Abstract

This article aims to develop fractional order convolution theory to bring forth innovative methods for generating fractional Fourier transforms by having recourse to solutions for fractional difference equations. It is evident that fractional difference operators are used to formulate for finding the solutions of problems of distinct physical phenomena. While executing the fractional Fourier transforms, a new technique describing the mechanism of interaction between fractional difference equations and fractional differential equations will be introduced as h tends to zero. Moreover, by employing the theory of discrete fractional Fourier transform of fractional calculus, the modeling techniques will be improved, which would help to construct advanced equipments based on fractional transforms technology using fractional Fourier decomposition method. Numerical examples with graphs are verified and generated by MATLAB.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Miller and Ross [27], Oldham and Spanier [29], and Podlubny [31] have developed continuous fractional calculus. The discrete fractional calculus, due to its widespread applications in various branches of science and engineering, has become the object of many research works [1,2,3, 7, 14, 20]. Recently discrete delta fractional calculus has been developed by Atici and Eloe [12, 13, 15], Goodrich [21,22,23], and Holm [24]. For recent developments in the theory of discrete fractional calculus, applications of Mittag-Leffler function and fractional integral inequalities, we refer to [4,5,6, 8, 9, 16, 19, 25, 26, 32].

The integral transforms, like Mellin, Laplace, Fourier, were applied to obtain the solution of differential equations. These transforms made effectively possible to change a signal in the time domain into that in the frequency s-domain in the field of Digital Signal Processing (DSP) [34]. The more recent applications of fractional Fourier transform in X-ray models and simulations are developed in [28, 30]. In [33], the forward complex DFT, written in polar form, is given by

and it takes different labels depending on the nature of \(x[n]\). The DFT \(X(t)=\frac{1}{N}\Delta ^{-1}x(n) e^{-j2\pi tn/N}| _{0}^{N}\) follows from the basic difference identity \(\Delta ^{-1}x(t)| _{0}^{N}= \sum_{n=0}^{N-1}x(n)\) in [10]. Let ℓ be the time between two successive signals. Replacing \(\Delta ^{-1}\) by \(\Delta _{\ell }^{-1}\), integer n by real t and the sequence \(x(n)\) by a function \(x(\xi )\), we get a Generalized Discrete Fourier Transform (GDFT)

When \(h=1\) and \(h\rightarrow 0\), the GDFT becomes DFT given in (1) and FT defined as \(g(t)=\int _{-\infty }^{\infty }e ^{-j2\pi tx/N}f(t)\,dt\), respectively [11, 18].

The article is organized as follows. In Sect. 2 , the basic concepts about delta and its inverse difference operators are presented. In Sect. 3 , one dimensional fractional frequency Fourier transform is defined and its properties with numerical verification are given. In Sect. 4 , some results on convolution and fractional Fourier transform are discussed. Section 5 presents the conclusion.

2 Preliminaries

Here, we present some basic definitions, notations, and preliminaries. Let us denote by \(s_{r}^{m}\) and \(S_{r}^{m}\) the Stirling numbers of first and second kind, respectively. Denote by \(\mathbb{R}=(-\infty , \infty )\), \(L(\mathbb{R})=\) the set of all Lebesgue integrable functions on \(\mathbb{R}\). Let \(h>0,m\) be the positive integer, ν be a fraction, and ω be the frequency.

The polynomial factorial is defined by \(t_{h}^{(m)}=t(t-h)(t-2h) \cdots (t-(m-1)h)\), the relation between the polynomial and polynomial factorials is given by

Definition 2.1

Let \(u(t)\), \(t\in [0,\infty )\), be a real- or complex-valued function and \(h>0\) be a fixed shift value. Then the h-difference operator \(\Delta _{h}\) on \(u(t)\) is defined as follows:

and its infinite h-difference sum is defined by

Definition 2.2

Let \(u(t)\) and \(v(t)\) be two real-valued functions defined on \((-\infty ,\infty )\), and if \(\Delta _{h} v(t)=u(t)\), then the finite inverse principle law is given by

Definition 2.3

([17], p. 5, Definition 2.6)

For \(h>0\) and \(\nu \in R\), the falling h-polynomial factorial function is defined by

where \(k_{h}^{({0})}=1\) and \(\frac{k}{h}+1,\frac{k}{h}+1-\nu \notin \{0,-1,-2,-3,\ldots\}\), since the division at a pole yields zero.

Applying Definition 2.1, we get the modified identities as follows:

Lemma 2.4

Let \(h>0\) and \(u(t)\), \(w(t)\) be real-valued bounded functions. Then

Proof

Applying (4) on the product of two functions \(u(t)v(t)\), we get

Now the proof follows by adding and subtracting \(\frac{ u(t)v(t+h)}{h}\), then applying \(\Delta _{h}^{-1}\) on both sides. □

Lemma 2.5

Let \(t\in (-\infty , \infty )\), \(h>0\), and \(\nu >0\), then we have

Proof

The proof follows by taking \(u(t)=e^{-i\omega ^{1/ \nu }t}\) in Definition 2.1 and applying \(\Delta _{h}^{-1}\). □

Corollary 2.6

Let \(t\in (-\infty , \infty )\), \(h>0\), and \(\nu >0\), then we have

Proof

The proof follows by equation (11) and the finite inverse principle law given in (6). □

Example 2.7

For the particular values \(\nu =0.6\), \(s=0.2\), \(t=4\), \(m=2\), and \(h=3\), (12) is verified by MATLAB. The coding is given by \(3\times \operatorname{symsum}(\exp (-i \times (0.2)^{(1/0.6)}\times (4-3\times r)),r,1,2)=(3\times \exp (-i \times (0.2)^{(1/0.6)}\times 4))/(\exp (-i\times (0.2)^{(1/0.6)}\times 3)-1)-(3\times \exp (-i\times (0.2)^{(1/0.6)}\times -2))/(\exp (-i\times (0.2)^{(1/0.6)}\times 3)-1)\).

Theorem 2.8

Let \(t\in (-\infty , \infty )\) and \(h>0\). Then we have

Proof

Taking \(u(t)=t_{h}^{(1)}\), \(w(t)=e^{i\omega ^{1/ \nu }t}\) in (9) and using (3), we get

Taking \(u(t)=t_{h}^{(2)}\), \(w(t)=e^{i\omega ^{1/\nu }t}\) in (9) and using (3), we get

which can be expressed as

Now (13) follows by continuing the above process and then replacing i by −i. □

Theorem 2.9

Let \(t\in (-\infty , \infty )\) and \(h>0\). If \(e^{\pm i\omega ^{1/\nu }h} \neq 1\), then we have

Proof

The proof follows from the second term of (3) and (13). □

Theorem 2.10

Let \(t\in (-\infty , \infty )\) and \(h>0\). If \(a^{h}e^{\pm i\omega ^{1/ \nu }h}\neq 1\), then

Proof

Since

the proof follows by taking \(\Delta _{h}^{-1}\) on both sides. □

3 1D fractional frequency Fourier transform and its properties

In this section, we define and obtain the properties of one dimensional fractional frequency Fourier transform and present the transforms of certain functions like trigonometric, hyperbolic, polynomials, etc. We also obtain some properties of Fourier transforms.

Definition 3.1

The fractional frequency Fourier transform (FFFT) of \(u(t)\) is defined as follows:

and the inverse generalized discrete Fourier transform of \(U(s)\) is given by

Similarly, the fractional frequency Fourier sine and cosine transforms of \(u(t)\) are defined as follows:

The inverse of Fourier sine and cosine transforms of the above are respectively given by

Let \(c_{1}\) and \(c_{2}\) be constants. From Definition 3.1, we can obtain the following linearity, change of scale, and shifting properties of fractional frequency Fourier transform.

Property 3.2

If \(F_{h,\nu }(u(t))=U(\omega )\) and \(F_{h,\nu }(v(t))=V(\omega )\), then

Example 3.3

Take \(u(t)=t_{h}^{(3)}\) for \(-4< t<4\). Then from (13) we get

For particular values of \(\nu =0.5\), \(\omega =3\), and \(h=1\), we provide MATLAB coding for verification as follows: \(U(\omega ) = \operatorname{symsum} ((4-r)\times (3-r)\times (2-r)\times \exp (-i\times 3^{(1/0.5)} \times (4-r) ), r,1,8 ) = (24\times (\exp (-i\times 3^{(1/0.5)}\times 4 ) ) )/ ( (\exp (-i \times 3^{(1/0.5)} )-1 ) ) - (36\times (\exp (-i\times 3^{(1/0.5)}\times 5 ) ) )/ ( (\exp (-i \times 3^{(1/0.5)} )-1 )^{2} ) + (24\times (\exp (-i\times 3^{(1/0.5)}\times 6 ) ) )/ ( (\exp (-i\times 3^{(1/0.5)} )-1 )^{3} ) - (6\times (\exp (-i\times 3^{(1/0.5)} \times 7 ) ) )/ ( (\exp (-i\times 3^{(1/0.5)} )-1 )^{4} ) + (120\times (\exp (i \times 3^{(1/0.5)}\times 4 ) ) )/ ( (\exp (-i\times 3^{(1/0.5)} )-1 ) ) + (60 \times (\exp (i\times 3^{(1/0.5)}\times 3 ) ) )/ ( (\exp (-i\times 3^{(1/0.5)} )-1 )^{2} ) + (24 \times (\exp (i\times 3^{(1/0.5)}\times 2 ) ) )/ ( (\exp (-i\times 3^{(1/0.5)} )-1 )^{3} ) + (6 \times (\exp (i\times 3^{(1/0.5)} ) ) )/ ( (\exp (-i\times 3^{(1/0.5)} )-1 )^{4} )\).

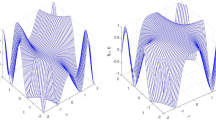

The outcomes are generated by MATLAB as diagrams. Figure 1 is the input function (signal) as polynomial factorial for the time factor t. Figure 2 is the fractional frequency Fourier transform in the frequency domain ω for the particular values of \(\omega =3\) and \(\nu =0.5\) which are generated. This shows that the signal runs smoothly in both real and imaginary parts of the frequency domain. One can generate functions easily by varying ω and ν to analyze the signal processing in the axis.

4 Convolution product and fractional Fourier transform

In this section, we establish discrete convolution theorem and fractional Fourier transform based on generalized operator \(\Delta _{h}\). When \(h\rightarrow 0\), we get convolution theorem and Fourier transform.

Definition 4.1

Let u and v be two bounded functions on \((-\infty ,+\infty )\). Then the convolution of u and v is defined as

It is easy to see that \(u\circ v=v\circ u\).

Remark 4.2

When both u and v vanish on the negative real axis, \(v(x-t)=0\) if \(t>x\) and (27) becomes

Theorem 4.3

Let \(\mathbb{R}=(-\infty ,\infty )\). Assume that \(u, v\in L( \mathbb{R})\) = set of all Lebesgue integrable functions on \(\mathbb{R}\) and that either u or v is bounded on \(\mathbb{R}\). Then the convolution

exists for every x in \(\mathbb{R}\) and the function w so defined is bounded on \(\mathbb{R}\). If, in addition, the bounded function u or v is continuous on \(\mathbb{R}\), then w is also continuous on \(\mathbb{R}\) and \(w\in L(\mathbb{R})\).

Proof

Since \(u\circ v=v\circ u\), it suffices to consider the case in which v is bounded. Suppose \(\vert v \vert \leq M\). Then

Since \(u(t)v(x-t)\) is a measurable function of t on \(\mathbb{R}\), from (27) and (30), we get \(\Delta _{\ell }^{-1} \vert u(t) v(x-t) \vert | _{-\infty }^{\infty }\leq M\Delta _{h}^{-1} \vert u(t) \vert | _{- \infty }^{\infty }\Rightarrow \vert w(x) \vert \leq M \Delta _{h}^{-1} \vert u(t) \vert | _{-\infty }^{\infty }\), which tells that w is bounded on \(\mathbb{R}\). Also, if v is continuous on \(\mathbb{R}\), then w is continuous on \(\mathbb{R}\). Now, for every compact interval \([a,b ]\), we have

where \(y=x-t\). □

Since w is bounded and continuous on \(\mathbb{R}\), \(w\in L(\mathbb{R})\).

5 Discrete convolution theorem for discrete Fourier transform

The following theorem illustrates the relation between convolution and Fourier transform.

Theorem 5.1

Assume that \(u,v\in L(\mathbb{R})\) and that at least one of u or v is continuous and bounded on \(\mathbb{R}\). Let h denote the convolution and \(w=u\circ v\). Then, for every real ν, we have

Proof

Assume that v is continuous and bounded on \(\mathbb{R}\). Let \({a_{n}}\) and \({b_{n}}\) be two increasing sequences of positive real numbers such that \({a_{n}}\rightarrow +\infty \) and \({b_{n}}\rightarrow +\infty \). Define a sequence of functions \({u_{n}}\) on \(\mathbb{R}\) as \({u_{n}}(t)=\Delta ^{-1}_{h}e^{-ix \nu }v(x-t)| _{-a_{n}}^{b_{n}}\).

Since \(\vert \Delta ^{-1}_{h}e^{-ix\nu }v(x-t) \vert | _{-a_{n}}^{b_{n}}\leq \vert v \vert _{-\infty }^{\infty }\) for all compact intervals \([a,b]\). Now, for translation \(y=x-t\), we get

By Lebesgue dominated convergence theorem,

But from (32) and (27), \(\lim_{n\rightarrow \infty }\Delta ^{-1}_{h}u(t)u_{n}(t)| _{- \infty }^{\infty }=\Delta ^{-1}_{h}e^{-ix\nu }w(x)| _{- \infty }^{\infty }\), which completes the proof. The discrete integral on the left also exists as an improper Riemann integral is continuous and bounded on \(\mathbb{R}\) and \(\Delta ^{-1}_{h} \vert w(x)e^{-ix \nu } \vert \leq \Delta ^{-1}_{h}w| _{-\infty }^{\infty }\) for every interval \([a,b]\). □

The following example provides the numerical verification of convolution and the solutions are analyzed by graphs.

Example 5.2

Consider the following functions:

Now from (27) we get \((u\circ v)(t) = \Delta _{h}^{-1}a^{t}e ^{-i\omega ^{1/\nu }t}| _{t=-2}^{2}\). Then, using (15) gives \((u\circ v)(t)=\frac{ha^{t}e^{\pm i\omega ^{1/\nu }t}}{(a^{h}e^{ \pm i\omega ^{1/\nu }h}-1)}| _{-2}^{2}\). By (6), we get

which is verified for the particular values \(h=3\), \(a=5\), \(\omega =0.3\), and \(\nu =0.2\) by MATLAB coding given below: \(\operatorname{symsum}(3\times 5^{(2-3 \times r)}\times \exp (-i\times (0.3)^{(1/0.2)}\times (2-r\times 3)),r,1,4)=75 \times \exp (-i\times (0.3)^{(1/0.2)}\times 2)/(125\times \exp (-i\times (0.3)^{(1/0.2)}\times 3)-1)-3 \times \exp (-i\times (0.3)^{(1/0.2)} \times -2)/(25\times (125\times \exp (-i\times (0.3)^{(1/0.2)}\times 3)-1))\).

6 Conclusion

In this work, we proved some properties and results with frequency fractional factor \(\omega ^{1/\nu }\) using the inverse difference operator. We defined one dimensional fractional frequency Fourier transform and its convolution. The biggest advantage of our findings is that, when \(h\rightarrow 0\) and \(\nu =1\), the one dimensional fractional frequency Fourier transform becomes the Fourier transform which exists in the literature. We believe that the new extension and definitions will be valuable for researchers to develop the models in Fourier transform. When the Fourier transform does not exist for any function (signal), we can apply one dimensional fractional Fourier transform using (5) and (16) and get several applications in the field of digital signal processing.

References

Abdeljawad, T.: Discrete Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2013, 406910 (2013)

Abdeljawad, T.: Adv. Differ. Equ. 2013, 36 (2013)

Abdeljawad, T., Atici, F.: Abstr. Appl. Anal. 2012, 406757 (2012)

Abdeljawad, T., Baleanu, D.: J. Nonlinear Sci. Appl. 10, 1098 (2017)

Abdeljawad, T., Baleanu, D.: Adv. Differ. Equ. 2017, 78 (2017)

Abdeljawad, T., Baleanu, D.: Chaos Solitons Fractals 102, 106 (2017)

Abdeljawad, T., Jarad, F., Baleanu, D.: Adv. Differ. Equ. 2012, 72 (2012)

Agarwal, P., Al-Mdallal, Q., Cho, Y.J., Jain, S.: Fractional differential equations for the generalized Mittag-Leffler function. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2018, 58 (2018)

Agarwal, P., El-Sayed, A.A.: Non-standard finite difference and Chebyshev collocation methods for solving fractional diffusion equation. Phys. A, Stat. Mech. Appl. 500, 40–49 (2018)

Agarwal, R.P.: Difference Equations and Inequalities. Dekker, New York (2000)

Akansu, A.N., Poluri, R.: Walsh-like nonlinear phase orthogonal codes for direct sequences CDMA communications. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 55, 3800–3806 (2007)

Atici, F.M., Eloe, P.W.: Fractional q-calculus on a time scale. J. Nonlinear Math. Phys. 14(3), 333–344 (2007)

Atici, F.M., Eloe, P.W.: A transform method in discrete fractional calculus. Int. J. Difference Equ. 2(2), 165–176 (2007)

Atıcı, F.M., Eloe, P.W.: Electron. J. Qual. Theory Differ. Equ., Spec. Ed. I 2009, 1 (2009)

Atici, F.M., Eloe, P.W.: Two-point boundary value problems for finite fractional difference equations. J. Differ. Equ. Appl. (2011). https://doi.org/10.1080/10236190903029241

Baltaeva, U., Agarwal, P.: Boundary value problems for the third order loaded equation with non characteristic type change boundaries. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 41(9), 3307–3315 (2018)

Bastos, N.R.O., Ferreira, R.A.C., Torres, D.F.M.: Discrete-time fractional variational problems. Signal Process. 91(3), 513–524 (2011)

Britanak, V., Rao, K.R.: The fast generalized discrete Fourier transforms: a unified approach to the discrete sinusoidal transforms computation. Signal Process. 79, 135–150 (1999)

Choi, J., Agarwal, P.: Certain fractional integral inequalities involving hypergeometric operators. East Asian Math. J. 30(3), 283–291 (2014)

Goodrich, C., Peterson, A.: Discrete Fractional Calculus. Springer, New York (2015)

Goodrich, C.S.: Solutions to a discrete right-focal boundary value problem. Int. J. Difference Equ. 5, 195–216 (2010)

Goodrich, C.S.: Continuity of solutions to discrete fractional initial value problems. Comput. Math. Appl. 59, 3489–3499 (2010)

Goodrich, C.S.: Some new existence results for fractional difference equations. Int. J. Dyn. Syst. Differ. Equ. 3, 145–162 (2011)

Holm, M.: Sum and difference compositions in discrete fractional calculus. CUBO 13(3), 153–184 (2011)

Jain, S., Agarwal, P., Kilicman, A.: Pathway fractional integral operator associated with 3m-parametric Mittag-Leffler functions. Int. J. Appl. Comput. Math. 4(5), 115 (2018)

Mehrez, K., Agarwal, P.: New Hermite Hadamard type integral inequalities for convex functions and their applications. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 350, 274–285 (2018)

Miller, K.S., Ross, B.: An Introduction to the Fractional Calculus and Fractional Differential Equations. Wiley, New York (1993)

Ni, L., Da, X., Hu, H., Liang, Y., Xu, R.: PHY-aided secure communication via weighted fractional Fourier transform. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2018, Article ID 7963451 (2018)

Oldham, K., Spanier, J.: The Fractional Calculus: Theory and Applications of Differentiation and Integration to Arbitrary Order. Dover, Mineola (2002)

Pedersen, A.F., Simons, H., Detlefs, C., Poulsen, H.F.: The fractional Fourier transform as a simulation tool for lens-based X-ray microscopy. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 25, 717–728 (2018)

Podlubny, I.: Fractional Differential Equations. Academic Press, New York (1999)

Sitho, S., Ntouyas, S.K., Agarwal, P., Tariboon, J.: Noninstantaneous impulsive inequalities via conformable fractional calculus. J. Inequal. Appl. 2018, 261 (2018)

Smith, J.O.: Mathematics of the Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT). February, 2010 (date accessed), online book

Smith, S.W.: The Scientist and Engineer’s Guide to Digital Signal Processing, 2nd edn. California Technical Publishing, San Diego (1999)

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to express their gratitude to the editors and the reviewers for their helpful comments.

Availability of data and materials

Please contact author for data requests.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed equally and significantly in writing this paper. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

All the authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Baleanu, D., Alqurashi, M., Murugesan, M. et al. One dimensional fractional frequency Fourier transform by inverse difference operator. Adv Differ Equ 2019, 212 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-019-2071-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-019-2071-y