Abstract

Purpose

To compare the efficacy of systemic treatment with linezolid (LNZ) versus vancomycin (VAN) on methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) burden and eradication in endotracheal tube (ETT) biofilm and ETT cuff from orotracheally intubated patients with MRSA respiratory infection.

Methods

Prospective observational clinical study was carried out at four European tertiary hospitals. Plasma and endotracheal aspirate (ETA) levels of LNZ and VAN were determined 72 h after treatment initiation through high-performance liquid chromatography or bioassay. LNZ or VAN concentration in the ETT biofilm and MRSA burden and eradication was determined upon extubation. The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) for LNZ and VAN was assessed by E-test strips (Biomerieux®). Scanning electron microscopy images were obtained, and ETT biofilm thickness was compared between groups.

Results

Twenty-five patients, 15 treated with LNZ and 10 with VAN, were included in the study. LNZ presented a significantly higher concentration (μg/mL) than VAN in ETT biofilm (72.8 [1.3–127.1] vs 0.4 [0.4–1.3], p < 0.001), although both drugs achieved therapeutic plasma levels 72 h after treatment initiation. Systemic treatment with LNZ achieved lower ETT cuff MRSA burdens than systemic treatment with VAN. Indeed, LNZ increased the MRSA eradication rate in ETT cuff compared with VAN (LNZ 75%, VAN 20%, p = 0.031).

Conclusions

In ICU patients with MRSA respiratory infection intubated for long periods, systemic treatment with LNZ obtains a greater beneficial effect than VAN in limiting MRSA burden in ETT cuff.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In orotracheally intubated critically ill patients, bacteria from the oropharyngeal or gastric microbiota can rapidly colonize the lower respiratory airways passing over the endotracheal tube cuff (ETT cuff) and colonizing the inner ETT surface by forming biofilms [1, 2]. Thus, these patients are especially vulnerable to developing a respiratory infection caused by a nosocomial pathogen such as Staphylococcus aureus, in either its methicillin-sensitive (MSSA) or methicillin-resistant (MRSA) form.

S. aureus has recently been identified as the second most frequently isolated microorganism responsible for intensive care unit (ICU)-acquired pneumonia, of which 29% of cases are MRSA [3]. The current clinical guidelines for hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) and ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) published by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Thoracic Society (IDSA/ATS) recommend either intravenous vancomycin (VAN) or linezolid (LNZ) as first-line treatment for MRSA ICU-acquired respiratory infection [4], while the International ERS/ESICM/ESCMID/ALAT guidelines prefer LNZ than VAN [5]. However, the microbiological confirmation of MRSA cultures takes at least 48–72 h, a sufficient time-lapse for ETT biofilm formation.

ETT biofilm formation is currently considered one of the multiple factors that can lead to VAP or its relapse [2]. While several preventive strategies have targeted ETT biofilm eradication [6,7,8,9], none of them has achieved 100% success. The silver-coated ETT and mucus shaver have demonstrated improvements in reducing ETT biofilm in randomized clinical trials but still present certain limitations which may delay their implementation in clinical practice [7, 8]. Although biofilms exhibit antimicrobial tolerance [10], little is known about how antimicrobials affect biofilm formation during endotracheal intubation. In a previous study in pigs with MRSA pneumonia, we found that those treated with LNZ achieved better pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic indices in serum and lung tissue [11], very high levels of LNZ within ETT biofilm, and a lower ETT biofilm MRSA burden in comparison with untreated controls; however, similar rates were not found in the VAN group [12, 13]. What is more, in a study in piglets, Luna et al. found that LNZ was associated with a lower pathology score, better survival, and a trend towards better clearance of MRSA in comparison with glycopeptides [14]. Since it is well known that findings in pigs are not always reproducible in humans [15], we designed a clinical observational study in ICU patients to assess this issue.

Our study aimed to determine the effect of systemic treatment with LNZ vs VAN on ETT biofilm from ICU patients with respiratory MRSA infection, including LNZ and VAN concentration measurements within plasma and endotracheal aspirate (ETA) 72 h after treatment initiation and within ETT biofilm upon extubation.

Materials and methods

Patients

The study was conducted at the medical and surgical ICUs of four university hospitals in southern Europe, three in Spain and one in Italy. The following hospitals enrolled patients: Hospital Clinic, Barcelona, Spain (including the following ICUs: Respiratory, Medical, Surgical, Cardiovascular and Hepatic), Hospital del Mar (Critical Care Dept), also in Barcelona, Spain, Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias, in Oviedo, Spain (Intensive Medicine Service), and the Fondazione IRCCS Ca’ Granda, Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, in Milan, Italy (Adult Intensive Care).

Data were prospectively collected from September 2013 to December 2016. The investigators made daily rounds in all ICUs. Patients were included consecutively, and only the first episode was analyzed. All patients were over 18 and had respiratory infection due to S. aureus (confirmed microbiologically) with ≥ 48 h of orotracheal intubation and ≥ 48 h of treatment with either LNZ or VAN. Patients with severe immunosuppression (neutropenia after chemotherapy or hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, drug-induced immunosuppression in solid–organ transplant or cytotoxic therapy, and HIV infection-related disorders) were not registered.

The study was carried out in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki (current version, Fortaleza, Brazil, October 2013) and was conducted in accordance with the requirements of the 2007 Spanish Biomedical Research Act. The study was approved by the institution’s Internal Review Board (registry number 2012/7927). Written informed consent was obtained from patients or their next of kin.

Definitions

The clinical suspicion of pneumonia was based on clinical criteria. We considered VAP in patients with previous invasive mechanical ventilation for 48 h or more. Patients were classified as VAP or non-ventilator ICU-acquired pneumonia (i.e., cases that do not meet the VAP criteria) [16]. Early-onset VAP was defined as occurring within the first 4 days of invasive mechanical ventilation. The respiratory infection was considered ventilator-associated tracheobronchitis when at least two of the aforementioned criteria for pneumonia were found in the absence of radiographic signs of new pneumonia [17]. Severe community-acquired pneumonia (SCAP) was defined according to the 2007 IDSA/ATS guidelines [18] and as previously defined [19]. All SCAP patients included required invasive mechanical ventilation.

Microbiology and antimicrobial treatment

The microbiological evaluation has been extensively addressed in previous reports [20]. Microbial identification and susceptibility testing were performed by standard methods [21, 22].

The initial empiric antimicrobial treatment was administered according to local adaptations of international guidelines [5] and subsequently revised according to the microbiology results.

Data collection and severity assessment

All relevant data were collected at admission and at the onset of pneumonia from the medical records and bedside flow charts, including clinical, laboratory, radiological, and microbiological information. Patients were followed until the end of mechanical ventilation.

The severity assessment included the APACHE-II [23] and the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) [24] score on ICU admission at microbial diagnosis and at orotracheal extubation.

Endotracheal tube preparation and microbiology analysis

All ETTs from the patients included were collected and stored at − 80 °C until analysis. All ETTs were number coded so that the investigators would be blind to treatment group allocation during the analysis. For the first time, we also included the microbiological culture of the ETT cuff. The ETT cuff was dissected and microbiologically processed before rinsing the outer surface and slicing the ETT, following our methodology published elsewhere [12]. Both ETT cuff and ETT were sonicated before microbiological cultures. Bacterial growth was quantified and reported as logarithmic scale of colony-forming units per milliliter (log10 CFU/mL). Susceptibility to oxacillin, linezolid, and vancomycin was assessed for all S. aureus strains isolated from ETT through E-test strips (Biomerieux, France) using ATCC25923 strain as standard laboratory testing control strain, following the manufacturer’s recommendations.

Determination of MLST from Sanger data and phylogenetic analyses

The Sanger sequences were used to obtain the allelic profile of seven S. aureus housekeeping genes (arcC, aroE, glpF, gmk, pta, tpi, yqiL). The genes were concatenated by the MLST.net database. The MLST results were compared to references in NCBI and the S. aureus MLST database in order to assign sequence type (ST). The MLST results were compared against the MLST database (https://pubmlst.org/saureus/) using comparative eBURST V3 software employing the BURST algorithm [25]. Accessory gene regulator (agr) type I, II, III, IV, or V was confirmed by conventional polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using previously described primers and reaction conditions [26].

Antibiotic concentration in biological matrixes

LNZ or VAN concentrations in biological matrixes (i.e., plasma, ETA, and ETT biofilm) were determined using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) as previously described [11]. To release antibiotics from ETA and biofilm and to perform the HPLC, we applied our methodology previously described elsewhere [12]. The lower limit of detection of HPLC was 2.5 μg mL− 1 for both antibiotics. When the sample was below detection limit (BDL), the value assigned was 1.25 μg/mL.

A bioassay was alternatively performed for the detection of vancomycin, as previously reported [12]. Bacillus subtillis (ATCC 6633) in Mueller-Hinton Agar was used for the analysis. The lower limit of detection of the vancomycin bioassay was 0.70 μg mL− 1. When the sample was BDL, the value assigned was 0.35 μg/mL.

Scanning electron microscopy

Biofilm was imaged and thickness measured via scanning electron microscopy (SEM) [12]. Briefly, a 1-cm-long hemisection of the ETT distal dependent parts were fixed, dehydrated in graded alcohol series, dried using a polaron critical point drying apparatus, and mounted on commercial SEM stubs (Ted Pella, Inc. Spain). To avoid charge artifacts, the section was sputter-coated with a gold thin layer (sc 510, Fisons Instrument, East Sussex, UK) and carefully silver painted. Samples were imaged via a scanning electron microscope (JEOL JSM 7001F FEG, Japan), and micrographs were recorded on a personal computer. We measured minimal, maximal, and mean biofilm thickness using dedicated software (ImageJ, Wayne Rasband, NIH, USA).

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were reported as number (%), while continuous variables were reported as mean SD or median (interquartile range, IQR), if the distribution was normal or non-normal respectively. Continuous variables between groups were compared using the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or the Kruskal-Wallis test as appropriate. Post hoc pairwise comparisons were carried out via Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) test. Paired samples were compared with the paired t-test or non-parametric Wilcoxon signed-rank test when appropriate. Spearman’s correlation analyses were performed to determine associations between continuous variables. A two-sided p value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data were processed with IBM SPSS Statistic for Windows, version 22.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Subjects

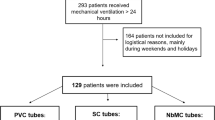

From October 2013 to December 2016, 34 orotracheally intubated patients with microbiologically confirmed S. aureus respiratory infection were consecutively screened for this study, with 20 receiving LNZ and 14 VAN for more than 48 h. Twenty-five of them (15 in the LNZ group and 10 in the VAN group) had MRSA respiratory infection and were included in the analysis (Fig. 1). No significant differences were found between groups in terms of baseline clinical characteristics on ICU admission (Table 1). Nor were any differences found at microbial diagnosis with regard to type of respiratory infection (predominantly ventilator-associated pneumonia, VAP), type of sample (predominantly BAS), MRSA load, radiological diagnosis (predominantly bilateral pneumonia), or severity according to APACHE II and SOFA scores (Table 2).

Quantitative microbiology assessment of ETT and ETT cuff

We collected all 26 ETT from the patients included. For one reintubated patient, we collected the second tube. When this patient was reintubated, the BAS MRSA count was 5 log10 CFU/mL, within the interquartile range of the overall MRSA count at microbial diagnosis in the LNZ arm. There were fewer MRSA-positive ETT cuff cultures in the LNZ than in the VAN group: 4/16 (25%) vs 8/10 (80%, p = 0.031) respectively. Similar results were found within ETT, with positive MRSA samples in 8/16 (50%) vs 7/10 (70%), p = 0.511 in the LNZ and VAN groups respectively, though the differences were not statistically significant. The MRSA load (log10 CFU/mL) of the LNZ group in the ETT cuff was also significantly lower than in the VAN group. However, the MRSA load within the ETT was not significantly lower in the LNZ group (Fig. 2).

ETT (a) and ETT cuff (b) MRSA load (log10 CFU/mL) in the vancomycin (VAN) and linezolid (LNZ) groups. Each dot represents the MRSA load of each ETT and ETT cuff included into the treatment groups. Black central lines depict median value, while upper and lower gray lines display the 25th and 75th percentiles. Median [IQR] ETT MRSA load was not inferior in the LNZ group (0.74 [0–4.26] vs 2.25 [0–3.21] log10 CFU/mL, p = 0.83), whereas ETT cuff load was significantly lower in the LNZ-treated patients compared with the VAN treatment group (0 [0–0.75] vs. 3.50 [0.52–5.48] log10 CFU/mL, p = 0.008). ETT, endotracheal tube; MRSA, methicillin-resistant S. aureus; CFU, colony-forming units

No differences were found between LNZ and VAN groups in terms of the presence and load of Gram-positive agents other than S. aureus or in Gram-negative bacteria including Enterobacteriaceae, either in ETT or in ETT cuff. The LNZ group showed a higher presence and load of fungi in ETT cuff than the VAN group, although the difference was not statistically significant: 6 (38%) vs 0 (0%) p = 0.053 and 1.15 ± 1.71 vs 0.00 ± 0.00 log10 CFU/mL, p = 0.028, respectively (Additional file 1: Figure S1). LNZ or VAN treatment during intubation did not differ between groups (Additional file 1: Figure S2).

Emergence of resistance with LNZ and VAN

All S. aureus were susceptible to LNZ or VAN in the microbial diagnosis. Susceptibility to LNZ and VAN remained stable in the S. aureus strains recruited from the ETT and the ETT cuff.

LNZ and VAN concentrations in biological matrixes

At 72 h after treatment initiation, plasma concentrations of LNZ and VAN were 9.00 [6.51–13.46] vs 22.04 [11.18–26.54] μg/mL, p = 0.024 respectively, both figures being above the recommended therapeutic levels (3 μg/mL for LNZ and 15–20 μg/mL for VAN). However, in ETA LNZ was highly concentrated, reaching 38.90 μg/mL [10.22–81.70], while VAN was barely found, at only 2.96 μg/mL [1.86–4.21] (p = 0.145) (Fig. 3).

Linezolid (LNZ) (a) and vancomycin (VAN) (b) concentration in plasma, ETA, and ETT biofilm. In plasma at ETA, LNZ and VAN levels are at 72 h after treatment initiation, in ETT biofilm at extubation. Each dot represents drug concentration of each sample included into the treatment groups. Black central lines depict median value. LNZ median MIC (IQR) was 1.50 [0.88–3.00] μg/mL, while VAN median MIC was 0.75 [0.5–1] μg/mL. The median LNZ and VAN MIC values of the MRSA isolates are indicated by the horizontal gray dashed line while the gray bands represent the 25th–75th percentile ranges in each graph. Of note, LNZ presented high concentrations in ETA and ETT biofilm while VAN concentration fell drastically in ETA and ETT biofilm, to non-therapeutic concentrations. a Plasma vs ETA, p = 0.039; plasma vs ETT biofilm, p = 0.050. b Plasma vs ETA, p = 0.021; plasma vs ETT biofilm, p < 0.001. ETT, endotracheal tube; ETA, endotracheal aspirates; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration

In the LNZ group, seven samples were excluded, three due to absence of biofilm and four due to technical interferences. In the remaining 14 ETT biofilm samples, four were BDL. In general, the overall LNZ concentration within ETT reached high values (72.81 [1.25–127.05] μg/mL), far higher than the median MIC of ETT S. aureus (1.50 [1.00–3.00] μg/mL). Nevertheless, VAN was hardly ever found within ETT (0.35 [0.35–1.31] μg/mL, p < 0.001), or was found at levels very close to the MIC (0.75 [0.50–1.00] μg/mL) (Fig. 3). Specifically, of 14 VAN-treated ETT biofilm samples, nine were BDL. Moreover, within ETT biofilm, LNZ was found 27.64 [1.25–43.69] median folds above each respective S. aureus LNZ MIC, while VAN was found only 0.70 [0.47–2.00] folds above the VAN MIC, p = 0.013.

Clinical outcomes

Ventilatory parameters and gasometry were evaluated at 72 h in both groups (Additional file 1: Table S1). No significant differences between groups were found in length of mechanical intubation or ventilation between LNZ and VAN 9.00[7.00–12.50] and 14.00[8.25–18.75], p = 0.169, or 17.50[9.00–29.25] and 25.00[16.25–40.00], p = 0.170, respectively (Additional file 1: Table S2).

Biofilm through SEM

Scanning electron microscopy images of ETT biofilm from LNZ and VAN groups are shown in Fig. 4. Overall, within the 15 MRSA-positive ETTs, minimal, maximum, and mean thickness did not differ between LNZ and VAN groups.

Scanning electron microscopy images of the highest MRSA load ETT biofilm (106 log10 CFU/mL) in both groups: vancomycin (VAN) (a, b) and linezolid (LNZ) (c, d). Mature biofilms are visible in both groups at low and high magnification. ETT, endotracheal tube; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

MLST and agr

Different types of ST and agr were identified. The ST22 (33%), ST217 (10%), and ST8 (10%) and agr I (81%), agr III (14%), and agr II (5%) were the most frequent types of MRSA isolated. Each of the other ST (1221, 954, 1535, 83, 403, 3060, 45, 87, 121) was found once (5%).

Discussion

Systemic treatment of MRSA respiratory infection with LNZ in mechanically ventilated ICU patients resulted in lower ETT biofilm and ETT cuff MRSA burdens than in patients who received VAN. Indeed, MRSA eradication was superior in ETT (50 vs 30%) and ETT cuff (75 vs 20%) in the LNZ than in the VAN group, although the difference was statistically significant only with regard to ETT cuff. Accordingly, the concentration of LNZ was higher than VAN in ETA and also in ETT biofilm, even though both drugs achieved therapeutic plasma levels at 72 h after treatment initiation.

This is the first report in the literature comparing the effects of LNZ and VAN in ETT from mechanically ventilated humans. Our findings indicate that LNZ is more effective in ETT cuff than VAN, since MRSA presence and loads were significantly lower in the LNZ group. Why is this important?

On the one hand, ETT cuff microfolds, formed in contact with the tracheal wall, are considered a common route of microbial access to the lower respiratory airways [27]. For this reason, attempts have been made in order to minimize ETT cuff aspiration of subglottic secretions. Although these systems lose efficacy over time [28,29,30,31,32], their efficacy can be complemented by systemic antibiotics with ETT biofilm and cuff effect like LNZ, but not VAN.

On the other hand, we demonstrated the superiority of LNZ over VAN in ETA and ETT biofilm drug concentration. The efficacy of LNZ penetrating into respiratory secretions is emphasized by the therapeutic levels achieved by both drugs in plasma compared with their concentrations in ETA 72 h after the first drug administration, in which LNZ remained several folds above the MIC but VAN levels remained subtherapeutic in most of the samples. Notably, the concentrations of LNZ and VAN in ETA (72 h) are indicative of their concentration in ETT biofilm after extubation. Nevertheless, the usefulness of ETA (72 h) for predicting other drug concentrations in ETT biofilm after extubation needs to be investigated further.

Although biofilms exhibit intrinsic tolerance to antibiotics [10, 33], in the ETT, the presence of antibiotics and the development of the biofilm are concomitant. This increases the ability of systemic LNZ treatment to limit biofilm development, as its ETT MRSA eradication rate is 67% higher than that of VAN. However, in critically ill patients, the distribution of LNZ within the ETT, mainly driven by respiratory secretions, is not homogeneous; therefore, its efficacy for eradicating MRSA is not always guaranteed.

All the ETT MRSA were susceptible to LNZ and VAN MIC after long periods of intubation. This clearly highlights that the emergence of resistant strains associated with biofilms is less likely in intubated patients, a finding that is at odds with previous findings in other respiratory diseases [34]. All VAN MIC but two were below 1.5 μg/mL, a threshold MIC that has been previously associated with lower clinical response, higher relapse [35], and increased mortality.

In contrast, we did not find differences in biofilm thickness between LNZ and VAN groups. This may be due to differences between secretion production and microbiota in pigs and in human patients. Thus, the proposal that thickness might be a good indicator of treatment efficacy in a highly controlled experiment [12, 13] may not apply to human patients, where the underlying conditions and other concomitant issues may influence the biofilm and secretions accumulated within the ETT, in addition to length of stay and treatment efficacy.

The results of our study corroborate those of many previous randomized clinical trials. The Zephyr study [36] observed higher rates of clinical cure in nosocomial S. aureus pneumonia (both MRSA and MSSA) when comparing LNZ to VAN. Surprisingly, the IDSA/ATS guidelines still place VAN and LNZ at the same level [4], even though there are enough clinical and animal data to change this recommendation in favor of LNZ [5]. Our study is also in line with a previous study published by our group in a pig model of MRSA pneumonia in animals ventilated for 72 h. However, findings in animals require replication in humans.

The strengths of our study are the following: (1) this is the first comparison of linezolid and vancomycin in ETT biofilms obtained from humans on long-term mechanical ventilation and (2) ETT (including cuff) biofilms and bacterial burden are studied in depth.

A few potential limitations of this study deserve further clarification. This was not a randomized study, and so there is no possibility of comparing the outcomes. In addition, the fact that we had to recruit patients from different hospitals increased the heterogeneity of the ST types involved. Nevertheless, we did not find any differences in patients’ characteristics or in the length of orotracheal intubation between VAN and LNZ groups, and so the heterogeneity of the MRSA ST collected emphasizes the validity of our results and provides realistic epidemiologic data. Secondly, the use of VAN is becoming less and less frequent in Europe, and for this reason, the number of ETT within this group of study was lower than in the LNZ group. Ultimately, these patients received concomitant antimicrobials that may have combined effects with vancomycin or linezolid. However, concomitant antimicrobials were homogeneously distributed between the two treatment groups.

The main clinical implication of our results is that LNZ, which acts effectively in ETT biofilms and cuffs, performs much better than VAN in MRSA eradication and may be important in preventing relapses in MRSA VAP pneumonia.

Conclusions

In conclusion, systemic treatment with linezolid exerts a greater beneficial effect than vancomycin, reducing the MRSA burden within ETT cuff in ICU patients with MRSA respiratory infection who are intubated for long periods. This additional benefit of linezolid should be taken into account when choosing the antibiotics to treat MRSA VAP.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Costerton JW, Stewart PS, Greenberg EP. Bacterial biofilms: a common cause of persistent infections. Science. 1999;21:1318–22.

Fernandez-Barat L, Torres A. Biofilms in ventilator-associated pneumonia. Future Microbiol. 2016;11:1599–610.

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Healthcare-associated infections acquired in intensive care units. In: ECDC. Annual epidemiological report for 2016. Stockholm: ECDC; 2018. 2018. Ref Type: Report.

Kalil AC, Metersky ML, Klompas M, Muscedere J, Sweeney DA, Palmer LB, Napolitano LM, O'Grady NP, Bartlett JG, Carratala J, El Solh AA, Ewig S, Fey PD, File TM Jr, Restrepo MI, Roberts JA, Waterer GW, Cruse P, Knight SL, Brozek JL. Management of adults with hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated pneumonia: 2016 Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Thoracic Society. Clin Infect.Dis. 2016;63:e61–e111.

Torres A, Niederman MS, Chastre J, et al. International ERS/ESICM/ESCMID/ALAT guidelines for the management of hospital-acquired pneumonia and ventilator-associated pneumonia. Eur Respir J. 2017;50:1700582. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.00582-2017.

Kolobow T, Li Bassi G, Curto F, Zanella A. The mucus Slurper: a novel tracheal tube that requires no tracheal tube suctioning. A preliminary report. Intensive Care Med. 2006;32:1414–8.

Kollef MH, Afessa B, Anzueto A, Veremakis C, Kerr KM, Margolis BD, Craven DE, Roberts PR, Arroliga AC, Hubmayr RD, Restrepo MI, Auger WR, Schinner R. Silver-coated endotracheal tubes and incidence of ventilator-associated pneumonia: the NASCENT randomized trial. JAMA. 2008;300:805–13.

Berra L, Coppadoro A, Bittner EA, Kolobow T, Laquerriere P, Pohlmann JR, Bramati S, Moss J, Pesenti A. A clinical assessment of the mucus shaver: a device to keep the endotracheal tube free from secretions. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:119–24.

Bardes JM, Gray D, Wilson A. Effect of the endOclear((R)) device on biofilm in endotracheal tubes. Surg Infect (Larchmt.). 2017;18:293–8.

Mah TF, O'Toole GA. Mechanisms of biofilm resistance to antimicrobial agents. Trends Microbiol. 2001;9:34–9.

Martinez-Olondris P, Rigol M, Soy D, Guerrero L, Agusti C, Quera MA, Li BG, Esperatti M, Luque N, Liapikou M, Filella X, Marco F, de la Bellacasa JP, Torres A. Efficacy of linezolid compared to vancomycin in an experimental model of pneumonia induced by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in ventilated pigs. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(1):162–8.

Fernandez-Barat L, Ferrer M, Sierra JM, Soy D, Guerrero L, Vila J, Li BG, Cortadellas N, Martinez-Olondris P, Rigol M, Esperatti M, Luque N, Saucedo LM, Agusti C, Torres A. Linezolid limits burden of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in biofilm of tracheal tubes. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:2385–9.

Fernandez-Barat L, Li BG, Ferrer M, Bosch A, Calvo M, Vila J, Gabarrus A, Martinez-Olondris P, Rigol M, Esperatti M, Luque N, Torres A. Direct analysis of bacterial viability in endotracheal tube biofilm from a pig model of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia following antimicrobial therapy. FEMS ImmunolMedMicrobiol. 2012;65:309–17.

Luna CM, Bruno DA, Garcia-Morato J, Mann KC, Risso PJ, Sagardia J, Absi R, Garcia BM, Marchetti D, Famiglietti A, Baleztena M, Biancolini C. Effect of linezolid compared with glycopeptides in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus severe pneumonia in piglets. Chest. 2009;135:1564–71.

Marshall JC, Deitch E, Moldawer LL, Opal S, Redl H, Van Der PT. Preclinical models of shock and sepsis: what can they tell us? Shock. 2005;24(Suppl 1):1–6.

Esperatti M, Ferrer M, Theessen A, Liapikou A, Valencia M, Saucedo LM, Zavala E, Welte T, Torres A. Nosocomial pneumonia in the intensive care unit acquired during mechanical ventilation or not. AmJRespirCrit Care Med. 2010;182:1533–9.

Nseir S, Ader F, Marquette CH. Nosocomial tracheobronchitis. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2009;22:148–53.

Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A, Bartlett JG, Campbell GD, Dean NC, Dowell SF, File TM Jr, Musher DM, Niederman MS, Torres A, Whitney CG. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(Suppl 2):S27–72.

Ferrer M, Travierso C, Cilloniz C, Gabarrus A, Ranzani OT, Polverino E, Liapikou A, Blasi F, Torres A. Severe community-acquired pneumonia: characteristics and prognostic factors in ventilated and non-ventilated patients. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0191721.

Fernandez-Barat L, Ferrer M, De RF, Gabarrus A, Esperatti M, Terraneo S, Rinaudo M, Li BG, Torres A. Intensive care unit-acquired pneumonia due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa with and without multidrug resistance. J Inf Secur. 2017;74:142–52.

Magiorakos AP, Srinivasan A, Carey RB, Carmeli Y, Falagas ME, Giske CG, Harbarth S, Hindler JF, Kahlmeter G, Olsson-Liljequist B, Paterson DL, Rice LB, Stelling J, Struelens MJ, Vatopoulos A, Weber JT, Monnet DL. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:268–81.

Camoez M, Sierra JM, Dominguez MA, Ferrer-Navarro M, Vila J, Roca I. Automated categorization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clinical isolates into different clonal complexes by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016;22:161.

Le Gall JR, Lemeshow S, Saulnier F. A new simplified acute physiology score (SAPS II) based on a European/North American multicenter study. JAMA. 1993;270:2957–63.

Vincent JL, Moreno R, Takala J, Willatts S, De Mendonca A, Bruining H, Reinhart CK, Suter PM, Thijs LG. The SOFA (Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. On behalf of the Working Group on Sepsis-Related Problems of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med. 1996;22:707–10.

Ruimy R, Maiga A, rmand-Lefevre L, Maiga I, Diallo A, Koumare AK, Ouattara K, Soumare S, Gaillard K, Lucet JC, Andremont A, Feil EJ. The carriage population of Staphylococcus aureus from Mali is composed of a combination of pandemic clones and the divergent Panton-Valentine leukocidin-positive genotype ST152. Feil EJ, et al. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:1518–30. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14973027

Enright MC, Day NP, DAVIES CE, Peacock SJ, Spratt BG. Multilocus sequence typing for characterization of methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible clones of Staphylococcus aureus. J ClinMicrobiol. 2000;38:1008–15.

Pinciroli R, Mietto C, Berra L. Respiratory therapy device modifications to prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2013;26:175–83.

Berra L, De Marchi L, Panigada M, Yu ZX, Baccarelli A, Kolobow T. Evaluation of continuous aspiration of subglottic secretion in an in vivo study. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:2071–8.

Berra L, Kolobow T, Laquerriere P, Pitts B, Bramati S, Pohlmann J, Marelli C, Panzeri M, Brambillasca P, Villa F, Baccarelli A, Bouthors S, Stelfox HT, Bigatello LM, Moss J, Pesenti A. Internally coated endotracheal tubes with silver sulfadiazine in polyurethane to prevent bacterial colonization: a clinical trial. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34:1030–7.

Tokmaji G, Vermeulen H, Muller MC, Kwakman PH, Schultz MJ, Zaat SA. Silver-coated endotracheal tubes for prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia in critically ill patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;8:CD009201.

Cook G, Costerton JW, Darouiche RO. Direct confocal microscopy studies of the bacterial colonization in vitro of a silver-coated heart valve sewing cuff. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2000;13:169–73.

Valencia M, Ferrer M, Farre R, Navajas D, Badia JR, Nicolas JM, Torres A. Automatic control of tracheal tube cuff pressure in ventilated patients in semirecumbent position: a randomized trial. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:1543–9.

Fernandez-Barat L, Ben-Aicha S, Motos A, Vila J, Marco F, Rigol M, Munoz L, Li BG, Ferrer M, Torres A. Assessment of in vivo versus in vitro biofilm formation of clinical methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates from endotracheal tubes. Sci Rep. 2018;8:11906.

Fernandez-Barat L, Ciofu O, Kragh KN, Pressler T, Johansen U, Motos A, Torres A, Hoiby N. Phenotypic shift in Pseudomonas aeruginosa populations from cystic fibrosis lungs after 2-week antipseudomonal treatment. J CystFibros. 2017;16:222–9.

Choi EY, Huh JW, Lim CM, Koh Y, Kim SH, Choi SH, Kim YS, Kim MN, Hong SB. Relationship between the MIC of vancomycin and clinical outcome in patients with MRSA nosocomial pneumonia. Intensive Care Med. 2011;37:639–47.

Wunderink RG, Niederman MS, Kollef MH, Shorr AF, Kunkel MJ, Baruch A, McGee WT, Reisman A, Chastre J. Linezolid in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus nosocomial pneumonia: a randomized, controlled study. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:621–9.

Acknowledgements

A.M. is the recipient of a Long-Term Research Fellowship (LTRF 2017-01-00073) from the European Respiratory Society (ERS) and the Spanish Society of Pulmonology and Thoracic Surgery (SEPAR). G.L.B. is the recipient of a postdoctoral grant from the Strategic Plan for Research and Innovation in Health (PERIS) 2017–2021. AT was awarded with an ICREA Academy Grant (2014-2018). The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of Josep Mª Nicolas, Elizabeth Zavala, Javier Fernandez, Miquel Ferrer, and Irene Rovira for obtaining endotracheal tubes at their respective ICUs, Jordi Vila for his critical review of the manuscript, and the technical staff at Scientific and Technological Centres of the University of Barcelona (CCiTUB) for their technical support.

Take home message

In ICU patients intubated for long periods, linezolid is superior to vancomycin for eradicating ETT cuff MRSA, and for achieving therapeutic drug levels in ETA and ETT biofilm.

Tweet

Linezolid, but not vancomycin, achieves high MRSA eradication rates in ETT cuff from ICU patients intubated for long periods.

Funding

This study was funded by CIBER de enfermedades respiratorias - Ciberes (CB 06/06/0028), Ciberes is an initiative of ISCIII, unrestricted grant from Pfizer (WI173058), EUROPE ASPIRE award 2011, SGR, IDIBAPS, PERIS ICT 2017 to Gianluigi Li Bassi, and ICREA Academy Award to Prof. Antoni Torres.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LFB, AM, and AT participated in the protocol development, study design, study management, statistical analysis, data interpretation, and writing of the manuscript. LFB, AM, DN, LG, and DS participated in the determination of drug levels in biological matrixes. LFB, AM, RLA, and YL participated in the MLST and agr typing including the analysis of gene sequences. RLA performed the phylogenetic analysis. LFB obtained SEM images. All authors participated in data collection and reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

A. Torres has received grants from MedImmune, Cubist, Bayer, Theravance, and Polyphor and personal fees as Advisory Board member from Bayer, Roche, The Medicines CO, and Curetis. He has received personal speaker’s bureau fees from GSK, Pfizer, Astra Zeneca, and Biotest Advisory Board, unconnected to the study submitted here.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

(DOC 401 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Fernández-Barat, L., Motos, A., Panigada, M. et al. Comparative efficacy of linezolid and vancomycin for endotracheal tube MRSA biofilms from ICU patients. Crit Care 23, 251 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-019-2523-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-019-2523-5