Abstract

Background

Relative to the general population, people with a mental illness are more likely to have modifiable chronic disease health risk behaviours. Care to reduce such risks is not routinely provided by community mental health clinicians. This study aimed to determine the effectiveness of an intervention in increasing the provision of preventive care by such clinicians addressing four chronic disease risk behaviours.

Methods

A multiple baseline trial was undertaken in two groups of community mental health services in New South Wales, Australia (2011–2014). A 12-month practice change intervention was sequentially implemented in each group. Outcome data were collected continuously via telephone interviews with a random sample of clients over a 3-year period, from 6 months pre-intervention in the first group, to 6 months post intervention in the second group. Outcomes were client-reported receipt of assessment, advice and referral for tobacco smoking, harmful alcohol consumption, inadequate fruit and/or vegetable consumption and inadequate physical activity and for the four behaviours combined. Logistic regression analyses examined change in client-reported receipt of care.

Results

There was an increase in assessment for all risks combined following the intervention (18 to 29 %; OR 3.55, p = 0.002: n = 805 at baseline, 982 at follow-up). No significant change in assessment, advice or referral for each individual risk was found.

Conclusions

The intervention had a limited effect on increasing the provision of preventive care. Further research is required to determine how to increase the provision of preventive care in community mental health services.

Trial registration

Australian and New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry ACTRN12613000693729

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Background

People with a mental illness experience a disproportionately higher chronic disease burden when compared to the general population and a substantially reduced life expectancy as a consequence [1–7]. Such poor health outcomes are contributed to by a higher prevalence of modifiable chronic disease health risk behaviours, including smoking [8–13], inadequate nutrition [13–16], harmful alcohol consumption [8, 13, 14, 17, 18] and inadequate physical activity [9, 13, 17, 19, 20].

Routine care delivery by clinicians to address chronic disease risk behaviours (preventive care) is recommended for all health services [21–27], including mental health services [28–39]. Such care is recommended to involve, at a minimum, clinician assessment of client risk status and, for clients identified as being at risk, provision of advice and referral to specialist preventive care services [40, 41]. Although community mental health services represent a key setting for the provision of preventive care [42], the provision of such care in this setting is both variable and sub-optimal [42–47].

Cochrane systematic review evidence supports the efficacy of a range of strategies in improving the provision of recommended elements of clinical care, with such strategies including leadership and consensus [48], enablement of systems and procedures [49–51], training and education [52], monitoring and feedback [53, 54], provision of practice change resources such as educational materials and clinical practice guidelines [55] and practice change support such as educational outreach or academic detailing [56]. In intervention trials in general health services, implementation of such strategies has been associated with increases in care delivery for smoking [57–62], at-risk alcohol consumption [63] and multiple health risk behaviours [64].

Only one study could be identified that assessed the effectiveness of a practice change intervention in increasing the provision of preventive care for multiple health risks in a community mental health setting [65]. A single group pre-post study was undertaken in two USA services of a 6-month intervention to increase the provision of risk assessment regarding a number of cardiovascular disease risks (tobacco smoking and non-behavioural risks e.g. blood pressure and cholesterol) and the sending of a letter to clients’ primary care providers. The intervention practice change strategies included staff education, an electronic screening tool and a template for a standard communication letter. A random sample of clients’ medical records was audited before (n = 129) and after (n = 117) the intervention. The proportion of clients screened for smoking by psychiatrists, mental health nurses and case managers increased from 76 to 89 %, while the proportion of clients for whom a letter was sent to their primary care provider increased from 19 to 32 % [65].

Further research is needed to examine whether a practice change intervention can improve the provision of a broader range of preventive care elements for the most common chronic disease risk behaviours. To address this need, a study was undertaken to determine the effectiveness of a multi-strategic practice change intervention in increasing the provision of three elements of preventive care (risk assessment, brief advice and referral) by community mental health clinicians for four health risk behaviours (smoking, inadequate fruit and vegetable consumption, harmful alcohol consumption and inadequate physical activity).

Methods

Study design and setting

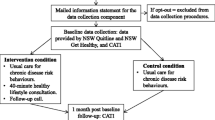

A multiple baseline trial [66] was undertaken involving a 12-month intervention delivered sequentially in two groups of community-based mental health services. Outcome data were collected for both groups from 6 months prior to the implementation of the intervention in the first group of services, and continued until 6 months after the completion of the intervention in the second group of services (36-month study period). Further details of the study design and methods have been reported previously [67]. The study was undertaken in a single regional health district in New South Wales, Australia. Ethics approval was obtained from the Hunter New England Human Research Ethics Committee (approval no. 09/06/17/4.03) and the University of Newcastle Human Research Ethics Committee (approval no. H-2010-1116). The trial was registered with the Australian and New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN12613000693729).

Participants

Community mental health services

All community mental health services (n = 19) in the health district that provided ambulatory care to clients 18 years of age or greater, and were not involved in a pilot of this study, were included and allocated to two service groups (n = 7; n = 12) based on their geographic location and associated administrative boundaries. The services provided general adult community mental health care, and care for specific client populations, including older persons, psychiatric rehabilitation, early diagnosis, comorbid substance use, eating disorders and borderline personality disorder.

Clinicians

All clinicians and managers in the eligible services (psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, dietitians, nurses, occupational therapists and health service managers) received the intervention. The services were staffed with approximately 220 clinicians, predominantly nurses (40 %), psychiatrists (15 %) and psychologists (15 %).

Clients

All clients who attended a face-to-face individual clinical appointment were eligible to receive preventive care.

Clients were eligible to be selected for data collection if they were 18 years or older, had attended at least one face-to-face individual appointment with an eligible service within the previous 2 weeks, had not previously been selected to participate in the study and had not been identified by their clinician as too unwell to participate. Of such clients, additional eligibility criteria were as follows: English speaking, not living in aged care facilities or gaol and being physically and mentally capable of responding to the survey items.

Intervention

Preventive care

Clinicians were asked to routinely provide preventive care based on the recommended ‘2As and R’ model, a model that includes three elements of care [40, 68, 69]:

Assessment

Assessment of client risk status for each of the four health risk behaviours based on levels of risk defined in Australian national guidelines [70–73]

Brief advice

Provision of advice to clients assessed as being at-risk to modify their risk to comply with the Australian national guidelines [70–73] and the benefits of doing so

Referral

Offer of a referral for clients with risks to evidence-based state-wide telephone support services for smoking (New South Wales [NSW] Quitline) and for physical inactivity and inadequate nutrition (NSW Get Healthy Service). For all risk behaviours, referral could additionally be provided to the client’s primary care provider (general practitioner or Aboriginal medical service) or local referral options (e.g. dietitians, exercise groups and drug and alcohol services)

Practice change intervention

The following multi-strategic clinical practice change intervention, informed by research and reviews of the clinical practice change literature [48, 52, 53, 55, 74], was implemented:

-

1.

Leadership and consensus

A district-wide policy and key performance indicators regarding the provision of preventive care were implemented based on consultation with health district executives, senior clinicians and managers.

-

2.

Enabling systems and procedures

A tool was incorporated into the electronic medical record used by all clinicians to enable standardized assessment and recording of risk status and subsequent provision of preventive care; the automated production of a tailored client risk reduction information sheet and referral letter to the clients’ primary care provider; and prompts to deliver brief advice and referral where clients were identified as at-risk.

-

3.

Clinician and manager training

Clinicians and managers were provided online educational competency-based training of approximately 2-h duration, addressing the following: the provision of preventive care, including the ‘2As and R’ model; policy guidelines and performance indicators; and the recording of such care in the standardized electronic tool. Managers were additionally provided with a 2-h, face-to-face training session regarding care delivery performance monitoring and feedback and leadership in preventive care.

-

4.

Monitoring and feedback

Modifications were made to the electronic medical record to allow automated production of monthly performance reports regarding the provision of preventive care at the service level. Reports were provided to and discussed with managers monthly.

-

5.

Provision of practice change resources

An e-mail helpline and internet resource site were established, and monthly newsletters and tip-sheets and a resource pack including a process flowchart, a guide, information on each risk behaviour, fax-based referral forms for telephone referral services, and a paper-based preventive care assessment tool for use during home visits were distributed to clinicians and managers.

-

6.

Practice change support

Project personnel (approximately one full time equivalent per group) were allocated to support intervention delivery, including monthly face-to-face visits with managers and clinicians, and fortnightly support phone calls and/or e-mails to managers. The project personnel discussed the feedback reports and provided both proactive and reactive support to managers and clinicians.

Data collection procedures

Recruitment

Each week, a random sample of 40 eligible adult clients (20 from each of the two groups; approximately 7 % of eligible clients per week) was drawn from the health service electronic medical records. These clients were mailed an information statement and contacted by telephone by trained interviewers, blind to group allocation, to confirm eligibility.

Eligible clients were asked to participate in a telephone interview regarding their health behaviour risk status, the preventive care they had received for such risks and a number of demographic and clinical characteristics. The interview was approximately 20 min in length.

Measures

Client characteristics

Clients reported their Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander status, highest education level attained, employment status, marital status and physical or psychiatric conditions for which they had received health care within the previous 2 months. Client age, gender, postcode, and the number of community mental health appointments within the last 12 months were obtained from the electronic medical record.

Client health behaviour risk status

Clients reported their health behaviour risk status for the month prior to seeing their community mental health clinician. Survey items were based on recommended assessment tools [75–78] and previous community surveys [13, 46, 47, 79]. In line with national guidelines, clients were defined as being at-risk if they reported smoking any tobacco products [70], consuming less than two serves of fruit or five serves of vegetables per day [72], consuming more than two standard drinks on average per day or four or more standard drinks on any one occasion [71] or engaging in less than 30 min of physical activity on at least 5 days of the week [73].

Client-reported provision of preventive care

Assessment. Clients were asked to report whether, during a community mental health appointment, a clinician had asked about their smoking status, fruit and vegetable intake, alcohol consumption and physical activity (yes, no, don’t know for each).

Brief advice. Clients classified as being at-risk for a health risk behaviour(s) based on their self-report were asked whether their community mental health clinician had advised them to modify their behaviour(s) (yes, no, don’t know for each).

Referral. Clients classified as having at least one risk were asked whether their community mental health clinician had offered to send their primary care provider a letter summarizing their health behaviour risks and the preventive care provided. Clients classified as at risk for a health risk behaviour(s) were also asked whether their clinician had provided each of the following forms of referral (‘yes, no, or don’t know’):

-

(a)

Spoke about the NSW Quitline telephone support service (for smoking); or the NSW Get Healthy Service (for clients with inadequate fruit and vegetable intake or inadequate physical activity);

-

(b)

Offered to arrange for a telephone support service (NSW Quitline or NSW Get Healthy Service) to call them;

-

(c)

Recommended speaking to their primary care provider about their health risk behaviour(s); and

-

(d)

Advised to use any other supports to make changes to their health behaviour(s) (e.g. dietitian, physical activity classes, website).

Intervention delivery

Project personnel recorded the implementation of each practice change strategy for each service on a monthly basis.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were undertaken using SAS V9.4. Residential postcode was used to classify client residential geographic location [80] and socio-economic status [81]. Chi square tests were used to compare consenters and non-consenters regarding age group, gender, remoteness, disadvantage and number of appointments. Descriptive statistics were used to describe participating client characteristics, health behaviour risk status and receipt of preventive care. For care receipt items, clients who responded ‘don’t know’ were classified as not having received care. For each of the four behaviours, referral items were combined to create a single variable reflecting receipt of any form of referral.

A variable was created to reflect client receipt of assessment for all four risk behaviours. Separate variables were also created to reflect client receipt of brief advice for all behaviours for which they were at risk and receipt of any referral for all behaviours for which they were at risk (‘all risks combined’).

Intervention effectiveness

Logistic regression models were used to examine changes in the prevalence of preventive care delivery between the baseline and follow-up periods for the two service groups combined and for each of the two service groups individually. Separate models were developed to examine change in delivery of each of the three elements of preventive care for each of the four risk behaviours and for all four behaviours combined; and for the delivery of a letter to the client’s primary care provider (16 models in total). Five models were developed for each of the assessment and brief advice outcomes, and 6 models were developed for the referral outcome. For all models, intervention effect was defined as the difference in prevalence of preventive care delivery from the baseline to the post-intervention periods, adjusted for service group, time and the number of client visits to the service in the prior 12 months (the latter added to account for any introduced selection bias). Analyses are reported using data collected during the baseline and follow-up periods. While all models were also analysed incorporating the intervention period data, as the results did not differ, the simpler method is presented. A significance level of α = 0.01 was used to adjust for multiple testing [82]. As simple random sampling of community mental health clients was used (see “Recruitment” section), there was no need to adjust for clinician, community mental health service or any other natural clustering that occurs within the community. An unadjusted analysis provides an unbiased estimate of the statistics of interest.

Results

Sample characteristics

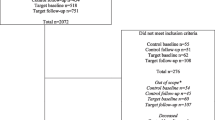

Of the 3764 clients selected to participate, 2817 were able to be contacted by telephone (75 %), and 375 were identified as ineligible upon contact. Of the 2442 eligible potential participants, 1787 (73 %) consented to participate and completed the survey (n = 805 at baseline, n = 982 at follow-up). There were no significant differences in the characteristics between consenting and non-consenting clients. Characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 1.

Intervention effectiveness

For both groups combined, there was a significant increase in the prevalence of one of the 16 outcome measures. From baseline to follow-up, there was an increase in assessment for all risks combined (18 to 29 %; OR 3.55, p = 0.002) (Table 2).

When examined separately for each of the two service groups, there was an increase in the prevalence of one outcome for group 1. From baseline to follow-up, there was an increase in the assessment of nutrition (18 to 32 %; OR 5.55, p = 0.001). No increases in care were identified for group 2 individually (Table 3).

Intervention implementation

The implementation of intervention strategies is shown in Table 4. Overall, the intervention strategies were not delivered as intended. On average per month for the two service groups combined, the proportion of services, managers or clinicians that received each strategy ranged from 63 % (performance reported discussed with managers) to 78 % (fortnightly phone/email support). Group 1 received fewer monthly intervention strategies on average. The proportion of services, managers or clinicians that received each strategy in group 1 ranged from 33 % (performance reports discussed with managers) to 69 % (face-to-face visits with clinicians), compared to 72 % (performance reports discussed with managers) to 83 % (fortnightly phone or email support for managers) in group 2 (Table 4).

Group 2 generally received one-off strategies (training and practice change resources) at an earlier stage during the intervention. For instance, the majority (80 % or more) of services in group 2 had received the resource pack by the end of month 1, compared to the end of month 4 in group 1 (Table 4).

Discussion

This is the first study to examine the effectiveness of a multi-strategy practice change intervention in increasing the provision of multiple elements of preventive care for multiple chronic disease health risk behaviours within a community mental health care setting. Overall, the study had a limited effect in increasing the provision of elements of care, with an effect observed only for the assessment of risk status for all behaviours combined. Further research is required to identify strategies for improving the delivery of chronic disease preventive care in these settings.

One previous study has examined the effectiveness of similar practice change strategies in increasing the delivery of cardiovascular disease risk screening in community mental health services [65]. The single group pre-post study conducted in the USA reported an increase in assessment of smoking status (13 %), and for providing a letter to the clients’ primary care provider (13 %). In comparison, in our controlled trial, we found an effect for assessment across risks, but not smoking, and not for providing a letter to the primary care provider. The absence of a control group in the previous study precludes a direct comparison of effect between the two studies.

The intervention in the current study involved the use of practice change strategies previously found to be effective in general health care services but not trialled in mental health services [57–64]. Importantly, the same intervention strategies were implemented in a contemporaneous study conducted in general community health services (addressing physical health care) within the same health district in which the current study was conducted [64]. That study found, using the same outcome measures and intervention approach, increases in care provision for six out of ten assessment and advice measures of preventive care (assessment of fruit and vegetable consumption, physical activity and for all risks; and brief advice for inadequate fruit and vegetable consumption, harmful alcohol consumption and for all risks [64]). However, consistent with this trial, no effect was found for provision of any element of smoking care or of referral.

The need to address the clinical, professional, cultural and organizational factors [83–85] that distinguish community mental health service delivery from the delivery of general community health services may have contributed to the contrasting findings. The findings suggest that a greater understanding of the context and barriers to the provision of preventive care in community mental health services is required. Similarly, tailoring of recommendations regarding the provision of care addressing chronic disease risk behaviours that can be operationalized in the context and circumstances of community mental health services also appears warranted, as does tailoring of the practice change strategies to support the delivery of such care. The use of systematic and theory-based methods for identifying barriers and designing interventions, such as the Theoretical Domains Framework [86], may provide a useful approach to achieving this.

No increases in either brief advice or referral were identified for any of the four health risk behaviours. Such findings are of significance as any benefit in terms of reduction in risk of chronic disease is dependent upon either or both of these elements of care [40, 41, 87]. Both elements of care have been shown to be effective in reducing the prevalence of health risks for clients of general health services [88–96]. Previous research has identified a number of barriers to mental health clinician provision of risk advice, including clinician attitudes regarding their role in providing preventive care [97–99] and a lack of training in how to provide preventive care [42, 97]. Previous research has also identified a lack of referral options as a barrier to mental health clinicians providing referrals [47, 100]. The current study sought to address barriers to both elements of preventive care through a comprehensive suite of practice change strategies including a policy, electronic prompts, fax referral forms to free public evidence-based specialist risk reduction services, automated production of referral letters to primary care providers, clinician training and education, monthly performance monitoring feedback reports and allocated practice change support personnel for 12 months. Notwithstanding the comprehensiveness of these strategies, they may not have been of a sufficient dose (e.g. frequency of contact with allocated practice change support) or of sufficient length.

Additional factors also may have impeded the clinicians’ ability to refer clients. In USA primary care services, additional strategies have been found to be effective in increasing referrals to tobacco quitlines and community behavioural counselling services including the use of financial incentives [101], and automatic, electronic referral processes [102]. However, the effectiveness of these strategies in increasing referrals regarding chronic disease risk behaviours is yet to be examined in community mental health services.

The study outcomes should be interpreted in light of a number of its methodological characteristics. First, although the study was conducted across a number of community mental health services in urban, regional and rural locations, all the services were located within one health district, potentially limiting the generalizability of findings to other jurisdictions. Second, the main outcome measure was based on client-reported receipt of preventive care. The extent to which the receipt of such care in this study is either an over- or under-estimate of the care received, particularly amongst people with a mental illness is unknown [103, 104]. Direct comparison between client report outcomes and the monthly performance reports was not possible; however, the authors can confirm that the performance reports were consistent with the pattern of results reported. Third, systematic review evidence has suggested that inadequate implementation fidelity and integrity may be explanatory factors in trials that fail to show an effect [105]. In the current trial, not all intervention strategies were implemented as planned (Table 4), and there was inconsistent implementation of the intervention between the two groups. It is unknown what impact this may have had on the trial outcomes.

Conclusions

The observed lack of an increase in preventive care provision for almost all outcome measures suggests that an intervention better tailored to the circumstances of community mental health services may be required, or one that is more intensive or includes a longer intervention period, or that an alternative model of delivering preventive care to clients of community mental health services may be required. Regardless of the specific approach, the need for a greater understanding of the barriers and facilitators to the provision of preventive care in community mental health services is indicated.

References

Chang C, Hayes R, Perera G, Broadbent M, Fernandes A, Lee W, et al. Life expectancy at birth for people with serious mental illness and other major disorders from a secondary mental health care case register in London. PLoS One. 2011;6(5):e19590.

Wahlbeck K, Westman J, Nordentoft M, Gissler M, Laursen TM. Outcomes of Nordic mental health systems: life expectancy of patients with mental disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;199(6):453–8. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.110.085100.

Laursen TM. Life expectancy among persons with schizophrenia or bipolar affective disorder. Schizophr Res. 2011;131(1–3):101–4. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2011.06.008.

Lawrence D, Hancock K, Kisely S. The gap in life expectancy from preventable physical illness in psychiatric patients in Western Australia: retrospective analysis of population based registers. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 2013;346:f2539.

Amaddeo F, Barbui C, Perini G, Biggeri A, Tansella M. Avoidable mortality of psychiatric patients in an area with a community-based system of mental health care. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2007;115:320–5.

Laursen TM, Wahlbeck K, Hallgren J, Westman J, Osby U, Alinaghizadeh H, et al. Life expectancy and death by diseases of the circulatory system in patients with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia in the Nordic countries. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e67133. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0067133.

Callaghan RC, Veldhuizen S, Jeysingh T, Orlan C, Graham C, Kakouris G, et al. Patterns of tobacco-related mortality among individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or depression. J Psychiatr Res. 2014;48(1):102–10. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.09.014.

Reichler H, Baker A, Lewin T, Carr V. Smoking among in-patients with drug-related problems in an Australian psychiatric hospital. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2001;20(2):231–7.

Ussher M, Doshi R, Sampuran A, West R. Cardiovascular risk factors in patients with schizophrenia receiving continuous medical care. Community Ment Health J. 2011;47(6):688–93. doi:10.1007/s10597-011-9376-y.

Lawrence D, Mitrou F, Zubrick SR. Smoking and mental illness: results from population surveys in Australia and the United States. BioMed Central Public Health. 2009;9(1):285. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-9-285.

Lasser K, Boyd JW, Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU, McCormick D, Bor DH. Smoking and mental illness: a population-based prevalence study. JAMA. 2000;284(20):2606–10.

Lineberry TW, Allen JD, Nash J, Galardy CW. Population-based prevalence of smoking in psychiatric inpatients: a focus on acute suicide risk and major diagnostic groups. Compr Psychiatry. 2009;50(6):526–32. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2009.01.004.

Bartlem K, Bowman J, Bailey J, Freund M, Wye P, Lecathelinais C, et al. Chronic disease health risk behaviours amongst people with a mental illness. Aust NZ J Psychiatry. 2015;49(8):731–41.

Kilian R, Becker T, Kruger K, Schmid S, Frasch K. Health behavior in psychiatric in-patients compared with a German general population sample. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;114(4):242–8.

McCreadie R. Diet, smoking and cardiovascular risk in people with schizophrenia: descriptive study. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;183:534–9.

Godfrey KM, Lindamer LA, Mostoufi S, Afari N. Posttraumatic stress disorder and health: a preliminary study of group differences in health and health behaviors. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2013;12(1):30. doi:10.1186/1744-859x-12-30.

Davidson S, Judd F, Jolley D, Hocking B, Thompson M, Hyland B. Cardiovascular risk factors for people with mental illness. Aust NZ J Psychiatry. 2001;35(2):196–202.

Gratzer D, Levitan R, Sheldon T, Toneatto T, Rector N, Goering P. Lifetime rates of alcoholism in adults with anxiety, depression, or co-morbid depression/anxiety: a community survey of Ontario. J Affect Disord. 2004;79(1–3):209–15.

Ussher M, Stanbury L, Cheeseman V, Faulkner G. Physical activity preferences and perceived barriers to activity among persons with severe mental illness in the United Kingdom. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58(3):405–8.

Janney CA, Fagiolini A, Swartz HA, Jakicic JM, Holleman RG, Richardson CR. Are adults with bipolar disorder active? Objectively measured physical activity and sedentary behavior using accelerometry. J Affect Disord. 2014;152–154:498–504. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2013.09.009.

World Health Organisation. 2008–2013 Action plan for the global strategy for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2008.

United States Preventive Services Task Force. The guide to clinical preventive services 2014: recommendations of the US Preventive Services Taskforce. Report No.: 14–05158. Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2014.

National Preventive Health Taskforce. Australia: the healthiest country by 2020—National Preventative Health Strategy—the roadmap for action. Canberra, 2010.

Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Guidelines for preventive activities in general practice (The Red Book). Melbourne: Royal Australian College of General Practitioners; 2009.

Hunter New England Local Health District. Preventive care area policy statement, HNEH Pol 10_01. Hunter New England Health; 2010

Department of Health Victoria. Victorian public health and wellbeing plan 2011–2015. Melbourne: Prevention and Population Health Branch, Victorian Government, Department of Health; 2011.

Queensland Health. The health of Queenslanders 2008: prevention of chronic disease. Second report of the chief health officer Queensland. Brisbane: Queensland Health; 2008.

Stanley S, Laugharne J. Clinical guidelines for the physical care of mental health consumers. Perth: Culture and Mental Health Unit, School of Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, University of Western Australia; 2010.

Department of Health Victoria. Improving the physical health of people with severe mental illness: no mental health without physical health. Ministerial Advisory Committee on Mental Health Report. Melbourne: Victorian Government; 2011.

Queensland Health. Queensland MIND essentials: mental illness nursing documents. Brisbane: Queensland Health; 2010.

New South Wales Health. Physical health care of mental health consumers: guideline. Sydney: New South Wales Department of Health; 2009.

New South Wales Health. Physical health care within mental health services. Sydney: New South Wales Department of Health; 2009.

The Scottish Government. Mental health strategy for Scotland: 2012–2015. Edinburgh: The Scottish Government; 2012.

Welsh Assembly Government. The role of community mental health teams in delivering community mental health services: interim policy implementation guidance and standards. Welsh Assembly Government; 2010.

Royal College of Psychiatrists. Improving physical health for people with a mental illness: what can be done? Faculty Report FR/GAP/01. London: Royal College of Psychiatrists; 2013.

Canadian Mental Health Association. Recommendations for preventing and managing co-existing chronic physical conditions and mental illnesses. 2008. Available from http://ontario.cmha.ca/public_policy/recommendations-for-preventing-and-managing-co-existing-chronic-physical-conditions-and-mental-illnesses/#.VYsXXcYxHUI. Accessed 30 March 2016.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: treatment and management. NICE clinical guideline 178. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; 2014.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Bipolar disorder: the assessment and management of bipolar disorder in adults, children and young people in primary and secondary care. NICE clinical guideline 185. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; 2015.

Lewin Group Inc. and Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Approaches to integrating physical health services into behavioral health organizations: a guide to resources, promising practices and tools. Available from http://www.integration.samhsa.gov/Approaches_to_Integrating_Physical_Health_Services_into_BH_Organizations_RIC.pdf. 2012. Accessed 30 March 2016.

Schroeder S. What to do with a patient who smokes. J Am Med Assoc. 2005;294(4):482–7.

Schroeder S, Morris C. Confronting a neglected epidemic: tobacco cessation for persons with mental illnesses and substance abuse problems. Annu Rev Public Health. 2010;31:297–314.

Chwastiak L, Cruza-Guet MC, Carroll-Scott A, Sernyak M, Ickovics J. Preventive counseling for chronic disease: missed opportunities in a community mental health center. Psychosomatics. 2013;54(4):328–35. doi:10.1016/j.psym.2012.10.003.

Greening J. Physical health of patients in rehabilitation and recovery: a survey of case note records. Psychiatric Bulletin. 2005;29(6):210–2.

Himelhoch S, Leith J, Goldberg R, Kreyenbuhl J, Medoff D, Dixon L. Care and management of cardiovascular risk factors among individuals with schizophrenia and type 2 diabetes who smoke. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2009;31(1):30–2.

Anderson A, Bowman J, Knight J, Wye P, Terry M, Grimshaw S, et al. Smoking-related care provision within community mental health settings: a cross-sectional survey of Australian service managers. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(7):707–10.

Bartlem K, Bowman J, Freund M, Wye P, Lecathelinais C, McElwaine K, et al. Acceptability and receipt of preventive care for chronic-disease health risk behaviours reported by clients of community mental health services. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66(8):857–64.

Bartlem K, Bowman J, Freund M, Wye P, McElwaine K, Wolfenden L, et al. Care provision to prevent chronic disease by community based mental health clinicians. Am J Prevent Med. 2014;47(6):762–70.

Flodgren G, Parmelli E, Doumit G, Gattellari M, O'Brien M, Grimshaw J, et al. Local opinion leaders: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;8:CD000125. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000125.pub4.

Shojania K, Jennings A, Mayhew A, Ramsay C, Eccles M, Grimshaw J. The effects of on-screen, point of care computer reminders on processes and outcomes of care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;3:CD001096.

Arditi C, Rege-Walther M, Wyatt JC, Durieux P, Burnand B. Computer-generated reminders delivered on paper to healthcare professionals; effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12:CD001175. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001175.pub3.

Grimshaw J, Thomas R, MacLennan G, Fraser C, Ramsay C, Vale L, et al. Effectiveness and efficiency of guideline dissemination and implementation strategies. Health Technol Assess. 2004;8(6):1–72.

Forsetlund L, Bjorndal A, Rashidian A, Jamtvedt G, O'Brien M, Wolf F, et al. Continuing education meetings and workshops: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;2:CD003030.

Jamtvedt G, Young J, Kristofferson D, O'Brien M, Oxman A. Audit and feedback: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;2:CD000259.

Ivers N, Jamtvedt G, Flottorp S, Young JM, Odgaard-Jensen J, French SD, et al. Audit and feedback: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;6:CD000259. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000259.pub3.

Giguere A, Legare F, Grimshaw J, Turcotte S, Fiander M, Grudniewicz A, et al. Printed educational materials: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;10:CD004398. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004398.pub3.

O'Brien MA, Rogers S, Jamtvedt G, Oxman AD, Odgaard-Jensen J, Kristoffersen DT, et al. Educational outreach visits: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;4:CD000409. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000409.pub2.

Bakker M, Mullen P, de Vries H, van Breukelen G. Feasibility of implementation of a Dutch smoking cessation and relapse prevention protocol for pregnant women. Patient Educ Couns. 2003;49:35–43.

Moher M, Yudkin P, Wright L, Turner R, Fuller A, Schofield T, et al. Cluster randomised controlled trial to compare three methods of promoting secondary prevention of coronary heart disease in primary care. Br Med J. 2001;322:1–7.

Katz D, Brown R, Muehlenbruch D, Fiore M, Baker T. Implementing guidelines for smoking cessation: comparing the efforts of nurses and medical assistants. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27(5):411–6.

Papadakis S, McDonald P, Mullen K, Reid R, Skulsky K, Pipe A. Strategies to increase the delivery of smoking cessation treatments in primary care settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev Med. 2010;51:199–213.

Wolfenden L, Wiggers J, Knight J, Campbell E, Spigelman A, Kerridge R, et al. Increasing smoking cessation care in a preoperative clinic: a randomized controlled trial. Prev Med. 2005;41(1):284–90.

Freund M, Campbell E, Paul C, Sakrouge R, Lecathelinais C, Knight J, et al. Increasing hospital-wide delivery of smoking cessation care for nicotine-dependent inpatients: a multi-strategic intervention trial. Addiction. 2009;104(5):839–49.

Kaner E, Lock C, Heather N, McNamee P, Bond S. Promoting brief alcohol intervention by nurses in primary care: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2003;51:277–84.

McElwaine K, Freund M, Campbell E, Knight J, Bowman J, Wolfenden L, et al. Increasing preventive care by primary care nursing and allied health clinicians: a non-randomized, controlled trial. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(4):424–34.

Maki M, Bjorklund P. Improving cardiovascular disease screening in community mental health centers. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2013;49(3):179–86. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6163.2012.00348.x.

Hawkins N, Sanson-Fisher R, Shakeshaft A, D'Este C, Green L. The multiple baseline design for evaluating population-based research. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33(2):162–8.

Bartlem K, Bowman J, Freund M, Wye P, McElwaine K, Knight J, et al. Evaluating the effectiveness of a clinical practice change intervention in increasing clinician provision of preventive care in a network of community based mental health services: a study protocol of a non-randomised, multiple baseline trial. Implement Sci. 2013;8:85. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-8-85.

Revell C, Schroeder S. Simplicity matters: using system-level changes to encourage clinician intervention in helping tobacco users quit. Nicotine Tob Res. 2005;7(S1):S67–9.

Ministry of Health. New Zealand Smoking Cessation Guidelines. Wellington: Ministry of Health; 2007.

Ministerial Council on Drug Strategy. National Tobacco Strategy, 2004–2009: the strategy. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2004.

National Health and Medical Research Council. Australian guidelines to reduce health risks from drinking alcohol. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2009.

National Health and Medical Research Council. Dietary guidelines for Australian adults. Canberra: Commonwealth Department of Health and Ageing; 2003.

Department of Health and Aged Care. An active way to better health. Canberra: Australian Government; 1999.

Grimshaw J, Eccles M, Lavis J, Hill S, Squires J. Knowledge translation of research findings. Implement Sci. 2012;7(50):7–50.

Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO. The Fagerstrom test for nicotine dependence: a revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86(9):1119–27.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. National Nutrition Survey selected highlights Australia 1995. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics; 1997.

Babor T, Higgins-Biddle J, Saunders J, Monteiro M. AUDIT. The alcohol use disorders identification test: guidelines for use in primary care. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2001.

Marshall AL, Hunt J, Jenkins D. Knowledge of and preferred sources of assistance for physical activity in a sample of urban Indigenous Australians. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Activ. 2008;5:22. doi:10.1186/1479-5868-5-22.

McElwaine K, Freund M, Campbell E, Knight J, Bowman J, Doherty E, et al. The delivery of preventive care to clients of community health services. BioMed Central Health Serv Res. 2013;13:167.

Department of Health and Aged Care. Measuring remoteness: Accessibility/Remoteness Index of Australia (ARIA), Occasional Papers: New Series Number 14. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2001.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. SEIFA: socio-economic indexes for areas. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics; 2008.

Pagano M, Gauvreau K. Multiple comparisons procedures. Principles of biostatistics. Belmount: Duxbury; 2000.

Grol R, Wensing M, Eccles M. Improving patient care: the implementation of change in clinical practice. London: Elsevier; 2005.

Organ B, Nicholson E, Castle D. Implementing a physical health strategy in a mental health service. Australas Psychiatry. 2010;18(5):456–9.

Ehrlich C, Kendall E, Frey N, Denton M, Kisely S. Consensus building to improve the physical health of people with severe mental illness: a qualitative outcome mapping study. BioMed Central Health Serv Res. 2015;15:83. doi:10.1186/s12913-015-0744-0.

Michie S, Johnston M, Abraham C, Lawton R, Parker D, Walker A. Making psychological theory useful for implementing evidence based practice: a consensus approach. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005;14(1):26–33. doi:10.1136/qshc.2004.011155.

Vidrine J, Shete S, Cao Y, Greisinger A, Harmonson P, Sharp B, et al. Ask advise connect: a new approach to smoking treatment delivery in healthcare settings. JAMA. 2013;173(6):458–64.

Stead LF, Buitrago D, Preciado N, Sanchez G, Hartmann-Boyce J, Lancaster T. Physician advice for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;5:CD000165. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000165.pub4.

Aveyard P, Begh R, Parsons A, West R. Brief opportunistic smoking cessation interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis to compare advice to quit and offer of assistance. Addiction. 2012;107(6):1066–73. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03770.x.

Rose SA, Poynter PS, Anderson JW, Noar SM, Conigliaro J. Physician weight loss advice and patient weight loss behavior change: a literature review and meta-analysis of survey data. Int J Obes (Lond). 2013;37(1):118–28. doi:10.1038/ijo.2012.24.

Harris SK, Louis-Jacques J, Knight JR. Screening and brief intervention for alcohol and other abuse. Adolesc Med. 2014;25(1):126–56.

Stead L, Perera R, Lancaster T. Telephone counselling for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;3:CD002850.

Eakin E, Lawler S, Vandelanotte C, Owen N. Telephone interventions for physical activity and dietary behavior change: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(5):419–34.

Stead L, Perera R, Lancaster T. A systematic review of interventions for smokers who contact quitlines. Tob Control. 2007;16(S1):i3–8.

Ossip-Klein D, McIntosh S. Quitlines in North America: evidence base and applications. Am J Med Sci. 2003;326(4):201–5.

Newman V, Flatt S, Pierce J. Telephone counseling promotes dietary change in healthy adults: results of a pilot trial. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108(8):1350–4.

Robson D, Hadded M, Gray R, Gournay K. Mental health nursing and physical health care: a cross sectional study of nurses’ attitudes, practice and perceived training needs for the physical health care of people with severe mental illness. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2013;22(5):409–17.

Johnson J, Malchy L, Ratner P, Hossain S, Procyshyn R, Bottorff J, et al. Community mental healthcare providers’ attitudes and practices related to smoking cessation interventions for people living with severe mental illness. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;77(2):289–95.

Happell B, Platania-Phung C, Scott D. What determines whether nurses provide physical health care to consumers with serious mental illness? Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2014;28(2):87–93. doi:10.1016/j.apnu.2013.11.001.

Bartlem K, Bowman J, Ross K, Freund M, Wye P, McElwaine K et al. Mental health clinician attitudes to the provision of preventive care for chronic disease risk behaviours and association with care provision. BMC Psychiatry. Accepted for publication.

Lawrence C, Bluhm J, Foldes S, Alesci N, Klatt C, Center B, et al. A randomized trial of a pay-for-performance program targeting clinician referral to a state tobacco quitline. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(18):1993–9.

Krist A, Woolf S, Frazier C, Johnson R, Rothemich S, Wilson D, et al. An electronic linkage system for health behavior counseling: Effect on delivery of the 5A’s. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35(5S):S350–8.

Ward J, Sanson-Fisher R. Accuracy of patient recall of opportunistic smoking cessation advice in general practice. Tob Control. 1996;5(2):110–3.

Conroy M, Majchrzak N, Silverman C, Chang Y, Regan S, Schneider L, et al. Measuring provider adherence to tobacco treatment guidelines: a comparison of electronic medical record review, patient survey, and provider survey. Nicotine Tob Res. 2005;7(Supp1):S35–43.

Durlak JA, DuPre EP. Implementation matters: a review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. Am J Community Psychol. 2008;41(3–4):327–50. doi:10.1007/s10464-008-9165-0.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all members of the Preventive Care team, the CHIME team, the CATI interviewers and the community mental health service staff and clients for their contribution to the project. We would like to thank Christophe Lecathelinais for his statistical assistance throughout the project.

Funding

The study is funded with infrastructure support from the Hunter Medical Research Institute and Hunter New England Local Health District Population Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

All authors provided substantial contribution to the conception and design of the study and interpretation of the data. All authors provided substantial contribution to drafting and revising of the manuscript and gave final approval of the version to be published. Authors DB, PM and KB contributed to the analysis of the data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Bartlem, K.M., Bowman, J., Freund, M. et al. Effectiveness of an intervention in increasing the provision of preventive care by community mental health services: a non-randomized, multiple baseline implementation trial. Implementation Sci 11, 46 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-016-0408-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-016-0408-4