Abstract

Background

Cysticercosis caused by cysticercus tenuicollis is a metacestode infection that affects several species of ungulates. It is caused by the larval stage of Taenia hydatigena, an intestinal tapeworm in dogs and wild canids. In the intermediate host, the mature cysticerci are usually found in the omentum, mesentery, and peritoneum, and less frequently in the pleura and pericardium. The migrating larvae can be found mostly in the liver parenchyma causing traumatic hepatitis in young animals. Most infections are chronic and asymptomatic, and are diagnosed at the abattoir. The acute form of infection is unusual in sheep and reports of death in lambs are rare.

Methods

In March 2018, fifteen female lambs presented anorexia, weakness, lethargy, and death secondary to acute visceral cysticercosis. Twelve of them underwent hepatic ultrasonography. Examinations were performed on standing or left lateral recumbent animals.

Results

Livers of affected animals presented rounded margins and a thickened, irregular and hyperechoic surface. Hepatic parenchyma appeared to be wholly or partially affected by lesions characterized by heterogeneous areas crossed by numerous, irregular, anechoic tracts ranging from 1 to 2 cm in length and 0.1 to 0.2 cm in width. Superficial and intraparenchymal cystic structures were also visualized. The presence of lesions was confirmed by anatomopathological examination, and T. hydatigena cysticerci was identified by morphological and molecular characterization of isolates.

Conclusions

Our results highlighted that hepatic ultrasonography is effective for an intra-vitam diagnosis of acute cysticercosis in lambs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The metacestode cysticercus tenuicollis is the larval stage of Taenia hydatigena, a cosmopolitan tapeworm in dogs and wild canids [1,2,3]. The development of T. hydatigena requires two distinct hosts to complete its life-cycle. The adult parasites reside in the intestine of the definitive hosts such as dogs and other carnivores such as foxes, wolves, jackals, lynx, raccoons, bears and cats [4]. The intermediate hosts, generally small ruminants and, less frequently pigs, cattle, deer and other wild species, get infected by ingesting eggs from contaminated pasture [5,6,7]. After the eggs hatch in the small intestine of the intermediate hosts, developing cysticerci migrate to reach the liver, and occasionally other organs such as the lungs and kidneys [8].

Migrating larvae can be found in the liver parenchyma of lambs and piglets within 7–10 days post-infection [9, 10]. Mature cysticerci are usually found in the omentum, mesentery, peritoneum and, less frequently, in the pleura and pericardium [8,9,10,11,12,13]. Clinical signs in intermediate hosts vary according to the severity of infection. Most infections are chronic and asymptomatic, and are not usually identified until slaughter [14].

In severe infections, the migration of a large number of larvae causes severe traumatic hepatitis, peritonitis and even pneumonia, leading to clinical signs and even death [8, 12, 15]. A mortality rate of 19.0% has been described in lambs due to massive hepatic and pulmonary infections [12].

Cysticercosis caused by cysticercus tenuicollis is widespread in sheep in Italy, where an overall prevalence of 14.6% has been reported in lambs. In Sardinia, the economic loss related to cysticercus tenuicollis infection has been estimated at €330,000 per year [16]. Although several attempts have been made for the ante-mortem diagnosis of T. hydatigena cysticercosis by serological tests [17,18,19,20], a final diagnosis of the disease is currently only possible by analyzing the cysts after the animal has been slaughtered.

Although ultrasonography is effective in diagnosing parasitic infections in animals, including other metacestodoses such as cystic echinococcosis and coenurosis [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30], to the best of our knowledge, there are no reports describing the ultrasonographic findings of cysticercus tenuicollis infection in small ruminants.

In this paper we describe the clinical manifestation, ultrasonographic findings, anatomopathological results and molecular characterization of lambs affected by acute visceral cysticercosis by T. hydatigena.

Methods

In March 2018, fifteen female Sarda lambs (native to Sardinia, Italy), from a flock of 100 individuals, four months old, weighing from 15 to 20 kg, presented various degrees of anorexia, lethargy, weakness and death.

The animals had not previously received parasitological treatments. Necropsy on three dead animals revealed acute visceral cysticercosis as the cause of death. The twelve surviving animals underwent physical and coprological examination as well as hepatic ultrasonography.

Coprological examination was carried out using the FLOTAC® technique: specific gravity (s.g.) 1350, and eggs per gram (EPG) or oocysts per gram (OPG) were obtained using a zinc sulphate solution [31, 32]. The ultrasonographic examinations were performed by an experienced operator (AC) with a portable ultrasound unit (My Lab Alpha, Esaote, Florence, Italy) equipped with two multifrequency linear (SL1543; 3-13 MHz) and microconvex (SC3123; 4-9 MHz) probes. Images and video obtained with both probes were acquired and stored for offline review.

Examinations were performed on standing or left lateral recumbent unsedated lambs. The liver was visualized by placing the probe in the cranial right hypochondrium, caudally to the last rib or between the right intercostal spaces [21]. The hepatic parenchyma was examined by transverse and longitudinal sections. Based on ultrasonographic findings, the severity of infection was ranked into 3 classes: severe, when the lesions affected the whole hepatic parenchyma; moderate, when the lesions occupied most of the parenchyma; and mild, when the extent of the injuries was less than the normal parenchyma. The appearance of the liver surface (regularity and thickness) and edges (sharp or rounded) were also examined. During the ultrasonographic examination, B-lines on the diaphragmatic surface of the right lung were also observed along with free abdominal fluid. The animals that died within 24 hours of the ultrasound scan underwent necropsy. Liver and lung parenchyma samples were fixed with 10% neutral buffered formalin solution and embedded in paraffin wax. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin for histopathological examination.

Morphological identification of the parasites was performed according to the previously reported keys [33]. Molecular identification was then performed in order to confirm morphological diagnosis according to Scala et al. [16].

Results

On physical examination, the lambs presented pale mucous membranes (n = 7), body condition score < 3 (n = 5), depression and unwillingness to move (n = 5), inspiratory crackles on pulmonary auscultation (n = 4), hypothermia (n=3), sub-icteric mucous membranes (n = 3), respiratory distress (n = 3), hyperthermia (n = 2), sternal recumbency (n = 2), and abdominal distension (n = 2).

At coprological examination, eggs of gastro-intestinal strongyles (GIS) were detected (average 60 EPG) in eight of the twelve lambs, an average of 30 EPG of Nematodirus spp. were found in four lambs, and all the lambs showed Eimeria spp. oocysts (average 180 OPG).

All the examined lambs showed ultrasonographic evidence of liver lesions. On the basis of the ultrasonographic classification, the infection was scored as severe in six lambs, moderate in five, and mild in only one animal. The severity of clinical symptoms was directly related to the extent and severity of liver injuries.

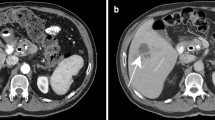

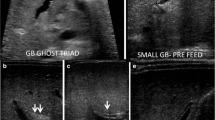

Hepatic lesions were characterized by heterogeneous echotexture and mixed echogenicity (Fig. 1). The injured areas were crossed by several irregular hypo- or anechoic tracts ranging from 1 to 2 cm in length and 0.1 to 0.3 cm in width (Fig. 2). Five severely infected animals presented cystic structures (from 0.5 to 0.7 cm in diameter) localized along the hepatic surface and characterized by a thick and hyperechoic wall, containing a hyperechoic mural branching component surrounded by anechoic fluid (Fig. 3). They also presented intraparenchymal cysts (from 0.3 to 0.4 cm in diameter) containing a point-like hyperechoic structure surrounded by anechoic fluid (Fig. 1b). A Doppler color examination confirmed the cystic nature of these structures (Fig. 4).

Ultrasonographic appearance of the lamb’s liver affected by acute cysticercosis. a Ultrasonographic transversal section of the liver showing a diffusely heterogeneous parenchyma crossed by hypoechoic irregular tracts. The diaphragmatic surface of the liver appears irregular, thickened and hyperechoic (arrow). The lung surface presents several B-lines (asterisks). b Ultrasonographic longitudinal section of the liver showing a diffusely heterogeneous parenchyma in which intraparenchymal cysts are visible (arrowhead). The diaphragmatic surface of the liver appears irregular, thickened and hyperechoic (arrow). The lung surface presents several B-lines (asterisks)

All the lambs with severe infection and three with moderate infection presented rounded liver margins. All the lambs with severe infection and two with moderate infection also presented an irregular, thickened and hyperechoic liver surface. Four lambs with severe and three with moderate liver damage showed enlarged portal lymph nodes. Three animals with severe and one with mild infection presented B-lines on the diaphragmatic surface of the right lung (Fig. 1). Two severely infected lambs also presented evidence of free peritoneal fluid accumulation, which was hypoechoic with suspended echogenic particles. No lamb showed ultrasonographic evidence of biliary system alterations.

Four of the severely infected animals died (n = 2) or were euthanized (n = 2) for welfare reasons, within 24 hours of the ultrasound and underwent necropsy. The surviving lambs (n = 8) underwent medical treatment with oral praziquantel [12]. Two of them, both classified as severely infected, died several days later; however, they were not taken into consideration for this study because too much time had passed since the ultrasound. The other six lambs, five classified as moderately and one as mildly infected, survived the infection and were still alive after one year.

The four lambs that underwent necropsy showed similar gross and histopathological changes. Gross pathology revealed hepatomegaly and perihepatitis with whitish-yellow fibrin depositions on the liver surface (Fig. 5a). All the animals presented free fluid (inflammatory exudate) in the abdomen in which parasitic cysts (3–5 mm) were floating (Fig. 5b). The hepatic surface as well as the parenchyma sections were crossed by multiple, 2–3 mm wide, hemorrhagic wavy tracts (Fig. 5c, d). Several parasitic cysts were detected on the surface and inside the parenchyma of the liver and lungs as well as in the mesentery.

Gross pathology images. a Severe perihepatitis with whitish-yellow fibrin depositions on the diaphragmatic liver surface. b Free abdominal fluid containing several parasitic cysts. c Hepatic surface crossed by multiple hemorrhagic wavy tracts. d Hepatic section showing multiple intraparenchymal hemorrhagic tracts and parasitic cysts

Upon histological examination, the larval tracks appeared to be filled with erythrocytes, neutrophils, eosinophils necrotic cells debris and fibrin. Migrating cysticerci were surrounded by erythrocytes, neutrophils, eosinophils, necrotic cells, lymphocytes and macrophages. Similar lesions were observed in the pulmonary parenchyma.

The morphological characteristics of isolated cysts were consistent with those reported in the literature for T. hydatigena cysticerci, in different stages of maturation [33]. The morphological identification was confirmed by molecular biology and nucleotide sequences showed a 99% identity with T. hydatigena (GenBank: AB792722 and JN831270).

Discussion

The present report demonstrates that ultrasonography is a useful diagnostic tool to identify and define the extent and severity of hepatic lesions caused by cysticercus tenuicollis migration in lambs.

Ultrasonography can be used to directly visualize the parasites and/or to show the lesions caused by them. In this report we have described the ultrasonographic appearance of the hepatic injuries caused by the larval stage migration, as well as the parasite itself. Hepatic lesions were heterogeneous, with mixed echogenicity areas crossed by several hypo- or anechoic irregular tracts. Areas with a non-homogeneous echotexture within the liver parenchyma cannot be considered a specific finding of cysticercus tenuicollis infection, as similar alterations have also been described in ovine fascioliasis [34]. However, our results show that this type of hepatic parenchymal injury, which is not associated with alterations in the biliary system, is highly indicative of cysticercus tenuicollis infection, especially in endemic regions.

Our results showed that the migratory tracts had variable echogenicity: some were completely anechoic, others were hypoechoic with varying shades of gray. The variability was probably due to the different stage of histological development of the hemorrhagic tracts caused by cysticercus tenuicollis migration [11, 13]. The ultrasonographic appearance of intraparenchymal hemorrhagic lesions changes over time: initially they are echogenic and later become hypo- and anechoic [35, 36]. The intra- and extrahepatic alterations visualized by ultrasonography were subsequently confirmed by necropsy: (i) the irregular thickened and hyperechoic liver surface was due to the presence of several superficial tracts and to the perihepatitis; (ii) the rounded liver margin was associated with hepatomegaly [35, 37]; and (iii) the presence of several B-lines on the diaphragmatic surface of the right lung was due to pneumonia secondary to larval migration. In fact, the B-line artifact is a sign of pulmonary interstitial disease and is considered an early sign of pneumonia in ruminants [38, 39].

Hepatic and perihepatic cysts compatible with cysticercus tenuicollis were identified in five lambs. They appeared as cystic structures attached to the visceral surface or inside the hepatic parenchyma. Not all the livers of the lambs displayed parasites, probably because in some animals the larvae were not sufficiently mature to be visualized or because gas in the gastrointestinal tract adjacent to the liver made it impossible to visualize the parasites.

Ultrasonographic evidence of intraparenchymal cysts in sheep has also been described in cystic echinococcosis [21, 24, 25]. However, cystic echinococcosis is characterized by the presence of cystic structures ranging from 0.9 to 10.4 cm in diameter, surrounded by normal or moderately heterogeneous parenchyma in which there is no evidence of migratory tracts [21, 24]. In contrast, the intraparenchymal cysts described in this report were always small (maximum 0.4 cm) and surrounded by severely injured tissue.

In our study, due to the animals’ young age, it would have been unlikely to misdiagnose the two parasites. However, differentiating between cystic echinococcosis and cysticercosis in animals older than 18 months can be difficult or impossible when cysts are attached to the liver surface because their appearance under ultrasound may be identical.

Early diagnosis of cysticercosis caused by T. hydatigena in live animals is important from an epidemiological point of view because positive animals indicate the level of environmental contamination with other metacestodoses. Although there are differences due to the species, T. hydatigena share the same hosts and life-cycle modality with Taeniid species of zoonotic interest such as E. granulosus (sensu lato) and T. multiceps both in domestic and wildlife environments [40,41,42,43].

Interestingly, cysticercosis is usually present in the first months of age of the intermediate hosts (as in our case), while diagnosis of coenurosis is usually possible in animals between 4 and 18 months [44], and a diagnosis of cystic echinococcosis is usually obtained in animals older than 18 months, in relation to the growth rates of the cysts, which influence the reliability of the diagnosis. In E. granulosus (sensu lato), the growth rate is slow and variable and dependent on the species or strains of the parasite [45] and the species of the host and the degree of infection. In sheep, cysts increase by between 1 and 5 cm in diameter per year [46], and from 1–2 mm to 10 mm per year in humans [47]. There is an intraspecific variability in the genetic structure of T. hydatigena, which is consistent with biochemical and morphological studies that suggest the existence of other variants of these parasites [48]. It would thus be interesting to understand whether or not there are also different rates of growth of T. hydatigena cysticerci.

We believe that cysticercosis by T. hydatigena, is not only an economic problem for farmers and the meat industry, but could also be life threatening for young animals, as already reported [16].

Ultrasonography is increasingly used as an intra-vitam test to diagnose parasitic diseases in small ruminants, probably because of the widespread use of portable ultrasound equipment by sheep practitioners [29, 49]. Hepatic ultrasonography could be a useful intra-vitam test to diagnose cysticercus tenuicollis infections in sheep. However, the application of this method could be limited by the need to use high-quality portable ultrasound equipment by experienced staff, which could increase the costs of the examinations. Moreover, it is not clear how sensitive and specific the ultrasonography would need to be in order to reveal mild infections in asymptomatic animals, which represent the majority of cases. Further studies are thus needed to determine whether the method can be used as part of epidemiological surveillance and control programmes.

Conclusions

The present report demonstrates that ultrasonography can identify and define the extension and the severity of hepatic lesions caused by cysticercus tenuicollis in lambs. This technique could be used as an intra vitam diagnostic test for cysticercus tenuicollis parasitosis in small ruminants.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- EPG:

-

Eggs per gram

- OPG:

-

Oocysts per gram

- AC:

-

Andrea Corda

- GIS:

-

Gastro-intestinal strongyles

References

Featherston DW. Taenia hydatigena: I. Growth and development of adult stage in the dog. Exp Parasitol. 1969;25:329–38.

Dalimi A, Sattari A, Motamedi G. A study on intestinal helminthes of dogs, foxes and jackals in the western part of Iran. Vet Parasitol. 2006;142:129–33.

Saeed I, Maddox-Hyttel C, Monrad J, Kapel CMO. Helminths of red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) in Denmark. Vet Parasitol. 2006;139:168–79.

Conboy G. Cestodes of dogs and cats in North America. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2009;39:1075–90.

Sgroi G, Varcasia A, Dessì G, D’Alessio N, Pacifico L, Buono F, et al. Massive Taenia hydatigena cysticercosis in a wild boar (Sus scrofa) from Italy. Acta Parasitol. 2019;64:938–41.

Nguyen MTT, Gabriël S, Abatih EN, Dorny P. A systematic review on the global occurrence of Taenia hydatigena in pigs and cattle. Vet Parasitol. 2016;226:97–103.

Cengiz G, Yucel Tenekeci G, Bilgen N. Molecular and morphological characterization of Cysticercus tenuicollis in red deer (Cervus elaphus) from Turkey. Acta Parasitol. 2019;64:652–7.

Edwards GT, Herbert IV. The course of Taenia hydatigena infections in growing pigs and lambs: clinical signs and post-mortem examination. Br Vet J. 1980;136:256–64.

Sweatman GK, Plummer PJG. The biology and pathology of the tapeworm Taenia Hydatigena in domestic and wild hosts. Can J Zool. 1957;35:93–109.

Blazek K, Schramlová J, Hulínská D. Pathology of the migration phase of Taenia hydatigena (Pallas, 1766) larvae. Folia Parasitol. 1985;32:127–37.

Pathak KML, Gaur SNS, Sharma SN. The pathology of cysticercus tenuicollis infection in goats. Vet Parasitol. 1982;11:131–9.

Scala A, Urrai G, Varcasia A, Nicolussi P, Mulas M, Goddi L, et al. Acute visceral cysticercosis by Taenia hydatigena in lambs and treatment with praziquantel. J Helminthol. 2016;90:113–6.

Pullin JW. Observations on liver lesions in lambs experimentally infected with the cysticercus of Taenia Hydatigena. Can J Comp Med Vet Sci. 1955;19:17–25.

Christodoulopoulos G, Theodoropoulos G, Petrakos G. Epidemiological survey of cestode-larva disease in Greek sheep flocks. Vet Parasitol. 2008;153:368–73.

Perl S, Edery N, Bouznach A, Abdalla H, Markovics A. Acute severe visceral cysticercosis in lambs and kids in Israel. Isr J Vet Med. 2015;70:49–53.

Scala A, Pipia AP, Dore F, Sanna G, Tamponi C, Marrosu R, et al. Epidemiological updates and economic losses due to Taenia hydatigena in sheep from Sardinia, Italy. Parasitol Res. 2015;114:3137–43.

Deka DK, Gaur SNS. Countercurrent immunoelectrophoresis in the diagnosis of Taenia hydatigena cysticercosis in goats. Vet Parasitol. 1990;37:223–8.

Pathak KML, Gaur SNS, Garg SK. Counter current immunoelectrophoresis, a new technique for the rapid serodiagnosis of porcine cysticercosis. J Helminthol. 1984;58:321–4.

Hossein M, Jalali R, Ghorbanpoor M, Asadollahi Z, Sazmand A. Detection of anti-Cysticercus tenuicollis antibody by counterimmunoelectrophoresis in experimentally infected sheep. Online J Vet Res. 2012;16:133–7.

Panda MR, Ghosh S, Rawat P, Singh NK, Gupta M, Varma TK. Diagnosis of Cysticercus tenuicollis in sheep and goat by indirect ELISA employing oncosphere antigen. Indian J Anim Sci. 2004;74:911–4.

Dore F, Varcasia A, Pipia AP, Sanna G, Pinna Parpaglia ML, Corda A, et al. Ultrasound as a monitoring tool for cystic echinococcosis in sheep. Vet Parasitol. 2014;203:59–64.

Corda A, Tamponi C, Meloni R, Varcasia A, Parpaglia MLP, Gomez-Ochoa P, et al. Ultrasonography for early diagnosis of Toxocara canis infection in puppies. Parasitol Res. 2019;118:873–80.

Nielsen MK, Donoghue EM, Stephens ML, Stowe CJ, Donecker JM, Fenger CK. An ultrasonographic scoring method for transabdominal monitoring of ascarid burdens in foals. Equine Vet J. 2016;48:380–6.

Hussein HA, Elrashidy M. Ultrasonographic features of the liver with cystic echinococcosis in sheep. Vet Rec Open. 2014;1:e000004.

Lahmar S, Chéhida FB, Pétavy AF, Hammou A, Lahmar J, Ghannay A, et al. Ultrasonographic screening for cystic echinococcosis in sheep in Tunisia. Vet Parasitol. 2007;143:42–9.

Doherty ML, McAllister H, Healy A. Ultrasound as an aid to Coenurus cerebralis cyst localisation in a lamb. Vet Rec. 1989;124:591.

DeFrancesco TC, Atkins CE, Miller MW, Meurs KM, Keene BW. Use of echocardiography for the diagnosis of heartworm disease in cats: 43 cases (1985–1997). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2001;218:66–9.

Badertscher RR, Losonsky JM, Paul AJ, Kneller SK. Two-dimensional echocardiography for diagnosis of dirofilariasis in nine dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1988;193:843–6.

Arsenopoulos K, Fthenakis GC, Papadopoulos E. Sonoparasitology: an alternative approach to parasite detection in sheep. Small Rumin Res. 2017;152:162–5.

Athar H, Fazili M ur R, Mir AQ, Gugjoo MB, Ahmad RA, Khan HM. Ultrasonography: an affordable diagnostic tool for precisely locating coenurosis cyst in sheep and goats. Small Rumin Res. 2018;169:19–23.

Cringoli G, Rinaldi L, Maurelli MP, Utzinger J. FLOTAC: New multivalent techniques for qualitative and quantitative copromicroscopic diagnosis of parasites in animals and humans. Nat Protoc. 2010;5:503–15.

Rinaldi L, Coles GC, Maurelli MP, Musella V, Cringoli G. Calibration and diagnostic accuracy of simple flotation, McMaster and FLOTAC for parasite egg counts in sheep. Vet Parasitol. 2011;177:345–52.

Rostami S, Salavati R, Beech RN, Babaei Z, Sharbatkhori M, Baneshi MR, et al. Molecular and morphological characterization of the tapeworm Taenia hydatigena (Pallas, 1766) in sheep from Iran. J Helminthol. 2015;89:150–7.

Scott PR, Sargison ND, Macrae A, Rhind SR. An outbreak of subacute fasciolosis in Soay sheep: Ultrasonographic biochemical and histological studies. Vet J. 2005;170:325–31.

Nyland TG, Larson MM, Mattoon JS. Chapter nine: Liver. In: Mattoon JS, Nyland TG, editors. Small animal diagnostic ultrasound. 3rd ed. St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier Saunders; 2015. p. 343.

vanSonnenberg E, Simeone JF, Mueller PR, Wittenberg J, Hall DA, Ferrucci JT. Sonographic appearance of hematoma in liver, spleen, and kidney: a clinical, pathologic, and animal study. Radiology. 1983;147:507–10.

Abdelaal AM, Abd El Raouf M, Aref MA, Moselhy AA. Clinical and ultrasonographic investigations of 30 water buffaloes (Bubalus bubalis) with hepatomegaly. Vet World. 2019;12:789–95.

Soldati G, Demi M, Smargiassi A, Inchingolo R, Demi L. The role of ultrasound lung artifacts in the diagnosis of respiratory diseases. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2019;13:163–72.

Babkine M, Blond L. Ultrasonography of the bovine respiratory system and its practical application. Vet Clin North Am Food Anim Pract. 2009;25:633–49.

Varcasia A, Tanda B, Giobbe M, Solinas C, Pipia AP, Malgor R, et al. Cystic Echinococcosis in Sardinia: farmers’ knowledge and dog infection in sheep farms. Vet Parasitol. 2011;181:335–40.

Varcasia A, Tamponi C, Tosciri G, Pipia AP, Dore F, Schuster RK, et al. Is the red fox (Vulpes vulpes) a competent definitive host for Taenia multiceps? Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:491.

Paoletti B, Della Salda L, Di Cesare A, Iorio R, Vergara A, Fava C, et al. Epidemiological survey on cystic echinococcosis in wild boar from central Italy. Parasitol Res. 2019;118:43–6.

Sgroi G, Varcasia A, Dessi G, D’Alessio N, Tamponi C, Saarma U, et al. Cystic echinococcosis in wild boars (Sus scrofa) from southern Italy: epidemiological survey and molecular characterization. Int J Parasitol Parasites Wildl. 2019;9:305–11.

Varcasia A, Tosciri G, Sanna Coccone GN, Pipia AP, Garippa G, Scala A, et al. Preliminary field trial of a vaccine against coenurosis caused by Taenia multiceps. Vet Parasitol. 2009;162:285–9.

Kinkar L, Laurimäe T, Acosta-Jamett G, Andresiuk V, Balkaya I, Casulli A, et al. Global phylogeography and genetic diversity of the zoonotic tapeworm Echinococcus granulosus sensu stricto genotype G1. Int J Parasitol. 2018;48:729–42.

Heat D. The life cycle of Echinococcus granulosus—a review. Recent advances in hydatid disease. Victoria: Hamilton Medical Veterinary Association; 1973. p. 7–18.

Pakala T, Molina M, Wu G. Hepatic echinococcal cysts: a review. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2016;4:39–46.

Boufana B, Scala A, Lahmar S, Pointing S, Craig PS, Dessì G, et al. A preliminary investigation into the genetic variation and population structure of Taenia hydatigena from Sardinia, Italy. Vet Parasitol. 2015;214:67–74.

Crilly JP, Politis AP, Hamer K. Use of ultrasonographic examination in sheep veterinary practice. Small Rumin Res. 2017;152:166–73.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Francesco Salis, head technician at the Department of Veterinary Medicine, for his valuable assistance in the laboratory

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: AS, AV, MLPP and AC. Performed the experiments: AC, GD, CT, SC, FS, BM, GS and MS. Analyzed the data: AC, AV, AS, GD, CT, SC and MLPP. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: AS, AV, AC, MLPP, BM and FS. Wrote the paper: AC, AV, AS, MLPP, CT, MS and GD. Collected biological samples: AC, BM, FS, AS, GS, XY and MS. Revised the manuscript: AC, AV, AS, CT and MLPP. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was performed following the recommendations of European Council Directive (86/609/EEC) on the protection of animals.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Corda, A., Dessì, G., Varcasia, A. et al. Αcute visceral cysticercosis caused by Taenia hydatigena in lambs: ultrasonographic findings. Parasites Vectors 13, 568 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-020-04439-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-020-04439-x