Abstract

Background

Limited information exists regarding sleep disorders in gout. Our objective was to assess the burden of sleep disorders in people with gout.

Methods

A brief anonymized Internet survey of people with physician-diagnosed gout who visited a gout education website assessed the frequency of sleep problems, sleep quality over the past 24 h (0 = best possible sleep, 10 = worst possible sleep), daytime sleepiness on a typical day (0 = none and 10 = most sleepy during the day), sleep quantity (number of hours of sleep), and the frequency of snoring or gasping, and snorting or stopping breathing during the sleep, using validated questionnaires, including the NHANES 2016 sleep questionnaire. We used Chi-square test to compare the categorical and t test the continuous variables.

Results

Of the 454 website visitors who clicked the survey, 320 survey respondents reported physician-diagnosed gout. Mean age was 57 years (standard deviation [SD], 13.4), 72% were male, 77% were White, and mean gout duration was 7.6 (SD, 11). Of the respondents, 23% reported doctor-diagnosed sleep disorder (sleep apnea, 17%; sleep study ordered, diagnosis pending, 4%; other sleep disorder 2%). A mean 6.7 h of sleep per night was reported (SD, 1.3). Eighty-six percent reported snoring during sleep and 45% reported having snorted, gasped, or stopped breathing while asleep. Two thirds of the patients reported feeling sleepy during the day, at least 3–4 times a month or more. Sleep quality was 5.5 (SD, 2.6), and daytime sleepiness was 3.5 (SD, 2.6) on a 0–10 scale (higher = worse).

Conclusions

People with physician-diagnosed gout reported frequent sleep disorders and daytime sleepiness in an Internet survey. More in-depth studies are needed to better understand the association of gout with sleep disorders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Sleep disorders constitute a major public health burden for the US adults with a prevalence of 6% according to the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2005–2006 [1], obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) being the most common type [2]. Undiagnosed and un- or under-treated OSA was estimated to cost the U.S. $150 billion in 2015 according to a recent report [3], and the health care savings with proper diagnosis could be $100 billion [4]. OSA is associated with significant morbidity [5, 6] and reduced work productivity [7]; cardiovascular morbidity may be related to oxidative stress and inflammation [8]. Effective treatments are available for OSA and other sleep disorders that can reduce morbidity and improve quality of life and work productivity [9,10,11].

Both gout [12] and sleep apnea [13] (a common form of sleep disorder) are associated with metabolic syndrome, defined as the presence of glucose intolerance, hypertension, atherogenic dyslipidemia, and obesity [14]. A recent case-control matched the UK study that used primary care/general practice data reported that gout was associated with 1.4-fold higher risk of any sleep problem, with 50% higher risk of OSA and 37% higher risk of non-sleep apnea problems [15]. An analysis of the 5% random US Medicare data showed that gout was independently associated with a 2-fold higher risk of OSA, after adjusting for demographics, comorbidity, cardiovascular disease, and medications used for the treatment of gout and cardiovascular disease [16]. Another study examined the Health Improvement Network (THIN) database in the UK and found that the incidence of gout was increased by 50% in people with vs. without baseline OSA [17], indicating the OSA may be a risk factor for gout. A study of the US Medicare population, mostly 65 years or older, revealed that gout was associated with a 2-fold higher risk of incident OSA [18]. These study findings indicate that gout and OSA are associated with each other, likely related to both sharing metabolic syndrome comorbidities.

Several biologic mechanisms potentially link OSA to a higher risk of gout and gout flares, including hypoxia associated with OSA leading to enhanced nucleotide turnover subsequently leading to hyperuricemia, and increased urinary urate to creatinine ratio [19,20,21] or possible activation of pathways that accelerate T cell immune response can increase the risk of development of cell-mediated autoimmune disease such as gout [22]. Conversely, gout-associated oxidative stress and acute and chronic inflammation through NALP3 (NACHT, LRR and PYD domains-containing protein 3) inflammasome activation and cytokine activation can put an individual at risk for developing OSA, since these pathways are activated in both these conditions [23,24,25,26,27]. The exact mechanisms for association either way have not been defined and will need careful examination with basic, clinical and translational research. A long latent period for both conditions, gout and OSA, makes the determination of cause-and-effect difficult, if not impossible.

Gout is the most common inflammatory arthritis that affects 4% Americans, is often symptomatic and 63% of gout patients have metabolic syndrome comorbidities [12, 28], risk factors for OSA. A great majority of patients affected with OSA remain undiagnosed [29, 30], a major quality gap [2]. Gout, if shown to be associated with OSA, can serve an early indicator of sleep apnea and help its diagnosis [31, 32]. Recent qualitative studies in patients with gout identified that sleep disorders are experienced commonly and likely contribute to quality of life (QOL) deficits in these patients [33, 34]. If sleep disorders were found to be common in people with gout, a quality improvement (QI) initiative in the gout clinic would be to screen gout patients for sleep disorders and thus improve the clinic intake process for effective screening of an important comorbidity. Early diagnosis and appropriate management of sleep disorders (including OSA) in people with gout can fill two quality gaps (diagnosis, management) and may improve outcomes in people with gout and gout/OSA overlap [9, 10]. Due to limited information available for sleep disorders in gout, this quality improvement (QI) initiative was conducted to examine the frequency of sleep problems and disorders in people with gout, using an anonymized Internet survey.

Methods

People visiting the Gout and Uric Acid Education Society’s (GUAES) website (http://gouteducation.org) were invited to participate in a brief anonymized Internet survey from January to October 2017. People who reported physician-diagnosed gout were invited to respond to a survey that queried people about demographics (age, gender, race/ethnicity using the NIH Collaboratory definition [35]), the duration of gout diagnosis, gout flares, the number of medical comorbidities (including gout), and overall symptoms from gout and receipt of and adherence (the number of days medication was missed) to prescribed urate-lowering therapy (ULT; allopurinol or febuxostat). Questions regarding gout duration and gout flares were the same as used previously by us [36]. The number of gout flares’ question was similar to that used previously for patient-reported flare as part of validated gout flare definition [37], in addition providing some details of a gout flare (“How many gout flares did you have in the last year? A typical gout flare is associated with severe pain, swelling and inability/difficulty to move the joint, and lasts 7–10 days without treatment”).

The frequency of sleep problems including sleep apnea was assessed. Sleep quality was assessed using a single-item validated patient-reported Sleep Quality Scale [38] that assessed the quality of sleep over the past 24 h on a 0 (best possible sleep) to 10 (worst possible sleep) scale. Daytime sleepiness was assessed with a single-item validated question, asking patient about daytime sleepiness on a typical day with 0 meaning none and 10 being the highest, i.e., the most sleepy during the day [39]. Other sleep quality and quantity outcomes were assessed using the NHANES 2016 sleep questionnaire that included the number of hours of sleep, and the frequency of snoring; gasping, snorting, or stopping breathing during the sleep; and feeling excessively/overly sleep during the day [40].

As a QA/QI initiative, this anonymized Internet survey did not require an approval from the Institutional Review Board. No written informed consent was needed since the anonymized survey was offered for voluntary participation at the GUAES patient education website informing people that they could click out of the survey if not interested, this will not directly benefit them and they can stop participating at any time. Chi-square test were used for categorical and t-test for continuous variables. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Of the 454 website visitors who clicked the survey, 320 survey respondents reported physician-diagnosed gout. The mean respondent age was 57 years (SD, 13.4), 72% (166/232) were male, and 77% (179/232) were White (Table 1). Gout duration, gout flares in the last month, and the number of medical comorbidities (including gout) were 7.6 years (SD, 11), 1.5 flares (SD, 1.3), and 2.7 (2.6), respectively (Table 1). Only 16% (45/286) reported no gout flare in the last year, and only 10% (24/241) reported mild or no symptoms of gout.

Of the respondents, 23% (56/241) reported doctor-diagnosed sleep disorder, which was sleep apnea (17%) or possible sleep apnea (4%, sleep study ordered, diagnosis pending) in the majority and other sleep problems in 2% (Table 2). Sleep quality on a 0–10 single-item scale (10 = best possible sleep) over the past 24 h was 5.5 (SD, 2.6). Daytime sleepiness on a 0–10 single-item scale (10 = most daytime sleepiness) was 3.5 (SD, 2.6).

People with gout reported a mean 6.7 h of sleep per night (SD, 1.3). Only 14% (26/179) respondents never snored during the night, i.e., 86% (153/179) reported snoring during sleep with 34% (60/179) reported snoring 5 or more nights in the last week; 45% (71/157) reported having snorted, gasped, or stopped breathing while asleep (Table 2). Two-thirds of the patients reported feeling sleepy during the day, at least 3–4 times a month or more.

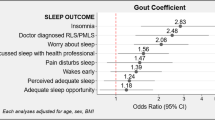

No age, sex, or race differences were seen in patient-reported sleep parameters, except the following: (1) compared to males with gout, females with gout reported better sleep quality in the last 7 days, 6 vs. 4.9 (p = 0.002), but more daytime sleepiness, 3.1 vs. 4.6 (p = 0.001); (2) compared to people ≥ 65 years with gout, younger people with gout reported more daytime sleepiness (p = 0.03) and more frequent snorting, gasping, or stopping breathing while asleep in the past 12 months (p = 0.01) (Appendix).

Discussion

In an anonymized cross-sectional Internet gout survey of people visiting a gout education website, a quarter of respondents with gout reported sleep problems, with sleep apnea being the most commonly diagnosed sleep disorder. Nine out of 10 respondents reported snoring during sleep, and 5 out of 10 reported snorting, gasping, or stopping breathing while asleep. This high prevalence of snoring, snorting, gasping, or stopping breathing while asleep indicates that the actual prevalence of OSA may be even higher than the 17% physician-confirmed OSA diagnosis reported by people with gout. Even the 17% prevalence of sleep apnea in gout is much higher than the 4–7% reported in the US general population previously [2]. Our recent US Medicare study reported a 3-fold higher unadjusted and 2-fold higher adjusted hazard ratio of a new diagnosis of OSA in Medicare-recipient adults with gout, who were mostly 65 years or older [18]. The current study supports the finding of significantly higher prevalence of sleep apnea in people with gout, in an independent sample of subjects from across the world, with no geographic or age limits.

Sleep quality in gout on the single-item was much lower than that reported from two trials of pregabalin in fibromyalgia, a condition where sleep abnormalities are very common and often presenting features of the disorder, 5.5 vs. 6.2–6.7 [38]. Daytime sleepiness in this gout cohort was much lower compared to a cohort of people with diagnosed/known sleep disorders, 3.5 vs. 6.5 [39], which is not unexpected, since people with known sleep disorders would be expected to be much worse than those with a musculoskeletal disorder (gout). Frequent daytime sleepiness was reported by two thirds of people with gout, which is quite concerning. An interesting finding was that women and younger people with gout were more likely to report daytime sleepiness than their counterparts. These findings have potential clinical implications. Although these findings are not generalizable to gout cohorts reported from gout clinics, the question is whether screening gout patients for sleep disorders in the clinic can aid early diagnosis and treatment of sleep apnea and other sleep disorders and improve patient outcomes. These are important clinical questions that need further study.

So, what are the implications of these study findings for clinical practice? Knowing that both gout and OSA are common in the general population, an earlier recognition of undiagnosed OSA and sleep disorders in people with gout can improve the ability to diagnose and treat sleep disorders. Our study indicates that a clinic QI initiative of querying patients with gout about sleep disorders may be appropriate, low-cost, and practical way to improve the recognition of coexisting sleep disorders in patients with gout. Even in the absence of a subsequent sleep disorder diagnosis, recognizing the impact of gout and gout flares on sleep can lead to a patient-centered care approach. Appropriate referral of patients with severe symptoms and supporting examination findings to a sleep study for confirming/ruling out OSA and/or a sleep expert for diagnosis of OSA and other sleep disorders can fill two quality gaps of delayed/missed diagnosis and delayed treatment of OSA and other sleep disorders.

This study should be interpreted considering study limitations. Findings may only be generalizable to patients with gout who use the Internet, and not all gout patients. The Internet study design may have selected for a younger people, who might be more technologically oriented. However, the use of Internet is growing in all segments of the society, and 70% and 27% of our survey respondents were ≥ 50 and ≥ 65 years old, respectively. Response bias is an important study limitation, and missingness of responses was higher for certain variables/questions such as ULT use (missing, n = 179) and some sleep questions such as snorting/gasping/stopping breathing (n = 163) compared to that noted for race/ethnicity/sex (missing, n = 88). Self-reported sleep parameters are not without limitations, since over-reporting of sleep duration by self-report has been described, and self-report had only moderate correlation with objective assessment of sleep duration [41]. The lack of collection of body weight and body mass index data is another study limitation. A strength of this study was the use of validated sleep measures, including the NHANES 2016 sleep questionnaire, and limiting these analyses to only those with self-reported physician-confirmed gout.

Conclusions

In conclusion, Internet users with self-reported physician-diagnosed gout commonly reported physician-diagnosed sleep disorders. A large proportion of patients with gout also reported frequent snoring, snorting, gasping, or stopping breathing while asleep, indicating an additional cohort with subclinical or undiagnosed OSA. Given high prevalence of sleep disorders in people with gout, further studies are needed to examine the true rates and types of sleep disorders in gout. An early diagnosis and treatment of sleep disorders in gout may reduce its impact and morbidity and may improve quality of life.

Abbreviations

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- OSA:

-

Obstructive sleep apnea

- NHANES:

-

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- QOL:

-

Quality of life

- QI:

-

Quality improvement

- GUAES:

-

Gout and Uric Acid Education Society

- ULT:

-

Urate-lowering therapy

References

Ram S, Seirawan H, Kumar SK, Clark GT. Prevalence and impact of sleep disorders and sleep habits in the United States. Sleep Breath. 2010;14(1):63–70.

Punjabi NM. The epidemiology of adult obstructive sleep apnea. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5(2):136–43.

Frost & Sullivan. Hidden health crisis costing America billions. Underdiagnosing and undertreating obstructive sleep apnea draining healthcare system. Available from: http://www.aasmnet.org/sleep-apnea-economic-impact.aspx. Darien: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2016.

Watson NF. Health care savings: the economic value of diagnostic and therapeutic care for obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med. 2016;12(8):1075–7.

Kaw R. Obstructive sleep apnea in US veterans was associated with increased mortality and morbidity. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(6):JC12.

Basner RC. Cardiovascular morbidity and obstructive sleep apnea. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(24):2339–41.

Nena E, Steiropoulos P, Constantinidis TC, Perantoni E, Tsara V. Work productivity in obstructive sleep apnea patients. J Occup Environ Med. 2010;52(6):622–5.

Gozal D, Kheirandish-Gozal L. Cardiovascular morbidity in obstructive sleep apnea: oxidative stress, inflammation, and much more. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177(4):369–75.

Epstein LJ, Kristo D, Strollo PJ Jr, Friedman N, Malhotra A, Patil SP, Ramar K, Rogers R, Schwab RJ, Weaver EM, et al. Clinical guideline for the evaluation, management and long-term care of obstructive sleep apnea in adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5(3):263–76.

Marin JM, Carrizo SJ, Vicente E, Agusti AG. Long-term cardiovascular outcomes in men with obstructive sleep apnoea-hypopnoea with or without treatment with continuous positive airway pressure: an observational study. Lancet. 2005;365(9464):1046–53.

Jurado-Gamez B, Guglielmi O, Gude-Sampedro F, Buela-Casal G. Effect of CPAP therapy on job productivity and psychosocial occupational health in patients with moderate to severe sleep apnea. Sleep Breath. 2015;19(4):1293–9.

Choi HK, Ford ES, Li C, Curhan G. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in patients with gout: the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57(1):109–15.

Parish JM, Adam T, Facchiano L. Relationship of metabolic syndrome and obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med. 2007;3(5):467–72.

Grundy SM, Brewer HB Jr, Cleeman JI, Smith SC Jr, Lenfant C, American Heart A, National Heart L, Blood I. Definition of metabolic syndrome: report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/American Heart Association conference on scientific issues related to definition. Circulation. 2004;109(3):433–8.

Roddy E, Muller S, Hayward R, Mallen CD. The association of gout with sleep disorders: a cross-sectional study in primary care. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2013;14:119.

Singh JA, Cleveland JD. Gout and the risk of incident obstructive sleep apnea in adults 65 years or older: an observational study. J Clin Sleep Med. 2018;14(9):1521–7.

Zhang Y, Peloquin CE, Dubreuil M, Roddy E, Lu N, Neogi T, Choi HK. Sleep apnea and the risk of incident gout: a population-based, body mass index-matched cohort study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(12):3298–302.

Singh JA, Cleveland JD. Gout and the risk of incident obstructive sleep apnea in adults 65 years or older: an observational study (in press). J Clin Sleep Med. 2018.

Glantzounis GK, Tsimoyiannis EC, Kappas AM, Galaris DA. Uric acid and oxidative stress. Curr Pharm Des. 2005;11(32):4145–51.

Hasday JD, Grum CM. Nocturnal increase of urinary uric acid:creatinine ratio. A biochemical correlate of sleep-associated hypoxemia. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1987;135(3):534–8.

Sahebjani H. Changes in urinary uric acid excretion in obstructive sleep apnea before and after therapy with nasal continuous positive airway pressure. Chest. 1998;113(6):1604–8.

Abrams B. Long-term sleep apnea as a pathogenic factor for cell-mediated autoimmune disease. Med Hypotheses. 2005;65(6):1024–7.

Martinon F, Petrilli V, Mayor A, Tardivel A, Tschopp J. Gout-associated uric acid crystals activate the NALP3 inflammasome. Nature. 2006;440(7081):237–41.

Dalbeth N, Haskard DO. Mechanisms of inflammation in gout. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2005;44(9):1090–6.

Ryan S, Taylor CT, McNicholas WT. Selective activation of inflammatory pathways by intermittent hypoxia in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Circulation. 2005;112(17):2660–7.

Yokoe T, Minoguchi K, Matsuo H, Oda N, Minoguchi H, Yoshino G, Hirano T, Adachi M. Elevated levels of C-reactive protein and interleukin-6 in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome are decreased by nasal continuous positive airway pressure. Circulation. 2003;107(8):1129–34.

Jelic S, Padeletti M, Kawut SM, Higgins C, Canfield SM, Onat D, Colombo PC, Basner RC, Factor P, LeJemtel TH. Inflammation, oxidative stress, and repair capacity of the vascular endothelium in obstructive sleep apnea. Circulation. 2008;117(17):2270–8.

Krishnan E. Inflammation, oxidative stress and lipids: the risk triad for atherosclerosis in gout. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2010;49(7):1229–38.

Kapur V, Strohl KP, Redline S, Iber C, O'Connor G, Nieto J. Underdiagnosis of sleep apnea syndrome in U.S communities. Sleep Breath. 2002;6(2):49–54.

Young T, Evans L, Finn L, Palta M. Estimation of the clinically diagnosed proportion of sleep apnea syndrome in middle-aged men and women. Sleep. 1997;20(9):705–6.

Abrams B. Gout is an indicator of sleep apnea. Sleep. 2005;28(2):275.

Abrams B. Gout as an early warning of concomitant sleep apnea. J Clin Rheumatol. 2010;16(6):305.

Singh JA. Any sleep is a dream far away: a nominal group study assessing how gout affects sleep. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2018;57(11):1925–32.

Singh JA. The impact of gout on patient’s lives: a study of African-American and Caucasian men and women with gout. Arthritis Res Ther. 2014;16(3):R132.

Race/ethnicity data standard - from the NIH Collaboratory Phenotypes, Data Standards, and Data Quality Core. https://www.nihcollaboratory.org/Products/RaceEthnicity_standard.pdf. Accessed 19 Jan 2019.

Singh JA, Edwards NL: Patient perceptions of gout management goals: a cross-sectional Internet survey (In press). JCR 2019.

Gaffo AL, Dalbeth N, Saag KG, Singh JA, Rahn EJ, Mudano AS, Chen YH, Lin CT, Bourke S, Louthrenoo W, et al. Brief report: validation of a definition of flare in patients with established gout. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70(3):462–7.

Cappelleri JC, Bushmakin AG, McDermott AM, Sadosky AB, Petrie CD, Martin S. Psychometric properties of a single-item scale to assess sleep quality among individuals with fibromyalgia. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2009;7:54.

Zallek SN, Redenius R, Fisk H, Murphy C, O'Neill E. A single question as a sleepiness screening tool. J Clin Sleep Med. 2008;4(2):143–8.

NHANES 2016. Sleep disorders questionnaire - SLQ. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/2015-2016/questionnaires/SLQ_I.pdf. Accessed 19 Jan 2019.

Lauderdale DS, Knutson KL, Yan LL, Liu K, Rathouz PJ. Self-reported and measured sleep duration: how similar are they? Epidemiology. 2008;19(6):838–45.

Acknowledgements

I thank Dr. Edwards, the Chairman and the CEO of the Gout and Uric acid Education Society for allowing the posting of this anonymized survey on their website and collecting responses from site visitors.

Funding

This material is the result of work supported by research funds from the Division of Rheumatology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham and the resources and use of facilities at the Birmingham VA Medical Center, Alabama, USA to the study PI (JAS).

Availability of data and materials

We are ready to share the data with colleagues, after obtaining appropriate permissions from the Gout and Uric acid Education Society (GUAES), related to their privacy and data sharing policies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JAS designed the study, developed study protocol, reviewed analyses, and wrote the first draft of the paper and made the decision to submit the final manuscript. The author read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This survey was a Quality Assurance/Quality Improvement (QA/QI) initiative that was conducted as an anonymized survey with no collection of any Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) identifier elements, and therefore it did not require an approval from the Institutional Review Board.

Consent for publication

No individual person’s data were presented in any form in this study and therefore no consent to publish is required.

Competing interests

There are no financial conflicts related directly to this study. JAS has received consultant fees from Crealta/Horizon, Fidia, UBM LLC, Medscape, WebMD, the National Institutes of Health and the American College of Rheumatology. He owns stock options in Amarin Pharmaceuticals, Inc. He is a member of the Veterans Affairs Rheumatology Field Advisory Committee. He is the editor and the Director of the UAB Cochrane Musculoskeletal Group Satellite Center on Network Meta-analysis. He served as a member of the American College of Rheumatology’s (ACR) Annual Meeting Planning Committee (AMPC) and Quality of Care Committees, the Chair of the ACR Meet-the-Professor, Workshop and Study Group Subcommittee, and the co-chair of the ACR Criteria and Response Criteria subcommittee. He is a member of the executive of OMERACT, an organization that develops outcome measures in rheumatology and receives arms-length funding from 36 companies.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Singh, J.A. Self-reported sleep quality and sleep disorders in people with physician-diagnosed gout: an Internet cross-sectional survey. Arthritis Res Ther 21, 36 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-019-1821-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-019-1821-2