Abstract

Background

We recently reported that enhanced [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake in skeletal muscles predicts disease aggressiveness in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). The present experimental study aimed to assess whether this predictive potential reflects the link between FDG uptake and redox stress that has been previously reported in different tissues and disease models.

Methods

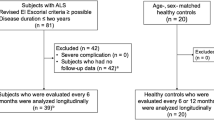

The study included 15 SOD1G93A mice (as experimental ALS model) and 15 wildtype mice (around 120 days old). Mice were submitted to micro-PET imaging. Enzymatic pathways and response to oxidative stress were evaluated in harvested quadriceps and hearts by biochemical, immunohistochemical, and immunofluorescence analysis. Colocalization between the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and the fluorescent FDG analog 2-[N-(7-nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazol-4-yl)amino]-2-deoxyglucose (2-NBDG) was performed in fresh skeletal muscle sections. Finally, mitochondrial ultrastructure and bioenergetics were evaluated in harvested quadriceps and hearts.

Results

FDG retention was significantly higher in hindlimb skeletal muscles of symptomatic SOD1G93A mice with respect to control ones. This difference was not explained by any acceleration in glucose degradation through glycolysis or cytosolic pentose phosphate pathway (PPP). Similarly, it was independent of inflammatory infiltration. Rather, the high FDG retention in SOD1G93A skeletal muscle was associated with an accelerated generation of reactive oxygen species. This redox stress selectively involved the ER and the local PPP triggered by hexose-6P-dehydrogenase. ER involvement was confirmed by the colocalization of the 2-NBDG with a vital ER tracker. The oxidative damage in transgenic skeletal muscle was associated with a severe impairment in the crosstalk between ER and mitochondria combined with alterations in mitochondrial ultrastructure and fusion/fission balance. The expected respiratory damage was confirmed by a deceleration in ATP synthesis and oxygen consumption rate. These same abnormalities were represented to a markedly lower degree in the myocardium, as a sample of non-voluntary striated muscle.

Conclusion

Skeletal muscle of SOD1G93A mice reproduces the increased FDG uptake observed in ALS patients. This finding reflects the selective activation of the ER-PPP in response to significant redox stress associated with alterations of mitochondrial ultrastructure, networking, and connection with the ER itself. This scenario is less severe in cardiomyocytes suggesting a relevant role for either communication with synaptic plaque or contraction dynamics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a neurodegenerative disease of upper and lower motor neurons leading to a severe impairment in the interplay between the nervous motor chain and the skeletal muscle, eventually resulting in progressive paralysis and death [1,2,3,4]. Although the underlying mechanisms remain uncertain, several studies suggested a relevant role for the imbalance between reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation and detoxification [5, 6] both in the central nervous system and skeletal muscles. Nevertheless, the absence of methods able to evaluate the redox stress and the antioxidant responses in vivo so far prevented to define the relevance of this alteration in ALS progression.

We previously reported a predictive power of spinal cord [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake computationally extracted from PET/CT images of ALS patients [7]. The apparent metabolic activation of this nervous district faced an opposite pattern in the brain cortex that showed a generalized reduction in tracer uptake [8]. By contrast, it extended to the psoas muscles of the same patients, suggesting a link between the metabolic pattern of the second motoneuron and its effector [9].

FDG uptake is commonly considered an index of glucose consumption. Nevertheless, several studies recently challenged this classical assumption and reported a direct and strict link between tracer retention and the activation of a specific pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) triggered by the “omnivore” enzyme hexose-6P-dehydrogenase (H6PD) within the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) of cancer cells [10, 11], neurons and astrocytes [12], cardiomyocytes [13] and, more importantly, in skeletal muscles [14]. A major function of PPP is the reduction of NADP+ to NADPH to fuel the glutathione-dependent antioxidant responses. Accordingly, the present study aimed to verify whether this kinetic model accounts for the capability of FDG uptake to track the redox mechanisms underlying ALS skeletal muscle damage, at least in SOD1G93A experimental model. This analysis was complemented with the evaluation of the myocardium, in order to verify whether the metabolic reprogramming selectively affects the motor chain or, rather, it reflects a systemic phenomenon involving all striated muscles regardless of their connection with the second motor neuron.

Material and methods

Animal models

All experiments were carried out in accordance with the guidelines established by the European Communities Council (Directive 114 2010/63/EU of September 22, 2010) and with Italian DL n.26/2014 and were approved by the local Ethical Committee and by the Italian Ministry of Health (Authorization No. 97/2017-PR). The study included thirty 118/127-day-old mice (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME, USA): 15 B6SJL-Tg (SOD1*G93A)1Gur mice expressing high copy number of mutant human SOD1 with a Gly93Ala substitution (SOD1G93A) and 15 background-matched B6SJL wildtype mice, considered as the “control group” [15]. All transgenic mice were bred in the animal facility of the Pharmacology and Toxicology Unit, Department of Pharmacy, University of Genoa (Italy), and identified by analyzing tissue extracts from tail tips, as previously described [16]. SOD1G93A mice were studied at a late phase of disease and synchronized by motor impairment determination, defined by our validated method [17]. Age-matched wildtype mice were used as controls. Both female and male mice were used in the experiments; sexes were balanced in each experimental group to avoid bias due to sex-related intrinsic differences. Animals were housed at constant temperature (22 ± 1 °C) and relative humidity (50%) with a regular 12-h light cycle (light 7 AM–7 PM). Food (type 4RF21 standard diet; Mucedola, Settimo Milanese, Italy) and water were freely available. All efforts were made to minimize animal suffering and to use only the number of animals necessary to produce reliable results. All mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation.

Experimental micro-PET imaging

Sample size of mice submitted to micro-PET imaging was defined based on the hypothesis of a 40% increase of skeletal muscle FDG uptake induced by ALS, coupled with an expected variation coefficient of tracer retention in this same tissue approaching 16%. These features were entered into a freely available calculator (http://www.rad.jhmi.edu/jeng/javarad/samplesize/#references) that estimated sample size to five mice per group as proposed by Eng et al. [18]. All animals were fasted for 6 h, weighted, and anesthetized with intra-peritoneal ketamine (100 mg/Kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg). Serum glucose level was tested and FDG (3–4 MBq) was injected through a tail vein. Forty minutes later, mice underwent a 10-min static acquisition in a dedicated micro-PET system (Albira, Bruker, USA) whose dual ring configuration allows the acquisition of the whole mouse body. After its completion, mice were immediately euthanized by cervical dislocation.

Ex vivo extraction fraction of FDG and glucose

Three mice per group were sacrificed; quadriceps and hearts were harvested to analyze ex vivo FDG uptake and glucose consumption. The quadriceps muscle side was randomly selected. Ex vivo FDG uptake of quadriceps and hearts was evaluated using the Ligand-Tracer White® instrument (Ridgeview, Uppsala, SE) according to our previously validated procedure [12, 14, 19]. Briefly, the device consists of a beta-emission detector and a rotating platform harboring a standard Petri dish. The rotation axis is inclined at 30° from the vertical, so that the organ alternates its position from the nadir (for incubation) to the zenith (for counting) every minute. Slices (300 μm thick) of quadriceps or hearts were stuck in the outer ring of a Petri dish with octyl-cyanoacrylate (Dermabond, Ethicon, US) and covered with 3 mL solution collected from an input vial containing 4 mL of Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) containing glucose and FDG at the concentration of 5.5 mM (1 g/L) and 2 MBq/mL, respectively. Time-activity curves were thus obtained by subtracting decay-corrected background counting rate from the corresponding target value, as previously described [12, 14, 19, 20]. After 40 min, an aliquot of 0.5 mL was sampled both from the input vial and from the Petri dish (output) to measure the radioactivity concentration using a dose calibrator with an activity resolution < 10 KBq (Capintec CRC55).

Fractional FDG uptake was thus calculated as:

where Ainput and Aoutput represent activity (MBq) in the surnatant before and after exposure to the muscle specimen, respectively.

After the measurement of FDG radioactivity concentration, the medium aliquots were appropriately stored for glucose assay. Glucose consumption was measured as:

where Cinput and Coutput represent the corresponding mM concentrations in the surnatant before and after exposure to the muscle specimen, respectively. Medium glucose concentration was assayed following the reduction of NADP, at 340 nm, using the following solutions: 100 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 2 mM MgCl2, 2 mM ATP, and 4 mg HK/G6PD (Sigma-Aldrich).

Sample preparation for biochemical analyses

Three dedicated quadriceps and three hearts of each group were homogenized with a Potter-Elvehjem in 1 mL of homogenization buffer (0.25 M sucrose, 0.15 M KCl, 1 mM EDTA, 10 Mm Tris-HCl pH 7.4). An aliquot of obtained homogenate was immediately frozen at − 80 °C while the remaining sample was immediately used for mitochondria isolation. Briefly, the homogenate was centrifuged at 800×g for 10 min to precipitate nuclei and cellular debris. The supernatant collected was centrifuged for 15 min at 12,000×g. The pellet obtained, containing mitochondria, was resuspended in a solution buffer (0.225 M sucrose, 0.075 M mannitol, 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 1 mM EDTA), centrifuged for 10 min at 1,000×g and washed by centrifugation at 12,000×g for 15 min [21]. Protein concentration was tested by Bradford analysis [22].

Oxygen consumption and ATP synthesis assay in isolated mitochondria

Oxygen consumption was measured in fresh mitochondria by means of an amperometric oxygen electrode (Microrespiration, Unisense A/S, Århus, Denmark) in a closed chamber (volume 1.7 ml) magnetically stirred, at room temperature. For each fresh sample, 25 μg of proteins were incubated in the respiration buffer composed of 120 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM KH2PO4, 50 mM Tris HCl, pH 7.4, and 25 μg/ml ampicillin. The following substrates were used: 5 mM pyruvate + 2.5 mM malate to stimulate complexes I-III-IV [23].

A luciferin/luciferase chemiluminescence method was used to measure ATP synthase in fresh mitochondria. For each sample, 25 μg of proteins were incubated for 10 min at 37 °C in a medium that contained: 10 mM Tris/HCl (pH 7.4), 100 mM KCl, 1 mM EGTA, 2.5 mM EDTA, 5 mM MgCl2, 5 mM KH2PO4, 0.6 mM Ouabain, and Ampicillin (25 μg/ml). The same substrates described for the oxymetric analysis were used. After 10 min of incubation, 0.1 mM ADP was added, to induce ATP synthesis, which was measured by means of a luminometer (Glomax 20/20 Luminometer, Promega Italia, Milano, Italy). ATP standard solutions in the concentration range 10−9–10−5 M were used for calibration [24].

Enzymatic assay

Enzymatic assays were performed using frozen homogenates of three quadriceps and three hearts of each group. Enzymatic assays were performed in a double beam spectrophotometer (UNICAM UV2, Analytical S.n.c., Italy) [10,11,12,13,14].

Hexokinase (HK), hexose-6-phostate dehydrogenase (H6PD), and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) activities were assayed following reduction of NADP, at 340 nm. Phosphofructokinase (PFK) activity was assayed following oxidation of NADH, at 340 nm.

The following assays solutions were used: HK: Tris-HCl-pH 7.4-100 mM (TRIS7.4), MgCl2 2 mM, glucose 200 mM, ATP 1 mM, NADP 0.5 mM, and 2 UI G6PD (Sigma-Aldrich); H6PD: TRIS7.4, 2DG6P 10 mM, NADP 0.5 mM; G6PD: TRIS7.4, G6P 10 mM, and NADP 0.5 mM; and PFK: Tris-HCl pH 8 100 mM, MgCl2 2 mM, KCl 5 mM, fructose-6-phosphate 2 mM, ATP 1 mM, phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) 0.5 mM, NADH 0.2 mM, and 2 IU pyruvate kinase (PK)/4 IU lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) (Sigma-Aldrich).

Glutathione reductase (GR) activity and NADPH/NADP ratio were evaluated spectrophotometrically, at 405 and 450 nm, respectively, using GR Assay Kit (Abcam: ab83461) and NADP-NADPH Assay Kit (Abcam: ab65349), following the manufacturer’s instructions.

To assess lipid peroxidation, malondialdehyde (MDA) levels were evaluated, by the thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) assay, with minor modifications [13, 25]. The activity assay of the complex I was measured on 50 μg of total protein as previously described [10, 12, 26].

Western blot analysis

Western blot (WB) experiments were performed according to the standard procedure. Frozen homogenates were prepared from the quadriceps of three mice per group and were sonicated twice for 10 s in ice, with a break of 30 s. Denaturing electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) was performed using Mini PROTEAN TGX Precast gels (Bio Rad). For each sample, 25 μg of total protein were loaded. Run was performed at 4 °C, at 70 mA for each gel, for 30–40 min. Running buffer contained 0.05 M Tris (pH 8.0), 0.4 M glycine, 1.8 mM EDTA, and 0.1% SDS. Electrophoretically separated samples were transferred onto nitrocellulose (NC) membranes by electroblotting, at 400 mA for 1 h in Tris-glycine buffer (50 mM Tris and 380 mM glycine) plus 20% (v/v) methanol, at 4 °C. NC membranes were incubated with the specific antibodies diluted in Tris Buffer Saline + 0.15% tween (TBST). We tested the following antibodies: anti-mitofusin 2 (Mfn2, ThermoFisher: PA5 72811, 1:1000), anti-dynamin-1-like protein (Drp1, ThermoFisher: PA5 34768, 1:2000), anti-calnexin (ThermoFisher: MA3-027, 1:500), and anti-GAPDH (Cell Signaling: #5174, 1:1000). After extensive washing with 0.15% TBST, 1 h of incubation with secondary horseradish peroxidase-conjugated Abs diluted in TBST (1:10,000 for anti-mouse and anti-rabbit antibodies) was performed.

Bioimaging by confocal microscopy

The experiments were performed on dedicated fresh skeletal muscle sections from three SOD1G93A and three control mice, promptly after excision. The sections were gently stretched to reduce thickness without affecting the viability of tissue cells (verified by exclusion of the non-permeable dye DAPI in parallel samples) and immediately incubated at 37 °C for 10 min with the fluorescent probes 2-[N-(7-nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazol-4-yl)amino]-2-deoxyglucose (2-NBDG) (50 μM ) and ER-TrackerTM Red (1 μM), both from Molecular Probes (InVitrogen, Eugene, OR). Nuclei were stained with the cell-permeable dye Hoechst 33342 (10 μM). Images were obtained using the SP2-AOBS confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems, Mannheim, Germany).

Immunofluorescence and immunohistochemical analysis

Soon after sacrifice, 3 half-hearts and 3 quadriceps were harvested from controls and from SOD1G93A mice, embedded in OCT and snap-frozen in precooled isopentane. Six-micrometer-thick serial cryostat sections were obtained.

For the immunofluorescence analysis, immediately after cutting, the sections were fixed for 10 min in cold acetone, followed by incubation with MitoTracker® Red (Molecular Probes), at 10 nM for 20 min at 37 °C. For reactive oxygen species (ROS) staining, serial sections from the same samples were fixed for 10 min in acetone, followed by incubation with 10 μM 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (H2DCFDA; Molecular Probes) for 30 min and a wash in PBS.

For immunohistochemical staining of skeletal muscles infiltrated macrophages the following antibodies were used: rat anti-mouse CD206 (AbD Serotec, 1:200, 5 μg/ml) to detect macrophages M2, rat anti-mouse CD86 clone PO.3 (Millipore, 1:100, 5 μg/ml) to detect macrophages M1, and rat anti-mouse CD11b (Novus Biologicals, 1:200, 5 μg/ml).

Ultrastructural analysis

Three quadriceps and three hearts per group were dissected and fixed in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer containing 2.5% glutaraldehyde (Electron Microscopy Science, Hatfield, PA, USA), for 2 h at room temperature. Samples were postfixed in osmium tetroxide for 2 h and 1% uranyl acetate for 2 h. Samples were next dehydrated through a graded ethanol series and propylene oxide and embedded in epoxy resin (Poly-Bed; Polysciences, Inc., Warrington, PA, USA) overnight at 42 °C and 2 days at 60 °C. Ultrathin sections (50 nm) were counterstained with 5% uranyl acetate and lead citrate and observed with transmission electron microscope (TEM) HT7880, Hitachi, Japan.

Image analysis

Micro-PET images were reconstructed using a maximum-likelihood expectation-maximization (MLEM) algorithm and were qualitatively inspected. Images were analyzed using the routine of a commercial software (PMOD, Zurich, CH). Two nuclear medicine physicians, unaware of model nature (transgenic or wildtype), drew volumes of interest (VOIs) on the left and right hindlimb skeletal muscles and on the metabolically active left ventricular myocardium to measure the mean standardized uptake value (SUV) according to the formula:

where [FDG] indicates average FDG concentration in kBq/ml within any given VOI and bodyweight is expressed in kilograms and injected activity in MBq. Skeletal muscle and myocardial FDG concentration were divided by the corresponding value in the blood pool to obtain the SUV ratio (SUVr). For WB analysis, the signal was acquired with Alliance 6.7 WL 20 M (UVITEC, Cambridge, UK), and UV1D software (UVITEC). Densitometry analysis was performed using the dedicated routine of ImageJ software (ImageJ Version 2.0.0-rc-65/1.51 s). For colocalization analysis, six randomly selected fields were analyzed in three independent samples harvested from either SOD1G93A and control mice. Original unadjusted and uncorrected images were processed using ImageJ software for the evaluation of colocalization, which was expressed as the percentage of above-background pixels in 2-NBDG images that overlapped above-background pixels in ER images, with background threshold set by the Costes’ method [27].

For immunofluorescence analysis, images were acquired by the Fluoview FV500 software and the fluorescence was quantified using the same ImageJ software. Immunohistochemical images were acquired with Leica DM RX microscopy and were analyzed using Scion Image software [28].

Finally, for ultrastructural analysis, digital images were acquired with Megaview 3 camera (EMSIS GmbH, Germany).

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Two-tailed Student t test for unpaired data was used. Levene’s test for equality of variances was used to test the homogeneity of variances of the two groups. When homogeneity was not satisfied, the Welch-Satterthwaite method was used to adjust the p value for this assumption violation. Statistical significance was considered for p < 0.05. In all analyses, p value was complemented by the evaluation of standardized difference between the two means estimated by Cohen’s d index. A complete description of these evaluations is reported in Supplementary Table 1. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software 26.0 (Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

SOD1G93A mutation and FDG uptake in skeletal muscle

At the time of micro-PET imaging (around 120 days after birth), body weight was significantly lower in SOD1G93A mice compared to controls (Fig. 1a) while no differences were observed in serum glucose levels between the two groups (Fig. 1b). Hindlimb SUVr was significantly higher in SOD1G93A mice with respect to controls (0.43 ± 0.04 vs. 0.31 ± 0.07 in SOD1G93A and control groups, respectively, p = 0.014, Fig. 1c, d). This difference also applied to rough SUV data (0.44 ± 0.09 vs. 0.33 ± 0.03 in mutated and control mice, respectively, p = 0.042, Supplementary Table 2).

In vivo and ex vivo effects of SOD1G93A mutation in skeletal muscle. a, b Bodyweight and serum glucose levels in controls (green column) and SOD1G93A mice (red column). c Average of FDG retention expressed as standardized uptake value ratio (SUVr) in control (green column) and SOD1G93A skeletal muscle (red column). d Representative hindlimb SUV of control and SOD1G93A mice. e Average time-course of “ex-vivo” radioactivity expressed as a fraction of the FDG dose measured by the Ligand-Tracer White® device, in quadriceps harvested from control (green line) and SOD1G93A mouse (red line). f Ex vivo glucose consumption of harvested quadriceps from control (green column) and SOD1G93A mouse (red column). Data are expressed as mean ± SD; a–dn = 5 for each group; e, fn = 3 for each group. Student t test for unpaired data was used for statistical evaluation

This finding was reproduced ex vivo, since FDG accumulation was higher in quadriceps harvested from SOD1G93A mice compared to the corresponding muscles harvested from wildtype littermates (Fig. 1e). In agreement with our hypothesis, the increase in tracer uptake was not paralleled by any difference in glucose extraction that was similar in control and SOD1G93A quadriceps (Fig. 1f).

Inflammatory markers

The increased tracer uptake of skeletal muscles was not fully explained by inflammatory infiltrates. Indeed, immunohistochemical analysis showed that CD86+ positive cells, responsible for the high tracer retention in inflammation, were scarcely represented and superimposable in both controls and SOD1G93A skeletal muscle (Fig. 2a, b). By contrast, CD11b+ and CD206+ positive cells were more represented in SOD1G93A quadriceps (Fig. 2c and d, and e and f, respectively). However, the prevalence of both CD11b+ and CD206+ was too low (< 4% of the imaged field) to justify the increased FDG accumulation in transgenic skeletal muscle.

Effect of SOD1G93A in quadriceps inflammatory infiltration. a, c, e Immunohistochemical representative images of CD86, CD11b, and CD206 expression, in controls (green edge line) and SOD1G93A (red edge line) quadriceps. b, d, f Quantitative representation of the CD86+, CD11b+, and CD206+ signal, expressed as a percent of the image field occupied by the specific cell staining. Data are expressed as mean ± SD, n samples = 3 for each group. Student t test for unpaired data was used for statistical evaluation

The activity of rate-limiting enzymes of glucose degradation in skeletal muscle of SOD1G93A mice

The effect of SOD1G93A mutation on FDG uptake in skeletal muscle was not explained by the response of enzymes regulating cytosolic glucose catabolism. Indeed, HK catalytic function was not affected by SOD1G93A mutation (Fig. 3a), while PFK activity was significantly reduced in transgenic muscles (Fig. 3b). An analogous consideration also applies to the cytosolic PPP, since G6PD catalytic function was superimposable in SOD1G93A and control littermates (Fig. 3c). By contrast, the enhanced tracer uptake matched the behavior of H6PD, whose catalytic function was significantly increased in SOD1G93A skeletal muscle with respect to controls (Fig. 3d).

Effect of SOD1G93A mutation on enzymatic pathway and colocalization of 2-NBDG and ER signals in harvested quadriceps. a–d Respective activities of HK, PFK, G6PD, and H6PD in control (green column) and SOD1G93A groups (red column) of quadriceps homogenate. e Immunofluorescence representative images of ER (red fluorescence), 2-NBDG (green fluorescence), and colocalization staining signals (% of 2-NBDG voxels within the ER staining—white) in control and SOD1G93A quadriceps. Blue color reports the Hoechst 33342 signal. f, g Percent voxels over threshold of ER and 2-NBDG, respectively, in control and SOD1G93A quadriceps. h Percent of ER voxels within 2-NBDG staining. i Percent of 2-NBDG voxels within ER staining. Data are expressed as mean ± SD, n = 3 for each group. Student t test for unpaired data was used for statistical evaluation

Colocalization of 2-NBDG and ER signals in harvested quadriceps

The agreement between FDG uptake and H6PD activity suggested the activation of ER PPP in SOD1G93A skeletal muscles. This hypothesis was confirmed by confocal microscopy: ER signal intensity was similar in muscle samples obtained from either group (Fig. 3e, f). By contrast and in agreement with the analysis of FDG retention, 2-NBDG fluorescence was significantly higher in SOD1G93A quadriceps than in their wildtype littermates (Fig. 3e, g). At colocalization analysis, the fraction of ER voxels (volumetric picture elements) containing 2-NBDG was similar in both control and mutated skeletal muscle (Fig. 3e, h). However, the percentage of 2-NBDG voxels included within the ER was significantly higher in transgenic mice (Fig. 3e, i) indicating that SOD1G93A mutation increases the mobilization of this glucose analog from the cytosol to the ER.

Antioxidant response and oxidative stress

Altogether, obtained data suggest an acceleration of ER PPP, which should be associated with an increment of the NADPH production. Conversely, NADPH appeared significantly lower in transgenic quadriceps with respect to their wildtype littermates (Fig. 4a), despite a superimposable content of cofactor equivalents (NADP and NADPH) (Fig. 4b). However, this apparent discrepancy was explained by the higher GR activity in SOD1G93A quadriceps with respect to controls (Fig. 4c), since this enzyme uses NADPH as a cofactor.

Antioxidant response and oxidative stress in SOD1G93A mutation. a, b NADPH levels and total NADP+NADPH content in control (green column) and SOD1G93A (red column) quadricep homogenates represented as percent of control. c GR activity and d MDA content in control (green column) and SOD1G93A (red column) quadriceps. e Mean fluorescence index (MFI) of H2DCFDA in control and SOD1G93A quadriceps muscles. f Immunofluorescence representative images of MitoTracker® (as specific mitochondria staining—red fluorescence), H2DCFDA (as specific ROS staining—green fluorescence), and colocalization staining signals, in control and SOD1G93A quadriceps. Data are expressed as mean ± SD, n = 3 for each group. Student t test for unpaired data was used for statistical evaluation

Despite the increment of the enzymatic activities involved in the antioxidant defenses, SOD1G93A mutation was associated with a significant increment of lipid peroxidation and ROS level in SOD1G93A skeletal muscle in comparison to the wildtype littermates, as shown by the combined increase in MDA levels (Fig. 4d) and H2DCFDA-associated fluorescence (Fig. 4f). Intriguingly, H2DCFDA fluorescence was also found in sample regions devoid of MitoTracker® signal, suggesting a contribution of mitochondria with impaired membrane polarization to ROS generation.

Mitochondrial ultrastructure and bioenergetic evaluation in skeletal muscle

In the control group, normal mitochondria with well-defined cristae and membrane structure were seen in sub-sarcolemma and intermyofibrillar regions (Fig. 5a). By contrast, SOD1G93A quadriceps showed an evident alteration of mitochondrial inner cristae, suggesting an enhanced oxidative stress. In addition, transgenic skeletal muscles showed abnormal mitochondrial networking coupled with a severe impairment in their shape (Fig. 5b) as well as with a profound disruption in the mitochondrion-ER connection.

Mitochondrial/ER ultrastructure and bioenergetics activity in skeletal muscles. a, b Electron microscopy representative images of control and SOD1G93A quadriceps (n = 3). In both panels, red arrows show mitochondria while yellow arrows show ER ultrastructural profiles. c–e Western blot analysis and relative densitometry quantitative analyses of Mfn2, Drp1, and Calnexin in the two groups. f, g ATP synthesis and oxygen consumption rate stimulated by pyruvate/malate in control (green column) and SOD1G93A (red column) of isolated mitochondria. h Complex I activity in isolated mitochondria form control (green column) and SOD1G93A muscles (red column) studied by the FeCN reduction in the presence of NADH. Data are expressed as mean ± SD, n = 3 for each group. Student t test for unpaired data was used for statistical evaluation

Consequently, we evaluated the main regulator of the mitochondrial fusion/fission machinery, by western blot analysis: Mfn2, a mitochondria-associated membrane (MAM) protein that promotes mitochondrial fusion, and Drp1, a GTPase involved in mitochondrial fission. SOD1G93A skeletal muscle showed a significant decrease in Mfn2 protein amount (Fig. 5c) opposite to the increase of Drp1content with respect to control (Fig. 5d). Despite a significant alteration in mitochondrial fusion/fission, calnexin abundance did not change under SOD1G93A mutation (Fig. 5e).

These observations matched the functional alterations observed in quadriceps mitochondria. Indeed, ATP synthesis was significantly lower in mutated isolated mitochondria of SOD1G93A muscles with respect to control ones (Fig. 5f). This effect agreed with the reduction in oxygen consumption rate through complexes I-III-IV triggered by pyruvate-malate (Fig. 5g). Nevertheless, this response disagreed with the selective enhancement of complex I activity that was observed in mutated muscles when studied by the FeCN reduction in the presence of NADH (Fig. 5h) that, in turn, justifies the increase in ROS production.

Evaluation of glucose metabolism and redox status in the myocardium

Since the myocardium is a striated involuntary muscle independent of cholinergic neuromuscular synapses, we here investigated, for the first time, whether its function can be affected by the SOD1G93A mutation.

In vivo experiments did not show any differences in myocardium SUV and SUVr between control and mutated mice (Suppl Table 2 and Fig. 6a, respectively). Similarly, ex vivo SOD1G93A myocardium FDG kinetics accumulation was superimposable with respect to control littermates (Fig. 6b).

Evaluation of glucose metabolism and redox status in the cardiac myocardium of SOD1G93A and control mice. a Average of FDG retention expressed as standardized uptake value ratio (SUVr) in control (green column) and SOD1G93A myocardium (red column). Data are expressed as mean ± SD, n = 5 for each group. b Average time-course of “ex-vivo” radioactivity expressed as a fraction of the FDG dose, measured by the Ligand-Tracer White® apparatus, in myocardium harvested from control (green line) and SOD1G93A mice (red line). c–f Myocardial catalytic activities of HK, PFK, G6PD, H6PD, and GR (g) in control (green column) and SOD1G93A (red column). h MDA levels and i MFI H2DCFDA in control and SOD1G93A experimental groups. j, k Immunofluorescence representative images of Mitotracker® (as specific mitochondria staining—red fluorescence), H2DCFDA (as specific ROS staining—green fluorescence), and colocalization staining signals, in control and SOD1G93A myocardium. Data are expressed as mean ± SD, n = 3 for each group. Student t test for unpaired data was used for statistical evaluation

The catalytic function of the main enzymes involved in cytosolic glucose catabolism (HK, PFK, and G6PD) was similar between control and mutated myocardium (Fig. 6c–e). Moreover, SOD1G93A did not affect the activity of the reticular enzyme H6PD (Fig. 6f). In agreement with these data, the antioxidant response evaluated by GR catalytic function was not affected by SOD1G93A mutation (Fig. 6g) as well as the indexes of oxidative stress evaluating by MDA levels (Fig. 6h) and H2DCFDA-associated fluorescence (Fig. 6j). Finally, the relatively less evident damage with respect to skeletal muscle was confirmed by the virtual absence of inflammatory infiltrates in myocardial specimens.

Inflammatory infiltrates, mitochondrial function, and ultrastructure in the myocardium

Effect of SOD1G93A mutation on inflammatory infiltrates was less evident in the myocardium with respect to skeletal muscle. Indeed at immunohistochemical analysis, CD86+ and CD11b+ cells were virtually not represented in both groups (Suppl Figure 1, Panels A-D). On the other hand, evidence of CD206+ was similar in control and SOD1G93A (Suppl Figure 1, E-F).

Ultrastructural analysis confirmed the relatively lower involvement of the heart. With respect to skeletal muscle, mitochondria of mutated myocardium showed relatively less evident alterations in shape and in number of cristae that appeared disorganized and relatively less represented (Fig. 7a, b) in transgenic hearts. In agreement with the lower degree of ultrastructural impairment, isolated mitochondria from SOD1G93A myocardium showed a slight, but not significant, decrease in ATP synthesis associated with a significant reduction in OCR without any alteration in complex I activity (Fig. 7c–e).

Mitochondrial ultrastructure and bioenergetics activity in cardiac myocardium of SOD1G93A and control mice. a, b Electron microscopy representative images of control SOD1G93A myocardium. c, d ATP synthesis and oxygen consumption rate stimulated by pyruvate/malate in control (green column) and SOD1G93A (red column) of isolated mitochondria. e Complex I activity in isolated mitochondria of control (green column) and of mutated muscles (red column) studied by the FeCN reduction in the presence of NADH. Data are expressed as mean ± SD, n = 3 for each group. Student t test for unpaired data was used for statistical evaluation

Discussion

The present study confirms that the increased skeletal muscle FDG uptake observed in ALS patients also occurs in the SOD1G93A experimental model [9]. The increase in FDG accumulation rate was observed in living mice, under fasting conditions and in the presence of normal glucose levels. It was not caused by a physical activity, because mice were under anesthesia during the tracer distribution time. Moreover, it persisted ex vivo, under the incubation in a medium devoid of both hormonal signals and competing metabolites. The enhanced tracer avidity of skeletal muscles of transgenic SOD1G93A mice was not explained by inflammation. Indeed, the most FDG-avid inflammatory cells, CD86+ macrophages [29,30,31,32,33], were scarcely represented in SOD1G93A quadriceps muscle with a similar abundance with respect to control mice. Actually, CD11b+ and CD206+ cells were significantly more abundant in SOD1G93A quadriceps. However, they were only barely represented both in control and SOD1G93A quadriceps; thus, this difference was too low to account for the evident and diffuse increase of FDG uptake observed in mutated mice [34,35,36]. Finally, the high tracer avidity of SOD1G93A muscles also extended to the FDG analog 2-NBDG, whose fluorescence was diffusely increased in all myocytes. Thus, the present findings indicate that the increased FDG uptake reflects a metabolic shift of skeletal muscles.

Classical models consider an increased FDG uptake as the sign of an accelerated glucose consumption. Accordingly, our findings apparently disagree with recent evidence reporting a significant role of impaired glucose metabolism in ALS disease progression. Indeed, glycolytic flux had been found to be impaired in both the spinal cord [37] and gastrocnemius muscles [38] of different ALS experimental models while interventions able to increase glucose utilization [39, 40] were proven to provide a therapeutic benefit on disease progression. Similarly, the increased FDG retention conflicts with the response of PFK and G6PD activity, induced by SOD1G93A mutation, that would rather suggest a deceleration in glycolytic flux combined with a constant rate of cytosolic PPP. However, the divergent response of tracer retention and glycolytic flux to SOD1G93A mutation closely agrees with a series of previous observations [10,11,12,13,14] documenting a relative independence between FDG uptake and glucose consumption. According to this evidence, tracer accumulation rate largely reflects the activation of H6PD catalytic function within the ER as also confirmed by the selective localization of the FDG fluorescent analog, 2-NBDG, within the ER of transgenic muscles.

H6PD is the acknowledged trigger of the first two PPP reactions within the ER [41]. As for its cytosolic counterpart, the main role of this reticular pathway is the NADP+ reduction to NADPH to fuel both bio-reductive syntheses [42] and glutathione-dependent antioxidant responses [43]. In the present study, SOD1G93A quadriceps showed increased levels of both lipid peroxidation and ROS production, as suggested by the high levels of MDA and H2DCFDA-associated fluorescence coupled with the enhanced GR activity and the decreased NADPH/NADP ratio. On the other hand, the present data also indicate that the antioxidant response was not sufficient to counterbalance the oxidative stress production, as demonstrated by the lipid peroxidation accumulation in the SOD1G93A muscle. More interestingly, the evident response of H6PD, coupled with the relative invariance of G6PD catalytic function, configures the ER as a selective target of redox stress in transgenic muscles.

The high vulnerability of the ER to oxidative damage agrees with the strictly functional and physical connection of this organelle with the mitochondria whose electron transport chain is recognized as the main cellular ROS source [44,45,46,47]. Similarly, it matches the double target and contributor role attributed to the same ER in cell redox control [48], with glucose metabolism involved in all the three canonical branches of unfolded protein response, namely the inositol-requiring kinase 1 (IRE1) [49], protein kinase R-like ER kinase (PERK) [50], and activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6) [51] pathways.

In agreement with these assumptions and confirming the evidence in the literature for both patients and mouse experimental models [52,53,54], TEM showed a dramatic alteration in mitochondrial networking, coupled with a severe impairment in their shape and further associated with the loss of cristae in transgenic mice. This ultrastructural evidence confirms previous studies in ALS reporting a profound disruption in the mitochondrion-ER relationship [55], and thus in the main regulator of the fission/fusion machinery, used by all post-mitotic tissues, including skeletal muscle, to adapt mitochondrial morphology and function to cell bioenergetic requirements [56, 57]. This dynamic balance of mitochondrial location, size, and number is regulated by a series of GTPases; among these, Mfn2 promotes mitochondrial fusion as opposed to Drp1 that instead favors mitochondrial fission. The relevance of this equilibrium has been recently recognized by Tezze et al., who reported a significant reduction of fusion and fission proteins in atrophic muscles of elderly sedentary people [58]. Similarly, Drp1 protein level has been found to decrease during aging in cardiac and skeletal muscles of normal mice [59]. In the present study, the SOD1G93A mutation was associated with significantly decreased levels of Mfn2, facing an increased abundance of its opponent Drp1. Accordingly, the present data indicate that the muscular damage, associated with the SOD1G93A mutation, recognizes different mechanisms with respect to the aging process [60], although the present data do not permit to elucidate whether this consideration also extends to ALS patients.

The profound disruption of mitochondrial morphology and dynamics nicely agrees with the impairment in oxygen consumption rate and ATP synthesis that was observed in transgenic mice in agreement with previous literature [61,62,63]. However, despite a reduction of oxidative phosphorylation metabolism, the activity of complex I was higher in SOD1G93A muscle in comparison to the control sample, in agreement with previous observations [64]. This increment can explain the increase of ROS production, despite the reduction of aerobic activity, since complex I is considered the main oxidative stress producer of the electron transport chain [65]. Moreover, the maintenance of complex I activity suggests that the impairment of oxidative phosphorylation activity is principally associated with the loss of cristae organization and mitochondrial morphology and dynamics.

Finally, the simultaneous evaluation of the heart documented a markedly less evident alteration in cardiomyocytes of transgenic mice in all evaluated immune-histochemical, functional, and ultrastructural indexes. To the best of our knowledge, this evaluation is the first attempt to compare myocardial and skeletal muscle response to experimental ALS. The evidence of a cardiomyocyte impairment, though less severe or slower in its progression with respect to skeletal muscle, fits with previous studies documenting a relatively high incidence of left ventricular dysfunction in patients with long-lasting motor neuron disease [66]. It also agrees with previous evidence about a wide distribution of TDP-43 aggregates in post-mortem specimens of skeletal and cardiac muscle in ALS patients [67].

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study documents that the increased FDG uptake observed in ALS patients is reproduced in SOD1G93A mice and is not associated with any shift in cytosolic glucose metabolism. Rather, it reflects the selective activation of the ER-PPP triggered by the omnivore enzyme H6PD in response to a significant redox stress at least partially caused by an alteration of mitochondrial structure, networking, and connection with the ER itself. This series of events selectively involves skeletal muscles and is markedly less severe in cardiomyocytes suggesting a relevant role of either communication with a synaptic plaque or contraction dynamics. The present data may justify further research to identify methods interrogating the ER response to redox damage as a tool able to discover the earliest subclinical signs of this lethal neurodegenerative disease and possibly a new useful and non-invasive prognostic marker for ALS.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ALS:

-

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- SUV:

-

Average standardized uptake value

- FDG:

-

[18F]-Fluorodeoxyglucose

- ROS:

-

Reactive oxygen species

- PPP:

-

Pentose phosphate pathway

- G6PD:

-

Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase

- H6PD:

-

Hexose-6P-dehydrogenase

- ER:

-

Endoplasmic reticulum

- PFK:

-

Phosphofructokinase

- GR:

-

Glutathione reductase

- MDA:

-

Malondialdehyde

- HK:

-

Hexokinase

- 2-NBDG:

-

2-[N-(7-Nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazol-4-yl)amino]-2-deoxyglucose

- H2DCFDA:

-

2′,7′-Dichlorofluorescein diacetate

- Mfn2:

-

Mitofusin 2

- Drp1:

-

Dynamin-1-like protein

References

Hardiman O, Al-Chalabi A, Chio A. M Corr E, Logroscino G, Robberecht W, et al. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17085. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2017.71.

Wijesekera LC, Leigh PN. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2009;4:3. https://doi.org/10.1186/1750-1172-4-3.

Rowland LP, Shneider NA. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(22):1688–700. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM200105313442207.

Loeffler JP, Picchiarelli G, Dupuis L. Gonzalez De Aguilar JL. The role of skeletal muscle in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain Pathol. 2016;26(2):227–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/bpa.12350.

Bowling AC, Beal MF. Bioenergetic and oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases. Life Sci. 1995;56(14):1151–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/0024-3205(95)00055-b.

Singh A, Kukreti R, Saso L, Kukreti S. Oxidative stress: a key modulator in neurodegenerative diseases. Molecules. 2019;24(8):1583. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24081583.

Marini C, Cistaro A, Campi C, Calvo A, Caponnetto C, Nobili FM, et al. A PET/CT approach to spinal cord metabolism in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2016;43(11):2061–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-016-3440-3.

Marini C, Morbelli S, Cistaro A, Campi C, Caponnetto C, Bauckneht M, et al. Interplay between spinal cord and cerebral cortex metabolism in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain. 2018;141(8):2272–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awy152.

Bauckneht M, Lai R, Miceli A, Schenone D, Cossu V, Donegani ID, et al. Spinal cord hypermetabolism extends to skeletal muscle in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a computational approach to FDG PET/CT images. EJNMMI Res. 2020;10(1):23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13550-020-0607-5.

Marini C, Ravera S, Buschiazzo A, Bianchi G, Orengo AM, Bruno S, et al. Discovery of a novel glucose metabolism in cancer: the role of endoplasmic reticulum beyond glycolysis and pentose phosphate shunt. Sci Rep. 2016;6:25092. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep25092.

Cossu V, Bauckneht M, Bruno S, Orengo AM, Emionite L, Balza E, et al. The elusive link between cancer FDG uptake and glycolytic flux explain the preserved diagnostic accuracy of PET/CT in diabetes. Transl Oncol. 2020;13(5):100752. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranon.2020.100752.

Cossu V, Marini C, Piccioli P, Rocchi A, Bruno S, Orengo AM, et al. Obligatory role of endoplasmic reticulum in brain FDG uptake. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2019;46(5):1184–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-018-4254-2.

Bauckneht M, Pastorino F, Castellani P, Cossu V, Orengo AM, Piccioli P, et al. Increased myocardial 18F-FDG uptake as a marker of Doxorubicin-induced oxidative stress. J Nucl Cardiol. 2019. doi:10.1007/s12350-019-01618-x. Online ahead of print. .

Bauckneht M, Cossu V, Castellani P, Piccioli P, Orengo AM, Emionite L, et al. FDG uptake tracks the oxidative damage in diabetic skeletal muscle: an experimental study. Mol Metab. 2020;31:98–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molmet.2019.11.007.

Gurney ME, Pu H, Chiu AY, Dal Canto MC, Polchow CY, Alexander DD, Caliendo J, Hentati A, KwonYW, Deng HX, Chen W, Zhai P, Sufit RL, Siddique T. Motor neuron degeneration in mice that express a human Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase mutation. Science. 1994;264(5166):1772–1775. doi:https://doi.org/10.1126/science.8209258.

Bonifacino T, Cattaneo L, Gallia E, Puliti A, Melone M, Provenzano F, et al. In-vivo effects of knocking-down metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 in the SOD1G93A mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neuropharmacology. 2017;123:433–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2017.06.020.

Milanese M, Giribaldi F, Melone M, Bonifacino T, Musante I, Carminati E, et al. Knocking down metabotropic glutamate receptor 1 improves survival and disease progression in the SOD1(G93A) mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurobiol Dis. 2014;64:48–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbd.2013.11.006.

Eng J. Sample size estimation: how many individuals should be studied? Radiology. 2003;227(2):309–13. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2272012051.

Buschiazzo A, Cossu V, Bauckneht M, Orengo AM, Piccioli P, Emionite L, et al. Effect of starvation on brain glucose metabolism and 18F-2-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose uptake: an experimental in-vivo and ex-vivo study. EJNMMI Res. 2018;8(1):44. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13550-018-0398-0.

Scussolini M, Bauckneht M, Cossu V, Bruno S, Orengo AM, Piccioli P, et al. G6Pase location in the endoplasmic reticulum: Implications on compartmental analysis of FDG uptake in cancer cells. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):2794. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-38973-1.

Lescuyer P, Strub J-M, Luche S, Diemer H, Martinez P, Van Dorsselaer A, Lunardi J, Rabilloud T. Progress in the definition of a reference human mitochondrial proteome. Proteomics. 2003;3(2):157–67. https://doi.org/10.1002/pmic.200390024.

Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–54. https://doi.org/10.1006/abio.1976.9999.

Ravera S, Vaccaro D, Cuccarolo P, Columbaro M, Capanni C, Bartolucci M, et al. Mitochondrial respiratory chain Complex I defects in Fanconi anemia complementation group A. Biochimie. 2013;95(10):1828–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biochi.2013.06.006.

Bianchi G, Martella R, Ravera S, Marini C, Capitanio S, Orengo A M, et al. Fasting induces anti-Warburg effect that increases respiration but reduces ATP-synthesis to promote apoptosis in colon cancer models. Oncotarget. 2015;6(14):11806–11819. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.3688.

Ravera S, Bartolucci M, Cuccarolo P, Litamè E, Illarcio M, Calzia D, et al. Oxidative stress in myelin sheath: the other face of the extramitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation ability. Free Radic Res. 2015;49:1156–64. https://doi.org/10.3109/10715762.2015.1050962.

Marini C, Bianchi G, Buschiazzo A, Ravera S, Martella R, Bottoni G, et al. Divergent targets of glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation result in additive effects of metformin and starvation in colon and breast cancer. Sci Rep. 2016;6:19569. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep19569.

Costes SV, Daelemans D, Cho EH, Dobbin Z, Pavlakis G, Lockett S. Automatic and quantitative measurement of protein-protein colocalization in live cells. Biophys J. 2004;86:3993–4003. https://doi.org/10.1529/biophysj.103.038422.

Ceccarelli J, Delfino L, Zappia E, Castellani P, Borghi M, Ferrini S, Tosetti F, Rubartelli A. The redox state of the lung cancer microenvironment depends on the levels of thioredoxin expressed by tumor cells and affects tumor progression and response to prooxidants. Int J Cancer. 2008;123(8):1770–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.23709.

Marini C, Morbelli S, Armonino R, Spinella G, Riondato M, Massollo M, et al. Direct relationship between cell density and FDG uptake in asymptomatic aortic aneurysm close to surgical threshold: an in vivo and in vitro study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2012;39(1):91–101. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-011-1955-1.

MacNeil LG, Baker SK, Stevic I, Tarnopolsky MA. 17β-estradiol attenuates exercise-induced neutrophil infiltration in men. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2011;300(6):R1443–51. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpregu.00689.2009.

Chistiakov DA, Myasoedova VA, Revin VV, Orekhov AN, Bobryshev Y. The impact of interferon-regulatory factors to macrophage differentiation and polarization into M1 and M2. Immunobiology. 2018;223(1):101–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.imbio.2017.10.005.

Mackey AL, Kjaer M. The breaking and making of healthy adult human skeletal muscle in vivo. Skelet Muscle. 2017;7(1):24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13395-017-0142-x.

Reidy PT, Lindsay CC, McKenzie AI, Fry CS, Supiano MA, Marcus RL, et al. Aging-related effects of bed rest followed by eccentric exercise rehabilitation on skeletal muscle macrophages and insulin sensitivity. Exp Gerontol. 2018;107:37–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exger.2017.07.001.

Ambarus CA, Krausz S, van Eijk M, Hamann J, Radstake TRDJ, Reedquist KA, et al. Systematic validation of specific phenotypic markers for in vitro polarized human macrophages. J Immunol Methods. 2012;375(1-2):196–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jim.2011.10.013.

Italiani P, Boraschi D. From monocytes to M1/M2 macrophages: phenotypical vs. functional differentiation. Front Immunol. 2014;5:514. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2014.00514.

Rőszer T. Understanding the mysterious M2 macrophage through activation markers and effector mechanisms. Mediators Inflamm. 2015;2015:816460. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/816460.

Pharaoh G, Sataranatarajan K, Street K, Hill S, Gregston J, Ahn B, Kinter C, Kinter M, Van Remmen H. Metabolic and stress response changes precede disease onset in the spinal cord of mutant SOD1 ALS mice. Front Neurosci. 2019;13:487. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2019.00487.

Joardar A, Manzo E, Zarnescu DC. Metabolic dysregulation in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: challenges and opportunities. Curr Genet Med Rep. 2017;5(2):108–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40142-017-0123-8.

Golko-Perez S, Amit T, Youdim MB, Weinreb O. Beneficial effects of multitarget iron chelator on central nervous system and gastrocnemius muscle in SOD1(G93A) transgenic ALS mice. J Mol Neurosci. 2016;59(4):504–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12031-016-0763-2.

Manzo E, Lorenzini I, Barrameda D, O’Conner AG, Barrows JM, Starr A, et al. Glycolysis upregulation is neuroprotective as a compensatory mechanism in ALS. Elife. 2019;8:e45114. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.45114.

Csala M, Bánhegyi G, Benedetti A. Endoplasmic reticulum: a metabolic compartment. FEBS Lett. 2006;580(9):2160–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.febslet.2006.03.050.

Vander Heiden MG, DeBerardinis RJ. Understanding the intersections between metabolism and cancer biology. Cell. 2017;168(4):657–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2016.12.039.

Evans J.L, Goldfine I D, Maddux B A, Grodsky G M. Oxidative stress and stress-activated signaling pathways: a unifying hypothesis of type 2 diabetes. Endocr Rev. 2002; 23(5):599-622. doi:https://doi.org/10.1210/er.2001-0039.

Lee S, Min KT. The interface between ER and mitochondria: molecular compositions and functions. Mol Cells. 2018;41(12):1000–1007. doi:10.14348/molcells.2018.0438.

Görlach A, Bertram K, Hudecova S, Krizanova O. Calcium and ROS: a mutual interplay. Redox biology. 2015;6:260–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2015.08.010.

Scialo F, Mallikarjun V, Stefanatos R, Sanz A. Regulation of lifespan by the mitochondrial electron transport chain: reactive oxygen species-dependent and reactive oxygen species-independent mechanisms. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;19(16):1953-1969.doi:10.1089/ars.2012.4900.

Esterhazy D, King MS, Yakovlev G, Hirst J. Production of reactive oxygen species by complex I (NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase) from Escherichia coli and comparison to the enzyme from mitochondria. Biochemistry. 2008;47(12):3964–71. https://doi.org/10.1021/bi702243b.

Chaudhari N, Talwar P, Parimisetty A, Lefebvre d'Hellencourt C, Ravanan P. A molecular web: endoplasmic reticulum stress, inflammation, and oxidative stress. Front Cell Neurosci. 2014;8:213. https://doi.org/10.3389/fncel.2014.00213.

Tirasophon W, Welihinda AA, Kaufman RJ. A stress response pathway from the endoplasmic reticulum to the nucleus requires a novel bifunctional protein kinase/endoribonuclease (Ire1p) in mammalian cells. Genes Dev. 1998;12(12):1812–24. https://doi.org/10.1101/gad.12.12.1812.

Harding HP, Zhang Y, Ron D. Protein translation and folding are coupled by an endoplasmic-reticulum-resident kinase [published correction appears in Nature 1999 Mar 4;398(6722):90]. Nature. 1999;397(6716):271–4. https://doi.org/10.1038/16729.

Yoshida H, Okada T, Haze K, Yanagi H, Yura T, Negishi M, et al. ATF6 activated by proteolysis binds in the presence of NF-Y (CBF) directly to the cis-acting element responsible for the mammalian unfolded protein response. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20(18):6755–67. https://doi.org/10.1128/mcb.20.18.6755-6767.2000.

Chung MJ, Suh YL. Ultrastructural changes of mitochondria in the skeletal muscle of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ultrastruct Pathol. 2002;26(1):3–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/01913120252934260.

Vielhaber S, Winkler K, Kirches E, Kunz D, Büchner M, Feistner H, et al. Visualization of defective mitochondrial function in skeletal muscle fibers of patients with sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 1999;169(1-2):133–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-510x(99)00236-1.

Zhou J, Yi J, Fu R, Liu E, Siddique T, Ríos E, et al. Hyperactive intracellular calcium signaling associated with localized mitochondrial defects in skeletal muscle of an animal model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(1):705–12. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M109.041319.

Manfredi G, Kawamata H. Mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum crosstalk in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurobiol Dis. 2016;90:35–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbd.2015.08.004.

Favaro G, Romanello V, Varanita T, Desbats MA, Morbidoni V, Tezze C, et al. DRP1-mediated mitochondrial shape controls calcium homeostasis and muscle mass. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):2576. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-10226-9.

Friedman JR, Lackner LL, West M, DiBenedetto JR, Nunnari J, Voeltz GK. ER tubules mark sites of mitochondrial division. Science. 2011;334(6054):358–62. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1207385.

Tezze C, Romanello V, Desbats M A, Fadini G P, Albiero M, Favaro G, et al. Age-associated loss of OPA1 in muscle impacts muscle mass, metabolic homeostasis, systemic inflammation, and epithelial senescence. Cell Metab. 2017;25(6):1374–1389.e6. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2017.04.021.

Zhou J, Chong SY, Lim A, Singh B K , Sinha R A, Salmon A B, et al. Changes in macroautophagy, chaperone-mediated autophagy, and mitochondrial metabolism in murine skeletal and cardiac muscle during aging. Aging (Albany NY). 2017;9(2):583–599. doi:10.18632/aging.101181.

Touvier T, De Palma C, Rigamonti E, Scagliola A, Incerti E, Mazelin L, et al. Muscle-specific Drp1 overexpression impairs skeletal muscle growth via translational attenuation. Cell Death Dis. 2015;6(2):e1663. https://doi.org/10.1038/cddis.2014.595.

Menzies FM, Ince PG, Shaw PJ. Mitochondrial involvement in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurochem Int. 2002;40(6):543–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0197-0186(01)00125-5.

Mattiazzi M, D'Aurelio M, Gajewski CD, Martushova K, Kiaei M, Beal MF, et al. Mutated human SOD1 causes dysfunction of oxidative phosphorylation in mitochondria of transgenic mice. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(33):29626–33. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M203065200.

Echaniz-Laguna A, Zoll J, Ponsot E, N’Guessan B, Tranchant C, Loeffler JP, Lampert E. Muscular mitochondrial function in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis is progressively altered as the disease develops: a temporal study in man. Exp Neurol. 2006;198(1):25–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.07.020.

Krasnianski A, Deschauer M, Neudecker S, Gellerich FN, Müller T, Schoser BG, et al. Mitochondrial changes in skeletal muscle in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and other neurogenic atrophies. Brain. 2005;128(Pt 8):1870–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awh540.

Hirst J, King MS, Pryde KR. The production of reactive oxygen species by complex I. Biochem Soc Trans. 2008;36(Pt 5):976–80. https://doi.org/10.1042/BST0360976.

Rosenbohm A, Schmid B, Buckert D, Rottbauer W, Kassubek J, Ludolph AC, et al. Cardiac findings in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a magnetic resonance imaging study. Front Neurol. 2017;8:479. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2017.00479.

Mori F, Tada M, Kon T, Miki Y, Tanji K, Kurotaki H, et al. Phosphorylated TDP-43 aggregates in skeletal and cardiac muscle are a marker of myogenic degeneration in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and various conditions. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2019;7(1):165. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40478-019-0824-1.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Funding

This work was supported by the grant AIRC “chemotherapy effect on cell energy metabolism and endoplasmic reticulum redox control” (IG 23201).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

(1) Conception and design or analysis and interpretation of data, or both: CM, VC, TB, GBB, and GS. (2) Drafting of the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content: all authors. (3) Animal experiments: MM, TB, CT, SC, LE, VC, and AMO. (4) Ex vivo experiments: VC, SB, PC, SR, KC, and CV. (5) Biochemical analysis: PC, PP, SB, SR, and FG. (6) Electron microscopy: CV, KC, and RF. (7) Image analysis and image processing: CM, VC, MB, SM, MID, AM, SR, and SM. (8) Statistic analysis of data: CM, VC, AS, and GS. (9) Final approval of the manuscript submitted: all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures involving animals were performed in respect of the current National and International regulations and were reviewed and approved by the Licensing and Animal Welfare Body of the IRCCS Ospedale Policlinico San Martino, Genova, Italy, and by the Italian Ministry of Health.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

Silvia Morbelli received speaker honoraria from General Electric and Eli-Lilly. The other authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Supplementary Table 1.

Statistical parameters of Independent Samples Test

Additional file 2: Supplementary Table 2.

PET imaging data

Additional file 3.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 4.

Suppl Figure

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Marini, C., Cossu, V., Bonifacino, T. et al. Mechanisms underlying the predictive power of high skeletal muscle uptake of FDG in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. EJNMMI Res 10, 76 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13550-020-00666-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13550-020-00666-6