Abstract

Background

Inappropriate over-the-counter supply of antibiotics in pharmacies for common infections is recognised as a source of antibiotic misuse that can worsen the global burden of antibiotic resistance.

Objectives

To assess responses of community pharmacy staff to pseudo-patients presenting with symptoms of common infections and factors associated with such behaviour.

Methods

A cross-sectional pseudo-patient study was conducted from Jan-Sept 2017 among 242 community pharmacies in Sri Lanka. Each pharmacy was visited by one trained pseudo-patient who pretended to have a relative with clinical symptoms of one of four randomly selected clinical scenarios of common infections (three viral infections: acute sore throat, common cold, acute diarrhoea) and a bacterial uncomplicated urinary tract infection. Pseudo-patients requested an unspecified medicine for their condition. Interactions between the attending pharmacy staff and the pseudo-patients were audio recorded (with prior permission). Interaction data were also entered into a data collection form immediately after each visit.

Results

In 41% (99/242) of the interactions, an antibiotic was supplied illegally without a prescription. Of these, 66% (n = 65) were inappropriately given for the viral infections. Antibiotics were provided for 55% of the urinary tract infections, 50% of the acute diarrhoea, 42% of the sore throat and 15% of the common cold cases. Patient history was obtained in less than a quarter of the interactions. In 18% (44/242) of the interactions staff recommended the pseudo-patient to visit a physician, however, in 25% (11/44) of these interactions an antibiotic was still dispensed. Pharmacy staff advised the pseudo-patient on how to take (in 60% of the interactions where an antibiotic was supplied), when to take (47%) and when to stop (22%) the antibiotics supplied. Availability of a pharmacist reduced the likelihood of unlawful antibiotic supply (OR = 0.53, 95% CI: 0.31–0.89; P = 0.016) but not appropriate practice.

Conclusions

Illegal and inappropriate dispensing of antibiotics was evident in the participating community pharmacies. This may be a public health threat to Sri Lanka and beyond. Strategies to improve the appropriate dispensing practice of antibiotics among community pharmacies should be considered seriously.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Medicines use is appropriate (rational and correct) when patients receive medicines appropriate to their clinical needs, in doses that meet their individual requirements, for an adequate period of time, and at affordable prices [1]. If any one of these conditions is not met, then it is referred to as inappropriate (irrational or incorrect) use of the medicines. It has been estimated that worldwide more than half of medicines are prescribed, dispensed or sold inappropriately [2, 3].

Inappropriate use of antibiotics is a global problem, particularly in the Asian region [4, 5]. It is common to see antibiotics provided inappropriately for self-limiting viral infections such as upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs) [5,6,7,8] and acute diarrhoea [6, 9], as well as bacterial infections including urinary tract infections (UTIs) [6, 10]. Inappropriate prescribing of antibiotics is observed in many developing countries [11] and though most of the URTIs are viral infections [12], there appears to be a high prevalence of antibiotic prescriptions provided for viral URTIs in developing and transitional countries, ranging from about 40 to 75% and for acute diarrhoea from about 20 to 55% [11]. A recent country-specific analysis reported a high rate of antibiotic use for viral URTIs in public primary care facilities in South East Asian countries, including Bangladesh (59% of viral URTIs were being treated with antibiotics); Bhutan (34%); Korea (65%); Rajasthan, India (94%); Karnataka, India (70%); Indonesia (72%); Maldives (43%); Myanmar (87%); Sri Lanka (70%); Thailand (43%) and East Timor (55%) [5].

Self-medication with antibiotics is also a major contributory factor to inappropriate use of antibiotics in the community [13]. The emergence and spread of antibiotic resistance (ABR), especially the appearance of multidrug-resistant bacterial strains which are highly resistant to many antibiotic classes, has raised a major global public health concern [14] and has been linked to the inappropriate use of antibiotics [15,16,17]. ABR is also associated with increased morbidity, mortality and treatment costs [18, 19] and the greatest burden occurs in low and middle-income countries (LMICs) [19]. If no actions are taken, it has been estimated that antimicrobial resistance will lead to 10 million deaths by 2050, and a loss of US$100 trillion of the world economic output [20,21,22].

A systematic review of nine surveys conducted in the Asian region, found that self-medication with non-prescription antimicrobials among the general public was 58% (7761 out of 13,366 of weighted cases) [16]. Studies have found that the main source of antibiotics used for self-medication is community pharmacies (CPs) [6, 16, 23, 24]. In China, Ye et al. reported that about 80% of the public purchased antibiotics without a prescription from CPs for self-medication [23]. In LMICs, the preferred method for purchasing medicines is through private pharmacies and often without a prescription. In Bangladesh, the public with a low income identified CPs as an important source of healthcare for all common health problems [25]. As in most LMICs, CPs or drug stores are usually a patient’s first point of contact with the healthcare system for advice on common ailments and other health problems [26]. The main reasons for this include, but are not limited to, patients’ inability to pay for both physician consultation fee and the prescribed medicine(s), limited time to visit a physician, and pharmacy specific factors, such as ease of access, long opening hours, the ability to purchase medicines in small quantities, credit facilities and personal familiarity and relationship with the pharmacist [27,28,29]. The people to physician ratio in most of the LMICs is lower than the 2010 WHO recommended ratio of 400:1 [30] and could also be one of the factors for people visiting pharmacies as a first point of contact with a healthcare professional.

Therefore, community pharmacists, being the first healthcare professional most people in LMICs approach for medical advice, such as common viral infections, are in the best position to help people with appropriate use of medicines. Pharmacists have the antibiotics knowledge necessary to ensure rational use of antibiotics [31] and can contribute to reducing ABR in the community. They can also contribute to the appropriate and safe use of antibiotics by providing advice to patients on antibiotics supply for prescription. In addition, pharmacists can play an important role in managing common infections by providing appropriate over-the-counter (OTC) medicines and non-pharmacological treatments, and referring patients to a medical practitioner, when necessary.

However in many LMICs, community pharmacists are selling antibiotics inappropriately for self-limiting viral URTIs [32,33,34,35], acute diarrhoea [32, 35, 36] and uncomplicated UTIs [32, 34]. Concerns have been raised about such inappropriate antibiotic dispensing practice due to profit aspirations, low quality of practice, insufficient drug sellers’ knowledge and training [28, 35, 37, 38]. Whilst anecdotally, there is evidence for supply of antibiotics without a prescription in Sri Lanka, there is very little empirical research on the provision of antibiotics in Sri Lankan community pharmacies. Therefore, this study aimed to determine community pharmacy staff’s (pharmacist or any other staff who attended to the pseudo-patient) responses when a pseudo-patient presented with symptoms of common infections and possible factors associated with such behaviour.

Methods

Study design

This pseudo-patient study was part of a larger study conducted among Sri Lankan CPs from January to September 2017. There were two arms to this study; one of which involved pseudo-patients’ direct antibiotic product requests (DPR) from 242 CPs throughout Sri Lanka [39]. The current findings were from the second arm, which involved pseudo-patient visits to the same 242 pharmacies but presenting with the clinical symptoms of one of four scenarios of common infections (symptoms-based requests- SBRs) including, acute sore throat (adult female), common cold (four year-old child), acute diarrhoea (adult male) and UTI (adult female). The DPR and SBR visits were conducted randomly within a time interval of approximately two to six weeks apart.

The pseudo-patient approach can be considered as a robust methodological tool for pharmacy practice research, especially as the knowledge of being observed can lead to behavioural change [40, 41]. Despite its own methodological disadvantages, in general, the pseudo-patient method increases the validity of the study design and accuracy of the findings compared to other self-reported qualitative or quantitative surveys mainly because of the absence of social-desirability bias [42, 43].

Sample size calculation and sampling

The sample size for this study was derived from a previous phase: a self-reported cross-sectional country survey conducted among CP staff in Sri Lanka. The survey sample size (n = 369) was calculated based on the results of a previous pilot study (Zawahir S, Amarasinghe M, Hassali MA, Lekamwasam S: Knowledge, attitudes and practices related to antibiotic use among community and hospital pharmacists in district galle, Sri Lanka, Preparation) and the sample size calculation has been detailed in a previous publication [39]. A total of 267 (72%) pharmacies agreed to participate in the self-reported survey and all agreed to be approached to obtain consent for pseudo-patient visits and audio recordings of the visits. However, 243 pharmacies agreed to participate in the pseudo-patient visits and eventually 242 visits were made as one pharmacy went out of the business during the study. A total of 204 agreed to an audio recording of the interaction during the visit.

Clinical scenarios and data collection

The scenarios were developed based on previously published literature [32, 44]. The scenarios and expected visit outcomes are detailed in Table 1. The pseudo-patients with the symptoms of viral infections were expected to be appropriately advised and provided with suitable OTC medicines (if necessary) and the pseudo-patients with uncomplicated UTI symptoms were expected to be referred to a physician.

Thirty-two pseudo-patients were involved in the visits. They were either recent pharmacy graduates or pharmacy students from two public universities. The research assistants who were involved in obtaining informed consent, did not participate in the pseudo-patient visits. Each of the participating pharmacies was visited by a pseudo-patient and a research assistant. While the pseudo-patient interacted with the pharmacy staff, the accompanying research assistant observed and covertly audio recorded the interaction during the visits. Each pseudo-patient requested an unspecified medicine for the treatment of the symptoms of one of four randomly selected clinical scenarios of common infections (acute sore throat, common cold, acute diarrhoea (possible viral infections), and a bacterial uncomplicated UTI). Three levels of requests were made by the pseudo-patient to obtain an antibiotic. The first level of request consisted of requesting an unspecified medicine to alleviate the reported symptoms of the common infection. If an antibiotic was not given, the pseudo-patient used the second level of the request; “Can’t you give me something stronger?” If the pharmacy staff did not provide an antibiotic, the pseudo-patient openly stated, “I would like an antibiotic,” which was considered as the third level of request. If the pharmacy staff asked any questions related to reported symptoms, pseudo-patients were trained to answer according to the pre-determined scenarios.

In addition, advice provided by pharmacy staff and the availability of a pharmacist during the visit were noted. The availability of a pharmacist was confirmed as follows, a research assistant observed the pharmacy licence displayed in the pharmacy with a photograph of the pharmacist. If the photo displayed did not match the attending pharmacy staff or there was no photo displayed, then the pseudo-patient asked “Can I talk to your pharmacist, please?” The availability of the pharmacist was then based on the response to this question. In Sri Lanka, the licence issued by the National Medicine Regulatory Authority to run a community pharmacy should be displayed in the pharmacy with the photo of a pharmacist who owns the pharmacy or is employed [45].

Although as part of the visit the pseudo-patient did not ask why an antibiotic was not provided, any reason stated spontaneously by the pharmacy staff was captured from the audio-recording and reported accordingly.

Immediately after each visit, the pseudo-patient and research assistant completed the data collection sheet (Table 2) together while listening to the audio recording. The questions in the data collection sheet were based on WWHAM (Who for, What symptoms, How long, Any medicine tried, other Medication taken) [46] and What-Stop-Go [47] protocols.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics such as frequencies (%) were used to describe the data. Pearson’s chi-square test and binary logistic regression analysis were performed using independent predictors (availability of pharmacist, gender, geographical area of the pharmacy, type of scenario presented and type of pharmacy) to evaluate the possible factors associated with antibiotic supply without a prescription for reported common infections. The P value of < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. SPSS version 24 was used for all the analyses.

Results

A total of 242 pharmacies were visited by the pseudo-patients. The types of pharmacies which agreed to the pseudo-patient visits included, private chain pharmacies (45%; 109/242), private single pharmacies (43.8%; 106/242), semi-government pharmacies (7%; 17/242) and pharmacies in private hospitals (4.1%; 10/242). The clinical scenario of uncomplicated UTI of adult female was presented to 62 CPs and the other three scenarios - acute sore throat (adult), common cold (four-year-old child) and acute diarrhoea (adult), were presented equally among 180 pharmacies.

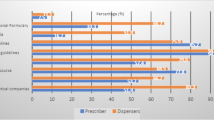

Overall, in 41% (99/242) of instances, antibiotics were sold illegally without a prescription in response to the pseudo-patients reported clinical symptoms (Table 3). The adults’ pseudo-patient scenarios of acute sore throat, acute diarrhoea, and uncomplicated UTI accounted for the highest proportions of illegal antibiotic sales (49%; 90/182), whereas pharmacy staff were more reluctant to sell antibiotics without a prescription when pseudo-patients presented with the symptoms of the common cold for a child (15%; 9/60). The adult common infection scenarios were significantly more likely to receive antibiotics compared to the paediatric one, χ2 (1, N = 242) = 22.15, P < 0.001). In two-thirds of the instances antibiotics were sold inappropriately for underlying viral infections (65/99) including acute sore throat, common cold and acute diarrhoea. In the majority of instances an antibiotic was sold upon the 1st or 2nd level of request (73%; 72/99) without the pseudo-patient requesting an antibiotic by name, and the rest were supplied on the 3rd level of request (Fig. 1). About half of the visited pharmacies were observed to have a pharmacist on duty. In about two-thirds of the instances (61%; 60/99) antibiotics were sold by a pharmacy staff member other than a qualified pharmacist. Though availability of a pharmacist significantly reduced the likelihood of antibiotics supply without a prescription (OR = 0.53, 95% CI: 0.31 to 0.89; P = 0.016), that was not impacted on antibiotic supply between viral and bacterial infections (OR = 1.02, 95% CI: 0.41 to 2.53; P = 0.972).

Overall, only a few pharmacy staff asked the pseudo-patients about concurrent medical conditions (10%; 25/242), any action that has already been taken (8%; 20/242) and concurrent medicines used (1.7%; 4/242). In 18% (44/242) of the instances, pseudo-patients were recommended to see a physician. However, in about a quarter of them (25%; 11/44) an antibiotic was still provided. Only a quarter of the pseudo-patients with UTI (24%; 15/62) were advised to see a physician (Table 4).

In about one-third of the pharmacies (36%; 36/99) where an antibiotic was sold, the pseudo-patients were further questioned about their symptoms or concurrent medical conditions. The questions related to action that has already been taken (12%; 12/99), drug allergies (10%; 10/99), and concurrent medicines used (2%; 2/99). About half of the pseudo-patients were advised on how and how often to take the provided antibiotic, and about a quarter of them were advised on when to stop taking the antibiotic. Availability of a pharmacist in the pharmacy had no impact on patient counselling. In none of the pharmacies did staff inquire about the pregnancy status of the pseudo-patients when selling an antibiotic for a childbearing-aged female pseudo-patient presenting with symptoms of UTI (Table 4). None of the pseudo-patients with diarrhoea were questioned about important symptoms, such as, the presence of blood in stool, fever, prolonged episodes of watery stools, or significant complications of diarrhoea such as dehydration and vomiting. The median interaction time between the pseudo-patients who received an antibiotic and pharmacy staff was 2 min (IQR = 1–3 min).

The most common antibiotic sold to pseudo-patients with sore throat was erythromycin (65%; 17/26), amoxicillin for common cold (89%; 8/9), metronidazole for acute diarrhoea (79%; 23/29) and ciprofloxacin for female UTI cases (77%; 26/34) (Table 3).

In 143 pharmacies, the staff did not provide an antibiotic to the pseudo-patient. The primary reason for not supplying an antibiotic was the absence of a prescription from a physician (100/143; 70%). None of the pharmacy staff discussed the reported symptoms with the pseudo-patient. They did not discuss issues such as severity of the current health condition, possible aetiology of the infection, risk of emergence of ABR if an antibiotic is inappropriately supplied for a viral infection and risk of supplying an antibiotic for a possible bacterial infection (UTI) without being diagnosed by a physician. Instead, they simply denied giving an antibiotic with or without stating a reason. The median interaction time between the pseudo-patient who did not receive an antibiotic and pharmacy staff was also 2 min (IQR = 1–3 min).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is one of the first two pseudo-patient studies conducted in Sri Lanka, including all different types of community pharmacies throughout the country, to evaluate pharmacy staff’s behaviour when presented with symptoms of common infections.

Despite Sri Lankan laws explicitly prohibiting the supply of any antibiotic without a prescription, regardless of the patient’s medical condition or symptoms, this study found that antibiotics were not only commonly provided without a prescription (illegal) for common infections, but also inappropriately for viral infections. The antibiotics were supplied without even being specifically requested by the pseudo-patients. In addition, pharmacy staff failed to adequately inquire about the presenting symptoms, give correct advice or offer alternative OTC products. However, the overall supply was lower when the presenting common infection was that of a child’s, and when a pharmacist was present.

The current results showed that unlawful antibiotic supply was high (41%) and this finding was supported by DPR pseudo-patient visit findings from the same pharmacies, where antibiotics were provided without a prescription to pseudo-patients in 61% of the interactions [39]. The major reason for the prevailing situation with regard to unlawful antibiotic supply among community pharmacies in Sri Lanka may be poor regulation of antibiotics supply in the country and this has been discussed in the DPR arm of the study [39]. A similar poor regulation of medication-dispensing policies has also accounted for variable rates of non-prescription antibiotic sales in other parts of the world [16, 27, 32, 40, 48].

This study also revealed inappropriate supply of antibiotics in response to reported symptoms of common infections of viral aetiology. As the pseudo-patient clinical scenarios were representing possible viral infections (acute sore throat, common cold and acute diarrhoea) and a probable bacterial infection (uncomplicated UTI), the expected behaviour of the staff for the reported scenarios was to effectively obtain relevant medical and lifestyle-related history, advise the pseudo-patient appropriately, provide an OTC medicine or non-pharmacological treatment (as necessary, for viral infections) or refer them to a physician (in the case of UTI). Despite this fact about two thirds of staff who gave out an antibiotic, had supplied them inappropriately for viral infections. The potential reasons for such behaviour of community pharmacy staff have been discussed in a recent self-reported national survey conducted among community pharmacy staff in Sri Lanka which mainly highlighted staff’s inadequate clinical experience and knowledge about antibiotics (Zawahir S, Lekamwasam S, Aslani P: A cross-sectional national survey of community pharmacy staff: knowledge and antibiotic provision, submitted). Similar behaviour has also been observed in many other LMICs [16, 32, 35, 49]. A pseudo-patient study conducted in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia found that irrespective of the aetiology of the infections, antibiotics were freely dispensed without a prescription for all the presented clinical symptoms of sore throat, acute sinusitis, otitis media, acute bronchitis, diarrhoea and UTI [32]. Ayele at el., found that community pharmacy staff in Northwest Ethiopia dispensed antibiotics inappropriately for self-limiting acute diarrhoea and URTIs [35]. Illegal and inappropriate supply of antibiotics in pharmacies will not only promote ABR but also be associated with significant adverse events including drug side effects, high medical costs, and complications of infections leading to longer hospital stays and possible emergence of multi drug resistance.

When comparing the findings of the DPR arm of the study [39] to the current SBR study findings, it can be seen that a large proportion of the pharmacies supplied antibiotics illegally, on both occasions when visited by the pseudo-patient. This demonstrates that, potentially, the same reasons explain the provision of antibiotics without a prescription, whether the pseudo-patient requests an antibiotic by name [39] or presents with symptoms of a common infection which the pharmacy staff believe can be treated by an antibiotic. Therefore, there is substantial room for practice improvement, both in increasing clinical knowledge as well as enforcing the legal requirements surrounding antibiotics supply. However, the current study found that the proportion of community pharmacies providing an antibiotic without a prescription was 20% less when there was a SBR compared to a DPR. This difference may be due to several reasons. The observed higher prevalence of antibiotic supply during DPR may be due to the staff’s false perception that when the patient is requesting an antibiotic by a specific product name, the patient has knowledge about it or has had previous experience in using it. They may therefore feel more confident in providing an antibiotic. In the case of SBR, the pseudo-patient was required to describe the symptoms to the pharmacy staff, which may have initiated more discussion and an increased effort from the staff to appropriately diagnose and provide treatment options other than an antibiotic. Furthermore, the staff may have felt that the pseudo-patient had not tried any products in the past, and so they may have been less confident in providing an antibiotic.

The observed low proportion of antibiotic supply (15%) for the reported paediatric scenario is a positive sign. This could be due to either pharmacy staff’s concern about vulnerable paediatric patients or their lack of clinical competency in dealing with such patients, or perhaps both. As none of the staff determined the cause of the infection and failed to educate the pseudo-patient appropriately whether an antibiotic was needed or not, also supports the argument above about limited clinical training and therefore knowledge of staff.

Further, only about half of the pseudo-patients who obtained antibiotics, received any form of counselling or advice. Counselling patients on “when to stop taking antibiotics” does not appear to be part of the current process of providing antibiotics in Sri Lankan pharmacies. A similar inadequate patient history taking and lack of patient counselling was also observed in the DPR arm of the pseudo-patient study [39]. This is not only a problem in Sri Lanka. Other studies from LMICs have also highlighted similar issues [38, 50]. Pharmacy staff’s beliefs about the usefulness of counselling, time constraints, absence of any patient counselling guidelines in Sri Lanka and/or lack of privacy in community pharmacies and limited clinical knowledge, may have contributed to the poor counselling observed. This provides an important opportunity for continued professional development of Sri Lanka pharmacy staff.

Although it was revealed that the presence of a pharmacist in the pharmacy may have been associated with a lower likelihood of antibiotic supply without a prescription, the presence of the pharmacists did not impact the counselling received by the pseudo-patient nor result in an appropriate response to the reported symptoms of common infections. Therefore, this supports the argument above about limited clinical training and the knowledge of staff. It is also evident from the literature that un-qualified pharmacy staff or pharmacists with poor clinical knowledge may be contributing to inappropriate antibiotic supply [39, 51].

The inappropriate provision of antibiotics and inadequate counselling provided to pseudo-patients observed in this study challenges the goal of appropriate use of antibiotics in communities, and can contribute to global antibiotic misuse [52]. In turn, this can have a serious public health threat through contributing to antibiotic resistance at individual and population levels [53]. Therefore, the prevailing situation related to illegal and inappropriate antibiotic supply in Sri Lanka is not only challenging to the public health of the country, but has global consequences [54].

Limitations

Although repeated training and rehearsals were made to ensure consistency between pseudo-patients and to increase the internal validity of the data collected, it is still possible that some interpersonal differences among pseudo-patients may have impacted the behaviour of the pharmacy staff. This approach may also have limited external validity, since in normal circumstances the pharmacist would probably have much more information about the client. A real patient has the tendency to communicate freely about his/her pathology, therefore, the outcomes measured by this method may vary from real situations [55]. Furthermore, self-selection of the study participants may have impacted the study findings.

Conclusions

It is evident from this study that antibiotics are given out from pharmacies illegally without a prescription and clinically inappropriately. Presence of a pharmacist in the pharmacy may have reduced the illegal supply but it did not appear to impact appropriate practice.

Immediate action is sought from all stakeholders including healthcare professionals, local policy makers as well as global agencies such as WHO, and the public, to curb this public health issue. In addition to strict implementation of policies, awareness and educational interventions must be implemented to improve appropriate antibiotic dispensing practice among pharmacists and their staff.

Abbreviations

- ABR:

-

Antibiotic resistance

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CP:

-

Community pharmacy

- DPR:

-

Direct product request

- LMIC:

-

Low and middle-income countries

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- OTC:

-

Over the counter

- SBR:

-

Symptoms based request

- URTIs:

-

Upper respiratory tract infections

- UTI(s):

-

Urinary tract infection(s)

- WWHAM:

-

Who for, What symptoms, How long, Any medicine tried, other Medication taken

References

WHO. How to develop and implement a national drug policy. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/42423/1/924154547X.pdf. Accessed 5 Aug 2018

WHO. Promoting rational use of medicine: Core components. Who policy perspectives on medicines. World Health Organization. 2002. Available from: http://archives.who.int/tbs/rational/h3011e.pdf. Accessed 9 Jul 2018.

WHO. Medicine use in developing and transitional countries. World Health Organization. 2009. Available from: http://www.who.int/medicines/publications/who_emp_2009.3/en/. Accessed 7 Jul 2018.

Holloway KA. Promoting the rational use of antibiotics. Regional health forum: Who south east asian region. World Health Organization. 2011. Available from: http://www.searo.who.int/publications/journals/regional_health_forum/media/2011/V15n1/rhfv15n1p122.pdf. Accessed 5 Jul 2018.

Holloway KA, Kotwani A, Batmanabane G, Puri M, Tisocki K. Antibiotic use in south east asia and policies to promote appropriate use: reports from country situational analyses. BMJ. 2017;358:9–13.

Alhomoud F, Aljamea Z, Almahasnah R, Alkhalifah K, Basalelah L, Alhomoud FK. Self-medication and self-prescription with antibiotics in the middle east-do they really happen? A systematic review of the prevalence, possible reasons, and outcomes. Int J Infect Dis. 2017;57:3–12.

Kenealy T, Arroll B. Antibiotics for the common cold and acute purulent rhinitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;6(6):CD000247.

Arroll B. Antibiotics for upper respiratory tract infections: an overview of Cochrane reviews. Respir Med. 2005;99(3):255–61.

Karras DJ, Ong S, Moran GJ, Nakase J, Kuehnert MJ, Jarvis WR, et al. Antibiotic use for emergency department patients with acute diarrhea: prescribing practices, patient expectations, and patient satisfaction. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;42(6):835–42.

Gupta K, Hooton TM, Naber KG, Wullt B, Colgan R, Miller LG, et al. International clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis in women: a 2010 update by the infectious diseases society of america and the european society for microbiology and infectious diseases. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(5):e103–e20.

Holloway K, Dijk Lv. The world medicines situation 2011. Rational use of medicines. World Health Organization 2011. Available from: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/en/d/Js18064en/. Accessed 10 Aug 2018.

Sumpradit N, Wongkongkathep S, Poonpolsup S, Janejai N, Paveenkittiporn W, Boonyarit P, et al. New chapter in tackling antimicrobial resistance in Thailand. BMJ. 2017;358(Suppl 1):20–4.

Grigoryan L, Burgerhof JGM, Degener JE, Deschepper R, Lundborg CS, Monnet DL, et al. Determinants of self-medication with antibiotics in europe: the impact of beliefs, country wealth and health care system. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;61(5):1172–9.

Kumarasamy KK, Toleman MA, Walsh TR, Bagaria J, Butt F, Balakrishnan R, et al. Emergence of a new antibiotic resistance mechanism in India, Pakistan, and the UK: a molecular, biological, and epidemiological study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10(9):597–602.

Goossens H, Ferech M, Vander Stichele R, Elseviers M, Grp EP, Group EP. Outpatient antibiotic use in Europe and association with resistance: a cross-national database study. Lancet. 2005;365(9459):579–87.

Morgan DJ, Okeke IN, Laxminarayan R, Perencevich EN, Weisenberg S. Non-prescription antimicrobial use worldwide: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11(9):692–701.

Costelloe C, Metcalfe C, Lovering A, Mant D, Hay AD. Effect of antibiotic prescribing in primary care on antimicrobial resistance in individual patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2010;340:1–11.

Laxminarayan R, Duse A, Wattal C, Zaidi AK, Wertheim HF, Sumpradit N, et al. Antibiotic resistance-the need for global solutions. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13(12):1057–98.

Founou RC, Founou LL, Essack SY. Clinical and economic impact of antibiotic resistance in developing countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12(12):e0189621.

WHO. Global action plan on antimicrobial resistance. World Health Organization. 2015. Available from: http://www.who.int/antimicrobial-resistance/global-action-plan/en/. Accessed 2 June 2018.

WHO. Global priority list of antibiotic-resistance bacteria to guide research, discovery, and development of new antibiotics. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. Available from: http://www.who.int/medicines/publications/global-priority-list-antibiotic-resistant-bacteria/en/. Accessed 4 Jun 2018

Jim O’Neill. Tackling drug-resistant infections globally. 2016. Available from: https://amr-review.org/sites/default/files/160518_Final%20paper_with%20cover.pdf. Accessed 1 June 2018.

Ye D, Chang J, Yang C, Yan K, Ji W, Aziz MM, et al. How does the general public view antibiotic use in China? Result from a cross-sectional survey. Int J Clin Pharm. 2017;39(4):927–34.

Pavydė E, Veikutis V, Mačiulienė A, Mačiulis V, Petrikonis K, Stankevičius E. Public knowledge, beliefs and behavior on antibiotic use and self-medication in Lithuania. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12(6):7002–16.

Khan MMH, Grbner O, Krämer A. Frequently used healthcare services in urban slums of Dhaka and adjacent rural areas and their determinants. J Publ Health (United Kingdom). 2012;34(2):261–71.

Smith F. The quality of private pharmacy services in low and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Pharm World Sci. 2009;31(3):351–61.

Barker AK, Brown K, Ahsan M, Sengupta S, Safdar N. What drives inappropriate antibiotic dispensing? A mixed-methods study of pharmacy employee perspectives in Haryana, India. BMJ Open. 2017;7(3):1–8.

Phare M, Rose M, Sally L. Regulating private drug outlets in dar es - perceptions of key stakeholders. In: Söderlund N, MendozaArana P, Goudge AJ, editors. The new public/ private mix in health: exploring the changing landscape. Geneva: Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research; 2003. p. 35–46.

Cederlof C, Tomson G. Private pharmacies and the health sector reform in developing countries - professional and commercial highlights. J Soc Adm Pharm. 1995;12(3):101–11.

The World Bank. Physicians (per 10000 population). 2014. Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.MED.PHYS.ZS?end=2014&locations=AU-IN-LK-US-GB&start=1960&view=chart. Accessed 15 Aug 2018.

Ung E, Czarniak P, Sunderland B, Parsons R, Hoti K. Assessing pharmacists’ readiness to prescribe oral antibiotics for limited infections using a case-vignette technique. Int J Clin Pharm. 2017;39(1):61–9.

Bin Abdulhak AA, Altannir MA, Almansor MA, Almohaya MS, Onazi AS, Marei MA, et al. Non prescribed sale of antibiotics in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: a cross sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:538.

do TT N, Chuc NT, Hoa NP, Hoa NQ, Nguyen NT, Loan HT, et al. Antibiotic sales in rural and urban pharmacies in northern Vietnam: an observational study. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2014;15(1):6.

Guinovart MC, Figueras A, Llor C. Selling antimicrobials without prescription • far beyond an administrative problem. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2018;36(5):290–2.

Ayele AA, Mekuria AB, Tegegn HG, Gebresillassie BM, Mekonnen AB, Erku DA. Management of minor ailments in a community pharmacy setting: findings from simulated visits and qualitative study in Gondar town, Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2018;13(1):e0190583.

Wachter DA, Joshi MP, Rimal B. Antibiotic dispensing by drug retailers in Kathmandu, Nepal. Tropical Med Int Health. 1999;4(11):782–8.

Viberg N, Tomson G, Mujinja P, Lundborg CS. The role of the pharmacist–voices from nine african countries. Pharm World Sci. 2007;29(1):25–33.

Miller R, Goodman C. Performance of retail pharmacies in low- and middle-income asian settings: a systematic review. Policy Plan. 2016;31(7):940–53.

Zawahir S, Lekamwasam S, Aslani P. Antibiotic dispensing practice in sri lankan community pharmacies: a simulated client study. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2018.07.019.

Shet A, Sundaresan S, Forsberg BC. Pharmacy-based dispensing of antimicrobial agents without prescription in India: appropriateness and cost burden in the private sector. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2015;4:1–7.

Watson MC, Skelton JR, Bond CM, Croft P, Wiskin CM, Grimshaw JM, et al. Simulated patients in the community pharmacy setting. Using simulated patients to measure practice in the community pharmacy setting. Pharm World Sci. 2004;26(1):32–7.

Norris P. Reasons why mystery shopping is a useful and justifiable research method. Pharm J. 2004;272(7303):746–7.

Caamano F, Ruano A, Figueiras A, Gestal-Otero JJ. Data collection methods for analyzing the quality of the dispensing in pharmacies. Pharm World Sci. 2002;24(6):217–23.

Llor C, Cots JM. The sale of antibiotics without prescription in pharmacies in catalonia, Spain. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48(10):1345–9.

NMRA. Pharmacy directory. National Medicine Regulatory Authority, 120, Noris cannel Road, Colombo 10. 2016. Available from: http://nmra.gov.lk/index.php?option=com_pharmacy&Itemid=126&lang=en. Accessed 10 Oct 2016.

Garner M, Watson MC. Using linguistic analysis to explore medicine counter assistants’ communication during consultations for nonprescription medicines. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;65(1):51–7.

Gilbert A, Benrimoj SI, Crampton M, Quintrell N. Standards for the provision of pharmacist-only and pharmacy medicines. Aust J Pharm. 1998;79(940):820.

Wolffers I. Drug information and sale practices in some pharmacies of Colombo, Sri Lanka. Soc Sci Med. 1987;25(3):319–21.

Erku DA, Mekuria AB, Surur AS, Gebresillassie BM. Extent of dispensing prescription-only medications without a prescription in community drug retail outlets in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: a simulated-patient study. Drug, Healthcare and Patient Safety. 2016;8:65–70.

Puspitasari HP, Faturrohmah A, Hermansyah A. Do indonesian community pharmacy workers respond to antibiotics requests appropriately? Tropical Med Int Health. 2011;16(7):840–6.

Zawahir S, Lakmali N, Dhakshila N. Pharmacy practice in sri lanka. In: Ahmed F, Ibrahim. M, Wertheimer. A, editors. Pharmacy practice in developing countries: Achievements and challenges. 1. 1 ed: ELSEVIER; 2016. p. 79-94.

Huttner B, Consortium C, consortium C. Characteristics and outcomes of public campaigns aimed at improving the use of antibiotics in outpatients in high-income countries. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10(1):17–31.

Robinson J. Antibiotics for the common cold—do they work? Evid-Based Child Health Cochr Rev J. 2013;8(5):1512–3.

Okeke IN, Laxminarayan R, Bhutta ZA, Duse AG, Jenkins P, O'Brien TF, et al. Antimicrobial resistance in developing countries. Part i: recent trends and current status. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5(8):481–93.

Willison JD, Muzzin JL. Workload, data gathering, and quality of community pharmacistsʼ advice. Med Care. 1995;33(1):29–40.

Zaidi AKM, Awasthi S, de Silva HJ. Burden of infectious diseases in South Asia. BMJ. 2004;328(7443):811–5.

Foxman B. Urinary tract infection syndromes: occurrence, recurrence, bacteriology, risk factors, and disease burden. Infect Dis Clin. 2014;28(1):1–13.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge following people M. Bushell, P.D.U. Pavithra, Y.M.C.T. Kumara, H.M.K.G.M.C.Senarathne, S.A.T.Opatha, J.M.Dhanuka.H.Jayasundara, L.L. Sandamali, L.A.G.N.D. Liyana Arachchi, H.L.H.A. Gunadasa, R.M. Priyangika, M. Senadheera, M.D.R. Amarasinghe, H.P.D. Madhushani, W.P.D. Kaushalya, M.D. Manamperi and W.D.M. Samanthika for their contribution in conducting and publishing this research. We are also thankful to the pharmacies that participated in the study.

Funding

This study was not funded by any specific grants; however, the data collection was partially supported by the postgraduate research support scheme (PRSS) and research funds of the Faculty of Pharmacy, the University of Sydney.

Availability of data and materials

All relevant data are included in the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SZ, SL and PA designed the research study. SZ analysed all the data and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. PA and SL contributed significantly to all drafts of the manuscript and its final version. All authors have read and agreed with the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the local ethics review committee, faculty of medicine, University of Ruhuna Sri Lanka (Reference number 16.11.2016:3.1). Prior informed written consent was obtained for pseudo-patient visits and audio recording of the interaction during the self-reported survey phase of the research project. The processing of participants’ personal data was anonymised, and all data were kept confidential, including personal identifiers complied with local data protection legislations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Zawahir, S., Lekamwasam, S. & Aslani, P. Community pharmacy staff’s response to symptoms of common infections: a pseudo-patient study. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 8, 60 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13756-019-0510-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13756-019-0510-x