Abstract

In this paper, a predator–prey model with ratio-dependent and impulsive state feedback control is constructed, where the pest growth rate is related to an Allee effect. Firstly, the existence condition of the homoclinic cycle is obtained by analyzing the control parameter q. The existence, uniqueness and asymptotic stability of the periodic orbit are discussed by using the geometric theory of the differential equations, the method of successor functions and analog of the Poincaré criterion. Secondly, we formulate a control optimization with a minimal total cost in pest management, and we obtain an optimal economic threshold. Finally, we verify the main results by numerical simulation.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Differential equations can be applied extensively in many fields, including economic development, environmental protection, population ecology, infectious diseases and pharmacokinetics, and the cultivation of micro-organisms [1,2,3,4,5,6]. In [3], Cui et al. proposed the fractional differential equations and analyzed the uniqueness of solution for boundary value problems. Many researchers have obtained very good achievements in the field of stochastic differential equations [7,8,9,10,11,12].

In recent decades, many researchers have found that the occurrence of some biological phenomena and the optimal control of some life phenomena were not continuous processes, but the transient behavior of an impulse, so we should use impulsive differential equations to describe these phenomena. The theory of impulsive differential equations is proposed on the basis of continuous differential equation theory, which is difficult but valuable. It is widely applied in the harvest description [13,14,15,16], ecological resources [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26], pest control [27,28,29,30,31] and epidemiologic control [32,33,34,35,36]. Many scholars investigated state-dependent pulse differential equations in predator–prey model to simulate the pest management including the periodic release of natural enemies [37,38,39] and the periodic release of natural enemies combined with periodic spraying of pesticides [40,41,42,43,44,45,46]. On the other hand, the bifurcation theory has been widely applied in the continuous dynamic system [47,48,49]. However, its application in impulsive dynamical system was little.

In [50], Zhang et al. proposed a predator–prey model with multi-state pulse feedback control as follows:

where \(h_{1}\) and \(h_{2}\) are the biological control level (i.e. the threshold with slight damage to the crops) and the chemical control level (i.e. pest economic injury threshold), respectively. \(y_{\mathrm{ML}}\) represents the predator maintainable level at \(x=h_{1}\). It is interesting and practically significant to involve chemical and biological controls at different economic thresholds, but there is a key problem to be identified in the model. Biological control can be adopted at \(x=h_{1}\) and \(y< y_{\mathrm{ML}}\), but for a higher pest density \(x=h\), where \(h_{1}< h< h_{2}\), there no control strategy is adopted, therefore the model is not flawless.

Based on above the factors, we propose a ratio-dependent predator–prey system with an integrated control strategy as follows:

where \(\Delta x_{1}(t_{1})=x_{1}(t_{1}^{+})-x_{1}(t_{1})\), \(\Delta y _{1}(t_{1})=y_{1}(t_{1}^{+})-y_{1}(t_{1})\), \(x_{1}\) and \(y_{1}\) represent the density of the prey and predator at time \(t_{1}\), respectively. r denotes the intrinsic rate growth of pests. \(h'\in [h_{1}',h_{2}']\) represents the threshold of pests, where \(h_{1}'\) and \(h_{2}'\) are biological control level and chemical control level, respectively. \(K>0\) represents the environment carrying capacity of pests. m denotes the attack rate of predator. b denotes the handling time of a single pest by natural enemies. c is the conversion ratio of consumed pests into viable natural enemy offspring. \(\beta _{1}\) is the death rate of predator. The parameter \(\alpha _{1}\) represents the survival threshold of the pest population for the Allee effect. \(0<\alpha _{1}<K\) is the survival threshold of the pest population for the strong Allee effect, \(-K<\alpha _{1}<0\) is the survival threshold of the pest population for the weak Allee effect. In this paper, only \(0<\alpha _{1}<K\) is taken into consideration. For reducing the parameters, we nondimensionalize system (2) with the following scaling:

then the following form can be obtained:

where \(\alpha =\frac{\alpha _{1}}{K}\), \(\lambda =\frac{1}{rbK}\), \(\lambda _{1}=\frac{cm}{rK}\), \(\beta =\frac{\beta _{1}}{rK}\), \(\tau =\frac{mb\tau _{1}}{K}\), \(h=\frac{1}{K}h'\), \(h_{1}=\frac{1}{K}h _{1}'\), \(h_{2}=\frac{1}{K}h_{2}'\), and they are all positive constants. We can refer to [51, 52] for the analysis of the term \(\frac{xy}{x+y}\) at \(O(0,0)\). The parameters \(p(x)\), \(q(x)\), \(\tau (x)\) are continuous functions defined on \([h_{1},h_{2}]\), where \(\tau (h_{1})=\tau _{\max }\), \(\tau (h_{2})=\tau _{\min }\), \(p(h_{1})=0\), \(p(h_{2})=p_{\max }\), \(q(h_{1})=0\), \(q(h_{2})=q_{\max }\). In this paper, the functions p, q, τ are defined in a linear form [53], i.e.

The organizational structure of this article is as follows. In Sect. 2, the existence of homocilinic cycle and existence, uniqueness and asymptotic stability of the periodic orbit of system (3) are proved. Furthermore, the optimization problem is formulated to reduce the total cost of pest control (i.e. the predator and the spraying agent). In Sect. 3, the numerical simulation of the concrete model is gradually carried out to verify the theoretical results. The final conclusion is drawn in Sect. 4.

2 Dynamical analysis of system (3)

2.1 Equilibria

Without impulse effect, system (3) becomes the following:

Theorem 2.1

([51])

System (5) has five equilibria: origin \(O(0,0)\), two boundary equilibria: \(N_{1}(\alpha ,0)\) and \(N_{2}(1,0)\) and two positive equilibria: \(E_{1}(x_{1},y_{1})\) and \(E_{2}(x_{2},y _{2})\), where \(x_{1}=\frac{1+\alpha -\sqrt{(1-\alpha )^{2}-4\lambda (1-\frac{\beta }{\lambda _{1}})}}{2}\), \(y_{1}=\frac{(\lambda _{1}- \beta )x_{1}}{\beta }\), \(x_{2}=\frac{1+\alpha +\sqrt{(1-\alpha )^{2}-4 \lambda (1-\frac{\beta }{\lambda _{1}})}}{2}\), \(y_{2}=\frac{(\lambda _{1}-\beta )x_{2}}{\beta }\).

If \((H_{1})\) \(x(t_{0})=x_{0}<\alpha \), \(y(t_{0})=y_{0}>0\) holds, then the equilibrium \(O(0,0)\) of system (5) is stable.

If \((H_{2})\) \(\lambda _{1}>\beta \) holds, then the equilibrium \(N_{1}\) is an unstable node and \(N_{2}\) is a saddle point.

If \((H_{3})\) \(\lambda _{1}<\beta \) holds, then the equilibrium \(N_{1}\) is a saddle point and \(N_{2}\) is a stable node.

If \((H_{4})\) \(\lambda _{1}>\beta >\frac{\alpha _{1}}{4\lambda }[4\lambda -(1-\alpha )^{2}]>0\) holds, then equilibria \(E_{1}\) and \(E_{2}\) are positive equilibria.

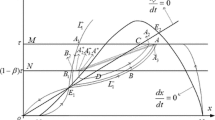

If \((H_{5})\) \(\operatorname{Tr}(J(E_{2}))=x_{2}(1+\alpha -2x_{2})+\frac{\beta ( \lambda -\lambda _{1})(\lambda _{1}-\beta )}{\lambda _{1}^{2}}<0\) holds, then point \(E_{1}\) is a saddle point and point \(E_{2}\) is a locally asymptotically stable node or focus (see Fig. 1).

Phase diagram of system (5) with \(a=0.1\), \(\lambda =0.5\), \(\beta =0.55\), \(\lambda _{1}=0.8\)

2.2 Existence of the order one periodic orbit and homoclinic cycle of system (3)

By using the geometric theory of differential equations and the method of successor function, the existence of the order one periodic orbit and homoclinic cycle of system (3) is investigated in this section. For the actual biological significance, we always suppose that \(\max \{\frac{1+\alpha -\sqrt{(1-\alpha )^{2}-4\lambda (1-\frac{ \beta }{\lambda _{1}})}}{2},h_{1}\}<(1-p)h<h<\min \{\frac{1+\alpha +\sqrt{(1- \alpha )^{2}-4\lambda (1-\frac{\beta }{\lambda _{1}})}}{2},h_{2}\}\) and conditions \((H_{4})\), \((H_{5})\) hold in the paper.

Set \(M=\{(x,y)|x=h,0\leq y\leq y_{h}\}\) is called an impulsive set and set \(N=\{(x,y)|x=(1-p)h,\tau \leq y\leq (1-q)y_{h}+\tau \}\) is called a phase set. For convenience, for any point L, let \(x_{L}\) and \(y_{L}\) denote its abscissa and ordinate, respectively. I is a continuous mapping which satisfies \(I(M)=N\) and which is called an impulsive function. If \(L(h,y_{L})\in M\), then the impulse function transfers the point L into \(L^{+}\). We denote function \(F(J)=J^{-}\) as the trajectory starting from the point \(J\in N\) hits the impulse set M at the point \(J^{-}\). In this paper, the tendency of trajectory is assumed to start from phase set. The unstable manifold and stable manifold of \(E_{1}\) are denoted as \(T_{1}^{-}(t,E_{1})\) and \(T_{1}^{+}(t,E_{1})\), respectively. At time t, \(T_{1}^{-}(t,E_{1})\) intersects phase set N at point \(A_{1}\) and impulsive set M at point \(B_{1}\). At time t, \(T_{1}^{+}(t,E_{1})\) intersects phase set N at point \(A_{2}\) and impulsive set M at point \(B_{2}\). Isocline \(\varGamma _{1}\): \(\frac{dy}{dt}=0\) intersects phase set N at point A and impulsive set M at point B, where \(y_{A}=\frac{h(1-p)( \lambda _{1}-\beta )}{\beta }\) and \(y_{B}=\frac{(\lambda _{1}-\beta )h}{ \beta }\). The function \(\varphi (y,q)=(1-q)y+\tau \) is monotonically decreasing about q, and monotonically increasing about y, thus there must exist a value \(q_{*}\in (0,1)\) such that point B jumps to A after the impulse effect, i.e. \(\varphi (y_{B},q_{*})=(1-q_{*})y _{B}+\tau =y_{A}\), we have \(q_{*}=p+\frac{\beta \tau }{(\lambda _{1}- \beta )h}\), for convenience, we set \(\delta =p+\frac{\beta \tau }{( \lambda _{1}-\beta )h}\). For any \(q\in (0,1)\), the existence of order one periodic orbit of system (3) is to be proved in the cases of \(0< q\leq \delta \) and \(\delta < q<1\), respectively (see Fig. 2).

Illustration of system (5)

Case I \(0< q\leq \delta \).

Theorem 2.2

-

(a)

If conditions \((H_{4})(H_{5})\) and \(q=\delta \) hold, then system (3) admits a unique order one periodic orbit.

-

(b)

If conditions \((H_{4})(H_{5})\) and \(0< q^{*}< q< q^{0}<\delta <1\) hold, then system (3) admits a unique order one periodic orbit.

Proof

The trajectory starting from the point \(A\in N\) hits the point \(B\in M\), then point \(B\in M\) jumps to point \(B^{+}\) after impulsive effect.

(a) Firstly, we prove the existence of the order one periodic orbit of system (3) in the case of \(q=\delta \). In this case, \(B^{+}\) coincides with point A, that is, \(\widehat{AB}\) and \(\overline{BA}\) constitute the order one periodic orbit.

(b) In this case, \(B^{+}\) is above A. According to the impulsive equations of system (3), there surely has a value \(q^{*} \in (0,\delta )\) satisfying \(\varphi (y_{B_{1}},q^{*})=(1-q^{*})y_{B _{1}}+\tau =y_{A_{2}}\), that is, point \(B_{1}\) jumps to point \(A_{2}\) after impulse effect, also, there surely has a value \(q^{0}\in (q^{*},\delta )\) satisfying \(\varphi (y_{B_{1}},q^{0})=(1-q ^{0})y_{B_{1}}+\tau =y_{A}\). For any \(q\in (q^{*},q^{0})\), point \(B_{1}\) jumps to point \(B_{1}^{+}\) after impulsive effect, we have \((1-q^{0})y_{B_{1}}+\tau =y_{A}<(1-q)y_{B_{1}}+\tau =y_{B_{1}^{+}}<(1-q ^{*})y_{B_{1}}+\tau =y_{A_{2}}\), that is, \(y_{A}< y_{B_{1}^{+}}< y_{A _{2}}\). There must exist a trajectory going through point \(B_{1}^{+}\) and intersecting the line \(x=h\) at point \(C_{1}\), and \(I(C_{1})=C_{1} ^{+}\). In view of the disjointness of any two trajectories and the vector field of system (3), we have \(y_{B_{1}}< y_{C_{1}}< y _{B}\), \((1-q)y_{B_{1}}+\tau =y_{B_{1}^{+}}<(1-q)y_{C_{1}}+\tau =y_{C _{1}^{+}}\), that is, \(y_{C_{1}^{+}}>y_{B_{1}^{+}}\). Thus the successor function [54, Definition 3.3] of \(B_{1}^{+}\): \(g(B_{1} ^{+})=y_{C_{1}^{+}}-y_{B_{1}^{+}}>0\).

A point \(C((1-p)h, y_{A_{2}}-\varepsilon )\) is selected in set N, where \(\varepsilon >0\) is small enough, then point C is fully close to point \(A_{2}\). Set \(F(C)=C_{2}\in M \), we have \(y_{C_{2}}>y_{B_{1}}\) due to continuous dependence of the solution on initial value and time, and \(C_{2}\) is close enough to point \(B_{1}\). Thus we have \(y_{C_{2} ^{+}}>y_{B_{1}^{+}}\), and point \(C_{2}^{+}\) is close enough to point \(B_{1}^{+}\), then we have \(y_{C_{2}^{+}}< y_{C}\), that is, \(g(C)=y_{C _{2}^{+}}-y_{C}<0\). According to [54, Lemma 3.2, 3.3], there has a point \(P\in (B_{1}^{+},C)\) such that \(g(P)=0\), i.e. system (3) admits the order one periodic orbit, whose initial point is between point \(B_{1}^{+}\) and point C in the set N (see Fig. 3(a)).

Next, we prove the uniqueness of the order one periodic orbit of system (3). We arbitrarily select two points K and Q in the \(\overline{AA_{2}}\), where \(y_{A}< y_{K}< y_{Q}< y_{A_{2}}\). Set \(F(K)=K_{1}\in M\), \(F(Q)=Q_{1}\in M\), then we have \(y_{Q_{1}}< y_{K_{1}}\), and \(K_{1}\) and \(Q_{1}\) are, respectively, mapped to \(K_{1}^{+}\in N\) and \(Q_{1}^{+}\in N\) after the impulse effect, then the successor functions of K, Q satisfy

Thus the successor function is monotonically increasing in the \(\overline{AA_{2}}\), then there is only one point \(P\in (A,A_{2})\) such that \(g(P)=0\), i.e. system (3) has only an order one periodic orbit when q satisfies \(0< q<\delta \) (see Fig. 3(b)). This completes the proof. □

Theorem 2.3

If conditions \((H_{4})\) and \((H_{5})\) and \(q=q^{*}\) hold, then system (3) admits an order one homoclinic cycle; if \(q\in (0,q^{*})\), system (3) does not admit an order one periodic orbit and the pests and natural enemy population will become extinct.

Proof

When \(q=q^{*}\), we have \(\varphi (y_{B_{1}}, q_{*})=(1-q^{*})y_{B_{1}}+ \tau =y_{A_{2}}\), then the closed curve \(\overline{B_{1}A_{2}}\cup \widehat{A_{2}E_{1}}\cup \widehat{E_{1}B_{1}}\) forms a cycle which passes through the saddle \(E_{1}\). Thus system (3) admits an order one homoclinic cycle (see Fig. 4).

The order one homoclinic cycle of system (3) in case I

When \(q\in (0,q^{*})\), we have \((1-q)y_{B_{1}}+\tau =y_{B_{1}^{+}}>(1-q ^{*})y_{B_{1}}+\tau =y_{A_{2}}\) and the trajectory of system (3) starting from \(B_{1}^{+}\) will tend to origin when \(t\rightarrow +\infty \), and it has no impulse effect. Thus system (3) has no order one periodic orbit and the pest and natural enemy population will become extinct. This completes the proof. □

Case II \(\delta < q<1\).

Theorem 2.4

If the conditions \((H_{4})(H_{5})\) and \(\delta < q<1\) hold, then the system (3) admits the order one periodic orbit.

Proof

In this case, we know that \(B^{+}\) is below A. Set \(F(B^{+})=S_{1} \in M\), according to the property of orbit of system (3), we know \(y_{B}>y_{S_{1}}\), thus we have \(y_{B^{+}}>y_{S_{1}^{+}}\), then the successor function of point \(B^{+}\) is \(g(B^{+})=y_{S_{1}^{+}}-y_{B ^{+}}<0\). A point \(H((1-p)h,\varepsilon )\in N\) is selected, where \(\varepsilon <\tau \), and set \(F(H)=H_{1}\in M\), after impulsive effect, point \(H_{1}\) jumps to \(H_{1}^{+}\), then \(y_{H_{1}^{+}}=(1-q)y_{H_{1}}+ \tau >\varepsilon \), that is, \(y_{H_{1}^{+}}>y_{H}\), thus we have \(g(H)=y_{H_{1}^{+}}-y_{H}>0\). By [54, Lemma 3.2, 3.3], there exists a point \(P\in (H,B^{+})\) satisfying \(g(P)=0\), that is, system (3) admits the order one periodic orbit, whose initial point is between H and \(B^{+}\) in the set N. This completes the proof (see Fig. 5).

The existence of the order one periodic orbit of system (3) in case II

□

2.3 Stability of the order one periodic orbit of system (3)

Next, we study the stability of the order one periodic orbit of system (3).

Theorem 2.5

If conditions \((H_{4})\), \((H_{5})\), and \((1-\alpha )+\frac{\lambda h}{ \alpha }-\frac{\lambda _{1}\alpha y_{1}}{(1+h)^{2}}<0\) and \(\vert \chi \vert <1\) hold, then the order one periodic orbit of system (3) is orbitally asymptotically stable, where

Proof

Let \(x=\xi (t)\), \(y=\eta (t)\) be a T-periodic orbit of system (3) and \(\xi _{1}=\xi (T)=h\), \(\eta _{1}=\xi (T)\), \(\xi _{0}= \xi (0)\), \(\eta _{0}=\eta (0)\), \(\xi _{1}^{+}=\xi (T^{+})\), \(\eta _{1}^{+}= \eta (T^{+})\), then we have

Let \(P(x,y)=x(x-\alpha )(1-x)-\frac{\lambda xy}{x+y}\), \(Q(x,y)=\frac{ \lambda _{1}xy}{x+y}-\beta y\), \(\varPhi (x,y)=-px\), \(\varPsi (x,y)=-qy+ \tau \), \(\varUpsilon (x,y)=x-h\).

Then

and

Furthermore,

For any point \((x,y)\in \varTheta \), \(\alpha < x<1\) and \(y_{1}< y< h\), we have \((1-\alpha )+\frac{\lambda h}{\alpha }- \frac{\lambda _{1}\alpha y_{1}}{(1+h)^{2}}<0\), so we can get

and due to \(\vert \chi \vert <1\), we have

Therefore \(\vert \mu _{2} \vert <1\). According to the analog of the Poincaré criterion [55, Theorem 2.3], we know that the order one periodic orbit of system (3) is orbitally asymptotically stable. This completes the proof. □

2.4 Determination of optimal pest economic threshold

In order to determine the optimum release amount of natural enemies and the optimal frequency of spraying chemical pesticide, we formulate the following optimization problem and find the optimal economic threshold.

Let \(l_{1}\) represent the unit cost of the biological control, \(l_{2}\) the unit cost of the chemical control. Our final purpose is to minimize the expenses of per unit period. We denote by F the total expenses in a period of system (3), which is a function of the chemical control strength \(p(h)\) and release amount of natural enemies \(\tau (h)\). Then we have \(F(h)=l_{1}\tau (h)+l_{2}p(h)\). Thus we formulate the following optimization model:

Solving the objective function yields the optimum economic threshold \(h^{*}\), which results in the optimum release amount of the predator \(\tau ^{*}=\tau (h^{*})\), the optimal chemical control strength \(p^{*}=p(h^{*})\) and the optimal control period of chemical control \(T^{*}=T(\tau ^{*},p^{*})\). However, it is important to be noted that the optimal economic threshold \(h^{*}\) is dependent on the ratio of \(\omega =\frac{l_{2}}{l_{1}}\).

3 Simulations and optimization

In order to verify the theoretical results obtained in this paper, a specific example is presented in this section. Let \(\alpha =0.1\), \(\lambda =0.5\), \(\lambda _{1}=0.8\), \(\beta =0.55\), \(h_{1}=0.35\), \(h_{2}=0.76\), \(p _{\max }=0.3\), \(\tau _{\max }=0.1\), \(\tau _{\min }=0.01\), \(q_{\max }=0.8\). By a simple calculation, the saddle point and locally asymptotically stable point are \(E_{1}(0.3349,0.1522)\) and \(E_{0}(0.7651,0.3478)\), respectively. We carry out simulations by changing the main parameter h and fixing all other parameters. The control parameters p, q, τ are calculated by (4).

3.1 Numerical simulations

Taking parameters α, λ, β, \(\lambda _{1}\) into system (5), we can obtain

Furthermore, Fig. 6(a) shows the phase portrait of \(x(t)\) and \(y(t)\), Fig. 6(b) shows time series of \(x(t)\), Fig. 6(c) shows time series of \(y(t)\). Let \(p=0.27\), \(h=0.61\), \(\tau =0.18\), we shall get \(\delta =p+\frac{\beta \tau }{(\lambda _{1}-\beta )h}=0.27+\frac{0.55 \times 0.18}{(0.8-0.55)\times 0.61}=0.92\). Let \(q=0.01\) we shall get Fig. 7. Figures 7(a), 7(b) and 7(c) show that system (3) does not have order one periodic orbit and the pest and natural enemy population become extinct when \(0< q< q^{*}\). Let \(q=0.6\), \(q=0.7\) and \(q=0.8\) and we shall get a unique order one periodic solution and it is asymptotically stable (see Fig. 8). Furthermore, according to Fig. 8, we see that, as the parameter q increases, the period T becomes smaller. Figure 9 shows that system (3) admits the order one periodic orbit when \(q>\delta \). According to Fig. 9, we see that, as the parameter q increases, the period T becomes smaller.

3.2 Optimum pest control level

The impulse period T of the order one periodic orbit varies with the economic threshold h, as is shown in Fig. 10. And Fig. 11 shows the variation of cost per unit time \(F/T\) and the period T with the pest control level h. Assume \(l_{1}=10{,}000\), \(l_{2}=100\), we shall get \(\omega =\frac{l_{2}}{l_{1}}=1/100\).

The optimal pest threshold is \(h^{*}=0.46\), the optimal chemical control strength is \(p^{*}=0.0878\), the optimal release amount of the natural enemies is \(\tau ^{*}=0.0737\). It is important to note that the optimum economic threshold h is dependent on ω, that is, the larger ω is, the lower h is, as is illustrated in Fig. 12.

4 Conclusion

In this paper, a predator–prey model with ratio-dependent and impulsive state feedback control is proposed. We take control measures that combine biological control and chemical control. The aim of this study is to get optimum pest control level and minimize the cost of pest control.

Based on the above analysis, both the predator and the prey are extinct when \(0< q< q^{*}\), that is, the order one periodic orbit does not exist when \(0< q< q^{*}\), system (3) admits an order one homoclinic cycle for \(q=q^{*}\); we obtain a unique and stable order one periodic orbit according to the geometric theory of the differential equations and the method of subsequence functions in the case of \(q^{*}< q<\delta \); and system (3) admits the order one periodic orbit in the case of \(\delta < q<1\).

In order to reduce the total cost of pest management, an optimization problem is formulated, and the optimal economic threshold and the minimum control cost are obtained. Finally, numerical simulation is carried out to verify the theoretical results.

References

Bai, Z., Zhang, S., Sun, S., Yin, C.: Monotone iterative method for fractional differential equations. Electron. J. Differ. Equ. 2016, 6 (2016)

Liu, F.: Continuity and approximate differentiability of multisublinear fractional maximal functions. Math. Inequal. Appl. 21(1), 25–40 (2018)

Cui, Y.: Uniqueness of solution for boundary value problems for fractional differential equations. Appl. Math. Lett. 51, 48–54 (2016)

Liu, F., Xue, Q., Yabuta, K.: Rough maximal singular integral and maximal operators supported by subvarieties on Triebel–Lizorkin spaces. Nonlinear Anal. 171, 41–72 (2018)

Lv, W., Wang, F.: Adaptive tracking control for a class of uncertain nonlinear systems with infinite number of actuator failures using neural networks. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2017(1), 374 (2017)

Zou, Y., Liu, L., Cui, Y.: The existence of solutions for four-point coupled boundary value problems of fractional differential equations at resonance. Abstr. Appl. Anal. 2014(13), 286 (2014)

Brauer, F., Soudack, A.C.: Stability regions in predator–prey systems with constant-rate prey harvesting. J. Math. Biol. 8(1), 55–71 (1979)

Yu, X., Yuan, S., Zhang, T.: Persistence and ergodicity of a stochastic single species model with Allee effect under regime switching. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 59, 359–374 (2018)

Liu, G., Wang, X., Meng, X.: Extinction and persistence in mean of a novel delay impulsive stochastic infected predator–prey system with jumps. Complexity 2017(3), 115 (2017)

Zhang, T., Zhang, T., Meng, X.: Stability analysis of a chemostat model with maintenance energy. Appl. Math. Lett. 68, 1–7 (2017)

Meng, X., Wang, L., Zhang, T.: Global dynamics analysis of a nonlinear impulsive stochastic chemostat system in a polluted environment. J. Appl. Anal. Comput. 6(3), 865–875 (2016)

Zhao, Q., Li, X.: A Bargmann system and the involutive solutions associated with a new 4-order lattice hierarchy. Anal. Math. Phys. 6(3), 237–254 (2016)

Wang, J., Cheng, H., Liu, H., Wang, Y.: Periodic solution and control optimization of a prey–predator model with two types of harvesting. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2018(1), 41 (2018)

Wei, C., Chen, L.: Periodic solution and heteroclinic bifurcation in a predator–prey system with Allee effect and impulsive harvesting. Nonlinear Dyn. 76(2), 1109–1117 (2014)

Martin, A., Ruan, S.: Predator–prey models with delay and prey harvesting. J. Math. Biol. 43(3), 247–267 (2001)

Huang, M., Liu, S., Song, X., Chen, L.: Periodic solutions and homoclinic bifurcation of a predator–prey system with two types of harvesting. Nonlinear Dyn. 73(1–2), 815–826 (2013)

Zhao, L., Chen, L., Zhang, Q.: The geometrical analysis of a predator–prey model with two state impulses. Math. Biosci. 238(2), 55–64 (2012)

Tang, S., Chen, L.: Global attractivity in a food-limited population model with impulsive effects. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 292(1), 211–221 (2004)

Zhang, M., Song, G., Chen, L.: A state feedback impulse model for computer worm control. Nonlinear Dyn. 85(3), 1–9 (2016)

Liu, H., Cheng, H.: Dynamic analysis of a prey–predator model with state-dependent control strategy and square root response function. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2018(1), 63 (2018)

Jiang, G., Lu, Q.: Impulsive state feedback control of a predator–prey model. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 200(1), 193–207 (2007)

Zhao, W., Li, J., Meng, X.: Dynamical analysis of SIR epidemic model with nonlinear pulse vaccination and lifelong immunity. Discrete Dyn. Nat. Soc., 2015, 848623 (2015)

Liu, X., Zhang, T., Meng, X., Zhang, T.: Turing-Hopf bifurcations in a predator–prey model with herd behavior, quadratic mortality and prey-taxis. Phys. A, Stat. Mech. Appl. 496, 446–460 (2018)

Qi, H., Liu, L., Meng, X.: Dynamics of a nonautonomous stochastic SIS epidemic model with double epidemic hypothesis. Complexity 2017(3), Article ID 4861391 (2017)

Li, Y., Cheng, H., Wang, Y.: A lycaon pictus impulsive state feedback control model with Allee effect and continuous time delay. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2018(1), 367 (2018)

Zhang, T., Liu, X., Meng, X., Zhang, T.: Spatio-temporal dynamics near the steady state of a planktonic system. Comput. Math. Appl. 75(12), 4490–4504 (2018)

Lenteren, J.C.: Integrated pest management in protected crops. Integr. Pest Manag. D 17(3), 270–275 (1995)

Tian, Y., Zhang, T., Sun, K.: Dynamics analysis of a pest management prey–predator model by means of interval state monitoring and control. Nonlinear Anal. Hybrid Syst. 23, 122–141 (2017)

Wang, J., Cheng, H., Meng, X., Pradeep, B.S.A.: Geometrical analysis and control optimization of a predator–prey model with multi state-dependent impulse. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2017(1), 252 (2017)

Pang, G., Chen, L.: Periodic solution of the system with impulsive state feedback control. Nonlinear Dyn. 78(1), 743–753 (2014)

Chen, L.: Pest control and geometric theory of semi-continuous dynamical system. J. Beihua Univ. (2011). doi:1009-4822(2011)01-0001-09

Meng, X., Wang, L., Zhang, T.: Global dynamics analysis of a nonlinear impulsive stochastic chemostat system in a polluted environment. J. Appl. Anal. Comput. 6(3), 865–875 (2016)

Miao, A., Wang, X., Zhang, T., Wang, W., Sampath Aruna Pradeep, B.: Dynamical analysis of a stochastic sis epidemic model with nonlinear incidence rate and double epidemic hypothesis. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2017(1), 226 (2017)

Zhang, T., Ma, W., Meng, X.: Global dynamics of a delayed chemostat model with harvest by impulsive flocculant input. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2017(1), 115 (2017)

Lv, W., Wang, F., Li, Y.: Adaptive finite-time tracking control for nonlinear systems with unmodeled dynamics using neural networks. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2018(1), 159 (2018)

Liu, F., Xue, Q.: Characterizations of the multiple Littlewood–Paley operators on product domains. Publ. Math. (Debr.) 92(3–4), 419–439 (2018)

Terry, A.J.: Biocontrol in an impulsive predator–prey model. Math. Biosci. 256, 102–115 (2014)

Caltagirone, L.E., Doutt, R.L.: The history of the vedalia beetle importation to California and its impact on the development of biological control. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 34(1), 1–16 (1989)

Xu, W., Chen, L., Chen, S., Pang, G.: An impulsive state feedback control model for releasing white-headed langurs in captive to the wild. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 34, 199–209 (2016)

Barclay, H.J.: Models for pest control using predator release, habitat management and pesticide release in combination. J. Appl. Ecol. 19(2), 337–348 (1982)

Cheng, H., Wang, F., Zhang, T.: Multi-state dependent impulsive control for Holling I predator–prey model. Discrete Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2012(12), Article ID 181752 (2012)

Li, Y., Cheng, H., Wang, J., Wang, Y.: Dynamic analysis of unilateral diffusion Gompertz model with impulsive control strategy. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2018(1), 32 (2018)

Huang, M., Song, X., Li, J.: Modelling and analysis of impulsive releases of sterile mosquitoes. J. Biol. Dyn. 11(1), 147 (2017)

Wang, F., Zhang, X.: Adaptive finite time control of nonlinear systems under time-varying actuator failures. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. https://doi.org/10.1109/TSMC.2018.2868329

Liu, F.: A note on Marcinkiewicz integrals associated to surfaces of revolution. J. Aust. Math. Soc. 104(3), 380–402 (2018)

Wang, F., Chen, B., Sun, Y., Lin, C.: Finite time control of switched stochastic nonlinear systems. Fuzzy Sets Syst. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fss.2018.04.016

Huang, C., Cao, J., Xiao, M., Alsaedi, A., Alsaadi, F.E.: Controlling bifurcation in a delayed fractional predator–prey system with incommensurate orders. Appl. Math. Comput. 293, 293–310 (2017)

Huang, C., Cao, J., Xiao, M., Alsaedi, A., Hayat, T.: Effects of time delays on stability and Hopf bifurcation in a fractional ring-structured network with arbitrary neurons. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 57, 1–13 (2018)

Cao, J., Guerrini, L., Cheng, Z.: Stability and Hopf bifurcation of controlled complex networks model with two delays. Appl. Math. Comput. 343, 21–29 (2019)

Zhang, T., Meng, X., Liu, R., Zhang, T.: Periodic solution of a pest management Gompertz model with impulsive state feedback control. Nonlinear Dyn. 78(2), 921–938 (2014)

Sen, M., Banerjee, M., Morozov, A.: Bifurcation analysis of a ratio-dependent predator–prey model with the Allee effect. Ecol. Complex. 11(3), 12–27 (2012)

Xiao, D., Ruan, S.: Global dynamics of a ratio-dependent predator–prey system. J. Math. Biol. 43(3), 268–290 (2001)

Sun, K., Zhang, T., Tian, Y.: Theoretical study and control optimization of an integrated pest management predator–prey model with power growth rate. Math. Biosci. 279, 13–26 (2016)

Liang, Z., Pang, G., Zeng, X., Liang, Y.: Qualitative analysis of a predator–prey system with mutual interference and impulsive state feedback control. Nonlinear Dyn. 87(3), 1–15 (2016)

Tian, Y., Sun, K., Chen, L.: Geometric approach to the stability analysis of the periodic solution in a semi-continuous dynamic system. Int. J. Biomath. 7(2), 121–139 (2014)

Funding

The paper was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 11371230), Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation, China (No. S2015SF002), SDUST Research Fund (2014TDJH102), and Joint Innovative Center for Safe and Effective Mining Technology and Equipment of Coal Resources, Shandong Province of China.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Shi, Z., Wang, J., Li, Q. et al. Control optimization and homoclinic bifurcation of a prey–predator model with ratio-dependent. Adv Differ Equ 2019, 2 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-018-1933-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13662-018-1933-z