Abstract

Background

Coccidiosis is recognised as a major parasitic disease in chickens. Eimeria maxima is considered as a highly immunoprotective species within the Eimeria spp. family that infects chickens. In the present research, the surface antigen gene of E. maxima (EmSAG) was cloned, and the ability of EmSAG to stimulate protection against E. maxima was evaluated.

Methods

Prokaryotic and eukaryotic plasmids expressing EmSAG were constructed. The EmSAG transcription and expression in vivo was performed based on the RT-PCR and immunoblot analysis. The expression of EmSAG in sporozoites and merozoites was detected through immunofluorescence analyses. The immune protection was assessed based on challenge experiments. Flow cytometry assays were used to determine the T cell subpopulations. The serum antibody and cytokine levels were evaluated by ELISA.

Results

The open reading frame (ORF) of EmSAG gene contained 645 bp encoding 214 amino acid residues. The immunoblot and RT-PCR analyses indicated that the EmSAG gene were transcribed and expressed in vivo. The EmSAG proteins were expressed in sporozoite and merozoite stages of E. maxima by the immunofluorescence assay. Challenge experiments showed that both pVAX1-SAG and the recombinant EmSAG (rEmSAG) proteins were successful in alleviating jejunal lesions, decreasing loss of body weight and the oocyst ratio. Additionally, these experiments possessed anticoccidial indices (ACI) of more than 170. Higher percentages of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were detected in both EmSAG-inoculated birds than those of the negative control groups (P < 0.05). The EmSAG-specific antibody concentrations of both the rEmSAG and pVAX1-EmSAG groups were much higher than those of the negative controls (P < 0.05). Higher concentrations of IL-4, IFN-γ, TGF-β1 and IL-17 were observed more in both the rEmSAG protein and pVAX1-SAG inoculated groups than those of negative controls (P < 0.05).

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that EmSAG is capable of eliciting a moderate immune protection and could be used as an effective vaccine candidate against E. maxima.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Coccidiosis is recognised as a major parasitic disease in chickens seriously affecting the efficiency of feed conversion and leading to decreased production. Eimeria maxima has been recognised as one of the most economically significant species of Eimeria [1]. Currently, prophylactic chemotherapy with anticoccidial drugs is the major control strategy for coccidiosis. Traditional anticoccidial drugs and live vaccines have their own defect [2]. Subunit vaccines encoding the Eimeria proteins which stimulated protective immunity were accepted as effective vaccines against coccidiosis [3,4,5]. Recently, many reports have shown that cell-mediated immunity could be stimulated by DNA vaccines [6,7,8,9,10].

Surface antigens have been proven to confer protection against coccidiosis by altering key processes in host cell invasions [11]. The SAGs protein of Eimeria tenella is capable of inducing an immune response against coccidiosis in chickens [12]. Therefore, surface antigens and cell adhesion proteins have been suggested as promising vaccine candidates against parasitic infections [13, 14].

Eimeria maxima is regarded as a highly immunoprotective species within the family of Eimeria spp. affecting chickens [15,16,17,18,19]. In this study, subunit and DNA vaccines made from EmSAG were evaluated for their protection against E. maxima.

Methods

Chickens and parasites

Eimeria-free birds at one day of age were reared in captivity with provided water and feed ad libitum. The birds were placed in a coccidia-free environment. The Jiangsu strain of E. maxima was developed and maintained in Eimeria-free birds our laboratory. Sporozoites from E. maxima oocysts were cleaned and sporulated as previously described [20].

Amplification and prokaryotic expression of EmSAG

The construction of prokaryotic expression of EmSAG was conducted as previously described [20]. Briefly, the EmSAG-encoding sequence (GenBank: XM_013482011.1) was amplified by PCR. EmSAG-specific primers were utilised for the PCR assays: SAG1 (forward primer: 5'-CGC GGA TCC GAC ACA ATC TCC AGC CCT-3'; BamHI restriction sites underlined) and SAG2 (reverse primer: 5'-ATT GCG GCC GCT CAA ATG AGA ACA GAT GCG-3'; NotI restriction sites underlined) with E. maxima cDNA as a template. The amplification products of EmSAG cloned in pMD-19T (TaKaRa, Dalian, China) resulted in the formation of recombinant plasmid pMD-19T-EmSAG. Subsequently, the EmSAG gene was inserted into the pET-32a (+) (Novagen, Madison, WI, USA) frame of expression vector system and confirmed by endonuclease digestion. Following sequence analysis (Invitrogen Biotech, Shanghai, China) and verification, the positive clones were confirmed as pET-32a/ EmSAG.

Expression of the recombinant EmSAG protein

The sequence identity of EmSAG was compared to the known SAG sequences of other Eimeria spp. and assessed using the BLASTx and BLASTp search tools (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). The amino acid sequence of EmSAG was used to predict N-terminal signal peptides through a bioinformatics online program (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP/). The cladogram was made using the MEGA 6.0 programme with the neighbour-joining method. The pET-32a/EmSAG was expressed in E. coli BL21 (DE3) as described previously [21]. The recombinant protein was purified and the concentration of the sample was determined using the Bradford method [22]. The rEmSAG protein was kept frozen (-70 °C) until further analysis.

Development of anti-EmSAG antibodies against the rEmSAG protein

Rat polyclonal anti-EmSAG antibodies were generated in the Sprague-Dawley rats at 4 weeks of age. Rats were subcutaneously immunised with a total of 0.3 mg of rEmSAG protein mixed with Freund’s complete adjuvant. Fourteen days after the first immunisation, the rats were given a booster injection with 0.3 mg of rEmSAG protein in Freund’s incomplete adjuvant. Three booster doses were given at 1-week intervals. Finally, rat serum containing antibodies were obtained after the last booster injection and kept frozen (at -70 °C) until subsequent analysis. Pre-immunisation serum was obtained for later use as the negative control [23].

Construction of eukaryotic plasmid of EmSAG

The construction of eukaryotic plasmid of EmSAG was conducted and purified as previously described [20]. Briefly, the EmSAG fragment was inserted into the pVAX1, following the sequence analysis (Invitrogen Biotech) and verification, the positive clones were confirmed as pVAX1-EmSAG. The plasmids encoding EmSAG were extracted using EndoFree Plasmid MEGA Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). The concentration of the sample was determined using as per the method suggested earlier [20]. Finally, the plasmids were kept frozen (-20 °C) until subsequent analysis.

Immunoblot analysis of native EmSAG and rEmSAG proteins

Immunoblot analyses for rEmSAG and native EmSAG were performed as described in an earlier work [20]. Rat anti-rEmSAG sera (dilutions of 1:200) were used to detect sporozoites. Chicken anti-E. maxima sera (dilutions of 1:100) were used to detect the rEmSAG protein. Goat anti-rat HRP-IgG and donkey anti-chick HRP-IgG (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) were used as a secondary antibody.

Transcription and expression of pVAX1-EmSAG in vivo

The EmSAG transcription in vivo was performed based on the RT-PCR and immunoblot analysis, as previously described [24]. Briefly, in coccidia-free chickens, a total of 100 μg pVAX1-EmSAG plasmid was intramuscularly injected into the legs. In the pVAX1 control group, the 100 μg pVAX1 plasmid was injected into the legs. One week post-immunisation, the tissues from vaccinated and non-vaccinated chickens were collected for both RT-PCR and immunoblot analyses. EmSAG-specific primers were utilised for the RT-PCR assays. Rat anti-rEmSAG sera (dilutions of 1:200) were used to detect pVAX1-EmSAG expression. The secondary antibody was HRP-conjugated goat anti-rat IgG (Sigma-Aldrich).

Location of the EmSAG protein in sporozoites and merozoites stages

Immunofluorescence technique was used to locate EmSAG in sporozoites and merozoites as previously described [25]. Nuclei were probed with 2-(4-amidinophenyl)-6-indole carbamidinedihydrochloride (DAPI, Sigma-Aldrich). Rat anti-EmSAG sera (1:100 dilutions) were used as the primary antibody. The secondary antibody was Cy3-conjugated goat anti-rat IgG (Beyotime, Haimen, Jiangsu, China) (dilution of 1:1000). The slides were analysed using fluorescence microscopy (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

Experimental design

Chickens at 14 days of age, negative for Eimeria were placed in six groups, each including 30 birds. The chickens were inoculated intramuscularly injection with the pVAX1-SAG (100 μg/chick) or rEmSAG protein (200 μg/chick). In the pVAX1 control chickens, a total of 100 μg pVAX1 plasmid was injected into the legs. In the pET-32a control chickens group, a total of 200 μg pET-32a protein was injected as above. The challenged and unchallenged control birds were immunised with PBS. One week later, the birds were boosted with the same route as the primary immunisation. Subsequently, 7 days after the last immunisation, 1 × 105 sporulated oocysts of E. maxima were given to all the birds except the negative control birds. Seven days later, the birds were euthanised to measure their immune response and degree of coccidial protection. Moreover, the birds (n = 5 per group) were placed in another coccidia-free room. Finally, 10 days after the last immunisation, the serum samples were harvested and kept frozen (-20 °C) until further antibodies and cytokine production analysis could be conducted.

Assessment of immune protection

The chickens were monitored for body weight gain and signs of immune protection (jejunal lesion score, survival rate and change in oocyst ratio). Lesion scrapings were microscopically examined for any coccidia, whenever there was doubt of truly coccidia-induced lesions. The jejunal lesion scores of the birds were also evaluated, as described in previous research [23]. The body weight gains were measured at different time-points: the days of vaccination, at the time of the coccidia challenge, and at the end of the test. All the jejunal contents from each bird were harvested and used to evaluate the oocyst counts as described in a previous study [26]. Using the McMaster’s counting method, oocysts and the oocyst ratio were assessed as previously described [27]. Anticoccidial index (ACI) values were evaluated as per the standard formula for assessing protection against E. maxima [20].

ELISA analysis of the serum antibody and cytokine

EmSAG-specific IgY/IgG antibodies were detected by ELISA using the rEmSAG protein as a coating antigen, following previous protocols [28]. The serum samples (1:50 dilution) were detected using the secondary antibodies of donkey anti-chicken HRP-conjugated IgG monoclonal antibody (Sigma-Aldrich). The experiment was completed in duplicate.

For cytokines level analysis, serum samples were obtained and measured as previously described [29]. Briefly, 10 days after the last inoculation, the serum samples of the birds (n = 5) per group were harvested to evaluate the cytokines. The titers of IL-4, IL-17, IFN-γ and TGF-β1 were measured using ELISA kits (CUSABIO, Wuhan, China). The data was pooled from three independent experiments.

Determination of T-cell response

The counts of T cells in the treatment groups were evaluated by flow cytometry analysis as previously described [30, 31]. Spleens were extracted from 5 chickens of each group at pre-, first-, and second-vaccination days. Lymphocytes were obtained from the spleens were stained with SPRD-conjugated CD3 monoclonal antibodies. The cells were then probed with PE-conjugated mouse monoclonal anti-chicken CD4 or the PE-conjugated mouse monoclonal anti-chicken CD8 (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Birmingham, AL, USA). Using FACS flow cytometer, the stained cells were analysed with Cell Quest software (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA).

Statistical analysis

All data was expressed as the mean ± standard deviation using the SPSS Statistical Software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The data were analysed with one-way ANOVA using Duncan’s post-hoc test and considered to be statistically significant at P < 0.05.

Results

EmSAG sequence analysis

Using E. maxima cDNA as a template, the PCR product of EmSAG was isolated and ligated with pMD19-T. Sequence analysis showed that the EmSAG ORF encoded a protein of 24.73 kDa with a pI of 4.808. As shown in Fig. 1, the phylogenetic tree formulation indicated that the kinship of EmSAG protein was highly related to the EtTA4 and EnNA4 when compared with other Eimeria spp. (E. mitis, E. brunetti, E. praecox, E. acervulina and E. necatrix). The amino acid sequence was analysed with the SignalP programme. The findings suggested an obvious signal peptide possessed a cleavage site between position 21 and 22.

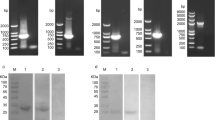

Purification of the rEmSAG protein

The pET32a/EmSAG plasmids were expressed in E. coli BL21. After IPTG induction, the rEmSAG proteins were harvested. The purified fusion rEmSAG protein was approximately 43 kDa (Fig. 2). This calculated total value of 43 kDa was considered accurate as the sum of both the approximate 20 kDa length of pET-32a (+) and the approximate 23 kDa length of the EmSAG protein.

Immunoblot analysis of native and rEmSAG proteins

The native and rEmSAG proteins were evaluated by the western blot method (Fig. 3). The rEmSAG protein was tested using chicken E. maxima-specific antibodies, but not by the antibodies of unimmunised chickens. Furthermore, the western blot assay also showed a band of almost 26 kDa belonging to the sporozoites protein detected by rat anti-rEmSAG antibodies (Fig. 3), in contrast to the serum from the negative control rats that did not display any bands.

Immunoblot analysis for native and rEmSAG proteins. Lane M: pre-stained protein marker; Lane 1: rEmSAG recognised by chick anti-E. maxima serum; Lane 2: rEmSAG protein tested against unimmunised chicken sera; Lane 3: E. maxima protein from sporozoites detected by rat anti-rEmSAG sera; Lane 4: protein of E. maxima sporozoites detected by unimmunised rat sera

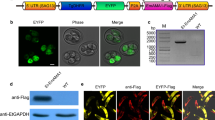

Identification of EmSAG location in sporozoites and merozoites

The location of EmSAG in sporozoites and merozoites of E. maxima was confirmed using immunofluorescence analyses (Fig. 4). The EmSAG protein was detected using rat anti-rEmSAG antibodies, and Cy3-conjugated goat anti-rat IgG as secondary antibodies shown in red fluorescence, whereas no red fluorescence was detected in cells probed with the pre-immune rat serum. The nuclei of the sporozoites and merozoites were visualised as blue. These results suggest that EmSAG was expressed in both the sporozoite and merozoite stages of E. maxima.

Expression of EmSAG protein in sporozoites and merozoites at 100× magnification. a The sporozoites were detected by rat anti-rEmSAG antibodies. a1 Sporozoites were dyed by Cy3. a2 The nuclei were probed by DAPI. a3 Overlaps of Cy3 and DAPI. b The sporozoites were detected by unimmunised rat antibodies. b1 Cy3 stains. b2 DAPI stains. b3 Merge. c Merozoites were detected by rat anti-rEmSAG antibodies. c1 Cy3 stains. c2 DAPI stains. c3 Merge. d The merozoites were detected by unimmunised rat antibodies. d1 Cy3 stains. d2 DAPI stains. d3 Merge. Scale-bars: 10 μm

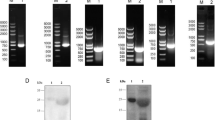

Identification of transcription and expression of pVAX1-EmSAG in vivo

Transcription and expression of pVAX1-SAG in vivo was evaluated through RT-PCR, using the EmSAG-specific primers. A specific DNA band was detected belonging to pVAX1-EmSAG in the tissues of the injected site (Fig. 5a, Lane 4). The RNA samples from non-inoculated and pVAX1-inoculated tissues did not detect any band in the RT-PCR analyses (Fig. 5a, Lanes 1, 2 and 3).

Expression and transcription of pVAX1-SAG in vivo were identified through RT-PCR and western blot assays. a RT-PCR of pVAX1-EmSAG transcription in chicken muscle. Lane M: DNA marker DL2000; Lanes 1 and 2: the muscle RNA sample from the non-inoculated chicken; Lane 3: the muscle RNA sample from the pVAX1-inoculated chicken; Lane 4: the muscle RNA sample from the pVAX1-EmSAG injected chicken. b Western blot of pVAX1-EmSAG in chicken muscle. Lane M: pre-stained protein marker; Lane 1: the protein sample from pVAX1-inoculated chickens; Lane 2: the protein sample from pVAX1- EmSAG inoculated chickens

In addition, expression of pVAX1-SAG in vivo was detected through immunoblot analysis. A unique band of approximately 26 kDa was detected in the pVAX1-EmSAG-vaccinated muscle sample. In contrast, no band was shown in the pVAX1-immunised muscle samples (Fig. 5b). These results indicate the successful transcription and expression of the EmSAG gene in vivo.

Determination of IgY/IgG and cytokines levels using ELISA

To evaluate the titers of IgY/IgG and the cytokines, serum samples from the immunised birds (n = 5 per group) were harvested at 10 days after the last vaccination. The anti-EmSAG IgY/IgG titers of each group are shown in Fig. 6. The IgY/IgG titers of both EmSAG-immunised groups were much higher (ANOVA, F(4, 20) = 77.78, P < 0.0001) compared to the controls.

The titers of cytokines were measured using ELISA (Fig. 7). The serum samples in both pVAX1-EmSAG and rEmSAG-immunised chickens displayed higher titers of IFN-γ (ANOVA, F(4, 20) = 43.59, P < 0.0001), IL-17 (ANOVA, F(4, 20) = 42.25, P < 0.0001), IL-4 (ANOVA, F(4, 20) = 3.25, P = 0.033) and TGF-β1 (ANOVA, F(4, 20) = 48.12, P < 0.0001) compared to the negative controls.

Analysis of T cell subpopulations

To evaluate the EmSAG specific T-cell responses, flow cytometry assays were used to analyse the CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. The spleen lymphocytes were collected at pre-, first-, and second-inoculation time-points (Fig. 8). After the last vaccination, the percentage of CD4+ in the EmSAG-immunised chickens was higher (ANOVA, F(4, 20) = 46.28, P < 0.0001), than those in the PBS group, pVAX1.0 group, and the pET-32a (+) group. Regarding CD8+ T cells, EmSAG groups showed a higher (ANOVA, F(4, 20) = 43.59, P < 0.0001) percentage, whereas the PBS, pVAX1 and pET-32a (+) control group remained at low levels after the second immunisation (Table 1 and Fig. 8).

Immune protection of EmSAG against E. maxima

To analyse the immune protection of EmSAG against E. maxima, the challenge experiments were assessed. The degrees of immune protection conferred by vaccinations of pVAX1-EmSAG and rEmSAG proteins were measured, and the results of ACI are described in Table 2. Birds inoculated with EmSAG exhibited higher weight gains (ANOVA, F(5, 174) = 27.67, P < 0.0001) and greater decreases in oocyst ratios when compared to all other groups. The ACIs of the EmSAG-immunised chickens were more than 170, providing moderate protective immunity.

Discussion

In this research, both DNA and recombinant protein vaccines encoding EmSAG of E. maxima were compared regarding their abilities to induce protection against E. maxima infection. These results indicated that inoculation with EmSAG could promote IgG levels in the sera and upregulated the titers of IL-4, IFN-γ, IL-17 and TGF-β1. Furthermore, the data from the animal experiments proved that EmSAG-immunised groups could produce ACIs of more than 170. Taken together, these data demonstrate that EmSAG vaccines could stimulate moderate protection against E. maxima.

DNA and recombinant protein vaccines were reported to induce immuno-protection to live parasite challenge. Higher body weight gain, lower fecal oocyst shedding and reduced intestinal pathology were detected for immune protection. Jang et al. [32] reported that birds had lower oocyst concentration in droppings and reduced intestinal pathology after vaccination with Gam82 and challenged with E. maxima when compared with non-vaccinated and parasite-challenged groups. Xu et al. [33] determined that pcDNA3.0-TA4-IL-2 could decrease caecal lesions and body weight loss as well as produce an ACI of 192. Song et al. [34] reported that chickens immunised with pMP13 plasmid showed significantly lower number of oocysts following the challenge with E. acervulina compared to those in the negative controls. Similar results were detected in this study, both pVAX1-EmSAG and rEmSAG vaccines were successful in alleviating jejunal lesions, decreasing loss of body weight and the oocyst ratio.

The chick-anti-Eimeria specific antibodies have been previously documented to provide minor protection against coccidiosis. However, humoral immunity may also contribute to the formation of protective immune responses [35]. Furthermore, Wallach [36] pointed out that antibodies could inhibit parasite development and provide passive immune protection. Lin et al. [37] reported that birds immunised with the E. tenella rEF-1α protein exhibited higher specific antibodies concentration than the negative controls. In this research, the antibody titers of the EmSAG-immunised animals were higher than the negative controls. The findings of this investigation confirmed that EmSAG could induce humoral immune response.

IFN-γ is an important cytokine involved in the Th1-mediated immune response. Chicken IFN-γ could elicit lymphocytes and enhance expression of MHC class II antigens [38]. IFN-γ could also reduce sporozoites development without affecting the sporozoite invasion of host cells [39]. In previous research, higher titers of IFN-γ were detected in the EmMIC7 vaccinated birds [20]. In this study, higher IFN-γ titers in the vaccinated birds were also detected than those in the control birds. These results demonstrate that EmSAG could elicit Th1 cellular immune responses against E. maxima.

It has been noted that cell-mediated immunity is the most important immune response to Eimeria infection. In this study, the CD4+ and CD8+ percentages were higher in the groups immunised with pVAX1-EmSAG and rEmSAG protein, when compared to the control groups. This demonstrated that EmSAG might be able to stimulate cellular immunity.

IL-4 is known as a marker of the Th2 immune response [40] and has been reported as an important factor in protective immunity against parasite infections [41]. Tian et al. [42] reported that groups vaccinated with EmGAPDH exhibited higher concentrations of IL-4 compared to control groups injected with PBS and pVAX1 alone. The results of this study demonstrated an increased IL-4 level in the EmSAG-vaccinated birds compared to those in the negative control. Coupled with the high antibody concentration, these data indicate that EmSAG could stimulate humoral immune response to E. maxima.

A new class of T-helper cells known as Th17 cells is associated with interleukin IL-17 production [43]. In the avian immune system, IL-17 functions as a stimulator of cytokine productions [44]. It has been confirmed that co-vaccination of IL-17 with 3-1 E protein induced better protection against E. acervulina than 3-1 E alone [4]. Previously, it was reported that the immunisation of animals with DNA vaccines produced higher levels of IL-17 production [45]. However, IL-17 neutralised antibody treated birds showed enhanced IL-12 and IFN-γ expression [46]. In this research, a significant increment of IL-17 concentrations was detected ten days after the last immunisation. This finding coupled with the high IFN-γ titers, indicated that EmSAG could induce Th1 and Th17 response. However, the exact function of TH17 in immunisation against Eimeria spp. needs further investigation.

TGF-β is a cytokine that has been recognised as part of the immune suppression mechanism [47, 48]. TGF-β has been reported to induce protective immunity and increased TNF-α production [49, 50]. Hoan et al. [51] also reported that EbAMA1 could induce significantly higher concentrations of TGF-β1 and IL17 in the vaccinated groups. Likewise, in the current research, birds vaccinated with the rEmSAG protein and pVAX1-EmSAG showed higher concentrations of TGF-β1 than that of control groups. However, the exact function of TGF-β in protecting against coccidiosis needs further investigation.

Antibodies and cytokines have been shown to influence the protective immunity against coccidiosis infections. In previous reports, monoclonal antibodies showed the ability to reduce oocyst shedding and provide partial protection against E. maxima or E. tenella challenge infections [52, 53]. IL-4 could enhance the production of the antibody [54]. Chickens injected with recombinant IFN-γ showed improved protective immunity following E. acervulina infection [55,56,57]. Rose et al. [58] found that neutralising IFN-γ though monoclonal antibody could increase the output of oocysts and loss of body weight. Additionally, oocyst shedding was decreased in birds co-injected with IFN-γ or TGF-β with the 3-1E DNA vaccine compared to the birds inoculated with the DNA vaccine alone [59]. Lillehoj et al. [60] reported that co-vaccination with EtMIC2 and TGF-β significantly reduced oocyst shedding and enhanced weight gains beyond those injected by EtMIC2 alone. Zhang et al. [46] found that the IL-17 neutralised birds showed decreased fecal oocyst output and caecal lesion scores, as well as increased body weight gain. Geriletu et al. [44] reported that vaccination with IL-17A and MZP5-7 reduced oocyst shedding and decreased intestinal lesions following E. tenella challenge compared to inoculation with MZP5-7 alone. In this study, challenge experiments showed that the concentration of anti-EmSAG antibodies, IFN-γ, IL-4, TGF-β and IL-17 were increased in both the rEmSAG protein and pVAX1-SAG immunised groups. Additionally, the jejunal lesions, loss of body weight and oocyst production ratio were all decreased. These results indicate that the antibodies and cytokines played a role in the immune protection induced by the rEmSAG protein.

Localisation of the proteins is critical to understanding the role which they play in parasite binding and the invasion of the host cell [61, 62]. Previous studies reported that monoclonal antibodies were able to detect proteins on the parasite surface, such as EtSAG1 and the micronemes of the sporozoites and merozoites [63,64,65]. Jenkins et al. [66] showed the immune-mapped protein 1 could be detected in the sporozoites. Zhang et al. [31] found EaMIC3 on the apical tip of E. acervulina sporozoites. Our findings suggest that EmSAG is expressed in the sporozoite and merozoite stages of E. maxima, and might play an important role in the host invasion mechanism.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our findings indicate that vaccination with EmSAG is capable of eliciting both humoral immunity and cell-mediated immunity, exploring a moderate protective immunity against E. maxima. This work suggests that EmSAG could be used as an effective vaccine candidate to resist E. maxima infection.

Abbreviations

- ACI:

-

Anti-coccidial index

- Cy3:

-

Cyanine dyes 3

- DAPI:

-

2-(4-amidinophenyl)-6-indolecarbamidine dihydrochloride

- EmSAG:

-

surface antigen gene of Eimeria maxima

- IFN-γ:

-

Interferon-γ

- IgG-HRP:

-

horseradish peroxidase labeled immunoglobulin G

- IL-17:

-

Interleukin-17

- IL-4:

-

Interleukin-4

- IPTG:

-

Isopropyl-B-D-thiogalactopyranoside

- RT-PCR:

-

Reverse transcription-polymerase polymerase chain reaction

- SDS-PAGE:

-

Sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- TGF-β1:

-

Transforming growth factor-β1

- Th1:

-

helper T cell 1

- Th2:

-

helper T cell 2

References

Shirley MW, Ivens A, Gruber A, Madeira AMBN, Wan K-L, Dear PH, et al. The Eimeria genome projects: a sequence of events. Trends Parasitol. 2004;20:199–201.

Wallach M, Smith NC, Braun R, Eckert J. Potential control of chicken coccidiosis by maternal immunization. Parasitol Today. 1995;11:262–5.

Wallach MG, Ashash U, Michael A, Smith NC. Field application of a subunit vaccine against an enteric protozoan disease. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3948.

Ding X, Lillehoj HS, Quiroz MA, Bevensee E, Lillehoj EP. Protective immunity against Eimeria acervulina following in ovo immunization with a recombinant subunit vaccine and cytokine genes. Infect Immun. 2004;72:6939–44.

Shah MAA, Yan R, Xu L, Song X, Li X. A recombinant DNA vaccine encoding Eimeria acervulina cSZ-2 induces immunity against experimental E. tenella infection. Vet Parasitol. 2010;169:185–9.

Blake DP, Tomley FM. Securing poultry production from the ever-present Eimeria challenge. Trends Parasitol. 2014;30:12–9.

Widera G, Austin M, Rabussay D, Goldbeck C, Barnett SW, Chen M, et al. Increased DNA vaccine delivery and immunogenicity by electroporation in vivo. J Immunol. 2000;164:4635–40.

Song X, Zhang Z, Liu C, Xu L, Yan R, Li X. Evaluation of the persistence, integration, histopathology and environmental release of DNA vaccine encoding Eimeria tenella TA4 and chicken IL-2. Vet Parasitol. 2016;229:22–30.

Chapman H. Milestones in avian coccidiosis research: a review. Poultry Sci. 2014;93:501–11.

Dowd KA, Ko SY, Morabito KM, Yang ES, Pelc RS, Demaso CR, et al. Rapid development of a DNA vaccine for Zika virus. Science. 2016;354:237.

Gilson PR, Nebl T, Vukcevic D, Moritz RL, Sargeant T, Speed TP, et al. Identification and stoichiometry of glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored membrane proteins of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5:1286–99.

Chow Y-P, Wan K-L, Blake DP, Tomley F, Nathan S. Immunogenic Eimeria tenella glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored surface antigens (SAGs) induce inflammatory responses in avian macrophages. PLoS One. 2011;6:e25233.

Palmieri N, Shrestha A, Ruttkowski B, Beck T, Vogl C, Tomley F, et al. The genome of the protozoan parasite Cystoisospora suis and a reverse vaccinology approach to identify vaccine candidates. Int J Parasitol. 2017;47:189–202.

Tabarés E, Ferguson D, Clark J, Soon P-E, Wan K-L, Tomley F. Eimeria tenella sporozoites and merozoites differentially express glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored variant surface proteins. Mol Biochem Parasit. 2004;135:123–32.

Belli SI, Lee M, Thebo P, Wallach MG, Schwartsburd B, Smith NC. Biochemical characterisation of the 56 and 82 kDa immunodominant gametocyte antigens from Eimeria maxima. Int J Parasitol. 2002;32:805.

Wallach M, Smith NC, Petracca M, Miller CM, Eckert J, Braun R. Eimeria maxima gametocyte antigens: potential use in a subunit maternal vaccine against coccidiosis in chickens. Vaccine. 1995;13:347–54.

Liu D, Li J, Cao L, Wang S, Han H, Wu Y, et al. Analysis of differentially expressed genes in two immunologically distinct strains of Eimeria maxima using suppression subtractive hybridization and dot-blot hybridization. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:259.

Song X, Ren Z, Yan R, Xu L, Li X. Induction of protective immunity against Eimeria tenella, Eimeria necatrix, Eimeria maxima and Eimeria acervulina infections using multivalent epitope DNA vaccines. Vaccine. 2015;33:2764–70.

Smith NC, Wallach M, Miller CM, Braun R, Eckert J. Maternal transmission of immunity to Eimeria maxima: western blot analysis of protective antibodies induced by infection. Infect Immun. 1994;62:4811–7.

Huang J, Zhang Z, Li M, Song X, Yan R, Xu L, et al. Immune protection of microneme 7 (EmMIC7) against Eimeria maxima challenge in chickens. Avian Pathol. 2015;44:392–400.

Hassan IA, Wang S, Xu L, Yan R, Song X, Li X. DNA vaccination with a gene encoding Toxoplasma gondii Deoxyribose Phosphate Aldolase (TgDPA) induces partial protective immunity against lethal challenge in mice. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:431.

Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–54.

Yan R, Sun W, Song X, Xu L, Li X. Vaccination of goats with DNA vaccine encoding Dim-1 induced partial protection against Haemonchus contortus: a preliminary experimental study. RES Vet Sci. 2013;95:189–99.

Song H, Yan R, Xu L, Song X, Shah MAA, Zhu H, et al. Efficacy of DNA vaccines carrying Eimeria acervulina lactate dehydrogenase antigen gene against coccidiosis. Exp Parasitol. 2010;126:224–31.

Zhu H, Yan R, Wang S, Song X, Xu L, Li X. Identification and molecular characterization of a novel antigen of Eimeria acervulina. Mol Biochem Parasit. 2012;186:21–8.

Lillehoj HS, Jenkins MC, Bacon LD. Effects of major histocompatibility genes and antigen delivery on induction of protective mucosal immunity to E. acervulina following immunization with a recombinant merozoite antigen. Immunology. 1990;71:127–32.

Johnson J, Reid WM. Anticoccidial drugs: lesion scoring techniques in battery and floor-pen experiments with chickens. Exp Parasitol. 1970;28:30–6.

Lillehoj HS, Ding X, Quiroz MA, Bevensee E, Lillehoj EP. Resistance to intestinal coccidiosis following DNA immunization with the cloned 3-1E Eimeria gene plus IL-2, IL-15, and IFN-γ. Avian Dis. 2005;49:112–7.

Huang J, Zhang Z, Li M, Song X, Yan R, Xu L, et al. Eimeria maxima microneme protein 2 delivered as DNA vaccine and recombinant protein induces immunity against experimental homogenous challenge. Parasitol Int. 2015;64:408.

Sasai K, Aita M, Lillehoj H, Miyamoto T, Fukata T, Baba E. Dynamics of lymphocyte subpopulation changes in the cecal tonsils of chickens infected with Salmonella enteritidis. Vet Microbiol. 2000;74:345–51.

Zhang Z, Liu X, Yang X, Liu L, Wang S, Lu M, et al. The molecular characterization and immunity identification of microneme 3 of Eimeria acervulina. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 2016;63:709–21.

Jang SI, Lillehoj HS, Lee SH, Lee KW, Park MS, Cha SR, et al. Eimeria maxima recombinant Gam82 gametocyte antigen vaccine protects against coccidiosis and augments humoral and cell-mediated immunity. Vaccine. 2010;28:2980–5.

Xu Q, Song X, Xu L, Yan R, Shah MAA, Li X. Vaccination of chickens with a chimeric DNA vaccine encoding Eimeria tenella TA4 and chicken IL-2 induces protective immunity against coccidiosis. Vet Parasitol. 2008;156:319–23.

Song KD, Lillehoj HS, Choi KD, Yun CH, Parcells MS, Huynh JT, et al. A DNA vaccine encoding a conserved Eimeria protein induces protective immunity against live Eimeria acervulina challenge. Vaccine. 2000;19:243–52.

Constantinoiu CC, Molloy JB, Jorgensen WK, Coleman GT. Antibody response against endogenous stages of an attenuated strain of Eimeria tenella. Vet Parasitol. 2008;154:193–204.

Wallach M. Role of antibody in immunity and control of chicken coccidiosis. Trends Parasitol. 2010;26:382–7.

Lin R-Q, Lillehoj HS, Lee SK, Oh S, Panebra A, Lillehoj EP. Vaccination with Eimeria tenella elongation factor-1α recombinant protein induces protective immunity against E. tenella and E. maxima infections. Vet Parasitol. 2017;243:79–84.

Kaspers B, Lillehoj HS, Jenkins MC, Pharr GT. Chicken interferon-mediated induction of major histocompatibility complex Class II antigens on peripheral blood monocytes. Vet Immunol Immunop. 1994;44:71–84.

Lillehoj HS, Choi KD. Recombinant chicken interferon-gamma-mediated inhibition of Eimeria tenella development in vitro and reduction of oocyst production and body weight loss following Eimeria acervulina challenge infection. Trends Parasitol. 1998;42:307–14.

Inagaki-Ohara K, Dewi FN, Hisaeda H, Smith AL, Jimi F, Miyahira M, et al. Intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes sustain the epithelial barrier function against Eimeria vermiformis infection. Infect Immun. 2006;74:5292–301.

Fallon PG, Jolin HE, Smith P, Emson CL, Townsend MJ, Fallon R, et al. IL-4 induces characteristic Th2 responses even in the combined absence of IL-5, IL-9, and IL-13. Immunity. 2002;17:7–17.

Tian L, Li WY, Huang XM, Tian D, Liu JH, Yang XC, et al. Protective efficacy of coccidial common antigen glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) against challenge with three Eimeria species. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:1245.

Chen Z, O’Shea JJ. Th17 cells: a new fate for differentiating helper T cells. Immunol Res. 2008;41:87–102.

Geriletu XL, Xurihua LX. Vaccination of chickens with DNA vaccine expressing Eimeria tenella MZ5-7 against coccidiosis. Vet Parasitol. 2011;177:6–12.

Hoan TD, Zhang Z, Huang J, Yan R, Song X, Xu L, et al. Identification and immunogenicity of microneme protein 2 (EbMIC2) of Eimeria brunetti. Exp Parasitol. 2016;162:7–17

Zhang L, Liu R, Song M, Hu Y, Pan B, Cai J, et al. Eimeria tenella: Interleukin 17 contributes to host immunopathology in the gut during experimental infection. Exp Parasitol. 2013;133:121–30.

Kehrl JH, Roberts A, Wakefield L, Sp J, Sporn M, Fauci A. Transforming growth factor beta is an important immunomodulatory protein for human B lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1986;137:3855–60.

Kehrl JH, Wakefield LM, Roberts AB, Jakowlew S, Alvarez-Mon M, Derynck R, et al. Production of transforming growth factor beta by human T lymphocytes and its potential role in the regulation of T cell growth. J Exp Med. 1986;163:1037–50.

Song H, Song X, Xu L, Yan R, Shah MAA, Li X. Changes of cytokines and IgG antibody in chickens vaccinated with DNA vaccines encoding Eimeria acervulina lactate dehydrogenase. Vet Parasitol. 2010;173:219–27.

Gray JD, Liu T, Huynh N, Horwitz DA. Transforming growth factor beta enhances the expression of CD154 (CD40L) and production of tumor necrosis factor alpha by human T lymphocytes. Immunol Lett. 2001;78:83–8.

Hoan TD, Thao DT, Gadahi JA, Song X, Xu L, Yan R, et al. Analysis of humoral immune response and cytokines in chickens vaccinated with Eimeria brunetti apical membrane antigen-1 (EbAMA1) DNA vaccine. Exp Parasitol. 2014;144:65–72.

Wallach M, Pillemer G, Yarus S, Halabi A, Pugatsch T, Mencher D. Passive immunization of chickens against Eimeria maxima infection with a monoclonal antibody developed against a gametocyte antigen. Infect Immun. 1990;58:557–62.

Karim MJ, Basak SC, Trees AJ. Characterization and immunoprotective properties of a monoclonal antibody against the major oocyst wall protein of Eimeria tenella. Infect Immun. 1996;64:1227–32.

Snapper CM, Finkelman FD, Stefany D, Conrad DH, Paul WE. IL-4 induces co-expression of intrinsic membrane IgG1 and IgE by murine B cells stimulated with lipopolysaccharide. J Immunol. 1988;141:489–98.

Lillehoj HS, Ruff MD. Comparison of disease susceptibility and subclass-specific antibody response in SC and FP chickens experimentally inoculated with Eimeria tenella, E. acervulina, or E. maxima. Avian Dis. 1987;31:112–9.

Lillehoj HS, Choi KD. Recombinant chicken interferon-gamma-mediated inhibition of Eimeria tenella development in vitro and reduction of oocyst production and body weight loss following Eimeria acervulina challenge infection. Avian Dis. 1998;42:307–14.

Lowenthal JW, York JJ, O'Neil TE, Rhodes S, Prowse SJ, Strom DG, et al. In vivo effects of chicken interferon-gamma during infection with Eimeria. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 1997;17:551–8.

Rose ME, Wakelin D, Hesketh P. Interferon-gamma-mediated effects upon immunity to coccidial infections in the mouse. Parasite Immunol. 1991;13:63–74.

Min W, Lillehoj HS, Burnside J, Weining KC, Staeheli P, Zhu JJ. Adjuvant effects of IL-1beta, IL-2, IL-8, IL-15, IFN-alpha, IFN-gamma TGF-beta4 and lymphotactin on DNA vaccination against Eimeria acervulina. Vaccine. 2001;20:267–74.

Lillehoj HS, Ding X, Dalloul RA, Sato T, Yasuda A, Lillehoj EP. Embryo vaccination against Eimeria tenella and E. acervulina infections using recombinant proteins and cytokine adjuvants. J Parasitol. 2005;91:666–73.

Liu T, Huang J, Ehsan M, Wang S, Fei H, Zhou Z, et al. Protective immunity against Eimeria maxima induced by vaccines of Em14-3-3 antigen. Vet Parasitol. 2018;253:79–86.

Danforth HD. Use of monoclonal antibodies directed against Eimeria tenella sporozoites to determine stage specificity and in vitro effect on parasite penetration and development. Am J Vet Res. 1983;44:1722–7.

Trees AJ, Karim MJ, McKellar SB, Carter SD. Eimeria tenella: local antibodies and interactions with the sporozoite surface. J Protozool. 1989;36:326–33.

Jahn D, Matros A, Bakulina AY, Tiedemann J, Schubert U, Giersberg M, et al. Model structure of the immunodominant surface antigen of Eimeria tenella identified as a target for sporozoite-neutralizing monoclonal antibody. Parasitol Res. 2009;105:655–68.

Sasai K, Fetterer RH, Lillehoj H, Matusra S, Constantinoiu CC, Matsubayashi M, et al. Characterization of monoclonal antibodies that recognize the Eimeria tenella microneme protein MIC2. J Parasitol. 2008;94:1432–4.

Jenkins MC, Fetterer R, Miska K, Tuo W, Kwok O, Dubey JP. Characterization of the Eimeria maxima sporozoite surface protein IMP1. Vet Parasitol. 2015;211:146.

Acknowledgments

We greatly acknowledge the contribution of Dr Ibrahim Hassan from Shanghai Veterinary Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences for valuable suggestions and necessary amendments in this manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Joint Research Project of the National Natural Science Foundation of China and the Pakistan Science Foundation (NSFC-PSF) (Grant No. 31661143017), the National Natural Science Foundation of PR China (Grant No. 31372428), and the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this article. The sequence was submitted to the GenBank database under the accession number XM_013482011.1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LXR directed the project and participated in all management co-ordination regarding this study. LTQ wrote the manuscript and performed experiments. HJW, LYL, WS and ZZY helped to perform laboratory tests and analysed data. ME helped to rectify grammatical mistakes in manuscript. All analytical tools and reagents were provided by SXK, YRF and XLX. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

This study was conducted in accordance with the recommendations of the guidelines of the Animal Ethics Committee, Nanjing Agricultural University, China. The protocol was approved by the Science and Technology Agency of Jiangsu Province (approval ID, SYXK (SU) 2010–0005).

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, T., Huang, J., Li, Y. et al. Molecular characterisation and the protective immunity evaluation of Eimeria maxima surface antigen gene. Parasites Vectors 11, 325 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-018-2906-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-018-2906-5