Abstract

Background

Non-prescription access to antimicrobials is common, and self-prescribing is increasingly popular in Russian society. The aim of this study was to assess the attitudes of community pharmacists regarding antibiotic use and self-medication.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional study from September-December 2015 of community pharmacists in the Saint-Petersburg and Leningrad region, Russia. A self-administered questionnaire was used to assess antibiotic use and self-medication practices. The data were analysed using logistic regression and Pearson chi-squared tests.

Results

Of the 316 pharmacists (77.07%) who completed the questionnaire, 230 (72.8%) self-medicated with antibiotics. Antibiotics were mostly used to self-treat upper (53.3%) and lower respiratory tract infections (19.3%), relying on their own knowledge (81.5%), previous treatment experience (49%) and patients’ prescriptions (17%). The most commonly used antibiotics were macrolides (33.2%). Characteristics such as age, education and experience were related to antibiotic use and self-medication.

Conclusions

The study confirmed that self-prescription of antibiotics is a common practice amongst pharmacists in Saint Petersburg and also identified personal and professional characteristics of pharmacists strongly associated with self-medication.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In the past decade, the worldwide consumption of antibiotic drugs has increased substantially. Russia, along with Brazil, India, China, and South Africa, accounts for 76% of the overall increase in the global consumption of antibiotics [1]. Non-prescription access to antimicrobials, including antituberculosis drugs, is common, and self-prescribing has become increasingly popular in Russian society [2]. Conditions that require prescriptions for the dispensation of antibiotics are not explicitly defined in the legislation of the Russian Federation. This leads to arbitrary attitudes toward antibiotics among health professionals, especially pharmacists, whose primary role in dispensing over-the-counter antibiotics offsets with imperfect enforcement. Moreover, in an environment with a relatively low level of public trust in physicians and the lack of formal need for a doctor’s office visit, pharmacists have become the main alternative for patients not only in providing proper counselling but in functioning as a substitute for physicians in antibiotic selection, the administration of antibiotic regimens and the course of therapy [3].

The purpose of this article is to explore pharmacists’ approach to antibiotic treatment, including antibiotic choice, and to assess their knowledge of and attitudes toward antimicrobial resistance to define ways to prevent the practice of dispensation without prescriptions.

Methods

Study setting and population

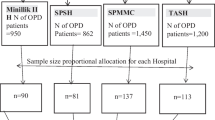

The study was conducted from September-December 2015 in community pharmacies in the Saint Petersburg and Leningrad region, Russia. The sample comprised 63 pharmacies and 316 pharmacists from one of the largest pharmacy chains.

Measures

A self-administered questionnaire was adapted from a previous study conducted by our research group [4]. The questionnaire included close-ended (yes/no, single choice and multiple choice) and open-ended questions (an English translation is available in Additional file 1). Denoting the sixteen questions from Q1 to Q16, they can be grouped into the following categories: attitudes and behaviours towards antibiotic use and self-medication (Q1, Q2, Q3, Q7, Q11, Q12); information on the types of involved diseases, antibiotics and side effects (Q3 partially, Q4, Q9); knowledge of antibiotic use and resistance and source of antibiotic knowledge (Q5, Q6, Q8, Q10); and personal and professional information (Q13 – Q16).

Statistical analysis

To evaluate the influence of attitudes, behaviour, knowledge and demographics on self-medication with antibiotics, univariate logistic regression analyses were performed. Self-medication occurred when the respondents indicated that they purchased antibiotics for themselves (or their children) without a physician’s prescription but based on their own knowledge or on recommendations of friends (see part two of Q2). This defined the dichotomous dependent variable. The independent variables were, respectively, the outcomes of questions Q1, Q3, Q5, Q6, Q11, Q12, Q13, Q14, Q15 and Q16. We did not include variables related to information on the types of involved diseases, antibiotics and side effects (Q3, Q4, Q9), as they contained too many outcomes, and we also did not include variables with essentially only one outcome (Q8, Q10, Q13). For most of the included questions, all respondents provided answers; however, questions Q14 to Q16 had a percentage of missing values of 0.3% (1 answer) each, and Q7 was missing 3.2% (10 answers). In a few cases, multiple answers to the same question were provided; the highest score (e.g., highest education, highest age, best knowledge) was then used for the regression analysis. For question Q6, however, there were too many multiple answers to address using this approach. Therefore, Q6 was divided into three separate dichotomous variables with outcomes yes or no: Q6a, Q6b and Q6c.

The results of the regression models were presented as the estimated odds ratios and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals. Hypothesis tests for regression coefficients (Wald tests) were performed and expressed with p values at a significance level of α = 0.05.

We also tested for associations between demographic characteristics (Q14 – Q16) and the remaining independent variables. We used Pearson chi-squared tests with p values at a significance level of α = 0.05. To avoid low expectation counts, the outcomes of Q14 – Q16 were recategorized (in clear ways) into two groups. PASW statistical software was used for all analyses (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA, version 18.0).

Results

Of the 410 questionnaires distributed, 316 (77.07%) were completed and collected.

The main demographic characteristics of the respondents are summarized in 1. The sample was predominantly female, which is rather typical for Russian pharmacies. The mean age of the respondents was 39.3 years, and almost half of them were 41-60 years. The vast majority of pharmacists had a baccalaureate degree, and nearly half of them had 10 years of experience of working in a pharmacy. Table 1 shows that slightly more than two-thirds of the pharmacists self-medicated.

Other characteristics of the sample that are not displayed in Table 1 are as follows.

About three-quarters of the respondents (72.8%) self-medicated when they were sick. The highest prevalence of self-medication was reported for the age group of those 41-60 years old (45.3%). Young and middle-aged respondents (31-40 years) were more responsible: 22.8% of them went to the doctor, and 20.6% self-medicated. However, the logistic regression analysis, which is addressed in more detail later, did not reveal statistically significant higher probabilities of self-medication for any of these age groups. Only 33% purchased antibiotics using a doctor’s prescription. More than half (61%) of the respondents visited a doctor for an examination and received a prescription from time to time, and 6% of staff pharmacists never bought antibiotics from a prescription. The respondents who did not visit or rarely visited a doctor for prescriptions bought antibiotics based on their knowledge (81.5%) or their friends’ advice (5.0%); analyses of their experiences with previous treatment (49.0%); and prescriptions provided by pharmacy customers (17.0%). Only a small number of respondents (8.0%) considered cost to a significant degree when purchasing medicine.

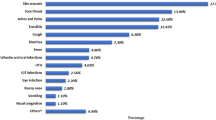

Antibiotics were mostly used to self-treat upper and low respiratory tract infections (53.3% and 19.3%, respectively). Other conditions addressed with self-medication were dental problems, urogenital infections and respiratory inflammation.

The most commonly used antibiotics were macrolides (33.2%). Azithromycin was predominant in this group and accounted for 81.1% of all self-prescriptions. Semi-synthetic penicillins (30.9%) and fluoroquinolones (15.2%) were other most frequently used groups, followed by tetracyclines (7.8%), second-generation cephalosporins (5.5%), lincosamides (5.4%) and aminoglycosides (2.0%).

The main source of information regarding antibiotics was training sessions (43.2%), patient information leaflets (30.1%) and specific literature (26.7%). More than half of the respondents (66.8%) took their antibiotics according to the information on the leaflet, one-third (31%) took antibiotics in line with their physician’s prescriptions, and the rest (2.2%) stopped using the antibiotic early when their symptoms decreased.

Oral dosage was the most preferred form of antibiotics.

Table 2 shows the impact of pharmacists’ attitudes, behaviour and knowledge on self-medication with antibiotics.

The following associations were found to be statistically significant. When feeling ill, those who consulted a physician had a lower probability (OR 0.41) of self-medication than those who self-medicated, which is self-evident. Concerning the way antibiotics were used, those acting according to patient leaflets had a higher chance (OR 2.09) of self-medication than those who used antibiotics as prescribed by the physician. Interestingly, pharmacists who did not obtain new information on antibiotics through educational paths or specific literature exhibited a substantially decreased probability of self-medication (OR 0.57 and OR 0.44, respectively). Although not displayed in Table 2, the logistic regression analysis indicated a strong association of self-medication with all levels of education compared to those with basic (non-pharmaceutical) vocational education, with the following odds ratios: higher pharmaceutical (OR 5.201, CI 95% 1.87–14.42), other higher education (OR 3.781, CI 95% 1.12 -12.79) and vocational pharmaceutical (OR 3.613, CI 95% 1.36–9.59).

The outcomes of questions Q8 (knowledge about side effects), Q10 (knowledge about influence on normal flora) and Q13 (gender) were essentially identical (up to less than one percent) for all respondents. This similarity is explained by the fact that the respondents were with a common pharmaceutical background and 98.73% of the respondents were females.

Pearson chi-squared tests revealed no association between personal characteristics (age, education and experience) and self-medication or antibiotic use (Table 3). By contrast, variables related to the source of new information about antibiotics were shown to be significantly associated with personal characteristics.

Discussion

The results of our study show that the practice of self-prescribing antimicrobials is extremely popular amongst pharmacists in Saint Petersburg. We suggest that the main contributing factor of this high prevalence is pharmacists’ easy access to antibiotics, since a prescription for the dispensed antibiotics is neither required nor controlled by authorities during inspections.

Data on outpatient antibiotic use reported by the European Surveillance of Antimicrobial Consumption suggested that in 2009, Russia was the third largest outpatient consumer of antibiotics in Europe when consumption was expressed as the number of packages per 1000 inhabitants per day [5].

Another study by Stratchounski et al. also confirmed that the Russian population is inclined to stock antibiotics in home medicine cabinets for further uncontrolled and unsupervised use [6].

While Russian physicians are aware of antibiotic resistance and are concerned by the over-the-counter sale of antibiotics [7], pharmacists promote an inappropriate use of medications by over-the-counter dispensation. This finding can be explained by the lack of a culture in which drugs are dispensed/purchased strictly based on prescriptions. Physicians often do not write prescriptions or they provide their recommendations, including the use of antibacterial drugs, on a regular sheet of paper that may, in the best case, have a physician’s seal.

Our findings indicate that antibiotics were commonly used by pharmacists to treat upper respiratory tract infections, which raises concern regarding the potential misbelief that antibiotics can treat and eradicate infections regardless of its origin [8], as well as a lack of professional knowledge of antibiotics that largely do not act on acute cough and colds [9]. Nevertheless, the results showed that educational strategies aimed at improving professional knowledge through training sessions or specific literature could have an undesired effect on pharmacists’ intention to self-medicate. Some pharmacists explained this finding by saying that participating in trainings and receiving additional information about medicines, especially from medical representatives of drug companies, contributes to improving their professional skills and saves time because it removes the need to visit a doctor.

The most popular group of antibiotics used by the respondents was macrolides. In contrast, a study on the outpatient use of systemic antimicrobials in 24 different regions of Russia reported that in 23 regions (including Saint Petersburg), broad-spectrum penicillins were the most frequently used antimicrobials. It can be assumed that there is a significant difference in the outpatient consumption of systemic antimicrobials in different regions of Russia [10]. In some regions, older agents with unfavourable safety profiles are widely administered, whereas in other regions, newer agents are used more frequently.

Diseases such as tuberculosis, gonorrhoea, malaria and childhood ear infections are now more difficult to treat than they were a few decades ago [11]. High levels of resistance to ciprofloxacin, penicillin G, azithromycin, spectinomycin and carbapenems have been reported in Russia, as a potential result of the inappropriate use of antimicrobials [12, 13].

The widespread practice of self-medication in Russia is a result of the insufficient coverage of drug programmes and the existing problems with access to medical care. The absence of a medication reimbursement system, meaning medicines remain out-of-pocket payments, is another reason for self-medication [14], significantly affecting the prices of medicines and their availability to the public [15]. In Russia, only predetermined categories of the population receive free medication within the ONLS (Population Drug Coverage) and DLO (Extensive Drug Coverage) programmes. However, it is rather difficult for patients to obtain preferred prescriptions, as the procedure for issuing prescriptions is time-consuming and pharmacies have insufficient quantities of medicine (deficit, supply disruptions).

This study is limited by the fact that the data were self-reported, and there is thus a possibility that the participants over-reported socially desirable behaviours or under-reported socially undesirable behaviours. There were no mechanisms that objectively assessed the honesty of the participants’ answers to the survey questions. The absence of identifying data on the questionnaire sheets and the confidential nature of the study would tend to minimize this bias.

The role of pharmacists in encouraging the prudent use of antimicrobials is clearly vital. However, the practice of dispensing non-prescribed antibiotics continues to be widespread in some European countries [16–18]. Other research should focus on finding the causes of this condition. An option is to evaluate the knowledge and attitudes of pharmacists towards the antibiotic resistance and the basic principles of antibiotic therapy. Similarly, this could be an analogy with the project conducted among the Czech pharmacists, whose attitudes towards the use of generic substitution significantly reflected the level of the knowledge on generic medications [19].

Conclusions

Pharmacy employees must understand the rules, orders, and other relevant information on how to dispense antibiotics. However, most of these pharmacists do not follow these regulations. It is suggested that a well-planned, organized and structured educational programme for doctors and pharmacists should be implemented to improve the appropriate use of antibiotics.

References

Van Boeckel TP, Gandra S, Ashok A, Caudron Q, Grenfell BT, Levin SA, et al. Global antibiotic consumption 2000 to 2010: an analysis of national pharmaceutical sales data. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14:742–50.

Balabanova Y, Fedorin I, Kuznetsov S, Graham C, Ruddy M, Atun R, et al. Antimicrobial prescribing patterns for respiratory diseases including tuberculosis in Russia: a possible role in drug resistance? J Antimicrob Chemother. 2004;54:673–9.

Dyachenko SV. Pharmacoepidemiological principles of antimicrobial therapy of prevalent diseases. Khabarovsk: SEI HPE FESMU; 2010.

Belkina T, Al Warafi A, Hussein Eltom E, Tadjieva N, Kubena A, Vlcek J. Antibiotic use and knowledge in the community of Yemen, Saudi Arabia, and Uzbekistan. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2014;8:424–9.

Adriaenssens N, Coenen S, Versporten A, Muller A, Minalu G, Faes C, et al. European Surveillance of Antimicrobial Consumption (ESAC): outpatient antibiotic use in Europe (1997-2009). J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66 Suppl 6:vi3–vi12.

Stratchounski LS, Andreeva IV, Ratchina SA, Galkin DV, Petrotchenkova NA, Demin AA, et al. The inventory of antibiotics in Russian home medicine cabinets. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:498–505.

Jaruseviciene L, Radzeviciene Jurgute R, Bjerrum L, Jurgutis A, Jarusevicius G, Lazarus JV. Enabling factors for antibiotic prescribing for upper respiratory tract infections: perspectives of Lithuanian and Russian general practitioners. Ups J Med Sci. 2013;118:98–104.

Abasaeed A, Vlcek J, Abuelkhair M, Kubena A. Self-medication with antibiotics by the community of Abu Dhabi Emirate, United Arab Emirates. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2009;3:491–7.

McNulty CA, Boyle P, Nichols T, Clappison P, Davey P. Don’t wear me out - the public’s knowledge of and attitude to antibiotic use. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;59:727–38.

Rachina SA, Fokin AA, Ishmukhametov AA, Denisova MN. Analysis of Outpatient Use of Systemic Antimicrobials in Different Regions of Russia. Clin Microbiol Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;10:60–9. In Russian.

Antimicrobial (Drug) Resistance. The Problem of Antimicrobial Resistance. National institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. April 2006. Available: http://www.csus.edu/indiv/r/rogersa/bio139/weeklynewsarticles139/week2.pdf. Accessed 2 Mar 2016.

Kubanova A, Kubanov A, Frigo N, Solomka V, Semina V, Vorobyev D, et al. Russian gonococcal antimicrobial susceptibility programme (RU-GASP)--resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae during 2009-2012 and NG-MAST genotypes in 2011 and 2012. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:342.

Edelstein MV, Skleenova EN, Shevchenko OV, D’souza JW, Tapalski DV, Azizov IS, et al. Spread of extensively resistant VIM-2-positive ST235 Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Russia: a longitudinal epidemiological and clinical study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:867–76.

Versporten A, Bolokhovets G, Ghazaryan L, Abilova V, Pyshnik G, Spasojevic T, et al. Antibiotic use in eastern Europe: a cross-national database study in coordination with the WHO Regional Office for Europe. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14:381–7.

Federal Antimonopoly Service. Results of the assessment of pharmaceuticals affordability on basis of the analysis of consumer prices and price setting for pharmaceuticals in the Russian Federation (Federal subjects included) and on comparable markets of other countries, comprising the CIS, European Union and BRICS. Department of Control over Social Sphere and Commerce. 2013. Available: http://en.fas.gov.ru/upload/other/Results%20of%20the%20Assessment%20of%20Pharmaceuticals%20Affordability.pdf. Accessed 2 Mar 2016.

Zapata-Cachafeiro M, González-González C, Váquez-Lago JM, López-Vázquez P, López-Durán A, Smyth E, et al. Determinants of antibiotic dispensing without a medical prescription: a cross-sectional study in the north of Spain. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2014;69:3156–60.

Roque F, Soares S, Breitenfeld L, Gonzalez-Gonzalez C, Figueiras A, Herdeiro MT. Portuguese community pharmacists’ attitudes to and knowledge of antibiotic misuse: questionnaire development and reliability. PLoS One. 2014;9:e90470.

Marković-Peković V, Grubiša N. Self-medication with antibiotics in the Republic of Srpska community pharmacies: pharmacy staff behavior. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2012;21:1130–3.

Maly J, Dosedel M, Kubena A, Vlcek J. Analysis of pharmacists’ opinions, attitudes and experiences with generic drugs and generic substitution in the Czech Republic. Acta Pol Pharm. 2013;70(5):923–31.

Acknowledgements

We warmly thank all the pharmacists who took part in this study.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the Charles University in Prague (SVV 260 187). The funding body had no role in the design, collection, analysis or interpretation of this study. Grant funds were used for the manuscript editing service before its submission.

Availability of data and materials

RAW data of this study are available on request from the archive of Charles University, Faculty of Pharmacy in Hradec Kralove.

Authors’ contributions

TB was the principal investigator responsible for the design and conception of the study and the collection and interpretation of data and wrote the manuscript. ND participated in the study design, coordination, and data collection and drafted the manuscript. JK participated in the study design, coordination, and data collection and drafted the manuscript. JDT conducted the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. JV participated in the study design and coordination and the review of the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

In accordance with Russian regulations, non-interventional studies do not need the approval of the Ethics Committee at the Federal Agency on quality control, efficiency, safety of medicines. The regulations establish control on clinical trials of a medicinal product for medical use by local Ethics Committees covered by the Federal Law on Circulation of Medicines № 61-FZ of 12 April 2010, which does not contain special requirements for non-interventional studies. The National Standard of “Good Clinical Practice” (GOST R 52379-2005) primarily relates to prospective clinical trials. Our study did not imply the clinical trial of a medicinal product and did not require any special approval of the national competent authorities. The study was, however, approved by the Ethical Committee of Charles University in Prague. № Vlcek_J_12.01.15. The pharmacists were informed about the possible use of anonymous data when evaluating the results of the observational study. Oral informed consent was obtained from all pharmacists who participated in the focus group study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Questionnaire “Use of antibiotics by pharmacy employees”. (DOCX 17 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Belkina, T., Duvanova, N., Karbovskaja, J. et al. Antibiotic use practices of pharmacy staff: a cross-sectional study in Saint Petersburg, the Russian Federation. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol 18, 11 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40360-017-0116-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40360-017-0116-y