mutational characteristics of OI patients. In addition, the genetics of Vietnamese OI patients has not been studied before. Our main aim with the current study was to perform mutational analysis of the COL1A1 and COL1A2 genes among unrelated OI patients of Vietnamese origin. We applied a systematic approach to characterizing the mutation profiles of these two genes.

Materials and methods

The study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and received approval from the ethical review board of Hue University Hospital (approval no. 75/CN-BVYD) and the Ethical Review Committee on Human Research of the University of Tartu (permit no. 221/M-34). Patients were selected from the Vietnamese database of osteogenesis imperfecta patients. The database includes information on 146 OI patients from 120 OI families and also about their healthy family members. A total of 91 unrelated OI patients were included in the study. Informed written consent from the patients or their legal representatives was obtained prior to inclusion to the study. Investigators then contacted patients in order to conduct an interview, perform a clinical examination, and collect blood samples, including blood samples from parents, siblings, and close relatives. Genomic DNA was extracted from EDTA-preserved blood according to standard high-salt extraction methods, stored at −80 °C, and analyzed at the University of Tartu, Estonia.

DNA samples were amplified using a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with 25 specially designed primer pairs covering the 5′ UTR and 3′ UTR regions and 51 exons of the COL1A1 gene; 36 primer pairs covering the 5′ UTR and 3′ UTR regions and 52 exons of the COL1A2 gene. The PCR reaction was performed in a total volume of 20 μl, which included 4 μl of 5× HOT FIREPol® Blend Master Mix Ready to Load with 7.5 mM MgCl2 (Solis BioDyne, Estonia), 1 μl each of forward and reverse primer (5 pmol), and 1 μl of gDNA (50 ng). PCR reaction was performed with a Thermal Cycler (Applied Biosystems, USA) PCR machine. The PCR touchdown program was used as follows for the reaction of amplification:

-

1 = 95.0°; 15:00 min

-

2 = 95.0°; 0:25 min

-

3 = 64.0°; 0:30 min

-

4 = 72.0°; 0:40 min

-

5 = go to 2.4 times

-

6 = 95.0°; 0:25 min

-

7 = 62.0°; 0:30 min

-

8 = 72.0°; 0:40 min

-

9 = go to 6.30 times

-

10 = 72.0°; 5:00 min

-

11 = 6.0°; forever

Amplified PCR products were electrophoresed through a 1.5 % agarose gel, to control the quality of fragments. The PCR products then purified with exonuclease I and shrimp alkaline phosphatase (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Sanger sequencing reactions were performed on the purified PCR fragments using a BigDye® Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems, USA). Reactions were processed on the ABI3730xl instrument.

Sequence reads were analyzed using Applied Biosystems’ Sequence Scanner v1.0 and aligned to the human reference genome Local Reference Genomic sequence LGR_1 and GR_2. Raw sequencing data are available from authors upon request. Sequence analysis and pathogenic variant identification were performed with Mutation Surveyor DNA variant analysis software (Softgenetics, USA). Prediction of mutation’s pathogenicity was performed using Alamut Visual software (Interactive Biosoftware, France). Variants were checked against the osteogenesis imperfecta mutation database (http://www.le.ac.uk/ge/collagen/). The pathogenicity of the pathogenic variants was predicted with SIFT score [13].

Results

We studied 42 female and 49 male OI patients. To characterize the OI patients’ clinical features, all participants underwent clinical and physical examinations, and their medical records were reviewed. Cases were described according to the Sillence classification (types I–IV) [14].

Fifty-four patients were found to have COL1A1/2 mutations, 33 with COL1A1 and 21 with COL1A2; this equated to 36.3 and 23.1 % of patients, respectively, totaling 59.4 % of the studied OI cases exhibiting collagen type I mutations. Thirty-four pathogenic variants in the COL1A1 gene (missense = 23, nonsense = 4, splice site = 7) and 22 pathogenic variants in the COL1A2 gene (missense = 21, splice site = 1) were identified (patients VN01 and VN47 were carriers of double pathogenic variants in both the COL1A1/2 genes) (Fig. 1; Tables 1 and 2). According to Dalgliesh database, 17 COL1A1 and 10 COL1A2 variants have not been reported before (Tables 1 and 2). De novo mutations were observed in 50 % (17/34) of COL1A1 variants and 45.5 % (10/22) of COL1A2 variants. All mutations were highly pathogenic, with a SIFT score of 0.0 and rarely 0.1, and located in regions of high conservation.

Discussion

In our study, we performed mutational analysis of 91 Vietnamese patients clinically diagnosed with OI (types I–IV). Thirty-three patients had 34 pathogenic variants of the COL1A1 gene, and 21 patients had 22 pathogenic variants of the COL1A2 gene, equating to a total of 54/91 (59.4 %) patients with COL1A1/2 pathogenic variants. Previous studies have indicated that nearly 90 % of all OI mutations appear in the COL1A1 and COL1A2 genes [12, 15]. However, reported collagen type I mutational rates vary between different populations from 58 to 96 % [16–18].

We identified the substitution of Gly residuals in 17 out of 23 missense COL1A1 mutations and 19 of 21 missense COL1A2 pathogenic variants. Gly substitutions composed 36/56 (64.3 %) of COL1A1/2 pathogenic variants. It has been hypothesized that the majority of the clinically severe forms of OI are caused by Gly missense mutations [17, 18]. However, there may exist a complex relationship between OI pathogenic variant and OI severity, whereby genetic, epigenetic, and environmental factors altogether affect the phenotype [19, 20].

Our research showed that out of 36 glycine substitutions, serine was the most prevalent (23/36; 63.9 %), followed by valine (4/36; 11.1 %), and cysteine and aspartic acid (3/36 cases each). Previous studies have suggested that glycine substitutions by cysteine often cause a greater severity of OI phenotype, and glycine substitutions by arginine were often fatal [21]. However, there are alternative reports that also suggest serine is the most common substitutional residue of Gly (72 % among Chinese OI patients) [18]. Aspartic acid substituted Gly in 40 % of Taiwanese OI patients [22]. The cause of variation in amino acid substitutions among populations of different geographical regions is still unclear.

In our research, intronic variants were represented by seven splice site mutations; other research has reported intronic variants among 7/56 of Chinese OI patients [18]. These mutations may cause exon skipping, intronic inclusion, and activation of cryptic sites [23]. In addition, analyses identified two nonsense mutations located in exons 52 and 37. Nonsense and splice site mutations are associated with haploinsufficiency, and as a result, quantitative collagen type I defects and a mild–moderate OI phenotype (type I/IV).

Patients VN01, VN34, VN40, and VN49 had the same heterozygous mutation: c.2461G > A (p.Gly821Ser) in exon 37 of the COL1A1 gene. With respect to clinical severity, these patients showed nearly the same manifestations (clinical types I and IV). However, previous studies have described OI patients with different clinical features, despite their being carriers of the c.2461G > A mutation. Current data highlights the complexity of OI genotype–phenotype correlations. It is not yet possible to predict disorder severity based only on mutational analysis data.

Families VN88 and VN89 shared the same heterozygous COL1A1 c.2005G > A (p.Ala669Thr) pathogenic variant in exon 30. Two patients had the same pathogenic variant and level of OI severity (type IV). Similar cases of variant reoccurance have been described before by Zhang et al. and Lee et al. in both COL1A1/2 genes [17, 18]. However, OI pathogenic variants are usually unique and rarely repeated among different families [17].

Genetic analysis revealed the presence of two heterozygous COL1A1 mutations: exon 37 c.2461G > A (p.Gly821Ser) and exon 30 c.2005G > A (p.Ala669Thr) in patient VN01. Both pathogenic variants were shared by other unrelated patients among our study cohort. Patient VN47 had two heterozygous COL1A2 pathogenic variants: exon 46 c.3034G > GA (p.Gly1012Ser) and exon 41 c.2569C > CA (p.Pro857Thr). Takagi et al. reported one case of severe OI (types II–III) due to a double substitution of glycine residues in the COL1A2 gene (p.Gly208Glu and p.Gly235Asp), located on the same allele [24]. Our patients had only one substituted Gly residue in the COL1A1 gene and a mild phenotype (VN01) and moderate phenotype (VN47) based on the clinic examination.

Of the 56 mutations found during our research, 17 COL1A1 and 10 COL1A2 variants (27/56 pathogenic variants; 48.2 %) were not present in Dalgleish’s OI mutation database (Tables 1 and 2) [https://oi.gene.le.ac.uk/home.php?select_db=COL1A1; https://oi.gene.le.ac.uk/home.php?select_db=COL1A2]. The percentage of new variants among our patients was higher than in previous studies [16, 22, 25, 26]. The novelty of the pathogenic variants highlights the originality of the genetic epidemiology of the Vietnamese OI population. Half of Vietnamese OI patients are carriers of rare recessive non-collagenous OI pathogenic variants, which will be further identified with the whole exome sequencing analysis and reported in a future paper.

According to our data, more OI causative pathogenic variants occurred in the COL1A1 gene than the COL1A2 gene. Mutation hotspots were observed in intron 1; exons 8, 14–15, 17–20, 30, 33, 34, 37, and 52 of the COL1A1 gene; and exons 17–49 of the COL1A2 gene (Fig. 2). Products of the COL1A1/2 gene consisted of signal peptide, N-terminal propeptide, collagen alpha I/II chain triple helical domain, and C-terminal propeptide (COLFI). COLFI controls procollagen intracellular assembly and the extracellular assembly of collagen fibrils. Mutation hotspots were situated in the regions that tolerate amino acid substitutions, and pathogenic variant resulted in an altered protein, but the organisms were still able to survive. Gaps in the mutation map connected to regions with crucial functions can however lead to fatal alterations [5, 27].

Sequencing primers for the performed Sanger sequencing of the COL1A1 and COL1A2 genes in patients with clinical signs of osteogenesis imperfecta were designed far from intron-exon splice sites, which allowed the identifying of splice site, missense, frameshift, and nonsense mutations in the exons of the COL1A1/2 genes. The gold standard of sequencing, the Sanger method, has an accuracy of approximately 99.9 % [28]. However, it has limitations in identifying whole genes and exon duplications and deletions. Therefore, the number of COL1A1/2 pathogenic variants in the studied OI patients might have been underestimated.

We must also take into consideration that the percentage of collagen pathogenic variants among osteogenesis imperfecta patients may vary between studies due to their different sample sizes. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that the Vietnamese population has lower rates of collagenous OI pathogenic variants, and a unique OI mutational profile with higher levels of rare non-collagenous pathogenic variants, compared to other populations.

Conclusion

In the current study, we conducted mutational analysis of the COL1A1 and COL1A2 genes among 91 Vietnamese patients with osteogenesis imperfecta. After sequencing of the COL1A1 and COL1A2 genes, we found 56 mutations in 54 patients (59.4 % of patients). Our data showed a lower number of collagen OI pathogenic variants in these Vietnamese patients compared to reported rates for other Asian OI populations. The OI mutational profile of the Vietnamese population is likely unique and is related to the presence of a high number of recessive mutations in non-collagenous OI genes. Further analysis of patients negative for collagen OI mutations is needed in order to reveal unidentified OI genotypes from the sample.

Abbreviations

3′ UTR, 3′ untranslated region; 5′ UTR, 5′ untranslated region; COLFI, fibrillary collagen C-terminal domain; EDTA, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid; gDNA, genomic DNA; OI, osteogenesis imperfecta; PCR, polymerase chain reaction

References

Van Dijk FS, Sillence DO. Osteogenesis imperfecta: clinical diagnosis, nomenclature and severity assessment. Am J Med Genet A. 2014;164A:1470–81.

van Dijk FS, Byers PH, Dalgleish R, et al. EMQN best practice guidelines for the laboratory diagnosis of osteogenesis imperfecta. Eur J Hum Genet. 2012;20:11–19.

Rauch F, Glorieux F. Osteogenesis imperfecta. Lancet. 2004;363(9418):1377–85.

Pokidysheva E, Mizuno K, Bächinger HP. The collagen folding machinery: Biosynthesis and post-translational modifications of collagens. In: Jay R. Shapiro, Peter H. Byers, Francis H. Glorieux, Paul D. Sponseller, editors. Osteogenesis imperfecta a translational approach to brittle bone disease. London: Elsevier; 2014. p.57–70.

Marini JC, Forlino A, Cabral WA, Barnes AM, San Antonio JD, Milgrom S, et al. Consortium for osteogenesis imperfecta mutations in the helical domain of type I collagen: regions rich in lethal mutations align with collagen binding sites for integrins and proteoglycans. Hum Mutat. 2007;28:209–21.

Gelse K. Collagens—structure, function, and biosynthesis. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2003;55:1531–46.

Kadler KE, Holmes DF, Trotter JA, Chapman JA. Collagen fibril formation. J Biochem. 1996;316:1–11.

Makareeva E, Leikin S. Collagen structure, folding and function. In: Jay R. Shapiro, Peter H. Byers, Francis H. Glorieux, Paul D. Sponseller, editors. Osteogenesis Imperfecta. A translational approach to brittle bone disease. London: Elsevier; 2014. p.71–84.

Marini J, Smith SM. Osteogenesis Imperfecta MDText.com, Inc. 2015.

Zukowsky K, Editor CS. Osteogenesis Imperfecta types I–XI. 2014;1–7.

Basel D, Steiner RD. Osteogenesis imperfecta: recent findings shed new light on this once well-understood condition. Genet Med. 2009;11:375–85.

Pollitt R, McMahon R, Nunn J, Bamford R, Afifi A, Bishop N, et al. Mutation analysis of COL1A1 and COL1A2 in patients diagnosed with osteogenesis imperfecta type I-IV. Hum Mutat. 2006;27:716.

Kumar P, Henikoff S, Ng PC. Predicting the effects of coding non-synonymous variants on protein function using the SIFT algorithm. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:1073–81.

Sillence DO, Senn A, Danks DM. Genetic heterogeneity in osteogenesis imperfecta. J Med Genet. 1979;16:101–16.

Shaker JL, Albert C, Fritz J, Harris G. Recent developments in osteogenesis imperfecta F1000Res. 2015;4:681. doi:10.12688/f1000research.6398.1.

Stephen J, Shukla A, Dalal A, Girisha KM, Shah H, Gupta N, et al. Mutation spectrum of COL1A1 and COL1A2 genes in Indian patients with osteogenesis imperfecta. Am J Med Genet Part A. 2014;164:1482–9.

Lee K-S, Song H-R, Cho T-J, Kim HJ, Lee T-M, Jin H-S, et al. Mutational spectrum of type I collagen genes in Korean patients with osteogenesis imperfecta. Hum Mutat. 2006;27:599.

Zhang Z-L, Zhang H, Ke Y, Yue H, Xiao W-J, Yu J-B, et al. The identification of novel mutations in COL1A1, COL1A2, and LEPRE1 genes in Chinese patients with osteogenesis imperfecta. J Bone Miner Metab. 2012;30:69–77.

Roughley PJ, Rauch F, Glorieux FH. Osteogenesis imperfecta—clinical and molecular diversity. Eur Cell Mater. 2003;5:41–7. discussion 47.

Kataoka K, Ogura E, Hasegawa K, Inoue M, Seino Y, et al. Mutations in type I collagen genes in Japanese osteogenesis imperfecta patients. Pediatr Int. 2007;49:564–9.

Cole WG, Chow CW, Rogers JG, Bateman JF. The clinical features of three babies with osteogenesis imperfecta resulting from the substitution of glycine by arginine in the pro alpha 1(I) chain of type I procollagen. J Med Genet. 1990;27:228–35.

Lin H-Y, Chuang C-K, Su Y-N, Chen M-R, Chiu H-C, Niu D-M, et al. Genotype and phenotype analysis of Taiwanese patients with osteogenesis imperfecta. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2015;10:152.

Kuivaniemi H, Tromp G, Prockop DJ. Mutations in fibrillar collagens (types I, II, III, and XI), fibril-associated collagen (type IX), and network-forming collagen (type X) cause a spectrum of diseases of bone, cartilage, and blood vessels. Hum Mutat. 1997;9:300–15.

Takagi M, Kouwaki M, Kawase K, Shinohara H, Hasegawa Y, Yamada T, et al. Severe osteogenesis imperfecta caused by double glycine substitutions near the amino-terminal triple helical region in COL1A2. Am J Med Genet Part A. 2015;167:2851–4.

Yang Z, Ke ZF, Zeng C, Wang Z, Shi HJ, Wang LT. Mutation characteristics in type I collagen genes in Chinese patients with osteogenesis imperfecta. Genet Mol Res. 2011;10:177–85.

Ward LM, Lalic L, Roughley PJ, Glorieux FH. Thirty-three novel COL1A1 and COL1A2 mutations in patients with osteogenesis imperfecta types I-IV. Hum Mutat. 2001;17:434.

Sweeney SM, Orgel JP, Fertala A, McAuliffe JD, Turner KR, Di Lullo GA, et al. Candidate cell and matrix interaction domains on the collagen fibril, the predominant protein of vertebrates. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:21187–97.

Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson AR. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1977;74:5463–7.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the following people and organizations for their help and support with data collection: The Vietnamese National Hospital of Pediatrics; Hanoi OI Center; OI Booming Diamond Center in Ho Chi Minh City; Hue University Hospital; and The University of Tartu. This research would not have been possible without the support, teaching, and cooperation of the Department of Traumatology and Orthopaedics and Department of Pathophysiology of University of Tartu.

Funding

This work was supported by institutional research funding IUT20-46 of the Estonian Ministry of Education and Research and the European Union’s European Regional Development Fund Programme “Supporting international cooperation in R&D” projects “EVMED” and “DIOXMED.” The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under grant agreement no. 602398.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article, including raw sequencing and clinical data, is available from authors upon request.

Authors’ contributions

HDB conceived the study, participated in its design, interacted with the patients, coordinated the blood sample collection, and drafted the manuscript. LZ, IK, EP, SK, ER carried out the genetic studies, performed the data analysis, and helped to draft the manuscript. KM participated in its design, interacted with the patients, coordinated the blood sample collection, and helped to draft the manuscript. SK and AM participated in the design of the study, coordinated the data interpretation and statistical analysis and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and received approval from the ethical review board of Hue University Hospital (approval no. 75/CN-BVYD) and the Ethical Review Committee on Human Research of the University of Tartu (permit no. 221/M-34). Informed written consent from the patients or their legal representatives was obtained prior to inclusion to the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Ho Duy, B., Zhytnik, L., Maasalu, K. et al. Mutation analysis of the COL1A1 and COL1A2 genes in Vietnamese patients with osteogenesis imperfecta. Hum Genomics 10, 27 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40246-016-0083-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40246-016-0083-1