Abstract

Background

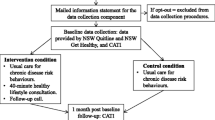

People with a mental illness experience a higher morbidity and mortality from chronic diseases relative to the general population. A higher prevalence of risk behaviours, including tobacco smoking, poor nutrition, harmful alcohol consumption and physical inactivity, is a substantial contributor to this health inequity. Clinical practice guidelines recommend that mental health services routinely provide care to their clients to address these risk behaviours. Such care may include the following elements: ask, assess, advise, assist and arrange (the ‘5As’), which has been demonstrated to be effective in reducing risk behaviours. Despite this potential, the provision of such care is reported to be low internationally and in Australia, and there is a need to identify effective strategies to increase care provision. The proposed review will examine the effectiveness of interventions which aimed to increase care provision (i.e. increase the proportion of clients receiving or clinicians providing the 5As) for the chronic disease risk behaviours of clients within the context of mental health service delivery.

Methods

Eligible studies will be any quantitative study designs with a comparison group and which report on the effectiveness of an intervention strategy (including delivery arrangements, financial arrangements, governance arrangements and implementation strategies) to increase care provision specifically for chronic disease risk behaviours (tobacco smoking, poor nutrition, harmful alcohol consumption and physical inactivity). Screening for studies will be conducted across seven electronic databases: PsycINFO, MEDLINE, Excerpta Medica database (EMBASE), Psychology and Behavioural Sciences Collection, Scopus, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL). Two authors will independently screen studies for eligibility and extract data from included studies. Where studies are sufficiently homogenous, meta-analysis will be performed. Where considerable heterogeneity exists (I2 ≥ 75), narrative synthesis will be used.

Discussion

This review will be the first to synthesise evidence for the effectiveness of intervention approaches to facilitate care provision for chronic disease risk behaviours in the context of mental health service delivery. The results have the potential to inform the development of evidenced-based approaches to address the health inequities experienced by this population group.

Systematic review registration

PROSPERO CRD42017074360.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In Australia, the gap in life expectancy for people with a mental illness is estimated to be 16 years for males and 12 years for females, with approximately 78% of this excess death being attributable to physical health conditions such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes and cancer [1]. A higher prevalence of modifiable risk behaviours including tobacco smoking, poor nutrition, physical inactivity and harmful alcohol consumption has been reported among people with a mental illness across multiple settings and psychiatric diagnoses, relative to the general population [2,3,4]. These risk behaviours contribute substantially to the higher morbidity and mortality from chronic diseases, and subsequently reduced life expectancy, experienced by this population group internationally [4,5,6,7,8].

The importance of assessing and managing the chronic disease risk behaviours of people with a mental illness within clinical practice is recognised in international best practice and clinical guidelines [2, 9, 10]. Moreover, it has been well recognised that there are opportunities to provide evidence-based preventive care for health risk behaviours systematically and routinely for a large proportion of persons with a mental illness within mental health care settings [11,12,13]. To address risk behaviours within clinical consultations generally, systematic review evidence [14,15,16,17] supports five recommended care elements in the ‘5As’ approach (ask, assess, advise, assist and arrange) (see Table 1 for definitions of the ‘5As’ elements), with some recent support also for an abbreviated ‘2As and an R’ model (ask, advice and refer), further recognising the need to manage time constraints and competing clinical priorities [18,19,20]. Provision of this care has been reported to be effective in reducing risk behaviours [21,22,23,24]; however, the provision of such care for chronic disease risks within mental health treatment settings is consistently reported to be sub-optimal in Australia [25,26,27,28] and internationally [29,30,31]. As such, there is a need to identify strategies to improve the delivery of this evidence-based care within mental health services.

Cochrane review evidence has suggested that a range of intervention strategies may increase adherence to clinical practice guidelines and policies generally, including electronic reminder systems [32, 33], education and training for staff [34], monitoring clinician behaviours and providing feedback [35] and coordination of care among multiple providers [36]. The Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) taxonomy for health systems interventions identifies the following domains for categorising intervention strategies which aim to improve health care delivery: delivery arrangements (changes in who is responsible for care provision or how, when or where care is delivered), financial arrangements (changes in funding, insurance, purchasing of services and use of financial incentives), governance arrangements (changes in rules or processes such as policy changes) and implementation strategies (strategies to change the behaviour of healthcare organisations or clinicians, or the use of health services by clients) [37]. Although studies have shown such strategies to be effective in increasing provision of care specifically for chronic disease risk behaviours in general health settings [38,39,40], less is known about the effectiveness of these strategies within mental health service settings. The studies which have been conducted have trialled a range of intervention strategies [41] and have reported varied effectiveness. Strategies trialled with some effect in improving the provision of care for health risks in the context of mental health service delivery include delivery arrangements (such as additional specialist roles to support care provision [42, 43] and the co-location of mental and physical health services [44]) and implementation strategies (such as multi-strategy practice change interventions incorporating electronic reminder systems, staff education and training and clinician monitoring and feedback to encourage care provision with routine consultations of mental health services [45, 46]).

Two previous systematic reviews were identified that examined the effectiveness of intervention strategies to increase the delivery of physical health care in mental health settings [47, 48]. The first, a systematic review by Druss and von Esenwein [48], included studies of any design which aimed to improve linkage to and/or the quality of primary medical care for people with a mental illness, including screening, diagnosis and management of medical conditions (including hypertension, tuberculosis, sexually transmitted diseases and arthritis). A range of intervention approaches were identified, including training mental health staff to provide medical services, additional consultations with staff specifically to provide medical care and facilitated referrals to dedicated primary care services. Five of the six studies identified reported a statistically significant improvement in the number of appointments clients attended with a general medical provider following intervention. The second review, by Cerimele and Strain [47], reviewed interventions of any design which utilised one implementation strategy, placing a primary care provider in mental health settings, and identified four studies variously addressing biological (e.g. blood pressure weight and lipid screening) and behavioural chronic disease risks (e.g. tobacco smoking, poor nutrition, physical inactivity and substance use). From a narrative synthesis, the authors concluded that placing primary care providers in mental health settings may be effective in improving care provision (screening and counselling/advice), coordination of care with other health professionals and client health outcomes for biological (lipid screening, cancer screening, pap testing, blood pressure, and weight) and/or behavioural risks (tobacco smoking, substance use, nutrition, physical activity). Neither systematic review reported on the effectiveness of multiple intervention strategies in increasing the provision of care specifically for behavioural risks.

Given the absence of a systematic review synthesising the effectiveness of interventions in increasing care for behavioural chronic disease risks specifically within the context of mental health service delivery, and the range of intervention strategies [41] and varied effectiveness reported in individual studies to date, synthesis of the effectiveness of such intervention strategies is warranted.

Objective

The aim of this review is to determine the effectiveness of interventions [37] designed to increase the provision of care (at least one component of the 5As) to address the chronic disease risk behaviours (tobacco smoking, poor nutrition, harmful alcohol consumption and physical inactivity) of clients within the context of mental health service delivery.

Methods

All methods employed in the review will be consistent with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [49]. This protocol has been reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) [50] (see Additional file 1 for the populated PRISMA-P checklist).

Eligibility criteria

Study design

Any quantitative study designs with a comparison group (usual care, no intervention or any alternative intervention) will be considered, such as randomised controlled trials including cluster randomised controlled trials, quasi-randomised trials and pre-post and interrupted time-series trials. Any studies without a comparison group will be excluded. There will be no restriction based on length of follow-up.

Participants

Services whose primary objective is to support the health and well-being of adults with a mental illness (i.e. predominantly over the age of 18) will be eligible. This may include three types of mental health services: bed-based (inpatient overnight acute residential care services); specialised community mental health care (including outpatient services such as community mental health services, clinical psychologists and private psychiatrists); and community-based mental health support services (non-clinical mental health services that support people with a mental illness to live independently in the community, including residential respite care, group and individual support and rehabilitation services, non-governmental mental health organisations and community managed organisations). Settings exclusively providing care for substance use will be excluded.

Interventions

To be eligible, studies must have aimed to increase the delivery of at least one preventive care element (ask, assess, advise, assist and arrange) for at least one of the four key chronic disease risk behaviours (tobacco smoking, poor nutrition, harmful alcohol consumption and/or physical inactivity). In order to be considered, the intervention must have aimed to increase the delivery of care within the context of mental health care delivery, by staff or clinicians of the service. Studies where research staff provide the care will be excluded.

All types of intervention strategies will be considered. These include, but are not limited to, delivery arrangements (such as additional personnel to support the provision of care), financial arrangements (such as changes to funding and insurance schemes), governance arrangements (such as policy changes), and implementation strategies (such as audit and feedback, electronic tools and education and training for staff) [37]. Interventions may be singular or multi-component.

Primary outcomes

Studies will be included if they quantitatively assess the provision or receipt of at least one care element (ask, assess, advice, assist and arrange) for at least one chronic disease risk behaviour (tobacco smoking, poor nutrition, harmful alcohol consumption or physical inactivity) in the context of mental health service delivery. Use of the 5As terminology for the elements of care will not be required and will be inferred by the extractor based on definitions [20, 51] of the 5As [52]. Broadly, ask will be asking clients about their current behaviour levels for at least one of the risk behaviours. Assessment will be considered assessing readiness to change and/or dependence (for tobacco smoking and alcohol consumption). Advice will include any type of advice to change behaviours or education around the individual’s level of risk, the definitions of risk and/or guidelines for behaviours. Assist may include discussing the benefits of and barriers to change, providing counselling to change behaviours such as motivational interviewing and/or providing additional supports such as pharmacotherapy or educational materials. Arrange will include making a referral to any health care provider or support service to address behaviour change such as a telephone support service, dietician or support group [20, 51]. How the risk behaviours are operationalised will be dependent on how each study defines such behaviours. For instance, poor nutrition may include markers such as daily energy intake, sodium intake, saturated fat intake or insufficient fruit and vegetable consumption.

Outcomes can be reported as absolute care provision or receipt (e.g. the percentage of clients provided an element of care before and after an intervention) or a relative change in the provision or receipt of care. Data may be derived from a variety of sources such as client report, clinician report, medical record audit or administrative records. For studies reporting multiple follow-up assessments, data will be extracted for the final follow-up point.

Outcome data that reports the provision or receipt of care for an individual behavioural risk, or combined with multiple behavioural risks will be extracted. Where outcome data is combined for multiple risks that includes both behavioural and non-behavioural risks (e.g. tobacco smoking and blood pressure) and the impact of the intervention on behavioural risks cannot be extracted separately to non-behavioural risks, that data will not be extracted. Corresponding authors will be contacted to determine if any data for individual risk behaviours can be provided.

Secondary outcomes

1. Measures of client risk behaviours including tobacco smoking, nutrition, alcohol consumption and physical activity levels. These measures could be collected from a variety of sources such as client report, clinician report following an assessment, medical records, observation and biochemical measures.

2. Any estimate of the costs and/or cost effectiveness of intervention strategies to improve the delivery of care for chronic disease risk behaviours provided in mental health settings.

Publication characteristics

There will be no exclusion criteria based on the country where a study was undertaken. Included studies must be published in English and have been published from 1998 to present. Given that implementation science is a relatively new field, this timeframe is sufficient to capture all relevant research.

Information sources

Electronic databases

The following electronic databases will be searched: PsycINFO, MEDLINE, Excerpta Medica database (EMBASE), Psychology and Behavioural Sciences Collection, Scopus, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL).

Other sources

Hand searches will be conducted on the reference lists of included studies: the first 200 citations of Google Scholar and four relevant journals in the field from the past 3 years (Psychiatric Services, Implementation Science, British Journal of Psychiatry Bulletin and BMC Health Services Research). Experts in the field will also be consulted for additional references. Authors of included studies will be contacted to check for further related publications and potential studies.

Search strategy

The search strategy will include terms for (a) the study setting (e.g. mental health service, psychosocial support service, community mental health), (b) the four risk behaviours (tobacco smoking, poor nutrition, physical inactivity and harmful alcohol consumption), and (c) the study type (intervention or implementation studies). Search filters will be included for mental health service types and risk behaviours that were used in other, similar systematic reviews [52, 53]. Search terms for study type (interventions and implementation studies) will be adapted from a glossary for dissemination and implementation research [54] and similar systematic reviews [55]. The search strategy will be adapted for each database as required (see Additional file 2 for the draft search strategy for MEDLINE).

Study records

Data management

EndNote will be used to remove duplicates, to assist in obtaining full-text papers and to store and manage review records. RevMan software will be used for pooling of trial data and meta-analyses.

Selection of studies

Duplicate articles will be removed. Two reviewers will independently assess the titles and abstracts of studies identified using the above search strategy to determine their eligibility based on the inclusion criteria. The reviewers will not be blinded to author name, author study institution or journal title. Articles that do not meet inclusion criteria will be excluded. The full texts of the remaining papers will be obtained and assessed independently by two reviewers to determine study eligibility. Any disagreement between the two reviewers regarding study eligibility will be resolved via consensus or, if required, a third reviewer. Where there is no sufficient study details, corresponding authors will be contacted for further details to determine study eligibility. If sufficient information remains unavailable, the study will be deemed ineligible.

Data collection process

Two study reviewers will independently extract data for each included study using a standardised form which will be piloted. Disagreements regarding data extraction will be resolved through consensus between the two authors or by a third author where discrepancies remain unresolved. Where there is insufficient data reported for primary outcomes, corresponding authors will be contacted for clarification. One review author will transcribe data from eligible studies into RevMan software using data extraction forms, and a second author will check this process [56,57,58]. The following information will be extracted:

-

Author and year of publication, study design, mental health service type, country and participant/service demographics.

-

Characteristics of the intervention including intervention and comparison group conditions, intervention duration and intensity, type of intervention [37], strategies implemented, who delivered the intervention (e.g. all staff, select staff or a single staff member), target of the intervention (who was expected to provide the care), care element(s), health behaviour(s) addressed, any policy that the mental health service had with regard to chronic disease behaviour care and measures related to intervention fidelity.

-

Data pertaining to primary and secondary outcomes including data source/collection method, data collection time point, effect size and measures of outcome variability.

-

Information required for assessment of potential study bias (see Assessment of risk of bias).

Assessment of risk of bias

For randomised controlled trials, risk of bias for each included study will be assessed independently by two review authors against the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions study characteristics including selection bias (sequence generation and allocation concealment), performance bias (blinding of participants and personnel), detection bias (blinding of outcome assessment), attrition bias (incomplete outcome data), reporting bias (selective reporting) and other potential sources of bias [49]. For non-randomised controlled trials, potential confounding will be assessed [49]. Risk of bias for cluster-randomised trials will be assessed against additional criteria, including recruitment to cluster, baseline imbalance, loss of clusters and incorrect analysis [49]. Any additional biases specific to individual study designs will be assessed by the reviewers and reported.

Data analysis

Where studies are sufficiently homogenous (I2 < 75%; chi-square p > 0.1), a random effects meta-analysis will be performed for each element of care (ask, assess, advise, assist and arrange) by the four risk behaviours (tobacco smoking, poor nutrition, harmful alcohol consumption and physical inactivity). Continuous outcomes will be pooled and reported as a mean difference where consistent measures are used or a standardised mean difference where different measures are used to report a comparable outcome. Binary outcomes will be pooled and effect estimate reported using odds ratios. Where possible, sub-group analyses will be conducted for different intervention strategies, mental health service type and the four risk behaviours. A sensitivity analysis will be conducted to exclude studies which are categorised as high risk of bias. Where studies are not sufficiently homogenous, trial outcomes will be described narratively.

Assessment of study heterogeneity

Heterogeneity will be assessed via visual inspection of forest plots and consideration of the I2 statistic. Where considerable heterogeneity is found (I2 ≥ 75) [49], the sources of heterogeneity will be investigated through sub-group analysis on study setting (mental health service type), design, outcomes and interventions.

Issues of clustering

For any included cluster randomised controlled trials, adjustments will be made for unit of analysis error by applying intraclass correlation values. If not reported, intraclass correlations will be requested from corresponding authors, and if they remain unavailable, estimates from similar studies will be used to adjust for clustering [49].

Assessment of reporting bias

Funnel plots will be used to determine possible reporting bias in included studies.

Confidence in cumulative evidence

The strength of the body of evidence will be assessed using the GRADE approach developed by the Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation Working Groups [59]. This approach includes assessment of each individual outcome per trial across five key areas: risk of bias within included studies (methodological quality), directness of evidence (relevance to the review question), heterogeneity (inconsistency), precision of effect estimates, and risk of publication bias.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics approval is not required. The findings of this review will be disseminated via publication of the final review manuscript and conference presentations.

Discussion

This systematic review will be the first to examine the effectiveness of interventions to increase care provision for chronic disease risk behaviours in mental health settings. The high prevalence of chronic disease risk behaviours among persons with a mental illness is contrasted with a low prevalence of care. An effective intervention approach to facilitate the delivery of care for chronic disease risk behaviours within the context of mental health service delivery has the potential to reduce their high prevalence and consequently reduce the chronic disease burden experienced by persons with a mental illness. The synthesis of evidence in this review will provide clarity around the effectiveness of such interventions. The findings hold the potential to translate into effective implementation strategies to improve the quality of care for reducing health risk behaviours among clients of mental health services.

Abbreviations

- 2As and an R:

-

Assess, advise and refer

- 5As:

-

Ask, assess, advise, assist and arrange

- CENTRAL:

-

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials

- CINAHL:

-

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature

- EMBASE:

-

Excerpta Medica database

References

Lawrence D, Hancock KJ, Kisely S. The gap in life expectancy from preventable physical illness in psychiatric patients in Western Australia: retrospective analysis of population based registers. BMJ. 2013;346:f2539.

Galletly C, Castle D, Dark F, Humberstone V, Jablensky A, Killackey E, et al. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for the management of schizophrenia and related disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2016;50(5):410–72.

Kilbourne AM, Morden NE, Austin K, Ilgen M, McCarthy JF, Dalack G, et al. Excess heart-disease-related mortality in a national study of patients with mental disorders: identifying modifiable risk factors. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2009;31(6):555–63.

Robson D, Gray R. Serious mental illness and physical health problems: a discussion paper. Int J Nurs Stud. 2007;44(3):457–66.

Lawrence D, Kisely S, Pais J. The epidemiology of excess mortality in people with mental illness. Can J Psychiatr. 2010;55(12):752–60.

Druss BG, Walker ER. Mental disorders and medical comorbidity. Synth Proj Res Synth Rep. 2011;21:1–26.

Walker E, McGee RE, Druss BG. Mortality in mental disorders and global disease burden implications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiat. 2015;72(4):334–41.

Colton CW, Manderscheid RW. Congruencies in increased mortality rates, years of potential life lost, and causes of death among public mental health clients in eight states. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;3(2):A42.

RACGP. Smoking, nutrition, alcohol and physical activity: a population health guide to behavioural risk factors in general practice. Melbourne: RACGP; 2004.

US Preventive Services Task Force. Guide to clinical preventive services. Rockville: AHRQ; 2009.

NSW department of health. Physical Health Care of Mental Health Consumers: guidelines. Sydney: NSW Ministry of Health; 2009.

Royal College of Psychiatrists. Improving physical health for people with a mental illness: what can be done? Faculty report FR/GAP/01. London: Royal College of Psychiatrists; 2013.

Welsh Assembly Government. The role of community mental health teams in delivering community mental health services: interim policy implementation guidance and standards. Wales: Welsh Assembly Government; 2010.

Brunner EJ, Rees K, Ward K, Burke M, Thorogood M. Dietary advice for reducing cardiovascular risk. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(Issue 4):CD002128.

Kaner EF, Beyer F, Dickinson HO, Pienaar E, Campbell F, Schlesinger C, et al. Effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions in primary care populations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(Issue 2):CD004148.

Stead LF, Bergson G, Lancaster T. Physician advice for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008(2).

Papadakis S, McDonald P, Mullen K-A, Reid R, Skulsky K, Pipe A. Strategies to increase the delivery of smoking cessation treatments in primary care settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev Med. 2010;51(3–4):199–213.

Revell CC, Schroeder SA. Simplicity matters: using system-level changes to encourage clinician intervention in helping tobacco users quit. Nicotine Tob Res. 2005;7(Suppl 1):S67–9.

Glasgow RE, Goldstein MG, Ockene JK, Pronk NP. Translating what we have learned into practice. Principles and hypotheses for interventions addressing multiple behaviors in primary care. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27(2 Suppl):88–101.

Schroeder SA. What to do with a patient who smokes. JAMA. 2005;294(4):482–7.

Quinn VP, Hollis JF, Smith KS, Rigotti NA, Solberg LI, Hu W, et al. Effectiveness of the 5-As tobacco cessation treatments in nine HMOs. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(2):149–54.

Rueda-Clausen C, Benterud E, Bond T, Olszowka R, Vallis TM, Sharma AM. Effectiveness of Implementing The 5As of Obesity Management™ in a primary care setting. Can J Diabetes. 37:S282.

Whitlock EP, Orleans CT, Pender N, Allan J. Evaluating primary care behavioral counseling interventions: an evidence-based approach. Am J Prev Med. 2002;22(4):267–84.

Goldstein MG, Whitlock EP, DePue J. Multiple behavioral risk factor interventions in primary care. Summary of research evidence. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27(2 Suppl):61–79.

Bartlem KM, Bowman JA, Freund M, Wye PM, McElwaine KM, Wolfenden L, et al. Care provision to prevent chronic disease by community mental health clinicians. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(6):762–70.

Bartlem K, Bowman J, Freund M, Wye P, Lecathelinais C, McElwaine K, et al. Acceptability and receipt of preventive care for chronic-disease health risk behaviors reported by clients of community mental health services. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66(8):857–64.

Happell B, Platania-Phung C, Scott D. Are nurses in mental health services providing physical health care for people with serious mental illness? An Australian perspective. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2013;34(3):198–207.

Johnson K, Fry CL. The attitudes and practices of community managed mental health service staff in addressing physical health: findings from a targetted online survey. Adv Ment Health. 2013;11(2):163–71.

Chwastiak L, Cruza-Guet MC, Carroll-Scott A, Sernyak M, Ickovics J. Preventive counseling for chronic disease: missed opportunities in a community mental health center. Psychosomatics. 2013;54(4):328–35.

Johnson JL, Malchy LA, Ratner PA, Hossain S, Procyshyn RM, Bottorff JL, et al. Community mental healthcare providers’ attitudes and practices related to smoking cessation interventions for people living with severe mental illness. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;77(2):289–95.

Robson D, Haddad M, Gray R, Gournay K. Mental health nursing and physical health care: a cross-sectional study of nurses’ attitudes, practice, and perceived training needs for the physical health care of people with severe mental illness. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2013;22(5):409–17.

Arditi C, Rege-Walther M, Wyatt JC, Durieux P, Burnand B. Computer-generated reminders delivered on paper to healthcare professionals; effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12:CD001175.

Shojania KG, Jennings A, Mayhew A, Ramsay CR, Eccles MP, Grimshaw J. The effects of on-screen, point of care computer reminders on processes and outcomes of care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(Issue 3):CD001096.

Forsetlund L, Bjorndal A, Rashidian A, Jamtvedt G, O'Brien MA, Wolf F, et al. Continuing education meetings and workshops: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(Issue 2):CD003030.

Jamtvedt G, Young JM, Kristoffersen DT, O’Brien MA, Oxman AD. Audit and feedback: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(Issue 2):CD000259.

Gillies D, Buykx P, Parker AG, et al. Consultation liaison in primary care for people with mental disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(Issue 9):CD007193.

Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC). EPOC taxonomy. 2015. Available at: https://epoc.cochrane.org/epoc-taxonomy.

McElwaine KM, Freund M, Campbell EM, Knight J, Bowman JA, Wolfenden L, et al. Increasing preventive care by primary care nursing and allied health clinicians: a non-randomized controlled trial. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(4):424–34.

Borrelli B, Lee C, Novak S. Is provider training effective? Changes in attitudes towards smoking cessation counseling and counseling behaviors of home health care nurses. Prev Med. 2008;46(4):358–63.

Bakker MJ, Mullen PD, de Vries H, van Breukelen G. Feasibility of implementation of a Dutch smoking cessation and relapse prevention protocol for pregnant women. Patient Educ Couns. 49(1):35–43.

Rodgers M, Dalton J, Harden M, Street A, Parker G, Eastwood A. Integrated care to address the physical health needs of people with severe mental illness: a rapid review. Health Serv Deliv Res. 2016.

Osborn DP, Nazareth I, Wright CA, King MB. Impact of a nurse-led intervention to improve screening for cardiovascular risk factors in people with severe mental illnesses. Phase-two cluster randomised feasibility trial of community mental health teams. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10(1):1–13.

McKenna B, Furness T, Wallace E, Happell B, Stanton R, Platania-Phung C, et al. The effectiveness of specialist roles in mental health metabolic monitoring: a retrospective cross-sectional comparison study. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:234.

Druss BG, Rohrbaugh RM, Levinson CM, Rosenheck RA. Integrated medical care for patients with serious psychiatric illness: a randomized trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(9):861–8.

Bartlem KM, Bowman J, Freund M, Wye PM, Barker D, McElwaine KM, et al. Effectiveness of an intervention in increasing the provision of preventive care by community mental health services: a non-randomized, multiple baseline implementation trial. Implement Sci. 2016;11(1):46.

Maki M, Bjorklund P. Improving cardiovascular disease screening in community mental health centers. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2013;49(3):179–86.

Cerimele JM, Strain JJ. Integrating primary care services into psychiatric care settings: a review of the literature. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;12(6). https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.10r00971whi.

Druss BG, von Esenwein SA. Improving general medical care for persons with mental and addictive disorders: systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28(2):145–53.

Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. Available from http://handbook.cochrane.org.

Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1):1.

RACGP. Supporting smoking cessation: a guide for health professionals. 2014.

McElwaine KM, Freund M, Campbell EM, Bartlem KM, Wye PM, Wiggers JH. Systematic review of interventions to increase the delivery of preventive care by primary care nurses and allied health clinicians. Implement Sci. 2016;11(1):50.

Bailey J, Bartlem K, Wiggers J, Wye P, Regan T, Stockings E, et al. Systematic review of the prevalence of preventive care provision for chronic disease risk behaviours in mental health services. 2016;PROSPERO: CRD42016049889 Available from http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.asp?ID=CRD42016049889

Rabin BA, Brownson RC, Haire-Joshu D, Kreuter MW, Weaver NL. A glossary for dissemination and implementation research in health. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2008;14(2):117–23.

Wolfenden L, Jones J, Williams CM, Finch M, Wyse RJ, Kingsland M, et al. Strategies to improve the implementation of healthy eating, physical activity and obesity prevention policies, practices or programmes within childcare services. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;10:CD011779.

Dray J, Bowman J, Campbell E, Freund M, Wolfenden L, Hodder RK, et al. Systematic review of universal resilience-focused interventions targeting child and adolescent mental health in the school setting. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017.

Stead LF, Koilpillai P, Fanshawe TR, Lancaster T. Combined pharmacotherapy and behavioural interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;3:CD008286.

Cahill K, Hartmann-Boyce J, Perera R. Incentives for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(Issue 5):CD004307.

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336(7650):924–6.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Debbie Booth for her help in designing the search strategy for the present review.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JB, KB, JW and CF developed the research question. CF led the drafting of the review protocol and development and refinement of the search strategy and will lead the review. JBow, KB, LW and JD contributed to the refinement of the manuscript through critical review and contributed to the refinement of the search strategy. JW, TR and JBai contributed to the refinement of the manuscript through critical review. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

PRISMA-P 2015 populated Checklist. (DOCX 23 kb)

Additional file 2:

Draft search strategy for MEDLINE. (DOCX 28 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Fehily, C., Bartlem, K., Wiggers, J. et al. Systematic review of interventions to increase the provision of care for chronic disease risk behaviours in mental health settings: review protocol. Syst Rev 7, 67 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-018-0735-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-018-0735-4