Abstract

Ecological stoichiometry is an important indicator presenting multiple elements balance in agro-ecosystems. However, information on microbial communities and nutrient stoichiometry in soil aggregate fractions under different croplands (rice, maize, and soybean fields) remains limited. Thus, this study investigated water-stable aggregate structure and their internal nutrient stoichiometry under different croplands and ascertain their interaction mechanism with microbial communities. The results showed that no significant difference on the carbon-to-nitrogen ratio (C:N) in soil aggregate fractions was observed, while the carbon-to-phosphorus ratio (C:P) and the nitrogen-to-phosphorus ratio (N:P) were ranked as rice field > maize field > soybean field, and were higher in mega-aggregates (ME, > 1 mm). General fatty acid methyl ester (FAME), Gram-positive bacteria (G+), and Gram-negative bacteria (G−) were predominant microbial communities in all croplands and tented to condense into coarse-aggregates. Redundancy analysis (RDA) demonstrated that N:P ratio was primary environmental controls on the distribution of soil microorganisms. In the Sanjiang Plain, N was the nutrient element limiting agro-ecosystem productivity, and rice cultivation is expected to improve the N-limited nutrient status.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Soil carbon (C), as an important soil component, greatly influences soil structure, fertility, and water-holding capacity, thus presenting a critical effect on the function of agro-ecosystems (Liu et al. 2017; Liu et al. 2018). Similar to C, soil nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P) have also received considerable attentions because they are two primary elements regulating plant growth (Delgado-Baquerizo et al. 2018; Wang et al. 2018). Generally, C, N, and P cycles are closely coupled through soil organic matter (SOM) decomposition and ecosystem respiration due to the constrained proportions of these elements required by microorganisms (Wang et al. 2012; Tian et al. 2018). Therefore, ecological stoichiometry is a serviceable tool to understand the dynamics and function of terrestrial ecosystems and has emerged as a useful method to indicate the nutrient-limitation status (Tessier and Raynal 2003; Zeng et al. 2017).

Different croplands are closely related to biomass production and biogeochemical cycles (Zhang et al. 2019). Difference in water incubation of cultivated fields (rice field: flooding stress; maize and soybean fields: drought stress) and source sink of nutrients (fertilization and crop harvesting) among croplands is considered as main reasons that affect soil nutrient content and stoichiometry (Ahmad et al. 2017). For example, Wang et al. (2014) demonstrated that the more flooded soils have more fine texture because fine practices have more time to sediment, making that a decrease in C, N, and P release. Additionally, Gao et al. (2014) proved that plant type and management practices were closely related to soil C accumulation and nutrient dynamics. Further, Stevenson et al. (2016) indicated that cropland conversion will significantly change C:P and N:P, but not C:N. However, the coupling mechanism among C, N, and P across different croplands is still somewhat uncertain.

As essential building blocks of soil structure (Guber et al. 2005), soil aggregates resistance to the potential for soil organic carbon (SOC) sequestration and the supply of nutrients (Arai et al. 2013; Ahmad et al. 2017). Additionally, soil microbial communities play critical roles in dominating the formation of soil aggregates, the fixation of C and N (Zhang et al. 2019), and the coupling correlations among C, N, and P in turn affect the distribution of microbial communities in soil aggregate fractions (Cleveland and Liptzin 2007). Previous researches indicated that bacterial cells and fungal hyphae can provide temporary cementing agents for the aggregation of fine aggregates into coarse aggregates, thereby decreasing the loss risk of nutrient elements with soil erosion and surface runoff (Li et al. 2016; Garland et al. 2018), whereas the redistribution patterns of microbial communities and ecological stoichiometry in soil aggregate fractions under different croplands have been explored only preliminarily. Therefore, conducting a research on the interaction between soil microorganisms and nutrient stoichiometry related to soil aggregate structure under different croplands has scientific significance for better understanding the biogeochemical cycle mechanism of C, N, and P.

To date, despite considerable efforts have been directed at understanding how microbial communities and nutrient stoichiometry function together and how agricultural management practices impact these components and coupling correlation as well as their ability to function in processes important to agro-ecosystems’ productivity and environmental quality (Buyer and Sasser 2012; Maul et al. 2014; Buyer et al. 2019), the accurate essence of the redistribution of aggregate-related nutrient stoichiometry on changes in microbial communities under different croplands remains poorly understood. To address these issues, the central objectives of this study are threefold: (1) to illustrate the proportion and stability of soil aggregate fractions under different croplands; (2) to ascertain aggregate-related stoichiometrical characteristics among C, N, and P as an action of microbial communities; and (3) to confirm the optimal tillage method for increasing crop productivity and improving nutrient-limiting status in the Sanjiang Plain. Expected results may provide fundamental insights into understanding the biogeochemical cycle of nutrient elements and maintaining the sustainable development of cultivated land in the Sanjiang Plain.

Materials and methods

Sampling location

Croplands, including rice, maize, and soybean fields, are located in the Sanjiang Plain (45° 01′ 05′′–48° 28′ 56′′ N, 130° 13′ 10′′–135° 05′ 26′′ E), which experiences a temperate continental monsoon climate with mean annual precipitation of 565–600 mm, 60% concentrated in June to August, and average temperatures ranging from – 21 °C in January to 22 °C in July (Yan et al. 2017). Experimental rice and soybean fields are separated on both sides of a drainage ditch and are less than 2000 m away from maize field. Therefore, selected croplands have similar hydrothermal conditions, thereby reducing the influence of natural factors on elemental biogeochemical cycle. Furthermore, flat topography in the Sanjiang Plain avoids nutrient migration in horizontal direction due to surface water flow.

In mid-October 2017, 3 quadrats (3 × 3 m) were randomly distributed in each cropland. Five soil cores (0–15 cm) were collected in a diagonal line and pooled together as one composite sample. According to the Chinese Soil Classification System, the soil is characterized as swamp soil. The chemical properties of detected soil samples were reported in our previous study (Cui et al. 2019).

Soil aggregate segregation

Soil aggregate fractions were separated using a wet-sieving method (Garland et al. 2018). Well-preserved soil samples were air-dried to an approximately 10% gravimetric water content (Six et al. 2000), then broken into 1-cm blocks along its natural structure and placed on the top of a nest of sieves (1, 0.25, and 0.053 mm). Distilled water was added to soak soil particles for 10 min. Sieving consisted of raising and lowering at an oscillation rate of 50 times/min for 2 min. Subsequently, the residuum in sieves and suspension was transferred into 250-mL beakers and oven-dried at 60 °C to a constant weight.

The following parameters, including the mean weight diameter (MWD), geometric mean diameter (GMD), mean weight specific surface area (MWSSA), and fractal dimension (D) were measured to investigate soil aggregate stability under different croplands. MWD, GMD, and D reflect the water erosion resistance of soil aggregates. The higher the MWD and GMD, the more stable the soil aggregates, while D does the opposite. A higher MWSSA indicates the stronger adsorption capacity of soil aggregates to nutrients.

where Di represents the arithmetic mean diameter of soil aggregates with a grain-size of i. Dmax represents the arithmetic mean diameter of soil aggregates with maximum grain-size. Mi represents the mass proportion of soil aggregates with a grain-size of i. Mo represents the total weight of soil particles (Luo et al. 2018).

Phospholipid fatty acid (PLFA) analysis

Microbial communities were determined through PLFA analysis (Buyer et al. 2019). Briefly, freeze-dried sample (8.00 g) was used for lipid phosphate extraction with one phase chloroform-methanol-phosphate buffer solvent in a ratio of 2:1:0.8. Fatty acid identifications were confirmed on a gas chromatography-mass spectrometer and analyzed using the PLFAD1 method in the Sherlock software (MIDI Inc., Newark, DE, USA). PLFAs were characterized as General FAME, Gram-positive bacteria (G+), Gram-negative bacteria (G−), arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AM fungi), fungi, actinomycetes, anaerobe, and eukaryote using the software from the Microbial Identification System (Microbial ID, Inc., Newark, DE) (Buyer and Sasser 2012; Chang et al. 2017).

The following parameters, including the richness index (S), Shannon diversity index (H), Pielou evenness index (J), and Simpson dominance index (D) were measured to identify microbial community structure under different croplands.

where Pi represents the relative abundance and calculated from the ratio between the area of corresponding peak to the sum of the areas of all the peaks considered in the chromatograms; S represents the numbers of species of PLFA identified in a sample for analysis.

Physico-chemical analysis

Air-dried soil samples were analyzed for pH and EC in a 1:10 (w/v) sediment-to-distilled water suspension with a multi-parameter probe (520 M-01A, LTD). Total nitrogen (TN) and total phosphorus (TP) were measured with a flow injection auto-analyzer (Smartchem 200, AMS/Westco, Italy). Total organic carbon (TOC) was determined through an organic carbon solid analyzer (TOC-V, SSM-5000A, Japan) based on non-dispersive infrared method. Iron (Fe) and manganese (Mn) were measured using inductively coupled plasma optical-emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) method (PQ9000, Germany). All results were reported as mean values ± standard deviation for three replicates.

Statistical analysis

Differences in elemental content associated with soil aggregate fractions were performed in SPSS Ver. 20.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) using one-way ANOVA with Duncan’s multiple range test (P < 0.05). Redundancy analysis (RDA) was implemented with the Canoco software Ver. 4.5 (Biometris-Plant Research International Wageningen, The Netherlands). All figures were generated using Origin Ver. 9.0 (Microcal, Malvern, England).

Results

Soil aggregates

There was significant difference (P < 0.5) in ME, MA, MI, and SC proportions under different croplands. ME and MA were ranked as rice field > maize field > soybean field, while MI and SC did the opposite, with a decreasing order of rice field < maize field < soybean field. In studied croplands, MWD and GMD were slightly higher in rice field compared to maize field, but were significantly higher compared to soybean field. In contrast, MWSSA and D in rice field were roughly equal to maize field and were significantly lower compared to soybean field. Abovementioned results indicate that the stability of water-stable aggregates in rice field was higher, followed by maize and soybean fields (Table 1).

Soil nutrient content and stoichiometry

TOC, TN, and TP levels showed a significant difference related to soil aggregate fractions under different croplands. TOC and TN levels ranged with values of 27.58 ± 5.70, 25.61 ± 0.78, and 16.27 ± 3.07 g/kg as well as 1802.75 ± 176.42, 1715.50 ± 94.05, and 1016.25 ± 238.60 mg/kg in rice, maize, and soybean fields, respectively, and were higher in ME compared to MA, MI, and SC. TP level ranged with values of 792.46 ± 175.97, 1052.54 ± 341.70, and 893.60 ± 24.91 mg/kg in rice, maize, and soybean fields, respectively, and no significant difference in the distribution among soil aggregate fractions was observed.

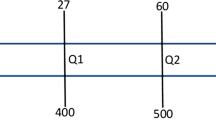

In studied croplands, C:N ratio showed no significant difference with a range of 14.05–16.40 in rice field, 14.05–15.85 in maize field, and 15.58–16.62 in soybean field, respectively. C:P and N:P ratios were in a decreasing order of rice field > maize field > soybean field, with a value of 25.72–47.32, 19.35–32.23, and 15.46–21.08 as well as 1.83–2.89, 1.38–2.03, and 0.93–1.35, respectively. For soil aggregate fractions, C:N ratio had no obvious tendency to soil aggregate fractions, whereas C:P and N:P ratios were higher in ME compared to MA, MI, and SC (Fig. 1).

Changes in nutrient stoichiometry related to soil aggregate structure under different croplands. The uppercase letters represent the difference in nutrient stoichiometry derived from different croplands, and the lowercase letters represent the difference in nutrient stoichiometry derived from soil aggregate fractions

Microbial communities

In studied croplands, PLFAs in ME, MA, MI, and SC varied within 708.11–1217.69, 973.68–1452.80, 546.19–1213.38, and 514.40–1301.36 nmol/g, respectively. General FAME, G+, G−, AM fungi, actinomycetes, and eukaryote were in a decreasing order of rice field > maize field > soybean field, accounting for 22.85–32.08%, 22.71–33.69%, 15.51–21.24%, 0.86–1.71%, 11.08–15.75%, and 4.09–15.77% of PLFAs, respectively. General FAME, G+, G−, AM fungi, and actinomycetes increased with decreasing grain size of soil aggregates in rice field, while they tended to condense in ME and MA in maize and soybean fields. Fungi and anaerobe showed an increasing order as rice field < maize field < soybean field, representing 0.19–1.94% and 0.70–2.73% of PLFAs, respectively. Fungi was higher in ME compared to MA, MI, and SC in all croplands, while anaerobe did the opposite (Fig. 2).

S, H, J, and D were significantly influenced by the type of cropland, and the difference was observed in soil aggregates with different grain sizes. H and J in ME were in a decreasing order of rice field > soybean field > maize field, while H in MA, MI, and SC showed an order as rice field ≈ soybean field > maize field. For soil aggregate fractions, D in rice field was approximately equal to that in soybean field, and both were significantly higher compared to maize field. There was no obvious change in S related to soil aggregate structure under different croplands (Table 2).

Redundancy analysis (RDA) results demonstrated that more than 86.90% of the change in soil microbial communities was explained by the combination of C:N, C:P, N:P, TOC, TN, TP, pH, EC, Fe, and Mn. The explained capacity was described as the following order: N:P (35.0%, P < 0.05) > TN (9.6%) > Fe (9.6%) > C:P (8.8%) > Mn (7.7%) > EC (7.2%) > pH (4.1%) > TOC (2.3%) > C:N (2.0%) > TP (0.6%). In RDA ordination plot, there was a significant positive correlation between Fe and eukaryote and a negative correlation between eukaryote and pH as well as C:N (Table 3, Fig. 3).

Discussion

Interaction between microbial communities and ecological stoichiometry

C level mainly depends on the decomposition rate of microorganisms, and the activity of microorganisms is restricted by N and P (Zhang et al. 2019). Therefore, soil microbial communities are closely related to the biogeochemical cycle and stoichiometric characteristic among C, N, and P (Cui et al. 2018). RDA results demonstrated that N:P ratio was primary environmental factors controlling the distribution of soil microorganisms, accounting for 35.0% of variation information on microbial communities, conforming the conclusion that N:P ratio significantly correlated with microbial biomass (Hu et al. 2019). Furthermore, soil nutrients present different preferences for soil microbial communities, which N strongly affected fungal communities, where P has a significant influence on bacterial communities (Nottingham et al. 2018), similar to our results that N as well as AM fungi and fungi contents were higher in soybean field, while there was a considerable P content as well as General FAME, G+, and G− in rice field. C:N ratio contributed less to the change in microbial communities, which can be interpreted as the fact that C and N are structural components, and their accumulation and consumption are relatively fixed (Cleveland and Liptzin 2007), which is in line with the identical C:N ratio in studied croplands. C:P and N:P ratios as well as PLFAs presented a parallel variation tendency, three of which were ranked as rice field > maize field > soybean field. Compelling reasons could be explained by the two facts: one is that the formation of microbial cells requires P-enriched phospholipid molecular as backbone and consumes a large P amount (Koerselman and Meuleman 1996); the other is that cropland soil with abundant microbial content is conductive to the conversion of organic phosphorus (Org-P) into available phosphorus (A-P), thus improving the P adsorption and utilization efficiency (Teng et al. 2018).

For soil aggregate fractions, C:P ratio showed an obvious orientation in ME, MA, MI, and SC, and there was no significant difference in C:P ratio under different croplands. Oppositely, C:P and N:P ratios in ME were higher compared to MA, MI, and SC, but no significant difference was found among the latter three aggregates. PLFAs in soil aggregates with different grain sizes presented an apparent fluctuation under different land uses. These results agree with previous findings that soil enzyme activities were significantly correlated with C:P and N:P ratios, but not with C:N ratio (Zhang et al. 2019). A reasonable explanation is that microorganisms, especially fungi, provide abundant cementing agents for the aggregation of fine aggregates into coarse aggregates (Li et al. 2016), and enhance the physical protection of coarse aggregates against C and N (Wei et al. 2014), thereby increasing C:P and N:P in ME. In view of the truth that the impact of cropland types on water-stable aggregate structure and its internal microbial communities and physiochemical properties is unclear, further research is needed to understand the importance of aggregate-related ecological stoichiometry in soil property (Xu et al. 2019).

Environmental significance of soil nutrient stoichiometry for agro-ecosystem productivity

In the Sanjiang Plain, C:N ratio was almost equal to the average of China (14.40) and the global (14.31) (Tian et al., 2018). Compared to the average of China (136.00 and 9.30) and the global (186.00 and 13.00) (Tian et al. 2018), C:P and N:P ratios in the Sanjiang Plain were significant lower. A lower N:P ratio could be explained as three facts: (1) soybean, as one of the main food crops in northeast China, has reduced the application amount of nitrogen fertilizer due to its strong nitrogen fixation ability, (2) ammonium nitrogen (NH4+−N) in soil is easily lost with surface water and is evaporated in the form of ammonia gas (NH3), and (3) the low temperature in the northeast China limits the activity of microorganisms, which in turn reduces phosphorus activity and vegetation uptake. According to the ecological theory that plant growth is N-limited at N:P ratio < 14 (Aerts and Chapin, 1999), abovementioned results indicate that N in cropland soil is relatively lower, while P does the opposite, leading to N being the primary nutrient element limiting agro-ecosystem productivity in the Sanjiang Plain.

Different croplands are an important parameter on determining the biogeochemical cycle and coupling relationship among C, N, and P (Ahmad et al. 2017). Wei et al. (2014) attributed it to the effect of different croplands on water-stable aggregate formation and structure related to SOC decomposition process and nutrient cycles in agro-ecosystems. In rice field, ME was significantly higher compared to maize and soybean fields. Additionally, ME showed a considerable N:P ratio compared to MA, MI, and SC under different croplands. Therefore, considering the regional soil texture and nutrient status, rice field is a suitable tillage method in northeast China. There is a well-known conclusion that coarse aggregates are characterized as loose texture, fine ventilation, and favorable water-holding capacity (Reichstein and Beer, 2008; Fox et al. 2018), thus increasing the sequestration of SOC and the mineralization of organic nitrogen (Org-N) and Org-P. So, higher ME in rice field may enhance agro-ecosystems’ productivity. Simultaneously, the expansion of rice cultivated area is expected to improve the N-limited nutrient status in the Sanjiang Plain due to higher N:P ratio in ME. Previous researches demonstrated that nutrients in coarse aggregates (> 0.2 mm) are mainly adsorbed on mental hydroxides, and are easily released when there is a change in oxidation-reduction potential (ORP), while that in fine aggregates (< 0.2 mm) mostly exist in organic form and only can be utilized under the action of microbial mineralization (Linquist et al. 1997; Ranatunga et al. 2013; Soinne et al. 2014). Therefore, further research efforts should focus on the influence of changes in soil aggregate structure and stability on soil nutrient availability under croplands disturbances. In addition, natural conditions under different croplands play a critical role in the carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus cycles. In the rice field, the anaerobic environment caused by flooding conditions inhibits the activity of soil microorganisms, leading to a decrease in the mineralization rate of organic carbon and the amount of carbon dioxide released by respiration, which is in line with our results that TOC in the rice field was higher in accordance with maize and soybean fields. Fertilization methods will also cause differences in the contents and eco-stoichiometric characteristics among TOC, TN, and TP. Because the soybean rhizobia have a strong nitrogen-fixing ability, and can absorb nitrogen from the air to maintain the growth of soybeans, the application amount of nitrogen fertilizer is low. This conclusion certified our results that TN in the soybean field was lower compared to the rice and maize fields.

Conclusions

Different croplands significantly influence the water-stable aggregate fractions as well as their internal microbial communities and nutrient stoichiometry. In studied croplands, the stability of water-stable aggregates in rice field was higher, followed by maize and soybean fields. C:P and N:P ratios were ranked as rice field > maize field > soybean field and were higher in coarse aggregates. General FAME, G+, and G− were predominant microbial communities and tented to condense into coarse aggregates. N:P ratio was primary environmental factors controlling the distribution of soil microorganisms. In the Sanjiang Plain, N was the nutrient element limiting agro-ecosystems’ productivity, and rice cultivation is expected to improve the N-limited nutrient status.

References

Aerts R, Chapin FS (1999) The mineral nutrition of wild plants revisited: A re-evaluation of processes and patterns. Adv Ecol Res 30:1–67.

Ahmad EH, Demisie W, Zhang M (2017) Effects of land use on concentrations and chemical forms of phosphorus in different-size aggregates. Eurasian Soil Sci 50:1435–1443

Arai M, Tayasu I, Komatsuzaki M, Uchida M, Shibata Y, Kaneko N (2013) Changes in soil aggregate carbon dynamics under no-tillage with respect to earthworm biomass revealed by radiocarbon analysis. Soil Till Res 126:42–49

Buyer JS, Sasser M (2012) High throughput phospholipid fatty acid analysis of soils. Appl Soil Ecol 61:127–130

Buyer JS, Vinyard B, Maul J, Selmer K, Lupitskyy R, Rice C, Roberts DP (2019) Combined extraction method for metabolomic and PLFA analysis of soil. Appl Soil Ecol 135:129–136

Chang CH, Szlavecz K, Buyer JS (2017) Amynthas agrestis invasion increases microbial biomass in mid-Atlantic deciduous forests. Soil Biol Biochem 114:189–199

Cleveland CC, Liptzin D (2007) C:N:P stoichiometry in soil: is there a “Redfield ratio” for the microbial biomass? Biogeochemistry 85:235–252

Cui H, Ou Y, Wang LX, Yan BX, Han L, Li YX (2019) Change in the distribution of phosphorus fractions in aggregates under different land uses: a case in Sanjiang plain, Northeast China. Int J Environ Res Public Health 16:212.

Cui YX, Fang LC, Guo XB, Wang X, Wang YQ, Li PF, Zhang YJ, Zhang XC (2018) Responses of soil microbial communities to nutrient limitation in the desert-grassland ecological transition zone. Sci Total Environ 642:45–55

Delgado-Baquerizo M, Eldridge DJ, Maestre FT, Ochoa V, Gozalo B, Reich PB, Singh BK (2018) Aridity decouples C:N:P stoichiometry across multiple trophic levels in terrestrial ecosystems. Ecosystems 21:459–468

Fox A, Ikoyi I, Torres-Sallan G, Lanigan G, Schmalenberger A, Wakelin S, Creamer R (2018) The influence of aggregate size fraction and horizon position on microbial community composition. Appl Soil Ecol 127:19–29

Gao Y, He N, Yu G, Chen W, Wang Q (2014) Long-term effects of different land use types on C, N, and P stoichiometry and storage in subtropical ecosystems: a case study in China. Ecol Eng 67:171–181

Garland G, Bunemann EK, Oberson A, Frossard E, Snapp S, Chikowo R, Six J (2018) Phosphorus cycling within soil aggregate fractions of a highly weathered tropical soil: a conceptual model. Soil Biol Biochem 116:91–98

Guber AK, Pachepsky YA, Levkovsky EV (2005) Fractal mass-size scaling of wetting soil aggregates. Ecol Model 182:317–322

Hu L, Ade L, Wu XW, Zi HB, Luo XP, Wang CT (2019) Changes in soil C:N:P stoichiometry and microbial structure along soil depth in two forest soils. Forests 10:12

Koerselman W, Meuleman AFM (1996) The vegetation N:P ratio: a new tool to detect the nature of nutrient limitation. J Appl Ecol 33:1441–1450

Li Z, Tang H, Xiao Y, Zhao H, Li Q, Ji F (2016) Factors influencing phosphorus adsorption onto sediment in a dynamic environment. J Hydro-Environ Res 10:1–11

Linquist BA, Singleton PW, Yost RS, Cassman KG (1997) Aggregate size effects on the sorption and release of phosphorus in an ultisol. Soil Sci Soc Am J 61:160–166

Liu X, Li L, Wang Q, Mu S (2018) Land-use change affects stocks and stoichiometric ratios of soil carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus in a typical agro-pastoral region of Northwest China. J Soils Sediments 18:3167–3176

Liu X, Ma J, Ma ZW, Li LH (2017) Soil nutrient contents and stoichiometry as affected by land-use in an agro-pastoral region of Northwest China. Catena 150:146–153

Luo S, Wang S, Tian L, Shi S, Xu S, Yang F, Li X, Wang Z, Tian C (2018) Aggregate-related changes in soil microbial communities under different ameliorant applications in saline-sodic soils. Geoderma 329:108–117

Maul JE, Buyer JS, Lehman RM, Culman S, Blackwood CB, Roberts DP, Zasada IA, Teasdale JR (2014) Microbial community structure and abundance in the rhizosphere and bulk soil of a tomato cropping system that includes cover crops. Appl Soil Ecol 77:42–50

Nottingham AT, Hicks LC, Ccahuana AJQ, Salinas N, Baath E, Meir P (2018) Nutrient limitations to bacterial and fungal growth during cellulose decomposition in tropical forest soils. Biol Fert Soils 54:219–228

Ranatunga TD, Reddy SS, Taylor RW (2013) Phosphorus distribution in soil aggregate size fractions in a poultry litter applied soil and potential environmental impacts. Geoderma 192:446–452

Reichstein M, Beer C (2008) Soil respiration across scales: the importance of a model–data integration framework for data interpretation. J Plant Nutr Soil Sc 171

Six J, Elliott ET, Paustian K (2000) Soil structure and soil organic matter: II. A normalized stability index and the effect of mineralogy. Soil Sci Soc Am J 64:1042–1049

Soinne H, Hovi J, Tammeorg P, Turtola E (2014) Effect of biochar on phosphorus sorption and clay soil aggregate stability. Geoderma 219-220:162–167

Stevenson BA, Sarmah AK, Smernik R, Hunter DWF, Fraser S (2016) Soil carbon characterization and nutrient ratios across land uses on two contrasting soils: their relationships to microbial biomass and function. Soil Biol Biochem 97:50–62

Teng Z, Zhu Y, Li M, Whelan MJ (2018) Microbial community composition and activity controls phosphorus transformation in rhizosphere soils of the Yeyahu wetland in Beijing, China. Sci Total Environ 628-629:1266–1277

Tessier JT, Raynal DJ (2003) Use of nitrogen to phosphorus ratios in plant tissue as an indicator of nutrient limitation and nitrogen saturation. J Appl Ecol 40:523–534

Tian LM, Zhao L, Wu XD, Fang HB, Zhao YH, Hu GJ, Yu GY, Sheng Y, Wu JC, Chen J, Wang ZW, Li WP, Zou DF, Ping CL, Shang W, Zhao YG, Zhang GL (2018) Soil moisture and texture primarily control the soil nutrient stoichiometry across the Tibetan grassland. Sci Total Environ 622:192–202

Wang H, Sterner RW, Elser JJ (2012) On the “strict homeostasis” assumption in ecological stoichiometry. Ecol Model 243:81–88

Wang L, Wang P, Sheng M, Tian J (2018) Ecological stoichiometry and environmental influencing factors of soil nutrients in the karst rocky desertification ecosystem, Southwest China. Glob Ecol Conserv 16:e00449

Wang W, Sardans J, Zeng C, Zhong C, Li Y, Peñuelas J (2014) Responses of soil nutrient concentrations and stoichiometry to different human land uses in a subtropical tidal wetland. Geoderma 232-234:459–470

Wei K, Chen ZH, Zhang XP, Liang WJ, Chen LJ (2014) Tillage effects on phosphorus composition and phosphatase activities in soil aggregates. Geoderma 217-218:37–44

Xu C, Pu L, Li J, Zhu M (2019) Effect of reclamation on C, N, and P stoichiometry in soil and soil aggregates of a coastal wetland in eastern China. J Soils Sediments 19:1215–25.

Yan F, Zhang S, Liu X, Yu L, Chen D, Yang J, Yang C, Bu K, Chang L (2017) Monitoring spatiotemporal changes of marshes in the Sanjiang plain, China. Ecol Eng 104:184–194

Zeng Q, Liu Y, Fang Y, Ma R, Lal R, An S, Huang Y (2017) Impact of vegetation restoration on plants and soil C:N:P stoichiometry on the Yunwu Mountain Reserve of China. Ecol Eng 109:92–100

Zhang Y, Li P, Liu X, Xiao L, Shi P, Zhao B (2019) Effects of farmland conversion on the stoichiometry of carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus in soil aggregates on the loess plateau of China. Geoderma 351:188–196

Acknowledgements

We thank the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 41771505, 41571480, and 41706119) and the Project of Changchun Science and Technology Plan (No. 19SS019) for funding the present work.

Funding

This research was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 41771505, 41571480, and 41706119) and the Project of Changchun Science and Technology Plan (No. 19SS019).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.X Wang is the corresponding author who designed the research. H Cui participated in writing the manuscript. All co-authors contributed in guiding the researcher and editing the manuscript. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Author’s information

L.X Wang is a professor at Northeast Institute of Geography and Agroecology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, whose research interests focus on wetland ecology and solid waste recycling. B.X Yan is a professor at Northeast Institute of Geography and Agroecology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, whose research interests focus on sewage treatment technology. A.Z Liang is a professor at Northeast Institute of Geography and Agroecology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, whose research interests focus on organic carbon cycling in black soil system. Y Ou is a research assistant at Northeast Institute of Geography and Agroecology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, whose research interests focus on remote sensing technology. D.A Lv is an engineer at Second Institute of Oceanography, Ministry of Natural Resources, whose research interests focus on soil phosphorus cycle. H Cui and Y.X Li are postgraduates, whose research interests focus on wetland ecology and solid waste recycling.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cui, H., Ou, Y., Lv, D. et al. Aggregate-related microbial communities and nutrient stoichiometry under different croplands. Ecol Process 9, 33 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13717-020-00239-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13717-020-00239-4