Abstract

Background

Patients with unprovoked first venous thromboembolism (VTE) are at a high risk of recurrence. Although circulating microRNAs (miRNAs) have been found to be associated with VTE and are markers of hypercoagulability, this study is the first to examine whether circulating miRNAs are associated with the risk of VTE recurrence.

Results

A nested case-control study design was used where plasma samples were obtained from 78 patients with unprovoked VTE from the Malmö Thrombophilia Study (MATS). A total of 39 VTE patients with recurrent VTE (cases) were matched with 39 VTE patients without recurrent VTE (controls) defined by age and sex (MATS population). Plasma levels of 179 different miRNAs were evaluated in the 78 samples (after anticoagulant treatment was stopped) using qPCR. A total of 110 miRNAs were detected in all samples. Among those, 12 miRNAs (miR-15b-5p, miR-106a-5p, miR-197-3p, miR-652-3p, miR-361-5p, miR-222-3p, miR-26b-5p, miR-532-5p, miR-27b-3p, miR-21-5p, miR-103a-3p, and miR-30c-5p) were found to be associated with recurrent VTE after multiple correction test and conditional logistic regression analysis. A further analysis showed that miR-15b-5p, miR-197-3p, miR-27b-3p, and miR-30c-5p exhibited a trend over time, with a larger difference in miRNA levels between cases and controls for earlier recurrence. Of these 12 miRNAs, 8 miRNAs significantly correlated with circulating transforming growth factor β1/2 (TGFβ1/2). Three of them correlated with platelet count.

Conclusion

We have identified 12 plasma miRNAs that may have the potential to serve as novel, non-invasive predictive biomarkers for VTE recurrence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is the third most common cardiovascular disease with an estimated annual incidence rate of 100–200 events per 100,000 individuals [1,2,3]. The most severe manifestation of VTE is fatal pulmonary embolism (PE) with an annual incidence rate of 2–4 events per 100,000 individuals [4]. VTE is a chronic disease with a recurrence risk of up to 20% within 3 years [5]. Recurrent VTE can be fatal in 10–20% of cases [6]. Patients with an unprovoked VTE (without an identified major clinical risk factor such as recent surgery or trauma, female hormone therapy or pregnancy, or malignancies) have a higher risk of recurrence after discontinuation of anticoagulation treatment compared with those patients with a provoked VTE [5, 7]. Long-term anticoagulation treatment, after the initial VTE, may prevent the recurrence but extended anticoagulation treatment may increase the risk of bleeding complications including fatal intracranial hemorrhage [6, 8]. Therefore, it is important to identify the patients, with a high risk of recurrence, who would benefit most from continuous anticoagulant treatment. There are a number of identified risk factors related to recurrent VTE, such as unprovoked VTE, elevated D-dimer levels, male gender, obesity, thrombophilia, and family history of VTE [9,10,11,12,13]. There is now a consensus regarding the optimal duration of anticoagulation treatment after an unprovoked VTE event. The treatment choice is between a short duration of 3–6 months and an extended duration. Clinical prediction rules have been developed to aid in this choice but the ability of such rules to predict bleeding appears to be low [14, 15]. Thus, better novel biomarkers for prediction of recurrent VTE risk could be of value.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are short, endogenous, and non-coding single-stranded RNAs that inhibit gene expression by promoting messenger-RNA (mRNA) degradation or inhibiting translation [16]. miRNAs have been shown to play essential roles in various biological processes during development and tissue homeostasis by regulating the expression of approximately 90% of all human genes [17]. The majority of miRNAs are expressed intracellularly. However, numerous miRNAs have been detected in the extracellular space, including blood and other body fluids [18]. Circulating miRNAs can be secreted from cells into the blood in different ways, e.g., enclosed in exosomes or associated with proteins [19, 20]. They are resistant to nuclease digestion and can be measured reproducibly, which makes circulating miRNAs attractive as potential biomarkers for diseases. Over the past decade, circulating miRNAs, as potential biomarkers, have been documented in many diseases such as cancer, psychiatric diseases, diabetes mellitus, and heart failure [21,22,23,24,25]. However, there is only limited evidence on potentially altered circulating miRNA levels in VTE. To our knowledge, only a few studies have investigated the association between circulating miRNAs and unprovoked VTE [25,26,27,28,29]. Wang et al. found that miR-424-5p is increased in patients with acute venous thrombosis and that it is correlated with a marker of hypercoagulability (D-dimer and APC-PCI complex) [25]. Thus far, however, no results regarding miRNA expression in recurrent VTE patients have been reported.

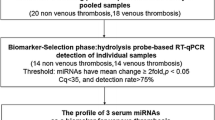

The present study used data from a prospective population-based study conducted in the south of Sweden; Malmö Thrombophilia Study (MATS) [30, 31]. In this study, the expression of plasma miRNAs was measured in 39 patients with recurrent VTE (cases) and 39 with non-recurrent VTE (controls) 2 weeks after discontinuation of anticoagulation. We hypothesized that specific miRNAs expression profile could be used to distinguish patients at high and low risk of recurrence. Therefore, our aim was to investigate the association between circulating miRNAs and the risk of VTE recurrence.

Results

Patients’ characteristics

Baseline characteristics of the 78 participants are shown in Table 1. Cases were those who were diagnosed with recurrent VTE during the follow-up period, whereas controls were those without recurrent VTE. The mean age was 65.3 years for cases and 65.1 years for controls. A total of 67% of the participants with recurrent VTE had thrombophilia compared with 41% of the participants without recurrent VTE (p = 0.09). There was no significant difference between the two groups in body mass index (BMI), duration of anticoagulant treatment, smoking status, and family history, which was defined as a history of VTE in first-degree relatives (sibling, son/daughter, or parent).

miRNAs screening data

A total of 179 miRNAs were analyzed in all 78 samples. Additional file 1: Figure S1 shows the sample quality control using spike-ins, UniSp2/UniSp4/UniSp5/ UniSp6, and UniSp3 (technical controls). The steady level of these assays shown in the graphs indicates that extraction, reverse transcription, and qPCR were successful. In addition, no hemolysis samples were present in the study population as measured by the ratio of miR-451a to miR-23a-3p. Of the 179 miRNAs analyzed in all 78 samples, an average of 150 miRNAs were detectable in more than 90% of the samples, and 110 miRNAs were detected in all samples.

miRNAs profiling association with VTE recurrence

After further analysis of these 110 miRNAs (as shown in Additional file 2: Table S1), we found that 14 miRNAs were expressed in all samples and were significantly different (after adjusting for multiple testing using Benjamini-Hochberg correction with a false discovery rate (FDR) of 25%) [32] between cases and controls (presented in Table 2): miR-15b-5p, miR-106a-5p, miR-197-3p, miR-652-3p, miR-361-5p, miR-222-3p, miR-26b-5p, miR-532-5p, miR-27b-3p, miR-21-5p, miR-103a-3p, miR-30c-5p, miR-146b-5p, and miR-22-3p. Of these 14 differentially expressed miRNAs, miR-15b-5p, miR-222-3p, miR-26b-5p, miR-532-5p, miR-21-5p, miR-30c-5p, miR-146b-5p, and miR-22-3p were increased in cases compared to controls, whereas miR-106a-5p, miR-197-3p, miR-652-3p, miR-361-5p, miR-27b-3p, and miR-103a-3p were decreased (Additional file 1: Figure S2).

To investigate the association between circulating miRNAs and the risk of VTE recurrence, we performed conditional logistic regression analysis on the 14 miRNAs displayed in Table 2. Twelve of the 14 miRNAs were significantly associated with the risk of VTE recurrence (Table 3). Two miRNAs, miR-146b-5p and miR-22-3p, were not significantly associated with recurrent VTE. The odds of having recurrent VTE were increased (OR > 1) for a one standard deviation (SD) increment in miRNA levels for miR-15b-5p, miR-222-3p, miR-26b-5p, miR-532-5p, miR-21-5p, and miR-30c-5p. By contrast, the odds decreased (OR < 1) for miR-106a-5p, miR-197-3p, miR-652-3p, miR-361-5p, miR-27b-3p, and miR-103a-3p (Table 3). The highest OR was for miR-15b-5p (OR = 7.8).

We further analyzed the expression levels of the 12 most significant miRNAs regarding time to recurrent VTE during follow-up. As shown in Fig. 1, the following miRNAs, miR-15b-5p, miR-197-3p, miR-27b-3p, and miR-30c-5p exhibited a trend over time, with larger difference in miRNA levels between cases and controls for earlier recurrence (Ptrend < 0.05). The other miRNAs showed no significant pattern of this time-dependency (data not shown).

In silico search for miRNA target genes and biological pathways

In order to further investigate the pathophysiological roles of miRNAs in VTE recurrence, we performed an in silico search to identify putative targets and pathways. We found that these miRNAs potentially regulated important genes, such as the human genes encoding for vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), metalloproteases, cytokines, and protein kinases (MAPK) that participate in the regulation of activation of monocytes, platelets, and endothelial cells (Table 4).

We then used the DAVID annotation tool for the pathway analysis (DAVID 6.8, https://david.ncifcrf.gov/), and the most important pathways potentially involved in VTE pathophysiology are listed in Table 5, such as phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-protein kinase B (PI3Ks-Akt), mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), TGF-beta, Hippo signaling pathway, and hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF). The full list of biological pathways potentially regulated by these miRNAs is shown in Additional file 3: Table S2.

Correlation of miRNAs associated with recurrent VTE and TGFβ1/2/3 and plasma clot parameters

We previously reported that there was an association between higher risks of recurrent VTE and lower levels of plasma TGFβ1/2 [31]. In the present study, we found that there were correlations between TGFβ1 and most of the significant miRNAs (Table 6). The expression of miR-15b-5p, miR-106a-5p, miR-197-3p, miR-652-3p, miR-361-5p, miR-27b-3p, and miR-103a-3p were positively correlated with TGFβ1 expression, whereas miR-532-5p was negatively correlated. Similar results were also found for TGFβ2, but only miR-15b-5p, miR-197-3p, and miR-27b-3p correlated with TGFβ3 (data not shown). Thus, a total of 8 out of 12 miRNAs were correlated with TGFβ1/2 expression.

Platelet count was positively correlated with the expression of plasma miR-652-3p (r = 0.31, p = 0.006). In addition, miR-197-3p (r = 0.23, p = 0.05) and miR-27b-3p (R = 0.21, p = 0.066) were also positively correlated with platelet count, but the correlations were not statistically significant. Some of these 12 identified miRNAs were also correlated with plasma clot parameters: miR-15b-5p (r = 0.34, p = 0.003), miR-652-3p (r = 0.26, p = 0.02), and miR-103a-3p (r = 0.32, p = 0.005) were positively correlated with the international normalized ratio (INR) and miR-26b-5p was negatively correlated with both protein C and protein S (Additional file 4: Table S3).

The potential role of these miRNAs in primary VTE

We also checked whether the 12 miRNAs profile associated with recurrent VTE identified in the present study was also associated with primary VTE in the SCORE cohort. None of these miRNAs were significantly associated with primary VTE (data not shown).

Discussion

As far as we know, this is the first study to explore the association of circulating miRNAs and the risk of VTE recurrence. We found that expression of miR-15b-5p, miR-106a-5p, miR-197-3p, miR-652-3p, miR-361-5p, miR-222-3p, miR-26b-5p, miR-532-5p, miR-27b-3p, miR-21-5p, miR-103a-3p, and miR-30c-5p were significantly different between cases (recurrent VTE) and controls (non-recurrent). High plasma levels of miR-15b-5p, miR-222-3p, miR-26b-5p, miR-532-5p, miR-21-5p, and miR-30c-5p and lower levels of miR-106a-5p, miR-197-3p, miR-652-3p, miR-361-5p, miR-27b-3p, and miR-103a-3p were significantly associated with risk of VTE recurrence. Moreover, miR-15b-5p, miR-197-3p, miR-27b-3p, and miR-30c-5p exhibited a trend over time, with a larger difference in miRNA levels between cases and controls for earlier recurrence. In addition, we found that some of the miRNAs were correlated with plasma TGFβ levels, platelet count, and plasma clot properties.

In particular, among patients with unprovoked VTE, identifying patients who are at highest risk for recurrent VTE is a clinically important issue. At present, a few biomarkers such as D-dimer and endogenous thrombin potential (ETP), circulating P-selectin, plasma TGFβ levels, and plasma clot properties have been suggested to identify VTE patients that are at risk of VTE recurrence [31, 33,34,35,36]. However, it still remains a challenge to predict individuals at risk of VTE recurrence [37]. The present study shows that miRNAs are a novel group of biomarkers that are potentially useful for predicting the risk of VTE recurrence.

By performing an in silico search for miRNA target genes and pathway enrichment analysis, we found, as expected, that miRNAs could regulate different genes and are involved in different pathways. However, the most important pathways, which could have a role in the pathophysiology of VTE, are discussed here; MAPK signaling pathways have been previously shown to be involved in the pathophysiology of thrombosis or platelet activity in a direct or indirect manner [31, 38,39,40,41,42]. Similarly, the Hippo signaling pathway has been shown to play an important role in megakaryocyte differentiation and platelet production [41, 43]. HIF-1 pathway is known to promote endothelial permeability and activation, coagulopathy, and recruitment of inflammatory cells, and contribute to the initiation or development of venous thrombosis through its target genes [42]. In each pathway, the function of miRNAs overlaps with each other. For example, all the 12 identified miRNAs involved in the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, which could regulate platelet activation in thrombus formation and stabilization [40]. These analyses further illustrated the possible roles and mechanisms of these differentially expressed miRNAs in VTE.

Our previous study concerning VTE recurrence showed that lower plasma levels of TGFβ1/2 were significantly associated with higher risks of recurrent VTE [31]. In the present study, we found that plasma levels of miR-15b-5p, miR-106a-5p, miR-197-3p, miR-652-3p, miR-361-5p, miR-27b-3p, and miR-103a-3p were positively correlated with TGFβ1/2 expression, whereas miR-532-5p were negatively correlated. The miR-15 family was identified as a novel regulator of cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis acting by inhibiting the TGFβ-pathway [44]. MiR-27b and miR-532 were also demonstrated to be involved directly or indirectly in the TGFβ pathway in animal experiments [45, 46]. Based on these observations, it is possible that the role of these miRNAs in VTE recurrence may also be TGFβ-pathway-dependent. However, this needs to be investigated in future studies.

Another important finding of this study is that miRNAs were correlated with plasma clot properties. For example, miR-15b-5p, miR-652-3p, and miR-103a-3p were positively correlated with the INR while plasma miR-197-3p, miR-27b-3p, and miR-652-3p were correlated with platelet count. Nordstrom et al. found that subtherapeutic INR levels were associated with a more than threefold increased risk of VTE recurrence and low platelet counts also predicted a greater risk of VTE recurrence [47].

There are important differences in risk factor profiles between primary and recurrent VTE [48]. Therefore, we tested these 12 miRNAs in a primary VTE population—the SCORE study [25]. However, none of these miRNAs were significantly associated with primary VTE [28]. As VTE encompasses both DVT and PE, the different miRNA expression profiles between these studies could be related to the differences in the subsets of selected patient cohorts or duration after initial thrombotic event. Therefore, the results from the present study do not allow us to conclude that miRNAs identified in recurrent VTE were not related to primary VTE. However, our finding of different miRNA profile for primary and recurrent VTE is in line with a large number of studies that have shown that the risk factor profile is different between primary and recurrent VTE, as reviewed by Cannegieter and Van Hylckama Vlieg [48]. Thus, different miRNAs may play a different role in primary and recurrent VTE. A validation study therefore is warranted due to the high variation between studies.

Recent studies have suggested that arterial and venous thrombosis share common risk factors [49,50,51]. In the present study, we found that high levels of plasma miR-15b-5p, miR-222-3p, miR-26b-5p, miR-532-5p, miR-21-5p, and miR-30c-5p were significantly associated with a higher risk of VTE recurrence. Most of these miRNAs have been involved in other cardiovascular diseases. Tijsen et al. found that the miR-15 family (miR-15a/b, miR-16, miR-195, miR-497, and miR-322) is upregulated in cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure. Higher plasma levels of miR-21-5p were significantly associated with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) patients [52]. miR-222 has been reported to play an important role in physiological and pathological processes in the heart and may be a potential cardiovascular biomarker and a new therapeutic target in cardiovascular diseases [53]. Circulating miR-26b-5p and 30c-5p were also related to heart failure [54, 55]. In our analysis, low levels of miR-106a-5p, miR-197-3p and miR-652-3p, miR-361-5p, miR-27b-3p, and miR-103a-3p were associated with higher risk of VTE recurrence. Previous studies reported that low levels of miR-106a-5p and miR-197-3p were associated with a high risk of AMI [56, 57] and low levels of miR-106a-5p, miR-103, miR-361-5p, miR-27b-3p, and miR-652-3p were related to acute heart failure [54, 58,59,60,61]. Put together, there may be some specific miRNAs generally associated with both arterial and venous thrombosis.

This is a hypothesis-generating study in which, for the first time, the role of circulating miRNAs in VTE recurrence has been studied. Our findings require an independent validation study. There are several general limitations in our experimental design that should be considered when interpreting our results. The main limitation of the study is the relatively small number of patients. Although we adjusted the results for multiple comparisons, we found several microRNAs related to recurrent VTE. A potential mechanistic limitation is that the cellular origin of these miRNAs could not be determined. Therefore, we are unable to detect the mechanism behind the changes of these miRNAs.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that platelets and the TGFβ pathways regulating miRNAs may serve as novel biomarkers for VTE recurrence. The present study warrants further investigation on the role of miRNAs in recurrent VTE.

Material and methods

Study design and subjects

The present study used a nested case-control design, including selected subjects from a pre-existed cohort that has been followed over time. The subjects were selected from a prospective population-based cohort study at Skåne University Hospital in Sweden; Malmö Thrombophilia Study (MATS). MATS included a total of 1465 consecutive patients diagnosed with VTE between March 1998 and December 2008 [30]. The inclusion criteria in MATS were the following: age > 18, ability to speak and read Swedish, and an objective diagnosis of DVT or PE made with phlebography, duplex ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), lung scintigraphy, or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [30]. The following information was recorded: location of DVT, immobilization and cast therapy, hospitalization, surgical intervention, malignancies that were diagnosed previously or at diagnosis of VTE, use of contraceptive pills, hormonal therapy, pregnancy and postpartum period (first 6 weeks after delivery), family history of VTE (history of VTE in first-degree relatives), VTE recurrence during the follow-up period (until the end of the study in December 2008), and other risk factors, such as tobacco use or traveling information. A research nurse was responsible for screening the hospital records of patients. All VTE cases and recurrent events were objectively confirmed in this well-characterized population-based study. The participation rate was high (70%). The remaining 30% of patients did not participate in blood sampling, questionnaire, and complete risk factor analysis because of language problems, dementia, or other severe diseases [30].

According to the standard treatment protocol of Skåne University Hospital, all VTE patients were treated with low-molecular-weight heparin or unfractionated heparin during the initiation of oral anticoagulants (OAC, Warfarin). The treatment protocol recommended that 3–6 months OAC therapy for first-time VTE and consideration of longer-term therapy for recurrent VTE.

Thrombophilia was defined as presence of the factor V Leiden (FVL) mutation (rs6025) or factor II G20210A mutation (rs1799963), or a level below the laboratory reference range of protein C [< 0.7 k international unit (kIU/L)], free protein S (women < 0.5 kIU/L, men < 0.65 kIU/L) or antithrombin (< 0.82 kIU/L) in patients without warfarin treatment.

A total of 78 patients (26–85 years) with unprovoked VTE were recruited from MATS. Unprovoked VTE was defined as complete absence of provoking factors at the time of diagnosis. The following were regarded as provoking factors: malignancies, surgical intervention, use of contraceptive pills or hormonal therapy, pregnancy or puerperium, acute medical conditions (AMI, acute ischemic stroke, major infectious disease), and marked immobilization (bed rest > 3 days, patients in a wheelchair, long-distance travel ≥ 4 h within the last 14 days). Patients who had any of these provoking factors were excluded from the study (n = 283). Besides these exclusions, patients who had thrombotic events before inclusion (n = 25), or recurrence during anticoagulant therapy (n = 281), those who gave post-treatment samples during treatment (n = 382) and those who had inadequate or missing case report forms were also excluded (n = 51). Among the remaining 443 patients with unprovoked VTE, 41 suffered from recurrent VTE. Two plasma samples were excluded due to poor plasma quality (e.g., hemolysis). In total, 39 patients with recurrent VTE (cases) and 39 age-, sex-, and time of sampling matched patients from the MATS study population without recurrent VTE (controls) during the follow-up period were included in the present study.

The primary VTE cohort consisted of 238 (aged 16–95 years, 91 men and 147 women) plasma samples, 51 DVT patients and 183 patients without DVT (4 samples were excluded due to the low sample volume), selected from a prospective multicenter diagnostic management study (SCORE) [25].

Sample preparation

The blood samples were taken 2 weeks after discontinuing oral anticoagulant therapy given to the patients with a first thrombotic event. Venous blood samples were collected into sodium citrate (3.8%)-treated tubes and were centrifuged at 2000×g for 15 min at 4 °C to obtain platelet-poor plasma. Samples were transferred to new RNase/DNase-free tubes and then were centrifuged again at 3000×g, 10 min at 4 °C to obtain platelet-poor plasma, the plasma was then aliquoted and stored at − 80 °C before further processing.

Circulating miRNA exploration

Total RNA was isolated from 230 μl of plasma using the Qiagen miRNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, with minor modifications. miRNAs were reverse transcribed using a Universal cDNA Synthesis kit (Exiqon, Vedbæk, Denmark). The resulting reverse transcription reaction product was stored at − 20 °C for further analysis. A detailed description of the methodology has been provided in previous articles [24, 62]. It is important for any types of qPCR experiments to ensure that the quality of the input RNA is sufficiently high for effective amplification. We used spike-in RNAs in all steps of our experiments, i.e., in the RNA extraction, the cDNA synthesis. RNA spike-in kit (Exiqon, Vedbæk, Denmark) for quality control of the RNA isolation (UniSp2/UniSp4/UniSp5) and cDNA synthesis (UniSp6) was applied.

For the initial screening, miRNA expression was screened using a Serum/Plasma Focus microRNA PCR Panel (Exiqon) comprising 179 LNA™ microRNA primer sets focusing on serum/plasma-relevant human miRNAs. A negative control without template from the reverse transcription reaction was included in the analyses. Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) was conducted using a CFX384 Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad). The panels contain assays for synthetic RNA (UniSp2/UniSp4//UniSp5/ UniSp6) in the RNA spike-in kit for controlling the RNA isolation and cDNA synthesis. In addition, an inter-plate control (UniSp3) was present in all panels. Two hemolysis miRNAs (miR-23a-3p, miR-451a) were also included in the panels. A hemolysis index, the ratio of miR-451a to miR-23a (ΔCt = Ct miR-23a-3p − Ct miR-451a) was used based on the qPCR detection according to a previous report [63]. Only the samples with ΔCT value < 7 were used in the following analysis. Undetectable data were assigned a default threshold cycle (Ct) value of 37. As there is no current consensus as to an appropriate reference miRNA for the normalization of plasma miRNAs in the qPCR analysis, we used the “global mean” as a reference in the analysis. The global mean is calculated as an average of all the detected assays in each sample. This means that the data set is not normalized to a “constant” but rather to the average expression for each sample. This normalization approach is used as a standard for big qPCR profiling projects [64]. We also normalized the 110 miRNAs with some endogenous miRNAs as normalizers. All the detected 110 miRNAs were compared and ranked using the currently available major computational programs (geNorm, Normfinder, BestKeeper, and the comparative ΔCt method) [65]. miR-423-5p, let-7i-5p, and miR-30e-5p were stable and abundant in the plasma, with a coefficient of variation of 1.8%, 2.0%, and 2.0% respectively. We therefore normalized 110 miRNAs with the geometric mean of miR-423-5p, let-7i-5p, and miR-30e-5p. The results were similar to that when using the global mean for normalization (data not shown). Ct values were then normalized to global mean using the following equation: ΔCt miR of interest = Ct global mean − Ct miR of interest. Relative expression of miRNAs was calculated with 2ΔCt. Fold changes were calculated as Fold change = 2ΔCt cases –ΔCt controls.

miRNAs target analysis

The analysis of miRNA-predicted targets was performed using three different algorithms (miRSystem, version 20120229; miRTarBase 7.0, and miRDB, version 4.0) available for free academic use [66,67,68]. The targeted genes, which have been validated by qPCR, western blot, or reporter assay, were summarized in a table as gene symbols (Table 4). The gene ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis of these target genes were then performed by DAVID Bioinformatics Resources 6.8 (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/) [29, 69].

Statistical analysis

Differences in sample characteristics between cases and controls were tested using Wilcoxon signed-rank test (for continuous variables) and conditional logistic regression (for the categorical variables).

To examine possible associations between miRNAs and recurrent VTE, we first tested the difference in ΔCt (Ctglobal mean − CtmiR of interest) of all 110 miRNAs between cases and controls using Wilcoxon signed-rank test (for three miRNAs a paired t test could be used instead because it was normally distributed). We adjusted for the false discovery rate using the Benjamini-Hochberg correction. False discovery rate was set at 0.25 (25% false positives are allowed). The association was also examined by graphing mean and 95% CI of fold changes (2ΔCt cases − ΔCt controls)).

Thereafter, we used conditional logistic regression on the significant miRNAs from the analysis above (scaled to have the same standard deviation) to examine the effect of miRNAs on the risk for recurrent VTE, as estimated by odds ratios. In addition, we examined if time to recurrent VTE was associated with miRNAs. We divided the time to recurrent VTE into categories with a similar number of cases (0–4 months, 4–12 months, > = 12 months). For those miRNAs that showed a significant trend in a regression model, we presented the median values of relative expression of miRNAs (2ΔCt) in a bar plot per time interval and for controls.

Spearman’s correlation or Pearson’s correlation analysis was applied to the significant miRNAs and TGFβ, platelets count, and plasma clot parameters. The difference of miRNAs expression levels between primary VTE and non-VTE was tested by t test.

STATA version 14 (StataCorp LP) was used for all statistical analyses.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- DVT:

-

Deep-vein thrombosis

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- miRNAs:

-

MicroRNAs

- PE:

-

Pulmonary embolism

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- TGFβ:

-

Transforming growth factor

- VTE:

-

Venous thromboembolism

References

Silverstein MD, Heit JA, Mohr DN, Petterson TM, O'Fallon WM, Melton LJ 3rd. Trends in the incidence of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a 25-year population-based study. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(6):585–93 Epub 1998/04/01. PubMed PMID: 9521222.

Naess IA, Christiansen SC, Romundstad P, Cannegieter SC, Rosendaal FR, Hammerstrom J. Incidence and mortality of venous thrombosis: a population-based study. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5(4):692–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02450.x PubMed PMID: 17367492. Epub 2007/03/21.

Goldhaber SZ, Bounameaux H. Pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis. Lancet. 2012;379(9828):1835–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(11)61904-1 PubMed PMID: 22494827. Epub 2012/04/13.

Shiraev TP, Omari A, Rushworth RL. Trends in pulmonary embolism morbidity and mortality in Australia. Thromb Res. 2013;132(1):19–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.thromres.2013.04.032 PubMed PMID: 23725850. Epub 2013/06/04.

Prandoni P, Noventa F, Ghirarduzzi A, Pengo V, Bernardi E, Pesavento R, et al. The risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism after discontinuing anticoagulation in patients with acute proximal deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism. A prospective cohort study in 1,626 patients. Haematologica. 2007;92(2):199–205 Epub 2007/02/14. PubMed PMID: 17296569.

Carrier M, Le Gal G, Wells PS, Rodger MA. Systematic review: case-fatality rates of recurrent venous thromboembolism and major bleeding events among patients treated for venous thromboembolism. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(9):578–89. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-152-9-201005040-00008 PubMed PMID: 20439576. Epub 2010/05/05.

Fahrni J, Husmann M, Gretener SB, Keo HH. Assessing the risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism—a practical approach. Vasc Health Risk Manage. 2015;11:451–9. https://doi.org/10.2147/vhrm.s83718 PubMed PMID: 26316770; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4544622. Epub 2015/09/01.

Nieto JA, Solano R, Ruiz-Ribo MD, Ruiz-Gimenez N, Prandoni P, Kearon C, et al. Fatal bleeding in patients receiving anticoagulant therapy for venous thromboembolism: findings from the RIETE registry. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8(6):1216–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.03852.x PubMed PMID: 20345727. Epub 2010/03/30.

Rodger MA, Kahn SR, Wells PS, Anderson DA, Chagnon I, Le Gal G, et al. Identifying unprovoked thromboembolism patients at low risk for recurrence who can discontinue anticoagulant therapy. CMAJ. 2008;179(5):417–26. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.080493 PubMed PMID: 18725614; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2518177. Epub 2008/08/30.

Tosetto A, Iorio A, Marcucci M, Baglin T, Cushman M, Eichinger S, et al. Predicting disease recurrence in patients with previous unprovoked venous thromboembolism: a proposed prediction score (DASH). J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10(6):1019–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1538-7836.2012.04735.x PubMed PMID: 22489957. Epub 2012/04/12.

Eichinger S, Heinze G, Jandeck LM, Kyrle PA. Risk assessment of recurrence in patients with unprovoked deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism: the Vienna prediction model. Circulation. 2010;121(14):1630–6. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.109.925214 PubMed PMID: 20351233. Epub 2010/03/31.

Tritschler T, Mean M, Limacher A, Rodondi N, Aujesky D. Predicting recurrence after unprovoked venous thromboembolism: prospective validation of the updated Vienna prediction model. Blood. 2015;126(16):1949–51. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2015-04-641225 PubMed PMID: 26341256. Epub 2015/09/06.

Sundquist K, Sundquist J, Svensson PJ, Zoller B, Memon AA. Role of family history of venous thromboembolism and thrombophilia as predictors of recurrence: a prospective follow-up study. J Thromb Haemost. 2015;13(12):2180–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/jth.13154 PubMed PMID: 26407905. Epub 2015/09/27.

Schulman S. Update on the treatment of venous thromboembolism. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2016;42(8):891–8. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0036-1592305 PubMed PMID: 27764881. Epub 2016/10/21.

Prandoni P, Barbar S, Milan M, Vedovetto V, Pesavento R. The risk of recurrent thromboembolic disorders in patients with unprovoked venous thromboembolism: new scenarios and opportunities. Eur J Intern Med. 2014;25(1):25–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2013.09.005 PubMed PMID: 24120221. Epub 2013/10/15.

Ambros V. The functions of animal microRNAs. Nature. 2004;431(7006):350–5. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature02871 PubMed PMID: 15372042. Epub 2004/09/17.

Miranda KC, Huynh T, Tay Y, Ang YS, Tam WL, Thomson AM, et al. A pattern-based method for the identification of microRNA binding sites and their corresponding heteroduplexes. Cell. 2006;126(6):1203–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.031 PubMed PMID: 16990141. Epub 2006/09/23.

Weber JA, Baxter DH, Zhang S, Huang DY, Huang KH, Lee MJ, et al. The microRNA spectrum in 12 body fluids. Clin Chem. 2010;56(11):1733–41. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2010.147405 PubMed PMID: 20847327; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4846276. Epub 2010/09/18.

Arroyo JD, Chevillet JR, Kroh EM, Ruf IK, Pritchard CC, Gibson DF, et al. Argonaute2 complexes carry a population of circulating microRNAs independent of vesicles in human plasma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(12):5003–8. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1019055108 PubMed PMID: 21383194; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3064324. Epub 2011/03/09.

Vickers KC, Palmisano BT, Shoucri BM, Shamburek RD, Remaley AT. MicroRNAs are transported in plasma and delivered to recipient cells by high-density lipoproteins. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13(4):423–33. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncb2210 PubMed PMID: 21423178; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPmc3074610. Epub 2011/03/23.

Zampetaki A, Kiechl S, Drozdov I, Willeit P, Mayr U, Prokopi M, et al. Plasma microRNA profiling reveals loss of endothelial miR-126 and other microRNAs in type 2 diabetes. Circ Res. 2010;107(6):810–7. https://doi.org/10.1161/circresaha.110.226357 PubMed PMID: 20651284. Epub 2010/07/24.

Mitchell PS, Parkin RK, Kroh EM, Fritz BR, Wyman SK, Pogosova-Agadjanyan EL, et al. Circulating microRNAs as stable blood-based markers for cancer detection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(30):10513–8. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0804549105 PubMed PMID: 18663219; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPmc2492472. Epub 2008/07/30.

Tijsen AJ, Creemers EE, Moerland PD, de Windt LJ, van der Wal AC, Kok WE, et al. MiR423-5p as a circulating biomarker for heart failure. Circ Res. 2010;106(6):1035–9. https://doi.org/10.1161/circresaha.110.218297 PubMed PMID: 20185794. Epub 2010/02/27.

Wang X, Sundquist K, Hedelius A, Palmer K, Memon AA, Sundquist J. Circulating microRNA-144-5p is associated with depressive disorders. Clin Epigenetics. 2015;7(1):69. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13148-015-0099-8 PubMed PMID: 26199675; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPmc4509564. Epub 2015/07/23.

Wang X, Sundquist K, Elf JL, Strandberg K, Svensson PJ, Hedelius A, et al. Diagnostic potential of plasma microRNA signatures in patients with deep-vein thrombosis. Thromb Haemost. 2016;116(2):328–36. https://doi.org/10.1160/th16-01-0071 PubMed PMID: 27197074. Epub 2016/05/20.

Qin J, Liang H, Shi D, Dai J, Xu Z, Chen D, et al. A panel of microRNAs as a new biomarkers for the detection of deep vein thrombosis. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2015;39(2):215–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11239-014-1131-0 PubMed PMID: 25244974. Epub 2014/09/24.

Xiao J, Jing ZC, Ellinor PT, Liang D, Zhang H, Liu Y, et al. MicroRNA-134 as a potential plasma biomarker for the diagnosis of acute pulmonary embolism. J Transl Med. 2011;9:159. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5876-9-159 PubMed PMID: 21943159; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPmc3189884. Epub 2011/09/29.

Starikova I, Jamaly S, Sorrentino A, Blondal T, Latysheva N, Sovershaev M, et al. Differential expression of plasma miRNAs in patients with unprovoked venous thromboembolism and healthy control individuals. Thromb Res. 2015;136(3):566–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.thromres.2015.07.005 PubMed PMID: 26235746. Epub 2015/08/04.

Jiang Z, Ma J, Wang Q, Wu F, Ping J, Ming L. Combination of circulating miRNA-320a/b and D-dimer improves diagnostic accuracy in deep vein thrombosis patients. Med Sci Monit. 2018;24:2031–7 Epub 2018/04/07. PubMed PMID: 29622762; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5903311.

Isma N, Svensson PJ, Gottsater A, Lindblad B. Prospective analysis of risk factors and distribution of venous thromboembolism in the population-based Malmo thrombophilia study (MATS). Thromb Res. 2009;124(6):663–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.thromres.2009.04.022 PubMed PMID: 19497611. Epub 2009/06/06.

Memon AA, Sundquist K, Wang X, Svensson PJ, Sundquist J, Zoller B. Transforming growth factor (TGF)-beta levels and unprovoked recurrent venous thromboembolism. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2014;38(3):348–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11239-013-1047-0 PubMed PMID: 24402195. Epub 2014/01/10.

Marino MJ. How often should we expect to be wrong? P values, and the expected prevalence of false discoveries. Biochemical pharmacology: Statistical power; 2017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcp.2017.12.011. PubMed PMID: 29248599. Epub 2017/12/19

Eichinger S, Hron G, Kollars M, Kyrle PA. Prediction of recurrent venous thromboembolism by endogenous thrombin potential and D-dimer. Clin Chem. 2008;54(12):2042–8. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2008.112243 PubMed PMID: 18948369. Epub 2008/10/25.

Kyrle PA, Hron G, Eichinger S, Wagner O. Circulating P-selectin and the risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism. Thromb Haemost. 2007;97(6):880–3 Epub 2007/06/06. PubMed PMID: 17549288.

Zabczyk M, Plens K, Wojtowicz W, Undas A. Prothrombotic fibrin clot phenotype is associated with recurrent pulmonary embolism after discontinuation of anticoagulant therapy. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2017;37(2):365–73. https://doi.org/10.1161/atvbaha.116.308253 PubMed PMID: 28062504. Epub 2017/01/08.

Cieslik J, Mrozinska S, Broniatowska E, Undas A. Altered plasma clot properties increase the risk of recurrent deep vein thrombosis: a cohort study. Blood. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2017-07-798306 PubMed PMID: 29242187. Epub 2017/12/16.

Tritschler T, Limacher A, Mean M, Rodondi N, Aujesky D. Usefulness of D-dimer testing in predicting recurrence in elderly patients with unprovoked venous thromboembolism. Am J Med. 2017;130(10):1221–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.04.018 PubMed PMID: 28522384. Epub 2017/05/20.

Shetty S, Kulkarni B, Pai N, Mukundan P, Kasatkar P, Ghosh K. JAK2 mutations across a spectrum of venous thrombosis cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 2010;134(1):82–5. https://doi.org/10.1309/ajcp7vo4haizyatp PubMed PMID: 20551270. Epub 2010/06/17.

Stefanini L, Bergmeier W. RAP1-GTPase signaling and platelet function. J Mol Med (Berlin, Germany). 2016;94(1):13–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00109-015-1346-3 PubMed PMID: 26423530; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4707086. Epub 2015/10/02.

Guidetti GF, Canobbio I, Torti M. PI3K/Akt in platelet integrin signaling and implications in thrombosis. Adv Biol Regul. 2015;59:36–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbior.2015.06.001 PubMed PMID: 26159296. Epub 2015/07/15.

Severin S, Ghevaert C, Mazharian A. The mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathways: role in megakaryocyte differentiation. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8(1):17–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03658.x PubMed PMID: 19874462. Epub 2009/10/31.

Lim CS, Kiriakidis S, Sandison A, Paleolog EM, Davies AH. Hypoxia-inducible factor pathway and diseases of the vascular wall. J Vasc Surg. 2013;58(1):219–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2013.02.240 PubMed PMID: 23643279. Epub 2013/05/07.

Lorthongpanich C, Jiamvoraphong N, Supraditaporn K, Klaihmon P, UP Y, Issaragrisil S. The hippo pathway regulates human megakaryocytic differentiation. Thromb Haemost. 2017;117(1):116–26. https://doi.org/10.1160/th16-07-0564 PubMed PMID: 27786336. Epub 2016/10/28.

Tijsen AJ, van der Made I, van den Hoogenhof MM, Wijnen WJ, van Deel ED, de Groot NE, et al. The microRNA-15 family inhibits the TGFbeta-pathway in the heart. Cardiovasc Res. 2014;104(1):61–71. https://doi.org/10.1093/cvr/cvu184 PubMed PMID: 25103110. Epub 2014/08/12.

Wang J, Song Y, Zhang Y, Xiao H, Sun Q, Hou N, et al. Cardiomyocyte overexpression of miR-27b induces cardiac hypertrophy and dysfunction in mice. Cell research. 2012;22(3):516–27. https://doi.org/10.1038/cr.2011.132 PubMed PMID: 21844895; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3292295. Epub 2011/08/17.

Bayoumi AS, Teoh JP, Aonuma T, Yuan Z, Ruan X, Tang Y, et al. MicroRNA-532 protects the heart in acute myocardial infarction, and represses prss23, a positive regulator of endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Cardiovasc Res. 2017;113(13):1603–14. https://doi.org/10.1093/cvr/cvx132 PubMed PMID: 29016706; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5852516. Epub 2017/10/11.

Nordstrom BL, Evans MA, Murphy BR, Nutescu EA, Schein JR, Bookhart BK. Risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism among deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism patients treated with warfarin. Curr Med Res Opin. 2015;31(3):439–47. https://doi.org/10.1185/03007995.2014.998814 PubMed PMID: 25495136. Epub 2014/12/17.

Cannegieter SC, van Hylckama Vlieg A. Venous thrombosis: understanding the paradoxes of recurrence. J Thromb Haemost. 2013;11(Suppl 1):161–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/jth.12263 PubMed PMID: 23809120. Epub 2013/07/17.

Franchini M, Mannucci PM. Venous and arterial thrombosis: different sides of the same coin? Eur J Intern Med. 2008;19(7):476–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2007.10.019 PubMed PMID: 19013373. Epub 2008/11/18.

Prandoni P. Venous and arterial thrombosis: two aspects of the same disease? Clin Epidemiol. 2009;1:1–6 Epub 2009/01/01. PubMed PMID: 20865079; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2943163.

Lowe GD. Common risk factors for both arterial and venous thrombosis. Br J Haematol. 2008;140(5):488–95. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06973.x PubMed PMID: 18275426. Epub 2008/02/16.

Wang F, Long G, Zhao C, Li H, Chaugai S, Wang Y, et al. Atherosclerosis-related circulating miRNAs as novel and sensitive predictors for acute myocardial infarction. PloS one. 2014;9(9):e105734. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0105734 PubMed PMID: 25184815; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4153586. Epub 2014/09/04.

Ding S, Huang H, Xu Y, Zhu H, Zhong C. MiR-222 in Cardiovascular Diseases: Physiology and Pathology. BioMed Res Int. 2017;2017:4962426. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/4962426 PubMed PMID: 28127557; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5239839. Epub 2017/01/28.

Ovchinnikova ES, Schmitter D, Vegter EL, Ter Maaten JM, Valente MA, Liu LC, et al. Signature of circulating microRNAs in patients with acute heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2016;18(4):414–23. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejhf.332 PubMed PMID: 26345695. Epub 2015/09/09.

Watson CJ, Gupta SK, O'Connell E, Thum S, Glezeva N, Fendrich J, et al. MicroRNA signatures differentiate preserved from reduced ejection fraction heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2015;17(4):405–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejhf.244 PubMed PMID: 25739750; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4418397. Epub 2015/03/06.

Bye A, Rosjo H, Nauman J, Silva GJ, Follestad T, Omland T, et al. Circulating microRNAs predict future fatal myocardial infarction in healthy individuals - the HUNT study. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2016;97:162–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yjmcc.2016.05.009 PubMed PMID: 27192016. Epub 2016/05/19.

Zampetaki A, Willeit P, Tilling L, Drozdov I, Prokopi M, Renard JM, et al. Prospective study on circulating microRNAs and risk of myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(4):290–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2012.03.056 PubMed PMID: 22813605. Epub 2012/07/21.

Vegter EL, Ovchinnikova ES, van Veldhuisen DJ, Jaarsma T, Berezikov E, van der Meer P, et al. Low circulating microRNA levels in heart failure patients are associated with atherosclerotic disease and cardiovascular-related rehospitalizations. Clin Res Cardiol. 2017;106(8):598–609. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00392-017-1096-z PubMed PMID: 28293796; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5529487. Epub 2017/03/16.

Pilbrow AP, Cordeddu L, Cameron VA, Frampton CM, Troughton RW, Doughty RN, et al. Circulating miR-323-3p and miR-652: candidate markers for the presence and progression of acute coronary syndromes. Int J Cardiol. 2014;176(2):375–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.07.068 PubMed PMID: 25124998. Epub 2014/08/16.

Ellis KL, Cameron VA, Troughton RW, Frampton CM, Ellmers LJ, Richards AM. Circulating microRNAs as candidate markers to distinguish heart failure in breathless patients. Eur J Heart Fail. 2013;15(10):1138–47. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurjhf/hft078 PubMed PMID: 23696613. Epub 2013/05/23.

Chen C, Shenglan Y, Feng W, Guangwen L, Xu Y, Fuqiong C, et al. e0613 Plasma microRNA-361-5p as a biomarker of chronic heart failure. Heart. 2010;96(Suppl 3):A189-A. https://doi.org/10.1136/hrt.2010.208967.613.

Wang X, Sundquist J, Zoller B, Memon AA, Palmer K, Sundquist K, et al. Determination of 14 circulating microRNAs in Swedes and Iraqis with and without diabetes mellitus type 2. PloS one. 2014;9(1):e86792. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0086792 PubMed PMID: 24497980; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPmc3907562. Epub 2014/02/06.

Blondal T, Jensby Nielsen S, Baker A, Andreasen D, Mouritzen P, Wrang Teilum M, et al. Assessing sample and miRNA profile quality in serum and plasma or other biofluids. Methods (San Diego, Calif). 2013;59(1):S1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymeth.2012.09.015 PubMed PMID: 23036329. Epub 2012/10/06.

Mestdagh P, Van Vlierberghe P, De Weer A, Muth D, Westermann F, Speleman F, et al. A novel and universal method for microRNA RT-qPCR data normalization. Genome biology. 2009;10(6):R64. https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2009-10-6-r64 PubMed PMID: 19531210; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPmc2718498. Epub 2009/06/18.

Xie F, Xiao P, Chen D, Xu L, Zhang B. miRDeepFinder: a miRNA analysis tool for deep sequencing of plant small RNAs. Plant Mol Biol. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11103-012-9885-2 PubMed PMID: 22290409. Epub 2012/02/01.

Lu TP, Lee CY, Tsai MH, Chiu YC, Hsiao CK, Lai LC, et al. miRSystem: an integrated system for characterizing enriched functions and pathways of microRNA targets. PLoS One. 2012;7(8):e42390. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0042390 PubMed PMID: 22870325; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPmc3411648. Epub 2012/08/08.

Wang X. Improving microRNA target prediction by modeling with unambiguously identified microRNA-target pairs from CLIP-Ligation studies. Bioinformatics. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btw002 PubMed PMID: 26743510. Epub 2016/01/09.

Chou CH, Shrestha S, Yang CD, Chang NW, Lin YL, Liao KW, et al. miRTarBase update 2018: a resource for experimentally validated microRNA-target interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(D1):D296–d302. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkx1067 PubMed PMID: 29126174; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5753222. Epub 2017/11/11.

Kanehisa M, Furumichi M, Tanabe M, Sato Y, Morishima K. KEGG: new perspectives on genomes, pathways, diseases and drugs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(D1):D353–d61. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkw1092 PubMed PMID: 27899662; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5210567. Epub 2016/12/03.

Christiansen SC, Naess IA, Cannegieter SC, Hammerstrom J, Rosendaal FR, Reitsma PH. Inflammatory cytokines as risk factors for a first venous thrombosis: a prospective population-based study. PLoS Med. 2006;3(8):e334. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0030334 PubMed PMID: 16933968; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC1551920. Epub 2006/08/29.

Romer LH, Birukov KG, Garcia JG. Focal adhesions: paradigm for a signaling nexus. Circ Res. 2006;98(5):606–16. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.RES.0000207408.31270.db PubMed PMID: 16543511. Epub 2006/03/18.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank science editor Patrick Reilly for proofreading of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grants awarded to Bengt Zöller by the Swedish Heart-Lung Foundation, ALF funding from Region Skåne awarded to Bengt Zöller, Jan Sundquist, and Kristina Sundquist, and grants awarded to Bengt Zöller, Kristina Sundquist and Jan Sundquist by the Swedish Research Council.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors, XW, KS, PJS, HR, KP, AAM, JS, BZ, contributed to the conception and design of the study. PJS acquired the samples. XW and BZ designed the experiments. XW and HR conducted the molecular studies and performed the experiments. XW and AAM participated in the samples selection. XW, KS, PJS, KP, HR, JS, and BZ contributed to the data analysis and interpretation. XW and KP drafted the manuscript. All authors revised it critically and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was performed according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All the patients have given their informed written consent before enrollment in the MATS study. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Lund University, (LU 237/2007).

Consent for publication

Written informed consents were obtained from all enrolled individuals prior to their participation.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Figure S1. The graph shows the raw Ct values for the control assays on all the samples (n = 78). Figure S2 Differential expression of 14 miRNAs in cases compared to controls significant after adjusting for the false discovery rate using the Benjamini-Hochberg correction. Fold changes (Fold change = 2ΔCt cases − ΔCt controls) with 95% CI. (PDF 282 kb)

Additional file 2:

Table S1. Presentation of the 110 miRNAs (ΔCt = Ctglobal mean − CtmiR of interest) in cases and controls. (XLSX 17 kb)

Additional file 3:

Table S2. Eighty-two KEGG pathway annotation of the miRNA Targets (DAVID 6.8). (XLSX 15 kb)

Additional file 4:

Table S3. Correlation between plasma clot parameters and miRNAs associated with recurrent VTE (n = 75). (DOC 45 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, X., Sundquist, K., Svensson, P.J. et al. Association of recurrent venous thromboembolism and circulating microRNAs. Clin Epigenet 11, 28 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13148-019-0627-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13148-019-0627-z