Abstract

This paper utilizes the 0–1 test algorithm to identify chaos in a fractional chaotic map. A fractional Burgers map is proposed by means of the Caputo-like delta difference operator. The bifurcation diagrams, phase trajectories and 0–1 test results of the fractional Burgers map are presented, respectively. This work extends the 0–1 test algorithm to the discrete fractional chaotic map.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The fractional systems have recently received increasing attention, because fractional calculus can accurately explain many realistic problems. Many important results, such as chaos and bifurcation, on the continuous fractional systems can be found in [1–7]. However, the studies on discrete fractional systems are still in their infancy, especially in chaos dynamics. Some pioneering work for the discrete fractional systems can be found in [8–14]. In addition, researchers get more interesting results for discrete fractional chaotic systems by means of [15–20]. Although many results have been presented, the identification of chaos of the fractional chaotic map is still an open topic.

Very recently, Wu et al. used Lyapunov exponents to identify chaos for the fractional chaotic map in the [21]. However, this method needs to construct the Jacobian matrix of fractional chaotic map. In fact, the construction of the Jacobi matrix is relatively tedious work in the case of a fractional map. In order to avoid the construction of a Jacobian matrix, in this paper we extend the 0–1 test algorithm [22–28] to a fractional chaotic map, which provides another reference for the study of the fractional chaotic map.

This article is structured as follows. The basic definitions of discrete fractional calculus are introduced in Sect. 2. In Sect. 3, the fractional Burgers map is obtained by means of Caputo-like delta difference. In Sect. 4, the chaotic behaviors of the fractional Burgers map are investigated. In Sect. 5, the conclusions arising from this study are summarized.

2 Preliminaries

The basic definitions of discrete fractional calculus briefly described in this section. See references [10–12] for more details. The falling \(\mathbb{N}_{a}= \{a,a+1,a+2,\ldots\} \) denotes the time scale.

Definition 1

Let \(x(t):\mathbb{N}_{a} \rightarrow\mathbb{R} \) and \(v>0\), the fractional sum of order v is defined by

where a is the starting point, \(\sigma(s)=s+1 \), and \(t^{(v)} \) is the falling function defined as \(t^{(v)}=\frac{\varGamma{(t+1)}}{\varGamma{(t+1-v)}}\).

Definition 2

For \(v>0\), the vth Caputo-like delta difference can be defined as

where \(n=[v]+1\).

Theorem 1

([13])

For the delta fractional difference equation

the equivalent discrete integral equation can be obtained as

where the initial iteration reads

Particularly, if for the initial point \(a=0\), and \(0< v<1\), Eq. (4) is rewritten by

Using \((t-\sigma(s))^{(v-1)}=\frac{\varGamma{(t-s)}}{\varGamma {(t-s-v+1)}}\), and \(s+v=j \), Eq. (6) is further simplified to

3 The fractional Burgers map and its solution

The fractional version of Burgers map is obtained by using the Caputo-like delta operator in this section.

Consider the falling Burgers map

By taking \(a=1\) and \(b=0.83\), system (8) exhibits a chaotic behavior, which is shown in Fig. 1(a). When b is further increased to 0.88, a more complex chaotic attractor is plotted in Fig. 1(b).

Based on the first-order difference operator Δ, system (8) can be rewritten as

The Caputo-like delta operator \(^{C}\Delta_{a}^{v} \) is applied to system (9), a novel fractional Burgers map is obtained as

According to Theorem 1 in Sect. 2, taking the initial point as 0, the numerical solution of system (10) is given as

4 The chaotic dynamics of fractional Burgers map

The chaos of fractional Burgers map is identified by using the recently proposed 0–1 test.

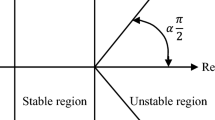

4.1 The notion of 0–1 test

Let us briefly describe the 0–1 test as follows (see [22] for more details). We consider a set of data \(\{ \phi_{k}, k= 1,2,3,\ldots\}\), which is obtained from a dynamical system. According to [22], we define a new coordinates \((p_{k},s_{k})\). Here \(p_{k}\) and \(s_{k}\) are the falling functions defined as

where

and \(c\in [\frac{\pi}{5},\frac{4\pi}{5} ]\) is a random number. Further, the mean square displacement is defined by

where \(k\ll N\), we calculate \(M_{c}(k)\) for \(k< k_{\mathrm{cut}}=\operatorname{round} (N/10)\), as recommended in the [24]. For a given c, the modified \(D_{c}(k)\) can be defined as

where \(\langle\phi \rangle\) is the mean value of \(\{ \phi _{k}, k=1,2,3,\ldots\}\), which can be calculated by

According to Eq. (15), we can define the asymptotic growth rate \(K_{c}\) by means of the correlation and regression methods, respectively. If the correlation method is used, the \(K_{c}\) is defined as

where \(\varepsilon=1,2,3, \ldots\) and \(X=(D_{c}(1),D_{c}(2),D_{c}(3), \ldots ), D_{c}(k_{\mathrm{cut}})\). If the regression method is employed, \(K_{c}\) is calculated by

Finally, according to the \(K_{c}\), we can get the median value \(K= \operatorname{median} (K_{c} )\). The idea of the 0–1 test can be described as (a) the dynamical behavior is regular when K is equal to 0; (b) the dynamical behavior is chaotic when K is equal to 1. In addition, we can also observe \((p, s)\) trajectories, the regular dynamics correspond to bounded motions whereas Brownian-like motions correspond to chaotic dynamics.

4.2 Testing for chaos

In this section, identification of chaos of the fractional Burgers map is researched by using the bifurcation diagrams, phase trajectories and 0–1 test.

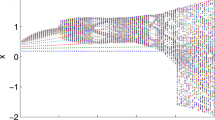

Let \(a=1\), \(v=0.9\) and b is fixed. The step size of the b is set at 0.01, in this paper, we can obtain the bifurcation diagram of system (10) versus \(b \in [ 0,1 ]\) as shown in Fig. 2(a). The K median value of the time series \(x(n)\) of system (10) versus \(b \in [ 0,1 ]\) is drawn in Fig. 2(b). Let \(b=0.9\), \(v=0.9\), and the a is fixed. The step size of the a is set at 0.01, we can obtain the bifurcation diagram of system (10) versus \(a \in [ 0,1 ]\) as shown in Fig. 3(a). The K median value of the time series \(x(n)\) of system (10) versus \(a \in [ 0,1 ]\) is drawn in Fig. 3(b). Then, let \(a=1\), \(b=1\), and the fractional over v is fixed. The step size of the v is set at 0.01, we can obtain the bifurcation diagram of system (10) versus \(v \in ( 0,1 )\) as shown in Fig. 4(a). The K median value of the time series \(x(n)\) of system (10) versus \(v \in ( 0,1 )\) is drawn in Fig. 4(b). From Figs. 2, 3 and 4, we can find that system (10) shows a different chaotic dynamics when we change the parameters b and a, and the fractional order v. From Fig. 2, system (10) implies chaotic behaviors (\((K\cong1)\)) when \(b \in [ 0.82,1 ]\). From Fig. 3, system (10) implies chaotic behaviors (\((K\cong1)\)) when \(a \in [ 0.46,1 ]\). From Fig. 4, system (10) implies chaotic behaviors (\((K\cong1)\)) when \(v \in [0.79,1 )\).

Bifurcation diagram and K median value. The bifurcation diagram (a) and K median value (b) of system (10) with \(a=1\), \(v=0.9\) versus parameter b

Bifurcation diagram and K median value. The bifurcation diagram (a) and K median value (b) of system (10) with \(b=0.9\), \(v=0.9\) versus parameter a

Bifurcation diagram and K median value. The bifurcation diagram (a) and K median value (b) of system (10) with \(a=1\), \(b=1\) versus fractional order v

In addition, the \((p,s)\) dynamics is used to further verify the chaotic dynamics of system (10). The test results are shown in Fig. 5 which shows Brownian-like trajectories. The phase trajectories and chaotic solutions corresponding to Fig. 5 are shown in Fig. 6.

The 0–1 test:\((p,s)\) dynamics. The 0–1 test: \((p,s)\) dynamics of system (10), (a) \(a=1\), \(b=0.85\) and \(v=0.9\), (b) \(a=0.7\), \(b=0.9\) and \(v=0.9\), (c) \(a=1\), \(b=1\) and \(v=0.85\), respectively

The phase portraits and chaotic solutions. The phase portraits of system (10) for (a) \(a=1\), \(b=0.85\) and \(v=0.9\), (b) \(a=0.7\), \(b=0.9\) and \(v=0.9\), (c) \(a=1\), \(b=1\) and \(v=0.85\), respectively. The chaotic solutions of system (10) for (d) \(a=1\), \(b=0.85\) and \(v=0.9\), (e) \(a=0.7\), \(b=0.9\) and \(v=0.9\), (f) \(a=1\), \(b=1\) and \(v=0.85\), respectively

Based on the analyses above, we can find that the dynamics demonstrated in the 0–1 test results are consistent with the bifurcation diagrams and phase trajectories.

Besides, system (10) exhibits many NSP (numerically stable periodic) trajectories. As an example, we take \(a=1\), \(b=1 \) and \(v=0.5\), a NSP orbit of period-4 is obtained as shown in Fig. 7(a). Figure 7(b) is the K median value of the time series \(x(n)\) of system (10). The \((p,s)\) dynamics is shown in Fig. 7(c).

The NSP trajectories. The chaotic solutions (a), K median value (b) and \((p,s)\) dynamics (c) of system (10) for \(a=1\), \(b=1\) and \(v=0.5\)

5 Conclusions

Using the bifurcation diagrams, phase trajectories and 0–1 test, the identification of chaos of the fractional Burgers map is investigated in this paper. Two remarkable results are obtained as follows. Firstly, the extremely rich dynamical behaviors of the fractional Burgers map are revealed. The fractional Burgers map presents regular motions, NSP (numerically stable periodic) orbits and chaotic behaviors when we choose the different fractional order v. Compared with the Burgers map, the fractional Burgers map enlarges the parameter space and extends the range of chaos. Secondly, this study identified chaos of the fractional Burgers map by novelly using the 0–1 test, which is different from the Lyapunov exponent method in [21]. These results show that the 0–1 test is a convenient tool to diagnose chaos in fractional chaotic map.

In fact, the system is inevitably affected by uncertain factors, such as external noise and a random parameter, therefore in further research we will focus on the identification of chaos in the stochastic fractional chaotic map.

References

Ahmad, W.M., Sprott, J.C.: Chaos in fractional-order autonomous nonlinear systems. Chaos Solitons Fractals 16, 339–351 (2003)

Grigorenko, I., Grigorenko, E.: Chaotic dynamics of the fractional Lorenz system. Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, Article ID 034101 (2003)

Li, C.G., Chen, G.: Chaos in the fractional order Chen system and its control. Chaos Solitons Fractals 22, 549–554 (2004)

Li, C.P., Peng, G.J.: Chaos in Chen’s system with a fractional order. Int. J. Difference Equ. 22, 443–450 (2004)

Peng, G.J., Jiang, Y.: Generalized projective synchronization of a class of fractional-order chaotic systems via a scalar transmitted signal. Phys. A, Stat. Mech. Appl. 372, 3963–3970 (2008)

Zhao, L.D., Hu, J.B., Fang, J.A.: Studying on the stability of fractional-order nonlinear system. Nonlinear Dyn. 70, 475–479 (2012)

Jia, H.Y., Chen, Z.Q., Xue, W.: Analysis and circuit implementation for the fractional-order Lorenz system. Acta Phys. Sin. 70, Article ID 140503 (2013)

Atici, F.M., Eloe, P.W.: A transform method in discrete fractional calculus. Int. J. Difference Equ. 2, 165–176 (2007)

Xiao, H., Ma, Y., Li, C.: Chaotic vibration in fractional maps. J. Vib. Control 20, 964–972 (2014)

Atici, F.M., Eloe, P.W.: Initial value problems in discrete fractional calculus. Proc. Am. Math. Soc. 137, 981–989 (2009)

Anastassiou, G.A.: About discrete fractional calculus with inequalities. In: Intelligent Mathematics: Computational Analysis. Springer, Berlin, pp. 575–585 (2011)

Abdeljawad, T.: On Riemann and Caputo fractional differences. Comput. Math. Appl. 62, 1602–1611 (2011)

Chen, F., Luo, X., Zhou, Y.: Existence results for nonlinear fractional difference equation. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2011, Article ID 713201 (2011)

Wu, G.C., Baleanu, D., Zeng, S.D.: Discrete chaos in fractional sine and standard maps. Phys. Lett. A 378, 484–487 (2014)

Wu, G.C., Baleanu, D.: Chaos synchronization of the discrete fractional logistic map. Signal Process. 102, 96–99 (2014)

Wu, G.C., Baleanu, D., Xie, H.P.: Discrete fractional diffusion equation of chaotic order. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 26, Article ID 1650013 (2016)

Ran, J.: Discrete chaos in a novel two-dimensional fractional chaotic map. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2018, Article ID 294 (2018)

Shukla, M.K., Sharma, B.B.: Investigation of chaos in fractional order generalized hyperchaotic Henon map. AEÜ, Int. J. Electron. Commun. 78, 265–273 (2017)

Kumar, D., Singh, J., Baleanu, D.: A new analysis of the Fornberg–Whitham equation pertaining to a fractional derivative with Mittag-Leffler-type kernel. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 133, Article ID 70 (2018)

Wu, G.C., Baleanu, D., Luo, W.: Lyapunov functions for Riemann Liouville-like fractional difference equations. Appl. Math. Comput. 314, 228–236 (2017)

Wu, G.C., Baleanu, D.: Jacobian matrix algorithm for Lyapunov exponents of the discrete fractional maps. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 22, 95–100 (2015)

Gottwald, G.A., Melbourne, I.: A new test for chaos in deterministic systems. Proc., Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 460, 603–611 (2004)

Gottwald, G.A., Melbourne, I.: On the implementation of the 0–1 test for chaos. SIAM J. Appl. Dyn. Syst. 8, 129–145 (2009)

Gottwald, G.A., Melbourne, I.: On the validity of the 0–1 test for chaos. Nonlinearity 22, 1367–1382 (2009)

Bernardini, D., Litak, G.: An overview of 0–1 test for chaos. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 38, 1433–1450 (2016)

Cafagna, D., Grassi, G.: Bifurcation and chaos in the fractional-order Chen system via a time-domain approach. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 18, 1845–1863 (2008)

Sun, K., Liu, X., Zhu, C.X.: The 0–1 test algorithm for chaos and its applications. Chin. Phys. B 19, 200–206 (2010)

Krese, B., Govekar, E.: Nonlinear analysis of laser droplet generation by means of 0–1 test for chaos. Nonlinear Dyn. 67, 2101–2109 (2012)

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the referees for their valuable comments and suggestions.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Funding

This work is supported by Guizhou Provincial Natural Science Foundation (Qian Jiao He KY Zi [2018]315).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed equally to the writing of this paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ran, J. Identification of chaos in fractional chaotic map. Adv Differ Equ 2020, 228 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-020-02688-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-020-02688-9