Abstract

Background

Plasma neurofilament light (NFL) and total Tau (t-Tau) proteins are candidate biomarkers for early stages of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). The impact of biological factors on their plasma concentrations in individuals with subjective memory complaints (SMC) has been poorly explored. We longitudinally investigate the effect of sex, age, APOE ε4 allele, comorbidities, brain amyloid-β (Aβ) burden, and cognitive scores on plasma NFL and t-Tau concentrations in cognitively healthy individuals with SMC, a condition associated with AD development.

Methods

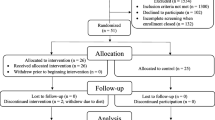

Three hundred sixteen and 79 individuals, respectively, have baseline and three-time point assessments (at baseline, 1-year, and 3-year follow-up) of the two biomarkers. Plasma biomarkers were measured with an ultrasensitive assay in a mono-center cohort (INSIGHT-preAD study).

Results

We show an effect of age on plasma NFL, with women having a higher increase of plasma t-Tau concentrations compared to men, over time. The APOE ε4 allele does not affect the biomarker concentrations while plasma vitamin B12 deficiency is associated with higher plasma t-Tau concentrations. Both biomarkers are correlated and increase over time. Baseline NFL is related to the rate of Aβ deposition at 2-year follow-up in the left-posterior cingulate and the inferior parietal gyri. Baseline plasma NFL and the rate of change of plasma t-Tau are inversely associated with cognitive score.

Conclusion

We find that plasma NFL and t-Tau longitudinal trajectories are affected by age and female sex, respectively, in SMC individuals. Exploring the influence of biological variables on AD biomarkers is crucial for their clinical validation in blood.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Plasma neurofilament light (NFL) chain and total Tau (t-Tau) proteins are promising biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). They show good/fair diagnostic accuracy to distinguish cognitively healthy individuals from AD patients, when ultrasensitive technologies of measurement are used [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. Both proteins are involved in the physiological processes of neuronal integrity [8, 9]. Both plasma t-Tau and NFL are associated with worsening rate of cognitive performance [3, 10,11,12,13], cerebral atrophy [2, 3, 12,13,14], and hypometabolism [2, 3, 12] in prodromal and dementia phases of AD. Only a few studies investigated these biomarkers, either separately [15,16,17,18] or in combination [3], during the preclinical stages of sporadic AD. Even less data are available on the effect of key biological factors—such as age, sex, and APOE ε4 allele—on plasma NFL and t-Tau concentrations. At our knowledge, there are no studies investigating the potential contribution of comorbidities in affecting either plasma NFL or t-Tau concentrations, and no evidence on the impact of these key biological factors on plasma NFL and t-Tau concentrations in populations with SMC, a condition associated with AD development.

Our primary aims are to investigate, in a cohort of cognitively intact individuals with subjective memory complaints (SMC), the dynamic trajectories of plasma NFL and t-Tau concentrations and the impact of sex, age, and APOE genotype. Secondary aims are (1) to identify, at baseline, the variables maximally contributing to group separation of individuals above or below the third quartile for baseline NFL and t-Tau concentrations, respectively; (2) to investigate the association of the two plasma biomarkers, at baseline, with baseline global and regional brain amyloid-β (Aβ) deposition, Aβ changes deposition, baseline Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score, Free and Cued Selective Rating Test (FCSRT), the concentrations of the corresponding cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers (CSF NFL and CSF t-Tau), and between each other; and (3) to explore the association of NFL and t-Tau changes with MMSE and FCSRT modifications.

Materials and methods

We performed a longitudinal investigation in 316 SMC participants of the French monocentric “INveStIGation of AlzHeimer’s PredicTors in Subjective Memory Complainers” (INSIGHT-preAD) cohort (Pitié-Salpêtrière University Hospital, Paris) [19]. All participants underwent two Aβ-positron emission tomography (Aβ-PET) scans, at baseline and at 2-year follow-up. A subset of 40 individuals received a baseline lumbar puncture. The concentrations of plasma NFL and t-Tau were measured at three time points using an ultrasensitive technology (N = 79 at baseline, 1-year, and 3-year follow-up).

Study participants

We designed a large-scale mono-centric research program using a cohort of SMC recruited from the INSIGHT-preAD study, a French academic university-based cohort [19] which is part of the Alzheimer Precision Medicine Initiative (APMI) and its Cohort Program (APMI-CP) [20,21,22,23]. Participants were enrolled between May 25, 2013, and January 20, 2015, at the Institute of Memory and Alzheimer’s disease (Institut de la Mémoire et de la Maladie d’Alzheimer, IM2A) at the Pitié-Salpêtrière University Hospital in Paris, France [19]. The study was conducted in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki of 1975 and approved by the local Institutional Review Board at the participating center. All participants gave written informed consent for use of their clinical data for research purposes.

PET data acquisition and processing

All Florbetapir-PET scans were acquired in a single session on a Philips Gemini GXL CT-PET scanner 50 (± 5) min after injection of approximately 370 MBq (333–407 MBq) of Florbetapir. Images acquisition, reconstruction including correction algorithms and reallination, averaging, and quality check were performed by the CATI team (Centre d’Acquisition et Traitement des Images) (http://cati-neuroimaging.com) [19, 24, 25] and were calculated for each of 12 cortical regions of interest (right and left posterior cingulate, right and left anterior cingulate, right and left superior frontal, right and left inferior parietal, right and left precuneus, right and left middle temporal cortices), as well as the global average standard uptake value ratio (SUVR).

CSF sampling and biomarkers assessment

CSF sampling was performed by lumbar puncture in a subsample of 40 individuals. All CSF samples were collected in polypropylene tubes, centrifuged at 1000 g for 10 min at + 4 °C. The collected supernatant was stored at − 80 °C for pending biochemical analysis. The immunoassays for CSF core biomarkers are reported in previous studies [26, 27].

Blood sampling and collection tube storage

Ten (10) mL of venous blood were collected in one BD Vacutainer® spray-coated K2 tube, which was employed for all subsequent immunological analyses. Blood samples were taken in the morning, after a 12-h fast, handled in a standardized way, and centrifuged for 15 min at 2000 G-force at + 4 °C. Per sample, plasma fraction was collected, homogenized, aliquoted into multiple 0.5 mL cryovial-sterilized tubes, and finally stored at − 80°Cwithin 2 h from collection.

Immunoassays for plasma biomarkers

All analyses of plasma t-Tau and NFL concentrations were performed at the Clinical Neurochemistry Laboratory, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Sweden [28,29,30]. In particular, a volume of 0.5 mL of plasma for each individual was required for performing the analyses.

Plasma t-Tau concentrations were measured using the Human Total Tau 2.0 kit on the ultrasensitive single molecule arrays (Simoa) platform (Quanterix, Lexington, MA), according to the manufacturer instructions.

For plasma t-Tau, both repeatability and intermediate precision were 12.2% for an internal QC plasma sample with a concentration of 1.9 pg/mL [2, 30]. The t-Tau assay was originally developed in a collaboration between the Clinical Neurochemistry Laboratory and Quanterix [31]. However, the commercially available assay was built on this work but with another set of antibodies.

Plasma NFL concentrations were measured using the ultrasensitive Simoa technology, according to the manufacturer instructions. Repeatability was 9.6% and 10.6% and intermediate precision was 14.6% and 11.6% for two internal QC plasma samples with concentrations of 12.9 pg/mL and 107 pg/mL [28,29,30]. The NFL assay was originally developed by the Clinical Neurochemistry Laboratory and then commercialized by Quanterix [32].

All samples were analyzed on one occasion using one batch of reagents by board-certified laboratory technicians who were blinded to clinical data.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM-SPSS® Statistics, Version 20, and Addinsoft, XLSTAT Statistical and Data Analysis Solution (2019), Long Island, NY, USA, statistical packages for Mac OS X.

Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was applied to check for normality. Gaussian distributed values were expressed as mean and standard deviation (SD) or standard error (SE); otherwise, median and interquartile range (IR) were used for quantitative variables, while categorical data were expressed as frequency.

To evaluate the impact of age, sex, and APOE ε4 carrier status on NFL and t-Tau evolution in a 3-year follow-up, respectively, we conducted two independent linear mixed-effects models (LMM) on the whole sample [33]. Age, sex, and APOE ε4 carrier status were included as fixed effects in the model and each individual as random effect. We also included interaction between age and sex, age and APOE ε4 carrier status, and sex and APOE ε4 carrier status. Type III likelihood ratio tests were used to test each fixed effect and interaction. The statistical models used were verified for normal distribution of residuals, random effects, and homoscedasticity of residuals. Subsequently, the analysis was repeated after stratifying the sample into amyloid-PET-negative and positive individuals.

On the whole sample, cross-sectional data were also elaborated to identify the variables maximally contributing to group separation of individuals, based on the following outcome variables Y: baseline plasma NFL and baseline plasma t-Tau. To this end, two partial least square (PLS) models were generated, and the variables with Variable Importance in Projection (VIPs, expressing a measure of a variable’s relevance in the model) greater than 1.50 were considered significant for separation of the sample [34, 35]. In the first model, Y was defined by placing NFL = 1 whether NFL concentrations were above or below the third quartile, and 0 if below. Input variables were sex, age, APOE ε4 carrier status, arterial hypertension, (HTA), atrial fibrillation, heart disease, dyslipidemia, diabetes, obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS), head trauma, mood disorders, vitamin B12 deficiency, body mass index (BMI), global SUVR, MMSE and FCSRT at baseline, and baseline plasma t-Tau. In the second model, input variables were the same, as previously described, but the outcome variable Y was t-Tau, categorized as 1 if t-Tau concentrations were upper than the third quartile, and 0 otherwise.

The associations of the two plasma biomarkers at baseline with baseline global and regional brain Aβ deposition, Δ Aβ deposition, baseline MMSE score, FCSRT, the corresponding CSF biomarkers, and between each other were evaluated by Spearman correlation testing. If the relationship was significant, a subsequent stepwise forward regression was performed. Spearman test was used to explore the association of Δ NFL and Δ t-Tau with Δ MMSE and Δ FCSRT (cognitive measures). Δ value has been defined as the difference between the baseline and the 3-year follow-up value, excluding for Aβ deposition where we considered 2-year follow-up value, because we had the baseline data available and after 2 years.

Variables with skewed distribution were log-transformed for use in all parametric analyses. P values < 0.05 were considered significant in all statistical elaboration.

Results

The clinical and demographic baseline characteristics of the 316 participants also stratified by sex are reported in Table 1. Seventy-nine individuals had all time point plasma samples (at baseline, 1-year, and 3-year follow-up). In these individuals, NFL and t-Tau longitudinal data (Figs. 1a and 2a), also stratified by sex (Figs. 1b and 2b), using within person trajectories (Figs. 1c and 2c), are shown. After a 3-year follow-up, six SMC individuals (~ 2%) clinically progressed to mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or dementia (Table 1S).

Plasma NFL changes overtime. The first graph (a) showed repeated measurements at baseline (T0), 1-year follow-up (T1), and 3-year follow-up (T2). The second one (b) charted differences for plasma NFL concentrations stratified by sex at the three time points. The third graph (c) reported within person plasma NFL trajectories. Data are referred to a subset of SMC (N = 79) who performed T0, T1, and T2 blood samples. Abbreviations: F, female; M, male; NFL, neurofilament light chain; SMC, subjective memory complainers; t-Tau, total Tau; T0, baseline; T1, 1-year follow-up; T2, 3-year follow-up

Plasma t-Tau changes overtime. The first graph (a) showed repeated measurements at baseline (T0), 1-year follow-up (T1), and 3-year follow-up (T2). The second one (b) charted differences for plasma t-Tau concentrations stratified by sex at the three time points. The third graph (c) reported within person plasma t-Tau trajectories. Data are referred to a subset of SMC (N = 79) who performed T0, T1, and T2 blood samples. Abbreviations: F, female; M, male; NFL, neurofilament light chain; SMC, subjective memory complainers; t-Tau, total Tau; T0, baseline; T1, 1-year follow-up; T2, 3-year follow-up

Plasma NFL, t-Tau biomarkers and biological variables

The impact of biological factors on plasma biomarkers concentration over time

Table 2 summarizes the main effects investigated for NFL and t-Tau, respectively. For the whole sample, we found a significant effect of age on plasma NFL concentrations (P < 0.001), but not of sex and of age*sex interaction. When we performed a post hoc analysis, after dividing the sample into groups of less than and above 76 years of age (value corresponding to average, median and mode), the individuals over 76 years of age showed higher NFL values in all time points considered (mean and SE at baseline: 32.5 ± 1.1 and 27.0 ± 0.9 pg/mL, respectively, P < 0.001; at 1-year follow-up: 34.8 ± 1.4 and 27.6 ± 1.2 pg/mL, respectively, P < 0.001; at 3-year follow-up: 58.2 ± 3.5 and 49.9 ± 2.7 pg/mL, respectively, P = 0.049). When we repeated the analysis, after stratifying by cerebral amyloid-PET-negative and amyloid-PET-positive individuals, we have obtained comparable results. In the amyloid-PET-negative subgroup, the post hoc analysis, after dividing the sample into subsets of less than and above 76 years of age, the individuals over 76 years of age showed higher NFL values in all time points considered (mean and SE at baseline: 31.3 ± 1.3 and 26.2 ± 1.0 pg/mL, respectively, P = 0.002; at 1 year: 33.6 ± 1.8 and 28.1 ± 1.5 pg/mL, respectively, P = 0.019; at 3 years: 53.8 ± 2.5 and 47.2 ± 2.3 pg/mL, respectively, P = 0.050). Again, in amyloid-PET-positive individuals, those over 76 years of age reported higher NFL values (mean and SE at baseline: 35.1 ± 2.1 and 30.4 ± 2.4 pg/mL, respectively, P = 0.050; at 1 year: 38.0 ± 2.6 and 27.3 ± 2.7 pg/mL, respectively, P = 0.006; at 3 years: 67.8 ± 3.9 and 57.6 ± 3.9 pg/mL, respectively, P = 0.049).

APOE ε4 allele had no effect on the total sample and amyloid-PET-negative individuals. However, on amyloid-PET-positive individuals, at 3 years of follow-up, NFL was significantly higher in ε4+ individuals compared to ε4- (mean and SE: 64.1 ± 7.3 and 46.2 ± 3.3 pg/mL, respectively, P = 0.040). No interaction with APOE ε4 carrier status was found in any group.

In the total sample, a significant effect of sex on plasma t-Tau concentrations was reported, displaying higher means in female than in male individuals (P = 0.001) (Table 2). The significant sex*age interaction (P = 0.038) indicated that this effect was not the same among the different ages. In particular, at 3 years of follow-up, t-Tau concentrations were higher in male individuals aged more than 76 years than in those younger (mean and SE = 6.2 ± 0.8 and 4.5 ± 0.3 pg/mL, respectively, P = 0.040) but not in women (mean and SE = 5.2 ± 0.3 and 5.7 ± 0.4 pg/mL, respectively, P = 0.359). No significant differences in male or female individuals for baseline and 1 year of follow-up have been observed. When we repeated the analysis, after stratifying participants in cerebral amyloid PET negative and positive, we found similar results in both subgroups, with no significant difference for the baseline and at 1 year of follow-up. Regarding the 3-year follow-up, for amyloid positive individuals, t-Tau concentrations were higher in males aged more than 76 years than in those younger (mean and SE: 7.6 ± 2.1 and 5.5 ± 1.9 pg/mL, respectively, P = 0.048), but not in women (mean and SE = 4.9 ± 0.6 and 6.4 ± 1.2 pg/mL, respectively, P = 0.220). We found similar results in amyloid-PET-negative individuals: higher concentrations in men aged more than 76 years than in those younger (mean and SE: 5.5 ± 0.6 and 4.0 ± 0.3 pg/mL, respectively, P = 0.032) and not in women (mean and SE: 5.5 ± 0.4 and 5.4 ± 0.3 pg/mL, respectively, P = 0.886). We did not detect a significant effect of APOE ε4 allele on plasma t-Tau concentrations nor a significant interaction between APOE ε4 allele and sex, nor between APOE ε4 allele and age, both in the total sample and after splitting whole sample in amyloid-PET-negative and positive individuals.

Biological factors contributing to high baseline plasma biomarker concentrations

Using baseline NFL as a dependent variable, PLS identified the following variables separating the sample on the basis of NFL concentrations above or below the third quartile: age (VIPs = 2.74) and plasma baseline t-Tau (VIPs = 1.53). The participants with NFL concentration above the third quartile are older and had higher t-Tau concentrations than the others (Table 3). In the second PLS model, the parameters identifying individuals with t-Tau = 0/1 were plasma vitamin B12 deficiency (VIPs = 2.48) and sex (VIPs = 1.83). Individuals with plasma t-Tau concentrations above the third quartile (t-Tau = 1) were more significantly represented by women than men (females = 76%, males = 24%). Individuals with plasma vitamin B12 deficiency showed plasma t-Tau concentrations above the upper quartile (Table 3).

Plasma biomarkers and cerebral amyloid load

No association between baseline plasma NFL or t-Tau concentrations and both baseline and 2-year follow-up cerebral Aβ deposition were reported. Baseline plasma NFL concentrations were weakly associated with global brain amyloid increase over time (Δ SUVR, ρs = 0.15; P = 0.030). When a subsequent stepwise forward regression using baseline plasma NFL as a dependent variable was performed, a relationship with Δ amyloid deposition in the left posterior cingulate and in the bilateral inferior parietal gyri has been observed (r = 0.13; P = 0.019 and r = 0.14; P = 0.013, respectively). Furthermore, baseline plasma NFL concentration was associated with plasma t-Tau (ρs = 0.18; P = 0.011) and CSF NFL (ρs = 0.90; P < 0.001). In Table 4, we charted a summary of the associations between plasma biomarkers and cerebral amyloid load.

Plasma biomarkers and cognition

No association between baseline plasma NFL or t-Tau concentrations and baseline MMSE score or FCSRT was observed. Baseline plasma NFL concentrations negatively correlated with MMSE at 3-year follow-up (ρs = − 0.13; P = 0.029). No association with FCSRT was observed. Δ t-Tau correlated inversely with MMSE (ρs = − 0.19; P = 0.015) and positively with Δ NFL (ρs = 0.30; P < 0.001) at the 3-year follow-up. In Table 4, we reported a summary of the associations between plasma biomarkers and MMSE and FCSRT scores.

Discussion

We performed a study on both plasma t-Tau and NFL concentrations longitudinally assessed in a monocentric cohort of cognitively normal individuals with SMC. We found that both plasma t-Tau and NFL concentrations increased over time in our preclinical population. Women had a higher increase of plasma t-Tau concentrations over time compared to men. A positive interaction between female sex and aging to determine a longitudinal increase of t-Tau was also observed. To our knowledge, no other studies reported a significant association between plasma t-Tau concentrations and sex though a higher concentration of tau in CSF of females with AD was reported compared to men [36]. This may depend on differences in sex hormones with a suggested protective role of testosterone against the hyperphosphorylation of tau [36]. Indeed, it is well-known that AD is more prevalent in females than males [37]. We hypothesize that, in our sample, females with SMC showing increased plasma t-Tau concentrations might more probably progress to AD compared to males. These findings indicated that sex-specific reference values may be considered for plasma t-Tau biomarker. By contrast, we showed that sex did not impact plasma NFL concentrations. Indeed, Mattsson and colleagues did not report any sex association in a large cohort including prodromal and AD participants, while two other studies showed an association with men and women, respectively [11, 38]. Although only in CSF, NFL concentrations were higher in men than women in a large meta-analysis of healthy controls and several neurodegenerative diseases including AD [39]. Finally, the association between plasma NFL concentrations and sex remained uncertain and should be elucidated by further longitudinal studies [3, 10].

Age impacted plasma NFL concentrations over time and was associated with plasma NFL. This finding confirms the well-known relationship between aging and NFL [5, 40, 41], though not reported in some diagnostic categories (e.g., multiple sclerosis and Creutzfeldt Jacob disease) [39, 41]. Aging and relative subclinical cerebrovascular alterations per se convey to a subtle neuronal damage and, consequently, the release of axonal byproducts, such as NFL, into body fluids [29, 41, 42]. The relationship between plasma NFL increase and age should be clarified in future studies. Finally, we did not exclude that a high impact of age on plasma NFL concentrations might mask a potential sex effect in our relatively small size cohort. By contrast, plasma t-Tau does not seem to be strictly related to age. However, the positive interaction between female sex and aging, which indicates a longitudinal increase of t-Tau in males, should be further investigated.

Results obtained for SMC individuals did not suggest the presence of higher concentrations of both plasma NFL and t-Tau in APOE ɛ4 carriers than in non-carriers. This finding is in line with previous studies that did not indicate significant differences between APOE ɛ4 carriers and non-carriers in terms of plasma NFL concentrations [5, 40]. On the other hand, no association of plasma t-Tau with APOE ε4 carrier status assessment was shown [3].

The PLS analysis confirmed that age was associated with baseline plasma NFL, whereas female sex with baseline plasma t-Tau concentrations. Additionally, plasma vitamin B12 deficiency was related to baseline plasma t-Tau concentrations. This last finding is of particular clinical relevance and further studies are needed to investigate the potential interaction of t-Tau and vitamin B12 concentrations in blood. A further independent study may check this finding out verifying if this result holds true. In case, a trial with vitamin B12 dietary supplement may be proposed for preclinical individuals with SMC followed with serial plasma t-Tau measurements.

Plasma NFL concentrations weakly correlated with cortical amyloid load deposition at baseline. Plasma NFL was also associated to increased cortical amyloid deposition, at 2-year follow-up, in the left posterior cingulate cortex and bilateral inferior parietal cortex. Interestingly, these areas are part of the default mode network that is functionally impaired in AD [43, 44]. Our analysis indicated an effect of high baseline plasma NFL concentrations on the deposition of amyloid plaques in the brain in a population with SMC. In addition, NFL was significantly higher in amyloid-PET-positive APOE ε4+ allele carriers compared to the ε4− ones at 3 years of follow-up. However, our analysis did not distinguish SMC converters to MCI or dementia from non-converters. In a previous investigation on SMC individuals, only a trend of higher plasma NFL concentrations was described in amyloid-PET-positive SMC participants versus amyloid-PET-negative ones [16]. Other studies evaluating the more advanced prodromal and dementia stages of AD did not demonstrate any association between cerebral amyloid load and plasma NFL concentrations [3, 45]. Finally, the relationship between plasma NFL concentrations and cortical amyloid deposition should be further elucidated.

We demonstrated a cross-sectional and longitudinal association between plasma NFL and t-Tau concentrations. Moreover, the rate of increase of the two plasma biomarkers was related. There is only one previous longitudinal study reporting an association between plasma NFL and t-Tau in a pooled cohort of AD, MCI, and cognitively healthy controls [3]. This suggests that both biomarkers may reflect common neurodegenerative mechanisms in preclinical individuals with SMC.

In line with other studies [5], we found a strong correlation between plasma and CSF NFL concentrations in a subset sample of our SMC individuals [5]. The strict association between plasma and CSF NFL concentrations suggests that NFL alterations in peripheral fluids mirror those occurring in the central nervous system [46].

Baseline plasma NFL concentrations were associated with a 3-year follow-up decline of MMSE score. Our findings are partially in line with those of other studies on prodromal AD and AD dementia [3, 10, 11, 45, 47, 48] and with a study on preclinical AD individuals [16]. The rate of change of t-Tau, but not of NFL, was associated with a decrease in MMSE score at three-year follow-up. The use of serial plasma biomarker measurements and the rate of change of concentrations over time may be more reliable than absolute values, at a single time point, in differentiating patients with neurodegenerative diseases from controls [47]. In this regard, a recent study confirmed that the rate plasma t-Tau increase may be predictive of the dementia development and be adopted as a biomarker for risk stratification [13].

Finally, the lack of associations of NFL and t-Tau with a decrease in FCSRT score over time here reported is possibly due to the relative short length of follow-up and the low rate of conversion in our SMC population (N = 6 persons, 2%). Therefore, our results on cognitive decline should be cautiously considered as a preliminary.

Limitations of study

Our study presents some caveats. First, the low number of converters (SMC-MCI and SMC-dementia) does not allow any definitive conclusions on the role of plasma NFL and t-Tau in predicting cognitive worsening over time in preclinical individuals with SMC. Furthermore, we miss some sample collection along the time points, and we lack imaging data regarding brain metabolism and atrophy. Potential effects of genetic polymorphisms other than APOE ε4 allele on modifications of plasma NFL and t-Tau concentrations could not be ruled out. The t-Tau assay does not have a good linearity and parallelism and our results need to be confirmed in further investigations.

Conclusion and future direction

We reported significantly increased concentrations of plasma t-Tau in female sex and the potential association of plasma vitamin B12 deficiency with plasma t-Tau concentrations. We confirmed the significant association of plasma NFL concentrations with age and the correlation with its CSF concentrations. It was a potential predictor of longitudinal cerebral amyloid deposition in specific brain areas associated with AD pathophysiology. Rate of changes of plasma t-Tau may predict longitudinal worsening of cognition in SMC individuals. We also supported previous results reporting no association between plasma NFL and t-Tau with APOE ε4 allele. In this regard, age, sex, and APOE ε4 allele combined with plasma NFL and t-Tau may be used to establish a risk stratification score integrating different information on the development of dementia.

In light of our findings, we believe that the impact of biological variables needs to be critically assessed in the biomarker discovery and development process for AD diagnosis [49]. Moreover, our results should not be generalizable to other more specific settings (e.g., clinical population studies), different geographies, and ethnic groups.

Exploring the impact of these biological variables on the concentrations and longitudinal trajectories of plasma NFL and t-Tau in cognitively normal individuals, independently of their stability or their development of cognitive decline over time, is crucial to define the potential role of plasma NFL and t-Tau as diagnostic, prognostic, and theragnostic biomarkers. Importantly, our study also suggested that NFL and t-Tau seem not to be considerably influenced by comorbidities and vascular risk factors and remain relatively stable. Indeed, these steps will allow to better delineate their potential context-of-use for different settings, including clinical practice and pharmacological trials. In this respect, the recruitment of individuals for clinical trials will be improved using pathophysiological blood-based biomarkers detecting individuals at risk for progression and decline. We foresee the option to enter a novel era of next-generation biomarker-guided targeted therapies for AD and other neurodegenerative diseases under the paradigm of precision medicine [50].

Availability of data and materials

The dataset generated and analyzed in the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AD:

-

Alzheimer’s disease

- APMI:

-

Alzheimer Precision Medicine Initiative

- Aβ1–42 :

-

Amyloid-β 1 to 42

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- HTA:

-

Arterial hyperthension

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CSF:

-

Cerebrospinal fluid

- FCSRT:

-

Free and Cued Selective Rating Test

- INSIGHT-preAD:

-

INveStIGation of AlzHeimer’s PredicTors in Subjective Memory Complainers”

- LMM:

-

Linear mixed models

- MCI:

-

Mild cognitive impairment

- MMSE:

-

Mini-Mental State Examination

- OSAS:

-

Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome

- NFL:

-

Neurofilament light chain

- PLS:

-

Two partial least square

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SMC:

-

Subjective memory complaint

- SUVR:

-

Standard uptake value ratios

- t-Tau:

-

Total Tau

- VIPs:

-

Variable Importance in Projection

References

Molinuevo JL, Ayton S, Batrla R, Bednar MM, Bittner T, Cummings J, et al. Current state of Alzheimer’s fluid biomarkers. Acta Neuropathol (Berl). 2018;136:821–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-018-1932-x.

Mattsson N, Zetterberg H, Janelidze S, Insel PS, Andreasson U, Stomrud E, et al. Plasma tau in Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2016;87:1827–35. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000003246.

Mattsson N, Andreasson U, Zetterberg H, Blennow K. Alzheimer’s disease neuroimaging initiative. Association of plasma neurofilament light with neurodegeneration in patients with Alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74:557–66. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.6117.

Hampel H, O’Bryant SE, Molinuevo JL, Zetterberg H, Masters CL, Lista S, et al. Blood-based biomarkers for Alzheimer disease: mapping the road to the clinic. Nat Rev Neurol. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41582-018-0079-7.

Khalil M, Teunissen CE, Otto M, Piehl F, Sormani MP, Gattringer T, et al. Neurofilaments as biomarkers in neurological disorders. Nat Rev Neurol. 2018;14:577–89. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41582-018-0058-z.

Lue L-F, Sabbagh MN, Chiu M-J, Jing N, Snyder NL, Schmitz C, et al. Plasma levels of Aβ42 and tau identified probable Alzheimer’s dementia: findings in two cohorts. Front Aging Neurosci. 2017;9:226. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2017.00226.

Xia J, Broadhurst DI, Wilson M, Wishart DS. Translational biomarker discovery in clinical metabolomics: an introductory tutorial. Metabolomics Off J Metabolomic Soc. 2013;9:280–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11306-012-0482-9.

Kinnunen KM, Greenwood R, Powell JH, Leech R, Hawkins PC, Bonnelle V, et al. White matter damage and cognitive impairment after traumatic brain injury. Brain J Neurol. 2011;134:449–63. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awq347.

Shahim P, Tegner Y, Gustafsson B, Gren M, Ärlig J, Olsson M, et al. Neurochemical aftermath of repetitive mild traumatic brain injury. JAMA Neurol. 2016;73:1308–15. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.2038.

Zhou W, Zhang J, Ye F, Xu G, Su H, Su Y, et al. Plasma neurofilament light chain levels in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci Lett. 2017;650:60–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2017.04.027.

Lin Y-S, Lee W-J, Wang S-J, Fuh J-L. Levels of plasma neurofilament light chain and cognitive function in patients with Alzheimer or Parkinson disease. Sci Rep. 2018;8:17368. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-35766-w.

Mattsson N, Cullen NC, Andreasson U, Zetterberg H, Blennow K. Association between longitudinal plasma neurofilament light and neurodegeneration in patients with Alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurol. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.0765.

Pase MP, Beiser AS, Himali JJ, Satizabal CL, Aparicio HJ, DeCarli C, et al. Assessment of plasma total tau level as a predictive biomarker for dementia and related endophenotypes. JAMA Neurol. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.4666.

Dage JL, Wennberg AMV, Airey DC, Hagen CE, Knopman DS, Machulda MM, et al. Levels of tau protein in plasma are associated with neurodegeneration and cognitive function in a population-based elderly cohort. Alzheimers Dement J Alzheimers Assoc. 2016;12:1226–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2016.06.001.

Park J-C, Han S-H, Yi D, Byun MS, Lee JH, Jang S, et al. Plasma tau/amyloid-β1-42 ratio predicts brain tau deposition and neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain J Neurol. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awy347.

Chatterjee P, Goozee K, Sohrabi HR, Shen K, Shah T, Asih PR, et al. Association of plasma neurofilament light chain with neocortical amyloid-β load and cognitive performance in cognitively normal elderly participants. J Alzheimers Dis JAD. 2018;63:479–87. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-180025.

Mielke MM, Hagen CE, Wennberg AMV, Airey DC, Savica R, Knopman DS, et al. Association of plasma total tau Level with cognitive decline and risk of mild cognitive impairment or dementia in the Mayo Clinic study on aging. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74:1073–80. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.1359.

Müller S, Preische O, Göpfert JC, Yañez VAC, Joos TO, Boecker H, et al. Tau plasma levels in subjective cognitive decline: results from the DELCODE study. Sci Rep. 2017;7:9529. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-08779-0.

Dubois B, Epelbaum S, Nyasse F, Bakardjian H, Gagliardi G, Uspenskaya O, et al. Cognitive and neuroimaging features and brain β-amyloidosis in individuals at risk of Alzheimer’s disease (INSIGHT-preAD): a longitudinal observational study. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17:335–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30029-2.

Hampel H, O’Bryant SE, Castrillo JI, Ritchie C, Rojkova K, Broich K, et al. PRECISION MEDICINE - the golden gate for detection, treatment and prevention of Alzheimer’s disease. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2016;3:243–59. https://doi.org/10.14283/jpad.2016.112.

Hampel H, O’Bryant SE, Durrleman S, Younesi E, Rojkova K, Escott-Price V, et al. A precision medicine initiative for Alzheimer’s disease: the road ahead to biomarker-guided integrative disease modeling. Climacteric. 2017;0:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/13697137.2017.1287866.

Hampel H, Toschi N, Babiloni C, Baldacci F, Black KL, Bokde ALW, et al. Revolution of Alzheimer precision neurology. Passageway of systems biology and neurophysiology. J Alzheimers Dis JAD. 2018;64:S47–105. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-179932.

Hampel H, Vergallo A, Perry G, Lista S. Alzheimer Precision Medicine Initiative (APMI). The Alzheimer Precision Medicine Initiative. J Alzheimers Dis JAD. 2019. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-181121.

Habert M-O, Bertin H, Labit M, Diallo M, Marie S, Martineau K, et al. Evaluation of amyloid status in a cohort of elderly individuals with memory complaints: validation of the method of quantification and determination of positivity thresholds. Ann Nucl Med. 2018;32:75–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12149-017-1221-0.

Schwarz CG, Senjem ML, Gunter JL, Tosakulwong N, Weigand SD, Kemp BJ, et al. Optimizing PiB-PET SUVR change-over-time measurement by a large-scale analysis of longitudinal reliability, plausibility, separability, and correlation with MMSE. NeuroImage. 2017;144:113–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.08.056.

Hampel H, Toschi N, Baldacci F, Zetterberg H, Blennow K, Kilimann I, et al. Alzheimer’s disease biomarker-guided diagnostic workflow using the added value of six combined cerebrospinal fluid candidates: Aβ1-42, total-tau, phosphorylated-tau, NFL, neurogranin, and YKL-40. Alzheimers Dement J Alzheimers Assoc. 2018;14:492–501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2017.11.015.

Baldacci F, Toschi N, Lista S, Zetterberg H, Blennow K, Kilimann I, et al. Two-level diagnostic classification using cerebrospinal fluid YKL-40 in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement J Alzheimers Assoc. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2017.01.021.

Olsson B, Lautner R, Andreasson U, Öhrfelt A, Portelius E, Bjerke M, et al. CSF and blood biomarkers for the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(16)00070-3.

Ashton NJ, Leuzy A, Lim YM, Troakes C, Hortobágyi T, Höglund K, et al. Increased plasma neurofilament light chain concentration correlates with severity of post-mortem neurofibrillary tangle pathology and neurodegeneration. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2019;7:5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40478-018-0649-3.

Palmqvist S, Insel PS, Zetterberg H, Blennow K, Brix B, Stomrud E, et al. Accurate risk estimation of β-amyloid positivity to identify prodromal Alzheimer’s disease: cross-validation study of practical algorithms. Alzheimers Dement. 2019;15:194–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2018.08.014.

Randall J, Mörtberg E, Provuncher GK, et al. Tau proteins in serum predict neurological outcome after hypoxic brain injury from cardiac arrest: results of a pilot study. Resuscitation. 2013;84(3):351–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.07.027.

Gisslén M, Price RW, Andreasson U, et al. Plasma concentration of the Neurofilament light protein (NFL) is a biomarker of CNS injury in HIV infection: a cross-sectional study. EBioMedicine. 2015;3:135–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2015.11.036.

Applied Mixed Models in Medicine, 2nd Edition. WileyCom n.d. https://www.wiley.com/en-us/Applied+Mixed+Models+in+Medicine%2C+2nd+Edition-p-9780470023563. Accessed 19 Feb 2019.

Abdi H, Williams LJ. Partial least squares methods: partial least squares correlation and partial least square regression. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;930:549–79. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-62703-059-5_23.

Barker M, Rayens W. Partial least squares for discrimination. J Chemom. 2003;17:166–73. https://doi.org/10.1002/cem.785.

Sundermann EE, Panizzon MS, Chen X, et al. Sex differences in Alzheimer’s-related tau biomarkers and a mediating effect of testosterone. Biol Sex Differ. 2020;11:33. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13293-020-00310-x.

Alzheimer Association. 2016 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2016;12(4):459–509. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2016.03.001.

Hansson O, Janelidze S, Hall S, Magdalinou N, Lees AJ, Andreasson U, et al. Blood-based NfL: a biomarker for differential diagnosis of parkinsonian disorder. Neurology. 2017;88:930–7. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000003680.

Bridel C, van Wieringen WN, Zetterberg H, et al. Diagnostic value of cerebrospinal fluid neurofilament light protein in neurology: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76(9):1035–48. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.1534.

Gaetani L, Blennow K, Calabresi P, Di Filippo M, Parnetti L, Zetterberg H. Neurofilament light chain as a biomarker in neurological disorders. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2018-320106.

Palermo G, Mazzucchi S, Della Vecchia A, et al. Different clinical contexts of use of blood neurofilament light chain protein in the spectrum of neurodegenerative diseases [published online ahead of print, 2020 Aug 9]. Mol Neurobiol. 2020;10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12035-020-02035-9.

Vågberg M, Norgren N, Dring A, Lindqvist T, Birgander R, Zetterberg H, et al. Levels and age dependency of neurofilament light and glial Fibrillary acidic protein in healthy individuals and their relation to the brain parenchymal fraction. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0135886. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0135886.

Greicius MD, Krasnow B, Reiss AL, Menon V. Functional connectivity in the resting brain: a network analysis of the default mode hypothesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:253–8. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0135058100.

Chiesa PA, Cavedo E, Vergallo A, Lista S, Potier M-C, Habert M-O, et al. Differential default mode network trajectories in asymptomatic individuals at risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement J Alzheimers Assoc. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2019.03.006.

Lewczuk P, Ermann N, Andreasson U, Schultheis C, Podhorna J, Spitzer P, et al. Plasma neurofilament light as a potential biomarker of neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2018;10:71. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-018-0404-9.

Baldacci F, Mazzucchi S, Della Vecchia A, Giampietri L, Giannini N, Koronyo-Hamaoui M, et al. The path to biomarker-based diagnostic criteria for the spectrum of neurodegenerative diseases. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2020;20:421–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/14737159.2020.1731306.

Preische O, Schultz SA, Apel A, Kuhle J, Kaeser SA, Barro C, et al. Serum neurofilament dynamics predicts neurodegeneration and clinical progression in presymptomatic Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Med. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-018-0304-3.

Weston PSJ, Poole T, Ryan NS, Nair A, Liang Y, Macpherson K, et al. Serum neurofilament light in familial Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2017;89:2167–75. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000004667.

Baldacci F, Lista S, Vergallo A, Palermo G, Giorgi FS, Hampel H. A frontline defense against neurodegenerative diseases:the development of early disease detection methods. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2019;19:559–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/14737159.2019.1627202.

Penner G, Lecocq S, Chopin A, Vedoya X, Lista S, Vergallo A, et al. Blood-based diagnostics of Alzheimer’s disease. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2019;19:613–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/14737159.2019.1626719.

Acknowledgements

INSIGHT-preAD Study Group:

Hovagim Bakardjian, Habib Benali, Hugo Bertin, Joel Bonheur, Laurie Boukadida, Nadia Boukerrou, Enrica Cavedo, Patrizia Chiesa, Olivier Colliot, Bruno Dubois, Marion Dubois, Stéphane Epelbaum, Geoffroy Gagliardi, Remy Genthon, Marie-Odile Habert, Harald Hampel, Marion Houot, Aurélie Kas, Foudil Lamari, Marcel Levy, Simone Lista, Christiane Metzinger, Fanny Mochel, Francis Nyasse, Catherine Poisson, Marie-Claude Potier, Marie Revillon, Antonio Santos, Katia Santos Andrade, Marine Sole, Mohmed Surtee, Michel Thiebaut de Schotten, Andrea Vergallo, Nadjia Younsi.

AV is an employee of Eisai Inc. This work has been performed during his previous position at Sorbonne University, Paris, France.

HH is an employee of Eisai Inc. This work has been performed during his previous position at Sorbonne University, Paris, France. At Sorbonne University, he was supported by the AXA Research Fund, the “Fondation partenariale Sorbonne Université”, and the “Fondation pour la Recherche sur Alzheimer”, Paris, France.

Contributors to the Alzheimer Precision Medicine Initiative – Working Group (APMI–WG):

Mohammad AFSHAR (France), Lisi Flores AGUILAR (Canada), Leyla AKMAN-ANDERSON (USA), Joaquín ARENAS (Spain), Jesús ÁVILA (Spain), Claudio BABILONI (Italy), Filippo BALDACCI (Italy), Richard BATRLA (Switzerland), Norbert BENDA (Germany), Keith L. BLACK (USA), Arun L.W. BOKDE (Ireland), Ubaldo BONUCCELLI (Italy), Karl BROICH (Germany), Francesco CACCIOLA (Italy), Filippo CARACI (Italy), Giuseppe CARUSO (Italy), Juan CASTRILLO† (Spain), Enrica CAVEDO (France), Roberto CERAVOLO (Italy), Patrizia A. CHIESA (France), Massimo CORBO (Italy), Jean-Christophe CORVOL (France), Augusto Claudio CUELLO (Canada), Jeffrey L. CUMMINGS (USA), Herman DEPYPERE (Belgium), Bruno DUBOIS (France), Andrea DUGGENTO (Italy), Enzo EMANUELE (Italy), Valentina ESCOTT-PRICE (UK), Howard FEDEROFF (USA), Maria Teresa FERRETTI (Switzerland), Massimo FIANDACA (USA), Richard A. FRANK (USA), Francesco GARACI (Italy), Hugo GEERTS (USA), Ezio GIACOBINI (Switzerland), Filippo S. GIORGI (Italy), Edward J. GOETZL (USA), Manuela GRAZIANI (Italy), Marion HABERKAMP (Germany), Marie-Odile HABERT (France), Britta HÄNISCH (Germany), Harald HAMPEL (France), Karl HERHOLZ (UK), Felix HERNANDEZ (Spain), Bruno P. IMBIMBO (Italy), Dimitrios KAPOGIANNIS (USA), Eric KARRAN (USA), Steven J. KIDDLE (UK), Seung H. KIM (South Korea), Yosef KORONYO (USA), Maya KORONYO-HAMAOUI (USA), Todd LANGEVIN (USA), Stéphane LEHÉRICY (France), Pablo LEMERCIER (France), Simone LISTA (France), Francisco LLAVERO (Spain), Jean LORENCEAU (France), Alejandro LUCÍA (Spain), Dalila MANGO (Italy), Mark MAPSTONE (USA), Christian NERI (France), Robert NISTICÒ (Italy), Sid E. O’BRYANT (USA), Giovanni PALERMO (Italy), George PERRY (USA), Craig RITCHIE (Scotland), Simone ROSSI (Italy), Amira SAIDI (Italy), Emiliano SANTARNECCHI (USA), Lon S. SCHNEIDER (USA), Olaf SPORNS (USA), Nicola TOSCHI (Italy), Pedro L. VALENZUELA (Spain), Bruno VELLAS (France) Steven R. VERDOONER (USA), Andrea VERGALLO (France), Nicolas VILLAIN (France), Kelly VIRECOULON GIUDICI (France), Mark WATLING (UK), Lindsay A. WELIKOVITCH (Canada), Janet WOODCOCK (USA), Erfan YOUNESI (France), José L. ZUGAZA (Spain).

Funding

The research and this manuscript was part of the translational research program “PHOENIX,” awarded to HH, and administered by the Sorbonne University Foundation and sponsored by la Fondation pour la Recherche sur Alzheimer.

The study was promoted by INSERM in collaboration with ICM, IHU-A-ICM, and Pfizer and has received support within the “Investissement d’Avenir” (ANR-10-AIHU-06) French program. The study was promoted in collaboration with the “CHU de Bordeaux” (coordination CIC EC7), the promoter of Memento cohort, funded by the Foundation Plan-Alzheimer. The study was further supported by AVID/Lilly.

CATI is a French neuroimaging platform funded by the French Plan Alzheimer (available at http://cati-neuroimaging.com).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

Filippo Baldacci designed and conceptualized the study, interpreted the data, and drafted the manuscript for intellectual content. Simone Lista designed and conceptualized the study, interpreted the data, and revised the manuscript for intellectual content. Maria L. Manca interpreted the data, analyzed the data, and revised the manuscript for intellectual content.

Patrizia A. Chiesa interpreted the data and revised the manuscript for intellectual content. Enrica Cavedo interpreted the data and revised the manuscript for intellectual content. Pablo Lemercier interpreted the data and analyzed the data. Henrik Zetterberg had a major role in the acquisition of data. Kaj Blennow had a major role in the acquisition of data. Marie-Odile Habert had a major role in the acquisition of data. Marie Claude Potier had a major role in the acquisition of data. Bruno Dubois designed and conceptualized the study. Andrea Vergallo analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript for intellectual content. Harald Hampel designed and conceptualized the study and drafted the manuscript for intellectual content. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the institutional review boards of all participating institutions, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants or their guardians according to the Declaration of Helsinki (consent for research).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

SL received lecture honoraria from Roche and Servier.

AV is an employee of Eisai Inc. He does not receive any fees or honoraria since November 2019. Before November 2019 he had received lecture honoraria from Roche, MagQu LLC, and Servier.

HH is an employee of Eisai Inc. and serves as Senior Associate Editor for the Journal Alzheimer’s & Dementia and does not receive any fees or honoraria since May 2019; before May 2019, he had received lecture fees from Servier, Biogen and Roche; research grants from Pfizer, Avid, and MSD Avenir (paid to the institution); travel funding from Functional Neuromodulation, Axovant, Eli Lilly and company, Takeda and Zinfandel, GE-Healthcare and Oryzon Genomics; consultancy fees from Qynapse, Jung Diagnostics, Cytox Ltd., Axovant, Anavex, Takeda and Zinfandel, GE Healthcare and Oryzon Genomics, and Functional Neuromodulation; and participated in scientific advisory boards of Functional Neuromodulation, Axovant, Eisai, Eli Lilly and company, Cytox Ltd., GE Healthcare, Takeda and Zinfandel, Oryzon Genomics and Roche Diagnostics.

He is co-inventor in the following patents as a scientific expert and has received no royalties:

• In Vitro Multiparameter Determination Method for The Diagnosis and Early Diagnosis of Neurodegenerative Disorders Patent Number: 8916388.

• In Vitro Procedure for Diagnosis and Early Diagnosis of Neurodegenerative Diseases Patent Number: 8298784.

• Neurodegenerative Markers for Psychiatric Conditions Publication Number: 20120196300.

• In Vitro Multiparameter Determination Method for The Diagnosis and Early Diagnosis of Neurodegenerative Disorders Publication Number: 20100062463.

• In Vitro Method for The Diagnosis and Early Diagnosis of Neurodegenerative Disorders Publication Number: 20100035286.

• In Vitro Procedure for Diagnosis and Early Diagnosis of Neurodegenerative Diseases Publication Number: 20090263822.

• In Vitro Method for The Diagnosis of Neurodegenerative Diseases Patent Number: 7547553.

• CSF Diagnostic in Vitro Method for Diagnosis of Dementias and Neuroinflammatory Diseases Publication Number: 20080206797.

• In Vitro Method for The Diagnosis of Neurodegenerative Diseases Publication Number: 20080199966.

• Neurodegenerative Markers for Psychiatric Conditions Publication Number: 20080131921.

HZ is a Wallenberg Academy Fellow supported by grants from the Swedish Research Council, the European Research Council, Swedish State Support for Clinical Research (ALFGBG), and the UK Dementia Research Institute at UCL.

KB holds the Torsten Söderberg Professorship in Medicine at the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences and is supported by the Swedish Research Council (#2017-00915), the Swedish Alzheimer Foundation (#AF-742881), Hjärnfonden, Sweden (#FO2017-0243), and a grant (#ALFGBG-715986) from the Swedish state under the agreement between the Swedish government and the County Councils, the ALF-agreement.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:

Table 1S. Demographic, clinical and biomarkers description of the progressive SMC (N = 6) at follow-up. Abbreviations: MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination score; FCSRT, Free and Cued Selective Rating Test; NFL, neurofilament light chain; t-Tau, total Tau.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Baldacci, F., Lista, S., Manca, M.L. et al. Age and sex impact plasma NFL and t-Tau trajectories in individuals with subjective memory complaints: a 3-year follow-up study. Alz Res Therapy 12, 147 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-020-00704-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-020-00704-4