Abstract

Background

Because ixodid ticks are vectors of zoonotic pathogens, including Borrelia, information of their abundance, seasonal variation in questing behaviour and pathogen prevalence is important for human health. As ticks are invading new areas northwards, information from these new areas are needed. Taiga tick (Ixodes persulcatus) populations have been recently found at Bothnian Bay, Finland. We assessed seasonal variation in questing abundance of ticks and their pathogen prevalence in coastal deciduous forests near the city of Oulu (latitudes 64–65°) in 2019.

Methods

We sampled ticks from May until September by cloth dragging 100 meters once a month at eight study sites. We calculated a density index (individuals/100 m2) to assess seasonal variation. Samples were screened for Borrelia burgdorferi (sensu lato) (including B. afzelii, B. garinii, B. burgdorferi (sensu stricto) and B. valaisana), Borrelia miyamotoi, Anaplasma phagocytophilum, Rickettsia spp., Neoehrlichia mikurensis, Francisella tularensis and Bartonella spp., Babesia spp. and for the tick-borne encephalitis virus.

Results

All except one nymph were identified as I. persulcatus. The number of questing adults showed a strong peak in May (median: 6.5 adults/100 m2), which is among the highest values reported in northern Europe, and potentially indicates a large population size. After May, the number of questing adults declined steadily with few adults still sampled in August. Nymphs were present from May until September. We found a striking prevalence of Borrelia spp. in adults (62%) and nymphs (40%), with B. garinii (51%) and B. afzelii (63%) being the most common species. In addition, we found that 26% of infected adults were coinfected with at least two Borrelia genospecies, mainly B. garinii and B. afzelii, which are associated with different host species.

Conclusions

The coastal forest environments at Bothnian Bay seem to provide favourable environments for I. persulcatus and the spread of Borrelia. High tick abundance, a low diversity of the host community and similar host use among larvae and nymphs likely explain the high Borrelia prevalence and coinfection rate. Research on the infestation of the hosts that quantifies the temporal dynamics of immature life stages would reveal important aspects of pathogen circulation in these tick populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Zoonotic pathogens transmitted by vectors are increasingly important for human health [1]. In the northern hemisphere, ixodid ticks are the most important vectors for several pathogens of medical and veterinary interest, particularly the TBE-virus (TBEV) and various Borrelia species [2,3,4]. Information on tick population dynamics, seasonal variation in questing behaviour and pathogen prevalence are therefore important for public health. In northern Eurasia, Ixodes ticks have been described to have mainly unimodal or bimodal seasonal patterns around the warmer months of the year [5,6,7,8,9]. However, as their abundance and questing behaviour are dependent on multiple environmental factors [9,10,11], it is difficult to predict seasonal dynamics across the vast ranges of these species - especially when species’ distributions change.

Global warming due to climate change has benefited ixodid species as winters have become more benign and tick activity periods have become longer and warmer in the north [12,13,14,15], the effects of which are evident for example in altitudinal studies [6]. Consequently, tick populations have increased, and their distributions have shifted northwards [14, 16, 17]. As ticks invade new areas and face different environments, their abundance and seasonal questing activity may be different from those in the core areas [5, 10], warranting also localized studies.

One of the main vectors of Borrelia in Eurasia is the taiga tick, Ixodes persulcatus, see [18]. Its distribution currently extends from Fennoscandia to Japan [3, 18]. The taiga tick has been identified in Fennoscandia only recently [19, 20], and this species has been reported to have invaded new areas west- and northwards in northern Europe, up to north-western Finland and eastern Sweden [15, 17]. However, their abundance and seasonal questing behaviour in these newly discovered areas of I. persulcatus establishment have not been examined with standard methods in Finland (but see Laaksonen et al. [17] for a seasonal pattern of ticks collected via a citizen science campaign in Finland). Questing I. persulcatus typically show a rapidly increasing peak in the spring that fades quickly [18], but some seasonal variation can occur [5].

We studied I. persulcatus at the north-western part of their distribution range at Bothnian Bay, Finland (between latitudes 64–65°), with the standard cloth dragging method. We examined (i) the abundance of questing I. persulcatus using a density index, (ii) seasonal variation in questing activity, and (iii) prevalence of a suite of pathogens. We concentrated on coastal deciduous forests because these coastal areas are known to harbour I. persulcatus [15, 17], and because the host communities are often habitat specific causing spatial variation in tick abundance and pathogen prevalence [8, 21,22,23].

Methods

We examined seasonal variation in questing tick abundance at 8 sites on the coast of Bothnian Bay in Finland (65°01′–64°52′N; 24°41′–25°29′E; Fig. 1). These sites were chosen on the basis of earlier information on the existence of ticks (VMP, unpublished observations). The study sites were early successional deciduous forests (Fig. 2), with willows (Salix sp.), reedbed (Phragmites australis) and coastal meadows or pastures separating them from the shoreline. The distance to the shoreline varied from 180 m to 900 m. The forests included mainly birch (Betula pendula) and alder (Alnus incana), but also some European bird cherry (Prunus padus), willows (Salix spp.) and rowan (Sorbus aucuparia). Undergrowth included e.g. dwarf cornel (Cornus suecica), arctic bramble (Rubus arcticus) and different hay species. These coastal areas are very low and flat, and the coastal forests are characterized by standing water tables in early May to June.

Because these areas are covered by snow until late April, we started sampling in May. Each site was sampled once a month. We used the standard cloth dragging method to examine an index for tick density [24]. We dragged a 1 m × 1 m white flannel flag that was connected to a plastic tube. Each sampling occasion included dragging for 100 m on the surface of vegetation. We stopped every 10–15 m to collect ticks into 1.5 ml plastic tubes with 70% ethanol. Each month, we sampled slightly different transects within the same forest fragment. Dragging was done only when it had not been raining on that day and the vegetation was dry. We dragged during the day between 10:00 h and 18:00 h. Air temperature at the time of sampling varied between 9–23 °C. Collected ticks were identified to the species level using morphological keys [25] and/or a duplex qPCR assay targeting the ITS2 region of I. persulcatus and I. ricinus, as described previously [26].

Pathogen analysis

Total DNA and RNA was extracted from tick samples using NucleoSpin® RNA kits and RNA/DNA buffer sets (Macherey-Nagel, Düren Germany), following the kit protocols (NucleoSpin 96 RNA Core Kit: Rev. 05/April 2014 and RNA/DNA buffer set: Rev. 09/April 2017). RNA extracts were stored at − 80 °C for later analyses. DNA extracts were stored at − 20 °C. In addition to the ticks collected from study sites, we also included 7 adults that were collected from an area close to Tömppä, Hailuoto in the analyses.

DNA samples were screened for bacterial pathogens Borrelia burgdorferi (s.l.) (including specific analyses for B. afzelii, B. garinii, B. burgdorferi (s.s.) and B. valaisana), Borrelia miyamotoi, Anaplasma phagocytophilum, Rickettsia spp., Neoehrlichia mikurensis, Francisella tularensis and Bartonella spp., and for protozoan parasites Babesia spp. Furthermore, RNA samples were screened for tick-borne encephalitis virus (TBEV). The primers used for each pathogen are provided in Additional file 1: Tables S1 and S2.

Real-time quantitative PCR (henceforth abbreviated qPCR) assays were carried out using SensiFAST™ Probe Lo-ROX Kit (for DNA) and SensiFAST™ Probe Lo-ROX One-Step Kit (for RNA) (Bioline, Luckenwalde, Germany). All DNA/RNA samples were analyzed in two replicate reactions carried out on 96 or 384-well plates. At least two non-template negative controls (template replaced with distilled water) were used in each assay. The positive controls used are provided in Additional file 1: Text S1. Samples were considered positive when successful amplification was detected in both replicate reactions or in 2 consecutive assays. Assay protocols are reported in the Additional file 1: Text S1.

Samples found positive for Rickettsia by qPCR were subsequently amplified by conventional PCR and Sanger sequenced in order to determine species (Additional file 1: Table S1). Likewise, some B. burgdorferi (s.l.) positive samples that could not be identified to the genospecies level or that gave unconventional signals in qPCR were Sanger sequenced to determine species (Additional file 1: Table S1). Assay protocols and mastermix contents for PCR amplification were as reported previously (for Borrelia: [8]; for Rickettsia: [22]), with the following modifications regarding Borrelia: the reaction volume was increased to 15 µl, with 3 µl DNA template, and the thermal cycling profile was run for 50 cycles with an annealing temperature of 54 °C.

Statistical analysis

We used a generalised linear mixed model (GLMM, binomial errors, logit link) to examine the probability of Borrelia infection (tick infected or not by Borrelia burgdorferi (s.l.) between stages (nymphs vs adults) and linear temporal change across the months from May until September by including the sampling site (8 sites) as a random factor. The model was ran using function ‘glmer’ in package lme4 [27] in R version 3.6.1. [28].

Results

Seasonal variation in the density index

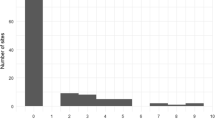

We flagged 4.0 km of transect (8 transects, 100 m2 per month from May until September) and collected altogether 207 I. persulcatus ticks (79 females, 78 males, 40 nymphs and 10 larvae; Additional file 2: Table S3), the ratio being 15.6/4/1 between adults/nymphs/larvae. There was a clear peak in abundance in May, during which densities ranged between 5 and 36 adults per 100 m2, with a median of 6.5 (average of 10.0 ± 3.6 SE) (Fig. 3a, b). After May, their numbers gradually declined until August. The observed activity period of adults lasted 101 days from the 1st May until 9th August. Nymphs were less numerous but their observed activity season lasted 120 days from 10th May until 6th September (Fig. 3a). We observed larvae only in June at 2 sites (Fig. 3b). One of the nymphs collected from Rautaletto, Hailuoto was identified as I. ricinus and was removed from further analyses.

Seasonal variation in abundance of questing I. persulcatus (individuals/100 m2) in coastal deciduous forests at Bothnian Bay, Finland in 2019. a Adults separately for each of the eight sites. b Mean ± standard error (SE) for adults, nymphs and larvae (see Additional file 2: Table S3 for data)

Pathogens

The prevalence of B. burgdorferi (s.l.) was 62% (95% CI: 55–70%) out of 163 sampled adults (males 65%, 95% CI: 54–76%, n = 79; females 60%, 95% CI: 50–70%, n = 84; Additional file 3: Table S4, Additional file 4: Table S5). There was site specific variation in infection rates with Rautaletto in the island of Hailuoto having highest infection rates (Fig. 4a). Out of 40 nymphs, 40% (95% CI: 25–55%) were infected with Borrelia spp. However, no statistically significant differences in Borrelia infection probability between adults and nymphs were found after accounting for variation within months and sites (Table 1, Fig. 4b). Prevalence did not show a linear change across the season (Table 1). None of the larvae (n = 9) were infected.

Borrelia prevalence (± 95 CI) of questing I. persulcatus in coastal deciduous forests at Bothnian Bay, Finland in 2019. a Among adults separately for each of the eight sites. b In general for adults and nymphs. See Fig. 1 for site locations. Abbreviations: HIE, Hietasaari; KEM, Kempeleenlahti; KUI, Kuivasäikkä; PUH, Puhkiavanperä; RAU, Rautaletto; SAV, Savilahti; SÄÄ, Säärenperä; TÖM, Tömppä

The most common B. burgdorferi (s.l.) genospecies were B. garinii (51% of infected adults) and B. afzelii (63% of infected adults), while prevalence was low for B burgdorferi (s.s.) (7%). Only 4% of samples included B. miyamotoi, whereas B. valaisiana was not detected. The distribution of these Borrelia species was similar among infected nymphs (n = 16; B. garinii: 38%; B. afzelii: 50%; B. burgdorferi (s.s.): 6%; B. miyamotoi: 6%). Mixed infections occurred in 26 adults (26% of all infected individuals) but only one (6%) was found among nymphs (Additional file 4: Table S5). These mostly consisted of co-infections between B. garinii and B. afzelii (19 samples). In addition to these, three samples with B. garinii and B. burgdorferi (s.s.), three with B. afzelii and B. miyamotoi, one with B. afzelii and B. burgdorferi (s.s.) and one with B. garinii and B. miyamotoi were detected.

Partial sequencing of the flagellin gene for a subset of B. burgdorferi (s.l.) positive samples revealed four samples of B. garinii that differed from each other by 3–8 bp over the 355 bp product, but were 100% identical to different B. garinii sequences reported from Russia, Japan and China (e.g. one sample with GenBank reference samples LT631698.1, KU672558.1 and CP003151.1). These sequences also differed by 8–10 bp from concurrently sequenced B. garinii obtained from I. ricinus nymphs from Helsinki in southern Finland (Additional file 5: Table S6). In addition, a further three samples from the Bothnian Bay coast with identical sequences were highly similar to two reference B. bavariensis sequences (Additional file 5: Table S6). Borrelia afzelii sequences from the Bothnian Bay (2 unique sequences) were identical to sequences from I. ricinus in Helsinki (12 unique sequences) and a reference sample (GenBank: CP009058.1).

Two adults were infected by A. phagocytophilum and six adults were infected with Rickettsia (5/6 with R. tarasevichiae and 1/6 with R. helvetica). We found no samples positive for TBEV, Bartonella spp., Babesia spp., F. tularensis or N. mikurensis.

Discussion

Questing I. persulcatus showed unimodal seasonal questing behaviour in coastal deciduous forests in the north-western part of its range in northern Finland, with an activity period lasting for at least 101 days. A strong peak in abundance was observed in May, which was followed by a gradual decline, with questing adults still present at low (0.5 individuals/100 m2) densities until August but absent in September. Similar activity patterns have been observed in previous studies concerning I. persulcatus populations from the species core distribution in Russia [18, 29], but in our study the observed peak was higher and the length of the season longer than expected in these northern conditions [5]. However, the length of the questing season may also reflect variation in host availability and the start of behavioural diapause [30]. Questing was most likely initiated in late April after the snow melted [18]. Thus, the risk of tick bites was high starting from late April until June. Importantly, there was also strong geographical variation in questing activity, as some areas also had higher numbers of questing adults in July (Fig. 3a).

The peak density index (median 6.5 and mean 10 ticks per 100 m2) of adults was among the highest reported for I. persulcatus in northern Europe (Table 2). Recent studies from Karelia and western Siberia are closest to the median values observed in our study (Karelia: median 3.5 adults/100 m2, [11]; western Siberia: median 2.7 adults/100 m2, [31]). However, tick densities can show strong spatial variation, as indicated by the particularly high density of I. persulcatus observed on an island nearby at northern Bothnian Bay (75 adults/100 m2; [32]). One of our study sites also displayed a higher tick density than other sites, with 36 adults/100 m2 in May. The densities of adult I. persulcatus observed at these sites in the Bothnian Bay are closer to values reported from the eastern parts of the species’ range [33], but comparison can be difficult due to different methodologies.

While we acknowledge that the tick density estimates obtained by cloth dragging do not give precise approximations of tick population size, the relatively high density-index found in this study that suggests a thriving population is somewhat surprising. This is because the general environmental conditions in the Oulu region are suboptimal in terms of the growing season (155–165 days; https://ilmatieteenlaitos.fi/), cumulative temperature sum is lower (1100–1200 °C) and precipitation (260–320 mm per year), compared to those suggested for taiga ticks [10]. The high density-index may therefore reflect more favourable conditions in the coastal forests. Indeed, I. persulcatus seem to be less abundant further from the coast in northern Finland [17]. At least, the main hosts of adult I. persulcatus, cervids [18] such as moose (Alces alces) and roe deer (Capreolus capreolus) are relatively common in this region.

The high density-index of questing I. persulcatus adults is concurrent with a longer residence at the coast of the Bothnian Bay than currently known. Sightings of blood-sucking ticks have been made from the 1930s onwards by people living in Siikajoki (1960s), Lumijoki (1980s), Hailuoto (1930s), Oulu (1970s) and Ii (1970s; [34, 35], Juha Markkola and Jari Ylönen personal communication). An early examination of tick distribution in Finland in the 1950s, executed as a questionnaire to veterinarians, did not find ticks in this region [36]. It is possible that ticks have been low in abundance during these periods at northern Ostrobothnia and perhaps located mostly within the coastal forests of the Bothnian Bay. However, given the current distribution of I. persulcatus and I. ricinus [17], it is perhaps more likely that these old observations were I. persulcatus rather than I. ricinus. Thus, the recent findings might not reflect recent expansion to this region of the Bothnian Bay, but rather an increase in abundance [19, 20, 37]).

The number of adults was four times that of nymphs, reflecting the limited applicability of cloth dragging in measuring abundance of immature stages of I. persulcatus [18, 33]. Indeed, as opposed to I. ricinus nymphs that are also more easily collected by dragging, I. persulcatus nymphs rarely feed on larger hosts such as humans. Our results nonetheless revealed that the questing season of nymphs was longer than that of the adults, extending until September with a minimum activity period of 120 days.

We found a striking prevalence of Borrelia in I. persulcatus across our study sites: 62% of adults and 40% of nymphs carried Borrelia. These values concur with the generally higher infection rate of I. persulcatus compared to I. ricinus, for which Borrelia prevalence usually varies between 0–45% [38,39,40]. Naturally, Borrelia prevalence is lower in large scale studies that include a variety of environments. For example, a citizen science study, which sampled ticks across Finland, found Borrelia prevalence of about 22% in adult I. persulcatus [4]. Our results from coastal forests therefore stand out significantly. Similar high Borrelia prevalence (up to 69%) has been described among I. persulcatus for some specific localities in larch and larch-birch forests in Russia [41]. Interestingly, a recent study of I. persulcatus populations in the Swedish islands at the Bothnian Bay also reported high Borrelia prevalence (55%; [32]).

High infections rates can be expected among I. persulcatus, as both immature stages feed on small host species that are reservoirs of Borrelia [18]. Similar proportions of B. garinii and B. afzelii infections among adult ticks suggests that both birds and small mammals act as hosts of the immature stages [32]. Such feeding patterns give a plausible explanation for the relatively high coinfection rate of 26% among Borrelia-infected adult ticks that occurred mainly with B. garinii and B. afzelii. Coinfection rates of these genospecies varies (e.g. [42, 43]). Other explanations for coinfections include interrupted feeding [44] and transmission of Borrelia through co-feeding on hosts [45]. Importantly, we also found a low diversity of other tick-borne pathogens. This is consistent with results from the Swedish side of the Bothnian Bay and may indicate a low diversity of host species for the larval and nymph stages [32]. A low host diversity may increase the overall infection rate among adult ticks [46]. These intriguing results warrant further studies on the feeding patterns of I. persulcatus on different hosts and on the Borrelia species infecting their hosts.

Interestingly, flagellin amplicons from a subset of B. burgdorferi (s.l.) positive samples revealed conserved B. afzelii sequences but varying B. garinii sequences, both within the coastal areas of the Bothnian Bay as well as between different areas in Finland. While none of the B. garinii sequences obtained from I. persulcatus were identical, they displayed 100% identity matches with various sequences reported from Russia, Japan and China, which consequently also appear to mostly originate from I. persulcatus. This suggests the possible presence of an eastern and/or I. persulcatus associated strain (or strains). In contrast, nine identical B. garinii sequences were attained from nine I. ricinus nymphs collected from different areas in Helsinki. It remains to be determined whether the apparent existence of different B. garinii/B. garinii-like strains in the Bothnian Bay coast and Helsinki is a consequence of some tick species specific factor or, for example, geographical variation in available host animal species. Whatever the cause, these observations are in line with recently reported observations from across Europe, which revealed that little geographical structuring within B. garinii strains can be detected [47]. This is expected to be at least partly on account of their highly mobile avian reservoir hosts, which may effectively and quickly transfer different strains across vast geographical ranges.

In addition, a further three sequences from the Bothnian Bay were found to be identical with each other and highly similar to two reference samples of B. bavariensis. Borrelia bavariensis is a genospecies closely associated with B. garinii, which has not been reported from Finland thus far [48]. Unfortunately, due to their close likeness, the reliable differentiation of B. bavariensis and B. garinii requires more thorough molecular methods, such as multilocus sequence analysis [48]. Consequently, the possible presence of B. bavariensis samples reported as B. garinii in GenBank also cannot be discounted, further complicating the identification of the genospecies, particularly based on sequences of a single target gene. As such, the precise identity of these three B. bavariensis-like samples remains undetermined. In any case, the occurrence of these different B. garinii/B. bavariensis-like bacteria at the Bothnian Bay may explain why the genospecies-specific qPCR analyses gave missing or abnormal signals in their case.

Conclusions

We show a relatively high peak abundance of questing I. persulcatus in May at the north-western part of their distribution, along with gradually declining questing activity towards the autumn. Overall, the activity period of I. persulcatus lasted until August among adults and until September among nymphs. Furthermore, this I. persulcatus population had a very high prevalence of Borrelia but low diversity of other pathogens. Taken together, our results suggest that these coastal forest environments may provide favourable environments for reproduction and survival of I. persulcatus, and the spread of Borrelia.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its additional files. Representative sequences were deposited in the GenBank database.

Abbreviations

- TBEV:

-

The tick-borne encephalitis virus

- GLMM:

-

Generalized linear mixed model

References

Kilpatrick AM, Randolph SE. Drivers, dynamics, and control of emerging vector-borne zoonotic diseases. Lancet. 2012;380:1946–55.

Gray J. Review the ecology of ticks transmitting Lyme borreliosis. Exp Appl Acarol. 1998;22:249–58.

Swanson SJ, Neitzel D, Reed KD, Belongia EA. Coinfections acquired from Ixodes ticks. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:708–27.

Laaksonen M, Klemola T, Feuth E, Sormunen JJ, Puisto A, Mäkelä S, et al. Tick-borne pathogens in Finland: comparison of Ixodes ricinus and I. persulcatus in sympatric and parapatric areas. Parasit Vectors. 2018;11:556.

Korenberg EI. Seasonal population dynamics of Ixodes ticks and tick-borne encephalitis virus. Exp Appl Acarol. 2000;24:665–81.

Qviller L, Grøva L, Viljugrein H, Klingen I, Mysterud A. Temporal pattern of questing tick Ixodes ricinus density at differing elevations in the coastal region of western Norway. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:179.

Korotkov Y, Kozlova T, Kozlovskaya L. Observations on changes in abundance of questing Ixodes ricinus, castor bean tick, over a 35-year period in the eastern part of its range (Russia, Tula region). Med Vet Entomol. 2015;29:129–36.

Sormunen JJ, Klemola T, Vesterinen EJ, Vuorinen I, Hytönen J, Hänninen J, et al. Assessing the abundance, seasonal questing activity, and Borrelia and tick-borne encephalitis virus (TBEV) prevalence of Ixodes ricinus ticks in a Lyme borreliosis endemic area in Southwest Finland. Ticks Tick-Borne Dis. 2016;7:208–15.

Cayol C, Koskela E, Mappes T, Siukkola A, Kallio ER. Temporal dynamics of the tick Ixodes ricinus in northern Europe: epidemiological implications. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10:166.

Sirotkin MB, Korenberg EI. Influence of abiotic factors on different developmental stages of the taiga tick Ixodes persulcatus and the sheep tick Ixodes ricinus. Entomol Rev. 2018;98:496–513.

Bugmyrin S, Bespyatova L, Korotkov Yu. Long-term dynamics of Ixodes persulcatus (Acari: Ixodidae) abundance in the north-west of its range (Karelia, Russia). Exp Appl Acarol. 2019;77:229–40.

Lindgren E, Talleklint L, Polfeldt T. Impact of climatic change on the northern latitude limit and population density of the disease-transmitting European tick Ixodes ricinus. Environ Health Perspect. 2000;108:119–23.

Gray JS, Dautel H, Estrada-Peña A, Kahl O, Lindgren E. Effects of climate change on ticks and tick-borne diseases in Europe. Interdiscip Perspect Infect Dis. 2009;2009:593232.

Jaenson TG, Jaenson DG, Eisen L, Petersson E, Lindgren E. Changes in the geographical distribution and abundance of the tick Ixodes ricinus during the past 30 years in Sweden. Parasit Vectors. 2012;5:8.

Jaenson TG, Varv K, Frojdman I, Jääskelainen A, Rundgren K, Versteirt V, et al. First evidence of established populations of the taiga tick Ixodes persulcatus (Acari: Ixodidae) in Sweden. Parasit Vectors. 2016;9:377.

Tokarevich NK, Tronin AA, Blinova OV, Buzinov RV, Boltenkov VP, Yurasova ED, et al. The impact of climate change on the expansion of Ixodes persulcatus habitat and the incidence of tick-borne encephalitis in the north of European Russia. Global Health Act. 2011;4:8448.

Laaksonen M, Sajanti E, Sormunen JJ, Penttinen R, Hänninen J, Ruohomäki K, et al. Crowdsourcing-based nationwide tick collection reveals the distribution of Ixodes ricinus and I. persulcatus and associated pathogens in Finland. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2017;6:e31.

Uspensky I. The taiga tick Ixodes persulcatus (Acari: Ixodidae), the main vector of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in Eurasia, in Lyme disease. Dove: SMGroup; 2016. smgebooks.com/lymedisease/chapters/LD-16-02.pdf.

Jääskeläinen AE, Tikkakoski T, Uzcategui NY, Alekseev AN, Vaheri A, Vapalahti O. Siberian subtype tick-borne encephalitis virus, Finland. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:1568–71.

Jääskeläinen AE, Tonteri E, Sironen T, Pakarinen L, Vaheri A, Vapalahti O. European subtype tick-borne encephalitis virus in Ixodes persulcatus ticks. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:323–5.

Ruiz-Fons F, Fernandez-de-Mera IG, Acevedo P, Gortázar C, de la Fuente J. Factors driving the abundance of Ixodes ricinus ticks and the prevalence of zoonotic, I. ricinus-borne pathogens in natural foci. Appl Environ. Microbiol. 2012;78:2669–76.

Sormunen JJ, Klemola T, Hänninen J, Mäkelä S, Vuorinen I, Penttinen R, et al. The importance of study duration and spatial scale in pathogen detection—evidence from a tick-infested island. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2018;7:189.

Ehrmann S, Ruyts SC, Scherer-Lorenzen M, Bauhus J, Brunet J, Cousins SAO, et al. Habitat properties are key drivers of Borrelia burgdorferi (s.l.) prevalence in Ixodes ricinus populations of deciduous forest fragments. Parasit Vectors. 2018;11:23.

Sonenshine D. Ecological dynamics of tick-borne zoonoses. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1994.

Estrada-Peña A, Mihalca AD, Petney TN. Ticks of Europe and North Africa: a guide to species identification. Cham: Springer; 2018.

Sormunen JJ, Penttinen R, Klemola T, Hänninen J, Vuorinen I, Laaksonen M, et al. Tick-borne bacterial pathogens in southwestern Finland. Parasit Vectors. 2016;9(168):27.

Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker B, Walker S. Fitting linear mixed effects models using lme4. J Stat Softw. 2015;67:1–48.

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2019.

Zemskaya AA. Seasonal activity of adult ticks Ixodes persulcatus P. Sch in the eastern part of the Russian plain. Folia Parasitol. 1984;31:269–76.

Gray JS, Kahl O, Lane RS, Levin ML, Tsao JI. Diapause in ticks of the medically important Ixodes ricinus species complex. Ticks Tick Dis. 2016;7:992–1003.

Romanenko V, Leonovich S. Long-term monitoring and population dynamics of ixodid ticks in Tomsk city (western Siberia). Exp Appl Acarol. 2015;66:103–18.

Jaenson TGT, Wilhelmsson P. First records of tick-borne pathogens in populations of the taiga tick Ixodes persulcatus in Sweden. Parasit Vectors. 2019;12:559.

Uchikawa K. Seasonal fluctuations of Ixodes persulcatus and adult stage of Ixodes ovatus in the subalpine forests of Nagano Prefecture, Japan, related to observed phenological data (Acari, Ixodidae). Jpn J Sanit Zool. 1993;44:203–11.

Markkola J, Merilä E, Salonen H. Puutiaisia Rautaletossa. Hailuodon Luonto. 1987;2:26.

Markkola J, Merilä E. Hailuodon Ison Matalan - Härkäsäikän luonnonsuojelualueen käyttö- ja hoitosuunnitelmaehdotus. Oulu: Conservation of Liminganlahti Wetland Life-Nature project; 1998.

Öhman C. The geographical and topographical distribution of Ixodes ricinus in Finland. Acta Soc Fauna Flora Fennica. 1961;76:1–37.

Alekseev AN, Dubinina HV, Jääskeläinen AE, Vapalahti O, Vaheri A. First report on tick-borne pathogens and exoskeletal anomalies in Ixodes persulcatus schulze (Acari: Ixodidae) collected in Kokkola coastal region, Finland. Int J Acarol. 2007;33:253–8.

Korenberg EI, Kovalevskii YV, Levin ML, Shchyogoleva TV. The prevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in Ixodes persulcatus and I. ricinus ticks in the zone of their sympatry. Folia Parasitol. 2001;48:63–8.

Strnad M, Hönig V, Růžek D, Grubhoffer L, Rego RO. Europe-wide meta-analysis of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato prevalence in questing Ixodes ricinus ticks. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2017;83:e00609–17.

Estrada-Peña A, Cutler S, Potkonjak A, Vassier-Tussaut M, van Bortel W, Zeller H, et al. An updated meta-analysis of the distribution and prevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi s.l. in ticks in Europe. Int J Health Geogr. 2018;17:41.

Pukhovskaya NM, Morozova OV, Vysochina NP, Belozerova NB, Ivanov LI. Prevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato and Borrelia miyamotoi in ixodid ticks in the Far East of Russia. Int J Parasitol Parasites Wildl. 2019;8:192–202.

Misonne MC,Van Impe G, Hoet PP. Genetic heterogeneity of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in Ixodes ricinus ticks collected in Belgium. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:3352–4.

Moutailler S, Valiente Moro C, Vaumourin E, Michelet L, Tran FH, Devillers E, et al. Co-infection of ticks: the rule rather than the exception. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10:e0004539.

Richter D, Debski A, Hubalek Z, Matuschka FR. Absence of Lyme disease spirochetes in larval Ixodes ricinus ticks. Vector-Borne Zoonot. 2012;12:21–7.

Gern L, Rais O. Efficient transmission of Borrelia burgdorferi between cofeeding Ixodes ricinus ticks (Acari: Ixodidae). J Med Entomol. 1996;33:189–92.

Turney S, Gonzalez A, Millien V. The negative relationship between mammal host diversity and Lyme disease incidence strengthens through time. Ecology. 2014;95:3244–50.

Norte AC, Margos G, Becker NS, Ramos JA, Núncio MS, Fingerle V, et al. Host dispersal shapes the population structure of a tick-borne bacterial pathogen. Mol Ecol. 2020;29:485–501.

Margos G, Wilske B, Sing A, Hizo-Teufel C, Cao WC, Chu C, et al. Borrelia bavariensis sp. nov. is widely distributed in Europe and Asia. Int J Syst Evol Micr. 2013;63:4284–8.

Bugmyrin S, Hokkanen TJ, Romanova L, Bespyatova L, Fyodorov F, Burenkova L, et al. Ixodes persulcatus (Schulze, 1930) (Acari: Ixodidae) in eastern Finland. Entomol Fennica. 2011;22:268–73.

Bugmyrin SV, Bespyatova LA, Korotkov YS, Burenkova LA, Belova OA, Romanova LI, et al. Distribution of Ixodes ricinus and I. persulcatus ticks in southern Karelia (Russia). Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2013;4:57–62.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Ella-Maria Vesilahti and Satu Mäkelä for their help with the laboratory analyses.

Funding

JS received funding from the Jane and Aatos Erkko Foundation and the Maj and Tor Nessling Foundation. DB received funding from Stiftelsen Olle Enqvist Byggmästare and ERK from the Academy of Finland (329332 and 329308).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

VMP, DB and ERK designed the study. VMP collected the field data. JS and ES conducted the laboratory analyses. VMP, JS, DB and ERK took part in data analysis and interpretation of results. VMP took the lead in writing and all authors took part in writing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Text S1.

Additional laboratory protocols. Table S1. Primers and probes used in tick-borne pathogen screening and sequencing. Table S2. Mastermix contents for qPCR analyses of tick-borne pathogens.: Text S1. Additional laboratory protocols. Table S1. Primers and probes used in tick-borne pathogen screening and sequencing. Table S2. Mastermix contents for qPCR analyses of tick-borne pathogens.

Additional file 2: Table S3.

Data on the number collected ticks per 100 m2. Information sampling days and sites with coordinates and the stage of collected ticks and the sex of adults.

Additional file 3: Table S4.

Data on pathogen infections for each individual.

Additional file 4: Table S5.

Data on pathogen infections summarised per area and stage (adults vs nymphs).

Additional file 5: Table S6.

Comparative analysis of Borrelia flagellin sequences from I. persulcatus adults from the Bothnian Bay coast (samples labeled BothnianB), I. ricinus nymphs from Helsinki (Helsinki) and reference sequences downloaded from GenBank (with accession numbers). Numbers in brackets signify the count of unique, identical sequences. Geneious version 2020.0 created by Biomatters. Available from https://www.geneious.com.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Pakanen, VM., Sormunen, J.J., Sippola, E. et al. Questing abundance of adult taiga ticks Ixodes persulcatus and their Borrelia prevalence at the north-western part of their distribution. Parasites Vectors 13, 384 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-020-04259-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-020-04259-z