Abstract

Background

Audit and feedback is effective in improving the quality of care. However, methods and results of international studies are heterogeneous, and studies have been criticized for a lack of systematic use of theory. In TREC (Translating Research in Elder Care), a longitudinal health services research program, we collect comprehensive data from care providers and residents in Canadian nursing homes to improve quality of care and life of residents, and quality of worklife of caregivers. The study aims are to a) systematically feed back TREC research data to nursing home care units, and b) compare the effectiveness of three different theory-based feedback strategies in improving performance within care units.

Methods

INFORM (Improving Nursing Home Care through Feedback On PerfoRMance Data) is a 3.5-year pragmatic, three-arm, parallel, cluster-randomized trial. We will randomize 67 Western Canadian nursing homes with 203 care units to the three study arms, a standard feedback strategy and two assisted and goal-directed feedback strategies. Interventions will target care unit managerial teams. They are based on theory and evidence related to audit and feedback, goal setting, complex adaptive systems, and empirical work on feeding back research results. The primary outcome is the increased number of formal interactions (e.g., resident rounds or family conferences) involving care aides – non-registered caregivers providing up to 80% of direct care. Secondary outcomes are a) other modifiable features of care unit context (improved feedback, social capital, slack time) b) care aides’ quality of worklife (improved psychological empowerment, job satisfaction), c) more use of best practices, and d) resident outcomes based on the Resident Assessment Instrument – Minimum Data Set 2.0. Outcomes will be assessed at baseline, immediately after the 12-month intervention period, and 18 months post intervention.

Discussion

INFORM is the first study to systematically assess the effectiveness of different strategies to feed back research data to nursing home care units in order to improve their performance. Results of this study will enable development of a practical, sustainable, effective, and cost-effective feedback strategy for routine use by managers, policy makers and researchers. The results may also be generalizable to care settings other than nursing homes.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02695836. Date of registration: 24 February 2016

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Importance of residential long term care

In Western countries, 3-8% of people aged 65 years or older live in nursing homes [1, 2] (e.g., 224 thousand in Canada [3], 1.3 million in the USA [4], and 2.9 million in Europe [1]), and demand for these services will substantially increase [1, 5, 6]. Between half and three quarters of nursing home residents have dementia (with a rising trend) [7–10], and these figures are likely underrated by at least 11% [11]. Dementia progresses from mild impairment and difficulties organizing daily life to incontinence, unsteadiness, profound difficulties in communication and nutrition intake, confinement to bed, and finally death [8, 12, 13]. In 2015, 46.8 million people aged 60 years or older were living with dementia worldwide (4.8 million in North America, and 7.5 million in Western Europe) [14], and 96% of US Americans with Alzheimer’s (the most common type of dementia) are 65 years or older [12]. Global numbers of older people with dementia will increase to 131.5 million by 2050. Currently, dementia has no prevention, cure, or effective treatment [12]. Without dramatic breakthroughs in either prevention or treatment, as the number of frail elderly increases, so will their eventual need for nursing home care.

As older adults with dementia are able to remain at home longer with community care, future trends will be for transition to a nursing home later in the dementia trajectory [5, 15]. This will further increase levels and complexity of care in these settings. At the same time, absolute staffing levels and proportions of regulated staff are low in nursing homes, and up to 80% of direct care is provided by unregulated care providers (care aides) with little or almost no formal training [16–19].

Ongoing challenges to quality of care and use of best practices

Quality of care in nursing homes has been a challenge for decades [20–23] and evidence to support consistent quality improvement strategies is still lacking [21, 24]. Multiple international reports [23, 25–29] describe sub-optimal quality of care in nursing homes. For example, rates of adverse events (e.g., pressure ulcers) vary up to 10-fold across facilities [30], are much higher at particular times during a nursing home stay [30–34], and vary across nursing home ownership models [30, 35].

In acute and primary care, we know that persistent and deeply troubling research–practice gaps exist across countries, professions, and settings [36–39]. A reported 30–40% of patients do not receive evidence-based care and 25% receive unnecessary or potentially harmful care [40, 41]. In the nursing home sector these performance gaps result in deleterious resident outcomes (e.g., high modifiable symptom burden in the last year of life, unnecessary and inappropriate transfer to hospital especially in the last weeks of life) and deleterious workforce outcomes (e.g., high burnout, reduced job satisfaction). Almost no knowledge translation (KT) research has been undertaken in the nursing home sector [36, 42, 43] and only recently have there been calls for such research [44–46]. There is little work developing effective and efficient means by which to tailor and deliver ongoing performance data to foster intentional action to improve quality of care and worklife. There has been even less work rigorously evaluating such strategies. We located no work attempting to tailor organizational context data into performance data. Under these conditions, leaders in the nursing home sector are faced with daunting challenges in delivering acceptable standards of care. They have little guidance on how to feasibly identify actionable performance gaps over time or how to respond to them.

The Translating Research in Elder Care (TREC) research program

This project is a key element of our long term program of research (Translating Research in Elder Care – TREC) focused on advancing KT science [47, 48]. TREC’s mission is to improve quality of care and quality of life for older adults in nursing homes and work life for their care providers. At its most fundamental level, the goal of KT in clinical settings is to move research (e.g., performance data) to action (e.g., performance improvement). TREC is an ongoing research program and aims to create actionable performance data to improve performance at the clinical microsystem (care unit) level in nursing homes. The microsystem has rarely been targeted before in performance improvement trials and possesses unique features that make it key to leading care interventions and driving change in these settings [49, 50]. Our previous research demonstrated that members of the clinical microsystem are the best potential target to drive positive change in this field [49, 50]. Findings from this investigation will add new insights on how actionable research data on modifiable elements of organizational context (framed as performance data) can be used to improve performance in a complex adaptive system such as a nursing home [51]. The next two sections describe the relevance of clinical microsystems and the microsystem work context for performance improvement.

Relevance of clinical microsystems

Focusing on clinical microsystems as the target for improvement activities is central to our work [52–54]. These “small group[s] of people who work together on a regular basis to provide care to discrete subpopulations of patients” (p. 474) are essential building blocks of organizations and the health system [55], and a critical target level for patient safety interventions [56]. Care services are often organized at this microsystem level [57] and individual residents receive care on care units embedded in organizations [58]. Targeting improvement strategies to the microsystem level can potentially transform health care systems [55]. Emerging international evidence suggests that improvement efforts focusing on the microsystem level are successful [54, 59, 60]. We found that the microsystem level explained a significantly higher percentage of variance in work context outcomes (e.g., leadership, culture, evaluation) than did individual (resident/caregiver) or facility levels [49]. Using longitudinal data on three risk-adjusted quality indicators (QIs) from the Resident Assessment Instrument – Minimum Data Set (RAI-MDS) 2.0 [61], we found that facility level reporting masks important inter-unit/intra-facility variation; thus quality improvement interventions should target both facility and microsystem levels [50]. The intervention described here targets the leaders of these clinical microsystems. Using a complex adaptive system lens in the nursing home sector, Anderson [62, 63] suggested fostering manager development as the key to effective performance improvement. Similarly, McDaniel et al. [64–66] argue that health care organizations are complex adaptive systems.

Relevance of the care unit work context

Studies in nursing homes have increasingly focused on the broad contextual influences of organizations. Generally, context is theorized as culture [67–71], where specific elements (e.g., person-centeredness, staff engagement) are identified, measured, and associated with outcomes of interest (e.g., quality of life or care). Reports associate more positive cultures (more person-centered, less controlling, more relationship-based) with lower rates of feeding tube placement [69], lower restraint use [72], reduction in anti-psychotic prescribing [73], and better quality of care [74]. The influence of context on successful adoption of innovation and on quality improvement success was suggested theoretically [75–85], examined empirically [57, 86–91], and has been the subject of several reviews [92–97]. The consensus is that context is an important influence on implementation success. Dopson and Fitzgerald [98] for example, synthesized 39 case studies probing context and found it an important mediator of innovation. They identified several contextual processes important to innovation adoption and, we argue, to using performance data to achieve performance goals. Among these processes were (1) sensing, interpreting, and integrating new evidence; (2) reinforcing or marginalizing new evidence; (3) relating new evidence to local context needs; and (4) discussing/debating new evidence with local stakeholders. Recent systematic reviews [96, 97, 99, 100] identified organizational features such as complexity, centralization, size, a research champion, organizational slack, and resources as important to innovation success. Positive influences include cultural context (culture, climate, openness to change, organizational innovativeness, leadership, evaluation, feedback), structural context (organizational structure, management and supervision, resources, time, staff development), physical context (organizational size), and social context (social influence, collaboration, relational capital, communication, participation in decision making). We have repeatedly demonstrated that organizational context as measured using the Alberta Context Tool (ACT) [77, 80, 101–105] has a positive association with better scores on staff outcomes (best practice use, burnout, job satisfaction) [57, 87, 88, 102, 103, 105] and recently have demonstrated this effect on resident outcomes [106].

Purpose and aims

We seek to improve quality of care and performance/outcomes by translating findings on modifiable elements of organizational context (work environment). The purpose of this project is to systematically evaluate tailored interventions targeting the leaders of clinical microsystems in nursing homes. The interventions are designed to feed back performance data for improvement. Our aims are:

-

1.

To evaluate and compare three feedback strategies – a standard feedback strategy and two assisted and goal-directed feedback strategies

-

2.

To assess possible longer term effects of each strategy

-

3.

To refine, based on the outcomes of this evaluation, a practical assisted feedback strategy for use in the nursing home sector that targets the leaders of their clinical microsystems

Methods/Design

Design

This is a protocol for a pragmatic, three-arm, parallel, cluster-randomized trial using stratified permuted block randomization with baseline assessment, a one-year intervention period, post-intervention assessment, and 18-months long-term follow-up (Table 1). This protocol followed the SPIRIT reporting guidelines for trial protocols [107] (Additional file 1). Should we need to make important modifications to this protocol, we will revise our study registration and ethics application (including all relevant study documents) accordingly, inform all relevant stakeholders (investigators, trial participants, regulators), and will report protocol changes in our final publication of study results. We have established a structure of committees and working groups to facilitate intervention development and implementation, and to ensure scientific rigor (Additional file 2). We will disseminate study results in peer-reviewed publications and international conference presentations.

INFORM is set in urban nursing homes participating in our current phase of TREC – a stratified (region by size by operator) random sample of 91 urban sites. We recruited these sites recruited from three provinces: Alberta, British Columbia, Manitoba. These TREC facilities participate in a longitudinal observational study that generates a rich set of resident, staff, unit, and facility level measures and outcomes. Data from this ongoing observational study forms the baseline assessment, and data from future waves of this study will form the post-intervention and long-term follow-up assessments. We will invite all eligible sites in Alberta and British Columbia to participate in INFORM (sample information sheet and informed consent, Additional file 3). TREC Manitoba facilities are not eligible to INFORM, as they are participating in another TREC intervention study.

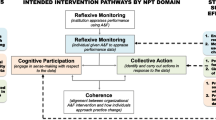

Intervention

The following theoretical foundations informed intervention development: (a) audit and feedback in the health care literature, (b) feedback in the organizational literature, (c) goal setting theory, and (d) experiences from feedback activities during the first phase of our work (Additional file 4). The intervention target is the clinical microsystem managerial team within nursing homes: unit care managers and the director of care. We will feed back data about four aspects of organizational context that we routinely measure in our program with the validated ACT [80, 104]: (1) the number of formal interactions care aides have with other providers and with patients/families; (2) the amount of slack time care aides have; (3) evaluation (unit feedback) practices, and (4) social capital. We purposefully selected these four concepts and defined formal interactions (FI) as our primary outcome for the following reasons (details Additional file 5):

-

a)

of the ten ACT concepts, FI best reflects if a care unit has a more or less favorable work context, suggesting that improving FI improves context in general;

-

b)

FI scores are generally low in our study sample (mean = 1.32, possible maximum = 4), suggesting substantial room for improvement;

-

c)

based on theory and care unit managers’ opinions, FI is highly modifiable;

-

d)

systematically involving care aides in FIs (e.g., resident rounds) can provide care aides as well as the care team with crucial information about residents.

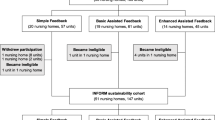

The study will include three study arms: (1) Standard Feedback (SF), (2) Basic Assisted Feedback (BAF), and (3) Enhanced Assisted Feedback (EAF) (Fig. 1).

Dissemination workshops

All TREC sites have received SF in October/November 2015, which included participation in a face-to-face Dissemination Workshop. During these half-day workshops, we presented feedback reports with a particular focus on the core set of actionable context targets (FI, evaluation, social capital, slack time). A trained facilitator ran these workshops, a senior researcher presented on the reports, and participants engaged in small group discussions to: (a) help with interpretation of results overall, (b) draw attention to elements of context that are modifiable, (c) encourage microsystem teams to improve more modifiable context elements. We did not set specific goals – we provided simple “do your best” instructions.

Goal Setting Workshops

Facilities in the BAF and EAF arm will participate in an additional face-to-face Goal Setting Workshop. In each of four regions (Edmonton, Calgary, Interior Health, Fraser Health) we will hold a separate workshop for BAF and EAF sites. We expect an average number of 10-20 participants at each workshop (i.e., approximately 0.5-1 person per care unit). Care managers (who are the primary target group of this intervention) often oversee more than one care unit in their facility at the same time. We will prepare a Goal Setting Workshop Package for each care unit, including (a) a feedback report on the care unit’s context data (FI, evaluation, social capital, slack time), and (b) a Goal Setting Workbook summarizing important details on the INFORM study, defining key concepts, and outlining the goal setting approach we are going to apply. We will send this Goal Setting Workshop Package to each participating unit one week ahead of the workshop. The workshops will take place at a conference venue (e.g., a hotel) located in the respective health region of the participating facilities. The workshops will involve small group activities that adhere to feedback and goal setting approaches including: (a) reflecting on context data, (b) performance goal setting, including establishing a series of proximal and/or learning goals that will provide teams with markers of progress and explicit strategies for attaining performance goals, respectively, and (c) identification of ways care unit managers can gather interim feedback to assess progress towards goal achievement. The same trained facilitator as in the Dissemination Workshops will lead the Goal Setting Workshops. A researcher and regional decision maker dyad will be present with expertise in performance data and the specific clinical care setting, respectively. The same researcher will attend all workshops; the regional decision maker will be specific to each respective region. Participants will generate an action plan and will receive instructions for tracking goal progress and reporting at the support workshops. Additionally, we will assist workshop participants to develop specific, measurable goals and tools to track goal achievement. For example, if a care unit managerial team defines the goal to include at least four care aides in their monthly family conferences, we will provide managers with a run chart template to track the number of care aides included in each of those meetings during the study.

Support workshops

Six months after the Goal Setting Workshop we will hold a 90-min. virtual support workshop (webinars) in the BAF arm and a 180-min. face-to-face support workshop in the EAF arm (using the same conference venues as for the Goal Setting Workshops). Groups will (a) report on their progress with proximal/learning goals and strategies used toward performance goals, (b) discuss challenges they encountered, and (c) receive support from the researcher–decision maker dyad in addressing these challenges. BAF participants will receive limited online peer-to-peer support, EAF participants will benefit from face-to-face support from peers and research team members. Six months later we will hold a second support workshop in the BAF and EAF arms, similar in content to the first. The second support workshops are designed to continue to help participants discuss progress and problem solve. To ensure consistency in intervention delivery, the same trained facilitator will lead all BAF and EAF workshops, and the same researcher–decision maker dyad as in the Goal Setting Workshops will be present. Participants will receive push emails three months before each support workshop to remind them of the dates and the tasks to prepare.

On-demand e-mail and phone support

EAF teams will also have access to on-demand e-mail and phone support from the facilitator throughout the intervention period to address questions they may have and help resolve challenges that arise as they work towards goal achievement.

Sample

Sample size calculation

The intervention target are the nursing home care units (clinical microsystems). To avoid contamination effects, we will randomize at the facility level, with all unit managers of the same facility receiving the same feedback intervention. Due to the three-arm design, multiple repeated measures, and the complex nested structure (time points nested within each care unit, and units clustered within facilities), basic methods of sample size estimation are not applicable [108–110]. Therefore, we adapted a computer simulation-based approach described by Arnold et al. [108] using the statistics software R (version 3.1.2) [111]. Power and sample size were based on the following mixed-effects regression model:

-

Yijt is the ACT Formal Interactions (FI) score (primary outcome) of unit j in facility i at time t.

-

μ is the FI population mean.

-

A1ijt, A2ijt, and A3ijt are indicator variables for the interventions (SF, BAF, and EAF, respectively). The indicator variable is 1 if the unit has been exposed to the respective intervention and 0 otherwise.

-

β1, β2, and β3 are the treatment effects of the three interventions.

-

bi is a facility-level random effect (variability of units within the facility).

-

bij is a unit-level random effect (variability of time points within the unit).

-

εijt is a residual term (variability between units).

We assumed that the random effects and the residual term were normally distributed with mean zero and uncorrelated with one another. Using data from the previous phase of TREC (2007–2012) we estimated the following parameters to be entered into the model:

-

μ = 1.1 (FI mean was 1.32. Standard feedback here is similar to that provided in the previous TREC phase [112–114]. We assumed that this intervention will, at least, have a small effect (increase the FI score by 0.2) compared to no feedback.

-

Standard deviation of bi = 0.154 (ICC = 0.445) (FI variability of units, within facilities)

-

Standard deviation of bij = 0.104 (FI variability of units, across waves 1 and 2 in TREC 1.0)

-

Standard deviation of εijt = 0.192 (variability of the unit FI residual term)

-

Average cluster size = 3 units per facility

We assumed that the FI score will increase by β1 = 0.2 in the SF group, by β2 = 0.4 in the BAF group, and by β3 = 0.6 in the EAF group. Based on these simulations (Fig. 2) 12 facilities per study arm (on average 3 units per facility) are required to detect the assumed effects with a statistical power of 0.90. To allow for attrition and effects smaller than the assumed ones, we will invite all eligible units in the 67 eligible facilities (see below) in Alberta and British Columbia for participation.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

To be eligible (Table 2), facilities and units have to participate in the TREC observational study, as INFORM outcomes are only available for these facilities. We will only include facilities and units located in Alberta or British Columbia, as the TREC Manitoba facilities are participating in another TREC intervention study. Facilities need to have at least one unit with ten or more care aide responses on the TREC survey used to assess organizational context and staff outcomes. Only care units with ten or more care aide responses on the baseline TREC survey are eligible. From our previous work [115] we know, this number is required to ensure stable, valid and reliable aggregation of the study outcomes at the unit-level. From our observational study we know, there are two facilities for which we cannot assign HCA surveys to the microsystem. We excluded them as unit-level analyses are not possible for those facilities. We will only include units with an identifiable care manager or leader accountable.

Based on these criteria, 203 units in 67 facilities are potentially eligible.

Enrolment, randomization, allocation

An independent person, not otherwise involved in this study, randomly assigned the 67 facilities to each of the three study arms. Randomization was stratified by health region (Edmonton, Calgary, Fraser Health, Interior Health) to account for the different policies within those regions that might influence organizational context and quality of care, and to facilitate delivery of the feedback intervention. We maintained regional proportionality of the 67 facilities within each study arm. From the list of facilities in each of the four regions, we selected the required number of facilities to be assigned to each of the three study arms by assigning a computer-generated random number to each facility. To facilities assigned to BAF or EAF we will offer additional feedback. We will explain to managers the specific extra feedback (treatment) they will receive, but we will blind them to group allocation.

Prevention of contamination

To limit the possibility of contamination, we will perform a cluster randomization. While we cannot prevent managers from talking to each other at regional or provincial meetings, contamination is less likely when study units are physically separate, interventions are more complex, and/or aim at changing behavior [116, 117]. We will also enlist participants’ agreement a priori to not share workshop tools with other managers or facilities during the study. The INFORM intervention is a complex intervention involving professionally facilitated face-to-face and virtual interaction with guided goal setting. It is therefore unlikely that managers in SF sites would be able to implement such an intervention unaided [118] or to change practice by virtue of interaction with intervention site managers at professional and other similar meetings. While we cannot fully blind all participants to all aspects of the study, we have undertaken comprehensive efforts to blind different stakeholder groups involved in INFORM as best as possible (details Additional file 6).

Outcomes and instruments

Additional file 7 contains a summary table listing study outcomes, tools used to assess these outcomes, and their psychometric properties. Our outcome definition includes the name of the outcome, the time point each outcome will be assessed, the method of aggregation, the metric (e.g., change from baseline or group differences at a given time), the definition of the concept assessed, psychometric properties and an example item of each scale used.

Primary outcome

Based on arguments outlined in Additional file 5, we selected the ACT FI score as the primary outcome. FI is defined as “formal exchanges that occur between individuals working within an organization (unit) through scheduled activities that can promote the transfer of knowledge” [80]. The FI scale consists of four items asking care aides how often, in the last typical month, they participated in (a) team meetings about residents, (b) family conferences, (c) change-of-shift report, and (d) continuing education (conferences, courses) outside the nursing home (rated from 1 = never to 5 = almost always). The overall score is generated by recoding each item (1 and 2 to 0; 3 to 0.5; 4 and 5 to 1) and summing recoded values (possible range: 0–4).

Secondary outcomes

Organizational

We will assess three additional organizational context factors (evaluation, social capital, slack time) using the ACT, which is embedded within the TREC care aide survey, a suite of validated survey instruments completed by computer-assisted personal interview. We will also capture response to major near misses and managers’ organizational citizenship behavior, using data from our TREC unit survey, and performance reports and quality improvement activities, using data from our TREC facility survey. These instruments are described elsewhere [48, 49, 80, 102, 119].

Staff

We will capture instrumental and conceptual best practice use, psychological empowerment, job satisfaction, and a number of individual staff attributes, using the TREC care aide survey.

Residents

We will obtain resident data from the RAI-MDS 2.0, which is used internationally for comprehensive geriatric assessment of the health, physical, mental, and functional status of nursing home residents [61]. In Canada its use is mandated in several provinces/territories, as well as by the Canadian Institute of Health Information for national reporting [120]. Data for calculating QIs are captured in quarterly assessments completed on all residents [121]. The two practice sensitive (i.e., modifiable by care staff) QIs [122] worsening pain and declining behavioural symptoms will form the focus at unit and facility levels.

Process measures

Evaluation of the intervention sessions

We will adapt previously used questionnaires to the needs of this study. These surveys will include closed and open ended questions relating to participants’ intention to change, satisfaction with intervention components and with the intervention overall. These evaluation forms will be completed by participants at the end of the Goal Setting Workshops for both the BAF and the EAF arms, and at the end of the two support workshops; virtual for the BAF arm and face-to-face for the EAF arm.

Evaluation of intervention fidelity

To ensure that each intervention session is delivered as planned, consistently across arms and time, staff will work from study protocols. To evaluate protocol fidelity, study staff will observe, using a protocol checklist, adherence to workshop protocols during actual workshop delivery. There will also be space for staff to record field notes during each intervention session. We will track (a) how many of the participants invited to the workshops attended the workshops, (b) how many of the participants attended the workshop the full time, and (c) how many of the participants completed the workshop evaluations. For consistency of workshop delivery, the same facilitator and researcher will be present in all workshops. The regional lead will change for each region, but will be consistent across workshops within one region. For consistency of evaluation, the same staff member will complete field notes and fidelity checklist across workshops. This person will also run workshop debriefing sessions with the facilitator and researcher-regional decision maker dyad.

Evaluation of processes in the facilities

We will evaluate with the BAF and EAF managerial care teams: (1) to what extent they achieved the quality improvement goals defined in the workshops, (2) if they were able to apply the planned strategies in practice, (3) barriers and facilitators encountered, and (4) strategies applied to overcome challenges. We will conduct the evaluations as follows:

-

1.

Detailed documentation of the first support workshop: We will document discussions and results in the first support workshop around the above named topics using detailed field notes, and we will analyze them using qualitative content analysis.

-

2.

Focus Group 1: We will hold the first focus group one month following the second support workshop for BAF and EAF arms. The second support workshop is the final intervention component to which the participants are exposed. This will provide participants with the opportunity to reflect on the entire INFORM Intervention. We will ask participants in each region to sign up for a teleconference focus group session held at varying times to meet the needs of individual schedules (held separately for BAF and EAF groups).

-

3.

Focus Group 2: We will hold the second focus group (organized the same way as the first focus group) one month before the long-term follow up data collection for both intervention arms. This will enable the research team to assess sustainability of the INFORM Interventions.

We will also conduct semi-structured interviews with SF care unit managers. We will ask questions about: people’s understanding of the ACT data, changes made on their unit as a result of feedback they received during the Fall 2015 TREC dissemination meetings, and barriers/facilitators to change. These interviews will allow us to compare the three study arms in terms of their ability to use the ACT data to improve context – the ultimate aim of INFORM. SF interviews will also provide information on additional quality improvement activities outside of INFORM, which may have contributed to unexpected “context” improvement during the intervention period.

Cost assessment

We will assess costs for delivering the INFORM interventions. We will not include costs related to developing the interventions and to assessing the effectiveness of the interventions (i.e., research costs). Using these data, we will assess and compare intervention delivery costs for the three study arms. We will collect data on all direct salary (workshop facilitator) and non-salary operating and travel expenses from University of Alberta accounting software, itemized by subcategory. The facilitator and study staff will keep detailed records of time invested in preparing and delivering each intervention. The cost of time invested by regional investigators and decision makers will be included. We will ask care unit managers monthly how much additional time and costs they and their staff spent on INFORM activities (i.e., not related to regular care or quality improvement activities), using standardized questions.

Statistical analysis

Primary analysis

To compare the effectiveness of the three feedback strategies in improving the FI score, we will use mixed-effects regression models: multiple, linear, multi-level regression models including random and fixed (or mixed) effects.

Controlling for potential biases

We will account for multiple measures within each unit and clustering of units within facilities. We will adjust all analyses for the three stratification variables of the TREC facility sample (region, owner-operator model and facility size). We will compare characteristics of units and facilities using descriptive statistics at baseline, and adjust where there are significant differences between treatment groups (as baseline difference can occur by chance despite appropriate randomization). Should data not meet the assumptions of this model (multivariate normality, linearity, normally distributed, uncorrelated residuals, random effects with mean zero) the model will be adjusted accordingly. Within TREC, there is an extensive program to monitor and assure data quality, and a comprehensive data cleaning processes [123]. We will carry out an intention-to-treat analysis, as this best reflects the pragmatic nature of the study. We will compare these results to a per-protocol analysis, which better reflects adherence/non-adherence with the intervention. We will consider a care unit to be adherent with the intervention if at least one representative of this unit attends the Goal Setting Workshop and at least one of the two Support Workshops. The person attending the Goal Setting Workshop can be different from the person attending the Support Workshop(s). Units only attending the Goal Setting Workshop or not attending any of the workshops will be defined as non-adherent. We have registered the trial with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02695836) and we will use CONSORT guidelines [124] to report its findings.

Secondary analyses

We will monitor change of secondary outcomes over time in each study arm, and compare outcomes between three study arms using descriptive statistics, statistical process control methods and appropriate significance tests (t tests for normally distributed, linear, continuous outcomes; non-parametric tests for variables that do not meet these assumptions; chi-squared tests for categorical outcomes). We will longitudinally track two practice sensitive RAI QIs (worsening pain, declining behavioural symptoms), using statistical process control methods [125–128]. We will calculate risk-adjusted and unadjusted indicators and, using control charts, graphically display unit and facility performances. These data will enable us to assess possible effects of INFORM on resident care as measured by resident QIs at a time consistent with the intervention. We will assign a dichotomous variable (improved/not improved) to each unit in the intervention. Then, using logistic regression with improvement as the outcome we will investigate the effects of context (using ACT scales), best practice use, and staff characteristics on improvement. To this end we have developed a reliable classification system for individual control charts [49, 50].

Discussion

INFORM is the first study to systematically assess effectiveness of different strategies to feed back research-based performance data to nursing home care units in order to improve their performance. In TREC we collect comprehensive longitudinal data on nursing home and care unit structural characteristics; modifiable features of nursing home and care unit work contexts; care providers’ use of best practices, health and quality of worklife; and various resident outcomes based on the RAI-MDS 2.0. Systematic feedback of these research data has been an important part of the long term TREC program. With INFORM we will be able to not only feed back data, but to systematically and comprehensively assess the most effective and cost-effective way to do so.

Our feedback interventions are based systematically on theory and evidence related to audit and feedback in the health care and organizational literature, goal setting, complex adaptive systems, and our own experiences with feeding back research results. This addresses Ivers and colleagues’ urgent call for systematic use of theory in future audit and feedback studies [129–131]. Furthermore, in order to determine which approaches to audit and feedback are most likely to change behaviours and improve performance, and to understand why these approaches work, head-to-head comparisons of different audit and feedback approaches, rather than comparison of audit and feedback with no intervention, are needed [129, 130].

We hypothesize that BAF and EAF will be significantly more effective than SF in improving formal interactions, context overall, and care provider as well as resident outcomes on nursing home care units. We furthermore expect that BAF and EAF will be similarly effective in doing so. However, we expect BAF to be more cost-effective than EAF. Results of this study will enable us to develop a practical, sustainable, effective, and cost-effective assisted feedback strategy that managers and policy makers can routinely use to improve performance of nursing home care units.

Trial status

We have started recruitments of facilities and managerial teams on March 01, 2016, and recruitment is ongoing.

References

European Commission. Long-term care for the elderly: provisions and providers in 33 European countries. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union; 2012.

Hix C, McKeon L, Walters S. Clinical nurse leader impact on clinical microsystems outcomes. J Nurs Adm. 2009;39:71–6.

Statistics Canada. Living arrangements of seniors: Families, households and marital status. Structural type of dwelling and collectives, 2011 Census of Population. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2011.

Harrington C, Carrillo H, Garfield R. Nursing facilities, staffing, residents and facility deficiencies, 2009 Through 2014. Menlo Park: The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2015.

Alzheimer Society of Canada. Rising tide: the impact of dementia on canadian society. Toronto: Alzheimer Society of Canada; 2010.

Congress of the United States - Congressional Budget Office. Rising demand for long-term services and supports for elderly people. Washington, DC: CBO; 2013.

Hirdes JP, Mitchell L, Maxwell CJ, White N. Beyond the ‘iron lungs of gerontology’: Using evidence to shape the future of nursing homes in Canada. Can J Aging. 2011;30:371–90.

Estabrooks CA, Poss JW, Squires JE, Teare GF, Morgan DG, Stewart N, Doupe MB, Cummings GG, Norton PG. A profile of residents in prairie nursing homes. Can J Aging. 2013;32:223–31.

Hoffmann F, Kaduszkiewicz H, Glaeske G, van den Bussche H, Koller D. Prevalence of dementia in nursing home and community-dwelling older adults in Germany. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2014;26:555–9.

Stewart R, Hotopf M, Dewey M, Ballard C, Bisla J, Calem M, Fahmy V, Hockley J, Kinley J, Pearce H, et al. Current prevalence of dementia, depression and behavioural problems in the older adult care home sector: the South East London Care Home Survey. Age Ageing. 2014;43:562–7.

Bartfay E, Bartfay WJ, Gorey KM. Prevalence and correlates of potentially undetected dementia among residents of institutional care facilities in Ontario, Canada, 2009-2011. Int J Geriatric Psychiatry. 2013;28:1086–94.

Alzheimer’s Association. Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Chicago: Alzheimer’s Association; 2014.

World Health Organization. World Health Statistics 2014. Geneva, Switzerland; 2014.

Alzheimer’s Disease International. World Alzheimer Report 2015: The global impact of dementia - an analysis of prevalence, incidence, cost and trends. London: ADI; 2015.

Health Council of Canada. Seniors in need, caregivers in distress: What are the home care priorities for seniors in Canada? Toronto: Health Council of Canada; 2012.

Canadian Healthcare Association. New directions for facility-based long term care. In: Series: Policy brief (CHA Press). Ottawa: CHA; 2007.

Jansen I, Murphy J. Residential long-term care in Canada: our vision for better seniors’ care. St. Laurent. Ottawa: Canadian Union of Public Employees; 2009.

McGregor MJ, Ronald LA. Residential Long-Term Care for Canadian Seniors: Nonprofit, For-Profit or Does It Matter? Montreal: Institute for Research on Public Policy (IRPP); 2011.

Berta W, Laporte A, Deber R, Baumann A, Gamble B. The evolving role of health care aides in the long-term care and home and community care sectors in Canada. Hum Resour Health. 2013;11:25.

Castle NG, Ferguson JC. What is nursing home quality and how is it measured? The Gerontol. 2010;50:426–42.

Rantz MJ, Zwygart-Stauffacher M, Flesner M, Hicks L, Mehr D, Russell T, Minner D. Challenges of using quality improvement methods in nursing homes that “need improvement”. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13:732–8.

Temkin-Greener HP, Zheng N, Katz PMD, Zhao HS, Mukamel DBP. Measuring work environment and performance in nursing homes. Med Care. 2009;47:482–91.

Tolson D, Rolland Y, Andrieu S, Aquino J-P, Beard J, Benetos A, Berrut G, Coll-Planas L, Dong B, Forette F, et al. International Association of Gerontology and Geriatrics: A Global agenda for clinical research and quality of care in nursing homes. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2011;12:184–9.

Rantz MJ, Zwygart-Stauffacher M, Hicks L, Mehr D, Flesner M, Petroski GF, Madsen RW, Scott-Cawiezell J. Randomized multilevel intervention to improve outcomes of residents in nursing homes in need of improvement. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13:60–8.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD): OECD health statistics 2015: Long-term care resources and utilisation -- long-term care recipients. http://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?queryid=30143## (2015). Accessed 28 June 2016.

National Advisory Council on Aging. Press Release. NACA demands improvement to Canada’s long term care institutions. Ottawa: National Advisory Council on Aging; 2005.

Dunn F. Report of the Auditor General on Seniors Care and Programs. Edmonton: Auditor General; 2005

British Columbia Office of the Ombudsperson. The Best of Care: Getting It Right for Seniors in British Columbia. Vancouver: Office of the Ombudsperson, British Columbia; 2010.

Long-Term Care Task Force Ontario. Long-Term Care Task Force on Residential Care and Safety: An Action Plan to Address Abuse and Neglect in Long-Term Care Homes. Ottawa: Long-Term Care Task Force Ontario; 2012.

Doupe M, Brownell M, Kozyrskyj A, Dik N, Burchill C, Dahl M, Chateau D, DeCoster C, Hing E, Bodnarchuk J. Using Administrative Data to Develop Indicators of Quality Care in Personal Care Homes. Winnipeg: Manitoba Centre for Health Policy, Department of Community Health Sciences, University of Manitoba; 2006

Baumgarten M, Margolis D, Gruber-Baldini AL, Zimmerman S, German P, Hebel JR, Magaziner J. Pressure ulcers and the transition to long-term care. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2003;16:299–304.

Friedman SM, Williamson JD, Lee BH, Ankrom MA, Ryan SD, Denman SJ. Increased fall rates in nursing home residents after relocation to a new facility. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995;43:1237–42.

Mitchell SL, Kiely DK, Hamel MB, Park PS, Morris JN, Fries BE. Estimating prognosis for nursing home residents with advanced dementia. JAMA. 2004;291:2734–40.

Rapp K, Lamb SE, Buchele G, Lall R, Lindemann U, Becker C. Prevention of falls in nursing homes: Subgroup analyses of a randomized fall prevention trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1092–7.

McGregor MJ, Tate RB, McGrail KM, Ronald LA, Broemeling AM, Cohen M. Care outcomes in long-term care facilities in British Columbia, Canada. Does ownership matter? Med Care. 2006;44:929–35.

Boström A-M, Kajermo KN, Nordström G, Wallin L. Registered nurses’ use of research fndings in the care of older people. J Clin Nurs. 2008;17:1430–41.

Estabrooks CA, Derksen L, Winther C, Lavis JN, Scott SD, Wallin L, Profetto-McGrath J. The intellectual structure and substance of the knowledge utilization field: a longitudinal author co-citation analysis, 1945 to 2004. Implement Sci. 2008;3:49.

Grimshaw JM, Eccles MP, Lavis JN, Hill SJ, Squires JE. Knowledge translation of research findings. Implement Sci. 2012;7:50.

Grol R, Grimshaw JM. From best evidence to best practice: Effective implementation of change in patients’ care. Lancet. 2003;362:1225–30.

Schuster M, McGlynn E, Brook R. How good is the quality of health care in the United States? Milbank Q. 1998;76:517–63.

Schuster MA, McGlynn EA, Brook RH. How good is the quality of health care in the United States? Milbank Q. 2005;83:843–95.

Masso M, McCarthy G. Literature review to identify factors that support implementation of evidence-based practice in residential aged care. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2009;7:145–56.

Rahman AN, Applebaum RA, Schnelle JF, Simmons SF. Translating research into practice in nursing homes: Can we close the gap? The Gerontologist. 2012;52:597–606.

Morley JE, Caplan G, Cesari M, Dong B, Flaherty JH, Grossberg GT, Holmerova I, Katz PR, Koopmans R, Little MO, et al. International survey of nursing home research priorities. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15:309–12.

Boström A-M, Slaughter SE, Chojecki D, Estabrooks CA. What do we know about knowledge translation in the care of older adults? A scoping review. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13:210–9.

Morley JE. Certified nursing assistants: a key to resident quality of life. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15:610–2.

Estabrooks CA, Hutchinson AM, Squires JE, Birdsell J, Cummings GG, Degner L, Morgan D, Norton PG. Translating Research in Elder Care: An introduction to a study protocol series. Implement Sci. 2009;4:51.

Estabrooks CA, Squires JE, Cummings GG, Teare GF, Norton PG. Study protocol for the Translating Research in Elder Care (TREC): Building context – an organizational monitoring program in long-term care project (project one). Implement Sci. 2009;4:52.

Estabrooks CA, Morgan DG, Squires JE, Bostrom AM, Slaughter SE, Cummings GG, Norton PG. The care unit in nursing home research: evidence in support of a definition. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11:46.

Norton PG, Murray M, Doupe MB, Cummings GG, Poss JW, Squires JE, Teare GF, Estabrooks CA. Facility versus unit level reporting of quality indicators in nursing homes when performance monitoring is the goal. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e004488.

Anderson RA, Issel LM, McDaniel RR. Nursing homes as complex adaptive systems: Relationship between management practice and resident outcomes. Nurs Res. 2003;52:12–21.

Rincon TA. Integration of evidence-based knowledge management in microsystems: a tele-ICU experience. Crit Care Nurs Q. 2012;35:335–40.

Likosky DS. Clinical microsystems: a critical framework for crossing the quality chasm. J Extra-Corporeal Technol. 2014;46:33–7.

Nelson EC, Batalden PB, Godfrey MM. Quality by design: a clinical microsystems approach. Somerset: Wiley; 2007.

Nelson EC, Batalden PB, Huber TP, Mohr JJ, Godfrey MM, Headrick LA, Wasson JH. Microsystems in health care: Part 1. Learning from high-performing front-line clinical units. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 2002;28:472–93.

Lanham HJ. A complexity science perspective of organizational behavior in clinical microsystems. In: Sturmberg JP, Martin CM, editors. Handbook of systems and complexity in health. Secaucus: Springer; 2013. p. 715–25.

Estabrooks CA, Scott S, Squires JE, Stevens B, O’Brien-Pallas L, Watt-Watson J, Profetto-Mcgrath J, McGilton K, Golden-Biddle K, Lander J, et al. Patterns of research utilization on patient care units. Implement Sci. 2008;3:31.

Nelson EC, Godfrey MM, Batalden PB, Berry SA, Bothe AE, McKinley KE, Melin CN, Muething SE, Moore LG, Wasson JH, et al. Clinical microsystems, Part 1. The building blocks of health systems. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34:367–78.

Williams I, Dickinson H, Robinson S, Allen C. Clinical microsystems and the NHS: a sustainable method for improvement? J Health Organ Manag. 2009;23:119–32.

Kjøs B, Botten G, Gjevjon E, Romøren T. Quality work in long-term care: the role of first-line leaders. International J Qual Health Care. 2010;22:351–7.

Morris JN, Moore T, Jones R, Mor V, Angelelli J, Berg K, Hale C, Morris S, Murphy K, Rennison M. Validation of long-term and post-acute care quality indicators. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Abt Associates Inc, Brown University; 2003.

Anderson RA, Corazzini K, Porter K, Daily K, McDaniel Jr RR, Colon-Emeric C. CONNECT for quality: protocol of a cluster randomized controlled trial to improve fall prevention in nursing homes. Implement Sci. 2012;7:11.

Colon-Emeric CS, McConnell E, Pinheiro SO, Corazzini K, Porter K, Earp KM, Landerman L, Beales J, Lipscomb J, Hancock K, et al. CONNECT for better fall prevention in nursing homes: results from a pilot intervention study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61:2150–9.

Lanham HJ, Leykum LK, Taylor BS, McCannon CJ, Lindberg C, Lester RT. How complexity science can inform scale-up and spread in health care: understanding the role of self-organization in variation across local contexts. Soc Sci Med. 2013;93:194–202.

McDaniel RR Jr, Driebe DJ. Complexity science and health care management. In: Advances in health care management, volume 3. Edited by Savage GT, Blair JD, Fottler MD. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing; 2001. p 11-36.

McDaniel Jr RR, Driebe DJ, Lanham HJ. Health care organizations as complex systems: new perspectives on design and management. Advanced Health Care Management. 2013;15:3–26.

Janes N, Sidani S, Cott C, Rappolt S. Figuring it out in the moment: A theory of unregulated care providers’ knowledge utilization in dementia care settings. Worldviews Evid-Based Nurs. 2008;5:13–24.

Hughes CM, Donnelly A, Moyes SA, Peri K, Scahill S, Chen C, McCormack B, Kerse N. “The way we do things around here”: An international comparison of treatment culture in nursing homes. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13:360–7.

Lopez R, Amella EJ, Strumpf NE, Teno JM, Mitchell SL. The influence of nursing home culture on the use of feeding tubes. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:83–8.

Nieboer AP, Strating MMH. Innovative culture in long-term care settings: The influence of organizational characteristics. Health Care Manag Rev. 2012;37:165–74.

Hughes CM, Lapane K, Watson MC, Davies HTO. Does organisational culture influence prescribing in care homes for older people?: A new direction for research. Drugs Aging. 2007;24:81–93.

Bonner AF, Castle NG, Men A, Handler SM. Certified nursing assistants’ perceptions of nursing home patient safety culture: Is there a relationship to clinical outcomes? J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2009;10:11–20.

Svarstad BL, Mount JK, Bigelow W. Variations in the treatment culture of nursing homes and responses to regulations to reduce drug use. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52:666–72.

van Beek APA, Gerritsen DL. The relationship between organizational culture of nursing staff and quality of care for residents with dementia: Questionnaire surveys and systematic observations in nursing homes. Int J Nurs Stud. 2010;47:1274–82.

Harvey G, Loftus-Hills A, Rycroft-Malone J, Titchen A, Kitson A, McCormack B, Seers K. Getting evidence into practice: The role and function of facilitation. J Adv Nurs. 2002;37:577–88.

Welsh S, Edwards M, Hunter L. Caring for smiles--a new educational resource for oral health training in care homes. Gerodontology. 2012;29:e1161–2.

Berta W, Teare GF, Gilbart E, Ginsburg LS, Lemieux-Charles L, Davis D, Rappolt S. Spanning the know-do gap: understanding knowledge application and capacity in long-term care homes. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70:1326–34.

Grol RP, Bosch MC, Hulscher ME, Eccles MP, Wensing M. Planning and studying improvement in patient care: The use of theoretical perspectives. Milbank Q. 2007;85:93–138.

Damschroder L, Aron D, Keith R, Kirsh S, Alexander J, Lowery J. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4:50.

Estabrooks CA, Squires JE, Cummings GG, Birdsell JM, Norton PG. Development and assessment of the Alberta Context Tool. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:234.

French B, Thomas L, Baker P, Burton C, Pennington L, Roddam H. What can management theories offer evidence-based practice? A comparative analysis of measurement tools for organisational context. Implementation Sci. 2009;4:28.

Kaplan HC, Provost LP, Froehle CM, Margolis PA. The Model for Understanding Success in Quality (MUSIQ): building a theory of context in healthcare quality improvement. BMJ Quality & Safety. 2012;21:13–20.

Kitson A, Harvey G, McCormack B. Enabling the implementation of evidence based practice: a conceptual framework. Qual Health Care. 1998;7:149–58.

Kitson AL, Rycroft-Malone J, Harvey G, McCormack B, Seers K, Titchen A. Evaluating the successful implementation of evidence into practice using the PARiHS framework: Theoretical and practical challenges. Implement Sci. 2008;3:1.

McCormack B, McCarthy G, Wright J, Coffey A. Development and testing of the Context Assessment Index (CAI). Worldviews Evid-Based Nurs. 2009;6:27–35.

Barnett J, Vasileiou K, Djemil F, Brooks L, Young T. Understanding innovators’ experiences of barriers and facilitators in implementation and diffusion of healthcare service innovations: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:342.

Cummings GG, Estabrooks CA, Midodzi WK, Wallin L, Hayduk L. Influence of organizational characteristics and context on research utilization. Nurs Res. 2007;56:S24–39.

Estabrooks CA, Midodzi WK, Cummings GG, Wallin L. Predicting research use in nursing organizations: A multilevel analysis. Nurs Res. 2007;56:S7–23.

Janssen MAP, van Achterberg T, Adriaansen MJM, Kampshoff CS, Schalk DMJ, Mintjes-de GJ. Factors influencing the implementation of the guideline Triage in emergency departments: A qualitative study. J Clin Nurs. 2012;21:437–47.

Pepler CJ, Edgar L, Frisch S, Rennick J, Swidzinski M, White C, Brown TG, Gross J. Unit culture and research-based nursing practice in acute care. Can J Nurs Res. 2005;37:66–85.

Scott SD, Estabrooks CA, Allen M, Pollock C. A context of uncertainty: How context shapes nurses’ research utilization behaviors. Qual Health Res. 2008;18:347–57.

Berta W, Teare GF, Gilbart E, Ginsburg LS, Lemieux-Charles L, Davis D, Rappolt S. The contingencies of organizational learning in long-term care: factors that affect innovation adoption. Health Care Manag Rev. 2005;30:282–92.

Estabrooks CA. Translating research into practice: implications for organizations and administrators. Can J Nurs Res. 2003;35:53–68.

Fleuren M, Wiefferink K, Paulussen T. Determinants of innovation within health care organizations. Int J Qual Health Care. 2004;16:107–23.

Glisson C. Assessing and changing organizational culture and climate for effective services. Res Soc Work Pract. 2007;17:736–47.

Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane F, Bate P, Kyriakidou O. Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: Systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Q. 2004;82:581–629.

Kaplan HC, Brady PW, Dritz MC, Hooper DK, Linam WM, Froehle CM, Margolis P. The influence of context on quality improvement success in health care: A systematic review of the literature. Milbank Q. 2010;88:500–59.

Dopson S, Fitzgerald L, editors. Knowledge to Action? Evidence-Based Health Care in Context. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2005.

Contandriopoulos D, Lemire M, Denis JL, Tremblay E. Knowledge exchange processes in organizations and policy arenas: a narrative systematic review of the literature. Milbank Q. 2010;88:444–83.

Hutchinson AM, Mallidou AA, Toth F, Cummings GG, Schalm C, Estabrooks CA: Review and synthesis of literature examining characteristics of organizational context that influence knowledge translation in healthcare: Technical Report. In. (KUSP Report No. 10-01-TR). Edmonton: University of Alberta. (ISBN: 978-1-55195-269-7); 2010

Estabrooks C, Squires J, Hutchinson A, Scott S, Cummings G, Kang S, Midodzi W, Stevens B. Assessment of variation in the alberta context tool: the contribution of unit level contextual factors and specialty in Canadian pediatric acute care settings. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:251.

Estabrooks CA, Squires JE, Cummings GG, Morgan D, Stewart N, Ginsburg L, Hayduk L, McGilton K, Kang SH, Norton P. The influence of organizational context on best practice use by care aides in residential long-term care settings. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. in press.

Squires J, Estabrooks C, Scott S, Cummings G, Hayduk L, Kang S, Stevens B. The influence of organizational context on the use of research by nurses in Canadian pediatric hospitals. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:351.

Estabrooks CA, Squires JE, Hayduk LA, Cummings GG, Norton PG. Advancing the argument for validity of the Alberta Context Tool with healthcare aides in residential long-term care. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11:107.

Cummings GG, Hutchinson AM, Scott S, Norton PG, Estabrooks CA. The relationship between characteristics of context and research utilization in a pediatric setting. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:168.

Estabrooks CA, Hoben M, Poss JW, Chamberlain SA, Thompson GN, Silvius JL, Norton PG. Dying in a nursing home: Treatable symptom burden and its link to modifiable features of work context. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. in press.

Chan AW, Tetzlaff JM, Gotzsche PC, Altman DG, Mann H, Berlin JA, Dickersin K, Hrobjartsson A, Schulz KF, Parulekar WR, et al. SPIRIT 2013 explanation and elaboration: guidance for protocols of clinical trials. BMJ. 2013;346:e7586.

Arnold BF, Hogan DR, Colford Jr JM, Hubbard AE. Simulation methods to estimate design power: an overview for applied research. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11:94.

Guo Y, Logan HL, Glueck DH, Muller KE. Selecting a sample size for studies with repeated measures. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13:100.

Campbell MJ, Walters SJ. How to design, analyse and report cluster randomised trials in medicine and health related research. Chinchester: Wiley; 2014.

CRAN: The Comprehensive R Archive Network. http://cran.r-project.org/ (2014). Accessed February 28, 2015.

Estabrooks CA, Teare G, Norton PG. Should we feed back research results in the midst of a study? Implement Sci. 2012;7:87.

Bostrom A-M, Cranley L, Hutchinson AM, Cummings GG, Norton P, Estabrooks CA. Nursing home administrators’ perspectives on a study feedback report: A cross sectional survey. Implement Sci. 2012;7:88.

Hutchinson AM, Batra-Garga N, Cranley L, Bostrom A-M, Cummings GG, Norton P, Estabrooks CA. Feedback reporting of survey data to healthcare aides. Implement Sci. 2012;7:89.

Translating Research in Elder Care (TREC). Minimum number of care aide responses needed per care unit to obtain stable, valid and reliable unit-aggregated ACT scores. (Internal report, available upon request). Edmonton: TREC; 2010.

Howe A, Keogh-Brown M, Miles S, Bachmann M. Expert consensus on contamination in educational trials elicited by a Delphi exercise. Med Educ. 2007;41:196–204.

Keogh-Brown M, Bachmann M, Shepstone L, Hewitt C, Howe A, Ramsay C, Song F, Miles J, Torgerson D, Miles S, et al. Contamination in trials of educational interventions. Health Technol Assess. 2007;11.

May C, Mair F, Dowrick C, Finch T. Process evaluation for complex interventions in primary care: understanding trials using the normalization process model. BMC Fam Pract. 2007;8:42.

Katz PR, Karuza J, Intrator O, Zinn J, Mor V, Caprio T, Caprio A, Dauenhauer J, Lima J. Medical staff organization in nursing homes: Scale development and validation. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2009;10:498–504.

Canadian Institute for Health Information. Data quality documentation, continuing care reporting system, 2013-2014. Ottawa, ON: CIHI; 2015.

Canadian Institute for Health Information. Continuing care reporting system RAI-MDS 2.0 output specifications, 2014–2015. Ottawa: CIHI; 2015.

Estabrooks CA, Knopp-Sihota JA, Norton PG. Practice sensitive quality indicators in RAI-MDS 2.0 nursing home data. BMC Res Notes. 2013;6:460.

Squires JE, Hutchinson AM, Bostrom AM, Deis K, Norton PG, Cummings GG, Estabrooks CA. A data quality control program for computer-assisted personal interviews. Nurs Res Pract. 2012;2012.

Forjaz MJ, Rodriguez-Blazquez C, Ayala A, Rodriguez-Rodriguez V, de Pedro-Cuesta J, Garcia-Gutierrez S, Prados-Torres A. Chronic conditions, disability, and quality of life in older adults with multimorbidity in Spain. Eur J Intern Med. 2015;26:176–81.

Diaz M, Neuhauser D. Pasteur and parachutes: When statistical process control is better than a randomized controlled trial. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005;14:140–3.

Montgomery DC. Introduction to Statistical Quality Control. 3rd ed. New York: John WIley and Sons; 1996.

Thor J, Lundberg J, Ask J, Olsson J, Carli C, Härenstam KP, Brommels M. Application of statistical process control in healthcare improvement: systematic review. Qual Saf Health Care. 2007;16:387–99.

Timmerman T, Verrall T, Clatney L, Klomp H, Teare G. Taking a closer look: Using statistical process control to identify patterns of improvement in a quality-improvement collaborative. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19:1–6.

Ivers N, Jamtvedt G, Flottorp S, Young JM, Odgaard-Jensen J, French SD, O’Brien MA, Johansen M, Grimshaw J, Oxman AD. Audit and feedback: effects on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;6:CD000259.

Ivers NM, Sales A, Colquhoun H, Michie S, Foy R, Francis JJ, Grimshaw JM. No more ‘business as usual’ with audit and feedback interventions: towards an agenda for a reinvigorated intervention. Implement Sci. 2014;9:14.

Colquhoun H, Brehaut J, Sales A, Ivers N, Grimshaw J, Michie S, Carroll K, Chalifoux M, Eva K. A systematic review of the use of theory in randomized controlled trials of audit and feedback. Implement Sci. 2013;8:66.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Fiona Clement for her support in developing the cost assessment component of this study. We would also like to thank Elizabeth Anderson, Anne-Marie Boström, Lisa Cranley, James Dearing, Jayna Holroyd-Leduc, Johan Thor, and Lori Weeks for their active participation in the INFORM committee meetings, and for their valuable contribution to developing and reviewing workshop contents and documents, as well as, process evaluation materials and processes.

Funding

INFORM is funded by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Transitional Operational Grant (Application Number: 341532). The funder has not played and will not play any role in study design; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing of the report; and the decision to submit the report for publication, and they have not had and will not have ultimate authority over any of these activities.

Availability of data and materials

TREC has established comprehensive data and intellectual property policies, formalizing in detail the accountability for the management of data resources (including definition, production, access and usage of data), roles and responsibilities of TREC team members, procedures to obtain permission to produce outputs based on TREC data, and procedures to request TREC data in order to generate these outputs. These policies are available upon request. TREC data are housed in the secure and confidential Health Research Data Repository (HRDR) in the Faculty of Nursing at the University of Alberta (https://www.ualberta.ca/nursing/research/supports-and-services/hrdr), in accordance with the health privacy legislation of participating TREC jurisdictions. These health privacy legislations as well as the ethics approval covering TREC data does not allow the removal of completely disaggregated Resident Assessment Instrument – Minimum Data Set (RAI-MDS) 2.0 data (i.e., resident-level records) from the HRDR – even if de-identified. Aggregated RAI-MDS 2.0 summary data and de-identified TREC survey data specific to this study can be requested through the TREC Data Management Committee (joseph.akinlawon@ualberta.ca) on the condition that researchers meet and comply with the TREC and HRDR data confidentiality policies.

Authors’ contributions

MH, PGN, LRG, RAA, GGC, HJL, JES, DT, ASW, and CAE are investigators or knowledge users on the INFORM grant, have substantially contributed to developing the research proposal, and are actively involved in launching and carrying out the study. CE is the PI of TREC and INFORM. MH carried out the sample size simulations, prepared the first draft of this manuscript including all figures and tables, coordinated the review process within the authorship team, and incorporated revisions. MH, LRG, PGN, and CAE lead the development of the intervention, RAA, GGC, HJL, JES, DT, and ASW actively contributed to the intervention development. LRG in collaboration with MH lead the development of the process evaluation. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript in several rounds, suggested revisions and read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare to have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Boards of the University of Alberta (Pro00059741), Covenant Health (1758), University of British Columbia (H15-03344), Fraser Health Authority (2016-026), and Interior Health Authority (2015-16-082-H). Operational approval will be obtained from all included facilities if required. Written informed consent will be completed with facilities and study participants.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional files

Additional file 1:

INFORM_trial_protocol_add1_SPIRIT_checklist_30Apr2016.pdf, SPIRIT Checklist. (PDF 179 kb)

Additional file 2:

INFORM_trial_protocol_add2_terms_of_reference_30Apr2016.pdf, Terms of reference INFORM committee and working group structure. (PDF 34 kb)

Additional file 3:

INFORM_trial_protocol_add3_info_materials_30Apr2016.pdf, INFORM information sheet and informed consents. (PDF 57 kb)

Additional file 4:

INFORM_trial_protocol_add4_theoretical_framing_30Apr2016.pdf, Theoretical framing of the study intervention. (PDF 180 kb)

Additional file 5:

INFORM_trial_protocol_add5_primary_outcome_select_30Apr2016.pdf, Reasons for choosing Formal Interactions as primary study outcome. (PDF 188 kb)

Additional file 6:

INFORM_trial_protocol_add6_blinding_30Apr2016.pdf, Blinding of INFORM stakeholders. (PDF 148 kb)

Additional file 7:

INFORM_trial_protocol_add7_study_outcomes_30Apr2016.pdf, Primary and secondary study outcomes, and instruments used to assess these outcomes. (PDF 517 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Hoben, M., Norton, P.G., Ginsburg, L.R. et al. Improving Nursing Home Care through Feedback On PerfoRMance Data (INFORM): Protocol for a cluster-randomized trial. Trials 18, 9 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-016-1748-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-016-1748-8